Patterns of Punishment: What Demolition Data Across Four Indian States Tells Us

Editor’s Note: This piece is written by Afreen Fatima, the researcher and writer behind The Demolitions Project, whose own home in Allahabad, in the North Indian state of Uttar Pradesh, was razed in retaliation for dissent. The dual position of the author, as both a documenter of systemic violence and a direct witness, grounds this work in data and lived experiences of the self and communities, connecting intimate dispossession to the broader machinery of state power.

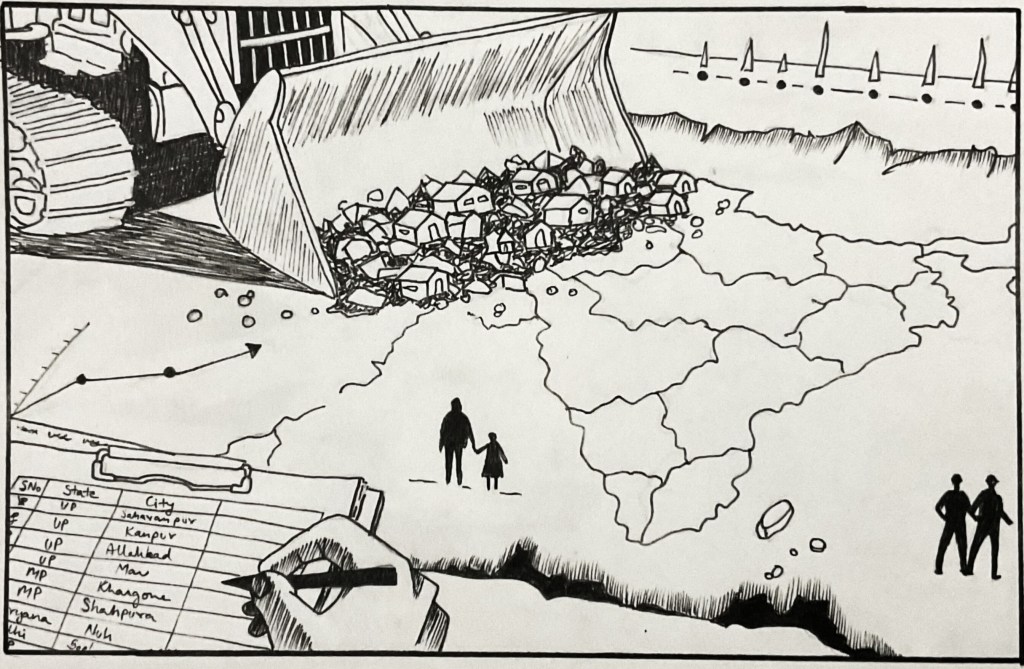

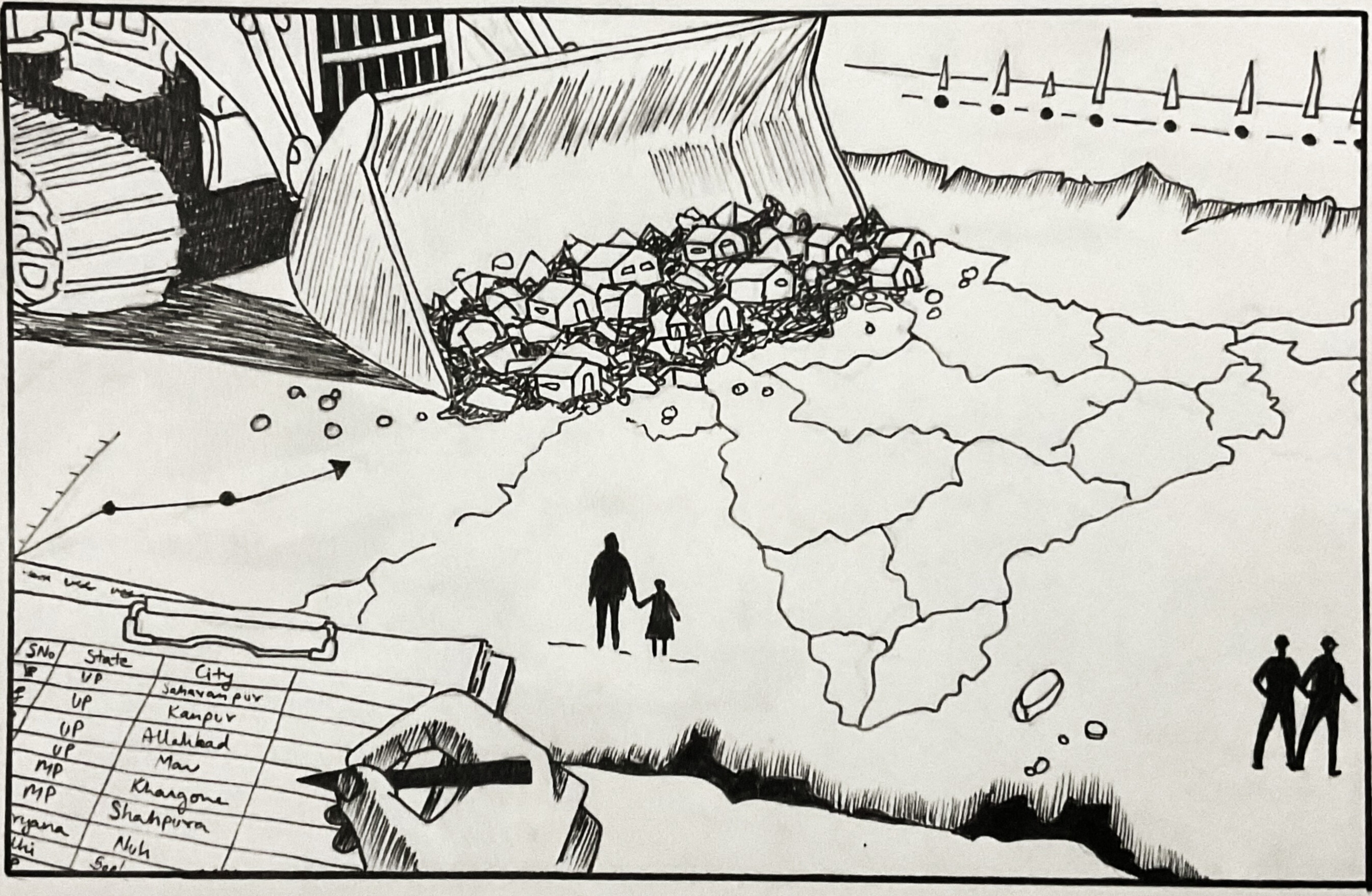

Across Indian cities and towns, bulldozers have become instruments of unchecked state power. Over recent years, authorities have demolished hundreds of Muslim homes, mosques, businesses, and community spaces—often without due process, or with little warning. This analysis draws from over five years of reportage, legal records, and interviews with those who lost everything, tracing demolitions across the northern states of Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, Haryana, and the national capital territory of Delhi.

Between 2019 and 2025, the Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) (sometimes in coalition) governed Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, and Haryana. Meanwhile, in Delhi, the Aam Aadmi Party remained in power until January 2025, but the BJP-led central (federal) government controlled the police, land, and public order in the national capital.

What emerges from the demolition data is stark and systematic. Over a thousand documented cases reveal a pattern of how the minority Muslim community is targeted through demolitions executed with public spectacle and impunity. This analysis highlights the political utility of demolition in contemporary India, especially in the northern part. It is a form of governance that works through fear, in contradiction to constitutional rights.

With the methodological foundation in our Demolitions Project, this data analysis reveals consistent patterns across the three states and one union territory, where demolition has evolved from a reactive administrative measure into a systemic exercise of political power and spatial violence.

Mapping Punitive Demolitions and Justifications

At first, the incidents may appear to be an ad hoc response to unrest, protest, or alleged crime. But trends across the documented cases and narratives expose the demolitions as a systemic method of disciplining dissent and marking entire communities disposable.

While the state justifications vary, from fighting the “land mafia” to responding to “riots” or taking action against “illegal” construction, the core logic remains that of collective retribution. In many cases, demolitions target the families and communities of accused individuals, often before such individuals are even convicted by courts, or before any legal process has begun.

The data is drawn from verified media reports, legal documents, testimonies of those affected, and civil society investigations, from May 2019 to August 2024.

