The Nepali influencers that Abhinav Shahi, an 18-year-old, followed on Instagram, flooded his feed with content urging people to join the “Gen Z” protest against corruption on September 8 in Kathmandu, Nepal’s capital. Shahi, who had graduated from high school only a month ago, felt agitated by the inefficiency of the Nepali government, whether it was the delayed overpass construction in Gwarko or the bureaucratic red tape in obtaining his government-issued identity card. But the government’s latest heavy-handed social media ban sparked the youth’s rage; it felt like a tipping point.

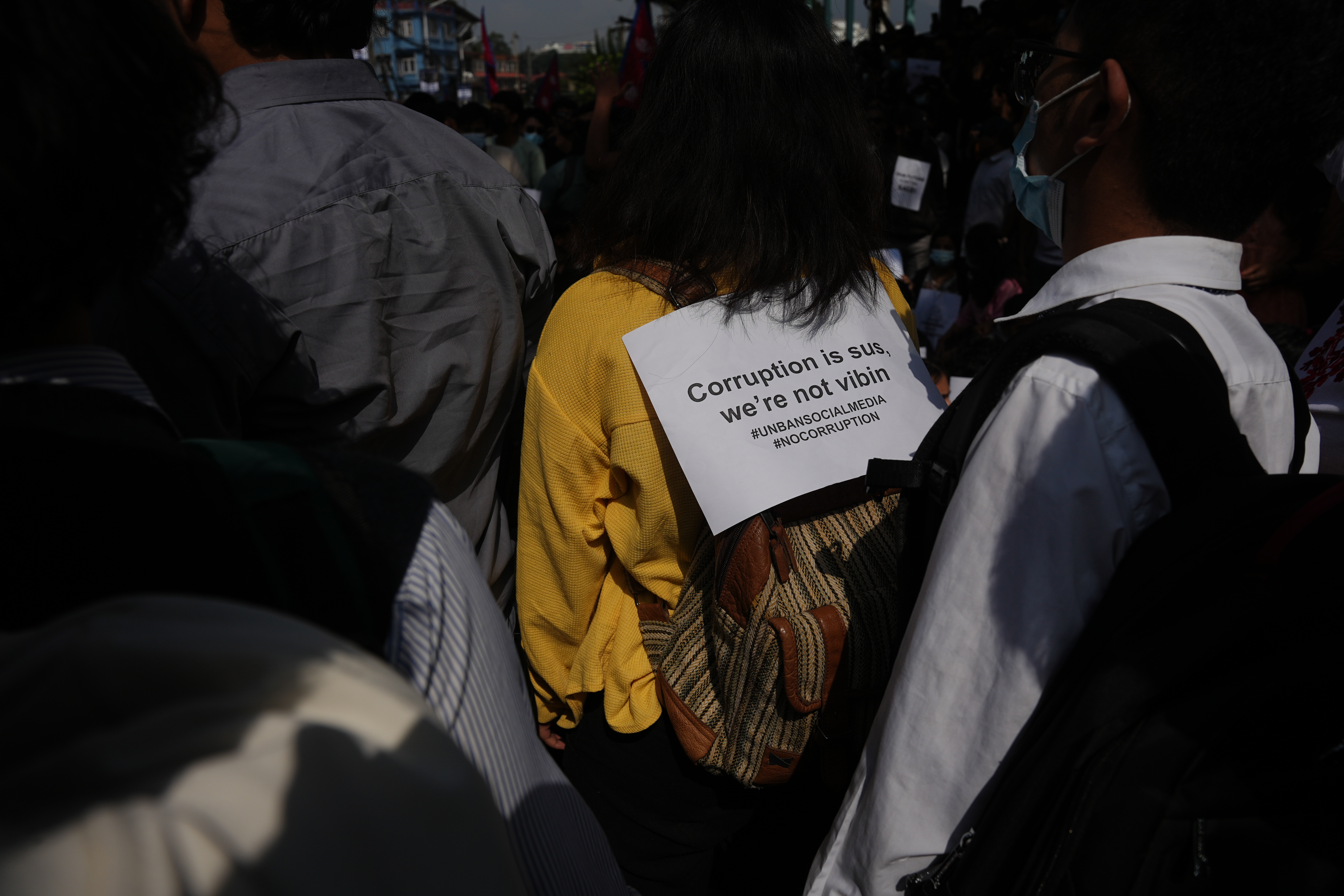

Many others felt the same. Though they used VPNs to bypass the social media ban, the state’s attempt at restricting their freedom of speech had already unleashed pent-up anger towards the establishment.

Gen Z refers to those born between 1997 and 2010. In Nepal, young people have long felt frustration — first by the lack of good governance following the monarchy’s overthrow in 2006, and later by the new constitution adopted in 2015, which failed to bring about meaningful changes.

