Judicial and administrative accountability in cases of custodial deaths in India (2015-2016) – 1

“In our great democracy, peacekeepers are given a free rein and are a law unto themselves.”

T.J. Joseph, A Thousand Cuts.

On 19 June 2020, during the COVID-19 pandemic in India, 59 year old Jeyaraj and his 31-year -old son Bennix were picked up by the Tamil Nadu Police from Sathankulam, Thoothukudi district in Tamil Nadu. The Police claim that the duo kept their mobile accessories shop open beyond permissible hours and violated the Indian government’s COVID-19 lockdown rules. They were tortured and sexually assaulted in police custody, which resulted in their deaths, or in other words, in institutional murder. The term custody refers to apprehending someone for protective care.

In November 2021, in the state of Uttar Pradesh, 22-year-old Altaf died in police custody. According to the Police, he asked to go to the washroom while he was being questioned and hung himself from the water pipeline using the string of the hood of his jacket. According to the Union government, Uttar Pradesh reported the highest number of custodial deaths among all states and Union Territories with 451 custodial deaths in 2020-2021, and 501 in 2021-2022.

In the last week of July and the first week of August in 2022, four Muslim men – Abdul Rajjak, Jiyaul Laskar, Akbar Khan and Saidul Munsi were reported to have died in judicial custody at the Baruipur Central Correctional Home, South 24 Parganas district, West Bengal. All the four men had been picked up by the West Bengal police in separate cases in the last week of July 2022. West Bengal registered the second highest number of custodial deaths during 2020-2021 (185 in 2020 and 257 in 2021).

Instances of custodial violence and torture abound the criminal justice landscape in India. According to political scientist and legal scholar Jinee Lokaneeta, the Police in postcolonial India have often been accused of using torture or third-degree interrogation in both routine and exceptional criminal cases and have been deemed responsible for hundreds of custodial deaths each year. News articles, reports by human rights organizations, journalistic investigations and data shared by the Government of India, all substantiate this fact. Yet, such crimes have not been addressed, proposed reforms have not been implemented and custodial violence and torture are considered to be a routine part of the Indian criminal justice system.

How and why has torture become a routine part of routine police procedure in liberal democracies? Anthropologist Veena Das addresses this question in her article describing Innocent Prisoners (2021), a book by Abdul Wahid Sheikh that details the wrongful incarceration of innocent prisoners in India. For Das, to tackle the disorders of democracy that challenge classical theories of state formation and governance, it is crucial to engage with scholarly works by journalists, schoolteachers and lawyers. While these sources are not commonly considered by academic theory, they provide insights into the working of the State machinery and Police biases vis-a-vis torture in India. Also, in Slum Acts (2022), Das asks: What are the limits of permissible and non-permissible forms or acts of violence? How do we distinguish between the ‘barbaric’ and ‘civilized’ forms of violence?

When we shift the focus to the context of custodial deaths, how does Police torture become ‘necessary’ and therefore ‘civilized’ within our conceptions of democracies? Scholar Upendra Baxi argues that torture is institutionalized in India and custodial violence and torture are an integral part of police operations. Lawyer Nitya Ramakrishnan in In Custody: Law, Impunity and Prisoner Abuse in South Asia notes that in Indian society the concepts of justice and torture are inextricable: “torture becomes a fantasy of justice.”

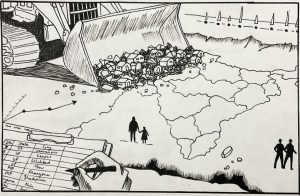

Why are custodial deaths – an urgent issue – not given enough importance? Why are strict measures not taken? To understand questions of accountability and impunity in the context of custodial deaths in India, we look at a few cases that have received limited public attention. Most of the victims of custodial deaths belong to religious minorities, Scheduled Castes (SC) and Other Backward Castes communities. They come from various parts of the country, from underprivileged and oppressed backgrounds and they all died in 2015 and 2016, in either police or judicial custody. They are: Minhaj Ansari, P. Ramkumar, Shameel Basha, Meenkulambu Karthik, Kuppuswamy, Mohan, N. Gokulakannan, Bujji, Sheikh Hyder, Viqaruddin Ahmed, G.Bonappa, N. Padma, T. Lakshman, Obaidur Rahman and Bhushan Deshmukh.

We look at these cases to understand the nature of ongoing impunity enjoyed by various law enforcement agencies and the complicity of both state and non-state institutions. We specifically look at cases from 2015 and 2016 since enough time has passed to analyze whether any measures of accountability have been taken, keeping in mind the pace of the Indian criminal justice system.

Ample evidence points to the Police as perpetrators of state violence when denying or taking away a person’s right to life and personal liberty. The Police in India are in charge of crime control, investigations as well as law and order. Policing is subject to Article 246 of the Indian Constitution and each Indian state can set its own rules for police recruitment and governance. Despite states’ autonomy to organize their policing, police bodies remain modeled on the Police Act of 1861, promulgated by the British. While states have different statues, there are features that are common to all of them. Most police statutes recognize dereliction of duty as of service misconduct and invite disciplinary action against officers in whose custody prisoners have died. Officers who are charged with a prima facie case of custodial rape invite disciplinary action as per most police statutes. Custodial deaths, which occur when a person is either in judicial or police custody, are a common result of torture, which is a part of routine police procedure in India.

*

While various legal frameworks and measures have been proposed over the last few decades to act on torture by public officials, they have not been implemented yet.

Since 14 October 1997, India has been a signatory to the United Nation’s Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment but has yet to ratify this crucial international human rights instrument. In April 2010, the The Prevention of Torture Bill, 2010 was introduced in India’s lower house of Parliament, the Lok Sabha, passed in the house and referred to the upper house of Parliament. The select committee constituted to prepare a report on the bill and to help ratify its commitment to the Convention against Torture presented its findings in December 2010. In October 2017, the Law Commission of India published their report titled Implementation of ‘United Nations Convention against Torture and other Cruel, Inhuman and Degrading Treatment or Punishment’ through Legislation. This report was then introduced in the Rajya Sabha as a private member bill on 15 December 2017 as the Prevention of Torture Bill, 2017 , but was not enacted. The same bill was introduced again in the Lok Sabha on 9 February 2018 as a private member bill, but since then both bills have lapsed. A modified bill called the Prevention of Torture and Atrocities (By Public Servants) Bill, 2019 was introduced in the Lok Sabha in December 2021 and is pending and no legislation has been passed to define, condemn and take action against torture by public officials in India.

*

Despite existing legal frameworks that guarantee and protect the rights of prisoners, custodial deaths and torture often go unpunished in India. According to the Indian National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB – India’s only official statistics on crime), in 2017 about 100 people died in police custody, but there were no convictions. In 62 cases of these custodial deaths, 33 police personnel were arrested, 27 were charge-sheeted, four were acquitted or discharged and none were convicted. In addition, the NCRB also recorded “56 cases against police personnel for human rights violations. In total, 57 police officers were arrested, 48 charge-sheeted, and only three convicted.” Numbers show that in the 18 years between 2001 and 2018, only 810 cases were registered, 334 charge-sheeted and only 26 police personnel were convicted. This abysmally low rate of conviction and accountability among the Police exists in a democracy where citizens are guaranteed the right to life and personal liberty.

