The Polis Project, BreakThrough News, 1804 Books, and The People’s Forum came together in October 2025 to examine how incarceration functions as a central instrument of power across three “democracies” — the United States (often styled the “oldest”), India (the “largest”), and Israel (branded the Middle East’s “only”). Through the lens of three books—Manifestations of Thought, The Trinity of Fundamentals, and How Long Can the Moon Be Caged?—the conversation traced how police and prisons are used to criminalise dissent.

The stories of political prisoners aid resistance. Democratic legitimacy is sustained through carceral control: from the targeting of Black political prisoners confronting white supremacy in the United States, to the incarceration of Indian activists and scholars under sweeping security laws, to the mass detention and hostage-taking of Palestinians within Israeli prisons. Incarceration is a policy designed to deter organising.

Shaka Shakur, a political prisoner incarcerated since 2002, joined the conversation by phone from prison. Shakur has been jailed in Indiana on trumped-up charges of attempting to murder a police official. Addressing the Carceral Republics event, he placed political imprisonment within a longer history of colonialism, racial capitalism, and imperial violence, emphasising the role of prisons as sites of both repression and revolutionary education. Shakur stressed the necessity of internationalism: how struggles in Palestine, India, Haiti, and Black communities in the United States are bound by shared structures of domination.

This event forms part of The Polis Project’s ongoing work to document state violence and amplify the voices of political prisoners.

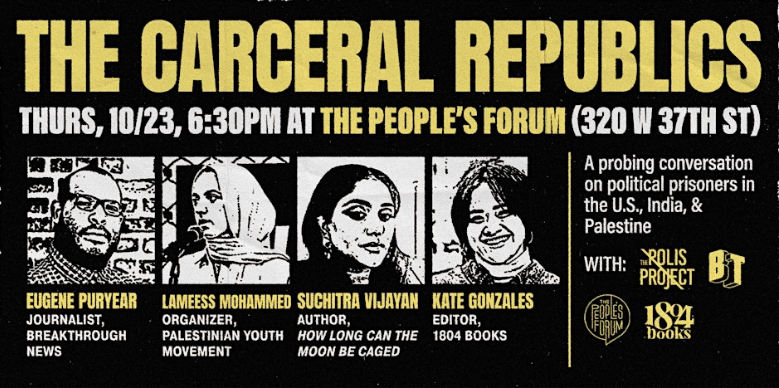

SPEAKERS

Suchitra Vijayan is an essayist, lawyer, and photographer working across oral history, state violence, and visual storytelling. She is the author of How Long Can the Moon Be Caged? Voices of Indian Political Prisoners, and the founder of the Polis Project.

Eugene Puryear is a journalist, writer, activist, politician, and host on The Freedom Side, a weekly show by BreakThrough News.

Lameess Mohammed is an organizer with the Palestinian Youth Movement. PYM focuses on campaigns such as ‘Mask off Maersk’ to demand a global arms embargo, international fundraising initiatives for Gaza, mass mobilizations, and political education projects like the translation of The Trinity of Fundamentals.

The transcript has been edited for length and clarity.

Kate:

Hello, everybody. Thank you so much for choosing to spend your Thursday evening with us, and welcome to The People’s Forum. Is anyone here for the first time by chance?

Well, welcome to the new faces and welcome back to the familiar ones. If you haven’t been here before—or need a refresher—the People’s Forum is a political education centre, a community space, and an art space. We have ongoing courses, volunteer meetings, art builds downstairs, weekly film screenings, and monthly concerts. There are so many ways to engage with revolutionary working-class struggle and to help build a revolutionary culture—one that has been taken from us in the US.

We know that we must study history and working-class movements to strengthen ourselves in the fight for liberation today. That’s why we’re honoured to bring this conversation to The People’s Forum tonight.

We’ll be talking about carceral republics and political prisoners in the US, India, and Israel—or rather, under the occupation of Palestine. In every anti-imperialist movement, there’s always the struggle for the liberation of political prisoners.

As working-class people demand dignity in the face of exploitation and oppression, the ruling class remains determined to preserve the capitalist system that benefits only them. For the ruling class, the system isn’t broken—it works exactly as designed. Maintaining that dominance depends on targeting political leaders and organisers.