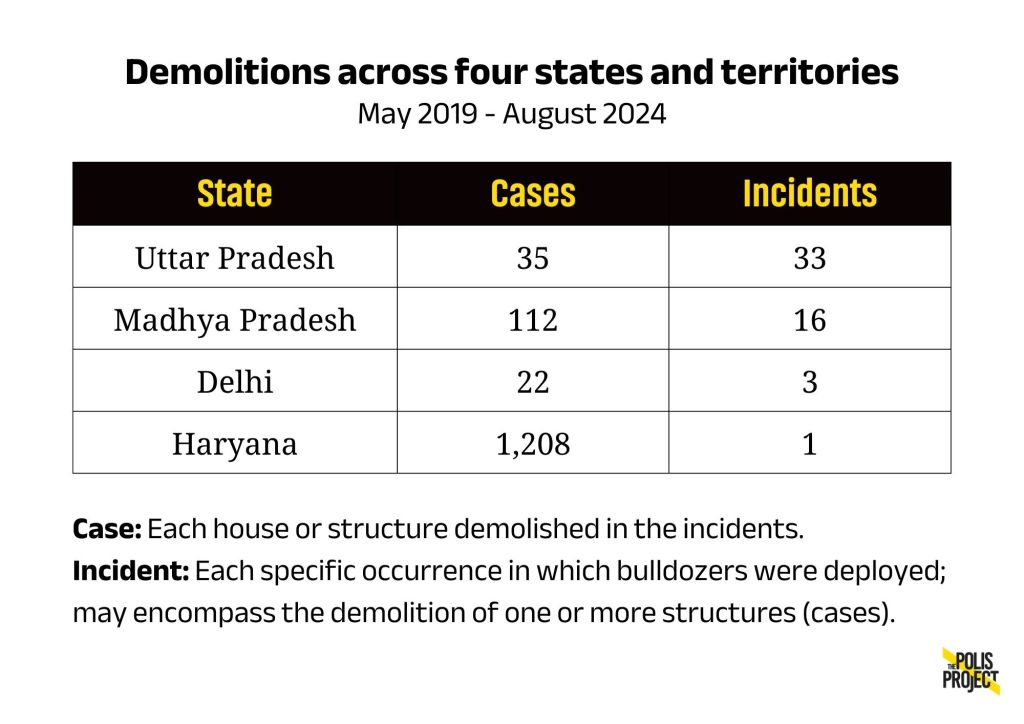

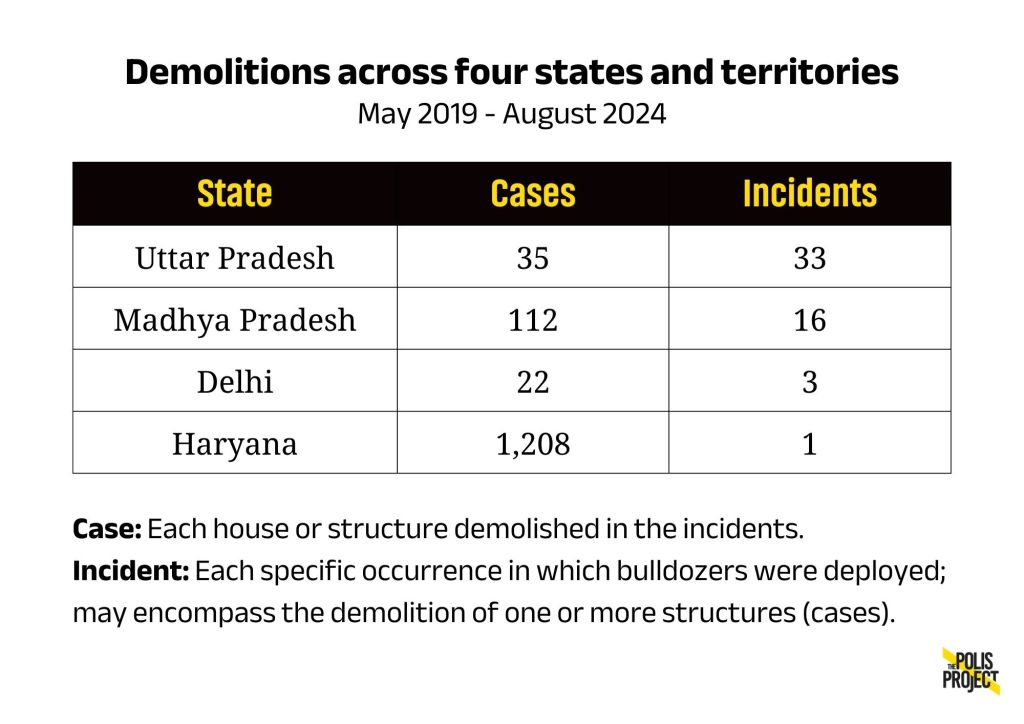

Across the four states, a total of 1,377 cases of demolitions were documented in 53 incidents of extrajudicial and punitive demolitions. Here, a ‘case’ refers to each house or structure demolished, and an ‘incident’ describes each specific occurrence in which bulldozers were deployed; an incident may encompass the demolition of one or more structures.

Uttar Pradesh leads in the occurrence of such demolitions with 33 incidents; it’s followed by Madhya Pradesh with 16, Delhi with three, and Haryana with one incident. However, Haryana leads in the number of cases, with 1,208 different structures, both residential and non-residential, demolished in one incident; it is followed by 112 cases in MP, 35 cases in Uttar Pradesh, and 22 cases in Delhi.

However, the 1,377 figure is almost certainly an undercount, as the database depends on coverage by media and civil society, which is uneven across regions, languages, and advocacy networks. Many incidents escape documentation altogether due to suppressed local reporting and the logistical and safety barriers of on-ground verification in hostile environments.

Further, in this analysis, a “Muslim” person, family, or community is identified primarily through descriptions in news reports, court documents, testimonies, and self-identification where available, which again reflects the limits and biases of public documentation.

The data can be organized under five broad categories based on how the state officially rationalizes the demolitions through shifting justifications: Gangster/Mafia, Political Opposition, Post “Riot” Action, Religious Targeting, and Crime and Punishment. The labels are drawn from official statements and media coverage that mask deeper patterns of collective retribution. It is further detailed in an earlier piece on the methodology of building the Demolitions Project.

- Gangster/Mafia: Framed as law-and-order enforcement against criminal networks, these demolitions raze homes, shops, and family properties of the accused before any trial. The “mafia” label lends the authorities a moral cover to bypass courts and extend punishment to relatives and acquaintances of accused individuals. Preliminary analysis of the data shows a clustering of demolitions under the gangster/mafia category in Uttar Pradesh.

- Political Opposition: Justified as actions against “illegal” properties, authorities have reportedly demolished the homes and offices of opposition leaders, activists, and protest organizers in the immediate aftermath of public mobilisations. This pattern is most evident in Uttar Pradesh; in four different incidents, individuals were targeted because they were members of an opposition party. These demolitions operate both as punishment and public warnings demarcating the limits of civil and political liberties.