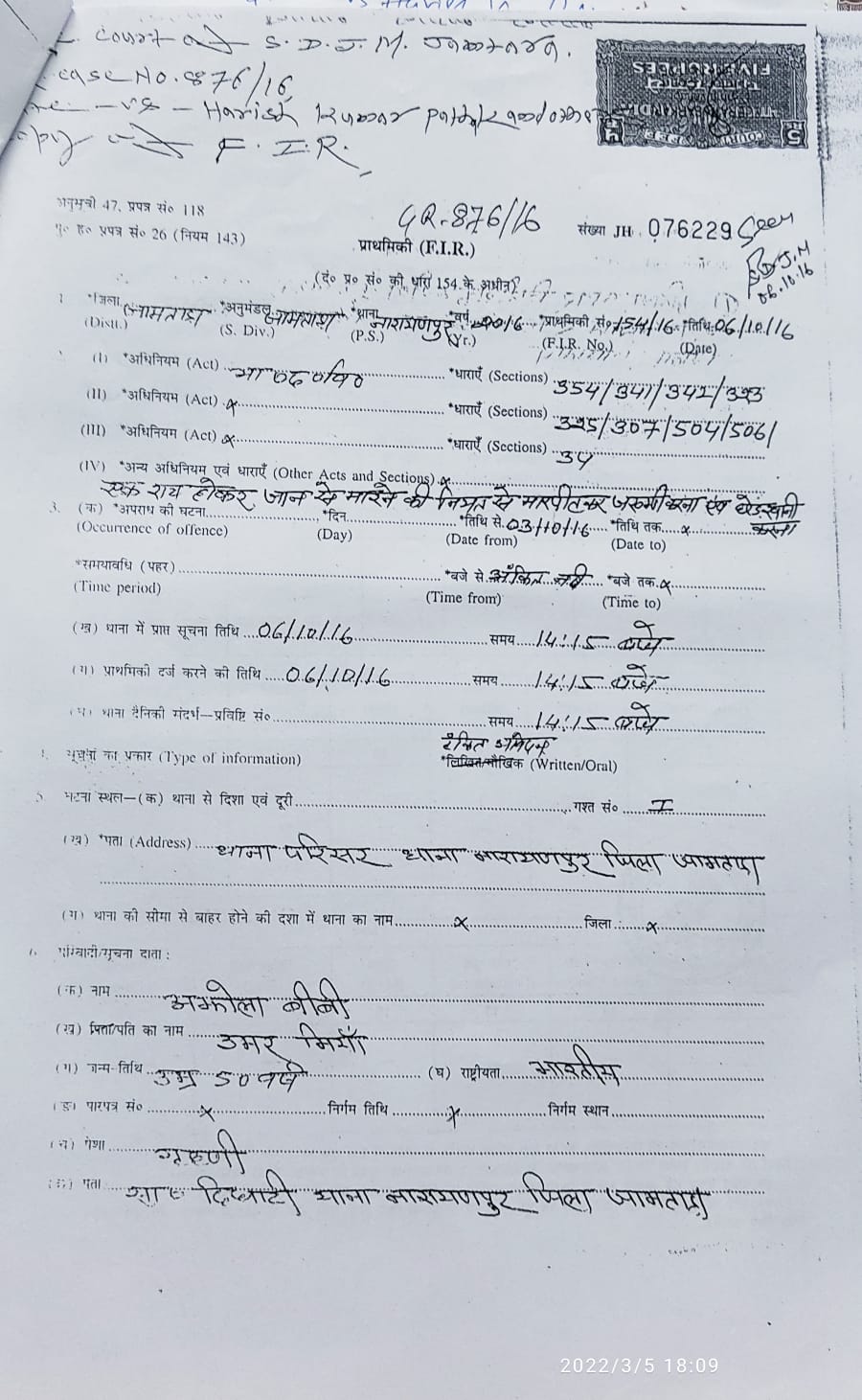

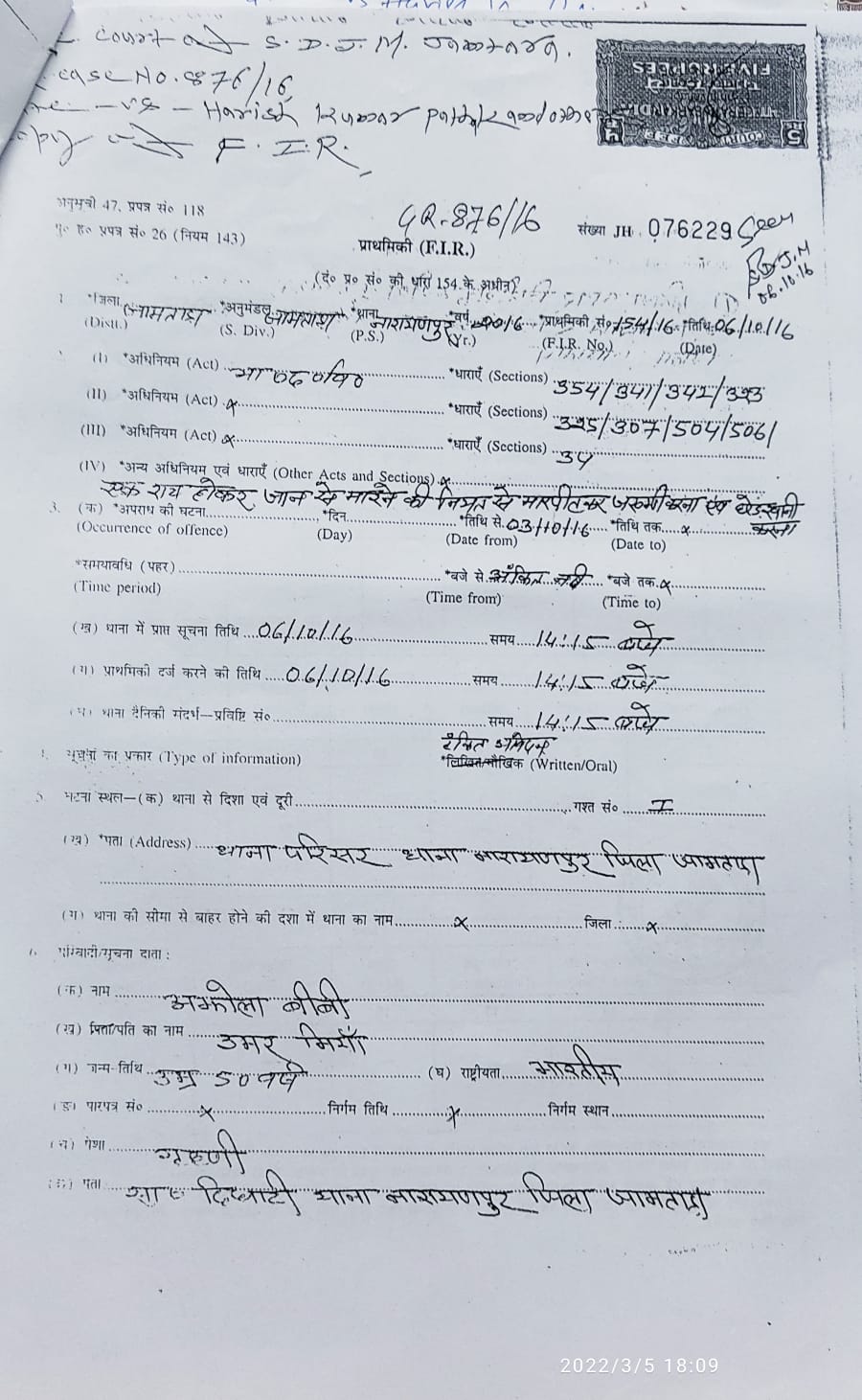

An important factor to keep in mind while considering NCRB data, is its source. NCRB data comes from police stations across India. When a complainant approaches a police station, the Police may turn their complaint into a First Information Report (FIR). All FIRs filed in police stations across the country are collected at the state level and then put together at the national level to produce these statistics. Yet, the NCRB’s processes and methodology are not transparent. Data journalist Rukmini S., in her book Whole Numbers and Half-Truths, notes that India’s crime statistics begin from a point of significant underreporting and that the country’s officially recorded crime rates are lower than the global average, substantially lower than developed countries and even low even by middle income country standards.

Police brutality and torture are ubiquitous, as are the abuse of authority and discrimination against caste and religious minorities in India. These acts of violence, brutality and torture along with intimidating people and extracting confessions are often viewed as integral to policing. A 2016 Human Rights Watch report that probed custodial deaths, arrest procedures, victim’s family accounts and Police impunity found instances where custodial deaths were intentionally misreported as suicides or fatalities due to illness or natural causes.

According to the NCRB, between 2010 and 2015, 591 people died in police custody. Of the 97 custody deaths reported by Indian authorities in 2015, police records list only 6 due to physical assault by the Police; 34 are listed as suicides, 11 as deaths due to illness, 9 as natural deaths and 12 as deaths during hospitalization or treatment. However, in many cases, family members allege that the deaths were the result of torture. An Asian Center for Human Rights (ACHR) report stated that a total of 1,674 custodial deaths, including 1,530 in judicial custody and 144 in police custody, took place between 1 April 2017 and 28 February 2018 in India. This means that on an average there were about five custodial deaths per day in this period. Reports of the National Human Rights Commission (NHRC) compiled by ACHR also indicated that between 2001 and 2011, 1,504 people died in police custody (about 150 per year) and 12,727 people died in judicial custody (1,414 per year). No data are readily available on incidents of torture, although some queries in Parliament have led to an acknowledgment of 855 individuals tortured from 2010 to 2011, which greatly underestimates the scope of the problem.

In the India: Annual Report on Torture 2019, the NHRC recorded a total of 1,723 cases of death in judicial and police custody from January to December 2019. These included 1,606 deaths in judicial custody and 117 in police custody. From 1 April 2020 to 31 March 2022, every state in India, except for three union territories, have reported at least one case of custodial death.

*

Despite strict guidelines, the authorities routinely fail to conduct rigorous investigations and prosecute police officials implicated in torture and ill-treatment of arrested persons. Police investigators often close cases relying solely on the accounts of the implicated officers. Indian Police often bypass Supreme Court rules to prevent custodial abuse set out in the case of D.K. Basu v. West Bengal in 1996. Since incorporated into the amended Code of Criminal Procedure (CrPC), the rules call for the Police to identify themselves clearly when making an arrest; prepare a memo of arrest with the date and time of arrest that is signed by an independent witness and countersigned by the arrested person; ensure that next of kin are informed of the arrest and the place of detention.

