The COVID-19 pandemic brought to the fore lasting structural fragilities and inequalities: An analysis of the situation is Southern Italy

“Here we survive, we rig-up, we try to move on, in every way we can. It’s already difficult for us to make it to the end of the day, can you imagine what it’s like after three months with no income?” asks Salvatore, 50, as he takes long puffs from a cigarette, filling the air of his living-room with thick smoke. A father of five, he has worked all possible jobs, all of them in the informal sector, since he left school aged 7. Without a formal contract or social security, his name is nowhere to be found in the employment databases. He has done everything to make ends meet: plumber, carpenter, tailor, electrician, mechanic. Before the lockdown, his daily-wage work as a bricklayer was barely enough to put bread on the table. When the lockdown was imposed following the COVID-19 outbreak, his life-line got interrupted and, with no savings at hand, he experienced the hardest time in his life. “We are used to suffering, but this was worse,” he says with a mix of shame and resignation. For many in Southern Italy, the lockdown turned out to be a crisis within the crisis that mainly affected vulnerable and marginalized groups as well as informal workers.

Streets are usually packed and loud in Naples, where life’s hustle and bustle are the main feature of Southern Italy’s biggest city. Laid at the foot of one of the most dangerous volcanos in the world – the majestic Vesuvius, a sleepy giant and yet a constant threat to the inhabitants – the city leans on a tuff halfmoon that encircles the Gulf of Naples, right at the center of the Mediterranean Sea. A crossroad of cultures, Naples fulfils the stereotypes it is associated with: noisy, frantic, dirty. Its old center is a maze of dark alleys separated by wide avenues paved during the “rehabilitation” – the urban regeneration carried out during the unification of Italy and after the cholera epidemics. It is a restless hive of activities with its busy markets, its smells and sounds. During the lockdown days, however, the stillness and silence that reigned in the streets felt unreal – it was as if someone had pressed the pause button.

