Woman! Life! Freedom!: A Counter-Archive of Defiance and Survival in Iran

In 2022, the echo of the slogan, “Jin, Jiyan, Azadi” (“Woman, Life, Freedom”), reverberated far beyond Iran’s borders. The images were unforgettable: young Iranian women setting their veils on fire, cutting their hair in public defiance, dancing bareheaded in the streets. The courage was raw and collective. But what lies beneath this spectacle of resistance? What is the anatomy of such an uprising, and what silences and struggles precede the moment when revolt bursts onto the streets?

In her 2025 book Woman! Life! Freedom! Echoes of a Revolutionary Uprising in Iran, political anthropologist and feminist Chowra Makaremi takes us to the heart of feminist resistance in Iran. She does not offer simple explanations. Instead, she weaves together personal memory, historical excavation, and ethnographic insight to trace the trajectory of Iranian society that led to this revolutionary moment. She asks: What does it mean to resist in a state that kills, silences, and forgets? How do women carry intergenerational trauma while also holding the charge of liberation?

What emerges in Woman! Life! Freedom! is a long and tangled history of power and resistance, refracted not only through political theory or scholarly detachment, but also through the intimate and embodied lens of Makaremi herself—an anthropologist, a woman in exile, and the daughter of a revolutionary, her mother, Fatemeh Zarei, and aunt having been jailed and executed by the state in the 1980s.

Her mother becomes a spectral presence throughout the text, as does her maternal grandfather’s 2011 memoir Aziz’s Notebook: At the Heart of the Iranian Revolution, which she discovered and translated decades after it was written at the height of state repression during Khomeini’s regime in Iran.

Translated from the French by Maya Judd, Makaremi’s book resists the sanitized language of conventional political analysis. She does not shy away from this proximity to violence; instead, she wields it as a feminist method, positioning memory as resistance, grief as an archive, and subjectivity as a valid and urgent site of knowledge.

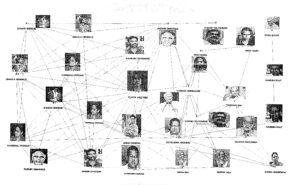

Makaremi’s commitment to counter-archives—those informal, fugitive, and affect-laden records of dissent—refuses to separate the emotional from the political. Through testimonies, chants, photographs, social media videos, and her own recollections, she constructs a living, breathing archive of rebellion. This is not just a documentation of revolt, but an invocation: a call to remember, to mourn, and to rise.

The Long Wound of Authoritarianism

On 16 September 2022, 22-year-old Kurdish-Iranian woman, Jina (Mahsa) Amini, died after being arrested, taken to the “re-education centre” run by the morality police under Iran’s hijab laws, and beaten in custody. Amini’s death resonated with women in Iran not just as an incident of state violence, but as a mirror of their own precarity and erasure. “Identifying with Jina’s fate,” Makaremi writes, “made her death a political and emotional ordeal for Iranian women within and outside the country and for many women around the world.” In Woman! Life! Freedom! Makaremi traces the anatomy of this fire, showing us that revolt is rarely sudden—it is built, layer by layer, by lives lived under siege.

The Gasht-e Ershad (“morality police”), established in 2005, is not a marginal force but a central technology of the Islamic Republic’s gendered statecraft: a roving apparatus authorised to surveil, detain, and publicly punish women for violating compulsory hijab laws or perceived moral codes. Their patrols, arrests, and street-level violence operate as a permanent reminder that women’s bodies are the terrain on which the state asserts control. This Islamist order, as Makaremi shows, is built on gender segregation as the primary method of governing the social body, with the compulsory headscarf as its most visible and effective manifestation. The book documents women dragged from pavements and cafés, beaten in vans and detention centres, humiliated in public view, and psychologically broken in custody, not as excesses but as routine techniques of rule.

Makaremi situates this state violence within a long history of feminist defiance, from the anti-veil protests of 1979 to student mobilizations in the 1990s and 2000s, underground feminist networks, digital refusals, and anti-harassment campaigns. These forms of dissent have been repeatedly criminalized, with the activists being exiled, disappeared, or turned into political prisoners whose bodies bear the archive of punishment. Testimonies in the book recount women incarcerated and tortured for refusing the state’s gender order, their captivity weaponized to terrorize entire communities into compliance. The Woman, Life, Freedom uprising thus does not erupt from nowhere; rather, it stands on the accumulated grief, rebellion, and refusal of generations of women who have lived and resisted under siege.