At around 11 am on September 8, Shahi joined the gathering of thousands at Maitighar Mandala in Kathmandu. It was Shahi’s first time joining a protest. His stomach churned, but the urge to finally speak out was stronger. The protest began peacefully, with attendees making speeches and playing music. Around noon, the air shifted as a few protesters revved their motorcycle engines and fired silencers. A few voices rang out: ‘Let’s march to the parliament building!’ Curious to see what would unfold, Shahi rushed to the front of the crowd, unaware of how quickly the situation would spiral into violence.

Shahi described, as the march pressed on, police fired tear gas shells, which protesters hurled back at them. The clash escalated quickly: the crowd pulled down the parliament fences, entered the premises, and the police charged with wooden batons. On the frontlines were some students in school uniforms, flinging stones and shouting at officers not to strike them. At the main entrance of the Parliament, Shahi recalled, the police were unusually restrained—each time protesters pushed against the barricade, the officers stepped back.

Around two in the afternoon, amid the tear gas, batons, and stones, Shahi ducked for cover as police began firing rubber bullets and then live rounds. He recalled seeing people collapse around him, their bodies bloodied. Even in the face of such horror, Shahi refused to back down. “It was the heat of the moment, an adrenaline rush… I didn’t move until the police shot me with a rubber bullet in my right hand,” Shahi said. “My jacket was drenched in blood. The pain was unbearable.”

Thousands joined the protests in Kathmandu and other cities across Nepal, including Itahari, Pokhara, and Bharatpur. On that day, the Nepali government killed 19 people in the protests. One of them was 23-year-old Rashik Khatiwada; police shot him twice in the chest. His mother, Rachana Khatiwada, 45, while waiting outside the mortuary, said, “I raised my only son with so much love, never once raised my voice at him. How could the state shoot him? Would they ever shoot their own children like this?” She added, “I don’t want any compensation. Can someone bring my son back? I want to hear him say ‘mami’ one more time. I wish I had died instead of him.”

The Gen Z movement, a loosely organized collective, said it had planned the anti-corruption campaign for weeks. But when the government, led by the Communist Party of Nepal (Unified Marxist–Leninist) in coalition with the Nepali Congress, banned 26 social media platforms, including Facebook and X, for failing to register, it drove people to the streets. Underneath that trigger lay deeper grievances shared across generations: mounting anger with repressive tendencies, rising unemployment, and long-unmet democratic aspirations. Nepalis are still coming to terms with the upheaval. While the movement has sparked hopes for change, many worry it could also undo hard-won democratic gains from earlier struggles. Nepal now faces a moment of reckoning: whether this uprising marks the start of a new political order or another cycle of instability.

At the mortuary on September 9, as relatives of the victims waited to see the bodies of their children, protests across Nepal turned deadly. Enraged by the state-led massacre, people stormed the streets. That same day, Prime Minister K.P. Sharma Oli resigned. But the crowd had turned violent, setting fire to the parliament, government buildings, and politicians’ homes.

At least 72 people were killed in the deadly unrest, including 59 protesters, three police officers and 10 prisoners. Some protesters died in clashes with the police, and as riots spread, over 15,000 inmates escaped, with several dying in the ensuing jailbreaks. Protestors themselves were also trapped in buildings ablaze.

For writer and indigenous rights activist Indu Tharu, the destruction carried symbolic weight: “These were symbols of oppression—places where corruption happened, places where they forged suppression plans.” Yet beyond their symbolism, the losses were staggering: damages were estimated at three trillion Nepali rupees, nearly half of Nepal’s GDP.

Built-up Anger

Youth uprisings have long defined Nepal’s political history. In 1951, young members of the Nepali Congress played a pivotal role in leading the democratic movement that overthrew the 104-year-long Rana regime and established a constitutional monarchy. In 1980, student activism forced the monarchy to call a referendum, and a decade later, in 1990, political parties and their youth wings dismantled the Panchayat system. The Maoists’ decade-long People’s War from 1996 to 2006 also relied heavily on young people, including child soldiers, many from marginalized ethnic groups and underprivileged castes. In 2008, student unions were a big part of the movement that led to the abolition of the 240-year-old Shah monarchy.

In recent history, since 2015, Nepal has experienced political instability, with eight different governments in just a decade. K.P. Sharma Oli of the UML, Pushpa Kamal Dahal ‘Prachanda’ of the Communist Party of Nepal (Maoist Center), and Sher Bahadur Deuba of the Nepali Congress took turns to lead the government. Even as they struck coalition deals with one another, they centralized power within their parties, tightening their grip on the country.