- Post ‘Riot’ Action: Presented as an administrative response to communal violence or protests, these actions overwhelmingly target Muslim localities in the aftermath of clashes, functioning as collective punishment. Demolitions here function as a retaliatory script and a response to protests. The post “riot” action category shows a cluster of incidents in Madhya Pradesh, ruled by the BJP. Demolition incidents in Haryana and Delhi are too few to analyze the concentration of a category in these areas. But even in these fewer recorded instances, the number of structures demolished is relatively high. This is especially visible in instances following political dissent or communal violence, such as demolitions in Jahangirpuri, Delhi, after communal tension rose, and demolitions in Khargone, Madhya Pradesh, following violence during the Hindu festival of Ram Navami. Uttar Pradesh saw state-wide demolitions framed as a drive against illegal structures and encroachment in mid-2022. This happened after Muslims protested against objectionable remarks by right-wing Hindu commentator Nupur Sharma in Uttar Pradesh’s Saharanpur, Kanpur, and Allahabad.

I had earlier reported on how Mohammad Bilal’s house was demolished in Saharanpur as part of this crackdown. Police arrived at his home in the afternoon and bulldozed the front part of the house without prior notice, even as family members remained inside. The demolition was folded into a series of post-protest “anti-encroachment” drives, enabling the administration to recast punitive retaliation as routine civic enforcement. - Crime and Punishment: Offered as neutral enforcement of building codes or municipal laws, these incidents ignore legal procedures or retrofit them post-demolition; “illegality” of structures is deployed as a convenient afterthought to legitimize punitive intent. These categories, while varying by state, reveal a consistent logic: demolitions as preemptive discipline, where state rhetoric normalizes extrajudicial force against marked communities. An example in this category would be the demolition of Shama Begum’s home in Shahpura, Madhya Pradesh, after her son eloped with a Hindu woman and was accused of “kidnapping” and “love jihad”. In that case, the administration framed the family’s long-standing, patta-holding house as “illegal” encroachment and folded the demolition into routine enforcement, turning what was in effect punishment for an interfaith relationship into a spectacle of supposedly neutral crime control.

- Religious Targeting: This category rationalizes targeted demolitions as the removal of encroachments or unauthorized religious structures. It selectively levels mosques, dargahs (shrines), churches, and Muslim homes framed as threats, exposing the explicitly majoritarian bias in enforcement.

In Delhi, for instance, among three incidents, two targeted a mosque and a Muslim man whose home was arbitrarily demolished. In the case of the mosque in Mangalpuri, the civic body demolished a boundary wall adjoining the mosque, citing “encroachment” under heavy security deployment. It stopped after locals protested. These incidents expose the ease with which the Muslim spaces are framed as encroachments or security threats.

It is imperative to note that all demolitions that target Muslims are part of the ‘religious targeting’ category because the underlying reason for the demolitions is the victim’s religious identity, and not merely participation in protests or having a criminal history. I have used these categories for highlighting the different reasons used to justify such a demolition by the media. The reportage implies that because someone is a “protestor” or “rioter” or “gangster”, it is acceptable to bypass established legal procedures.

Core Patterns of Punitive Demolitions

While compiling data for the Demolitions Database, certain patterns leaped out.

Identity: Overwhelmingly, the homes reduced to rubble belong to Muslims, often the poorest or the most outspoken among them.

When the locations of each demolition are mapped, they significantly overlap with places of minority concentrations or areas where marginalized voices publicly protested. The pattern is so pronounced that even courts started to take notice. For instance, in Haryana’s Nuh district last year, over 1,215 homes and shops were razed in just five days in the aftermath of communal clashes, “the overwhelming majority of these belonged to Muslims”. The Punjab and Haryana High Court intervened, bluntly asking the administration whether this was “an exercise of ethnic cleansing”. That phrase, ethnic cleansing, lingers in the air. When the judiciary uses such language, it’s an admission that these demolitions are not random or simply administrative; they are targeted and punitive.

Element of surprise and speed: Time and again, families described how quickly the bulldozers arrived after a triggering incident, leaving no chance for defense. In my own case, wherein my family home was demolished in Allahabad, the bulldozer was at our door barely a day after authorities falsely accused my father of masterminding a local protest against objectionable remarks by right–wing commentator and then BJP spokesperson Nupur Sharma.

In numerous cases across Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, and Delhi, I documented a similar timeline: a protest or alleged “riot” occurs or an alleged crime is committed; officials publicly blame members of a certain community; within 24-48 hours, bulldozers show up at the homes of the accused and even suspected sympathizers.

The legal process is bypassed entirely, violating the right to due process. Demolition notices, if given at all, are backdated or served right before the demolition. One elderly man in Uttar Pradesh recounted how, in March 2023, his neighbors saw officials pasting a notice on his wall and photographing it, only to peel it off and leave without a word; hours later, the bulldozer came. His family never even got to read what was on that paper. This has emerged as the modus operandi—a perfunctory paperwork to claim legality, executed to prevent any real contestation. When challenged, authorities often claim the structures were “illegal” constructions lacking permits, but if that was genuinely the issue, due process (notice, hearings, time to appeal, and relocation) would be followed. Instead, the pattern is extrajudicial haste, a sign that the real motive is punishment, not civic compliance.