The Islamic Republic, as Makaremi carefully lays out, was not merely theocratic in structure. It was hierarchical in every sense: Persian and Shiite supremacist, patriarchal, militarised, and extractive. Amini’s real name—Jina Mahsa Amini—itself tells the story of domination. “Jina” is a Kurdish name. It could not legally appear on her identity documents, because the Iranian state prohibits Kurdish names as part of its project of Persian supremacist nation-making. Makaremi uses this erasure as an entry point to reveal how entire populations inside Iran are governed as internal minorities to be disciplined, silenced, or assimilated. Kurdish regions face intensified militarisation, surveillance, and punishment; cultural expression is criminalised; language is suppressed; and collective memory is targeted for deletion.

Woman! Life! Freedom! maps a wider terrain of daily violence borne by Balochis, Arabs, Baha’is, and by the more than five million Afghan refugees and their children born in Iran, all forced to live without rights, visibility, or protection. In this landscape of layered exclusion, the Kurdish feminist slogan, “Woman, Life, Freedom,” becomes not a poetic outcry, but an insurgent grammar forged from lives lived under racialized, gendered, and national subjugation.

Since the early 20th century, successive governments in Iran imposed what Makaremi calls “colonial government from within,” using internal domination as a tool of consolidation. Regions rich in natural resources were turned into zones of extractivist plunder; military-security complexes were strengthened; and neoliberal reforms in the 1990s dismantled what little labour protection had existed. Workers who once had secure contracts, especially those in the vital oil sector, were pushed into precarious, temporary jobs, forced to survive without safety nets, and often without months of back wages.

This “new labour lawlessness” was accompanied by what Makaremi chillingly refers to as “governance of the living through the dead.” During the post-revolution violent crackdowns of the 1980s, political dissent was exterminated, literally, to consolidate Ayatollah Khomeini’s power. Dissenting parties and movements were silenced through executions, exile, and disappearances. Families of the disappeared were harassed, watched, and psychologically broken. A culture of mourning without closure thus became a tool of control.

Public life itself was reshaped to accommodate the spectre of this terror. The consolidation of power also meant the rise of the Revolutionary Guard Corps—an institution with military, intelligence, and economic powers, positioned outside public accountability and under the direct control of the Supreme Leader. In post-war Iran, reconstruction was not about care; it was a conduit for accumulation by the ruling clergy and the Guards. Misappropriation of public funds was common; basic necessities like drinking water in the south-west became inaccessible, not simply due to climate change, but because of decades of corruption and neglect. The public infrastructure, which was once a promise of post-revolution prosperity, was cannibalized.

As neoliberal policies widened the gap between the rich and poor, a new class of elite emerged, flaunting their opulence on social media under accounts like “Rich Kids of Tehran.” Their Westernized, luxurious lifestyle stood in grotesque contrast to the everyday realities of millions: inflation crossing 40%, unpaid salaries, and disappearing welfare. Law enforcement, rather than mediating these tensions, became its brutal enforcer.

Makaremi’s book asks us to see the 2022 uprising not as a flash in the pan, but as the culmination of a long, festering wound. The rebellion is not against a single law or the veil—it is against an entire architecture of dispossession, inequality, and state-engineered mourning. The fires in the streets are not spontaneous—they are ancestral.

Veil as Weapon, Veil as Refusal

In vivid street scenes following Amini’s death, women cut their hair in public, twirled their scarves in the air, and burned them in the fire while dancing. Crowds joined in, chanting “Woman of honor! Woman of honor!” These acts of refusal were political, public, and deeply feminist, symbolizing the refusal of state control over the female body.

Makaremi’s critique is grounded in a decolonial feminist perspective. The Western obsession with the veil, she reminds us, is a colonial hangover rooted in the French and British civilizing missions that imagined Muslim women as in need of saving through unveiling. But this gaze, which sees the veil as always-already oppressive, is profoundly disconnected from the lived realities of Iranian women. Makaremi thus disrupts the Western gaze. Instead, she foregrounds how Iranian women reclaimed the veil as a symbol of defiance—turning its meaning against both the Islamic Republic and the West’s orientalist fantasies. The veil, in this context, became not a garment of subjugation but a strategic object in the choreography of dissent.