“For decades, these corrupt leaders played a never-ending game of musical chairs. We’d try to remove one, only to find the others were just as corrupt,’ said Bhushita Vasistha, 35, a writer based in Kathmandu city.

“I am hopeful because Gen Z had the guts to move beyond incremental reforms and claim a revolution. They’ve thrown the players out and dismantled the game,” Vasistha added.

In addition to monopolizing power, the political leadership’s failure to deliver on promises of equality deepened disillusionment for many. JB Biswokarma, a social justice researcher, commented, “People have been frustrated by the government’s blatant irresponsibility towards the public. Since the start of the peace process, leaders had made a political agreement to end all forms of discrimination against historically marginalized groups. And to stop economic exploitation.”

Ending discrimination should have been their first priority. “Instead, Article 47 of the constitution stated that the state shall make legal provisions to implement fundamental rights within three years of the constitution’s commencement,” Biswokarma added.

Today, a decade later, the state has still not fulfilled its commitment to the people of Nepal.

Socio-economic-political issues boil over

For many Nepalis, living away from families to make ends meet has long been the way of life. Unemployment during Nepal’s armed conflict from 1996 to 2006 continued even after the peace process, and this encouraged many Nepalis to migrate abroad for work.

“I have always been concerned about how many in this generation have grown up without their parents,” said art educator Ujjwala Maharjan, 36, adding, “the government seems to have kept them in a pipeline to go abroad.” Remittances are more than a quarter of Nepal’s GDP. The dollars sent home by over two million Nepalis living abroad help cover the country’s massive trade deficit, a lifeline for the economy, which is hobbled by a stagnant manufacturing sector.

People with higher incomes, better education, and stronger family ties have migrated to developed countries such as the United Kingdom, the United States, Australia, European countries, Japan, and South Korea. Student migration has become a major pathway for migration. Between 2014 to 2023, the number of Nepali students heading to developed countries quadrupled. However, people from the poorest regions of Nepal migrated to India for work, further widening the socio-economic inequality of Nepalis.

Like many youths of Nepal, at least seven of the youths killed on 8 September–Ayush Thapa, 19, Nikita Gautam, 19, Shree Krishna Shrestha, 22, Rashik Khatiwada, 23, Abhishek Shrestha, 23, Ishwot Adhikari, 26, Gaurav Joshi, 27–were preparing to leave for countries such as France, Denmark, Australia, Malta, the UK, and Qatar.

Amid a sluggish economy and lack of employment, a string of corruption scandals in Nepal underscored a deep collusion between political leaders, bureaucrats, and business elites. Last year, Transparency International, a global coalition against corruption, ranked Nepal as one of the most corrupt countries.

In an infamous corruption scandal in 2023, more than 30 people, including former ministers and senior bureaucrats, were charged with collecting millions from Nepali citizens and falsely promising them resettlement in the US under Bhutanese refugee status.

In the “Lalita Niwas land grab” case in 2024, more than 100 individuals, including former government secretaries, were convicted of illegally transferring over 14 acres of government land near the Prime Minister’s residence to private individuals. The court, however, acquitted the political leaders who had been involved in making those decisions.

There was yet another “visit visas” scandal earlier this year. The former Chief Immigration officer at Nepal’s Tribhuvan International Airport, and other senior officials, were charged with extorting money to illegally issue visit visas to individuals who did not meet the criteria for foreign travel.

The Pokhara International Airport, built with a $216 million loan from China, is also embroiled in corruption. A 2025 parliamentary probe found irregularities worth $105 million, ranging from fake payments to illegal tax exemptions. Since the airport came into operation more than two years ago, it has had only one regular international flight a week.

Despite public outcry against corruption and media exposés, political leaders went scot-free. “The impression people got was that we [parties] don’t need to listen to you. We are the superpower, we built this system, and it will run the way we decide,” said Biswokarma.

State Repression of Freedom of Expression

Leading up to the latest protests, the Nepali government was also becoming increasingly repressive. Using the Electronic Transactions Act of 2006, which prohibits the publication of materials deemed illegal or harmful to social harmony, it curbed freedom of speech.

Earlier in June 2025, the Kathmandu District Court ordered news portals Nepal Khabar and Bizmandu to remove articles about alleged bribery by government officials and even issued an arrest warrant against a senior journalist, Dil Bhusan Pathak. He had accused the son of Nepali Congress President Deuba and former Foreign Minister Arzu Rana Deuba of allegedly misusing their political influence to secure a stake in a five-star Hilton Hotel in Kathmandu.

In 2024, police arrested two youths for posting a Facebook status critical of political leaders and detained another for sharing a video of a crowd shouting slogans against political leaders. These are only a few examples of cases that show an erosion of the constitutional right to freedom of expression.