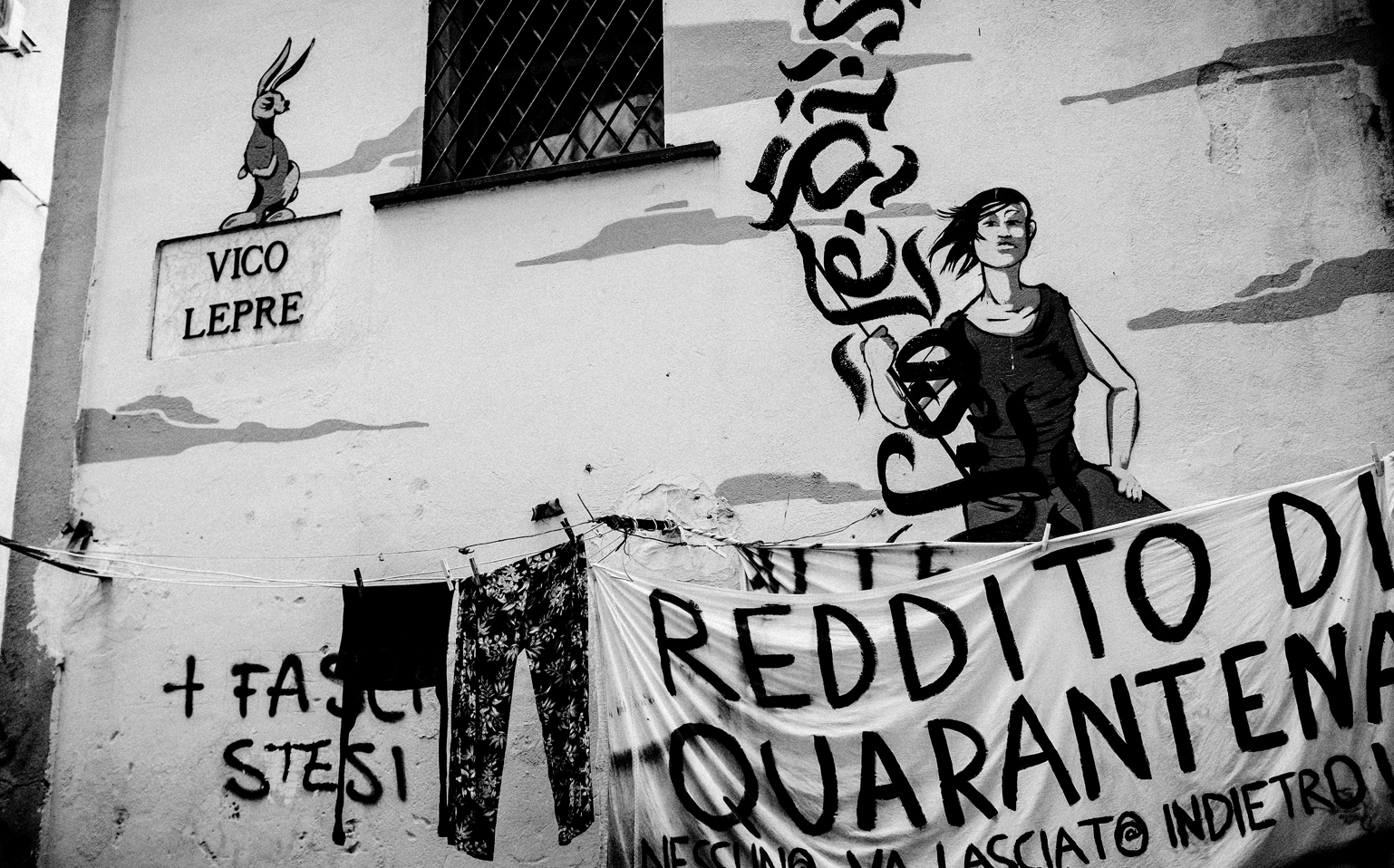

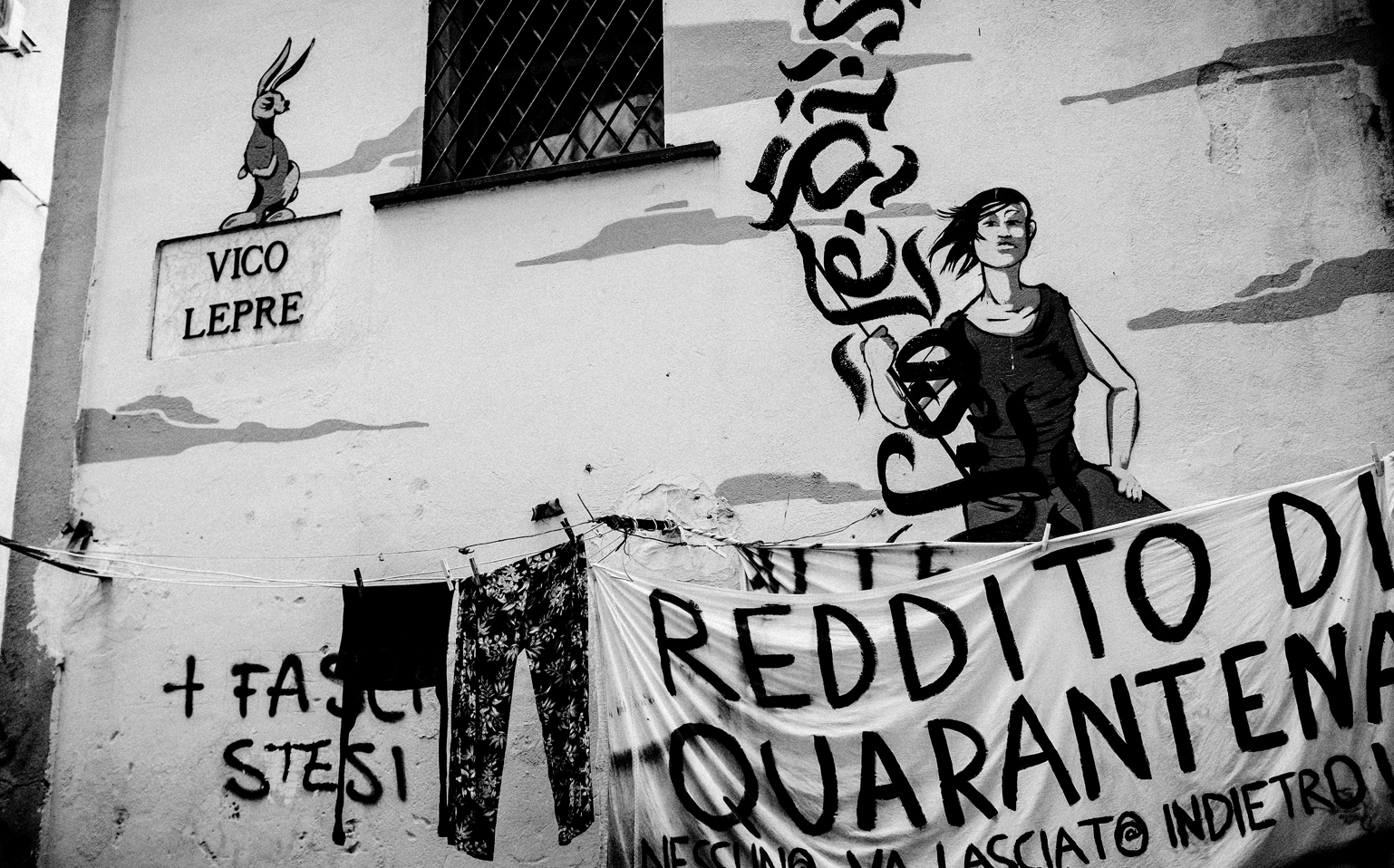

Despite a propension towards chaos, a bad reputation as rule-breakers and a lower diffusion of the virus compared to the wealthier Northern Italian regions, people in Naples have been strict in obeying the nation-wide lockdown imposed in mid-March in an attempt to curb the spread of the disease. The usually crowded and teeming streets now emptied of people and life had something sinister. People would lean out of the window in despair, as if they were waiting for something to happen – like prisoners waiting for their release. Policemen were deployed at every corner to check on the compliance with the ever-changing Prime Minister’s decrees that, piece by piece, eroded personal freedoms in the name of public health.

After quarantining two “red zones” in Northern Italy, as coronavirus kept spreading, in early March the government imposed draconian containment measures across the country. In the Northern regions – the epicenter of the contagion accounting for most of the cases – the pandemic overwhelmed what was believed to be one of Italy’s most efficient health care systems, which are funded by the State but administered at the regional level. While the socio-economic divide between North and South is rooted in history and stems from structural and infrastructural differences, the pandemic and the longest lockdown in Europe exacerbated it. The North is the economic engine of the country and, even though COVID-19 decimated an entire generation, for the sake of saving the economy many factories never came to a real halt thus helping the virus spread. In Lombardy, the region where Milan is located, the mortality rate was among the highest in the world. It was feared, however, that in the poorer and lesser industrialized South the virus would wreak havoc to the already fragile healthcare system and that the effects of the economic crisis triggered by the lockdown would be more intense and will have deeper consequences. Here people are used to expedients to survive and, as expected, the repercussions for those who were already at the margins of society have been devastating. The pandemic disrupted their fragile survival mechanisms making social inequalities even starker, thus creating new marginalities.

