Patterns of Erasure: How India’s Mosques and Islamic Shrines are Systematically Targeted

In the heart of India’s national capital, Delhi, a few men gather at a tea stall and debate petitions filed against mosques. One insists it’s time “the old glory of Hinduism is returned.” Another recalls that the Mughal rulers “destroyed so many monuments.” These everyday conversations echo a larger project: a campaign to erase India’s Islamic sites under the Bharatiya Janata Party’s rule.

In recent years, mosques, madrassas, tombs, and mazars—shrines built over the graves of revered Muslim saints—have been razed, fenced off, or dragged to court. The right-wing Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), in power of the federal government and in several states, has been on an increasing demolition spree. With the use of the bulldozer, which has become a ‘symbol’ of anti-minority rhetoric, there is a growing trend to bring down Islamic religious structures in an ongoing attack on the Indian Muslim community.

In August 2025, a Hindutva (right-wing, Hindu supremacist) group with raised saffron flags broke through the police barricades in Uttar Pradesh’s Fatehpur to enter a mausoleum (maqbara), claiming it to be a 200-year-old Hindu Thakur temple.

It brings up flashbacks of the Babri Mosque demolitions of 1992, which propelled the BJP to political prominence. In Fatehpur, the mob was seen holding saffron flags and running through the streets. Despite a heavy presence of the Provincial Armed Constabulary and the police, people were able to cross the police blockade and reach the mausoleum. They were seen climbing up the structure and destroying parts of the tomb while shouting slogans of ‘Jai Shree Ram’ (glory to Lord Ram).

The targeting of Muslim heritage sites is not merely about contested land or architectural relics; it reflects a broader attempt to rewrite India’s pluralistic history, delegitimise Muslim presence, and homogenize the cultural landscape in accordance with a Hindu majoritarian narrative.

The deliberate demolition or contestation of these Islamic structures by invoking legal mechanisms, public mobilisation, or state machinery is often done under the garb of reclaiming ‘Hindu heritage’. This form of erasure disrupts not only physical sites but also the memory and effective histories tied to them; it hollows out the pluralism that such spaces historically nurtured.

French political scientist and historian Christophe Jaffrelot, in his book Modi’s India, examines the broader project of India’s Hinduization, transforming a secular nation-state into a champion of the “ethnic nationalism” of far-right Hindus. Jaffrelot frames Hindu nationalism as a system where the dominant group—Hindus—defines the nation through cultural and religious identity, which fosters a sense of superiority and excludes Muslims. This model thrives on a perceived threat from minorities, and that in turn, is used to justify majoritarian mobilization.

In India, Muslims are increasingly portrayed as internal enemies, leading to their marginalization and persecution. While noting the incongruence of democracy with such “ethnic nationalism”, Jaffrelot writes: “…Modi’s India, during NDA II, can be said to have invented a de facto ethnic democracy, a political system in which the state remained relatively in the background, leaving the field open to vigilante groups, which, with the tacit or explicit support of law enforcement bodies, went after “deviants,” whether they were champions of secularism or members of minorities.”

Whether it’s the official turn towards calling India “Bharat”, or the prime minister’s fear-mongering about Muslims during election campaigns, or the many organs of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) rallying against mosques and other religious structures, the said Hindu nationalist or Hindutva project is in motion. Against this backdrop, the multi-pronged efforts to remove Islamic sites appear as part of a sustained project of cultural majoritarianism.

Attack on Religious Institutes

Since 2014, when the BJP government came to power, India’s 200 million minority Muslims have been subjected to persecution, violence, and discrimination. Under the banner of Hindutva (Hindu nationalist), which aims to establish India as a Hindu nation, rather than a secular state, Muslim civilians, activists, and journalists have been routinely targeted. There has also been a move to boycott Muslim-owned businesses, target Muslim places of worship, and use Islamophobic rhetoric by BJP leaders, while the lynching of Muslims has been on the rise.

Amid this climate, mosques and mazars have increasingly been marked for legal challenges or demolition. In early October this year, the Supreme Court of India upheld the partial demolition of a 400-year-old mosque complex in Ahmedabad, Gujarat. The ruling allowed for the clearing of an adjoining platform and the obtaining of land for a road-widening project, while the main structure would remain intact.

Authorities in several states have also cited “encroachment” laws to justify mosque and mazaar demolitions, yet similar scrutiny has not been applied to other structures in the same areas. This selective enforcement has fueled concerns that these efforts are part of a broader ideological push to redefine India’s historical and religious landscape through the lens of Hindutva.

The Polis Project investigated the legal petitions filed against the mosques, the demolitions of mosques and mazars, the individuals and groups behind these efforts, and the patterns of violence and disputes that have arisen in the name of historical reclamation.

The Babri Blueprint to Recast India’s Religious Landscape

The pattern of demanding erasure of mosques based on contested history can be traced back to the Ram Janambhoomi movement, led by veteran BJP leader LK Advani. It was a political rally travelling across much of northern India to Ayodhya, a town in Uttar Pradesh.

The campaign sought to generate support for a proposed Ram Temple at the site of the Babri Mosque. It ended in the demolition of the 16th-century mosque by a Hindu mob in 1992. It gave rise to communal violence across India and eventually propelled a wave of popularity for the BJP, bringing it to power in 1998. The mosque had been constructed by the Mughal Emperor Babur. The dispute centered on the claim that a Hindu temple lay underneath it, and it was believed to be the birthplace of Rama, a Hindu mythological figure and deity.

The trend has traversed decades to survive and flourish under the Narendra Modi-led government. In 2025 alone, several incidents of mosque and mazaar demolitions have been reported.

In March this year, Mughal emperor Aurangzeb’s tomb in Maharashtra’s Chhatrapati Sambhajinagar had to be put under heavy security after Hindu outfits like Vishwa Hindu Parishad and Bajrang Dal threatened a “Babri Masjid-like fate” if their demand to remove the structure was not met by the state government. VHP and Bajrang Dal members also staged a protest in front of the Nagpur District Collector’s office over their demand to remove Aurangzeb’s tomb. Hours after, clashes erupted amid rumours that a cloth bearing the Islamic declaration of faith, or Kalma, had been burned during the protest, prompting stone-pelting at the police. This eventually led to the arrest of around 100 people, including several Muslims.