“We have seen that journalists, activists, and ordinary people asking legitimate questions or speaking up about corruption were targeted under this act,” said Santosh Sigdel, Executive Director of Digital Rights Nepal.

“The act’s vague, catch-all terms like ‘social harmony’, made it open to interpretation. And the authorities misused the act to regulate everything that is published online,” Sigdel added.

In 2024, the government also banned the TikTok app for nine months, citing disruption of “social harmony and goodwill”. And more recently, in February 2025, the government introduced the Social Media Bill, which further threatened the fundamental right to freedom of expression. However, the bill was quashed following the Gen Z protest that led to the dissolution of the parliament on September 12.

Inclusivity in the Gen Z Protests

The state’s style of communication is top-down and one-way; it does not adequately take into account public views while making decisions. “It communicates in a very linear manner; if they have to make an announcement, they put up a notice. But the Gen Z is a global generation that questions, interacts, and engages in dialogues,” said Prakash Chandra Jimba, 28, a documentary filmmaker.

The Gen Z youth started the anti-corruption protests digitally on Reddit, TikTok, Discord, and Instagram. Jimba, a protest participant, explained that the wide communication gap, a three-generation divide between Gen Z and those in power, meant it dismissed the uproar as tantrums of a generation that “Plays PUBG, is uninterested in politics, and is concerned only about social media.

Inclusion has been a key aspect in this movement, and different groups of Gen Z have questioned the socio-economic position of those whose voices are heard the loudest. As Nepal faced turmoil after the state’s massacre on September 8, Nepali youths logged into the Discord app to discuss, strategize, and even vote for a new prime minister to lead the interim government. In a Discord poll, 50% voted for Sushila Karki, the former Chief Justice of Nepal, who served for nearly a year in 2016 and remains the only woman to hold the position.

A Gen Z team member from Dhangadi, a city in far-western Nepal near the Indian border, Sarita Joshi, also voted for Karki on Discord. “We tried to share the link widely, encouraging everyone in our community to vote,” 24-year-old Joshi said. Since then, she has been trying to connect with the Kathmandu Gen Z team to discuss forming a stable interim government, but given the instability, they have not been able to coordinate yet.

This process of electing an alternative leader as the head of the government also resonated with Nepalis living abroad. Aadarsha Bhandari, 19, studying in Texas, US, said, “I made videos explaining the Gen Z agenda of how my grandfather fought against the Rana autocracy, my father fought against the Panchayat system, and my brother fought to abolish monarchy, but the elites still rule us.” He also cast his vote for Karki and felt a sense of connection to his country’s unfolding political changes.

But for others, participation was less direct. Damber Khadka, 24, who is currently working in Dubai, didn’t have the Discord app. “I couldn’t vote, but my friends shared the [Discord] conversation on TikTok. I put my headphones on and listened to it throughout the day,” he said, sounding optimistic. Two years ago, Khadka had paid a smuggler $2,000 to take him to Europe, but they left him stranded in Dubai. Unable to return home without money, he scrambled to find a job and has been painting cars since then to earn $525 a month, four times Nepal’s per capita income.

Nepal’s Political Future

Reflecting on how most of the Gen Z of his village are in Malaysia, UAE, Qatar, and Saudi Arabia, political commentator CK Lal said, “This is a very urban movement of entitled kids who feel they aren’t getting their due. At that age, the way they think is very filmy. They’ve identified a villain figure, some henchmen; and you become the savior, a new hero, and tread the same path.”

“With Sushila Karki as the prime minister, what will change? It will only be regressive changes,” Lal added, concerned about a possible rollback of federalism and inclusion and a rise in nepotism in terms of, “You were with us, and you were not” during the movement.

Indeed, the names emerging in Karki’s interim government suggest it is far from inclusive. As of September 15, she had appointed three ministers: Rameshore Khanal as finance minister, Kulman Ghising to oversee the ministries of a) energy, water resources, and irrigation, b) physical infrastructure and transport, and c) urban development. Om Prakash Aryal became the home minister and minister of law.

Expanding her cabinet, on September 22, Karki appointed four additional ministers for commerce, agriculture, and education and tech sectors.

The majority of the people in the interim cabinet are from privileged caste groups that have long been overrepresented in Nepali politics. Except for the prime minister herself, all other ministers are men.

Karki also appointed a new attorney general, Sabita Bhandari. While the mainstream media celebrated the appointment of Nepal’s first woman attorney general, there were concerns about her decision to defend Sandeep Lamichhane, the Nepal cricket team captain, in a rape case in 2024. Lamichhane was initially convicted of raping an 18-year-old girl. The decision was later overturned, but the survivor, worn down by court battles and public vilification, left Nepal seeking safer pastures.