The struggle of political prisoners reveals, in a visceral way, how hypocritical and two-faced our ruling class is. In India, Palestine, and the US, governments—or occupational forces—that claim to stand for freedom and democracy instead show us what justice means to them: dehumanisation, violent abuse, and torture behind prison walls, as well as violence outside those walls to silence activists in the first place.

We’ve seen what happened to Palestinian political prisoner Walid Daqqa, unjustly kept in prison, who wrote movingly from his cell and even smuggled sperm across prison walls to continue his family’s lineage. Yet he never lived to see liberation, dying from terminal illness behind bars.

In India, we see the case of the BK-16, as Modi and the BJP stoke the flames of Hindu nationalism. We also remember the assassination of communist leader Govind Pansare in 2015—something we commemorate here every year at The People’s Forum.

And in the US, there’s a long history of political prisoners: Leonard Peltier, Angela Davis, Martin Luther King Jr., and Assata Shakur, who passed away a few weeks ago but died free in revolutionary Cuba.

Today, we’ll be hearing from Shaka Shakur, a New Afrikan political prisoner who will be calling in. He’ll speak about his experiences and about international solidarity across struggles.

As attacks on our leaders and organisers intensify, they expose the threat an organised and united people pose to oppressive systems. The most vibrant movements uphold their political prisoners because these are people who have sacrificed their own freedoms to demand better conditions for all working people.

We’re joined tonight by four thinkers and organisers who have taken on the task of amplifying the voices of political prisoners.

First, Lamees Mohammed, an organiser with the Palestinian Youth Movement. The PYM leads campaigns such as Mask Off Me, which demands a global arms embargo. They run fundraising initiatives for Gaza, mass mobilisations like the Shut It Down for Palestine coalition—which The People’s Forum participates in—and political-education projects like the translation of The Trinity of Fundamentals.

Next, Suchitra Vijayan—essayist, lawyer, and photographer whose work spans oral history, state violence, and visual storytelling. She’s the author of How Long Can the Moon Be Caged? Voices of Indian Political Prisoners, and founder of The Polis Project.

We’re also joined by Eugene Puryear, journalist, writer, activist, politician, and host of The Freedom Side, a weekly show by BreakThrough News. He’s also the author of Shackled and Chained: Mass Incarceration in Capitalist America.

And finally, at 7 p.m., Shaka Shakur will call in from prison. He’s been held captive since 2002 and has remained outspoken for Black liberation. He’s the author of the forthcoming book Manifestations of Thought: When the Dragon Comes, to be released by 1804 Books in the coming weeks, along with a documentary about his life.

Because of the dehumanising bureaucracy of the prison system, Shaka will only have twenty-minute intervals with us, but he’ll keep calling back for the duration of the discussion.

We have a rich, expansive conversation ahead spanning continents and contexts. Please help us make the connections across these struggles. I’ll start with some questions for the panel and then open it up for Q&A.

One last note before we begin: The People’s Forum has recently taken a big step. We bought a building downtown, so we’re no longer at the mercy of landlords who object to a Palestine flag out front. We believe the working class deserves nice things. But we have an ambitious fundraising goal of $2 million to sustain our programming, so we need every contribution you can give.

Now, let’s begin. We’ll start with an audio recording from Shaka to ground the discussion, and then we’ll turn to Lamees.

Shaka:

Greetings, everybody. Power to the people. This is Shaka Shakur, a New Afrikan political prisoner, speaking in international solidarity with the panel.

When we say we stand for human rights, we mean human rights for all—even those who disagree with us ideologically or oppose our politics. To impose oppression on one is to impose it on all.

Our struggle isn’t simply against racism or white supremacy; the primary contradiction is colonialism, neocolonialism, and imperialism—the domination of entire peoples. It’s about the right to self-determination and independence.

It’s striking to see imperialist nations now talking about recognising a Palestinian state after decades of genocide and dispossession supported by the US. These are crimes against international law committed openly and without accountability.

Behind prison walls, our struggle goes beyond freeing ourselves. It’s about educating and organising fellow prisoners, transforming colonial mentalities, and building revolutionary consciousness—turning captives into cadres and soldiers who will return to their communities ready to fight for human rights and liberation.

We recognise the overlapping nature of our struggles—with Palestinians, with Indians, with Haitians resisting domination, with the Congolese fighting the aftershocks of colonial exploitation. All of these struggles trace back to imperial powers profiting from land and resources.

