Algorithmic Politics: How Meta Silenced Palestinian Voices Amid Genocide

The authors of this essay are researchers at 7amleh – The Arab Center for Social Media Advancement, a Palestinian digital rights organization. 7amleh has published extensive reports on Meta’s systematic censorship of Palestinian content, especially during critical periods of conflict and uprising.

The censorship of Palestinian voices is not new, and recent events have thrust this longstanding crisis into global view. As the Gaza genocide unfolded, Palestinians and their allies worldwide found their social media posts about it blocked or shadow-banned. Media outlets, academics, and human rights groups have reported this practice of online suppression for years. Then, the surge in censorship since October 2023 marked an intensification of a troubling pattern, whose roots run deeper.

Ten years ago, a little-known lawsuit against Facebook played a crucial role in setting the foundation for modern power dynamics. It shaped whose voice and perspective can be freely shared on social media, versus which would be suppressed.

In 2015, more than 20,000 Israelis filed a lawsuit against Facebook in the United States, suing the company for $1 Billion due to alleged facilitation and encouragement of Palestinian-led violence against Israeli Jewish citizens. The suit was later dropped, while Facebook publicly announced it would actively partner with the Israeli state to monitor posts by Palestinians. This set the stage for the current digital reality: one where Palestinians are deplatformed for simply posting documentation of human rights violations, while Israeli officials can post openly genocidal rhetoric without consequence.

This dynamic is not unique to the Palestinian context. Amnesty International research detailed how Facebook’s algorithm exacerbated the spread of harmful anti-Rohingya content during the Rohingya genocide in Myanmar in 2017. More recently, in a similar fashion, Meta’s platforms contributed to mass violations of human rights in the Tigray region of Ethiopia. In each context, from Myanmar to Ethiopia, as well as in occupied Palestine, human rights experts have clearly shown Meta’s continual wrongdoing. But not much has changed in its continued practice, showing a lack of intention to change past behavior.

However, May 2021 marked an important turning point when Meta’s biased policies on Palestinians were on display globally. Due to Israeli forces cracking down on Palestinians at Al-Aqsa Mosque and injuring hundreds, and the forced evictions of Palestinian families in the East Jerusalem neighborhood of Sheikh Jarrah, tensions flared and led to the May Uprisings of 2021. During this time, many Palestinians turned to Meta’s social media platforms to post documentation of Israeli human rights violations, particularly surrounding the forced evictions in Sheikh Jarrah, and were met with mass suppression and censorship.

Widespread acknowledgement of the problem led Meta’s Oversight Board to recommend that an independent third party issue a Human Rights Due Diligence report. Over a year later, when the report was finally released, it echoed many of the same points civil societies had been raising for years. It showed that Meta’s content moderation practices and policies were biased against Palestinian and Arabic content, leading to overmoderation and a negative impact on human rights, while likely undermoderating Israeli Hebrew language content. The report also provided 21 recommendations for Meta, of which the company agreed to implement 20, in part or in full. However, one year after the report was released, Meta issued its first progress report, which showed little evidence of progress made on any of the actions. That progress report was released in September of 2023, just weeks before October 7, when Hamas and other Palestinian militant groups carried out incursions in Southern Israel.

Meta’s Biased Algorithm and Content Moderation

In October 2023, with a massive influx of content being posted about Israel and Palestine, especially related to what was happening in Gaza, Meta was caught entirely unprepared (albeit after years of civil society raising the alarm, as well as a two year Human Rights Due Diligence process, all of which leaves one to wonder how much of this incompetence was by design). As a result, Meta took drastic measures and lowered their automated content moderation confidence interval for Arabic language content in Palestine to 40%, and then eventually to as low as 25%. What that means is Meta’s automated systems, which flag and take down content it believes to be violating the platform’s policies, only needed to be 25% confident that a piece of content was violative to take it down, and all without any human moderator acting in the process. This led to massive censorship and suppression of the Palestinians’ freedom of expression, and also directly impacted what people around the world were able to see coming out of Palestine online. Meanwhile, Israeli government, military officials, and community leaders were able to freely post genocidal and racist rhetoric, advocating for the collective punishment of all Palestinians. The juxtaposition was jarring, and once again, many around the world took notice.