Similarly, another famous minister in the cabinet, long hailed for substantially decreasing power cuts in Nepal, was questioned for his role in plans to build a high-voltage electricity transmission line through the settlement of an Indigenous community, affecting over 500 households.

Following current politics, Chandan Kumar Mandal, 34, a communications professional and a journalist, said, “We are very concerned. What if everything is uprooted? Will whatever the Madhesh Andolan achieved–federalism, representation– be thrown away?”

During the drafting of the current constitution, the activists of the Madhesh Andolan had raised concerns about federalism, proportional representation, and equal citizenship. They faced brutal state crackdowns during 2007, 2008, and most intensely during the constitution’s promulgation in 2015, resulting in over 45 deaths that year alone.

“Even if we may not be united on every issue, anything less than a secular, federal democratic republic of Nepal is non-negotiable.”

Despite the presence of diverse groups in the Gen Z protests, young men have dominated, representing the movement at press conferences, official meetings, and social media.“But we know the invisible work happens in the hands of women and queer folks and minorities whose lives are resistance,” said Ujjwala Maharjan, an art educator.

“You need the kind of leadership that can listen and lead with utmost humility. That kind of masculinity we saw on the frontline of the protests and in the leaders they’re trying to choose is worrisome. That is something that needs to be checked. Not just by the people on the outside, but also by those who take it on themselves. It’s necessary to self-reflect.”

Since the protests, some of the Gen Z movement’s demands, such as forming an interim government led by a representative of their choice and dissolving the parliament, have been addressed. Others remain unfulfilled, including holding elections within six months, taking immediate action against those responsible for the violent crackdown on September 8, investigating corruption cases, and amending the constitution.

“Looking back at the destruction, I feel broken and worried if the country has been dragged 20 years back. I am determined to make this right and build a Nepal I won’t have to leave,” said Abhinav Shahi.

“I hope that was the last protest I will ever attend.”

Related Posts

Inside Nepal’s Gen Z Protests: A Fight Against Deep Political Rot, a Leap to Reclaim Democracy

The Nepali influencers that Abhinav Shahi, an 18-year-old, followed on Instagram, flooded his feed with content urging people to join the “Gen Z” protest against corruption on September 8 in Kathmandu, Nepal’s capital. Shahi, who had graduated from high school only a month ago, felt agitated by the inefficiency of the Nepali government, whether it was the delayed overpass construction in Gwarko or the bureaucratic red tape in obtaining his government-issued identity card. But the government’s latest heavy-handed social media ban sparked the youth’s rage; it felt like a tipping point.

Many others felt the same. Though they used VPNs to bypass the social media ban, the state’s attempt at restricting their freedom of speech had already unleashed pent-up anger towards the establishment.

Gen Z refers to those born between 1997 and 2010. In Nepal, young people have long felt frustration — first by the lack of good governance following the monarchy’s overthrow in 2006, and later by the new constitution adopted in 2015, which failed to bring about meaningful changes.

At around 11 am on September 8, Shahi joined the gathering of thousands at Maitighar Mandala in Kathmandu. It was Shahi’s first time joining a protest. His stomach churned, but the urge to finally speak out was stronger. The protest began peacefully, with attendees making speeches and playing music. Around noon, the air shifted as a few protesters revved their motorcycle engines and fired silencers. A few voices rang out: ‘Let’s march to the parliament building!’ Curious to see what would unfold, Shahi rushed to the front of the crowd, unaware of how quickly the situation would spiral into violence.

Shahi described, as the march pressed on, police fired tear gas shells, which protesters hurled back at them. The clash escalated quickly: the crowd pulled down the parliament fences, entered the premises, and the police charged with wooden batons. On the frontlines were some students in school uniforms, flinging stones and shouting at officers not to strike them. At the main entrance of the Parliament, Shahi recalled, the police were unusually restrained—each time protesters pushed against the barricade, the officers stepped back.

Around two in the afternoon, amid the tear gas, batons, and stones, Shahi ducked for cover as police began firing rubber bullets and then live rounds. He recalled seeing people collapse around him, their bodies bloodied. Even in the face of such horror, Shahi refused to back down. “It was the heat of the moment, an adrenaline rush… I didn’t move until the police shot me with a rubber bullet in my right hand,” Shahi said. “My jacket was drenched in blood. The pain was unbearable.”

Thousands joined the protests in Kathmandu and other cities across Nepal, including Itahari, Pokhara, and Bharatpur. On that day, the Nepali government killed 19 people in the protests. One of them was 23-year-old Rashik Khatiwada; police shot him twice in the chest. His mother, Rachana Khatiwada, 45, while waiting outside the mortuary, said, “I raised my only son with so much love, never once raised my voice at him. How could the state shoot him? Would they ever shoot their own children like this?” She added, “I don’t want any compensation. Can someone bring my son back? I want to hear him say ‘mami’ one more time. I wish I had died instead of him.”