So let’s not be divided by the smoke and mirrors states create to distract us. As we see ICE agents kicking in doors and separating children from parents under the guise of legality, on stolen land, no less. Remember: oppression anywhere is oppression everywhere. Peace.

Kate:

Thank you, Shaka. Lamees. Could you tell us a bit about the Trinity of Fundamentals and the broader context of the Palestinian political struggle?

Lamees:

Thank you, Kate, and thank you, everyone, for being here. It’s an honour to follow that message.

The Trinity of Fundamentals is a novel by Wisam Rafidi. It wouldn’t exist—neither in Arabic nor in English—without collective struggle and solidarity.

Wisam wrote it in 1993 while in prison. It’s a fictionalised account of his years in hiding before his arrest. The story captures a pivotal shift in Palestinian resistance when organisers began going into hiding as the occupation systematically targeted leaders and activists.

Before this change, many would be arrested, spend years in prison, then emerge unable to organise again—denied the ability to work, open bank accounts, or even live normally. Going underground became a way to sustain the struggle.

In the novel, Wisam’s character, Kanan, decides to go into hiding despite his family urging him to surrender. For him, it wasn’t only about evading arrest; it was a strategic contribution to the movement—a tactic of survival and resistance.

The book isn’t romanticised. It captures the loneliness of isolation, the monotony of rereading the same books, and the emotional toll of losing loved ones. Yet throughout, there’s a quiet revolutionary optimism grounded in the reality of occupation.

The novel’s journey from prison to publication is itself a story of collective struggle. Wisam wrote under constant surveillance; comrades warned him when guards approached and hid his pages across cells. Parts were lost, later rewritten from memory, and even smuggled in tiny capsules of plastic, swallowed and retrieved.

Decades later, our team at the Palestinian Youth Movement translated it into English. It took fourteen people, plus a professional translator, working collaboratively—each bringing expertise in Arabic, English, and the history of Palestinian resistance.

So this book is not only about resistance—it is resistance. It embodies the collective determination to preserve stories and voices that the occupation tried to silence.

Kate:

Thank you, Lamees. Shaka has just joined us by phone—can everyone clap so he can hear who’s in the room?

Shaka, can you hear us?

Shaka:

Yes, I can hear you.

Kate:

Excellent. We’ll come back to you shortly, but for now, I’ll turn to Suchitra. Could you tell us a bit about your project and the context in India?

Suchitra:

This moment feels surreal—to be here in conversation while Shaka is literally phoning in from prison.

When the first edition of How Long Can the Moon Be Caged came out, many of the political prisoners we wrote about were still incarcerated. By the second edition, a few had been released, and we included photographs of them walking free. Every single one was smiling—speaking of resistance, of a freer world, always advocating for others.

The book grew out of documentation work by The Polis Project. Around 2020, as India’s right-wing BJP government intensified its repression, we saw a pattern of incarcerating dissent through the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act—a draconian law allowing indefinite detention.

Writers, lawyers, students, and activists were arrested under fabricated charges. We began a series called Profiles of Dissent—not to idolise individuals, but to situate them within their communities: who they were, what shaped them, what laws were used against them, and how long they’d been held.

Each profile ended with prison writings. Nearly every prisoner was writing—poetry, letters, reflections. One man wrote a love poem to his mosquito net because it gave him the only good sleep he had.

Eventually, we compiled these writings into a book. It begins with a timeline tracing, day by day, how repression escalated under Modi’s rule. It then examines the legal architecture of impunity and the material reality of incarceration—objects like the straw denied to Father Stan Swamy, an elderly priest with Parkinson’s who died in custody because the state refused him that basic aid.

The book ends with “Name the Names,” listing every political prisoner we could find—well-known and forgotten alike—because lists matter. They preserve memory against erasure.

Across India, Palestine, and the US, modern states manufacture political prisoners. This book is only a fragment, a beginning of a larger conversation that must continue.

Eugene:

Thanks, Suchitra. I’ll speak a bit about why Manifestations of Thought felt so meaningful to us at 1804 Books, and to me personally.

When Derek first brought me Shaka’s manuscript, I already knew from years of struggling alongside him that it would be powerful. But when I opened it, I realised how essential it was. I told Kate immediately, “We have to do this.” Even with a long publishing list, it felt urgent.

