What’s Lost and What’s Left Behind Amidst the Migration Woes of Uttarakhand: Preserving the Heritage

In the hill state of Uttarakhand, the Tharu tribe is the most populous tribal community, constituting 0.8% of the state’s population. The Tharus have historically lived on both sides of the Indo-Nepal border in Uttarakhand, Uttar Pradesh, and Bihar. In Uttarakhand, they reside in the Terai lowlands, which, unlike the steep Himalayan hill districts, offer flat terrain, fertile land, road and rail links to the plains, and proximity to major markets in UP and Delhi. This made Terai a key area of developmental extraction and rapid industrialization for the state.

The establishment of the State Infrastructure and Industrial Development Corporation of Uttarakhand Ltd (SIIDCUL) after 2002 in the Terai region led to rapid land acquisition by industries, affecting the habitation of the indigenous Tharu population. Faced with depleting grasslands and the difficulty of assimilating with the new developments, the tribe’s traditions, lifestyle, and rich weaving culture have undergone gradual erosion.

They have traditionally worshipped the land goddess, Bhumsen, and nurtured an ecologically harmonious lifestyle. Sourcing cordgrass, or kaas, from the tall grasslands, as well as other readily available materials, the community developed a sophisticated weaving culture that was passed down through the generations. Grass is collected before the monsoon, and left to dry till the end of the season, when the blades become pliable for weaving.

The Tharus used these woven baskets to store grains, clothes, and also for traditional cooking. Colourful baskets made by interweaving feathers and wool were used for gifting during traditional marriage ceremonies. A rapid lifestyle shift in the region and outward migration of the tribal population make these traditional Tharu baskets a rare commodity.

The issue of outward migration remains untackled in a state that was formed 25 years ago, with the vision of supposed ecologically sustainable development in the hills. The tribes from the hill regions, namely Bhotia, Jaunsari, and Raji, as listed by the Tribal Research Institute, Uttarakhand, migrate to the nearby towns and cities in the plains for better opportunities, education, and healthcare.

Migration has surged in the last few decades due to historic government neglect: a lack of connectivity to remote mountain villages, to basic education, healthcare, and employment opportunities. Climate change, compounded by conditions such as uncertain monsoon patterns in these ecologically sensitive mountain regions, makes agriculture a difficult choice. There is also woefully inadequate government assistance in horticulture or agriculture, leaving farmers to fend for themselves.

Prospects are also grim for the nomadic pastoral community of the Van Gujjars in Uttarakhand, who are primarily Muslims. They move between mountain pastures, or bugyals, in the summer and the lowlands during winter. From March to May, these forest dwellers battle for survival amidst forest fires, and during the monsoon, they face increasing losses of livestock due to floods.

The community is not just at the forefront of the climate crisis, but also vulnerable to the right-wing policy makers in the state. Eviction notices were served to 400 Van Gujjar households in May 2023, alleging encroachment of government land. Amidst theories of ‘Land Jihad’ floated by the BJP state government, the Muslim Van Gujjar community is scrambling to piece together the proofs of their native nomadic identity in the state.

The Devastating Impact of Outward Migration

Research published in the South Eastern European Journal of Public Health suggests that Pauri Garhwal, Bageshwar, and Uttarkashi are the worst-affected districts by migration woes in Uttarakhand. Each year, new ghost villages in Uttarakhand are documented with zero population in official studies and reports.

Semla, in Tehri District, a village comprising almost 50 households a few decades ago, now has a population of less than 10. Jhakot village in Pauri district is also abandoned, with all seven resident families having migrated to bigger nearby towns. Godi, in Kotdwar, is one of the many villages vacated due to human-wildlife conflict in recent times.

Partially abandoned villages are often gradually overtaken by wilderness, resulting in attacks by leopards and other wild animals, which pose a persistent threat to the remaining residents. After facing repeated destruction of crops by wild boars, monkeys, and other stray animals, locals often resort to abandoning their ancestral agricultural lands.

Through the last 25 years, loopholes in land laws have been exploited by the state to allow mass-scale land deals for resorts, wellness centres, and high-end private properties in eco-sensitive zones. In January 2025, for example, an incident of illegal tree-felling and the unauthorised use of heavy digging machinery for the construction of a resort surfaced in the Khairkhal Laldhang Forest Range.

26 trees were cut at the site, when permission granted by the forest department was for only 14 trees. Felled trees include Khair trees, which come under the protected category. Here, the revenue inspector had to visit the site and intervene three times before the work could finally stop.

Locals also allegedly accused the Tehsil Administration of negligence due to the influence of former Revenue Minister Prem Chand Aggarwal, whose son, Piyush Aggarwal, owns the project. Laldhang range officer (DFO) has now filed a case against Piyush for the illegal felling of trees. These remote eco-sensitive areas are prime properties, where encroachment and illegal construction in forest areas often go unchecked.

According to a report by The Print, until February 2025, non-locals were allowed to buy up to 12.5 acres of agricultural land in the state, with provisions to increase it. It was only after the public outcry for ‘Sashakt Bhoo Kanoon‘ or strict land laws that an amendment was enacted, placing a blanket ban on the purchase of agricultural and horticultural lands by non-locals, excluding only the lowland districts of Haridwar and Udham Singh Nagar. The measures were taken, according to CM Pushkar Singh Dhami, ‘to protect the state’s resources, cultural heritage and citizens’ rights.’

How this amended law is enforced is yet to be seen; however, many locals believe that irreparable damage has already been done to the hills with lakhs of hectares of forest and agricultural land lost due to encroachment and illegal construction. In more than 1700 of Uttarakhand’s remote ghost villages, elderly parents are often the last settlers left.

What’s lost in these empty villages is entire communities themselves, not to mention a thriving agrarian culture and the community’s inherent knowledge to live harmoniously with the fragile ecosystem around them. Festivals and rituals, often centred around their ancestral villages and land deities, gradually vanish to cultural assimilation and globalization, as do traditional medicines, dyeing techniques, woodwork, weaving techniques, and cuisine.

Preserving the Heritage

The task of preserving the tangible and intangible heritage of a place and community is a multifaceted process, primarily overseen by the Ministry of Culture. The Archaeological Survey of India (ASI), under the Ministry of Culture, also runs 52 site museums across India and has recently been the subject of controversy over its resource allocation. According to data presented in the parliament, 25% of ASI’s total budget was allocated to the state of PM Modi’s Gujarat between 2020 and 2025.

Further, out of the 8.5 crore spent in Gujarat, 8 crore (94%) was spent solely in Vadnagar, Prime Minister Modi’s hometown. During the ongoing excavations, ASI uncovered a settlement in Vadnagar dating back to 800 BC. A joint study by ASI and IIT Kharagpur was conducted that revealed the evidence of ‘cultural continuity’ in Vadnagar, Gujarat, after the collapse of the Harappan civilization, challenging the notion of a Dark Age in Indian history. At Vadnagar, a state-of-the-art, India’s largest archeological excavation experiential museum has also been built.