The Gen Z movement, a loosely organized collective, said it had planned the anti-corruption campaign for weeks. But when the government, led by the Communist Party of Nepal (Unified Marxist–Leninist) in coalition with the Nepali Congress, banned 26 social media platforms, including Facebook and X, for failing to register, it drove people to the streets. Underneath that trigger lay deeper grievances shared across generations: mounting anger with repressive tendencies, rising unemployment, and long-unmet democratic aspirations. Nepalis are still coming to terms with the upheaval. While the movement has sparked hopes for change, many worry it could also undo hard-won democratic gains from earlier struggles. Nepal now faces a moment of reckoning: whether this uprising marks the start of a new political order or another cycle of instability.

At the mortuary on September 9, as relatives of the victims waited to see the bodies of their children, protests across Nepal turned deadly. Enraged by the state-led massacre, people stormed the streets. That same day, Prime Minister K.P. Sharma Oli resigned. But the crowd had turned violent, setting fire to the parliament, government buildings, and politicians’ homes.

At least 72 people were killed in the deadly unrest, including 59 protesters, three police officers and 10 prisoners. Some protesters died in clashes with the police, and as riots spread, over 15,000 inmates escaped, with several dying in the ensuing jailbreaks. Protestors themselves were also trapped in buildings ablaze.

For writer and indigenous rights activist Indu Tharu, the destruction carried symbolic weight: “These were symbols of oppression—places where corruption happened, places where they forged suppression plans.” Yet beyond their symbolism, the losses were staggering: damages were estimated at three trillion Nepali rupees, nearly half of Nepal’s GDP.

Built-up Anger

Youth uprisings have long defined Nepal’s political history. In 1951, young members of the Nepali Congress played a pivotal role in leading the democratic movement that overthrew the 104-year-long Rana regime and established a constitutional monarchy. In 1980, student activism forced the monarchy to call a referendum, and a decade later, in 1990, political parties and their youth wings dismantled the Panchayat system. The Maoists’ decade-long People’s War from 1996 to 2006 also relied heavily on young people, including child soldiers, many from marginalized ethnic groups and underprivileged castes. In 2008, student unions were a big part of the movement that led to the abolition of the 240-year-old Shah monarchy.

In recent history, since 2015, Nepal has experienced political instability, with eight different governments in just a decade. K.P. Sharma Oli of the UML, Pushpa Kamal Dahal ‘Prachanda’ of the Communist Party of Nepal (Maoist Center), and Sher Bahadur Deuba of the Nepali Congress took turns to lead the government. Even as they struck coalition deals with one another, they centralized power within their parties, tightening their grip on the country.

“For decades, these corrupt leaders played a never-ending game of musical chairs. We’d try to remove one, only to find the others were just as corrupt,’ said Bhushita Vasistha, 35, a writer based in Kathmandu city.

“I am hopeful because Gen Z had the guts to move beyond incremental reforms and claim a revolution. They’ve thrown the players out and dismantled the game,” Vasistha added.

In addition to monopolizing power, the political leadership’s failure to deliver on promises of equality deepened disillusionment for many. JB Biswokarma, a social justice researcher, commented, “People have been frustrated by the government’s blatant irresponsibility towards the public. Since the start of the peace process, leaders had made a political agreement to end all forms of discrimination against historically marginalized groups. And to stop economic exploitation.”

Ending discrimination should have been their first priority. “Instead, Article 47 of the constitution stated that the state shall make legal provisions to implement fundamental rights within three years of the constitution’s commencement,” Biswokarma added.

Today, a decade later, the state has still not fulfilled its commitment to the people of Nepal.

Socio-economic-political issues boil over

For many Nepalis, living away from families to make ends meet has long been the way of life. Unemployment during Nepal’s armed conflict from 1996 to 2006 continued even after the peace process, and this encouraged many Nepalis to migrate abroad for work.

“I have always been concerned about how many in this generation have grown up without their parents,” said art educator Ujjwala Maharjan, 36, adding, “the government seems to have kept them in a pipeline to go abroad.” Remittances are more than a quarter of Nepal’s GDP. The dollars sent home by over two million Nepalis living abroad help cover the country’s massive trade deficit, a lifeline for the economy, which is hobbled by a stagnant manufacturing sector.

People with higher incomes, better education, and stronger family ties have migrated to developed countries such as the United Kingdom, the United States, Australia, European countries, Japan, and South Korea. Student migration has become a major pathway for migration. Between 2014 to 2023, the number of Nepali students heading to developed countries quadrupled. However, people from the poorest regions of Nepal migrated to India for work, further widening the socio-economic inequality of Nepalis.