A person is kept in police custody when they are arrested by the Police based on a First Information Report (FIR), or on the basis of suspicion. The police station has control over police custody. A person is kept in judicial custody based on the order by a magistrate. The NHRC defines judicial custody as persons in jail under court order which include convicts and undertrials. During judicial custody, the Police are not allowed to interrogate the suspect. However, in some cases where credible evidence is produced, the Courts may allow the Police to interrogate the suspects for which police custody is granted. While in police custody, the suspect is in the police station lockup and during judicial custody the suspect is in jail in the custody of the concerned magistrate. The possible sites of violence may vary based on whether a person is in police or judicial custody, and whether the person is lodged in a police station, prison or jail.

After a suspect is arrested, they are taken to police custody following which they are to be produced before a magistrate. The magistrate then decides if the arrested person is supposed to be sent to judicial custody or back to police custody. The rules require arrested persons to be medically examined after being taken into custody, with the doctor listing any pre-existing injuries while any new injuries will point to police abuse in custody. Another important check on police abuse is the requirement that every arrested person be produced before a magistrate within the first 24 hours, however, under the orders of the magistrate a person may be held up to 15 days in police custody. An IndiaSpend analysis reveals that of the 1,004 deaths in police custody recorded from 2010 to 2019 recorded, 63 percent died within 24 hours of being arrested by the Police (‘Person not remanded’) while 633 persons died before being produced in front of magistrate’s courts, as prescribed by Section 57 of the Code of Criminal Procedure (CrPC), 1973.

The magistrates have a duty to prevent overreach of police powers by inspecting arrest-related documents and ensuring the wellbeing of suspects by directly questioning them. Indian law requires a judicial magistrate to conduct an inquiry into every custodial death, however, in several cases of custodial deaths from 2010-2019, NCRB data show that these enquiries were not ordered. According to government data, in 67 of 97 deaths in custody in 2015, the Police either failed to produce the suspects before a magistrate within 24 hours as required by law or the suspects died within 24 hours of being arrested.

The Police are expected to register an FIR and the death investigated by a police station or an agency other than the one implicated. Every case of custodial death is supposed to be reported by the district magistrates and the superintendents of police to the NHRC within 24 hours as per their guidelines. The Police are also required to report the findings of the magistrate’s inquiry to the NHRC along with the post-mortem . NHRC rules call for the autopsy to be filmed and the autopsy report to be prepared according to a standard form.

According to government data, a judicial inquiry was conducted in only 31 of the 97 custodial deaths reported in 2015. In 26 cases, there was not even an autopsy of the deceased. In some states, an executive magistrate — who belongs to the executive branch of the Government as do the Police and therefore is not independent and is likely to face pressures not to act impartially — conducted the investigation rather than a judicial magistrate. In 2015, the Police registered cases against fellow police officers in only 33 of the 97 custodial deaths.

The Police admit to arresting people and keeping them in custody till a confession is obtained, often employing any methods and techniques to ensure a suspect pleads guilty. In a historic 2006 Supreme Court order, one of the seven binding directives is that every state should have a police complaints authority where citizens can file complaints of misconduct and wrongdoing by the Police. However, few states in India have implemented this directive. Only Andhra Pradesh is fully compliant with this directive, but the compliance only remains on paper, according to a Commonwealth Human Rights Initiative (CHRI) 2020 report on government compliance with the Supreme Court directives.