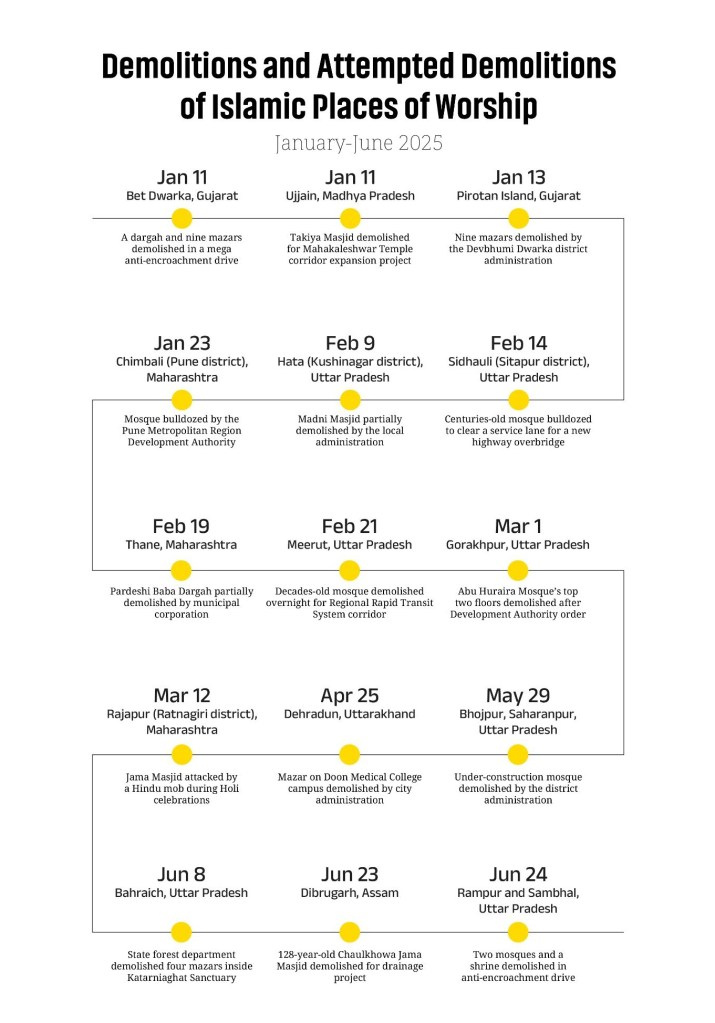

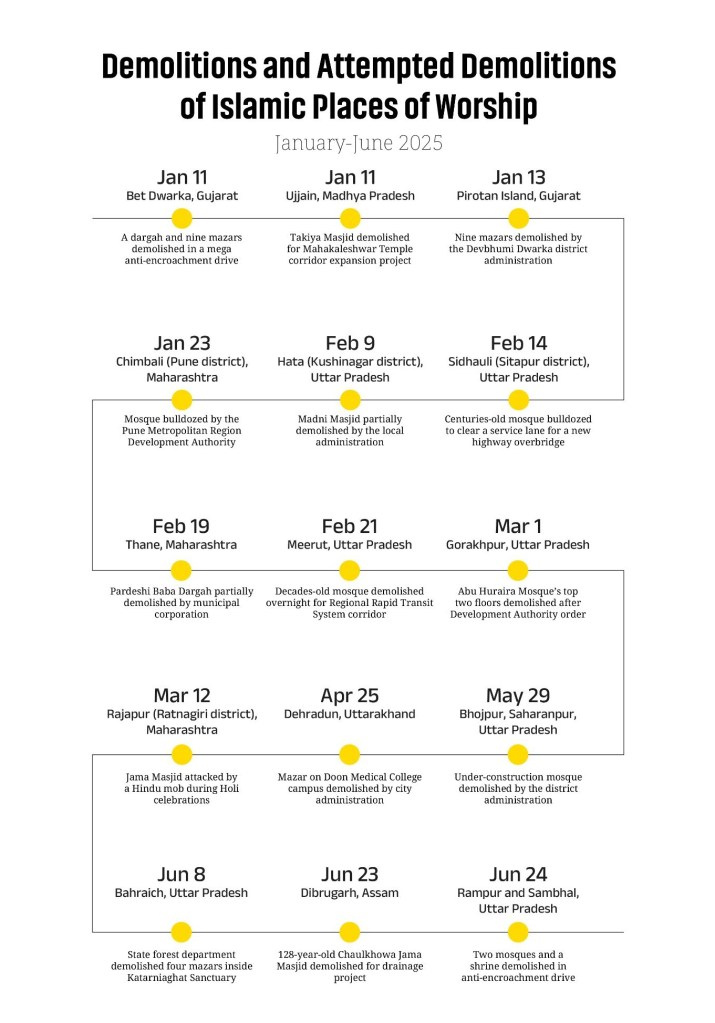

The spate of mosque and mazar demolitions across India in early 2025 — from Bet Dwarka and Ujjain to Bahraich and Dibrugarh — reflects a distinct pattern of religious structures being targeted by encroachment drives. There is no concrete data available for incidents of mosque demolition or attempts at the same. To present a rough idea of the scale, The Polis Project recorded 15 cases from media reports in the first six months of 2025.

Certain areas in the country have turned into hotbeds of tension between Hindu and Muslim communities over mosque disputes. Sambhal, a historically significant district in the northern state of Uttar Pradesh, has remained on edge for over a year. In October this year, a mosque in the village of Raya Buzurg in Sambhal was demolished after the Allahabad High Court dismissed a petition seeking a stay. Authorities said it stood illegally on reserved pond land.

It is noteworthy that the Uttar Pradesh government is led by firebrand BJP leader and Hindu nationalist Yogi Adityanath, who is known for using the bulldozer against the Muslim community in incidents of punitive demolitions, which have been extensively reported by The Polis Project.

In 2024, a dispute erupted over the 16th-century Mughal-era Shahi Jama Masjid in Sambhal after Hindu groups claimed the mosque stood on the remains of an ancient temple.

On 24 November 2024, a team from the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI), the state agency for conservation of cultural and historical monuments, arrived to survey the Shahi Jama Masjid, accompanied by a group of Hindu right-wingers.

The survey was done in the wake of a petition filed by advocate Hari Shankar Jain, who challenged the mosque committee’s claim that it was responsible for the mosque’s maintenance under a 1927 agreement, arguing that the responsibility lay with the ASI.

While delivering its order, Jain requested the bench to refer to the mosque as a “disputed structure,” and the court agreed.

On the day of the survey, violence erupted when rumours spread that ASI officials were demolishing an old well inside the mosque, and this made many of the locals angry. In retaliation, police fired shots at unarmed protesters, killing six.

One of those killed was Naeem, a 35-year-old resident of Sambhal and a tailor by profession. He was killed by a bullet that hit his chest.

Months later, Idreesa, his mother, continued to reel from the sudden loss of her son. She sat in her small house near the Shahi Jama Masjid, speaking to these reporters. In moments between the conversation, she clutched her chest as if in pain, with tears pooling in her eyes. “My son is gone, my son is gone,” she said.