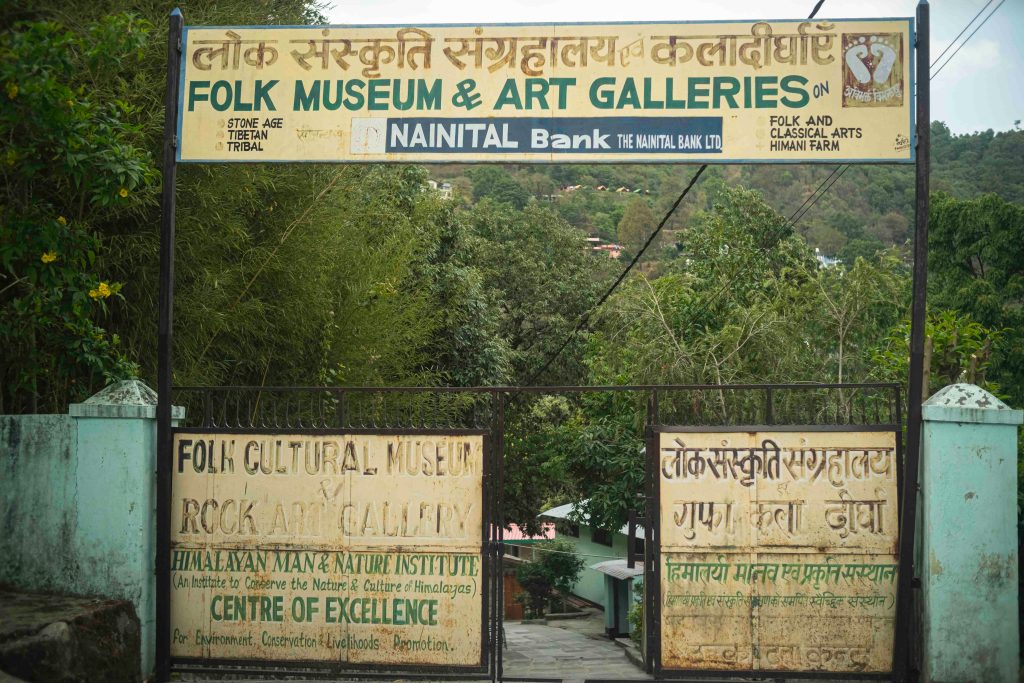

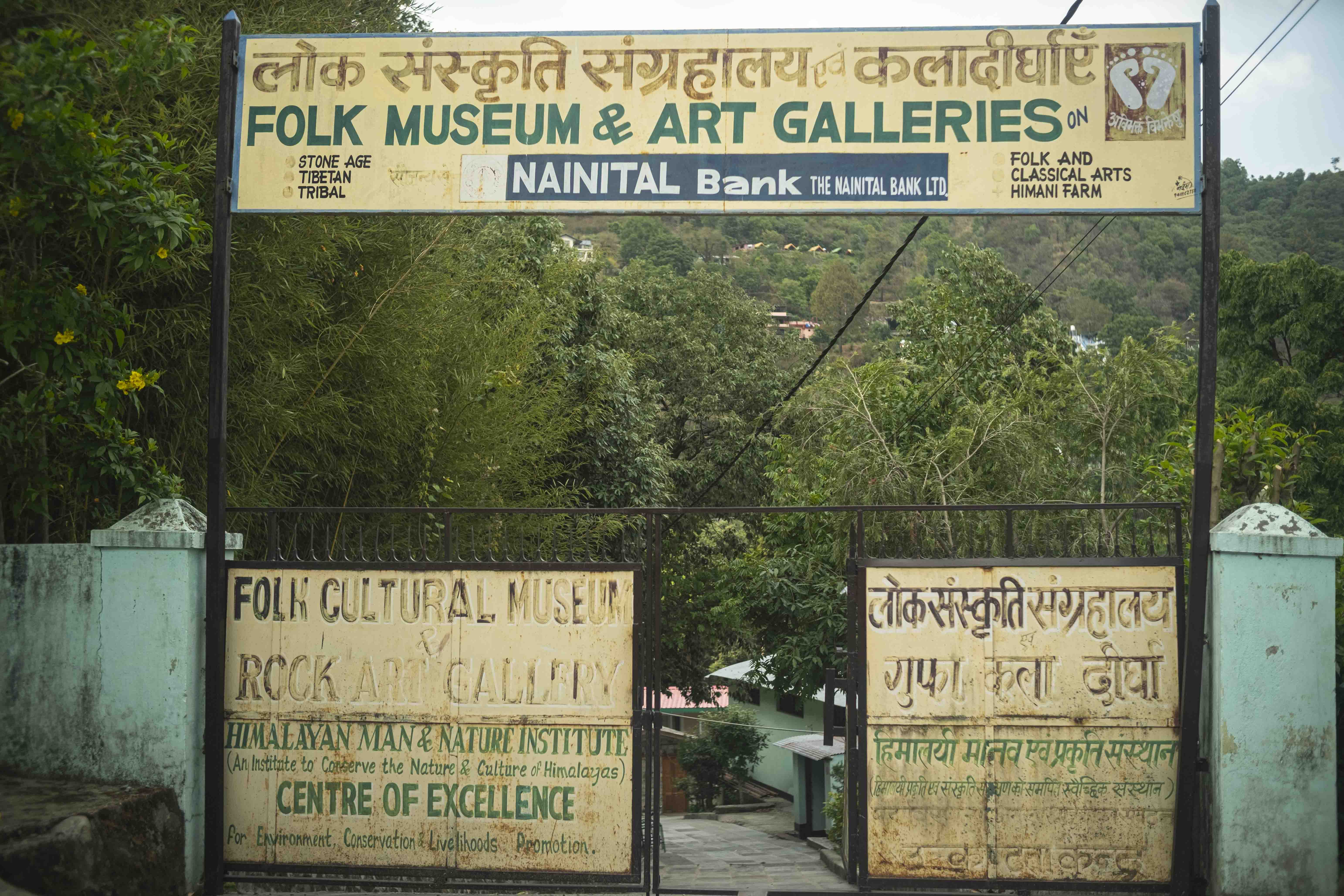

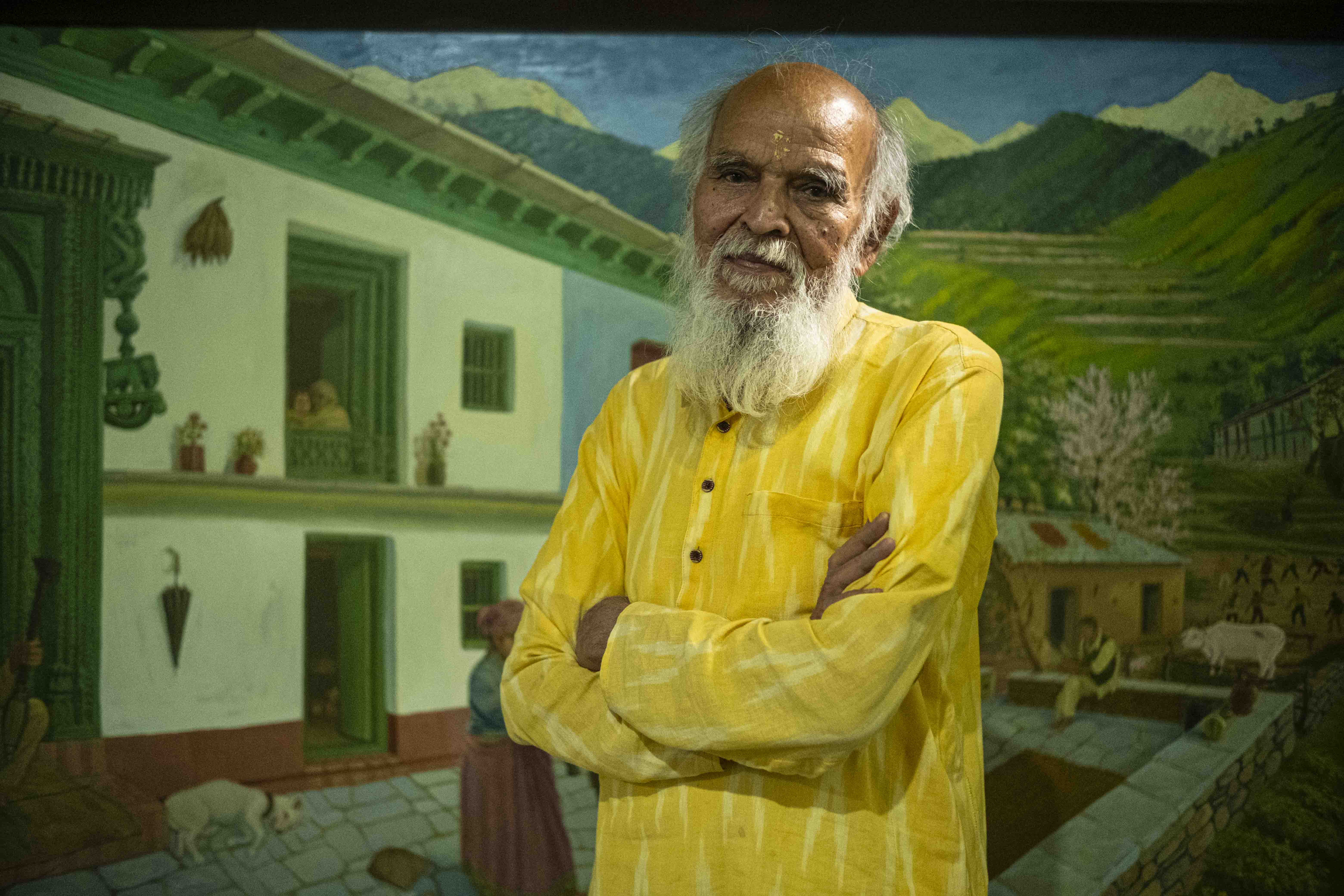

There are 38 museums in Uttarakhand listed on the Ministry’s official website. Of these, 18 operate under the Central government, 6 under the state government, and 14 others are run privately or by non-governmental organisations. The Lok Sanskriti Sangrahalay is one such privately run museum, founded by Dr Yashodhar Mathpal, a renowned artist, curator, and scholar whose study of Rock Art paintings in Bhimbetka is one of the most comprehensive research studies on India’s oldest prehistoric rock art site.