Hidden in the winding lanes of Montesanto district in Naples, there is a two-story building known as Sgarrupato(“crumbling” in the local dialect) where volunteers from the Spazio DAMM and the activism and resistance movement 7 Novembre provided food to some 350 families who were struggling to make ends meet during the lockdown. Maria, wearing mask and gloves, is packing bottles of tomato sauce and other essentials to be distributed in the adjoining Quartieri Spagnoli. “We are unemployed ourselves, but we try to help those who are in need. As public institutions are absent and the parameters to access food stamps are so strict, many people are cut out,” she says as other volunteers gather outside the building to distribute grocery bags to an ever-growing list of families in need. From a small volunteering activity, this grassroots food distribution grew to become a fully-fledged assistance service that helped contain the emergency as well as the risk of criminal infiltrations in the gaps left by the State. The solidarity net in Naples in fact reached a capillarity and efficiency that went way beyond the institutional one. “Many self-managed mutualism networks have come together in these difficult times. They are partly made up of political activists, but also lots of people from civil society, from the singer to the mechanic, to the taxi driver who is currently not working,” explains Alfonso De Vito, who is part of a local housing rights movement. These grassroots mutualism networks – made of too many organizations to name them all – have helped some 2,000 families get by. “This cross-section of society is the most beautiful part of this terrible story – says De Vito – but this narrative cannot be an alibi for the institutions not taking responsibilities.”

With unemployment rates three times higher in the South than in the North and a strong incidence of irregular work, the cash shortage and the bureaucratic slowness of economic aid packages made the risk of social tensions in Southern Italy a concrete perspective. Early into the lockdown, intelligence agencies warned the authorities of “a potential danger of spontaneous and organized riots and rebellions” in the South: due to cash shortage, many families were struggling to fetch a meal, pay the rent and fulfill the most basic needs. “In Naples and its metropolitan area there are segments of the population who live off daily subsistence. In the lockdown phase, this type of economy disappeared completely: people went from an income of 20 euros per day [22 USD], to null. The people working in this segment are the most vulnerable because they cannot benefit from any social safety-net or public welfare,” explains Prefect of Naples Marco Valentini. With government emergency aid packages reaching late and only a fraction of the needy, it was solidarity and mutualism to help people cope with the most immediate need of the crisis: hunger. The city’s response to the socio-economic emergency was an incredibly efficient network of self-organized collectives that provided families with low or no income with groceries and homeless people with a hot meal. This social lifeline was the product of volunteering and grassroots donations.

Besides secular and Catholic organizations, there was also an effective collaboration with the Buddhist and Senegalese communities. Many private citizens also set up to prepare and distribute food to those who could not abide by the rule of #iorestoacasa (I stay home). At noon in Piazza Mercato, a long, ordered queue slithers from the Mensa dei Poveri (soup kitchen). “We are the angels of the epidemic,” says Father Francesco, while Stefano, a yoga teacher, and other volunteers from Responsabilità Popolare are preparing food in the canteen next to the Basilica del Carmine. When the lockdown was announced, many homeless shelters – including showers and lockers – and soup kitchens were shut down out of sanitary concerns. “Before the pandemic, we used to distribute around 150 meals a day, now we prepare 700,” says the Carmelite Father in a rare pause from the fervid kitchen activity. “Food is not a problem, we can manage, but for many it is impossible to follow the basic hygiene rules: it is a sanitary emergency.” Many have resorted to washing in the subway’s toilets. It is an army of people sharing old and new vulnerabilities: homeless, migrants, clochards, but also people made poor by the pandemic. These days, poverty is spreading at a fast pace in different segments of society.

Among the groups relying on food aid there are also the so-called “new poor.” In a situation where marginalities are overlapping and piling up, the lack of cash put many families at risk of losing the roof over their head. Many tenants never formally signed a lease: a widespread malpractice encouraged by owners themselves in order to avoid taxation. Residents without a regular contract were not able to access rent aid measures and are now in danger of losing their homes. “We are falling into a much poorer economy. The risk is that after the health pandemic, there will be an evictions’ pandemic,” warns De Vito from the housing rights movement. “The economy has come to a halt and so has the income for many people. How will they pay the rent when the aid is over?” More than 64,000 rent aid requests were filed in Campania (the region where Naples is located), while 10,000 are the eviction procedures in place and many more are expected later in the year. Three months of cash flow crunch have taken a heavy toll on the population and on the economy. The fear is that criminal organizations could profit from the economic discomfort many families – and businesses – are presently faced with.

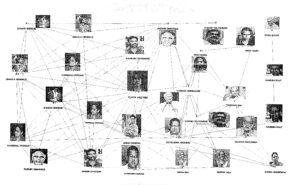

Camorra –the organized crime syndicate from the region of Campania and one of the different mafias that exist in Italy like the ‘Ndrangheta in Calabria, the Sacra Corona Unita in Puglia and Cosa Nostra in Sicily – is a complex organized crime phenomenon whose history goes back to the 19th Century. Until the 1980s, the Camorra was mainly focused on controlling the territory through racketeering, prostitution, weapons and cigarette smuggling. Since then, the Camorra has also acquired a significant presence in other European countries due to its role in international drug trafficking. With the 1980 earthquake in Irpinia, the Camorra began to meddle with public funds for reconstruction: the new business consisted in setting up construction enterprises, and then influencing policies by guaranteeing support and bribes to local politicians in exchange for tenders. From the 1980s onwards, the Camorra went transnational – making use of the deregulation imposed by the globalization – making huge illegal profits that constantly need to be re-invested and laundered. Public administrations are also exposed to criminal infiltrations as the aim of the mafias is to manage and convey public money on activities which are relevant to their scope.