The issue, Makaremi insists, is not the veil itself but the obligation to wear it. Post-1979, the compulsory veil became the Islamic Republic’s most visible tool of asserting power over public space. But Iranian women do not experience the veil with the sense of otherness often projected by Western observers. It is familiar, as worn by beloved grandmothers, mothers, and friends. The protest is not about alienation from the veil, but resistance to being forced into it.

In contrast, Makaremi notes that in Europe, a veiled woman is often heckled, told she is “no longer in her country,” or treated as a threat to secular purity. Here, veiling appears as a site onto which xenophobia is projected and performed; hostility to the veil is less a feminist stance than a racialised politics of belonging. In that sense, the Western obsession with unveiling has nothing to do with Iranian women’s struggle.

In Iran, the veil, thus, became the entry point into a larger, suffocating system that scripts how women may walk, speak, laugh, study, protest, or simply exist. By forcing it, the state makes women’s bodies the surface on which law, ideology, and obedience are inscribed. The humiliation of being stopped on the street, the fear of being dragged into a van, the knowledge that one’s hair, body, and gesture are under constant watch were not incidental experiences, but the grammar through which the exercise of power was made intimate. What was being rejected, then, was not tradition but domination; not culture but compulsion; not faith but the violence done in its name.

The revolt, then, was not a modest reformist plea, but a direct challenge to theocratic sovereignty itself, to the fusion of religion and state power that has made dissent, love, intimacy, and even grief subject to surveillance and punishment.

Makaremi thus frames Woman, Life, Freedom as the inheritor of a long feminist and democratic struggle: one that demands not only gender justice but the dismantling of Persian–Shiite supremacist rule, the recognition of ethnic minorities, and an end to racialised state violence against minorities. The Kurdish slogan embodied the rebellion’s refusal of a nation built on erasure. “Woman, Life, Freedom” thus names not a momentary protest, but an abolitionist vision, a feminist insurrection against the totality of ideological and authoritarian domination.

In this light, the slogan “Woman, Life, Freedom” resonated across class, ethnic, and gender lines—men and women alike, from cities, towns, and rich and poor neighborhoods, joined the protests. The veil became the most legible and accessible symbol through which to reject authoritarian control. In burning it, women were not seeking Western liberation, but rather making a demand rooted in their own histories and context.

Importantly, these acts were not merely acts of courage but also of creativity and joy. Public defiance was performed not with just rage but with laughter, dance, and song, signifying not only opposition but a new mode of being. The veil, in its imposed significance, became a uniquely powerful tool through which women could signal refusal. As Fanon once wrote, “this woman who sees without being seen frustrates the colonizer.”

The Grammar of Resistance

What does it mean to raise your voice when everything around you tells you to remain silent? In the Iran of 2022, it meant rewriting the very grammar of resistance. ‘Woman’ in the rallying cry of “Woman, Life, Freedom” was no longer just the female subject. She was also the incipient rebel, the schoolgirl who tore out the Supreme Leader’s photo from her textbook, who refused to wear the hijab in school assemblies. These girls carried the memory of their foremothers; those who rose in 1979 and again in the 2000s, but they brought with them something new: a total abandonment of fear. The trauma that once governed silence had run its course. Gen Z, as Makaremi writes, “abandoned the transmission chain.” They marched with middle fingers raised, laughing in the face of tyranny.

In the streets, resistance danced. It tossed turbans off the heads of clerics with swift, mischievous grace. Young men and women, in acts of joyful defiance, followed robed figures onto buses and escalators, flicking off their turbans and fleeing into the crowd—merry, victorious. These were choreographies of refusal: rejections of hierarchy, attacks on the manufactured sanctity of patriarchal authority. A turban in mid-air became a symbol of a toppled pedestal.

And still, the most profound expressions of resistance were etched in grief. The mothers who had lost their children in previous uprisings, from 2017 to 2019, were once broken, silenced, and isolated. But slowly, their mourning became militant. Human rights activists gathered their testimonies, and in doing so, these women transformed from bereaved mothers to Madaran-e dad-kha (Mothers for Justice). Their sorrow, once private and criminalized, became a collective defiance. They met in homes, embraced, drank tea, and spoke their children’s names. Their pain became political. Their love became language. Their gatherings became a protest.

This was affective resistance: refusal shaped by sorrow, solidarity built on broken hearts. It was filmed, whispered, uploaded, and shared. These maternal testimonies, powered by open-ended mourning and unrelenting loyalty to the dead, refused the binaries of justice and vengeance. The line blurred. They became each other’s strength—and the regime’s nightmare.