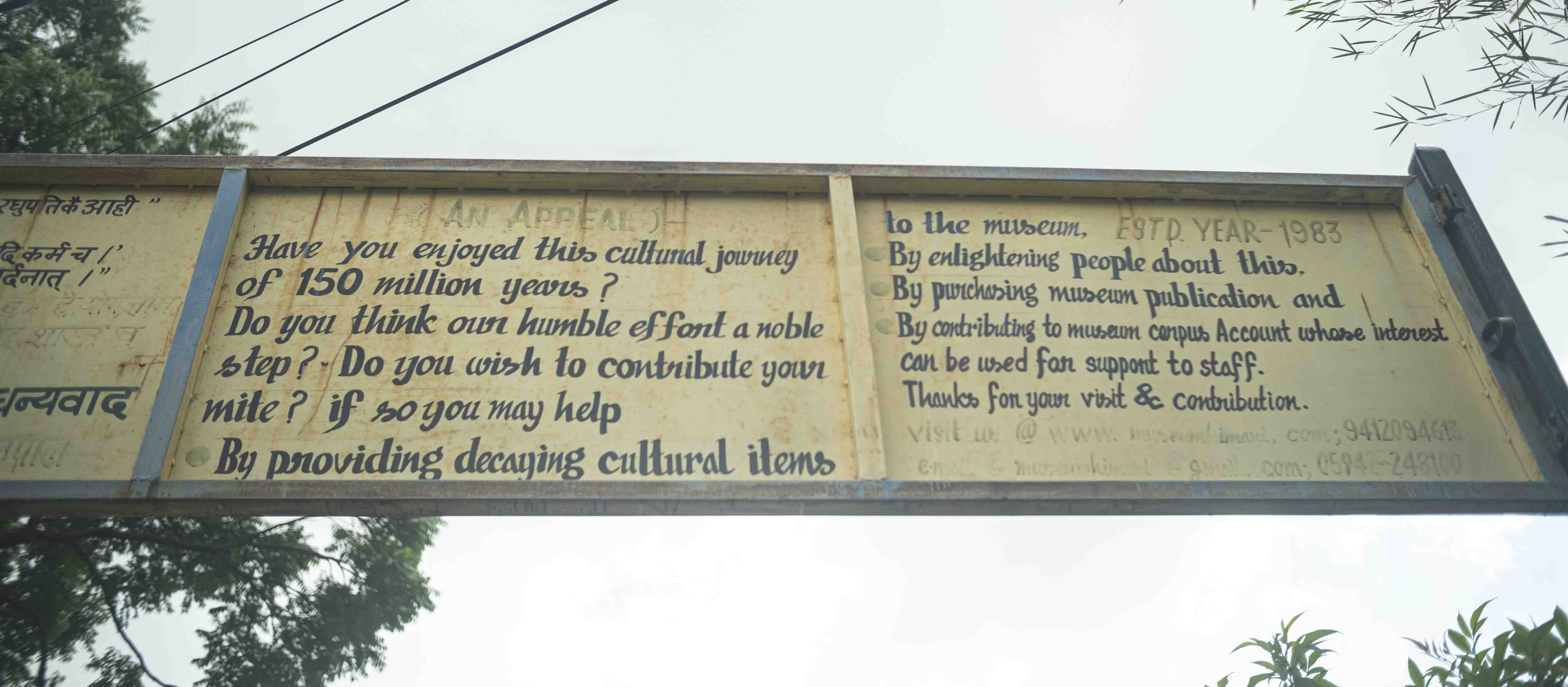

As an artist and curator, he worked with the Government of India to establish museums in Kerala and Central India. His vision to preserve the heritage of his land led him to set up Lok Sanskriti Sangrahalay in Uttarakhand in 1983.

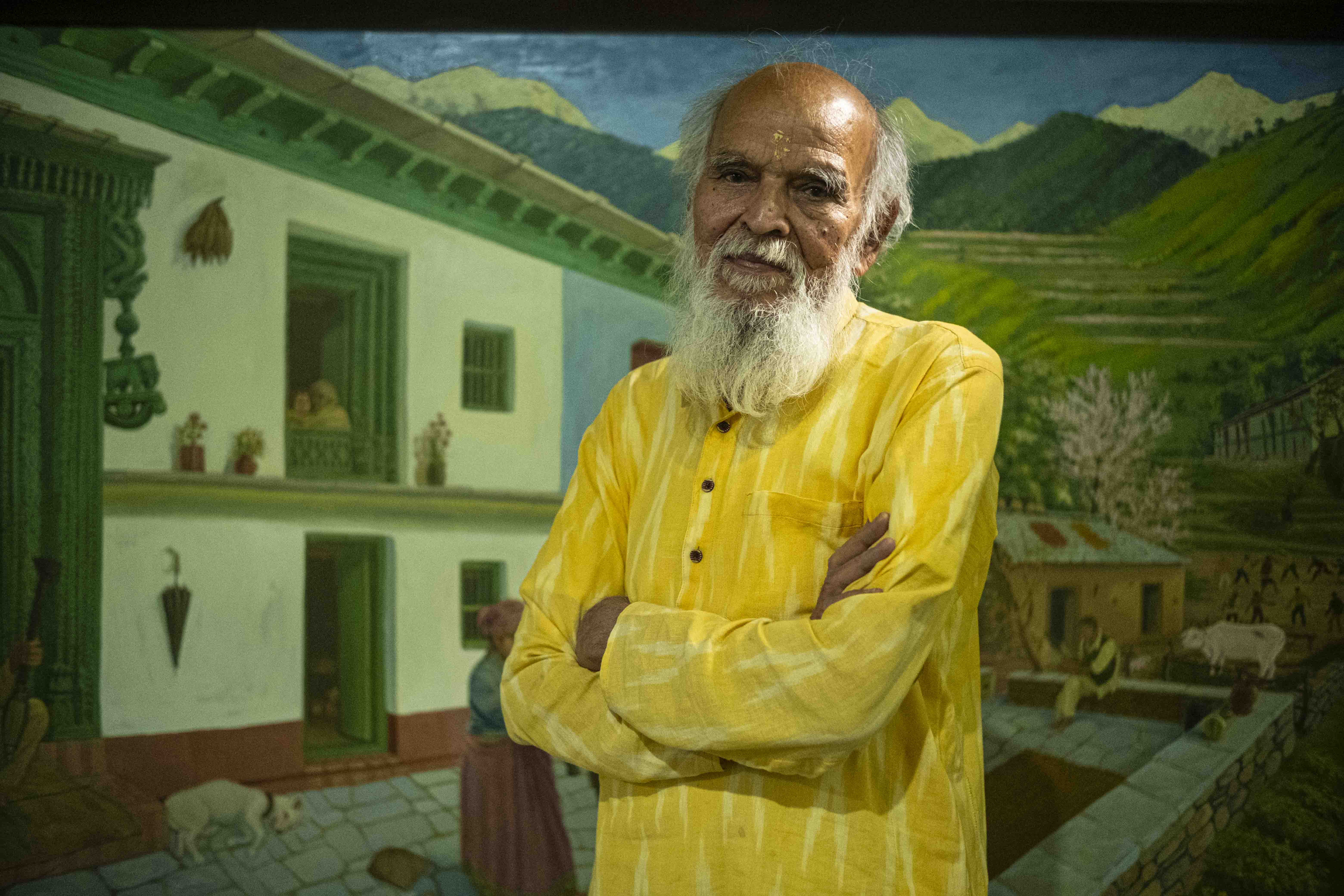

Aware of the systemic corruption, Dr Mathpal has been a crusader for the preservation of the heritage of the people of Uttarakhand. Climate change, illegal land acquisition, demographic changes, cultural assimilation, and the government’s systemic negligence– the threats are manifold. The Padma Shri awardee understands these threats of erasure that loom over the indigenous communities.

However, his primary focus for four decades has been on what can be saved from these abandoned villages, locked homes, and fields left behind by the ones who migrated. He has meticulously documented and exhibited the clothes, utensils, and objects of everyday use of all major tribes and communities of Uttarakhand at his museum.

Politicians and local authorities have repeatedly announced grants for the upkeep of the museum during political rallies and meetings, but no such funds were ever released to him. He was appointed the Vice President of the Literary and Cultural Council of Uttarakhand in 2005. He resigned a year later, citing deeply entrenched corruption in the bureaucratic system that misallocated or inflated budgets meant to support artists and cultural institutions. Despite no government aid, he has nurtured the Folk Cultural Museum as a space that helps piece together the identity of the people who have historically called these hills their home.