In December 2023, Rabbi Moshe Ratt, influential among Israeli settlers in the West Bank, composed a long post on Facebook, which was accessed by The Polis Project. An article in The Conversation noted this post for its advocacy of genocide. Ratt had claimed that some people might have struggled in the past with the question of destroying an entire people, including women and children, but they didn’t face this dilemma anymore. In a reference to Palestinians as “Amalek” (the enemy of Israelites as per the Hebrew Bible), he added, “There are peoples who have reached such a depth of evil and corruption that there is no other way but to wipe them out of the world without a trace [translated by Google].”

In another instance in September 2023, Al Jazeera Arabic presenter Tamer Almisshal’s Facebook profile was deleted by Meta a day after the airing of his programme that investigated Meta’s censorship of Palestinian content.

At the end of 2024, 7amleh (The Arab Center for the Advancement of Social Media), with which the writers of this piece are associated, published a report on Meta’s censorship by documenting testimonies of 20 Palestinian influencers, journalists, and media outlets. Users described deleted posts, suspended accounts, and restricted reach, resulting in economic losses, professional damage, trauma, and violations of digital rights.

Adnan Barq, a Jerusalem-based journalist with 285,000 Instagram (now owned by Meta) followers, was mentioned in the report. He said Meta restricted his ability to share Palestinian stories from Gaza. On October 7, 2023, he was banned from Instagram Live despite posting nothing about the events. When Barq later used Instagram’s collaboration feature to amplify Gazans’ voices, he was blocked after two posts. A Meta employee later admitted the restrictions were “a mistake,” Barq said, but other restrictions persisted. His story views plummeted from 20,000-30,000 before the war to just 3,000-7,000 after. “I started receiving many messages from friends and acquaintances asking why I stopped posting on Instagram,” Barq recalled. “I was surprised by that because I was posting all the time, but it turned out that my content was not reaching them.” The shadow-banning cost him brand collaborations and income.

This brief telling of how Meta has evolved to moderate speech about Israel and Palestine over the years points to larger dynamics across online platforms, which allow for an intentional manipulation of global understandings around what is happening in the region. The state of Israel has a vested interest in this, as illustrated by its tens of thousands of voluntary takedown requests to Meta each year. Meta, even without having any legal obligations, abides by these requests approximately 94% of the time, allowing the Israeli government to censor who and what it wants.

Corporations like Meta also feign willful ignorance about these issues. For example, the independent Human Rights Due Diligence report mentioned above highlighted the lack of appropriate Hebrew Language classifiers, which would enable Meta to moderate Hebrew language content more effectively. However, since the report was published in 2022, Meta has shown no evidence of implementing appropriate Hebrew language classifiers, while plenty of evidence exists to suggest that there are none (or at least not at the scale and level of advancement necessary). As a result, Israelis and their government officials are able to post genocidal rhetoric on the platform.

An August 2024 report by the UN Special Rapporteur on the promotion and protection of the right to freedom of opinion and expression highlighted social media’s contradictory role in Gaza. The platforms have served as “vital” communication channels, allowing Gazans to share information internally and globally, given restricted traditional media access. Young content creators and women in Gaza emerged as important voices documenting realities often absent from mainstream coverage. However, the report found platforms disproportionately removed Palestinian content while inadequately moderating hate speech and allowing misinformation to spread. “The large platforms have tended to be more lenient regarding Israel and more restrictive about Palestinian expression and content about Gaza,” it said.

Watch: Technologies of Genocide | Suchitra Vijayan speaks with Eric Sype and Jalal Abukhater from 7amleh

Disinformation & Propaganda amid Genocide

If the first casualty of war is truth, then Gaza has become its mass grave. For over two years, the genocidal campaign in Gaza has been waged not only with bombs and blockades, but through an information ecosystem hijacked by coordinated disinformation, manufactured narratives, and algorithmic propaganda. Disinformation, in this case, is used as a deliberate tool of erasure, justification, and extermination. This, too, is not a new phenomenon, as Israel has invested in sophisticated disinformation campaigns for years to hide its crimes. Presently, the use of social media has amplified and exacerbated the problem.