Elsewhere, the resistance wove through bazaars, even as economic collapse gripped the people. Shopkeepers risked everything in solidarity strikes. Students reimagined revolt. At lunch, they tore down gender-segregated canteen walls, spread picnic blankets on university lawns, and dared to sit together as equals. Even these blankets became contraband. Surveillance extended not just to masks or leaflets, but to any object that hinted at joy, solidarity, or disruption of order.

These uprisings were not unified in command, but they were rhythmic—pulsing with moments of bravery, irreverence, and imagination. They produced a “we” that refused the grammar of submission. The state sought to criminalize dissent, but the people rewrote the rules. Women! Life! Freedom! is a searing testament to the courage of a people who dared to dream beyond repression. Through memory, rage, and refusal, Makaremi reveals how resistance pulses through bodies, images, and grief. This is not just a book; it is the echo of a revolution in motion.

Makaremi’s book enters the feminist canon not as documentation of a single revolt but as a counter-archive of a people who have refused to be disciplined in silence. It unsettles two dominant gazes at once: the Western gaze that imagines Iranian women only as veiled victims and the state’s gaze that demands women’s obedience as proof of national purity. By braiding Kurdish dispossession with feminist rebellion, prison testimonies with street defiance, and mourning with mobilization, Makaremi shows that Woman, Life, Freedom is neither sudden nor symbolic; it is the living continuation of a century of dissent carried in women’s bodies, households, friendships, and clandestine organizing. She thus turns feminist analysis away from parliaments and policy toward the granular sites where power is felt and where revolt gestates: the bus, the factory, the hair salon, the classroom, the refugee neighbourhood, the grave.

We are again witnessing a surge in mass protests across Iran as people demand justice and political change. The state has been responding with new technologies of control, new raids, new prisons, and yet the words “Woman, Life, Freedom” have already outlived their fear. They have migrated into language, into art, into diasporic solidarity, into the moral imagination of a generation that no longer consents to live as the governed dead. Makaremi’s book leaves us with the knowledge that what has been set in motion cannot be unmade: a feminist, decolonial, and anti-authoritarian revolution of meaning, one that may unfold slowly, unevenly, invisibly, but is irreversible.

Related Posts

Woman! Life! Freedom!: A Counter-Archive of Defiance and Survival in Iran

In 2022, the echo of the slogan, “Jin, Jiyan, Azadi” (“Woman, Life, Freedom”), reverberated far beyond Iran’s borders. The images were unforgettable: young Iranian women setting their veils on fire, cutting their hair in public defiance, dancing bareheaded in the streets. The courage was raw and collective. But what lies beneath this spectacle of resistance? What is the anatomy of such an uprising, and what silences and struggles precede the moment when revolt bursts onto the streets?

In her 2025 book Woman! Life! Freedom! Echoes of a Revolutionary Uprising in Iran, political anthropologist and feminist Chowra Makaremi takes us to the heart of feminist resistance in Iran. She does not offer simple explanations. Instead, she weaves together personal memory, historical excavation, and ethnographic insight to trace the trajectory of Iranian society that led to this revolutionary moment. She asks: What does it mean to resist in a state that kills, silences, and forgets? How do women carry intergenerational trauma while also holding the charge of liberation?

What emerges in Woman! Life! Freedom! is a long and tangled history of power and resistance, refracted not only through political theory or scholarly detachment, but also through the intimate and embodied lens of Makaremi herself—an anthropologist, a woman in exile, and the daughter of a revolutionary, her mother, Fatemeh Zarei, and aunt having been jailed and executed by the state in the 1980s.

Her mother becomes a spectral presence throughout the text, as does her maternal grandfather’s 2011 memoir Aziz’s Notebook: At the Heart of the Iranian Revolution, which she discovered and translated decades after it was written at the height of state repression during Khomeini’s regime in Iran.

Translated from the French by Maya Judd, Makaremi’s book resists the sanitized language of conventional political analysis. She does not shy away from this proximity to violence; instead, she wields it as a feminist method, positioning memory as resistance, grief as an archive, and subjectivity as a valid and urgent site of knowledge.

Makaremi’s commitment to counter-archives—those informal, fugitive, and affect-laden records of dissent—refuses to separate the emotional from the political. Through testimonies, chants, photographs, social media videos, and her own recollections, she constructs a living, breathing archive of rebellion. This is not just a documentation of revolt, but an invocation: a call to remember, to mourn, and to rise.