The tradition of the prison text runs deep in Black liberation history. You think of Assata Shakur’s autobiography, George Jackson’s Soledad Brother and Blood in My Eye, Angela Herndon’s Let Me Live—the list goes on. Prison writing is central to the Black literary canon and to our revolutionary practice as a people.

In this current moment, though, the book feels like an act of excavation. After Obama, a myth took hold that we had somehow “made it”—that Black people were now part of the mainstream, like the Irish or the Italians, absorbed into America. But that illusion hides the continuing reality of national oppression and the struggle for self-determination.

Shaka’s work reminds us: we’re still fighting. We’re still enslaved in many ways. We still seek liberation. The book insists on that truth.

And it isn’t just a historical document; it’s an intervention. The first section, “The Personal Is Political,” includes a brilliant essay on masculinity and community that cuts deeper than the usual surface-level debates we see in mass media. It pushes readers to think seriously about rebuilding our communities and confronting patriarchy through revolutionary transformation, not slogans.

At the same time, the book reasserts the perspective of the New African Nation—that Black people in the United States are a people with a history, a territory, and a right to self-definition. In an era where reactionary narratives seek to dissolve Black identity into a vague “American” category, that clarity is vital.

Beyond that, I love how Shaka’s writing shows the role of ideas in connecting struggles across borders. While listening to him earlier, I thought of Suchitra’s Midnight’s Borders—how literature bridges geographies. That’s why I insisted she had to read the book; her work, like his, helps build the intellectual infrastructure of internationalism.

Knowing that the Polis Project reaches audiences we never could—and vice versa—shows how these projects form bridges between movements.

Kate:

Thank you, Eugene. Shaka, I’d love for you to talk a bit more about your project—how it came about and why now.

Shaka:

All power to the people, and revolutionary greetings.

This book is the result of years of writing—some old, some new, some published before, others never seen. It reflects my ongoing theoretical and ideological development as I continue to mature politically in a changing world.

Comrades had been urging me for a long time to put my writings together, and when I met Derek and the rest of the team, we decided to collect selected essays and release them as one volume.

It felt timely. We wanted readers to trace the historical development of the New African Nation and the independence movement while connecting it to global struggles—the genocide in occupied Palestine, anti-colonial movements elsewhere, and the resistance behind prison walls.

The aim is to link the prison movement and abolition struggles to the broader revolutionary fight—nationally and internationally. There are conversations that must happen about political prisoners, revolutionary nationalism, socialism, abolition—what those words truly mean, and what they look like in communities of colour, in occupied communities, among LGBTQ people, across all struggles.

For me, writing has always been both survival and resistance. I’ve been confronting the state since I was fifteen—in juvenile halls, prisons, solitary confinement, supermax units. Writing became my weapon: a way to organise, to educate, to fight back, to stay human. That’s the tradition this project continues.

Kate:

Thank you, Shaka. That brings us naturally to the next question—about how governments systematise incarceration and use law itself as an instrument of warfare against communities that resist.

How do you see the law being used to criminalise political subjects, and what threats do those targeted actually pose to power?

Shaka:

If you study the origins of this country, you see that the law—so-called law—has always been a weapon of oppression. It’s been legitimised through force and violence, wielded in the interests of the ruling elite against the working class.

I often say this: when it comes to Black and white in America, we may sit at different distances from the fire, but we’re both feeling the heat. Oppression works in degrees, not absolutes.

From slavery through Jim Crow to mass incarceration, the law has served colonial and class politics. And now, look at how the state responds to protest. Young people take to the streets and are met with federal charges, harsher sentencing, and militarised policing—all meant to intimidate, to criminalise solidarity.

Support a liberation movement abroad, and they label you a terrorist sympathiser. Stand with Palestinians or with political prisoners, and they call it “material support for terrorism.” These laws are not about justice; they’re about fear.

Inside the prisons, the same system teaches us to police one another. They push “self-governance” models where prisoners are expected to control their peers. Refuse to comply, and you’re sent to harsher units, isolated, transferred far away. It’s control by another name.

What we’re seeing now—under Trump, but it goes beyond him—is an ideology of repression dressed up as patriotism. His administration only made visible what’s always been there. The bureaucrats and ideologues behind him—the Stephen Millers, the Steve Bannons—are the ones engineering it.