Public spectacle: The state’s logic in these cases is laid bare by the spectacle they make of it. Uttar Pradesh’s Chief Minister and BJP leader, Ajay Singh Bisht, openly revels in the moniker “Bulldozer Baba.” After the 2023 killing of Umesh Pal, a witness to the political murder of Raju Pal, Bisht declared in the state assembly: “Mitti me mila denge (We will reduce them to dust)”, effectively signaling that bulldozers would be unleashed on any properties linked (even tenuously) to the suspects. True to his word, in the following weeks, bulldozers tore through multiple homes of individuals allegedly linked to late gangster-turned-politician Ateeq Ahmad, who was purportedly behind the said political murder. It happened without legal orders or hearings, with TV news anchors cheering this on as swift justice. What we see here and in several other cases is demolition as performance, a theater of power where the message is that the ruler’s will is law. The bulldozer becomes a stage prop in political rallies and propaganda, symbolizing an aggressive state that doesn’t bother with courts and trials. Meanwhile, a majority of the public, indoctrinated by a sensational media, celebrates this approach, especially when it’s framed as a crackdown on “rioters” or “criminals”.

The entire act, from scapegoating a marginalized community to razing their properties, has been justified and normalized as a political spectacle. The state machinery, from local development authorities to cabinet ministers, closes ranks to defend arbitrary demolitions ordered by powerful officials. In other words, the rule of law has inverted; the measure of successful governance is not adherence to law and duty, but enforcement of a certain majoritarian political will.

Law as afterthought: After closely documenting dozens of cases, I could map the blueprint of how authorities bend laws to their will. Typically, municipal or development authority laws require prior notice (often 15 days) for any demolition due to illegal construction. They also allow appeals. What we see instead is a gross subversion of these safeguards.

In case after case, families either never received a notice or were shown a notice only after the demolition. Many later filed Right to Information (RTI) applications to obtain copies of the demolition orders or notices. The answers were telling. In Uttar Pradesh, a family had to file an RTI in 2023 to see the notice that authorities claimed to have issued. Months later, no response was received, which they mentioned in their petition challenging the demolition. Another family also filed an RTI the same year for the demolition order, and the agency bizarrely wrote back saying, “your son wants your house demolition notice”; the son was the legal owner of the house, but his father was accused of being an aide to a gangster, and their home was demolished. The family received no official copy of anything, and their case in the high court has not seen a single hearing to date. The state retrofits legality after the act, if at all. It counts on the slow courts and the burden of proof being on the victim to cover its tracks.

Through all these emerging patterns, one can discern the logic of power at play. Demolition drives are a form of collective punishment primarily aimed at Muslims, delivering instant retribution for dissent or suspected crime, along with a political message. The message to the minority community is that the state can take away your home, your shelter, your memories, at any time, and no one can stop it. The message to the majority of BJP government supporters is that a certain “justice” is being delivered to the community portrayed as their “enemy”. As MP Chief Minister Shivraj Singh Chauhan put it, “The bulldozer is not demolishing properties of innocent people, it is only demolishing properties of rioters and criminals.”

The pattern shows performativity over procedure. The bulldozer’s roar says what the state wants and what many politicians from the ruling regime openly propagate. For instance, Madhya Pradesh Home Minister Narottam Misha’s threat after the Khargone clash: “Jis ghar se patthar aaye hain, us ghar ko hi patthar ka dher banayenge (the houses from where stones were pelted will be turned to rubble)”. Or Madhya Pradesh BJP in-charge Muralidhar Rao’s promise that “stone-pelters will be greeted with a bulldozer.” These chilling pledges signal that if someone is a Muslim and they “misbehave” (meaning, you protest, dissent, or simply exist in a way the state dislikes), those in power will crush the individuals and the spaces they inhabit.

In the very beginning of the Demolitions Project, we asked: Who can punish? The answer emerges to be those in power with law and order at their command. And who can be punished? Those whom the state marks as expendable or threatening to the hegemonic order. In India today, that often means Muslims, Dalits, the poor, and anyone who doesn’t fit the vision of Hindu supremacy.

Reading Data as Evidence

The data and narratives show a chillingly consistent modus operandi behind India’s extrajudicial demolitions. These stories reveal demolition as a language of power, a form of spatial punishment through which the state performs control. What we are witnessing is not a breakdown of the rule of law but a reconfiguration of it where legality is bent to serve political ends. As the bulldozer becomes an instrument of ideological control, perhaps shining a light on its trail could be the first step in dismantling the machinery of impunity.

In our Demolitions Project, the interactive mapping and the accompanying narrative profiles reveal the underlying continuity between these acts. Despite being carried out by different state governments and under various local bureaucracies, the demolitions follow a similar script: a rapid mobilization of bulldozers, selective application of building codes, retroactive notices, and the absence of any meaningful legal recourse. This uniformity suggests coordination beyond coincidence; it is an ideological template masquerading as law enforcement. In my own case, this script was followed to the letter. The demolition notice arrived late and was misaddressed; the demolition happened without a court hearing, and its justification was tied to a protest. My family was punished, not through courts but with a bulldozer.

Against this backdrop, the data helps one connect the intimate violence of loss with the structural violence of policy. It functions as an evidentiary foundation for understanding the broader logic of punitive governance and spatial violence. The patterns emerging through the data enable us to see the demolitions not as isolated incidents but as part of a broader punitive architecture in which the minority community’s home becomes a site of both belonging and dispossession.