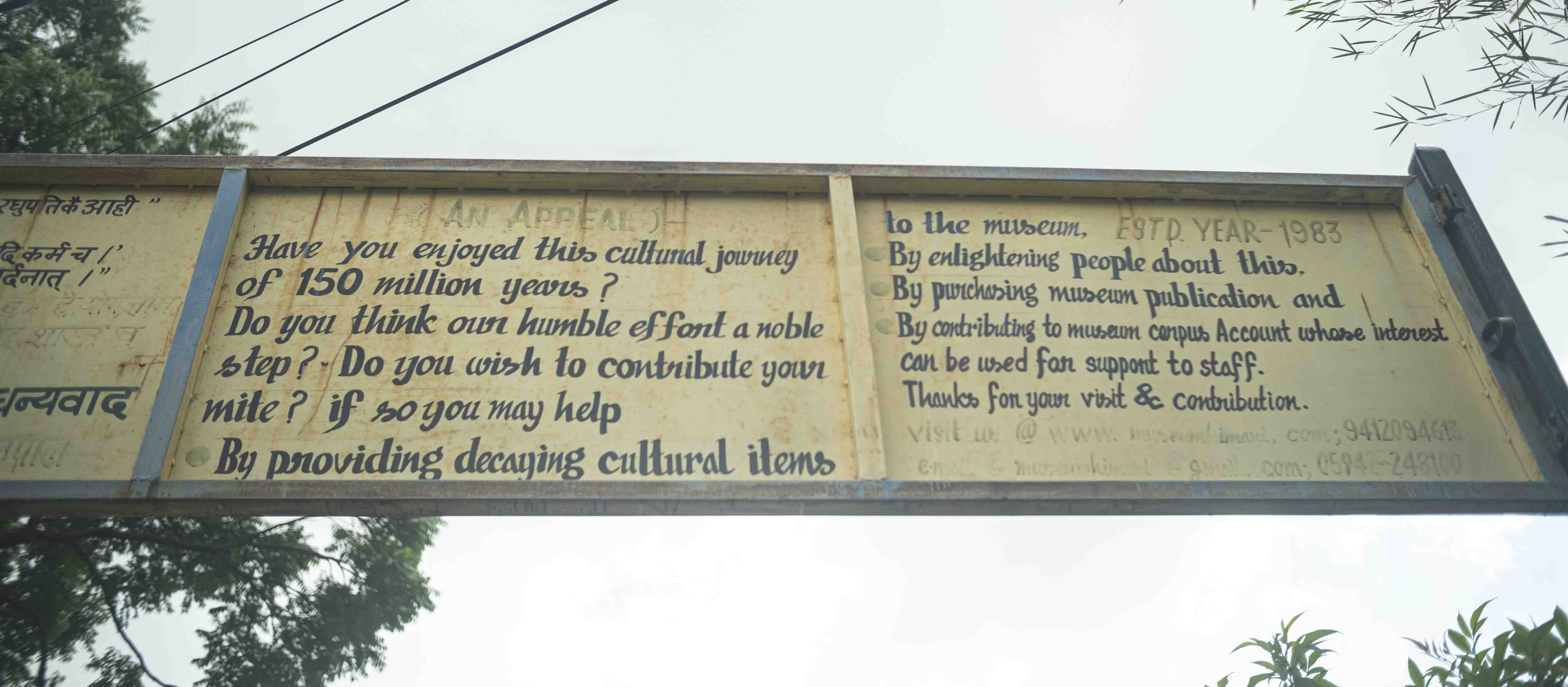

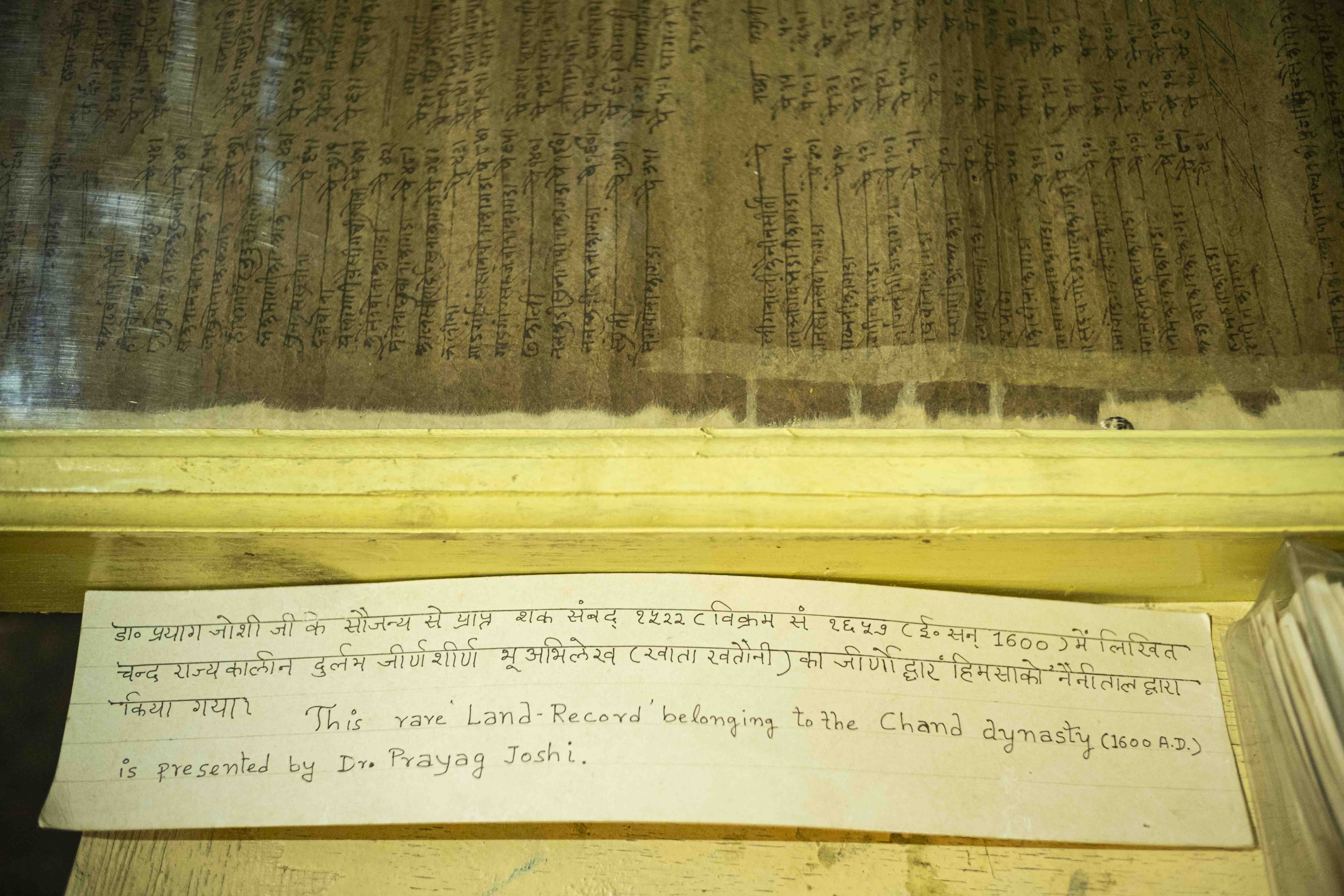

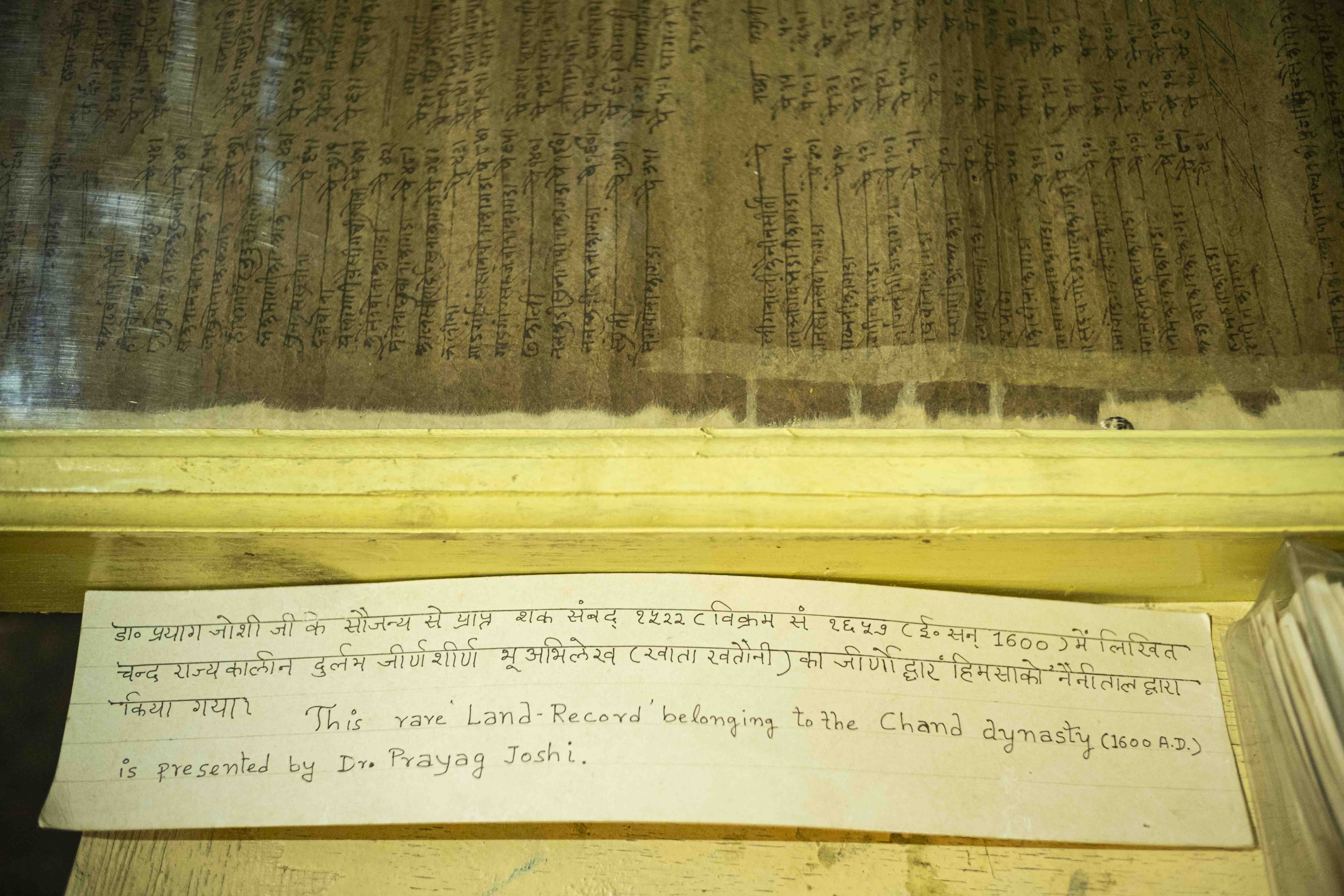

In archaeological terms, any man-made object more than 100 years old, or documents of relevance as old as 75 years, can be termed as ‘antiquity’, and this museum is replete with them. Since the museum’s inception, Dr Mathpal has appealed to locals and visitors to donate old utensils, agricultural equipment, land records, documents, and the smallest of objects that might be relevant to the past. At the museum, his carefully curated collection features antiquities acquired from local households, such as a 6th-century land record known as Badua Kagaz. And sometimes objects are unearthed from surrounding ravines and lakes, like weaponry from the Revolt of 1857 and agricultural equipment that is more than a century old.

Folk Cultural Museum

On the shelves at the museum are neatly placed traditional firestarters, baskets made of dry gourds, locally made paper, ink, combs, and traditional weighing cups called ser and mana. Bonda, Tauli, Bhaddu, all cooking utensils of yesteryear, made of brass, bronze, and ashtadhatu, or the eight metals once used by the people of these hills, are on display. On the corner shelf sits a Beoli Pitara, a 300-year-old bamboo and leather box that a Kumaoni bride would traditionally carry to her husband’s home after marriage. In present times, a Beoli Pitara has been replaced by factory-made bags and briefcases during local weddings.