Like many youths of Nepal, at least seven of the youths killed on 8 September–Ayush Thapa, 19, Nikita Gautam, 19, Shree Krishna Shrestha, 22, Rashik Khatiwada, 23, Abhishek Shrestha, 23, Ishwot Adhikari, 26, Gaurav Joshi, 27–were preparing to leave for countries such as France, Denmark, Australia, Malta, the UK, and Qatar.

Amid a sluggish economy and lack of employment, a string of corruption scandals in Nepal underscored a deep collusion between political leaders, bureaucrats, and business elites. Last year, Transparency International, a global coalition against corruption, ranked Nepal as one of the most corrupt countries.

In an infamous corruption scandal in 2023, more than 30 people, including former ministers and senior bureaucrats, were charged with collecting millions from Nepali citizens and falsely promising them resettlement in the US under Bhutanese refugee status.

In the “Lalita Niwas land grab” case in 2024, more than 100 individuals, including former government secretaries, were convicted of illegally transferring over 14 acres of government land near the Prime Minister’s residence to private individuals. The court, however, acquitted the political leaders who had been involved in making those decisions.

There was yet another “visit visas” scandal earlier this year. The former Chief Immigration officer at Nepal’s Tribhuvan International Airport, and other senior officials, were charged with extorting money to illegally issue visit visas to individuals who did not meet the criteria for foreign travel.

The Pokhara International Airport, built with a $216 million loan from China, is also embroiled in corruption. A 2025 parliamentary probe found irregularities worth $105 million, ranging from fake payments to illegal tax exemptions. Since the airport came into operation more than two years ago, it has had only one regular international flight a week.

Despite public outcry against corruption and media exposés, political leaders went scot-free. “The impression people got was that we [parties] don’t need to listen to you. We are the superpower, we built this system, and it will run the way we decide,” said Biswokarma.

State Repression of Freedom of Expression

Leading up to the latest protests, the Nepali government was also becoming increasingly repressive. Using the Electronic Transactions Act of 2006, which prohibits the publication of materials deemed illegal or harmful to social harmony, it curbed freedom of speech.

Earlier in June 2025, the Kathmandu District Court ordered news portals Nepal Khabar and Bizmandu to remove articles about alleged bribery by government officials and even issued an arrest warrant against a senior journalist, Dil Bhusan Pathak. He had accused the son of Nepali Congress President Deuba and former Foreign Minister Arzu Rana Deuba of allegedly misusing their political influence to secure a stake in a five-star Hilton Hotel in Kathmandu.

In 2024, police arrested two youths for posting a Facebook status critical of political leaders and detained another for sharing a video of a crowd shouting slogans against political leaders. These are only a few examples of cases that show an erosion of the constitutional right to freedom of expression.

“We have seen that journalists, activists, and ordinary people asking legitimate questions or speaking up about corruption were targeted under this act,” said Santosh Sigdel, Executive Director of Digital Rights Nepal.

“The act’s vague, catch-all terms like ‘social harmony’, made it open to interpretation. And the authorities misused the act to regulate everything that is published online,” Sigdel added.

In 2024, the government also banned the TikTok app for nine months, citing disruption of “social harmony and goodwill”. And more recently, in February 2025, the government introduced the Social Media Bill, which further threatened the fundamental right to freedom of expression. However, the bill was quashed following the Gen Z protest that led to the dissolution of the parliament on September 12.

Inclusivity in the Gen Z Protests

The state’s style of communication is top-down and one-way; it does not adequately take into account public views while making decisions. “It communicates in a very linear manner; if they have to make an announcement, they put up a notice. But the Gen Z is a global generation that questions, interacts, and engages in dialogues,” said Prakash Chandra Jimba, 28, a documentary filmmaker.

The Gen Z youth started the anti-corruption protests digitally on Reddit, TikTok, Discord, and Instagram. Jimba, a protest participant, explained that the wide communication gap, a three-generation divide between Gen Z and those in power, meant it dismissed the uproar as tantrums of a generation that “Plays PUBG, is uninterested in politics, and is concerned only about social media.

Inclusion has been a key aspect in this movement, and different groups of Gen Z have questioned the socio-economic position of those whose voices are heard the loudest. As Nepal faced turmoil after the state’s massacre on September 8, Nepali youths logged into the Discord app to discuss, strategize, and even vote for a new prime minister to lead the interim government. In a Discord poll, 50% voted for Sushila Karki, the former Chief Justice of Nepal, who served for nearly a year in 2016 and remains the only woman to hold the position.

A Gen Z team member from Dhangadi, a city in far-western Nepal near the Indian border, Sarita Joshi, also voted for Karki on Discord. “We tried to share the link widely, encouraging everyone in our community to vote,” 24-year-old Joshi said. Since then, she has been trying to connect with the Kathmandu Gen Z team to discuss forming a stable interim government, but given the instability, they have not been able to coordinate yet.