Monitoring the many ways in which organized crime adapts to changing conditions is a real priority in a city like Naples. “Here, the risk of criminal infiltrations is a very sensitive issue due to the significant presence of organized crime. Our first worry is to prevent organized crime from providing criminal welfare,” explains Prefect Marco Valentini. “There are ongoing investigations on the role that the Camorra tried to play during the lockdown phase, particularly in the provision of food aid to families in need,” he asserts. Yet, according to the Prefect, the current post-lockdown phase is the most delicate. In terms of prevention, authorities are implementing a number of measures in view of the economic restart in September, considered a critical date. “Since organized crime has considerable cash, it is possible that through new and old usury mechanisms – not only loans but also donations – criminal organizations may take advantage of the difficult situation that small businesses and companies are facing.”

The lockdown costed the Italian economy 47 billion Euro (52 billion USD) each month, 10 of which in the South. Svimez, a non-profit organization promoting the study of South Italy’s economy, foresees that in 2020 the country will face a Gross Domestic Product (GDP) contraction of 9.3 percent: 9.6 percent in the Centre-North and 8.2 percent in the South. A recent study by the same non-profit shows that the North-South economic divide will further deepen during this year: while the costs of the lockdown and the GPD collapse will be heavier in the Northern regions, the Center-North of the country will lose 600,000 jobs and the South 380,000. Hence, the latter – already in recession before the pandemic – will proportionally suffer the greatest impact of the crisis in terms of occupation and its growth will be halved by next year. In the Southern regions there are also the highest rates of poverty and shadow economy, according to data by the national statistical institute. Families living in relative poverty are estimated at just over three million, with the Southern regions of Calabria, Campania and Sicily registering the highest incidence. Shadow economy and informal work are also more present in the South than in the North: Calabria is the region where the weight of the underground and illegal economy is the greatest, with 20.9 per cent of the total added value, followed by Campania and Sicily. In those segments, money has stopped circulating, hence a part of the population has stopped spending.

In July 2020, two months after the lockdown has been lifted, streets in Naples are again bustling with people: as life seems to flow back city’s veins, the emergency is far from over. Even though streets are busy again, it is clear that business is not fully back yet. Many restaurants and shops have not lifted their shutters and the cash crisis is palpable. “We have a 50 percent drop in the sales of Margherita pizzas,” states Coldiretti, the association of food producers. “We work mainly with takeaway, but tables are empty,” explains Antonio Improta from Pizzera 22 in the Pignasecca district, one of the oldest open-air market of the city of Naples. “The distance between tables imposed by the institutions has more than halved the seats. Due to the economic crisis, many people prefer to do without eating out.” In a city where restaurants were usually always full, and dining out is reasonably cheap, it is unusual to see them so empty. As pizza consumption acts as a market indicator, numerous restaurants, bars, clothing stores and other activities are also gasping for air. The collapse of pizza sale is a significant warning for a city like Naples: the drastic downsizing of its market is the mirror of a “post-war” economy.

The battle against the virus has often been compared to a war, as if the word pandemic were not enough telling of the emergency many countries have experienced. In the current post-lockdown phase, many analysts are setting parallels with the 1945 post-World War II recovery. The frequent reference to post-war times in the media – despite the obvious differences – has a self-delusional function aimed at encouraging the population and boosting national unity. Yet, while in post-war economy the demand could not find a corresponding offer, the opposite is happening today: goods on offer are available, but there is little cash and even less will to spend it. The fear is that, in an era that has witnessed an unprecedented interconnection and globalization, it will take much longer than in post-war times for economies to recover. United Nations Secretary-General Antonio Guterres said that the “economic impact will bring a recession that probably has no parallel in the recent past.” The shock effect of the COVID-19 emergency also revealed all the flaws and injustices of our societies, worldwide.

In Italy, the economic system runs on two-speeds with the country spit in two: North and South of Rome, the national capital. The lockdown plunged Southern Italy’s absolutely precarious economies into a deep crisis. “Given a widespread cash problem,” says Luigi Cuomo, racketeering expert at Libera, an association working against mafias “today there is both a strong demand and an equally strong supply of loans by organized crime. The reopening [of activities after the lockdown] prompted the need for cash, but the Italian banking system is among the most obtuse and medieval banking systems in Europe. The failure in granting legal credit allows illegal, criminal credit to flourish,” he continues. The Mafia – a term originally associated with the Sicilian Mafia, now often used collectively to include all regional criminal outfits – lends money not only to grow its capital but also to infiltrate legal businesses to launder its own capitals. “All usurers are criminals, but Mafia’s usury is growing at a concerning pace in recent years – explains Cuomo – it not only produces income, but it also infiltrates businesses: it launders illicit capital by putting it back into the legal market, it ousts troubled entrepreneurs by first taking control of the company and then of its ownership.”

The Prefecture of Naples is closely observing the phenomenon. “We are constantly monitoring changes in shareholder structure, or company transfers, or branches of it,” says Prefect Valentini. “Stock markets and transfers are a spy: if data is anomalous it leads to suspicion of a criminal intervention aimed at influencing the life of that company.” Even more than any other business, mafias observe the market trends and adapt to the changing context. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the Camorra also reinvented itself in new sectors: the most important is the business of PPE [Personal Protective Equipment], such as the production of gowns and masks, says Valentini. However, usury is the first resort for an activity in crisis. Usury is also an effective money-laundering mechanism: the social emergency caused by the coronavirus has been a great opportunity in this sense. “By lending money, they [the criminal cartels] risk very little and have huge returns. Today they do not even need to coerce people into their illegal money-lending schemes, victims are already flocking towards them. At first sight, the usurer appears as a comforting figure, the one that comes to help you – says Cuomo – a honeymoon that in some cases can last long, in other cases less. Only then, victims will begin to seek help and report.”