A few common scenarios where police brutality often result in custodial deaths include: Negligence by the concerned authorities, including safety and medical aid provided to the detainees; torture and misconduct by the authorities; unlawful detention of a person above the stipulated period (The Police may not hold a suspect beyond 24 hours of arrest. Any custody above 24 hours may only be by the order of the magistrate); undue pressure resulting in the person taking their own life to avoid torture from the authorities (Abetment to suicide).

*

Religious minorities, oppressed castes, Adivasis and other marginalized and poor social groups represent the disproportionate majority of victims of custodial deaths in India. This targeting is indicative of institutional bias and structural discrimination. Christophe Jaffrelot highlights such biases within the Police and the judiciary in India in Modi’s India: Hindu Nationalism and the Rise of Ethnic Democracy: the percentage of Muslims awaiting trial in prison is traditionally high; it was 21 percent in 2016, and in the state of Uttar Pradesh the proportion of Muslims undertrial prisoners was double the percentage of the Muslim population in the state. In 2016 and 2017, the NCRB annual report did not give any information regarding the caste and religion of prison inmates. In 2018, new prison statistics were released and they confirmed the overrepresentation of Muslims in jail (18.8 percent), especially in Uttar Pradesh.

The Status of Policing in India Report 2018 by Common Cause and Lokniti – Centre for the Study Developing Societies (CSDS) highlights that 26 percent of Muslim respondents believe that the Indian Police discriminate on the basis of religion; and 54 percent of Muslims are fearful of the Police as opposed to 24 percent Hindus though opinions vary considerably by caste. Apart from bias and systemic discrimination, the underrepresentation of certain social groups within Indian state institutions increases their vulnerability and violence at the hands of the same state institutions such as the Police.

In 2014, while reviewing cases of custodial deaths in Maharashtra, the Bombay High Court asked why the majority of victims of custodial deaths belong to minority communities. In 2019, according to a report by United NGO Campaign Against Torture (UNCAT), almost five custodial deaths occurred daily and around 60 percent of the victims belonged to poor and marginalized communities including Dalits, Adivasis and Muslims. Additionally, data from the annual NHRC reports from 1996-97 to 2017-18 revealed that 71.58 percent of those who died in custody were from poor or marginalized sections of society.

The 2019 Prison Statistics of India 2019 reveal that 21 percent and 11 percent of the incarcerated individuals in India’s prisons belong to the Scheduled Caste (SC) and Scheduled Tribe (ST) communities respectively. According to the Criminal Justice and Police Accountability Project’s (CPAP) report Drunk on Power, the Vimukta communities DNTs (denotified tribes, DNTs ) continue to be regarded as hereditary criminals – as under the colonial Criminal Tribes Act, 1871, repealed in 1952 – and the police disproportionately accuses, surveils and regulates individuals, especially women, belonging to this community.

Over the years, fact-finding reports produced by People’s Union for Democratic Rights (PUDR) have also pointed out that the majority of the victims of custodial deaths are from the marginalized socio-economic sections of society.

*

While we initially reviewed thirty-seven cases of custodial deaths during the years 2015 and 2016, based on news reports and other sources, we eventually decided to narrow down on fifteen cases to establish patterns of police brutality and impunity by tracking the details of the cases. These fifteen cases of reported custodial deaths are from various locations across the country: one case from Jharkhand, seven cases from Tamil Nadu, five cases from Telangana, and two from West Bengal.

On 3 October 2016, Minhaj Ansari, a 22 year old owner of a photocopy/mobile phone shop, and two of his friends were arrested from their village Dighari in Jamtara district, in the state of Jharkhand. Ansari had allegedly posted a photograph of himself with a calf on a WhatsApp group the previous day, followed by another of him posing with beef. The participants of the group found the images “obscene” and complained to the Police. After two days in police custody, he was finally taken to a hospital in Ranchi to be treated for injuries where he was eventually declared dead on 9 October 2016.

P.Ramkumar, a 24 year old, belonging to the Pallar caste (classified as Scheduled Caste in the state of Tamil Nadu) and a resident of Meenakshipuram village in Tenkasi, Tirunelveli, Tamil Nadu, was arrested by the Chennai Police on 2 July 2016. He was arrested in connection with the alleged murder on 24 June 2016 of Swathi, a 24-year-old Brahmin woman who was working as an IT professional. He died on 18 September 2016 in judicial custody in a high-security prison.

Shameel Basha, a 26-year-old, was picked up by the Police in connection with a missing person’s case of a former-colleague. He was previously working at a leather company in Ambur, Tamil Nadu. He was kept in police custody at Pallikonda Police station from 15 to 18 June 2015, and he died in Rajiv Gandhi Government General Hospital, Chennai, on 26 June 2015, following health complications which he reportedly developed while in police custody.

Meenkulambu Karthik, 22, a resident of Chetpet who belonged to a Scheduled Caste community, was picked up by the Police on 19 September 2016 for robbing, with three others, a female information technology professional, in Chennai, Tamil Nadu, and snatching her chain. He died on 21 September 2016, when he was rushed to the hospital as he complained of breathlessness. Hospital authorities said that he was brought dead.

51-year-old Kuppuswamy was a small shop owner who was arrested for illegal liquor sale. He was lodged in Madurai prison (Tamil Nadu) under judicial custody. He died on 15 August 2016 the same day he was arrested.

Mohan, a Sri Lankan national in his early forties, was picked up by the Central Crime Branch of the Tamil Nadu Police, in an alleged fake passport racket. He died a few hours after he was picked up and taken for questioning on 3 September 2015.

Gokulakannan, 22, was a contract laborer who was picked up by six plainclothes policemen from his home in the context of a murder. He was picked up around midnight and was rushed to the hospital in Salem, Tamil Nadu by the Police, where he was declared “brought dead”. He died on 6 June 2015.

Bujji, 19 years old, from Bangalore, Karnataka, was detained for his role in the killing of a police constable. He died a few hours after he was taken into police custody, in Tamil Nadu, on 15 June 2016. According to the Police he died as a result of cardiac arrest while in police custody

On 21 March 2015, a 25-year-old Muslim daily wager, Sheikh Hyder, was arrested for an alleged bicycle theft and died on the same day in the police station in the state of Telangana.

Viqaruddin Ahmed, a 35-year-old, was a suspect in the Mecca Masjid bombing in Hyderabad in which two policemen died. The Police killed Ahmed and four others in an “encounter” near Alair, in the Nalgonda district of Telangana on 7 April 2015. Ahmed along with the suspects in the case were en route to the Hyderabad Court from Warangal Jail and were escorted by 17 police personnel.

G.Bonappa was a 35 year old resident of Gandhi Nagar colony in Hyderabad, Telangana, and a contract employee with the state electricity department. The Police claim that Bonappa was inebriated during the Bonalu festival and was dancing with a procession. They claim that they picked him up in the evening on 2 August 2015 after he got into a fight with a home guard. He died the following day on 3 August 2015.

Padma, a 39-year-old woman, was called in for questioning to the Asifnagar police station in Hyderabad, Telangana, in connection with a theft case. She was called in for questioning on 21 August 2015, when she was sick, and called in again the next day on 22 August, which is when she collapsed and died according to the Police.