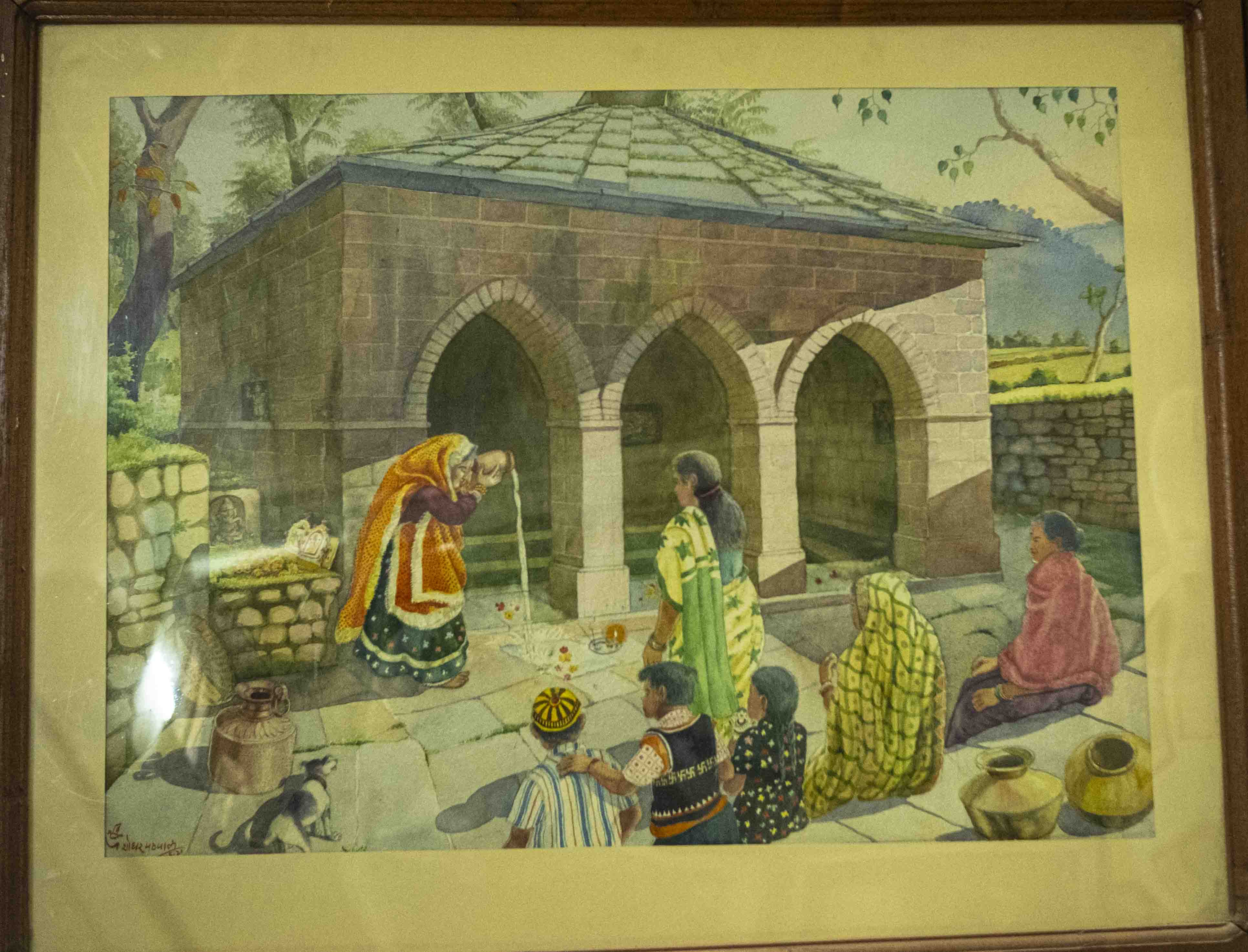

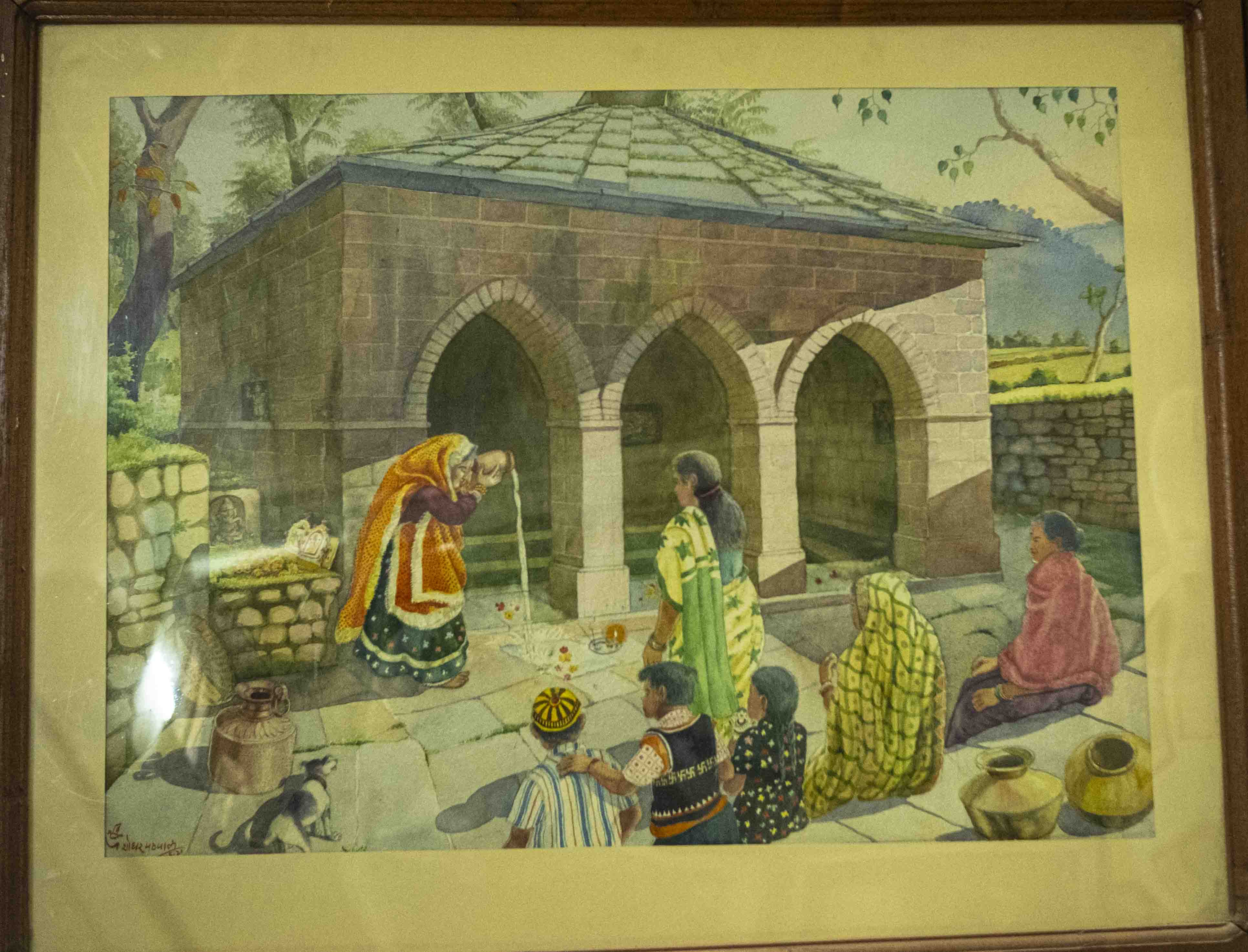

On the first floor, more than 500 of Dr Mathpal’s original artworks adorn the walls of the corridors. It also houses a versatile collection of stunning watercolour and other mixed media artworks, which often brings the onlookers closer to the everyday life of the natives of the hills of Uttarakhand. There are scenes of a slow village life on the canvases, often with a recurrent focus on the rigorous working conditions of women in the hills. The subjects of these paintings are sometimes a miller inside a Gharat, a traditional water mill, or a newly-wed bride offering prayer at a Naula, a community groundwater spring.

“Why do we paint? Why do we indulge in any artistic endeavour? This has been my query from the very beginning,” said Dr Yashodhar Mathpal. In 1973, he was a young artist, drawn to the findings at Bhimbetka in Madhya Pradesh. On a whim, he set out to Pune to conduct research work from Deccan College on the topic. In the years to come, he studied the drawing materials, motivations, and historical contexts of the 133 cave art sites in the region. At Bhimbetka, he completed 400 compositions, copying almost 6214 cave paintings, exactly to scale. Scholars and experts worldwide took note of his exhaustive and seminal work, Prehistoric Rock Paintings of Bhimbetka. These paintings, acquired by the Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts in New Delhi, now feature in IGNCA’s cultural archive.

In 1983, he purchased a 5-acre hillside for the museum in Khutani, Bhimtal. He chose this location for its proximity to the tourist towns of Nainital and Bhimtal, in the hope of attracting visitors. For Rs 4000, he bought a barren slope covered with invasive lantana bushes. Everything he had from his savings to research grants and proceeds from the sale of his paintings, he put to use to fund the process.

In the first year, a 24×36 feet hall was partly used as a residence and partly as a gallery. It took four years and a prolonged legal battle for water and electricity to reach the museum campus. In the forty years since, the wild hill slope has transformed into a thriving mixed forest with over 300 species of plants and trees, and three dedicated galleries for the museum and Dr Mathpal’s artwork.