According to historians and locals alike, Sambhal has always been a place of conflict. During the conversations with locals from both the Hindu and the Muslim communities, different versions of history can be heard.

Among the Muslim locals, a gruesome story travels: On one fateful night during Shivratri, a Hindu festival dedicated to Lord Shiva, a Hindu mob entered the Jama Masjid in Sambhal, tied the Maulana, and slit his throat during the 1976 communal violence.

“His blood was splashed all over the mosque,” Areeba, a local woman who lives near the mosque, said, recalling the event.

After the violence and a month-long curfew, Sambhal became a communally sensitive hotspot. Another riot broke out in 1978, wherein the Parliament considered sending a team to the tiny town on a fact-finding mission.

But what made the Shahi Jama mosque a place of conflict? Hindus believe that Sambhal is the place where the Hindu god Kalki would be born. The ‘satya yug’ or the golden age, according to Hinduism, is supposed to start in Sambhal with Kalki’s birth. “We are proud to be born at a place where Lord Kalki’s birth will take place,” Rajesh Kumar, a resident of Sambhal, said.

With such stories and incidents shaping both the communities, the tensions, which Sambhal has witnessed in 1976, 1978, and 1992 ( right after the demolition of Babri Masjid), have resurfaced. But locals said, barring these years, the small town has usually been quiet, until 2024.

The claim of dispute around Shahi Jama Masjid was also based on a court case that claimed the mosque was built on the site of Harihar Mandir, where Kalki is supposed to be born.

How Mosques Became Political Targets

Most of the mosques, against which petitions are filed, were built during the Mughal era. This, however, cannot be said about mazars and other Islamic structures.

Several experts believe the Mughal structures are targeted deliberately, as it helps create a historical “other” against the Hindu “self”.

Ghazala Jamil, Assistant Professor at the Centre for the Study of Law and Governance in Delhi’s Jawaharlal Nehru University, said the focus on the Mughals by Hindutva groups is not random and can be explained through several “overlapping reasons”.

“The Mughal Empire has a quick recall value and is more visible in India’s public culture than earlier Muslim dynasties because of its lasting monuments, like the Taj Mahal which has come to represent India itself in the world’s imagination, or the Red Fort which became a symbol of India’s sovereignty,” she explained.

According to Jamil, another reason is that Mughal rule was relatively stable over a long period. Mughals remained in power, even if only notionally, right up to the mid-19th century, which makes it easier for people to recall and imagine it compared to older, less unified kingdoms. “At the same time, British colonial historians had already framed a part of Indian history as a story of Hindu decline under Muslim rulers, which Hindutva groups find simple and handy for their own purposes. This ready-made story paints the Mughals as foreign occupiers, making them a convenient target for a politics that seeks to reclaim an imagined pure Hindu past,” she added.

Losing a Past of Religious Harmony

Unlike mosques, places like mazars have long played a significant role in cultural integration and harmony.

Rana Safvi, an Indian historian and writer who has worked on the documentation of mosques and mazars of India, told The Polis Project that historically, both mosques and mazars have played significant roles as a cultural and spiritual space for not just Muslims but also other communities.

“In both Delhi and Uttar Pradesh, between 1947 and 1957, there was an influx of partition refugees. And it is at mazars and tombs that these refugees stayed. They were desperate for a place to live in and many of them stayed wherever they could, so these monuments became a place of refuge. I call this a tragedy, because this led to the erasure of many such places,” she said.

In all of this, one cannot rule out the role of the Mughals in constructing these magnificent monuments and marking parts of India’s history in stone, many of which are now being targeted for that very same reason.

In her blog post, Safvi says Delhi became the hotspot for Mughals to construct various monuments after they declared their capital. Delhi, which was once known as Shahjahanabad—after Mughal Emperor Shah Jahan who built it in 1639—and home to several fifth and sixth generation residents, all of whom Safvi describes as “keepers of its history.”

The city today, she says, is far removed from the vision of its chief architect. “Shah Jahan was a prolific builder. When he gave orders to build a new city, he envisaged a magnificent place on the theme of paradise, built on the banks of the River Yamuna. It was also a planned city with specific areas allocated according to trade, profession and hierarchy. Land was allotted for havelis, gardens, bazaars and religious buildings. This city bore the brunt of the revolt of 1857 when the British looted the nobility, banished residents and rearranged the city for administrative purposes,” she said.

A Long Thread of Demolition Politics

Despite its importance, the Babri Mosque was not the start of the “demolition politics” as we have come to know today. In the book, Hindu Temples: What Happened to Them, written by Sita Ram Goel, Arun Shourie, Harsh Narain, Jay Dubashi, and Ram Swarup, there exists a list of such structures and monuments in India that several groups want demolished. The book mentions a list prepared by the Hindu Mahasabha that has been in circulation for long and, at the time of the book’s publication in 1990, the tally stood at 880.

These 880 monuments, established by Muslims, are not just mosques but include idgahs, imambaras, baradaris, cemeteries, and graves of Sufi saints. The largest chunk of these, roughly 281, are graves and mazars of Sufi saints and common Muslim cemeteries. However, in India, they are a place of cultural integration, with people from different religious backgrounds coming together to witness traditions that were once celebrated and pray for things.

In her book The Sufi Courtyard: Dargahs of Delhi, Sadia Dehlvi narrated how these places, often described as the “origins of Sufism” have a cultural significance. “This city (Delhi)”, she says, “has always been an important centre of the different Sufi orders called silsila. Delhi’s inclusive culture ensures that though Chishtis are the dominant order here, other orders such as Suharwardis, Qadris and Naqshbandis continue to have a presence.”

Media reports and research show the number of mazars being attacked has increased significantly, wherein self-styled Hindutva activists have taken it upon themselves to take the law into their own hands and demolish mazars. Many mazars have been demolished in Himachal Pradesh in the past year. Such structures are also destroyed under “encroachment” allegations. However, it is extremely difficult to find conclusive data on this.

In his article, Babri Masjid and the politics of demolition, activist and scholar Ali Fraz Rezvi writes, “There have been several instances when mazars and graves were either attacked by a mob or demolished on the orders of the government. They include the demolition of seven mazars in UP’s Mathura in 2018, ordered by the Adityanath government, the one in Barabanki in 2021, and the mazar between Chaubepur and Shivajipur, Kanpur, in 2022, by government authorities, and the vandalisation of the mazars of Jalal Shah, Bhureshah, and Qutubshah in Bijnor.” Rezvi goes on to add that “Similar cases were reported in Gujarat and Uttarakhand as well. The year 2022 alone has reportedly witnessed the demolition of more than 12 mazars.”