The Long Wound of Authoritarianism

On 16 September 2022, 22-year-old Kurdish-Iranian woman, Jina (Mahsa) Amini, died after being arrested, taken to the “re-education centre” run by the morality police under Iran’s hijab laws, and beaten in custody. Amini’s death resonated with women in Iran not just as an incident of state violence, but as a mirror of their own precarity and erasure. “Identifying with Jina’s fate,” Makaremi writes, “made her death a political and emotional ordeal for Iranian women within and outside the country and for many women around the world.” In Woman! Life! Freedom! Makaremi traces the anatomy of this fire, showing us that revolt is rarely sudden—it is built, layer by layer, by lives lived under siege.

The Gasht-e Ershad (“morality police”), established in 2005, is not a marginal force but a central technology of the Islamic Republic’s gendered statecraft: a roving apparatus authorised to surveil, detain, and publicly punish women for violating compulsory hijab laws or perceived moral codes. Their patrols, arrests, and street-level violence operate as a permanent reminder that women’s bodies are the terrain on which the state asserts control. This Islamist order, as Makaremi shows, is built on gender segregation as the primary method of governing the social body, with the compulsory headscarf as its most visible and effective manifestation. The book documents women dragged from pavements and cafés, beaten in vans and detention centres, humiliated in public view, and psychologically broken in custody, not as excesses but as routine techniques of rule.

Makaremi situates this state violence within a long history of feminist defiance, from the anti-veil protests of 1979 to student mobilizations in the 1990s and 2000s, underground feminist networks, digital refusals, and anti-harassment campaigns. These forms of dissent have been repeatedly criminalized, with the activists being exiled, disappeared, or turned into political prisoners whose bodies bear the archive of punishment. Testimonies in the book recount women incarcerated and tortured for refusing the state’s gender order, their captivity weaponized to terrorize entire communities into compliance. The Woman, Life, Freedom uprising thus does not erupt from nowhere; rather, it stands on the accumulated grief, rebellion, and refusal of generations of women who have lived and resisted under siege.

The Islamic Republic, as Makaremi carefully lays out, was not merely theocratic in structure. It was hierarchical in every sense: Persian and Shiite supremacist, patriarchal, militarised, and extractive. Amini’s real name—Jina Mahsa Amini—itself tells the story of domination. “Jina” is a Kurdish name. It could not legally appear on her identity documents, because the Iranian state prohibits Kurdish names as part of its project of Persian supremacist nation-making. Makaremi uses this erasure as an entry point to reveal how entire populations inside Iran are governed as internal minorities to be disciplined, silenced, or assimilated. Kurdish regions face intensified militarisation, surveillance, and punishment; cultural expression is criminalised; language is suppressed; and collective memory is targeted for deletion.

Woman! Life! Freedom! maps a wider terrain of daily violence borne by Balochis, Arabs, Baha’is, and by the more than five million Afghan refugees and their children born in Iran, all forced to live without rights, visibility, or protection. In this landscape of layered exclusion, the Kurdish feminist slogan, “Woman, Life, Freedom,” becomes not a poetic outcry, but an insurgent grammar forged from lives lived under racialized, gendered, and national subjugation.

Since the early 20th century, successive governments in Iran imposed what Makaremi calls “colonial government from within,” using internal domination as a tool of consolidation. Regions rich in natural resources were turned into zones of extractivist plunder; military-security complexes were strengthened; and neoliberal reforms in the 1990s dismantled what little labour protection had existed. Workers who once had secure contracts, especially those in the vital oil sector, were pushed into precarious, temporary jobs, forced to survive without safety nets, and often without months of back wages.

This “new labour lawlessness” was accompanied by what Makaremi chillingly refers to as “governance of the living through the dead.” During the post-revolution violent crackdowns of the 1980s, political dissent was exterminated, literally, to consolidate Ayatollah Khomeini’s power. Dissenting parties and movements were silenced through executions, exile, and disappearances. Families of the disappeared were harassed, watched, and psychologically broken. A culture of mourning without closure thus became a tool of control.