Lakshman, a 35 year old man, was an accused in a murder case and was arrested by the Pulkal Police in Medak district of Telangana. Lakshman owed Rs 450,000 to a woman and when she demanded the amount back, he allegedly killed her in 2014 in Medak before fleeing to Mumbai. A police officer said: “While he was in the sub inspector’s room in the police station, he removed his shirt and attempted to hang himself from window grills at around 4 AM.” A constable noticed him and took him to a nearby hospital from where he was referred to a government hospital in Hyderabad on 12 March 2015. Lakshman died on the way to the hospital.

Obaidur Rahman, a 52-year-old farmer in Sonakul village in Malda district in the state of West Bengal, was wanted by the Police in a criminal case arising out of a land dispute with his neighbor. Rahman died in police custody in Malda within 24 hours of his arrest, on 21 January 2015.

Bhushan Deshmukh, a 28-year-old man, worked at a jewelry shop in a neighborhood of north Kolkata, West Bengal, and hailed from Satara in Maharashtra. He was arrested under the Arms Act for possession of illegal weapons on 20 September 2015 in the city of Kolkata. Burtolla police claimed he died of diarrhea, but a post-mortem report revealed multiple injuries all over the body, suggesting that he was beaten up by more than one individual.

All the victims, except one from Telangana, are men, and the majority of them are in the age group of 20 to 35 years old. The reason that women are not usually victims of custodial deaths, is that women have further restrictions on their mobility and are less likely to roam in public places. Further, it’s likely that the Police molded by and operating in a patriarchal society is more lenient towards the minor transgressions by women, according to CPAP’s report on pandemic policing.

Information for the cases were gathered from English news reports and publicly available information online, documents were obtained from various sources: the NHRC website; e-courts portal for district courts; High Court and Supreme Court website; Indian Kanoon website, SCC (Supreme Court Cases) Online; and the Manupatra website. Fact finding reports and other evidence were obtained from human rights organizations and from court documents.

National Crime Records Bureau: Crime in India 2015-2016[1]

| Year | Deaths in Police custody/lockup | Number of cases registered | Police personnel arrested | Total number of deaths | Total number of cases registered | Total number of police personnel arrested/chargesheeted | |

| 2016 | Persons not on remand | 60 (death or disappearance) | 19 | 10 (chargesheeted) | 92 | 25 | 24 (chargesheeted) |

| Persons on remand | 32 | 6 | 14 (chargesheeted) | ||||

| 2015 | Persons not on remand | 67 (death or disappearance) | 24 | 24 (chargesheeted) | 97 | 33 | 28 (chargesheeted) |

| Persons on remand | 30 (death or disappearance) | 9 | 4 (chargesheeted) |

While the NCRB’s Crime in India reports list the number of custodial deaths at 97 and 92 respectively for 2015 and 2016, the NHRC provides numbers that are vastly different for the same time period. For the period from 1 April 2015 to 31 March 2016, the NHRC has registered intimations on cases of custodial deaths and rapes in judicial and police custody at a total of 1,822 cases. The NCRB provides statistics to the number of custodial deaths in India and the NHRC lists, through its annual reports, the number of complaints it has received of custodial deaths along with case details of a few illustrative cases. However, the main contributors to gathering facts in cases of custodial deaths and presenting information from the victims’ perspective and fighting for their justice are grassroots human rights and civil liberties organizations in India.

In this analysis of judicial and administrative accountability in cases of custodial death in India, we look at 15 cases of custodial deaths (police and judicial custody) in India from 2015-2016. While the first essay set the context and introduced the cases selected for this project, the following essays will discuss the official reasons for custodial deaths provided by the Police, the types of accountabilities that have taken place in these cases, the complicity of state and non-state institutions, followed by a concluding essay that brings all our findings together and discusses limitations and scope for further research.

**************************

[1] These reports include deaths in police custody of persons in remand and those not in remand. Along with this, reasons for custodial death, cases registered against police personnel, cases registered against state police personnel for human rights violations, police personnel acquitted, chargesheeted, arrested, discharged are included. Source: NCRB Crime in India (2014-2018)

Related Posts

“In our great democracy, peacekeepers are given a free rein and are a law unto themselves.”

T.J. Joseph, A Thousand Cuts.

On 19 June 2020, during the COVID-19 pandemic in India, 59 year old Jeyaraj and his 31-year -old son Bennix were picked up by the Tamil Nadu Police from Sathankulam, Thoothukudi district in Tamil Nadu. The Police claim that the duo kept their mobile accessories shop open beyond permissible hours and violated the Indian government’s COVID-19 lockdown rules. They were tortured and sexually assaulted in police custody, which resulted in their deaths, or in other words, in institutional murder. The term custody refers to apprehending someone for protective care.

In November 2021, in the state of Uttar Pradesh, 22-year-old Altaf died in police custody. According to the Police, he asked to go to the washroom while he was being questioned and hung himself from the water pipeline using the string of the hood of his jacket. According to the Union government, Uttar Pradesh reported the highest number of custodial deaths among all states and Union Territories with 451 custodial deaths in 2020-2021, and 501 in 2021-2022.

In the last week of July and the first week of August in 2022, four Muslim men – Abdul Rajjak, Jiyaul Laskar, Akbar Khan and Saidul Munsi were reported to have died in judicial custody at the Baruipur Central Correctional Home, South 24 Parganas district, West Bengal. All the four men had been picked up by the West Bengal police in separate cases in the last week of July 2022. West Bengal registered the second highest number of custodial deaths during 2020-2021 (185 in 2020 and 257 in 2021).

Instances of custodial violence and torture abound the criminal justice landscape in India. According to political scientist and legal scholar Jinee Lokaneeta, the Police in postcolonial India have often been accused of using torture or third-degree interrogation in both routine and exceptional criminal cases and have been deemed responsible for hundreds of custodial deaths each year. News articles, reports by human rights organizations, journalistic investigations and data shared by the Government of India, all substantiate this fact. Yet, such crimes have not been addressed, proposed reforms have not been implemented and custodial violence and torture are considered to be a routine part of the Indian criminal justice system.

How and why has torture become a routine part of routine police procedure in liberal democracies? Anthropologist Veena Das addresses this question in her article describing Innocent Prisoners (2021), a book by Abdul Wahid Sheikh that details the wrongful incarceration of innocent prisoners in India. For Das, to tackle the disorders of democracy that challenge classical theories of state formation and governance, it is crucial to engage with scholarly works by journalists, schoolteachers and lawyers. While these sources are not commonly considered by academic theory, they provide insights into the working of the State machinery and Police biases vis-a-vis torture in India. Also, in Slum Acts (2022), Das asks: What are the limits of permissible and non-permissible forms or acts of violence? How do we distinguish between the ‘barbaric’ and ‘civilized’ forms of violence?

When we shift the focus to the context of custodial deaths, how does Police torture become ‘necessary’ and therefore ‘civilized’ within our conceptions of democracies? Scholar Upendra Baxi argues that torture is institutionalized in India and custodial violence and torture are an integral part of police operations. Lawyer Nitya Ramakrishnan in In Custody: Law, Impunity and Prisoner Abuse in South Asia notes that in Indian society the concepts of justice and torture are inextricable: “torture becomes a fantasy of justice.”