It is too early now to assess the impact of usury during the COVID-19 pandemic, according to former racket victim and judicial witness Luigi Ferrucci, President of the Italian Federation of anti-racket and anti-usury associations (FAI), figures will emerge in the long run. In the last two months the Prefecture of Naples has received 26 reports from entrepreneurs who stood up to oppose criminal harassment and have faced increasing difficulties to reintegrate their companies into the healthy productive fabric of the country. “People who fall into money lending schemes take time before they ask for help. We have introduced a new tool, an online listening desk that allows victims to get in touch with us and talk to our experts. We have to be attentive in detecting new dynamics and this can be done only at the grassroots level.” According to Libera’s Cuomo, the State must think of new loan models, not necessarily through the banking system, “whose strict and inaccessible credit regulations make [the banks] victims of their past mistakes,” he explains, “It is necessary to allow private individuals to lend money [in a regulated manner] in competition with banks, so as to trigger a virtuous mechanism and annihilate usury.”

Time is crucial in this context. “The State must act before Mafia does,” urges Rosario Stornaiuolo of the consumers’ association Federconsumatori. “European aid packages must reach small entrepreneurs before the Camorra lends them money first and then usurps their companies, thus also benefitting from public aid.” It is a call for de-bureaucratization in a country where procedures are often lengthy and complex. Camorra is no longer the same as in the 1970s or 1980s, it has evolved both in scope and reach. “Today it is entrepreneurial, it is run by white-collar, educated people who are able to understand these mechanisms.” Food catering and tourism are the main sectors under observation in Naples after the COVID emergency. “Before COVID, these were driving sectors of the city’s economy,” recalls the Prefect Valentini, “Especially in recent years, Naples witnessed an exponential increase in tourism: these sectors are the most exposed now.” The city center, until recently turned into a touristic amusement park, is spectral these days: all activities related to the tourism business are suffering a lack of customers and are at risk of going bust and could hence easily become targets of criminal infiltrations.

Unlike other entrepreneurial actors, Camorra seems to have an infinite availability of cash that needs to be pulled back into the market. Camorra, though, like every other business, has suffered from the current crisis: its supply chain was partially disrupted and experts agree that usury is the only upward activity to produce hegemony in this context. “We believe the lockdown affected also the criminal economy,” says Libera’s Fabio Giuliani. The lower segments of the drug trade – the open-air drug-dealing markets – and their relative profits suddenly dropped. Fabio Giuliani explains that “the drug-dealing outposts where users buys drugs from local criminal cartels have suffered significant losses, to such an extent that the demands for methadone by people who could not fetch their doses during the lockdown has significantly increased.” Despite the losses, the Camorra is the only big player in the market economy that still has cash availability in a time of recession. “In some districts in Naples the criminal cartels have distributed food aid and handed out money, from 50 to 500 Euro,” explains Fabio Giuliani. “A parastatal welfare aimed at building consensus in a specific territory, Camorra knows how to build strong ties and a solid economy.”

In this unfolding crisis, the mafias are trying to increase their hegemony. Prevention seems to be entrusted entirely to civil society associations engaged in providing assistance against usury. These civic networks represent a great moral asset, but they are certainly not enough at an operational level. “Associations and cooperatives against the mafias are experiencing a great crisis,” admits Fabio Giuliani. “It seems that there are always other priorities. Today, the top priority is revitalizing the economy at any cost. During the lockdown, it was the civil society to keep the boat afloat. The focus is now on recovery, while the social network that has proven crucial during the crisis has been placed on the back burner. Today,” warns Giuliani “Camorra has an even greater infiltration capacity compared to the 1980s,” the years of its last boom and uprooting. A chilling warning for a city that has paid – and still pays – a high price for the pervading presence of organized crime.

Related Posts

The COVID-19 pandemic brought to the fore lasting structural fragilities and inequalities: An analysis of the situation is Southern Italy

“Here we survive, we rig-up, we try to move on, in every way we can. It’s already difficult for us to make it to the end of the day, can you imagine what it’s like after three months with no income?” asks Salvatore, 50, as he takes long puffs from a cigarette, filling the air of his living-room with thick smoke. A father of five, he has worked all possible jobs, all of them in the informal sector, since he left school aged 7. Without a formal contract or social security, his name is nowhere to be found in the employment databases. He has done everything to make ends meet: plumber, carpenter, tailor, electrician, mechanic. Before the lockdown, his daily-wage work as a bricklayer was barely enough to put bread on the table. When the lockdown was imposed following the COVID-19 outbreak, his life-line got interrupted and, with no savings at hand, he experienced the hardest time in his life. “We are used to suffering, but this was worse,” he says with a mix of shame and resignation. For many in Southern Italy, the lockdown turned out to be a crisis within the crisis that mainly affected vulnerable and marginalized groups as well as informal workers.

Streets are usually packed and loud in Naples, where life’s hustle and bustle are the main feature of Southern Italy’s biggest city. Laid at the foot of one of the most dangerous volcanos in the world – the majestic Vesuvius, a sleepy giant and yet a constant threat to the inhabitants – the city leans on a tuff halfmoon that encircles the Gulf of Naples, right at the center of the Mediterranean Sea. A crossroad of cultures, Naples fulfils the stereotypes it is associated with: noisy, frantic, dirty. Its old center is a maze of dark alleys separated by wide avenues paved during the “rehabilitation” – the urban regeneration carried out during the unification of Italy and after the cholera epidemics. It is a restless hive of activities with its busy markets, its smells and sounds. During the lockdown days, however, the stillness and silence that reigned in the streets felt unreal – it was as if someone had pressed the pause button.