Public life itself was reshaped to accommodate the spectre of this terror. The consolidation of power also meant the rise of the Revolutionary Guard Corps—an institution with military, intelligence, and economic powers, positioned outside public accountability and under the direct control of the Supreme Leader. In post-war Iran, reconstruction was not about care; it was a conduit for accumulation by the ruling clergy and the Guards. Misappropriation of public funds was common; basic necessities like drinking water in the south-west became inaccessible, not simply due to climate change, but because of decades of corruption and neglect. The public infrastructure, which was once a promise of post-revolution prosperity, was cannibalized.

As neoliberal policies widened the gap between the rich and poor, a new class of elite emerged, flaunting their opulence on social media under accounts like “Rich Kids of Tehran.” Their Westernized, luxurious lifestyle stood in grotesque contrast to the everyday realities of millions: inflation crossing 40%, unpaid salaries, and disappearing welfare. Law enforcement, rather than mediating these tensions, became its brutal enforcer.

Makaremi’s book asks us to see the 2022 uprising not as a flash in the pan, but as the culmination of a long, festering wound. The rebellion is not against a single law or the veil—it is against an entire architecture of dispossession, inequality, and state-engineered mourning. The fires in the streets are not spontaneous—they are ancestral.

Veil as Weapon, Veil as Refusal

In vivid street scenes following Amini’s death, women cut their hair in public, twirled their scarves in the air, and burned them in the fire while dancing. Crowds joined in, chanting “Woman of honor! Woman of honor!” These acts of refusal were political, public, and deeply feminist, symbolizing the refusal of state control over the female body.

Makaremi’s critique is grounded in a decolonial feminist perspective. The Western obsession with the veil, she reminds us, is a colonial hangover rooted in the French and British civilizing missions that imagined Muslim women as in need of saving through unveiling. But this gaze, which sees the veil as always-already oppressive, is profoundly disconnected from the lived realities of Iranian women. Makaremi thus disrupts the Western gaze. Instead, she foregrounds how Iranian women reclaimed the veil as a symbol of defiance—turning its meaning against both the Islamic Republic and the West’s orientalist fantasies. The veil, in this context, became not a garment of subjugation but a strategic object in the choreography of dissent.

The issue, Makaremi insists, is not the veil itself but the obligation to wear it. Post-1979, the compulsory veil became the Islamic Republic’s most visible tool of asserting power over public space. But Iranian women do not experience the veil with the sense of otherness often projected by Western observers. It is familiar, as worn by beloved grandmothers, mothers, and friends. The protest is not about alienation from the veil, but resistance to being forced into it.

In contrast, Makaremi notes that in Europe, a veiled woman is often heckled, told she is “no longer in her country,” or treated as a threat to secular purity. Here, veiling appears as a site onto which xenophobia is projected and performed; hostility to the veil is less a feminist stance than a racialised politics of belonging. In that sense, the Western obsession with unveiling has nothing to do with Iranian women’s struggle.

In Iran, the veil, thus, became the entry point into a larger, suffocating system that scripts how women may walk, speak, laugh, study, protest, or simply exist. By forcing it, the state makes women’s bodies the surface on which law, ideology, and obedience are inscribed. The humiliation of being stopped on the street, the fear of being dragged into a van, the knowledge that one’s hair, body, and gesture are under constant watch were not incidental experiences, but the grammar through which the exercise of power was made intimate. What was being rejected, then, was not tradition but domination; not culture but compulsion; not faith but the violence done in its name.

The revolt, then, was not a modest reformist plea, but a direct challenge to theocratic sovereignty itself, to the fusion of religion and state power that has made dissent, love, intimacy, and even grief subject to surveillance and punishment.

Makaremi thus frames Woman, Life, Freedom as the inheritor of a long feminist and democratic struggle: one that demands not only gender justice but the dismantling of Persian–Shiite supremacist rule, the recognition of ethnic minorities, and an end to racialised state violence against minorities. The Kurdish slogan embodied the rebellion’s refusal of a nation built on erasure. “Woman, Life, Freedom” thus names not a momentary protest, but an abolitionist vision, a feminist insurrection against the totality of ideological and authoritarian domination.

In this light, the slogan “Woman, Life, Freedom” resonated across class, ethnic, and gender lines—men and women alike, from cities, towns, and rich and poor neighborhoods, joined the protests. The veil became the most legible and accessible symbol through which to reject authoritarian control. In burning it, women were not seeking Western liberation, but rather making a demand rooted in their own histories and context.

Importantly, these acts were not merely acts of courage but also of creativity and joy. Public defiance was performed not with just rage but with laughter, dance, and song, signifying not only opposition but a new mode of being. The veil, in its imposed significance, became a uniquely powerful tool through which women could signal refusal. As Fanon once wrote, “this woman who sees without being seen frustrates the colonizer.”