Why are custodial deaths – an urgent issue – not given enough importance? Why are strict measures not taken? To understand questions of accountability and impunity in the context of custodial deaths in India, we look at a few cases that have received limited public attention. Most of the victims of custodial deaths belong to religious minorities, Scheduled Castes (SC) and Other Backward Castes communities. They come from various parts of the country, from underprivileged and oppressed backgrounds and they all died in 2015 and 2016, in either police or judicial custody. They are: Minhaj Ansari, P. Ramkumar, Shameel Basha, Meenkulambu Karthik, Kuppuswamy, Mohan, N. Gokulakannan, Bujji, Sheikh Hyder, Viqaruddin Ahmed, G.Bonappa, N. Padma, T. Lakshman, Obaidur Rahman and Bhushan Deshmukh.

We look at these cases to understand the nature of ongoing impunity enjoyed by various law enforcement agencies and the complicity of both state and non-state institutions. We specifically look at cases from 2015 and 2016 since enough time has passed to analyze whether any measures of accountability have been taken, keeping in mind the pace of the Indian criminal justice system.

Ample evidence points to the Police as perpetrators of state violence when denying or taking away a person’s right to life and personal liberty. The Police in India are in charge of crime control, investigations as well as law and order. Policing is subject to Article 246 of the Indian Constitution and each Indian state can set its own rules for police recruitment and governance. Despite states’ autonomy to organize their policing, police bodies remain modeled on the Police Act of 1861, promulgated by the British. While states have different statues, there are features that are common to all of them. Most police statutes recognize dereliction of duty as of service misconduct and invite disciplinary action against officers in whose custody prisoners have died. Officers who are charged with a prima facie case of custodial rape invite disciplinary action as per most police statutes. Custodial deaths, which occur when a person is either in judicial or police custody, are a common result of torture, which is a part of routine police procedure in India.

*

While various legal frameworks and measures have been proposed over the last few decades to act on torture by public officials, they have not been implemented yet.

Since 14 October 1997, India has been a signatory to the United Nation’s Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment but has yet to ratify this crucial international human rights instrument. In April 2010, the The Prevention of Torture Bill, 2010 was introduced in India’s lower house of Parliament, the Lok Sabha, passed in the house and referred to the upper house of Parliament. The select committee constituted to prepare a report on the bill and to help ratify its commitment to the Convention against Torture presented its findings in December 2010. In October 2017, the Law Commission of India published their report titled Implementation of ‘United Nations Convention against Torture and other Cruel, Inhuman and Degrading Treatment or Punishment’ through Legislation. This report was then introduced in the Rajya Sabha as a private member bill on 15 December 2017 as the Prevention of Torture Bill, 2017 , but was not enacted. The same bill was introduced again in the Lok Sabha on 9 February 2018 as a private member bill, but since then both bills have lapsed. A modified bill called the Prevention of Torture and Atrocities (By Public Servants) Bill, 2019 was introduced in the Lok Sabha in December 2021 and is pending and no legislation has been passed to define, condemn and take action against torture by public officials in India.

*

Despite existing legal frameworks that guarantee and protect the rights of prisoners, custodial deaths and torture often go unpunished in India. According to the Indian National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB – India’s only official statistics on crime), in 2017 about 100 people died in police custody, but there were no convictions. In 62 cases of these custodial deaths, 33 police personnel were arrested, 27 were charge-sheeted, four were acquitted or discharged and none were convicted. In addition, the NCRB also recorded “56 cases against police personnel for human rights violations. In total, 57 police officers were arrested, 48 charge-sheeted, and only three convicted.” Numbers show that in the 18 years between 2001 and 2018, only 810 cases were registered, 334 charge-sheeted and only 26 police personnel were convicted. This abysmally low rate of conviction and accountability among the Police exists in a democracy where citizens are guaranteed the right to life and personal liberty.

An important factor to keep in mind while considering NCRB data, is its source. NCRB data comes from police stations across India. When a complainant approaches a police station, the Police may turn their complaint into a First Information Report (FIR). All FIRs filed in police stations across the country are collected at the state level and then put together at the national level to produce these statistics. Yet, the NCRB’s processes and methodology are not transparent. Data journalist Rukmini S., in her book Whole Numbers and Half-Truths, notes that India’s crime statistics begin from a point of significant underreporting and that the country’s officially recorded crime rates are lower than the global average, substantially lower than developed countries and even low even by middle income country standards.

Police brutality and torture are ubiquitous, as are the abuse of authority and discrimination against caste and religious minorities in India. These acts of violence, brutality and torture along with intimidating people and extracting confessions are often viewed as integral to policing. A 2016 Human Rights Watch report that probed custodial deaths, arrest procedures, victim’s family accounts and Police impunity found instances where custodial deaths were intentionally misreported as suicides or fatalities due to illness or natural causes.

According to the NCRB, between 2010 and 2015, 591 people died in police custody. Of the 97 custody deaths reported by Indian authorities in 2015, police records list only 6 due to physical assault by the Police; 34 are listed as suicides, 11 as deaths due to illness, 9 as natural deaths and 12 as deaths during hospitalization or treatment. However, in many cases, family members allege that the deaths were the result of torture. An Asian Center for Human Rights (ACHR) report stated that a total of 1,674 custodial deaths, including 1,530 in judicial custody and 144 in police custody, took place between 1 April 2017 and 28 February 2018 in India. This means that on an average there were about five custodial deaths per day in this period. Reports of the National Human Rights Commission (NHRC) compiled by ACHR also indicated that between 2001 and 2011, 1,504 people died in police custody (about 150 per year) and 12,727 people died in judicial custody (1,414 per year). No data are readily available on incidents of torture, although some queries in Parliament have led to an acknowledgment of 855 individuals tortured from 2010 to 2011, which greatly underestimates the scope of the problem.

In the India: Annual Report on Torture 2019, the NHRC recorded a total of 1,723 cases of death in judicial and police custody from January to December 2019. These included 1,606 deaths in judicial custody and 117 in police custody. From 1 April 2020 to 31 March 2022, every state in India, except for three union territories, have reported at least one case of custodial death.

*

Despite strict guidelines, the authorities routinely fail to conduct rigorous investigations and prosecute police officials implicated in torture and ill-treatment of arrested persons. Police investigators often close cases relying solely on the accounts of the implicated officers. Indian Police often bypass Supreme Court rules to prevent custodial abuse set out in the case of D.K. Basu v. West Bengal in 1996. Since incorporated into the amended Code of Criminal Procedure (CrPC), the rules call for the Police to identify themselves clearly when making an arrest; prepare a memo of arrest with the date and time of arrest that is signed by an independent witness and countersigned by the arrested person; ensure that next of kin are informed of the arrest and the place of detention.

A person is kept in police custody when they are arrested by the Police based on a First Information Report (FIR), or on the basis of suspicion. The police station has control over police custody. A person is kept in judicial custody based on the order by a magistrate. The NHRC defines judicial custody as persons in jail under court order which include convicts and undertrials. During judicial custody, the Police are not allowed to interrogate the suspect. However, in some cases where credible evidence is produced, the Courts may allow the Police to interrogate the suspects for which police custody is granted. While in police custody, the suspect is in the police station lockup and during judicial custody the suspect is in jail in the custody of the concerned magistrate. The possible sites of violence may vary based on whether a person is in police or judicial custody, and whether the person is lodged in a police station, prison or jail.