This process of electing an alternative leader as the head of the government also resonated with Nepalis living abroad. Aadarsha Bhandari, 19, studying in Texas, US, said, “I made videos explaining the Gen Z agenda of how my grandfather fought against the Rana autocracy, my father fought against the Panchayat system, and my brother fought to abolish monarchy, but the elites still rule us.” He also cast his vote for Karki and felt a sense of connection to his country’s unfolding political changes.

But for others, participation was less direct. Damber Khadka, 24, who is currently working in Dubai, didn’t have the Discord app. “I couldn’t vote, but my friends shared the [Discord] conversation on TikTok. I put my headphones on and listened to it throughout the day,” he said, sounding optimistic. Two years ago, Khadka had paid a smuggler $2,000 to take him to Europe, but they left him stranded in Dubai. Unable to return home without money, he scrambled to find a job and has been painting cars since then to earn $525 a month, four times Nepal’s per capita income.

Nepal’s Political Future

Reflecting on how most of the Gen Z of his village are in Malaysia, UAE, Qatar, and Saudi Arabia, political commentator CK Lal said, “This is a very urban movement of entitled kids who feel they aren’t getting their due. At that age, the way they think is very filmy. They’ve identified a villain figure, some henchmen; and you become the savior, a new hero, and tread the same path.”

“With Sushila Karki as the prime minister, what will change? It will only be regressive changes,” Lal added, concerned about a possible rollback of federalism and inclusion and a rise in nepotism in terms of, “You were with us, and you were not” during the movement.

Indeed, the names emerging in Karki’s interim government suggest it is far from inclusive. As of September 15, she had appointed three ministers: Rameshore Khanal as finance minister, Kulman Ghising to oversee the ministries of a) energy, water resources, and irrigation, b) physical infrastructure and transport, and c) urban development. Om Prakash Aryal became the home minister and minister of law.

Expanding her cabinet, on September 22, Karki appointed four additional ministers for commerce, agriculture, and education and tech sectors.

The majority of the people in the interim cabinet are from privileged caste groups that have long been overrepresented in Nepali politics. Except for the prime minister herself, all other ministers are men.

Karki also appointed a new attorney general, Sabita Bhandari. While the mainstream media celebrated the appointment of Nepal’s first woman attorney general, there were concerns about her decision to defend Sandeep Lamichhane, the Nepal cricket team captain, in a rape case in 2024. Lamichhane was initially convicted of raping an 18-year-old girl. The decision was later overturned, but the survivor, worn down by court battles and public vilification, left Nepal seeking safer pastures.

Similarly, another famous minister in the cabinet, long hailed for substantially decreasing power cuts in Nepal, was questioned for his role in plans to build a high-voltage electricity transmission line through the settlement of an Indigenous community, affecting over 500 households.

Following current politics, Chandan Kumar Mandal, 34, a communications professional and a journalist, said, “We are very concerned. What if everything is uprooted? Will whatever the Madhesh Andolan achieved–federalism, representation– be thrown away?”

During the drafting of the current constitution, the activists of the Madhesh Andolan had raised concerns about federalism, proportional representation, and equal citizenship. They faced brutal state crackdowns during 2007, 2008, and most intensely during the constitution’s promulgation in 2015, resulting in over 45 deaths that year alone.

“Even if we may not be united on every issue, anything less than a secular, federal democratic republic of Nepal is non-negotiable.”

Despite the presence of diverse groups in the Gen Z protests, young men have dominated, representing the movement at press conferences, official meetings, and social media.“But we know the invisible work happens in the hands of women and queer folks and minorities whose lives are resistance,” said Ujjwala Maharjan, an art educator.

“You need the kind of leadership that can listen and lead with utmost humility. That kind of masculinity we saw on the frontline of the protests and in the leaders they’re trying to choose is worrisome. That is something that needs to be checked. Not just by the people on the outside, but also by those who take it on themselves. It’s necessary to self-reflect.”

Since the protests, some of the Gen Z movement’s demands, such as forming an interim government led by a representative of their choice and dissolving the parliament, have been addressed. Others remain unfulfilled, including holding elections within six months, taking immediate action against those responsible for the violent crackdown on September 8, investigating corruption cases, and amending the constitution.

“Looking back at the destruction, I feel broken and worried if the country has been dragged 20 years back. I am determined to make this right and build a Nepal I won’t have to leave,” said Abhinav Shahi.

“I hope that was the last protest I will ever attend.”

SUPPORT US

We like bringing the stories that don’t get told to you. For that, we need your support. However small, we would appreciate it.