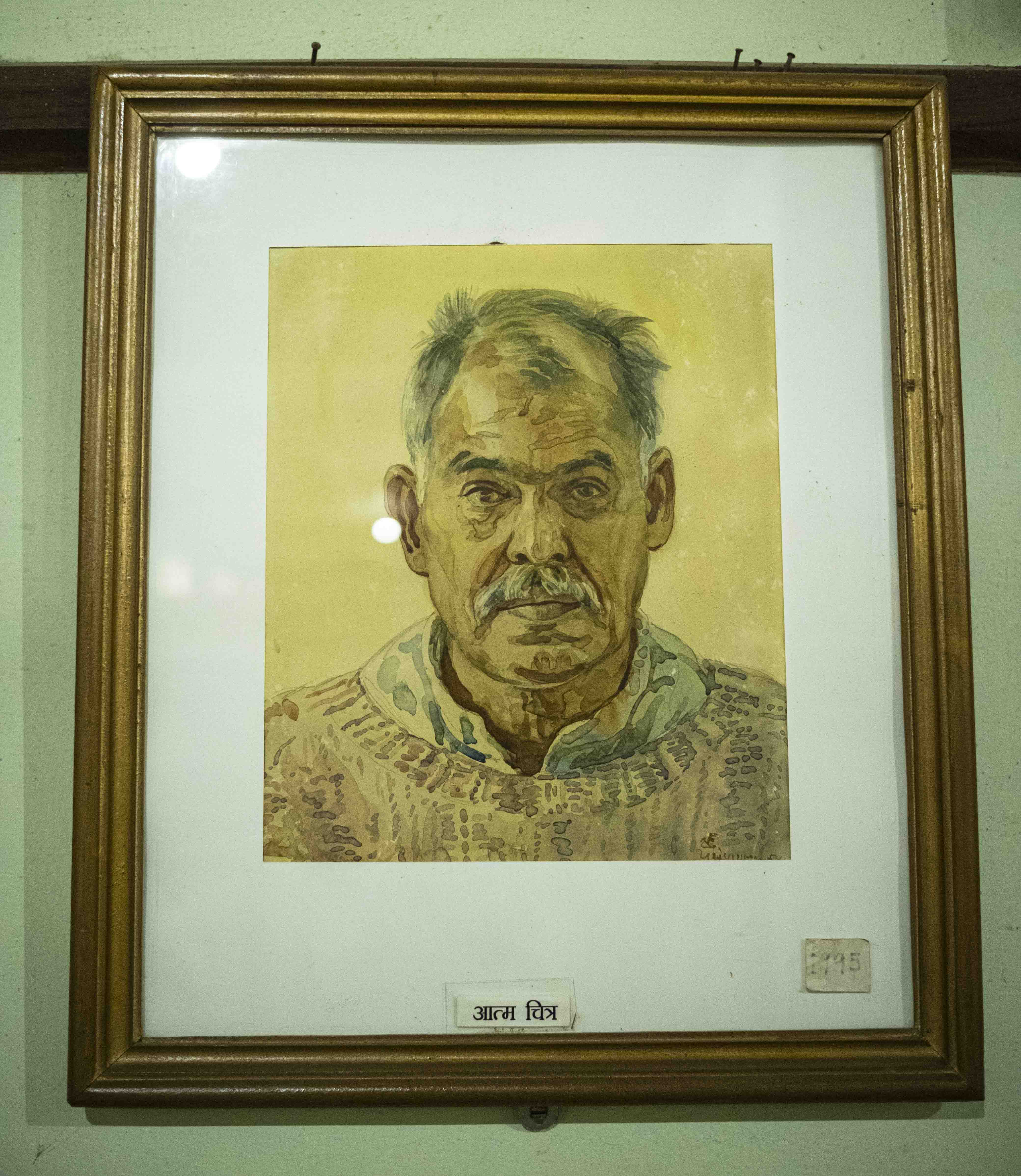

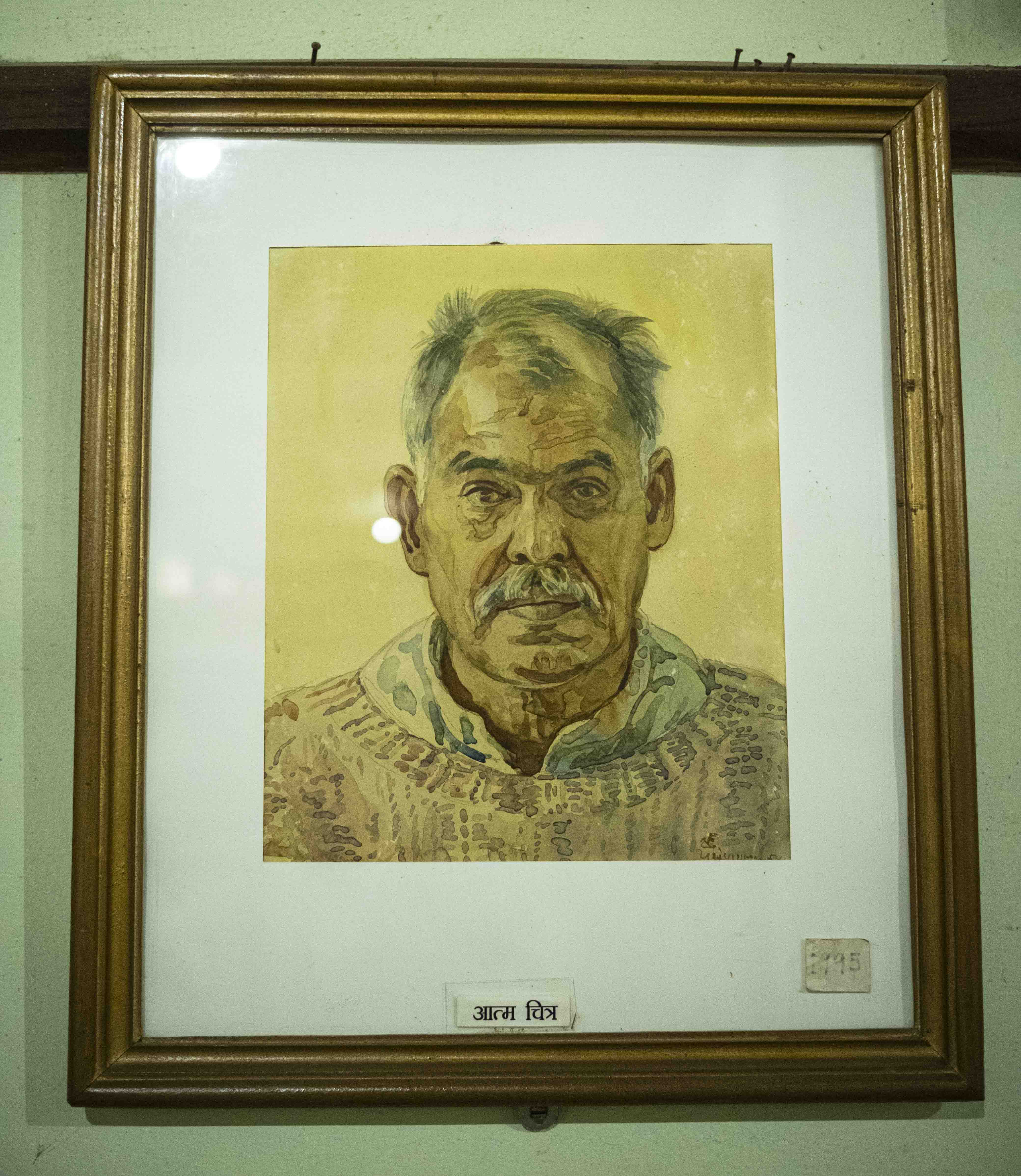

The museum houses a traditional Kumaoni restored woodwork facade from his own ancestral home in Naula village, in Almora district. At the reception of the museum, hangs a portrait of his Gandhian father. Looking at it, he quipped, “He still looks angry at me. He never agreed to my plans of pursuing the arts. I might look like my father, but my value system stems from my mother.”

He talks about his freedom-fighter father, who prioritised his public life over a personal one. He went to jail during the independence struggle, but never accepted any benefits for it while he was alive. Neither did he ever offer any help to his children, and donated his last ring to the National Defence Fund during the Indo-China War.

“…But if I had to vote, I’d vote for her,” he said about his mother, who he remembers helming the endless chores of running a household single-handedly, working in the fields, growing food, mending the walls of the fields washed down during the rain, and living simply.

As a child, he would go with his mother to the banks of the Ramganga to collect stones.

After all these years, his collection has expanded manifold. However, four decades into the project, the museum continues to operate with the help of just a single staff member. The collection lacks a digital archive, and with every passing year, humidity and a damaged roof are taking a toll on the paintings and antiquities on display.

At the age of 86, Dr Mathpal spends each day painting and reading the Bhagavad Gita. It was perhaps this simplicity that made it easier for him to work with several communities living at the absolute fringes of the social system and commemorate their version of a sustainable life.

Related Posts

What’s Lost and What’s Left Behind Amidst the Migration Woes of Uttarakhand: Preserving the Heritage

In the hill state of Uttarakhand, the Tharu tribe is the most populous tribal community, constituting 0.8% of the state’s population. The Tharus have historically lived on both sides of the Indo-Nepal border in Uttarakhand, Uttar Pradesh, and Bihar. In Uttarakhand, they reside in the Terai lowlands, which, unlike the steep Himalayan hill districts, offer flat terrain, fertile land, road and rail links to the plains, and proximity to major markets in UP and Delhi. This made Terai a key area of developmental extraction and rapid industrialization for the state.

The establishment of the State Infrastructure and Industrial Development Corporation of Uttarakhand Ltd (SIIDCUL) after 2002 in the Terai region led to rapid land acquisition by industries, affecting the habitation of the indigenous Tharu population. Faced with depleting grasslands and the difficulty of assimilating with the new developments, the tribe’s traditions, lifestyle, and rich weaving culture have undergone gradual erosion.

They have traditionally worshipped the land goddess, Bhumsen, and nurtured an ecologically harmonious lifestyle. Sourcing cordgrass, or kaas, from the tall grasslands, as well as other readily available materials, the community developed a sophisticated weaving culture that was passed down through the generations. Grass is collected before the monsoon, and left to dry till the end of the season, when the blades become pliable for weaving.

The Tharus used these woven baskets to store grains, clothes, and also for traditional cooking. Colourful baskets made by interweaving feathers and wool were used for gifting during traditional marriage ceremonies. A rapid lifestyle shift in the region and outward migration of the tribal population make these traditional Tharu baskets a rare commodity.