Despite a propension towards chaos, a bad reputation as rule-breakers and a lower diffusion of the virus compared to the wealthier Northern Italian regions, people in Naples have been strict in obeying the nation-wide lockdown imposed in mid-March in an attempt to curb the spread of the disease. The usually crowded and teeming streets now emptied of people and life had something sinister. People would lean out of the window in despair, as if they were waiting for something to happen – like prisoners waiting for their release. Policemen were deployed at every corner to check on the compliance with the ever-changing Prime Minister’s decrees that, piece by piece, eroded personal freedoms in the name of public health.

After quarantining two “red zones” in Northern Italy, as coronavirus kept spreading, in early March the government imposed draconian containment measures across the country. In the Northern regions – the epicenter of the contagion accounting for most of the cases – the pandemic overwhelmed what was believed to be one of Italy’s most efficient health care systems, which are funded by the State but administered at the regional level. While the socio-economic divide between North and South is rooted in history and stems from structural and infrastructural differences, the pandemic and the longest lockdown in Europe exacerbated it. The North is the economic engine of the country and, even though COVID-19 decimated an entire generation, for the sake of saving the economy many factories never came to a real halt thus helping the virus spread. In Lombardy, the region where Milan is located, the mortality rate was among the highest in the world. It was feared, however, that in the poorer and lesser industrialized South the virus would wreak havoc to the already fragile healthcare system and that the effects of the economic crisis triggered by the lockdown would be more intense and will have deeper consequences. Here people are used to expedients to survive and, as expected, the repercussions for those who were already at the margins of society have been devastating. The pandemic disrupted their fragile survival mechanisms making social inequalities even starker, thus creating new marginalities.

Hidden in the winding lanes of Montesanto district in Naples, there is a two-story building known as Sgarrupato(“crumbling” in the local dialect) where volunteers from the Spazio DAMM and the activism and resistance movement 7 Novembre provided food to some 350 families who were struggling to make ends meet during the lockdown. Maria, wearing mask and gloves, is packing bottles of tomato sauce and other essentials to be distributed in the adjoining Quartieri Spagnoli. “We are unemployed ourselves, but we try to help those who are in need. As public institutions are absent and the parameters to access food stamps are so strict, many people are cut out,” she says as other volunteers gather outside the building to distribute grocery bags to an ever-growing list of families in need. From a small volunteering activity, this grassroots food distribution grew to become a fully-fledged assistance service that helped contain the emergency as well as the risk of criminal infiltrations in the gaps left by the State. The solidarity net in Naples in fact reached a capillarity and efficiency that went way beyond the institutional one. “Many self-managed mutualism networks have come together in these difficult times. They are partly made up of political activists, but also lots of people from civil society, from the singer to the mechanic, to the taxi driver who is currently not working,” explains Alfonso De Vito, who is part of a local housing rights movement. These grassroots mutualism networks – made of too many organizations to name them all – have helped some 2,000 families get by. “This cross-section of society is the most beautiful part of this terrible story – says De Vito – but this narrative cannot be an alibi for the institutions not taking responsibilities.”

With unemployment rates three times higher in the South than in the North and a strong incidence of irregular work, the cash shortage and the bureaucratic slowness of economic aid packages made the risk of social tensions in Southern Italy a concrete perspective. Early into the lockdown, intelligence agencies warned the authorities of “a potential danger of spontaneous and organized riots and rebellions” in the South: due to cash shortage, many families were struggling to fetch a meal, pay the rent and fulfill the most basic needs. “In Naples and its metropolitan area there are segments of the population who live off daily subsistence. In the lockdown phase, this type of economy disappeared completely: people went from an income of 20 euros per day [22 USD], to null. The people working in this segment are the most vulnerable because they cannot benefit from any social safety-net or public welfare,” explains Prefect of Naples Marco Valentini. With government emergency aid packages reaching late and only a fraction of the needy, it was solidarity and mutualism to help people cope with the most immediate need of the crisis: hunger. The city’s response to the socio-economic emergency was an incredibly efficient network of self-organized collectives that provided families with low or no income with groceries and homeless people with a hot meal. This social lifeline was the product of volunteering and grassroots donations.

Besides secular and Catholic organizations, there was also an effective collaboration with the Buddhist and Senegalese communities. Many private citizens also set up to prepare and distribute food to those who could not abide by the rule of #iorestoacasa (I stay home). At noon in Piazza Mercato, a long, ordered queue slithers from the Mensa dei Poveri (soup kitchen). “We are the angels of the epidemic,” says Father Francesco, while Stefano, a yoga teacher, and other volunteers from Responsabilità Popolare are preparing food in the canteen next to the Basilica del Carmine. When the lockdown was announced, many homeless shelters – including showers and lockers – and soup kitchens were shut down out of sanitary concerns. “Before the pandemic, we used to distribute around 150 meals a day, now we prepare 700,” says the Carmelite Father in a rare pause from the fervid kitchen activity. “Food is not a problem, we can manage, but for many it is impossible to follow the basic hygiene rules: it is a sanitary emergency.” Many have resorted to washing in the subway’s toilets. It is an army of people sharing old and new vulnerabilities: homeless, migrants, clochards, but also people made poor by the pandemic. These days, poverty is spreading at a fast pace in different segments of society.