Note: More about the politics of demolitions will be explored by the author in two upcoming pieces, including a detailed auto-ethnographic essay on her own home being demolished. Watch this space for more updates.

Related Posts

Patterns of Punishment: What Demolition Data Across Four Indian States Tells Us

Editor’s Note: This piece is written by Afreen Fatima, the researcher and writer behind The Demolitions Project, whose own home in Allahabad, in the North Indian state of Uttar Pradesh, was razed in retaliation for dissent. The dual position of the author, as both a documenter of systemic violence and a direct witness, grounds this work in data and lived experiences of the self and communities, connecting intimate dispossession to the broader machinery of state power.

Across Indian cities and towns, bulldozers have become instruments of unchecked state power. Over recent years, authorities have demolished hundreds of Muslim homes, mosques, businesses, and community spaces—often without due process, or with little warning. This analysis draws from over five years of reportage, legal records, and interviews with those who lost everything, tracing demolitions across the northern states of Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, Haryana, and the national capital territory of Delhi.

Between 2019 and 2025, the Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) (sometimes in coalition) governed Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, and Haryana. Meanwhile, in Delhi, the Aam Aadmi Party remained in power until January 2025, but the BJP-led central (federal) government controlled the police, land, and public order in the national capital.

What emerges from the demolition data is stark and systematic. Over a thousand documented cases reveal a pattern of how the minority Muslim community is targeted through demolitions executed with public spectacle and impunity. This analysis highlights the political utility of demolition in contemporary India, especially in the northern part. It is a form of governance that works through fear, in contradiction to constitutional rights.

With the methodological foundation in our Demolitions Project, this data analysis reveals consistent patterns across the three states and one union territory, where demolition has evolved from a reactive administrative measure into a systemic exercise of political power and spatial violence.

Mapping Punitive Demolitions and Justifications

At first, the incidents may appear to be an ad hoc response to unrest, protest, or alleged crime. But trends across the documented cases and narratives expose the demolitions as a systemic method of disciplining dissent and marking entire communities disposable.

While the state justifications vary, from fighting the “land mafia” to responding to “riots” or taking action against “illegal” construction, the core logic remains that of collective retribution. In many cases, demolitions target the families and communities of accused individuals, often before such individuals are even convicted by courts, or before any legal process has begun.

The data is drawn from verified media reports, legal documents, testimonies of those affected, and civil society investigations, from May 2019 to August 2024.

Across the four states, a total of 1,377 cases of demolitions were documented in 53 incidents of extrajudicial and punitive demolitions. Here, a ‘case’ refers to each house or structure demolished, and an ‘incident’ describes each specific occurrence in which bulldozers were deployed; an incident may encompass the demolition of one or more structures.

Uttar Pradesh leads in the occurrence of such demolitions with 33 incidents; it’s followed by Madhya Pradesh with 16, Delhi with three, and Haryana with one incident. However, Haryana leads in the number of cases, with 1,208 different structures, both residential and non-residential, demolished in one incident; it is followed by 112 cases in MP, 35 cases in Uttar Pradesh, and 22 cases in Delhi.

However, the 1,377 figure is almost certainly an undercount, as the database depends on coverage by media and civil society, which is uneven across regions, languages, and advocacy networks. Many incidents escape documentation altogether due to suppressed local reporting and the logistical and safety barriers of on-ground verification in hostile environments.

Further, in this analysis, a “Muslim” person, family, or community is identified primarily through descriptions in news reports, court documents, testimonies, and self-identification where available, which again reflects the limits and biases of public documentation.

The data can be organized under five broad categories based on how the state officially rationalizes the demolitions through shifting justifications: Gangster/Mafia, Political Opposition, Post “Riot” Action, Religious Targeting, and Crime and Punishment. The labels are drawn from official statements and media coverage that mask deeper patterns of collective retribution. It is further detailed in an earlier piece on the methodology of building the Demolitions Project.

- Gangster/Mafia: Framed as law-and-order enforcement against criminal networks, these demolitions raze homes, shops, and family properties of the accused before any trial. The “mafia” label lends the authorities a moral cover to bypass courts and extend punishment to relatives and acquaintances of accused individuals. Preliminary analysis of the data shows a clustering of demolitions under the gangster/mafia category in Uttar Pradesh.

- Political Opposition: Justified as actions against “illegal” properties, authorities have reportedly demolished the homes and offices of opposition leaders, activists, and protest organizers in the immediate aftermath of public mobilisations. This pattern is most evident in Uttar Pradesh; in four different incidents, individuals were targeted because they were members of an opposition party. These demolitions operate both as punishment and public warnings demarcating the limits of civil and political liberties.

- Post ‘Riot’ Action: Presented as an administrative response to communal violence or protests, these actions overwhelmingly target Muslim localities in the aftermath of clashes, functioning as collective punishment. Demolitions here function as a retaliatory script and a response to protests. The post “riot” action category shows a cluster of incidents in Madhya Pradesh, ruled by the BJP. Demolition incidents in Haryana and Delhi are too few to analyze the concentration of a category in these areas. But even in these fewer recorded instances, the number of structures demolished is relatively high. This is especially visible in instances following political dissent or communal violence, such as demolitions in Jahangirpuri, Delhi, after communal tension rose, and demolitions in Khargone, Madhya Pradesh, following violence during the Hindu festival of Ram Navami. Uttar Pradesh saw state-wide demolitions framed as a drive against illegal structures and encroachment in mid-2022. This happened after Muslims protested against objectionable remarks by right-wing Hindu commentator Nupur Sharma in Uttar Pradesh’s Saharanpur, Kanpur, and Allahabad.