The deliberate spread of disinformation during armed conflict, especially when it facilitates war crimes, obstructs humanitarian aid, or incites violence, can itself constitute a violation of international humanitarian law.

Across platforms like Meta, YouTube, and X (formerly Twitter), the world is witnessing a strategic and systemic deployment of falsehoods designed to justify war crimes, silence Palestinian voices, smear humanitarian actors, and shape global public opinion to legitimize mass atrocity. These platforms, driven by profit and political expediency, have not only failed to mitigate this onslaught but have also enabled it.

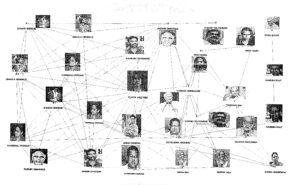

Among the clearest examples is the coordinated disinformation campaign targeting UNRWA, the United Nations agency serving Palestinian refugees. Israel’s government, aided by private digital operatives and platform infrastructure, spread unverified allegations about UNRWA staff, coinciding with high-level Israeli demands to defund the agency. In parallel, the Israeli Ministry for Diaspora Affairs was revealed to be running a covert influence operation through a Tel Aviv-based firm, STOIC. As exposed by Meta’s own threat report and corroborated by OpenAI, this network of fake websites and AI-generated personas targeted progressive lawmakers and Black communities in the US and Canada with content designed to undermine trust in UNRWA and support continued military aggression.

These campaigns had a devastating real-world impact. Within days of the allegations, over a dozen countries froze funding to UNRWA, the largest and most capable humanitarian actor in Gaza. It had drastic financial implications for UNRWA and put its staff in immense danger at a time when many UNRWA workers had already been killed. The defunding occurred at the peak of a man-made famine, when the UN and UNRWA were operating over 400 aid distribution points across the Gaza Strip. In its place, Israel introduced the so-called Gaza Humanitarian Foundation, a military-controlled distribution system widely condemned by humanitarian agencies as a “death trap”. As of writing this, hundreds of Palestinians have been killed, and thousands injured, as Gazans had no other option than to attempt to reach food through these militarized corridors. This transformation of humanitarian aid into a tool of warfare would not have been possible without the digital disinformation that made it palatable to donor states and the international public.

Social media platforms played a central role in circulating and amplifying these narratives. Despite clear indications that the allegations against UNRWA were politically motivated and unsupported by independent investigation, the content remained live, promoted, and monetized. In September 2024, UNRWA’s Commissioner-General Philippe Lazzarini publicly denounced the campaign, stating that Israel not only disseminated falsehoods but also purchased Google ads to dissuade users from donating to the agency. This level of coordination, where a state uses paid advertising infrastructure to dismantle a humanitarian lifeline, represents a new frontier in information warfare.

And this is only one example. From the earliest days of the assault on Gaza, Israeli officials and far-right influencers have used disinformation to incite collective punishment and normalize mass violence. Viral stories, such as the now-debunked claim that Hamas had beheaded 40 babies, were repeated uncritically by Western politicians, including then US President Joe Biden. Fabricated images and AI-generated videos circulated widely, including false claims about hostage children in cages or faked scenes of Palestinian death.

This landscape is further distorted by unequal enforcement. As shown earlier, Palestinian voices are not only censored, but they are often punished for speaking. Meta’s documented reduction of its moderation threshold for Arabic-language content has created a digital regime in which Palestinian speech is presumed guilty. Meanwhile, Israeli officials and soldiers openly post incitement, glorify war crimes, and dehumanize Palestinians, all with impunity.