Among the groups relying on food aid there are also the so-called “new poor.” In a situation where marginalities are overlapping and piling up, the lack of cash put many families at risk of losing the roof over their head. Many tenants never formally signed a lease: a widespread malpractice encouraged by owners themselves in order to avoid taxation. Residents without a regular contract were not able to access rent aid measures and are now in danger of losing their homes. “We are falling into a much poorer economy. The risk is that after the health pandemic, there will be an evictions’ pandemic,” warns De Vito from the housing rights movement. “The economy has come to a halt and so has the income for many people. How will they pay the rent when the aid is over?” More than 64,000 rent aid requests were filed in Campania (the region where Naples is located), while 10,000 are the eviction procedures in place and many more are expected later in the year. Three months of cash flow crunch have taken a heavy toll on the population and on the economy. The fear is that criminal organizations could profit from the economic discomfort many families – and businesses – are presently faced with.

Camorra –the organized crime syndicate from the region of Campania and one of the different mafias that exist in Italy like the ‘Ndrangheta in Calabria, the Sacra Corona Unita in Puglia and Cosa Nostra in Sicily – is a complex organized crime phenomenon whose history goes back to the 19th Century. Until the 1980s, the Camorra was mainly focused on controlling the territory through racketeering, prostitution, weapons and cigarette smuggling. Since then, the Camorra has also acquired a significant presence in other European countries due to its role in international drug trafficking. With the 1980 earthquake in Irpinia, the Camorra began to meddle with public funds for reconstruction: the new business consisted in setting up construction enterprises, and then influencing policies by guaranteeing support and bribes to local politicians in exchange for tenders. From the 1980s onwards, the Camorra went transnational – making use of the deregulation imposed by the globalization – making huge illegal profits that constantly need to be re-invested and laundered. Public administrations are also exposed to criminal infiltrations as the aim of the mafias is to manage and convey public money on activities which are relevant to their scope.

Monitoring the many ways in which organized crime adapts to changing conditions is a real priority in a city like Naples. “Here, the risk of criminal infiltrations is a very sensitive issue due to the significant presence of organized crime. Our first worry is to prevent organized crime from providing criminal welfare,” explains Prefect Marco Valentini. “There are ongoing investigations on the role that the Camorra tried to play during the lockdown phase, particularly in the provision of food aid to families in need,” he asserts. Yet, according to the Prefect, the current post-lockdown phase is the most delicate. In terms of prevention, authorities are implementing a number of measures in view of the economic restart in September, considered a critical date. “Since organized crime has considerable cash, it is possible that through new and old usury mechanisms – not only loans but also donations – criminal organizations may take advantage of the difficult situation that small businesses and companies are facing.”

The lockdown costed the Italian economy 47 billion Euro (52 billion USD) each month, 10 of which in the South. Svimez, a non-profit organization promoting the study of South Italy’s economy, foresees that in 2020 the country will face a Gross Domestic Product (GDP) contraction of 9.3 percent: 9.6 percent in the Centre-North and 8.2 percent in the South. A recent study by the same non-profit shows that the North-South economic divide will further deepen during this year: while the costs of the lockdown and the GPD collapse will be heavier in the Northern regions, the Center-North of the country will lose 600,000 jobs and the South 380,000. Hence, the latter – already in recession before the pandemic – will proportionally suffer the greatest impact of the crisis in terms of occupation and its growth will be halved by next year. In the Southern regions there are also the highest rates of poverty and shadow economy, according to data by the national statistical institute. Families living in relative poverty are estimated at just over three million, with the Southern regions of Calabria, Campania and Sicily registering the highest incidence. Shadow economy and informal work are also more present in the South than in the North: Calabria is the region where the weight of the underground and illegal economy is the greatest, with 20.9 per cent of the total added value, followed by Campania and Sicily. In those segments, money has stopped circulating, hence a part of the population has stopped spending.

In July 2020, two months after the lockdown has been lifted, streets in Naples are again bustling with people: as life seems to flow back city’s veins, the emergency is far from over. Even though streets are busy again, it is clear that business is not fully back yet. Many restaurants and shops have not lifted their shutters and the cash crisis is palpable. “We have a 50 percent drop in the sales of Margherita pizzas,” states Coldiretti, the association of food producers. “We work mainly with takeaway, but tables are empty,” explains Antonio Improta from Pizzera 22 in the Pignasecca district, one of the oldest open-air market of the city of Naples. “The distance between tables imposed by the institutions has more than halved the seats. Due to the economic crisis, many people prefer to do without eating out.” In a city where restaurants were usually always full, and dining out is reasonably cheap, it is unusual to see them so empty. As pizza consumption acts as a market indicator, numerous restaurants, bars, clothing stores and other activities are also gasping for air. The collapse of pizza sale is a significant warning for a city like Naples: the drastic downsizing of its market is the mirror of a “post-war” economy.

The battle against the virus has often been compared to a war, as if the word pandemic were not enough telling of the emergency many countries have experienced. In the current post-lockdown phase, many analysts are setting parallels with the 1945 post-World War II recovery. The frequent reference to post-war times in the media – despite the obvious differences – has a self-delusional function aimed at encouraging the population and boosting national unity. Yet, while in post-war economy the demand could not find a corresponding offer, the opposite is happening today: goods on offer are available, but there is little cash and even less will to spend it. The fear is that, in an era that has witnessed an unprecedented interconnection and globalization, it will take much longer than in post-war times for economies to recover. United Nations Secretary-General Antonio Guterres said that the “economic impact will bring a recession that probably has no parallel in the recent past.” The shock effect of the COVID-19 emergency also revealed all the flaws and injustices of our societies, worldwide.