In November 2022, Home Minister Amit Shah stated that “fake mazars” have been cleared from Gujarat as part of the BJP-led State government’s “clean-up” policy. He has also, on various occasions, emphasized that mazars and graves were illegal encroachments and thus would be removed.

Amid this, what is lost are places of mystic traditions and cultural gatherings. In Delhi, for example, the Mandi House mazar, which was demolished by civic authorities in April 2023, was where the national capital’s theatre scene buzzed. Hundreds of star-glazed theatre artists sat by the mazar drinking tea and talking about art, films, and politics. But now, instead of the mazar, there is a piece of modern architecture with shiny lights blending the space into generic urban scenery.

The dargah, which was demolished, was known popularly as the Nanhe Mian Chishti Dargah and is known to be two centuries old. For as long as anyone who has lived in Delhi can remember, the dargah has been a part of their existence.

This is not the only case. A demolition drive between 2023 and 2024 in Delhi razed more than 15 dargahs. As per media reports, in the same period, the Uttarakhand government bulldozed more than 300 mazars in the state. Vigilantes associated with Hindutva groups, like Dev Bhoomi Raksha Ahbyan, continue vandalising and destroying Muslim religious sites in the state.

Many dargahs have been demolished in Uttar Pradesh as well. Safvi calls it an “erasure of history”.

An Aligarh Muslim University scholar, Zainab, who has studied the history and art of Islamic structures, said that despite their research on mazars, these remain ignored structures and their obliteration often fail to attract much attention. “I myself have come across so many news reports of a dargah getting demolished but did not pay any attention. In Aligarh itself, mazars have been demolished,” she said.

Other Historical Disputes

In June 2021, Pandit Keshav Dev Gautam, a self-styled ‘anti-corruption activist’ and national Chief of Bhrashtachar Virodhi Sena (BVS), filed a petition with the Municipal Corporation of Aligarh under the Right to Information Act, demanding information about the Jama Masjid of Aligarh.

He claimed that the response revealed the mosque was constructed on “Public Land,” though the Aligarh Municipal Corporation had already dismissed those claims. Following the response from the municipal corporation, he also wrote to the district magistrate demanding demolition of the mosque.

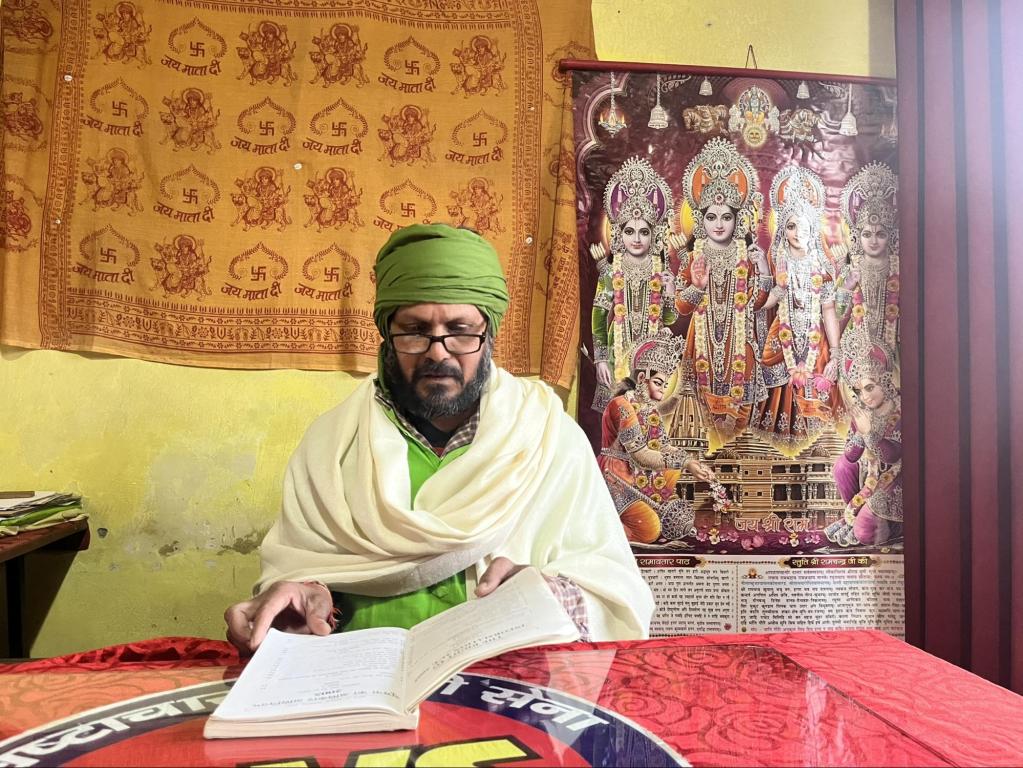

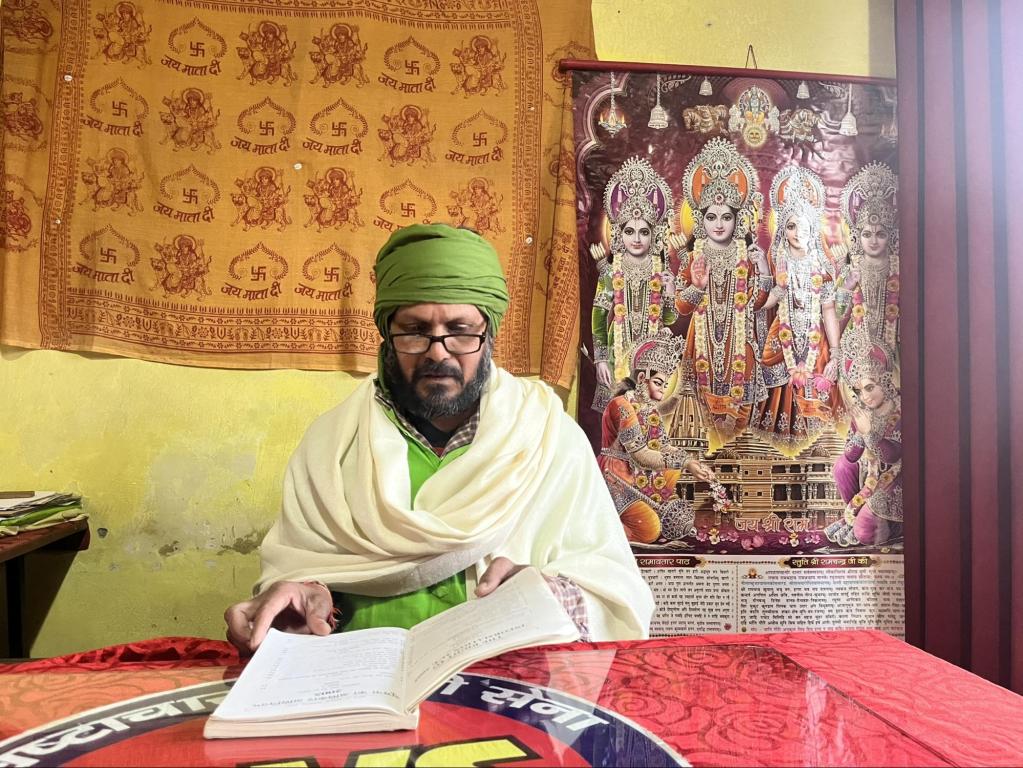

The Polis Project met with Gautam in his small office attached to his house in Aligarh. Wearing a checked shirt and wrapping a green cloth on his head, Gautam introduced himself as a ‘pandit’ and an ‘activist’.