I had earlier reported on how Mohammad Bilal’s house was demolished in Saharanpur as part of this crackdown. Police arrived at his home in the afternoon and bulldozed the front part of the house without prior notice, even as family members remained inside. The demolition was folded into a series of post-protest “anti-encroachment” drives, enabling the administration to recast punitive retaliation as routine civic enforcement. - Crime and Punishment: Offered as neutral enforcement of building codes or municipal laws, these incidents ignore legal procedures or retrofit them post-demolition; “illegality” of structures is deployed as a convenient afterthought to legitimize punitive intent. These categories, while varying by state, reveal a consistent logic: demolitions as preemptive discipline, where state rhetoric normalizes extrajudicial force against marked communities. An example in this category would be the demolition of Shama Begum’s home in Shahpura, Madhya Pradesh, after her son eloped with a Hindu woman and was accused of “kidnapping” and “love jihad”. In that case, the administration framed the family’s long-standing, patta-holding house as “illegal” encroachment and folded the demolition into routine enforcement, turning what was in effect punishment for an interfaith relationship into a spectacle of supposedly neutral crime control.

- Religious Targeting: This category rationalizes targeted demolitions as the removal of encroachments or unauthorized religious structures. It selectively levels mosques, dargahs (shrines), churches, and Muslim homes framed as threats, exposing the explicitly majoritarian bias in enforcement.

In Delhi, for instance, among three incidents, two targeted a mosque and a Muslim man whose home was arbitrarily demolished. In the case of the mosque in Mangalpuri, the civic body demolished a boundary wall adjoining the mosque, citing “encroachment” under heavy security deployment. It stopped after locals protested. These incidents expose the ease with which the Muslim spaces are framed as encroachments or security threats.

It is imperative to note that all demolitions that target Muslims are part of the ‘religious targeting’ category because the underlying reason for the demolitions is the victim’s religious identity, and not merely participation in protests or having a criminal history. I have used these categories for highlighting the different reasons used to justify such a demolition by the media. The reportage implies that because someone is a “protestor” or “rioter” or “gangster”, it is acceptable to bypass established legal procedures.

Core Patterns of Punitive Demolitions

While compiling data for the Demolitions Database, certain patterns leaped out.

Identity: Overwhelmingly, the homes reduced to rubble belong to Muslims, often the poorest or the most outspoken among them.

When the locations of each demolition are mapped, they significantly overlap with places of minority concentrations or areas where marginalized voices publicly protested. The pattern is so pronounced that even courts started to take notice. For instance, in Haryana’s Nuh district last year, over 1,215 homes and shops were razed in just five days in the aftermath of communal clashes, “the overwhelming majority of these belonged to Muslims”. The Punjab and Haryana High Court intervened, bluntly asking the administration whether this was “an exercise of ethnic cleansing”. That phrase, ethnic cleansing, lingers in the air. When the judiciary uses such language, it’s an admission that these demolitions are not random or simply administrative; they are targeted and punitive.

Element of surprise and speed: Time and again, families described how quickly the bulldozers arrived after a triggering incident, leaving no chance for defense. In my own case, wherein my family home was demolished in Allahabad, the bulldozer was at our door barely a day after authorities falsely accused my father of masterminding a local protest against objectionable remarks by right–wing commentator and then BJP spokesperson Nupur Sharma.

In numerous cases across Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, and Delhi, I documented a similar timeline: a protest or alleged “riot” occurs or an alleged crime is committed; officials publicly blame members of a certain community; within 24-48 hours, bulldozers show up at the homes of the accused and even suspected sympathizers.

The legal process is bypassed entirely, violating the right to due process. Demolition notices, if given at all, are backdated or served right before the demolition. One elderly man in Uttar Pradesh recounted how, in March 2023, his neighbors saw officials pasting a notice on his wall and photographing it, only to peel it off and leave without a word; hours later, the bulldozer came. His family never even got to read what was on that paper. This has emerged as the modus operandi—a perfunctory paperwork to claim legality, executed to prevent any real contestation. When challenged, authorities often claim the structures were “illegal” constructions lacking permits, but if that was genuinely the issue, due process (notice, hearings, time to appeal, and relocation) would be followed. Instead, the pattern is extrajudicial haste, a sign that the real motive is punishment, not civic compliance.