The issue of outward migration remains untackled in a state that was formed 25 years ago, with the vision of supposed ecologically sustainable development in the hills. The tribes from the hill regions, namely Bhotia, Jaunsari, and Raji, as listed by the Tribal Research Institute, Uttarakhand, migrate to the nearby towns and cities in the plains for better opportunities, education, and healthcare.

Migration has surged in the last few decades due to historic government neglect: a lack of connectivity to remote mountain villages, to basic education, healthcare, and employment opportunities. Climate change, compounded by conditions such as uncertain monsoon patterns in these ecologically sensitive mountain regions, makes agriculture a difficult choice. There is also woefully inadequate government assistance in horticulture or agriculture, leaving farmers to fend for themselves.

Prospects are also grim for the nomadic pastoral community of the Van Gujjars in Uttarakhand, who are primarily Muslims. They move between mountain pastures, or bugyals, in the summer and the lowlands during winter. From March to May, these forest dwellers battle for survival amidst forest fires, and during the monsoon, they face increasing losses of livestock due to floods.

The community is not just at the forefront of the climate crisis, but also vulnerable to the right-wing policy makers in the state. Eviction notices were served to 400 Van Gujjar households in May 2023, alleging encroachment of government land. Amidst theories of ‘Land Jihad’ floated by the BJP state government, the Muslim Van Gujjar community is scrambling to piece together the proofs of their native nomadic identity in the state.

The Devastating Impact of Outward Migration

Research published in the South Eastern European Journal of Public Health suggests that Pauri Garhwal, Bageshwar, and Uttarkashi are the worst-affected districts by migration woes in Uttarakhand. Each year, new ghost villages in Uttarakhand are documented with zero population in official studies and reports.

Semla, in Tehri District, a village comprising almost 50 households a few decades ago, now has a population of less than 10. Jhakot village in Pauri district is also abandoned, with all seven resident families having migrated to bigger nearby towns. Godi, in Kotdwar, is one of the many villages vacated due to human-wildlife conflict in recent times.

Partially abandoned villages are often gradually overtaken by wilderness, resulting in attacks by leopards and other wild animals, which pose a persistent threat to the remaining residents. After facing repeated destruction of crops by wild boars, monkeys, and other stray animals, locals often resort to abandoning their ancestral agricultural lands.

Through the last 25 years, loopholes in land laws have been exploited by the state to allow mass-scale land deals for resorts, wellness centres, and high-end private properties in eco-sensitive zones. In January 2025, for example, an incident of illegal tree-felling and the unauthorised use of heavy digging machinery for the construction of a resort surfaced in the Khairkhal Laldhang Forest Range.

26 trees were cut at the site, when permission granted by the forest department was for only 14 trees. Felled trees include Khair trees, which come under the protected category. Here, the revenue inspector had to visit the site and intervene three times before the work could finally stop.