The Grammar of Resistance

What does it mean to raise your voice when everything around you tells you to remain silent? In the Iran of 2022, it meant rewriting the very grammar of resistance. ‘Woman’ in the rallying cry of “Woman, Life, Freedom” was no longer just the female subject. She was also the incipient rebel, the schoolgirl who tore out the Supreme Leader’s photo from her textbook, who refused to wear the hijab in school assemblies. These girls carried the memory of their foremothers; those who rose in 1979 and again in the 2000s, but they brought with them something new: a total abandonment of fear. The trauma that once governed silence had run its course. Gen Z, as Makaremi writes, “abandoned the transmission chain.” They marched with middle fingers raised, laughing in the face of tyranny.

In the streets, resistance danced. It tossed turbans off the heads of clerics with swift, mischievous grace. Young men and women, in acts of joyful defiance, followed robed figures onto buses and escalators, flicking off their turbans and fleeing into the crowd—merry, victorious. These were choreographies of refusal: rejections of hierarchy, attacks on the manufactured sanctity of patriarchal authority. A turban in mid-air became a symbol of a toppled pedestal.

And still, the most profound expressions of resistance were etched in grief. The mothers who had lost their children in previous uprisings, from 2017 to 2019, were once broken, silenced, and isolated. But slowly, their mourning became militant. Human rights activists gathered their testimonies, and in doing so, these women transformed from bereaved mothers to Madaran-e dad-kha (Mothers for Justice). Their sorrow, once private and criminalized, became a collective defiance. They met in homes, embraced, drank tea, and spoke their children’s names. Their pain became political. Their love became language. Their gatherings became a protest.

This was affective resistance: refusal shaped by sorrow, solidarity built on broken hearts. It was filmed, whispered, uploaded, and shared. These maternal testimonies, powered by open-ended mourning and unrelenting loyalty to the dead, refused the binaries of justice and vengeance. The line blurred. They became each other’s strength—and the regime’s nightmare.

Elsewhere, the resistance wove through bazaars, even as economic collapse gripped the people. Shopkeepers risked everything in solidarity strikes. Students reimagined revolt. At lunch, they tore down gender-segregated canteen walls, spread picnic blankets on university lawns, and dared to sit together as equals. Even these blankets became contraband. Surveillance extended not just to masks or leaflets, but to any object that hinted at joy, solidarity, or disruption of order.

These uprisings were not unified in command, but they were rhythmic—pulsing with moments of bravery, irreverence, and imagination. They produced a “we” that refused the grammar of submission. The state sought to criminalize dissent, but the people rewrote the rules. Women! Life! Freedom! is a searing testament to the courage of a people who dared to dream beyond repression. Through memory, rage, and refusal, Makaremi reveals how resistance pulses through bodies, images, and grief. This is not just a book; it is the echo of a revolution in motion.

Makaremi’s book enters the feminist canon not as documentation of a single revolt but as a counter-archive of a people who have refused to be disciplined in silence. It unsettles two dominant gazes at once: the Western gaze that imagines Iranian women only as veiled victims and the state’s gaze that demands women’s obedience as proof of national purity. By braiding Kurdish dispossession with feminist rebellion, prison testimonies with street defiance, and mourning with mobilization, Makaremi shows that Woman, Life, Freedom is neither sudden nor symbolic; it is the living continuation of a century of dissent carried in women’s bodies, households, friendships, and clandestine organizing. She thus turns feminist analysis away from parliaments and policy toward the granular sites where power is felt and where revolt gestates: the bus, the factory, the hair salon, the classroom, the refugee neighbourhood, the grave.

We are again witnessing a surge in mass protests across Iran as people demand justice and political change. The state has been responding with new technologies of control, new raids, new prisons, and yet the words “Woman, Life, Freedom” have already outlived their fear. They have migrated into language, into art, into diasporic solidarity, into the moral imagination of a generation that no longer consents to live as the governed dead. Makaremi’s book leaves us with the knowledge that what has been set in motion cannot be unmade: a feminist, decolonial, and anti-authoritarian revolution of meaning, one that may unfold slowly, unevenly, invisibly, but is irreversible.

SUPPORT US

We like bringing the stories that don’t get told to you. For that, we need your support. However small, we would appreciate it.