Under international law, these asymmetries are not minor infractions. The deliberate spread of disinformation during armed conflict, especially when it facilitates war crimes, obstructs humanitarian aid, or incites violence, can itself constitute a violation of international humanitarian law. YouTube, for example, has repeatedly hosted war propaganda advertisements from the Israeli Ministry of Foreign Affairs that urged viewers to support military actions in Gaza. Many of these ads contained inflammatory language, emotional manipulation, and graphic content, disseminated at scale through the platform’s advertising tools, to normalize or encourage collective punishment. When platforms knowingly host, amplify, and profit from such content, they cannot plead neutrality.

The UN Commission of Inquiry has affirmed that Israel’s systematic destruction of civilian infrastructure, including schools, religious sites, and cultural institutions, amounts to war crimes and crimes against humanity. In this context, the amplification of false narratives and silencing of Palestinian voices is not a digital inconvenience; it is part of the apparatus of extermination.

Disinformation is not just about what is said. It is about who gets heard, whose stories are erased, and whose lives are devalued. Meta and other major social media platforms have systematically censored content documenting Israeli violations of human rights, while simultaneously platforming elaborate disinformation campaigns designed to confuse and obfuscate the world’s understanding of what is happening in Gaza. The challenge is not only to expose these systems, but to dismantle them. Platforms must be held accountable not just for content moderation, but for their role in manufacturing consent for Genocide.

Media outlets, from Nazi newspapers to Rwandan radio stations, have been held accountable in court for their role in spreading genocidal rhetoric. There are current efforts underway to hold Meta to account for their role in Myanmar and Ethiopia, and we are at the beginning of similar efforts building for Meta’s complicity in Gaza. It is important to utilize the available legal mechanisms at hand to hold social media to account for its role in Gaza, but we must do more as well.

Big Tech, by and large, still “regulates” itself. The European Union has made important efforts to change this via the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), the Digital Services Act (DSA), and the AI Act. These European regulations are not enough, especially in the global context. Policy makers around the world must take a stronger approach in holding Big Tech accountable. Shareholders, too, should demand that companies take a human rights-centered approach to content moderation via mechanisms afforded to shareholders. There is no single tactic, approach, or regulatory mechanism sufficient to the task. We all must call for accountability, whether we are politicians, shareholders, or simply users of these platforms, or else we will continue to see social media play a more and more devastating role in society.

Related Posts

Algorithmic Politics: How Meta Silenced Palestinian Voices Amid Genocide

The authors of this essay are researchers at 7amleh – The Arab Center for Social Media Advancement, a Palestinian digital rights organization. 7amleh has published extensive reports on Meta’s systematic censorship of Palestinian content, especially during critical periods of conflict and uprising.

The censorship of Palestinian voices is not new, and recent events have thrust this longstanding crisis into global view. As the Gaza genocide unfolded, Palestinians and their allies worldwide found their social media posts about it blocked or shadow-banned. Media outlets, academics, and human rights groups have reported this practice of online suppression for years. Then, the surge in censorship since October 2023 marked an intensification of a troubling pattern, whose roots run deeper.

Ten years ago, a little-known lawsuit against Facebook played a crucial role in setting the foundation for modern power dynamics. It shaped whose voice and perspective can be freely shared on social media, versus which would be suppressed.

In 2015, more than 20,000 Israelis filed a lawsuit against Facebook in the United States, suing the company for $1 Billion due to alleged facilitation and encouragement of Palestinian-led violence against Israeli Jewish citizens. The suit was later dropped, while Facebook publicly announced it would actively partner with the Israeli state to monitor posts by Palestinians. This set the stage for the current digital reality: one where Palestinians are deplatformed for simply posting documentation of human rights violations, while Israeli officials can post openly genocidal rhetoric without consequence.

This dynamic is not unique to the Palestinian context. Amnesty International research detailed how Facebook’s algorithm exacerbated the spread of harmful anti-Rohingya content during the Rohingya genocide in Myanmar in 2017. More recently, in a similar fashion, Meta’s platforms contributed to mass violations of human rights in the Tigray region of Ethiopia. In each context, from Myanmar to Ethiopia, as well as in occupied Palestine, human rights experts have clearly shown Meta’s continual wrongdoing. But not much has changed in its continued practice, showing a lack of intention to change past behavior.