After a suspect is arrested, they are taken to police custody following which they are to be produced before a magistrate. The magistrate then decides if the arrested person is supposed to be sent to judicial custody or back to police custody. The rules require arrested persons to be medically examined after being taken into custody, with the doctor listing any pre-existing injuries while any new injuries will point to police abuse in custody. Another important check on police abuse is the requirement that every arrested person be produced before a magistrate within the first 24 hours, however, under the orders of the magistrate a person may be held up to 15 days in police custody. An IndiaSpend analysis reveals that of the 1,004 deaths in police custody recorded from 2010 to 2019 recorded, 63 percent died within 24 hours of being arrested by the Police (‘Person not remanded’) while 633 persons died before being produced in front of magistrate’s courts, as prescribed by Section 57 of the Code of Criminal Procedure (CrPC), 1973.

The magistrates have a duty to prevent overreach of police powers by inspecting arrest-related documents and ensuring the wellbeing of suspects by directly questioning them. Indian law requires a judicial magistrate to conduct an inquiry into every custodial death, however, in several cases of custodial deaths from 2010-2019, NCRB data show that these enquiries were not ordered. According to government data, in 67 of 97 deaths in custody in 2015, the Police either failed to produce the suspects before a magistrate within 24 hours as required by law or the suspects died within 24 hours of being arrested.

The Police are expected to register an FIR and the death investigated by a police station or an agency other than the one implicated. Every case of custodial death is supposed to be reported by the district magistrates and the superintendents of police to the NHRC within 24 hours as per their guidelines. The Police are also required to report the findings of the magistrate’s inquiry to the NHRC along with the post-mortem . NHRC rules call for the autopsy to be filmed and the autopsy report to be prepared according to a standard form.

According to government data, a judicial inquiry was conducted in only 31 of the 97 custodial deaths reported in 2015. In 26 cases, there was not even an autopsy of the deceased. In some states, an executive magistrate — who belongs to the executive branch of the Government as do the Police and therefore is not independent and is likely to face pressures not to act impartially — conducted the investigation rather than a judicial magistrate. In 2015, the Police registered cases against fellow police officers in only 33 of the 97 custodial deaths.

The Police admit to arresting people and keeping them in custody till a confession is obtained, often employing any methods and techniques to ensure a suspect pleads guilty. In a historic 2006 Supreme Court order, one of the seven binding directives is that every state should have a police complaints authority where citizens can file complaints of misconduct and wrongdoing by the Police. However, few states in India have implemented this directive. Only Andhra Pradesh is fully compliant with this directive, but the compliance only remains on paper, according to a Commonwealth Human Rights Initiative (CHRI) 2020 report on government compliance with the Supreme Court directives.

A few common scenarios where police brutality often result in custodial deaths include: Negligence by the concerned authorities, including safety and medical aid provided to the detainees; torture and misconduct by the authorities; unlawful detention of a person above the stipulated period (The Police may not hold a suspect beyond 24 hours of arrest. Any custody above 24 hours may only be by the order of the magistrate); undue pressure resulting in the person taking their own life to avoid torture from the authorities (Abetment to suicide).

*

Religious minorities, oppressed castes, Adivasis and other marginalized and poor social groups represent the disproportionate majority of victims of custodial deaths in India. This targeting is indicative of institutional bias and structural discrimination. Christophe Jaffrelot highlights such biases within the Police and the judiciary in India in Modi’s India: Hindu Nationalism and the Rise of Ethnic Democracy: the percentage of Muslims awaiting trial in prison is traditionally high; it was 21 percent in 2016, and in the state of Uttar Pradesh the proportion of Muslims undertrial prisoners was double the percentage of the Muslim population in the state. In 2016 and 2017, the NCRB annual report did not give any information regarding the caste and religion of prison inmates. In 2018, new prison statistics were released and they confirmed the overrepresentation of Muslims in jail (18.8 percent), especially in Uttar Pradesh.

The Status of Policing in India Report 2018 by Common Cause and Lokniti – Centre for the Study Developing Societies (CSDS) highlights that 26 percent of Muslim respondents believe that the Indian Police discriminate on the basis of religion; and 54 percent of Muslims are fearful of the Police as opposed to 24 percent Hindus though opinions vary considerably by caste. Apart from bias and systemic discrimination, the underrepresentation of certain social groups within Indian state institutions increases their vulnerability and violence at the hands of the same state institutions such as the Police.

In 2014, while reviewing cases of custodial deaths in Maharashtra, the Bombay High Court asked why the majority of victims of custodial deaths belong to minority communities. In 2019, according to a report by United NGO Campaign Against Torture (UNCAT), almost five custodial deaths occurred daily and around 60 percent of the victims belonged to poor and marginalized communities including Dalits, Adivasis and Muslims. Additionally, data from the annual NHRC reports from 1996-97 to 2017-18 revealed that 71.58 percent of those who died in custody were from poor or marginalized sections of society.

The 2019 Prison Statistics of India 2019 reveal that 21 percent and 11 percent of the incarcerated individuals in India’s prisons belong to the Scheduled Caste (SC) and Scheduled Tribe (ST) communities respectively. According to the Criminal Justice and Police Accountability Project’s (CPAP) report Drunk on Power, the Vimukta communities DNTs (denotified tribes, DNTs ) continue to be regarded as hereditary criminals – as under the colonial Criminal Tribes Act, 1871, repealed in 1952 – and the police disproportionately accuses, surveils and regulates individuals, especially women, belonging to this community.

Over the years, fact-finding reports produced by People’s Union for Democratic Rights (PUDR) have also pointed out that the majority of the victims of custodial deaths are from the marginalized socio-economic sections of society.

*

While we initially reviewed thirty-seven cases of custodial deaths during the years 2015 and 2016, based on news reports and other sources, we eventually decided to narrow down on fifteen cases to establish patterns of police brutality and impunity by tracking the details of the cases. These fifteen cases of reported custodial deaths are from various locations across the country: one case from Jharkhand, seven cases from Tamil Nadu, five cases from Telangana, and two from West Bengal.

On 3 October 2016, Minhaj Ansari, a 22 year old owner of a photocopy/mobile phone shop, and two of his friends were arrested from their village Dighari in Jamtara district, in the state of Jharkhand. Ansari had allegedly posted a photograph of himself with a calf on a WhatsApp group the previous day, followed by another of him posing with beef. The participants of the group found the images “obscene” and complained to the Police. After two days in police custody, he was finally taken to a hospital in Ranchi to be treated for injuries where he was eventually declared dead on 9 October 2016.

P.Ramkumar, a 24 year old, belonging to the Pallar caste (classified as Scheduled Caste in the state of Tamil Nadu) and a resident of Meenakshipuram village in Tenkasi, Tirunelveli, Tamil Nadu, was arrested by the Chennai Police on 2 July 2016. He was arrested in connection with the alleged murder on 24 June 2016 of Swathi, a 24-year-old Brahmin woman who was working as an IT professional. He died on 18 September 2016 in judicial custody in a high-security prison.