They federalise police, deploy ICE, and create an army of “private citizens” deputised to enforce state violence. They rip families apart under the rhetoric of “law and order” on land stolen from Indigenous people. That’s the contradiction at the heart of America.

To confront this system, we must strip away the illusion of legitimacy. Show that its origins are illegal and its application inhumane.

Kate:

Thank you, Shaka. We’re seeing those patterns everywhere—from the US to India to Palestine. Lamees, could you expand on what that looks like in your context?

Lamees:

Yes, absolutely. Even just looking at the recent ICE raids here in the US, you see how these tactics are designed not only to detain individuals but to frighten entire communities—immigrant leaders, union organisers, Muslim institutions, Palestine solidarity organisers.

The goal isn’t just punishment; it’s deterrence. When someone is taken, they’re often transferred to a facility thousands of miles away, cut off from family and community. It’s isolation as a weapon.

In occupied Palestine, it’s the same logic. The occupation can’t survive if there’s organised resistance, so it targets the very infrastructure of organising. By jailing leaders, killing writers, or even withholding the bodies of the dead, Israel tries to break the collective will to fight.

Take the case of Walid Daqqa, whom Kate mentioned earlier. He served his sentence while battling terminal cancer, denied medical treatment until he died. When illness didn’t kill him fast enough, the state extended his sentence—and even now refuses to release his body. That cruelty isn’t incidental; it’s strategic. Even his funeral, they fear, could spark collective mourning and unity.

And in Gaza today, that same system operates on a mass scale—indiscriminate arrests of doctors, journalists, community leaders. Families wait by buses to see if loved ones are among those released, often with no information, no closure. The aim is to destroy not just individuals but the possibility of continued resistance.

Shaka:

And that’s exactly why it’s important to make these connections. People think “it can’t happen here,” but we’re watching it happen every day in America. Just because the language is clinical—“detention,” “border enforcement”—doesn’t mean it’s any less violent than what’s called occupation elsewhere.

We’ve got to stop believing we can fight within the rules the state sets for us. You can’t call yourself revolutionary and still let the government define the terms of engagement.

We need dual power—our own infrastructures, our own systems of care and survival, and international solidarity that crosses those artificial boundaries. Because the assassinations, the disappearances, the murders through medical neglect—they’re happening here too. I’ve witnessed it for forty years.

Suchitra:

That’s exactly why we framed this event around the idea of carceral republics. Carcerality reproduces itself.

When we talk about Abu Ghraib or Guantánamo, what we’re really talking about is how the US invented the category of the “forever prisoner”—someone who can be held indefinitely, beyond the reach of due process. That logic of disappearance has been exported worldwide.

Israel has used administrative detention since 1948 to make Palestinians vanish. India uses the UAPA law the same way. And ICE now disappears people in the United States, moving them through detention networks where they cease to exist legally.

It’s not just prisons anymore. Entire communities are being caged. People stop leaving their homes out of fear. Carcerality extends beyond walls—it’s psychological, social, bureaucratic.

Many of India’s repressive laws, by the way, were modelled directly on the US Patriot Act. So the exchange of these tools is global.

At The Polis Project, when we talk about political prisoners, we’re not only referring to those physically behind bars. We mean the state’s power to disappear and dispossess people without process.

And now, with artificial intelligence and the rewriting of language itself, we face a new danger. Carcerality will extend to thought and expression. If our ability to write and articulate is eroded, then even imagination becomes imprisoned.

So our task is not only to document what’s happening locally but to see the patterns—the global architecture of disappearance and control that connects us all.

Kate:

Thank you all for that. What’s striking, listening to each of you, is how clearly the same structures repeat themselves — whether we’re talking about the UAPA in India, ICE in the United States, or Israel’s system of administrative detention. The form changes, but the logic remains: disappear, isolate, and dehumanise.

I want to talk now about how solidarity can exist within and beyond those systems. When the state works so hard to fragment resistance, how do we rebuild those connections?

Eugene:

That’s such an important question because isolation is central to repression. The goal isn’t only to punish individuals; it’s to make their struggle invisible to others.

One of the reasons Manifestations of Thought matters so much is that it cuts through that isolation. It shows that there are still people inside who are thinking, writing, and contributing to movement-building. These books become bridges — between prisoners and the outside, between past and present movements, and across borders.