Public spectacle: The state’s logic in these cases is laid bare by the spectacle they make of it. Uttar Pradesh’s Chief Minister and BJP leader, Ajay Singh Bisht, openly revels in the moniker “Bulldozer Baba.” After the 2023 killing of Umesh Pal, a witness to the political murder of Raju Pal, Bisht declared in the state assembly: “Mitti me mila denge (We will reduce them to dust)”, effectively signaling that bulldozers would be unleashed on any properties linked (even tenuously) to the suspects. True to his word, in the following weeks, bulldozers tore through multiple homes of individuals allegedly linked to late gangster-turned-politician Ateeq Ahmad, who was purportedly behind the said political murder. It happened without legal orders or hearings, with TV news anchors cheering this on as swift justice. What we see here and in several other cases is demolition as performance, a theater of power where the message is that the ruler’s will is law. The bulldozer becomes a stage prop in political rallies and propaganda, symbolizing an aggressive state that doesn’t bother with courts and trials. Meanwhile, a majority of the public, indoctrinated by a sensational media, celebrates this approach, especially when it’s framed as a crackdown on “rioters” or “criminals”.

The entire act, from scapegoating a marginalized community to razing their properties, has been justified and normalized as a political spectacle. The state machinery, from local development authorities to cabinet ministers, closes ranks to defend arbitrary demolitions ordered by powerful officials. In other words, the rule of law has inverted; the measure of successful governance is not adherence to law and duty, but enforcement of a certain majoritarian political will.

Law as afterthought: After closely documenting dozens of cases, I could map the blueprint of how authorities bend laws to their will. Typically, municipal or development authority laws require prior notice (often 15 days) for any demolition due to illegal construction. They also allow appeals. What we see instead is a gross subversion of these safeguards.

In case after case, families either never received a notice or were shown a notice only after the demolition. Many later filed Right to Information (RTI) applications to obtain copies of the demolition orders or notices. The answers were telling. In Uttar Pradesh, a family had to file an RTI in 2023 to see the notice that authorities claimed to have issued. Months later, no response was received, which they mentioned in their petition challenging the demolition. Another family also filed an RTI the same year for the demolition order, and the agency bizarrely wrote back saying, “your son wants your house demolition notice”; the son was the legal owner of the house, but his father was accused of being an aide to a gangster, and their home was demolished. The family received no official copy of anything, and their case in the high court has not seen a single hearing to date. The state retrofits legality after the act, if at all. It counts on the slow courts and the burden of proof being on the victim to cover its tracks.

Through all these emerging patterns, one can discern the logic of power at play. Demolition drives are a form of collective punishment primarily aimed at Muslims, delivering instant retribution for dissent or suspected crime, along with a political message. The message to the minority community is that the state can take away your home, your shelter, your memories, at any time, and no one can stop it. The message to the majority of BJP government supporters is that a certain “justice” is being delivered to the community portrayed as their “enemy”. As MP Chief Minister Shivraj Singh Chauhan put it, “The bulldozer is not demolishing properties of innocent people, it is only demolishing properties of rioters and criminals.”

The pattern shows performativity over procedure. The bulldozer’s roar says what the state wants and what many politicians from the ruling regime openly propagate. For instance, Madhya Pradesh Home Minister Narottam Misha’s threat after the Khargone clash: “Jis ghar se patthar aaye hain, us ghar ko hi patthar ka dher banayenge (the houses from where stones were pelted will be turned to rubble)”. Or Madhya Pradesh BJP in-charge Muralidhar Rao’s promise that “stone-pelters will be greeted with a bulldozer.” These chilling pledges signal that if someone is a Muslim and they “misbehave” (meaning, you protest, dissent, or simply exist in a way the state dislikes), those in power will crush the individuals and the spaces they inhabit.

In the very beginning of the Demolitions Project, we asked: Who can punish? The answer emerges to be those in power with law and order at their command. And who can be punished? Those whom the state marks as expendable or threatening to the hegemonic order. In India today, that often means Muslims, Dalits, the poor, and anyone who doesn’t fit the vision of Hindu supremacy.

Reading Data as Evidence

The data and narratives show a chillingly consistent modus operandi behind India’s extrajudicial demolitions. These stories reveal demolition as a language of power, a form of spatial punishment through which the state performs control. What we are witnessing is not a breakdown of the rule of law but a reconfiguration of it where legality is bent to serve political ends. As the bulldozer becomes an instrument of ideological control, perhaps shining a light on its trail could be the first step in dismantling the machinery of impunity.

In our Demolitions Project, the interactive mapping and the accompanying narrative profiles reveal the underlying continuity between these acts. Despite being carried out by different state governments and under various local bureaucracies, the demolitions follow a similar script: a rapid mobilization of bulldozers, selective application of building codes, retroactive notices, and the absence of any meaningful legal recourse. This uniformity suggests coordination beyond coincidence; it is an ideological template masquerading as law enforcement. In my own case, this script was followed to the letter. The demolition notice arrived late and was misaddressed; the demolition happened without a court hearing, and its justification was tied to a protest. My family was punished, not through courts but with a bulldozer.

Against this backdrop, the data helps one connect the intimate violence of loss with the structural violence of policy. It functions as an evidentiary foundation for understanding the broader logic of punitive governance and spatial violence. The patterns emerging through the data enable us to see the demolitions not as isolated incidents but as part of a broader punitive architecture in which the minority community’s home becomes a site of both belonging and dispossession.

Note: More about the politics of demolitions will be explored by the author in two upcoming pieces, including a detailed auto-ethnographic essay on her own home being demolished. Watch this space for more updates.

SUPPORT US

We like bringing the stories that don’t get told to you. For that, we need your support. However small, we would appreciate it.