However, May 2021 marked an important turning point when Meta’s biased policies on Palestinians were on display globally. Due to Israeli forces cracking down on Palestinians at Al-Aqsa Mosque and injuring hundreds, and the forced evictions of Palestinian families in the East Jerusalem neighborhood of Sheikh Jarrah, tensions flared and led to the May Uprisings of 2021. During this time, many Palestinians turned to Meta’s social media platforms to post documentation of Israeli human rights violations, particularly surrounding the forced evictions in Sheikh Jarrah, and were met with mass suppression and censorship.

Widespread acknowledgement of the problem led Meta’s Oversight Board to recommend that an independent third party issue a Human Rights Due Diligence report. Over a year later, when the report was finally released, it echoed many of the same points civil societies had been raising for years. It showed that Meta’s content moderation practices and policies were biased against Palestinian and Arabic content, leading to overmoderation and a negative impact on human rights, while likely undermoderating Israeli Hebrew language content. The report also provided 21 recommendations for Meta, of which the company agreed to implement 20, in part or in full. However, one year after the report was released, Meta issued its first progress report, which showed little evidence of progress made on any of the actions. That progress report was released in September of 2023, just weeks before October 7, when Hamas and other Palestinian militant groups carried out incursions in Southern Israel.

Meta’s Biased Algorithm and Content Moderation

In October 2023, with a massive influx of content being posted about Israel and Palestine, especially related to what was happening in Gaza, Meta was caught entirely unprepared (albeit after years of civil society raising the alarm, as well as a two year Human Rights Due Diligence process, all of which leaves one to wonder how much of this incompetence was by design). As a result, Meta took drastic measures and lowered their automated content moderation confidence interval for Arabic language content in Palestine to 40%, and then eventually to as low as 25%. What that means is Meta’s automated systems, which flag and take down content it believes to be violating the platform’s policies, only needed to be 25% confident that a piece of content was violative to take it down, and all without any human moderator acting in the process. This led to massive censorship and suppression of the Palestinians’ freedom of expression, and also directly impacted what people around the world were able to see coming out of Palestine online. Meanwhile, Israeli government, military officials, and community leaders were able to freely post genocidal and racist rhetoric, advocating for the collective punishment of all Palestinians. The juxtaposition was jarring, and once again, many around the world took notice.

In December 2023, Rabbi Moshe Ratt, influential among Israeli settlers in the West Bank, composed a long post on Facebook, which was accessed by The Polis Project. An article in The Conversation noted this post for its advocacy of genocide. Ratt had claimed that some people might have struggled in the past with the question of destroying an entire people, including women and children, but they didn’t face this dilemma anymore. In a reference to Palestinians as “Amalek” (the enemy of Israelites as per the Hebrew Bible), he added, “There are peoples who have reached such a depth of evil and corruption that there is no other way but to wipe them out of the world without a trace [translated by Google].”

In another instance in September 2023, Al Jazeera Arabic presenter Tamer Almisshal’s Facebook profile was deleted by Meta a day after the airing of his programme that investigated Meta’s censorship of Palestinian content.

At the end of 2024, 7amleh (The Arab Center for the Advancement of Social Media), with which the writers of this piece are associated, published a report on Meta’s censorship by documenting testimonies of 20 Palestinian influencers, journalists, and media outlets. Users described deleted posts, suspended accounts, and restricted reach, resulting in economic losses, professional damage, trauma, and violations of digital rights.

Adnan Barq, a Jerusalem-based journalist with 285,000 Instagram (now owned by Meta) followers, was mentioned in the report. He said Meta restricted his ability to share Palestinian stories from Gaza. On October 7, 2023, he was banned from Instagram Live despite posting nothing about the events. When Barq later used Instagram’s collaboration feature to amplify Gazans’ voices, he was blocked after two posts. A Meta employee later admitted the restrictions were “a mistake,” Barq said, but other restrictions persisted. His story views plummeted from 20,000-30,000 before the war to just 3,000-7,000 after. “I started receiving many messages from friends and acquaintances asking why I stopped posting on Instagram,” Barq recalled. “I was surprised by that because I was posting all the time, but it turned out that my content was not reaching them.” The shadow-banning cost him brand collaborations and income.