Gautam is not originally from Aligarh; he is not even from Uttar Pradesh, but a resident of Haryana who migrated here two decades back.

He started filing Right to Information (RTIs) that led him to believe that one of India’s oldest mosques was constructed on the periphery of a Shiv Temple. While hinged on fighting corruption, Gautam’s ideology resembles what is propagated by religious right-wing organisations. However, he is not a part of the VHP or Bajrang Dal, who are, most of the time, behind such claims of dispute.

“I have no issues with them [Muslims], but we cannot deny the Mughals made an empire by destroying Hindu structures. I just want accountability,” he said.

Further, in January 2025, Gautam filed another petition in the Aligarh district court, alleging the Jama Masjid was illegally built over a Shiva temple. He cited Jahangirnama (1610-17) to claim that Sidha Khan, a Mughal-era ruler of Aligarh, built the Jama Masjid on public land.

However, experts said that Sidha Khan governed during Mughal ruler Aurangzeb’s reign (1658-1707), making such a reference in the Jahangirnama historically dubious. When asked, Gautam revised his claims, revealing inconsistencies.

“There was no [Jama] Masjid in 1753 during Raja Surajmal’s time,” he asserted. However, historical records show that construction began in 1724 under Sabit Khan, Governor of Kol, during Muhammad Shah’s reign (1719-1728), and was completed in 1728. Sabit Khan’s grave still lies 700 meters from the mosque.

In 1740, Reja Muhammad’s Persian account, Akhbar-ul-Jamal, documented that the Jama Masjid, built by Sabit Khan, spanned 4,004 square yards at that time.

Gautam also claimed this was not a “Hindu-Muslim” issue, but that “those people” have encroached on the shops outside the masjid.

However, experts told The Polis Project that this information is distorted. Senior Professor of History at Aligarh Muslim University, Syed Ali Nadeem Rezavi, who also serves as the secretary of the Indian History Congress, said, “The mosque does not belong to Jahangir’s period at all. There may have been several mosques, including structures in the old city of Kol and the Upperkot area, which date back to the early Sultanate period.” Additionally, there is a tomb from Mughal ruler Babur’s era, along with structures built under Muslim rulers like Khilji and Tughlaq.

Rezavi explained that Aligarh, in ancient times, was known as Kol, named after a demon who was killed by the brother of Lord Krishna, Balarama, according to Hindu legends.

“Let us not delve into history. The Supreme Court upheld the Places of Worship Act of 1991. However, the issue lies with lower courts admitting petitions that undermine this ruling to bully the minorities of the country,” Professor Rezavi said.

On the other hand, Gautam claimed that the issues he raised were supported by the Rashtrawadi (nationalist) and Dharmaic (religious) factions. “The court has not prohibited us from filing petitions. It is not a Mandir-Masjid dispute. It is about how Muslims have illegally occupied the structure,” he said.

Aligarh’s Jama Masjid is no ordinary mosque. It is one of the oldest surviving Mughal mosques in the country. It was declared a protected monument in 1920 and has remained so since.

Gautam is demanding that the “encroachers” be thrown out immediately and that all illegal construction be demolished. He alleged that the shops are benefiting the masjid committee, which in reality, is an unofficial organisation started by people from within the community.

The Polis Project reached out to the masjid committee, who refused to comment on the court matter and said they are “taking legal help”. They further claimed that the self-acclaimed activist is trying to stir communal tensions that “do not exist”.

Although the Supreme Court has put a stay on the petition, it has opened the mosque to scrutiny with the right-wing groups, forming committees to look into the matter and reach out to the court again.

Legal Loopholes

In 2022, during the hearing of the Gyanvapi Mosque petition, former Chief Justice of India DY Chandrachud, made an oral observation stating that Sections 3 and 4 of the Places of Worship Act, 1991, do not prohibit the “ascertainment of religious character” of any place of worship.

This observation had serious repercussions at the lower judiciary with a number of districts and sessions courts, especially in Uttar Pradesh and Rajasthan, admitting petitions seeking to “ascertain the religious character” of mosques and other places of worship built in medieval India and ordering their surveys.

Among the places facing calls for survey are the Ajmer Dargah, Adhai Din ka Jhonpra, the Shahi Jama Masjid in Sambhal, the Teelewali Masjid in Lucknow, the Shamsi Jama Masjid in Badaun, the Atala Masjid in Jaunpur, including the famous cases of Gyanvapi Masjid, the Eidgah in Mathura and Kamal Maula Masjid in Dhar.

The Places of Worship (Special Provisions) Act, 1991, freezes the religious character of all places of worship as it existed on August 15, 1947. This Act prohibits any conversion of a place of worship to a different religious denomination or even within the same denomination. It also prevents courts from entertaining any disputes regarding the religious character of places of worship as it existed on August 15, 1947. However, the Ayodhya site is an exception in this matter.

According to official documents accessed by The Polis Project, there are, as of now, 58 mosques that are under dispute.

Speaking to The Polis Project, Supreme Court Advocate Ali Zaidi said that the loophole left by former Chief Justice DY Chandrachud is being used by these groups to file civil suits and make these sites disputed property.

“They say that it is not a mosque at all. Even if you read the High Court judgement of this Shahid Jahan Masjid in Ayodhya. You are now using a different strategy altogether to circumvent it and courts are accepting it,” Zaidi said.

Instead of shutting down the controversy altogether, the former CJI left this caveat in his Babri judgement, which has led to multiple civil suits, including that of Sambhal, claiming these Islamic places are not religious sites.

What Gautam did was file a petition on the information he got through Right to Information (RTI). This is part of a pattern of filing RTIs and trying to relate the information to distorted historical facts.