Shameel Basha, a 26-year-old, was picked up by the Police in connection with a missing person’s case of a former-colleague. He was previously working at a leather company in Ambur, Tamil Nadu. He was kept in police custody at Pallikonda Police station from 15 to 18 June 2015, and he died in Rajiv Gandhi Government General Hospital, Chennai, on 26 June 2015, following health complications which he reportedly developed while in police custody.

Meenkulambu Karthik, 22, a resident of Chetpet who belonged to a Scheduled Caste community, was picked up by the Police on 19 September 2016 for robbing, with three others, a female information technology professional, in Chennai, Tamil Nadu, and snatching her chain. He died on 21 September 2016, when he was rushed to the hospital as he complained of breathlessness. Hospital authorities said that he was brought dead.

51-year-old Kuppuswamy was a small shop owner who was arrested for illegal liquor sale. He was lodged in Madurai prison (Tamil Nadu) under judicial custody. He died on 15 August 2016 the same day he was arrested.

Mohan, a Sri Lankan national in his early forties, was picked up by the Central Crime Branch of the Tamil Nadu Police, in an alleged fake passport racket. He died a few hours after he was picked up and taken for questioning on 3 September 2015.

Gokulakannan, 22, was a contract laborer who was picked up by six plainclothes policemen from his home in the context of a murder. He was picked up around midnight and was rushed to the hospital in Salem, Tamil Nadu by the Police, where he was declared “brought dead”. He died on 6 June 2015.

Bujji, 19 years old, from Bangalore, Karnataka, was detained for his role in the killing of a police constable. He died a few hours after he was taken into police custody, in Tamil Nadu, on 15 June 2016. According to the Police he died as a result of cardiac arrest while in police custody

On 21 March 2015, a 25-year-old Muslim daily wager, Sheikh Hyder, was arrested for an alleged bicycle theft and died on the same day in the police station in the state of Telangana.

Viqaruddin Ahmed, a 35-year-old, was a suspect in the Mecca Masjid bombing in Hyderabad in which two policemen died. The Police killed Ahmed and four others in an “encounter” near Alair, in the Nalgonda district of Telangana on 7 April 2015. Ahmed along with the suspects in the case were en route to the Hyderabad Court from Warangal Jail and were escorted by 17 police personnel.

G.Bonappa was a 35 year old resident of Gandhi Nagar colony in Hyderabad, Telangana, and a contract employee with the state electricity department. The Police claim that Bonappa was inebriated during the Bonalu festival and was dancing with a procession. They claim that they picked him up in the evening on 2 August 2015 after he got into a fight with a home guard. He died the following day on 3 August 2015.

Padma, a 39-year-old woman, was called in for questioning to the Asifnagar police station in Hyderabad, Telangana, in connection with a theft case. She was called in for questioning on 21 August 2015, when she was sick, and called in again the next day on 22 August, which is when she collapsed and died according to the Police.

Lakshman, a 35 year old man, was an accused in a murder case and was arrested by the Pulkal Police in Medak district of Telangana. Lakshman owed Rs 450,000 to a woman and when she demanded the amount back, he allegedly killed her in 2014 in Medak before fleeing to Mumbai. A police officer said: “While he was in the sub inspector’s room in the police station, he removed his shirt and attempted to hang himself from window grills at around 4 AM.” A constable noticed him and took him to a nearby hospital from where he was referred to a government hospital in Hyderabad on 12 March 2015. Lakshman died on the way to the hospital.

Obaidur Rahman, a 52-year-old farmer in Sonakul village in Malda district in the state of West Bengal, was wanted by the Police in a criminal case arising out of a land dispute with his neighbor. Rahman died in police custody in Malda within 24 hours of his arrest, on 21 January 2015.

Bhushan Deshmukh, a 28-year-old man, worked at a jewelry shop in a neighborhood of north Kolkata, West Bengal, and hailed from Satara in Maharashtra. He was arrested under the Arms Act for possession of illegal weapons on 20 September 2015 in the city of Kolkata. Burtolla police claimed he died of diarrhea, but a post-mortem report revealed multiple injuries all over the body, suggesting that he was beaten up by more than one individual.

All the victims, except one from Telangana, are men, and the majority of them are in the age group of 20 to 35 years old. The reason that women are not usually victims of custodial deaths, is that women have further restrictions on their mobility and are less likely to roam in public places. Further, it’s likely that the Police molded by and operating in a patriarchal society is more lenient towards the minor transgressions by women, according to CPAP’s report on pandemic policing.

Information for the cases were gathered from English news reports and publicly available information online, documents were obtained from various sources: the NHRC website; e-courts portal for district courts; High Court and Supreme Court website; Indian Kanoon website, SCC (Supreme Court Cases) Online; and the Manupatra website. Fact finding reports and other evidence were obtained from human rights organizations and from court documents.

National Crime Records Bureau: Crime in India 2015-2016[1]

| Year | Deaths in Police custody/lockup | Number of cases registered | Police personnel arrested | Total number of deaths | Total number of cases registered | Total number of police personnel arrested/chargesheeted | |

| 2016 | Persons not on remand | 60 (death or disappearance) | 19 | 10 (chargesheeted) | 92 | 25 | 24 (chargesheeted) |

| Persons on remand | 32 | 6 | 14 (chargesheeted) | ||||

| 2015 | Persons not on remand | 67 (death or disappearance) | 24 | 24 (chargesheeted) | 97 | 33 | 28 (chargesheeted) |

| Persons on remand | 30 (death or disappearance) | 9 | 4 (chargesheeted) |

While the NCRB’s Crime in India reports list the number of custodial deaths at 97 and 92 respectively for 2015 and 2016, the NHRC provides numbers that are vastly different for the same time period. For the period from 1 April 2015 to 31 March 2016, the NHRC has registered intimations on cases of custodial deaths and rapes in judicial and police custody at a total of 1,822 cases. The NCRB provides statistics to the number of custodial deaths in India and the NHRC lists, through its annual reports, the number of complaints it has received of custodial deaths along with case details of a few illustrative cases. However, the main contributors to gathering facts in cases of custodial deaths and presenting information from the victims’ perspective and fighting for their justice are grassroots human rights and civil liberties organizations in India.

In this analysis of judicial and administrative accountability in cases of custodial death in India, we look at 15 cases of custodial deaths (police and judicial custody) in India from 2015-2016. While the first essay set the context and introduced the cases selected for this project, the following essays will discuss the official reasons for custodial deaths provided by the Police, the types of accountabilities that have taken place in these cases, the complicity of state and non-state institutions, followed by a concluding essay that brings all our findings together and discusses limitations and scope for further research.

**************************

[1] These reports include deaths in police custody of persons in remand and those not in remand. Along with this, reasons for custodial death, cases registered against police personnel, cases registered against state police personnel for human rights violations, police personnel acquitted, chargesheeted, arrested, discharged are included. Source: NCRB Crime in India (2014-2018)

SUPPORT US

We like bringing the stories that don’t get told to you. For that, we need your support. However small, we would appreciate it.