This brief telling of how Meta has evolved to moderate speech about Israel and Palestine over the years points to larger dynamics across online platforms, which allow for an intentional manipulation of global understandings around what is happening in the region. The state of Israel has a vested interest in this, as illustrated by its tens of thousands of voluntary takedown requests to Meta each year. Meta, even without having any legal obligations, abides by these requests approximately 94% of the time, allowing the Israeli government to censor who and what it wants.

Corporations like Meta also feign willful ignorance about these issues. For example, the independent Human Rights Due Diligence report mentioned above highlighted the lack of appropriate Hebrew Language classifiers, which would enable Meta to moderate Hebrew language content more effectively. However, since the report was published in 2022, Meta has shown no evidence of implementing appropriate Hebrew language classifiers, while plenty of evidence exists to suggest that there are none (or at least not at the scale and level of advancement necessary). As a result, Israelis and their government officials are able to post genocidal rhetoric on the platform.

An August 2024 report by the UN Special Rapporteur on the promotion and protection of the right to freedom of opinion and expression highlighted social media’s contradictory role in Gaza. The platforms have served as “vital” communication channels, allowing Gazans to share information internally and globally, given restricted traditional media access. Young content creators and women in Gaza emerged as important voices documenting realities often absent from mainstream coverage. However, the report found platforms disproportionately removed Palestinian content while inadequately moderating hate speech and allowing misinformation to spread. “The large platforms have tended to be more lenient regarding Israel and more restrictive about Palestinian expression and content about Gaza,” it said.

Watch: Technologies of Genocide | Suchitra Vijayan speaks with Eric Sype and Jalal Abukhater from 7amleh

Disinformation & Propaganda amid Genocide

If the first casualty of war is truth, then Gaza has become its mass grave. For over two years, the genocidal campaign in Gaza has been waged not only with bombs and blockades, but through an information ecosystem hijacked by coordinated disinformation, manufactured narratives, and algorithmic propaganda. Disinformation, in this case, is used as a deliberate tool of erasure, justification, and extermination. This, too, is not a new phenomenon, as Israel has invested in sophisticated disinformation campaigns for years to hide its crimes. Presently, the use of social media has amplified and exacerbated the problem.

The deliberate spread of disinformation during armed conflict, especially when it facilitates war crimes, obstructs humanitarian aid, or incites violence, can itself constitute a violation of international humanitarian law.

Across platforms like Meta, YouTube, and X (formerly Twitter), the world is witnessing a strategic and systemic deployment of falsehoods designed to justify war crimes, silence Palestinian voices, smear humanitarian actors, and shape global public opinion to legitimize mass atrocity. These platforms, driven by profit and political expediency, have not only failed to mitigate this onslaught but have also enabled it.

Among the clearest examples is the coordinated disinformation campaign targeting UNRWA, the United Nations agency serving Palestinian refugees. Israel’s government, aided by private digital operatives and platform infrastructure, spread unverified allegations about UNRWA staff, coinciding with high-level Israeli demands to defund the agency. In parallel, the Israeli Ministry for Diaspora Affairs was revealed to be running a covert influence operation through a Tel Aviv-based firm, STOIC. As exposed by Meta’s own threat report and corroborated by OpenAI, this network of fake websites and AI-generated personas targeted progressive lawmakers and Black communities in the US and Canada with content designed to undermine trust in UNRWA and support continued military aggression.

These campaigns had a devastating real-world impact. Within days of the allegations, over a dozen countries froze funding to UNRWA, the largest and most capable humanitarian actor in Gaza. It had drastic financial implications for UNRWA and put its staff in immense danger at a time when many UNRWA workers had already been killed. The defunding occurred at the peak of a man-made famine, when the UN and UNRWA were operating over 400 aid distribution points across the Gaza Strip. In its place, Israel introduced the so-called Gaza Humanitarian Foundation, a military-controlled distribution system widely condemned by humanitarian agencies as a “death trap”. As of writing this, hundreds of Palestinians have been killed, and thousands injured, as Gazans had no other option than to attempt to reach food through these militarized corridors. This transformation of humanitarian aid into a tool of warfare would not have been possible without the digital disinformation that made it palatable to donor states and the international public.