“To prove a site is disputed you have to prove a prima facie to show the same. For that you have to have some material. For that purpose, I file an RTI and ask a vague question, which will suit my intent,” Zaidi explained.

According to an affidavit submitted to the Supreme Court in a plea to uphold the constitutional validity of the Places of Worship (Special Provisions) Act of 1991, 11 mosques in India are facing a total of 18 lawsuits from Hindu outfits, which claim them to be temples.

On 12 December 2024, the Supreme Court of India directed trial courts across the country not to pass any effective orders or surveys against existing religious structures in suits filed disputing the religious character of such structures until the apex court decides on the constitutional validity of the Places of Worship (Special Provisions) Act.

The Bench also directed that “in pending suits, the courts would not pass any effective interim orders or final orders including orders of survey till the next date of hearing”.

In the disputed cases, seven out of the 11 mosques are in Uttar Pradesh, with one each in Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan, Karnataka, and New Delhi.

Disputed, Contested, and Erased

An analysis of 25 targeted mosques across the country shows that 13 are clearly ASI-protected, one is a historically significant but non-protected structure, and another falls under enemy property regulations.

Additionally, according to a Waqf volunteer who requested anonymity, 38 mosques and religious structures in Delhi alone have been targeted in legal or administrative proceedings.

In conflicts involving ASI-protected mosques, many of the disputes center around restrictions on worship and access. For instance, at the Quwwat-ul-Islam Mosque in Delhi, worship is not permitted due to the ASI’s conservation rules. Legal battles frequently arise over ownership and status, with petitions seeking to determine whether these mosques should be treated as religious sites or historical structures.

In several cases, ASI surveys have been demanded to examine the origins of these mosques, especially where claims exist that they were built over pre-existing Hindu temples.

The Gyanvapi Mosque in Varanasi, Uttar Pradesh, is another example that has been the subject of legal disputes, with petitions calling for an ASI survey to investigate its origins. Similarly, in Mathura, Hindu groups have pushed for an ASI survey of the Shahi Idgah Mosque, citing its proximity to the Krishna Janmabhoomi temple.

Immamur Rehman, Assistant Secretary at the Jamaat-e-Islami Hind Headquarters, said mosque committees are facing difficulties despite having proper documents. He added that in the case of Gyanvapi, the mosque committee had “sufficient records and literature of those times which they submitted all in the court.”

“Going to Gyanvapi is not very easy now. It is surrounded on all sides with barricades and checkpoints for prayers, no phones, no electronics and all around it there is a temple where there is free access, people are coming and going, all the roads that lead to the mosque are also theirs, such an atmosphere has been created that if one gate of the mosque is closed, going to the mosque will be stopped,” Rehman observed.

These disputes often become politically and communally sensitive, with right-wing groups advocating for the “liberation” of certain mosques. This has led to court cases, religious mobilization, and heightened tensions. ASI and local authorities sometimes undertake restoration work that alters structures or results in restricted access, further complicating these disputes.

Atala Masjid in Jaunpur, Kamal Maula Masjid in Dhar, and Adhai Din Ka Jhopra in Ajmer have all been at the center of debates regarding their historical and religious significance.

In some cases, mosques—whether ASI-protected or not—are threatened by government infrastructure projects, leading to legal battles and protests.

For example, Noori Jama Masjid in Fatehpur faced opposition to partial demolition for road widening. Similar concerns have been raised regarding the mosque in front of Muzaffarnagar railway station and Teeley Wali Masjid in Lucknow, both of which have been subject to legal challenges over demolition risks or restricted access.

These conflicts, documented in court proceedings and government records, illustrate the complex intersection of heritage conservation, legal frameworks, and historical claims in the governance of ASI-protected mosques.

Rehman, Assistant Secretary at Jamaat-e-Islami Hind, said that not all mosques’ committees in these towns are equipped resource-wise to handle systematic targeting by state authorities.

“Earlier, there were not enough resources when mosques were being constructed. No cement was used, whatever material was available was used. Now those structures are being targeted by the authorities on these marks,” Rehman said.

The Indian government has meanwhile amended a decades-old law that governs properties worth millions of dollars donated by Indian Muslims.

The decision triggered protests all over the country. The properties, which include mosques, madrassas, shelter homes, and thousands of acres of land, are called waqf and are managed by a board.

The new amendment law, which introduces more than 40 amendments to the existing law, was enacted in April this year to enhance transparency. But critics say it could weaken protections for waqf properties and heighten disputes over the ownership and classification of religious land.

Meanwhile, Professor Rezavi said the question is not of dispute but of the manner in which the minorities are targeted. “The end result of all this is that the society is getting divided,” he added.

The Polis Project reached out to members of the VHP and RSS who did not comment on the queries about these issues. One of the senior members of VHP, however, said that teams have been set up to look into disputed mosques.

Behind the clamour against so many mosques is not simply disputes over land or legality, but an emerging attempt to erase any Muslim imprint on India’s public life. Religious groups need physical spaces to anchor their collective memory and identity, argued Maurice Halbwachs in his 1980 book ‘The Collective Memory’. This framing could help us understand the present context in India. Each mosque serves as a spatial anchor that stabilises religious identity across generations, enabling believers to recover shared “mental states” and communal experiences when gathering within the walls of the sacred site.

The deliberate erasure of such sacred spaces—where prayers have been recited, celebrations observed, and traditions passed down—threatens to fragment the community’s “religious collective memory”, as per Halbwachs’s argument. Without the spatial manifestations of their faith and tradition, the minority Muslim community loses crucial sites where their religious memory is cultivated and preserved, potentially accelerating cultural erasure and complicating the transmission of religious practices to future generations.

The systematic targeting of mosques and mazars is about memory itself. By fragmenting the spaces where collective memory is nurtured, the Hindutva project accelerates the cultural erasure of Indian Muslims, in an effort to rewrite the nation’s past to secure its majoritarian future.

Related Posts

Patterns of Erasure: How India’s Mosques and Islamic Shrines are Systematically Targeted

In the heart of India’s national capital, Delhi, a few men gather at a tea stall and debate petitions filed against mosques. One insists it’s time “the old glory of Hinduism is returned.” Another recalls that the Mughal rulers “destroyed so many monuments.” These everyday conversations echo a larger project: a campaign to erase India’s Islamic sites under the Bharatiya Janata Party’s rule.

In recent years, mosques, madrassas, tombs, and mazars—shrines built over the graves of revered Muslim saints—have been razed, fenced off, or dragged to court. The right-wing Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), in power of the federal government and in several states, has been on an increasing demolition spree. With the use of the bulldozer, which has become a ‘symbol’ of anti-minority rhetoric, there is a growing trend to bring down Islamic religious structures in an ongoing attack on the Indian Muslim community.