When we lift up political prisoners, we’re not just talking about compassion; we’re talking about political clarity. Because they represent what the state fears most — people who have proven, by example, that liberation is possible.

That’s why solidarity campaigns matter. Even a letter, a book, a reading group that discusses these writings is part of that chain of resistance.

And we need to see these struggles as connected. When Palestinians read about George Jackson, when US prisoners hear about the BK-16 in India, those are acts of global consciousness. They remind us that none of these systems exists in isolation.

Suchitra:

Yes, and to build on that, solidarity also means learning from one another’s vocabularies.

When we started documenting Indian political prisoners, I was reading Palestinian prison literature. I was learning from how Palestinians wrote about confinement and survival. The metaphors of walls and cages became shared language.

In turn, our work in India has been read by activists in the US and Palestine, who see echoes of their own experience. That exchange of language becomes a form of collective resistance.

And this is something I want to emphasise: solidarity is not just moral support; it’s intellectual and emotional collaboration. It’s building archives, creating art, telling stories, and translating books — all of which assert that our lives are interconnected.

Lamees:

Exactly. For Palestinians, international solidarity has always been essential. Our struggle has survived for 76 years because people across the world have carried it forward — by protesting, by writing, by refusing silence.

But solidarity also means responsibility. It means studying our movements deeply, not just reposting slogans. It means asking how your liberation connects to ours — because it always does.

When we translated The Trinity of Fundamentals, it wasn’t only about preserving a text. It was about ensuring that someone in New York or Delhi or Johannesburg could read a story written under occupation and recognise part of themselves in it. That’s the foundation of solidarity — empathy turned into action.

Shaka:

I want to echo that. Real solidarity is about shared struggle, not sympathy.

When we talk about liberation, we can’t be selective. You can’t support freedom in one place and ignore oppression somewhere else. The same powers that occupy Palestine occupy Black communities here through policing, through poverty, through prisons.

We’ve got to break out of these boxes the system puts us in — race, nationality, religion — and see that we’re fighting the same enemy. That’s what they fear: unity.

Inside these walls, we study those connections. We read about Palestine, about India, about Haiti. We see ourselves reflected in all those struggles. And when I say “power to the people,” I mean all people fighting against colonialism, capitalism, and imperialism.

Kate:

That connection between study and solidarity feels like the thread running through all your work. I’d love to close by asking each of you: what does hope look like right now? How do you sustain it in the face of so much brutality?

Lamees:

For me, hope isn’t abstract. It’s in the act of continuing — continuing to translate, to write, to teach, to organise, even when it feels impossible.

I think about Wisam Rafidi writing The Trinity of Fundamentals on scraps of paper, knowing it might never leave his cell. That’s revolutionary hope — not optimism, but commitment.

Every time someone picks up that book or joins a demonstration or simply refuses to look away, that’s hope taking shape. It’s collective, not individual.

Suchitra:

I agree. Hope is not something the state can give or take away. It’s a practice — a discipline.

For me, hope comes from bearing witness, even when the stories are unbearable. It comes from knowing that people are still documenting, still writing, still building.

And it also comes from anger. I think we often mistake anger for despair, but in fact, righteous anger can be a profound form of hope. It says: “This is not the world we deserve, and I still believe we can build another.”

Eugene:

For me, hope lies in the fact that people keep resisting, even in the darkest times.

When we look back at the 1960s or 70s, it’s easy to romanticise the movements of that era. But those comrades faced the same repression, the same betrayals, the same exhaustion. And yet they kept going.

We’re part of that same lineage. Every new generation picks up the torch. That continuity is the most hopeful thing there is.

And when I see gatherings like this — people coming together to learn, to talk, to challenge — that tells me the movement isn’t dying. It’s evolving.

Shaka:

Hope is in struggle. It’s not something you wait for; it’s something you build.

Even behind these walls, we find it. In the smallest acts — sharing a book, helping a younger comrade study, refusing to give up your humanity.

As long as we keep resisting, hope lives.

Kate:

Thank you all for that. I think that’s the perfect note to end on — that hope is not passive, it’s active. It’s the daily decision to keep fighting, studying, building, and imagining together.

On behalf of The People’s Forum, thank you to Shaka Shakur, Lamees Mohammed, Suchitra Vijayan, and Eugene Puryear for this powerful conversation, and thank you to everyone here for listening, learning, and standing in solidarity.

All power to the people.