Social media platforms played a central role in circulating and amplifying these narratives. Despite clear indications that the allegations against UNRWA were politically motivated and unsupported by independent investigation, the content remained live, promoted, and monetized. In September 2024, UNRWA’s Commissioner-General Philippe Lazzarini publicly denounced the campaign, stating that Israel not only disseminated falsehoods but also purchased Google ads to dissuade users from donating to the agency. This level of coordination, where a state uses paid advertising infrastructure to dismantle a humanitarian lifeline, represents a new frontier in information warfare.

And this is only one example. From the earliest days of the assault on Gaza, Israeli officials and far-right influencers have used disinformation to incite collective punishment and normalize mass violence. Viral stories, such as the now-debunked claim that Hamas had beheaded 40 babies, were repeated uncritically by Western politicians, including then US President Joe Biden. Fabricated images and AI-generated videos circulated widely, including false claims about hostage children in cages or faked scenes of Palestinian death.

This landscape is further distorted by unequal enforcement. As shown earlier, Palestinian voices are not only censored, but they are often punished for speaking. Meta’s documented reduction of its moderation threshold for Arabic-language content has created a digital regime in which Palestinian speech is presumed guilty. Meanwhile, Israeli officials and soldiers openly post incitement, glorify war crimes, and dehumanize Palestinians, all with impunity.

Under international law, these asymmetries are not minor infractions. The deliberate spread of disinformation during armed conflict, especially when it facilitates war crimes, obstructs humanitarian aid, or incites violence, can itself constitute a violation of international humanitarian law. YouTube, for example, has repeatedly hosted war propaganda advertisements from the Israeli Ministry of Foreign Affairs that urged viewers to support military actions in Gaza. Many of these ads contained inflammatory language, emotional manipulation, and graphic content, disseminated at scale through the platform’s advertising tools, to normalize or encourage collective punishment. When platforms knowingly host, amplify, and profit from such content, they cannot plead neutrality.

The UN Commission of Inquiry has affirmed that Israel’s systematic destruction of civilian infrastructure, including schools, religious sites, and cultural institutions, amounts to war crimes and crimes against humanity. In this context, the amplification of false narratives and silencing of Palestinian voices is not a digital inconvenience; it is part of the apparatus of extermination.

Disinformation is not just about what is said. It is about who gets heard, whose stories are erased, and whose lives are devalued. Meta and other major social media platforms have systematically censored content documenting Israeli violations of human rights, while simultaneously platforming elaborate disinformation campaigns designed to confuse and obfuscate the world’s understanding of what is happening in Gaza. The challenge is not only to expose these systems, but to dismantle them. Platforms must be held accountable not just for content moderation, but for their role in manufacturing consent for Genocide.

Media outlets, from Nazi newspapers to Rwandan radio stations, have been held accountable in court for their role in spreading genocidal rhetoric. There are current efforts underway to hold Meta to account for their role in Myanmar and Ethiopia, and we are at the beginning of similar efforts building for Meta’s complicity in Gaza. It is important to utilize the available legal mechanisms at hand to hold social media to account for its role in Gaza, but we must do more as well.

Big Tech, by and large, still “regulates” itself. The European Union has made important efforts to change this via the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), the Digital Services Act (DSA), and the AI Act. These European regulations are not enough, especially in the global context. Policy makers around the world must take a stronger approach in holding Big Tech accountable. Shareholders, too, should demand that companies take a human rights-centered approach to content moderation via mechanisms afforded to shareholders. There is no single tactic, approach, or regulatory mechanism sufficient to the task. We all must call for accountability, whether we are politicians, shareholders, or simply users of these platforms, or else we will continue to see social media play a more and more devastating role in society.

SUPPORT US

We like bringing the stories that don’t get told to you. For that, we need your support. However small, we would appreciate it.