In August 2025, a Hindutva (right-wing, Hindu supremacist) group with raised saffron flags broke through the police barricades in Uttar Pradesh’s Fatehpur to enter a mausoleum (maqbara), claiming it to be a 200-year-old Hindu Thakur temple.

It brings up flashbacks of the Babri Mosque demolitions of 1992, which propelled the BJP to political prominence. In Fatehpur, the mob was seen holding saffron flags and running through the streets. Despite a heavy presence of the Provincial Armed Constabulary and the police, people were able to cross the police blockade and reach the mausoleum. They were seen climbing up the structure and destroying parts of the tomb while shouting slogans of ‘Jai Shree Ram’ (glory to Lord Ram).

The targeting of Muslim heritage sites is not merely about contested land or architectural relics; it reflects a broader attempt to rewrite India’s pluralistic history, delegitimise Muslim presence, and homogenize the cultural landscape in accordance with a Hindu majoritarian narrative.

The deliberate demolition or contestation of these Islamic structures by invoking legal mechanisms, public mobilisation, or state machinery is often done under the garb of reclaiming ‘Hindu heritage’. This form of erasure disrupts not only physical sites but also the memory and effective histories tied to them; it hollows out the pluralism that such spaces historically nurtured.

French political scientist and historian Christophe Jaffrelot, in his book Modi’s India, examines the broader project of India’s Hinduization, transforming a secular nation-state into a champion of the “ethnic nationalism” of far-right Hindus. Jaffrelot frames Hindu nationalism as a system where the dominant group—Hindus—defines the nation through cultural and religious identity, which fosters a sense of superiority and excludes Muslims. This model thrives on a perceived threat from minorities, and that in turn, is used to justify majoritarian mobilization.

In India, Muslims are increasingly portrayed as internal enemies, leading to their marginalization and persecution. While noting the incongruence of democracy with such “ethnic nationalism”, Jaffrelot writes: “…Modi’s India, during NDA II, can be said to have invented a de facto ethnic democracy, a political system in which the state remained relatively in the background, leaving the field open to vigilante groups, which, with the tacit or explicit support of law enforcement bodies, went after “deviants,” whether they were champions of secularism or members of minorities.”

Whether it’s the official turn towards calling India “Bharat”, or the prime minister’s fear-mongering about Muslims during election campaigns, or the many organs of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) rallying against mosques and other religious structures, the said Hindu nationalist or Hindutva project is in motion. Against this backdrop, the multi-pronged efforts to remove Islamic sites appear as part of a sustained project of cultural majoritarianism.

Attack on Religious Institutes

Since 2014, when the BJP government came to power, India’s 200 million minority Muslims have been subjected to persecution, violence, and discrimination. Under the banner of Hindutva (Hindu nationalist), which aims to establish India as a Hindu nation, rather than a secular state, Muslim civilians, activists, and journalists have been routinely targeted. There has also been a move to boycott Muslim-owned businesses, target Muslim places of worship, and use Islamophobic rhetoric by BJP leaders, while the lynching of Muslims has been on the rise.

Amid this climate, mosques and mazars have increasingly been marked for legal challenges or demolition. In early October this year, the Supreme Court of India upheld the partial demolition of a 400-year-old mosque complex in Ahmedabad, Gujarat. The ruling allowed for the clearing of an adjoining platform and the obtaining of land for a road-widening project, while the main structure would remain intact.

Authorities in several states have also cited “encroachment” laws to justify mosque and mazaar demolitions, yet similar scrutiny has not been applied to other structures in the same areas. This selective enforcement has fueled concerns that these efforts are part of a broader ideological push to redefine India’s historical and religious landscape through the lens of Hindutva.

The Polis Project investigated the legal petitions filed against the mosques, the demolitions of mosques and mazars, the individuals and groups behind these efforts, and the patterns of violence and disputes that have arisen in the name of historical reclamation.

The Babri Blueprint to Recast India’s Religious Landscape

The pattern of demanding erasure of mosques based on contested history can be traced back to the Ram Janambhoomi movement, led by veteran BJP leader LK Advani. It was a political rally travelling across much of northern India to Ayodhya, a town in Uttar Pradesh.

The campaign sought to generate support for a proposed Ram Temple at the site of the Babri Mosque. It ended in the demolition of the 16th-century mosque by a Hindu mob in 1992. It gave rise to communal violence across India and eventually propelled a wave of popularity for the BJP, bringing it to power in 1998. The mosque had been constructed by the Mughal Emperor Babur. The dispute centered on the claim that a Hindu temple lay underneath it, and it was believed to be the birthplace of Rama, a Hindu mythological figure and deity.

The trend has traversed decades to survive and flourish under the Narendra Modi-led government. In 2025 alone, several incidents of mosque and mazaar demolitions have been reported.

In March this year, Mughal emperor Aurangzeb’s tomb in Maharashtra’s Chhatrapati Sambhajinagar had to be put under heavy security after Hindu outfits like Vishwa Hindu Parishad and Bajrang Dal threatened a “Babri Masjid-like fate” if their demand to remove the structure was not met by the state government. VHP and Bajrang Dal members also staged a protest in front of the Nagpur District Collector’s office over their demand to remove Aurangzeb’s tomb. Hours after, clashes erupted amid rumours that a cloth bearing the Islamic declaration of faith, or Kalma, had been burned during the protest, prompting stone-pelting at the police. This eventually led to the arrest of around 100 people, including several Muslims.

The spate of mosque and mazar demolitions across India in early 2025 — from Bet Dwarka and Ujjain to Bahraich and Dibrugarh — reflects a distinct pattern of religious structures being targeted by encroachment drives. There is no concrete data available for incidents of mosque demolition or attempts at the same. To present a rough idea of the scale, The Polis Project recorded 15 cases from media reports in the first six months of 2025.

Certain areas in the country have turned into hotbeds of tension between Hindu and Muslim communities over mosque disputes. Sambhal, a historically significant district in the northern state of Uttar Pradesh, has remained on edge for over a year. In October this year, a mosque in the village of Raya Buzurg in Sambhal was demolished after the Allahabad High Court dismissed a petition seeking a stay. Authorities said it stood illegally on reserved pond land.

It is noteworthy that the Uttar Pradesh government is led by firebrand BJP leader and Hindu nationalist Yogi Adityanath, who is known for using the bulldozer against the Muslim community in incidents of punitive demolitions, which have been extensively reported by The Polis Project.

In 2024, a dispute erupted over the 16th-century Mughal-era Shahi Jama Masjid in Sambhal after Hindu groups claimed the mosque stood on the remains of an ancient temple.