In Italy, the economic system runs on two-speeds with the country spit in two: North and South of Rome, the national capital. The lockdown plunged Southern Italy’s absolutely precarious economies into a deep crisis. “Given a widespread cash problem,” says Luigi Cuomo, racketeering expert at Libera, an association working against mafias “today there is both a strong demand and an equally strong supply of loans by organized crime. The reopening [of activities after the lockdown] prompted the need for cash, but the Italian banking system is among the most obtuse and medieval banking systems in Europe. The failure in granting legal credit allows illegal, criminal credit to flourish,” he continues. The Mafia – a term originally associated with the Sicilian Mafia, now often used collectively to include all regional criminal outfits – lends money not only to grow its capital but also to infiltrate legal businesses to launder its own capitals. “All usurers are criminals, but Mafia’s usury is growing at a concerning pace in recent years – explains Cuomo – it not only produces income, but it also infiltrates businesses: it launders illicit capital by putting it back into the legal market, it ousts troubled entrepreneurs by first taking control of the company and then of its ownership.”

The Prefecture of Naples is closely observing the phenomenon. “We are constantly monitoring changes in shareholder structure, or company transfers, or branches of it,” says Prefect Valentini. “Stock markets and transfers are a spy: if data is anomalous it leads to suspicion of a criminal intervention aimed at influencing the life of that company.” Even more than any other business, mafias observe the market trends and adapt to the changing context. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the Camorra also reinvented itself in new sectors: the most important is the business of PPE [Personal Protective Equipment], such as the production of gowns and masks, says Valentini. However, usury is the first resort for an activity in crisis. Usury is also an effective money-laundering mechanism: the social emergency caused by the coronavirus has been a great opportunity in this sense. “By lending money, they [the criminal cartels] risk very little and have huge returns. Today they do not even need to coerce people into their illegal money-lending schemes, victims are already flocking towards them. At first sight, the usurer appears as a comforting figure, the one that comes to help you – says Cuomo – a honeymoon that in some cases can last long, in other cases less. Only then, victims will begin to seek help and report.”

It is too early now to assess the impact of usury during the COVID-19 pandemic, according to former racket victim and judicial witness Luigi Ferrucci, President of the Italian Federation of anti-racket and anti-usury associations (FAI), figures will emerge in the long run. In the last two months the Prefecture of Naples has received 26 reports from entrepreneurs who stood up to oppose criminal harassment and have faced increasing difficulties to reintegrate their companies into the healthy productive fabric of the country. “People who fall into money lending schemes take time before they ask for help. We have introduced a new tool, an online listening desk that allows victims to get in touch with us and talk to our experts. We have to be attentive in detecting new dynamics and this can be done only at the grassroots level.” According to Libera’s Cuomo, the State must think of new loan models, not necessarily through the banking system, “whose strict and inaccessible credit regulations make [the banks] victims of their past mistakes,” he explains, “It is necessary to allow private individuals to lend money [in a regulated manner] in competition with banks, so as to trigger a virtuous mechanism and annihilate usury.”

Time is crucial in this context. “The State must act before Mafia does,” urges Rosario Stornaiuolo of the consumers’ association Federconsumatori. “European aid packages must reach small entrepreneurs before the Camorra lends them money first and then usurps their companies, thus also benefitting from public aid.” It is a call for de-bureaucratization in a country where procedures are often lengthy and complex. Camorra is no longer the same as in the 1970s or 1980s, it has evolved both in scope and reach. “Today it is entrepreneurial, it is run by white-collar, educated people who are able to understand these mechanisms.” Food catering and tourism are the main sectors under observation in Naples after the COVID emergency. “Before COVID, these were driving sectors of the city’s economy,” recalls the Prefect Valentini, “Especially in recent years, Naples witnessed an exponential increase in tourism: these sectors are the most exposed now.” The city center, until recently turned into a touristic amusement park, is spectral these days: all activities related to the tourism business are suffering a lack of customers and are at risk of going bust and could hence easily become targets of criminal infiltrations.

Unlike other entrepreneurial actors, Camorra seems to have an infinite availability of cash that needs to be pulled back into the market. Camorra, though, like every other business, has suffered from the current crisis: its supply chain was partially disrupted and experts agree that usury is the only upward activity to produce hegemony in this context. “We believe the lockdown affected also the criminal economy,” says Libera’s Fabio Giuliani. The lower segments of the drug trade – the open-air drug-dealing markets – and their relative profits suddenly dropped. Fabio Giuliani explains that “the drug-dealing outposts where users buys drugs from local criminal cartels have suffered significant losses, to such an extent that the demands for methadone by people who could not fetch their doses during the lockdown has significantly increased.” Despite the losses, the Camorra is the only big player in the market economy that still has cash availability in a time of recession. “In some districts in Naples the criminal cartels have distributed food aid and handed out money, from 50 to 500 Euro,” explains Fabio Giuliani. “A parastatal welfare aimed at building consensus in a specific territory, Camorra knows how to build strong ties and a solid economy.”

In this unfolding crisis, the mafias are trying to increase their hegemony. Prevention seems to be entrusted entirely to civil society associations engaged in providing assistance against usury. These civic networks represent a great moral asset, but they are certainly not enough at an operational level. “Associations and cooperatives against the mafias are experiencing a great crisis,” admits Fabio Giuliani. “It seems that there are always other priorities. Today, the top priority is revitalizing the economy at any cost. During the lockdown, it was the civil society to keep the boat afloat. The focus is now on recovery, while the social network that has proven crucial during the crisis has been placed on the back burner. Today,” warns Giuliani “Camorra has an even greater infiltration capacity compared to the 1980s,” the years of its last boom and uprooting. A chilling warning for a city that has paid – and still pays – a high price for the pervading presence of organized crime.

SUPPORT US

We like bringing the stories that don’t get told to you. For that, we need your support. However small, we would appreciate it.