Locals also allegedly accused the Tehsil Administration of negligence due to the influence of former Revenue Minister Prem Chand Aggarwal, whose son, Piyush Aggarwal, owns the project. Laldhang range officer (DFO) has now filed a case against Piyush for the illegal felling of trees. These remote eco-sensitive areas are prime properties, where encroachment and illegal construction in forest areas often go unchecked.

According to a report by The Print, until February 2025, non-locals were allowed to buy up to 12.5 acres of agricultural land in the state, with provisions to increase it. It was only after the public outcry for ‘Sashakt Bhoo Kanoon‘ or strict land laws that an amendment was enacted, placing a blanket ban on the purchase of agricultural and horticultural lands by non-locals, excluding only the lowland districts of Haridwar and Udham Singh Nagar. The measures were taken, according to CM Pushkar Singh Dhami, ‘to protect the state’s resources, cultural heritage and citizens’ rights.’

How this amended law is enforced is yet to be seen; however, many locals believe that irreparable damage has already been done to the hills with lakhs of hectares of forest and agricultural land lost due to encroachment and illegal construction. In more than 1700 of Uttarakhand’s remote ghost villages, elderly parents are often the last settlers left.

What’s lost in these empty villages is entire communities themselves, not to mention a thriving agrarian culture and the community’s inherent knowledge to live harmoniously with the fragile ecosystem around them. Festivals and rituals, often centred around their ancestral villages and land deities, gradually vanish to cultural assimilation and globalization, as do traditional medicines, dyeing techniques, woodwork, weaving techniques, and cuisine.

Preserving the Heritage

The task of preserving the tangible and intangible heritage of a place and community is a multifaceted process, primarily overseen by the Ministry of Culture. The Archaeological Survey of India (ASI), under the Ministry of Culture, also runs 52 site museums across India and has recently been the subject of controversy over its resource allocation. According to data presented in the parliament, 25% of ASI’s total budget was allocated to the state of PM Modi’s Gujarat between 2020 and 2025.

Further, out of the 8.5 crore spent in Gujarat, 8 crore (94%) was spent solely in Vadnagar, Prime Minister Modi’s hometown. During the ongoing excavations, ASI uncovered a settlement in Vadnagar dating back to 800 BC. A joint study by ASI and IIT Kharagpur was conducted that revealed the evidence of ‘cultural continuity’ in Vadnagar, Gujarat, after the collapse of the Harappan civilization, challenging the notion of a Dark Age in Indian history. At Vadnagar, a state-of-the-art, India’s largest archeological excavation experiential museum has also been built.

There are 38 museums in Uttarakhand listed on the Ministry’s official website. Of these, 18 operate under the Central government, 6 under the state government, and 14 others are run privately or by non-governmental organisations. The Lok Sanskriti Sangrahalay is one such privately run museum, founded by Dr Yashodhar Mathpal, a renowned artist, curator, and scholar whose study of Rock Art paintings in Bhimbetka is one of the most comprehensive research studies on India’s oldest prehistoric rock art site.

As an artist and curator, he worked with the Government of India to establish museums in Kerala and Central India. His vision to preserve the heritage of his land led him to set up Lok Sanskriti Sangrahalay in Uttarakhand in 1983.

Aware of the systemic corruption, Dr Mathpal has been a crusader for the preservation of the heritage of the people of Uttarakhand. Climate change, illegal land acquisition, demographic changes, cultural assimilation, and the government’s systemic negligence– the threats are manifold. The Padma Shri awardee understands these threats of erasure that loom over the indigenous communities.

However, his primary focus for four decades has been on what can be saved from these abandoned villages, locked homes, and fields left behind by the ones who migrated. He has meticulously documented and exhibited the clothes, utensils, and objects of everyday use of all major tribes and communities of Uttarakhand at his museum.

Politicians and local authorities have repeatedly announced grants for the upkeep of the museum during political rallies and meetings, but no such funds were ever released to him. He was appointed the Vice President of the Literary and Cultural Council of Uttarakhand in 2005. He resigned a year later, citing deeply entrenched corruption in the bureaucratic system that misallocated or inflated budgets meant to support artists and cultural institutions. Despite no government aid, he has nurtured the Folk Cultural Museum as a space that helps piece together the identity of the people who have historically called these hills their home.

In archaeological terms, any man-made object more than 100 years old, or documents of relevance as old as 75 years, can be termed as ‘antiquity’, and this museum is replete with them. Since the museum’s inception, Dr Mathpal has appealed to locals and visitors to donate old utensils, agricultural equipment, land records, documents, and the smallest of objects that might be relevant to the past. At the museum, his carefully curated collection features antiquities acquired from local households, such as a 6th-century land record known as Badua Kagaz. And sometimes objects are unearthed from surrounding ravines and lakes, like weaponry from the Revolt of 1857 and agricultural equipment that is more than a century old.

Folk Cultural Museum

On the shelves at the museum are neatly placed traditional firestarters, baskets made of dry gourds, locally made paper, ink, combs, and traditional weighing cups called ser and mana. Bonda, Tauli, Bhaddu, all cooking utensils of yesteryear, made of brass, bronze, and ashtadhatu, or the eight metals once used by the people of these hills, are on display. On the corner shelf sits a Beoli Pitara, a 300-year-old bamboo and leather box that a Kumaoni bride would traditionally carry to her husband’s home after marriage. In present times, a Beoli Pitara has been replaced by factory-made bags and briefcases during local weddings.

On the first floor, more than 500 of Dr Mathpal’s original artworks adorn the walls of the corridors. It also houses a versatile collection of stunning watercolour and other mixed media artworks, which often brings the onlookers closer to the everyday life of the natives of the hills of Uttarakhand. There are scenes of a slow village life on the canvases, often with a recurrent focus on the rigorous working conditions of women in the hills. The subjects of these paintings are sometimes a miller inside a Gharat, a traditional water mill, or a newly-wed bride offering prayer at a Naula, a community groundwater spring.

“Why do we paint? Why do we indulge in any artistic endeavour? This has been my query from the very beginning,” said Dr Yashodhar Mathpal. In 1973, he was a young artist, drawn to the findings at Bhimbetka in Madhya Pradesh. On a whim, he set out to Pune to conduct research work from Deccan College on the topic. In the years to come, he studied the drawing materials, motivations, and historical contexts of the 133 cave art sites in the region. At Bhimbetka, he completed 400 compositions, copying almost 6214 cave paintings, exactly to scale. Scholars and experts worldwide took note of his exhaustive and seminal work, Prehistoric Rock Paintings of Bhimbetka. These paintings, acquired by the Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts in New Delhi, now feature in IGNCA’s cultural archive.

In 1983, he purchased a 5-acre hillside for the museum in Khutani, Bhimtal. He chose this location for its proximity to the tourist towns of Nainital and Bhimtal, in the hope of attracting visitors. For Rs 4000, he bought a barren slope covered with invasive lantana bushes. Everything he had from his savings to research grants and proceeds from the sale of his paintings, he put to use to fund the process.

In the first year, a 24×36 feet hall was partly used as a residence and partly as a gallery. It took four years and a prolonged legal battle for water and electricity to reach the museum campus. In the forty years since, the wild hill slope has transformed into a thriving mixed forest with over 300 species of plants and trees, and three dedicated galleries for the museum and Dr Mathpal’s artwork.

The museum houses a traditional Kumaoni restored woodwork facade from his own ancestral home in Naula village, in Almora district. At the reception of the museum, hangs a portrait of his Gandhian father. Looking at it, he quipped, “He still looks angry at me. He never agreed to my plans of pursuing the arts. I might look like my father, but my value system stems from my mother.”

He talks about his freedom-fighter father, who prioritised his public life over a personal one. He went to jail during the independence struggle, but never accepted any benefits for it while he was alive. Neither did he ever offer any help to his children, and donated his last ring to the National Defence Fund during the Indo-China War.

“…But if I had to vote, I’d vote for her,” he said about his mother, who he remembers helming the endless chores of running a household single-handedly, working in the fields, growing food, mending the walls of the fields washed down during the rain, and living simply.

As a child, he would go with his mother to the banks of the Ramganga to collect stones.

After all these years, his collection has expanded manifold. However, four decades into the project, the museum continues to operate with the help of just a single staff member. The collection lacks a digital archive, and with every passing year, humidity and a damaged roof are taking a toll on the paintings and antiquities on display.

At the age of 86, Dr Mathpal spends each day painting and reading the Bhagavad Gita. It was perhaps this simplicity that made it easier for him to work with several communities living at the absolute fringes of the social system and commemorate their version of a sustainable life.

SUPPORT US

We like bringing the stories that don’t get told to you. For that, we need your support. However small, we would appreciate it.