On 24 November 2024, a team from the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI), the state agency for conservation of cultural and historical monuments, arrived to survey the Shahi Jama Masjid, accompanied by a group of Hindu right-wingers.

The survey was done in the wake of a petition filed by advocate Hari Shankar Jain, who challenged the mosque committee’s claim that it was responsible for the mosque’s maintenance under a 1927 agreement, arguing that the responsibility lay with the ASI.

While delivering its order, Jain requested the bench to refer to the mosque as a “disputed structure,” and the court agreed.

On the day of the survey, violence erupted when rumours spread that ASI officials were demolishing an old well inside the mosque, and this made many of the locals angry. In retaliation, police fired shots at unarmed protesters, killing six.

One of those killed was Naeem, a 35-year-old resident of Sambhal and a tailor by profession. He was killed by a bullet that hit his chest.

Months later, Idreesa, his mother, continued to reel from the sudden loss of her son. She sat in her small house near the Shahi Jama Masjid, speaking to these reporters. In moments between the conversation, she clutched her chest as if in pain, with tears pooling in her eyes. “My son is gone, my son is gone,” she said.

According to historians and locals alike, Sambhal has always been a place of conflict. During the conversations with locals from both the Hindu and the Muslim communities, different versions of history can be heard.

Among the Muslim locals, a gruesome story travels: On one fateful night during Shivratri, a Hindu festival dedicated to Lord Shiva, a Hindu mob entered the Jama Masjid in Sambhal, tied the Maulana, and slit his throat during the 1976 communal violence.

“His blood was splashed all over the mosque,” Areeba, a local woman who lives near the mosque, said, recalling the event.

After the violence and a month-long curfew, Sambhal became a communally sensitive hotspot. Another riot broke out in 1978, wherein the Parliament considered sending a team to the tiny town on a fact-finding mission.

But what made the Shahi Jama mosque a place of conflict? Hindus believe that Sambhal is the place where the Hindu god Kalki would be born. The ‘satya yug’ or the golden age, according to Hinduism, is supposed to start in Sambhal with Kalki’s birth. “We are proud to be born at a place where Lord Kalki’s birth will take place,” Rajesh Kumar, a resident of Sambhal, said.

With such stories and incidents shaping both the communities, the tensions, which Sambhal has witnessed in 1976, 1978, and 1992 ( right after the demolition of Babri Masjid), have resurfaced. But locals said, barring these years, the small town has usually been quiet, until 2024.

The claim of dispute around Shahi Jama Masjid was also based on a court case that claimed the mosque was built on the site of Harihar Mandir, where Kalki is supposed to be born.

How Mosques Became Political Targets

Most of the mosques, against which petitions are filed, were built during the Mughal era. This, however, cannot be said about mazars and other Islamic structures.

Several experts believe the Mughal structures are targeted deliberately, as it helps create a historical “other” against the Hindu “self”.

Ghazala Jamil, Assistant Professor at the Centre for the Study of Law and Governance in Delhi’s Jawaharlal Nehru University, said the focus on the Mughals by Hindutva groups is not random and can be explained through several “overlapping reasons”.

“The Mughal Empire has a quick recall value and is more visible in India’s public culture than earlier Muslim dynasties because of its lasting monuments, like the Taj Mahal which has come to represent India itself in the world’s imagination, or the Red Fort which became a symbol of India’s sovereignty,” she explained.

According to Jamil, another reason is that Mughal rule was relatively stable over a long period. Mughals remained in power, even if only notionally, right up to the mid-19th century, which makes it easier for people to recall and imagine it compared to older, less unified kingdoms. “At the same time, British colonial historians had already framed a part of Indian history as a story of Hindu decline under Muslim rulers, which Hindutva groups find simple and handy for their own purposes. This ready-made story paints the Mughals as foreign occupiers, making them a convenient target for a politics that seeks to reclaim an imagined pure Hindu past,” she added.

Losing a Past of Religious Harmony

Unlike mosques, places like mazars have long played a significant role in cultural integration and harmony.

Rana Safvi, an Indian historian and writer who has worked on the documentation of mosques and mazars of India, told The Polis Project that historically, both mosques and mazars have played significant roles as a cultural and spiritual space for not just Muslims but also other communities.

“In both Delhi and Uttar Pradesh, between 1947 and 1957, there was an influx of partition refugees. And it is at mazars and tombs that these refugees stayed. They were desperate for a place to live in and many of them stayed wherever they could, so these monuments became a place of refuge. I call this a tragedy, because this led to the erasure of many such places,” she said.

In all of this, one cannot rule out the role of the Mughals in constructing these magnificent monuments and marking parts of India’s history in stone, many of which are now being targeted for that very same reason.

In her blog post, Safvi says Delhi became the hotspot for Mughals to construct various monuments after they declared their capital. Delhi, which was once known as Shahjahanabad—after Mughal Emperor Shah Jahan who built it in 1639—and home to several fifth and sixth generation residents, all of whom Safvi describes as “keepers of its history.”

The city today, she says, is far removed from the vision of its chief architect. “Shah Jahan was a prolific builder. When he gave orders to build a new city, he envisaged a magnificent place on the theme of paradise, built on the banks of the River Yamuna. It was also a planned city with specific areas allocated according to trade, profession and hierarchy. Land was allotted for havelis, gardens, bazaars and religious buildings. This city bore the brunt of the revolt of 1857 when the British looted the nobility, banished residents and rearranged the city for administrative purposes,” she said.

A Long Thread of Demolition Politics

Despite its importance, the Babri Mosque was not the start of the “demolition politics” as we have come to know today. In the book, Hindu Temples: What Happened to Them, written by Sita Ram Goel, Arun Shourie, Harsh Narain, Jay Dubashi, and Ram Swarup, there exists a list of such structures and monuments in India that several groups want demolished. The book mentions a list prepared by the Hindu Mahasabha that has been in circulation for long and, at the time of the book’s publication in 1990, the tally stood at 880.

These 880 monuments, established by Muslims, are not just mosques but include idgahs, imambaras, baradaris, cemeteries, and graves of Sufi saints. The largest chunk of these, roughly 281, are graves and mazars of Sufi saints and common Muslim cemeteries. However, in India, they are a place of cultural integration, with people from different religious backgrounds coming together to witness traditions that were once celebrated and pray for things.

In her book The Sufi Courtyard: Dargahs of Delhi, Sadia Dehlvi narrated how these places, often described as the “origins of Sufism” have a cultural significance. “This city (Delhi)”, she says, “has always been an important centre of the different Sufi orders called silsila. Delhi’s inclusive culture ensures that though Chishtis are the dominant order here, other orders such as Suharwardis, Qadris and Naqshbandis continue to have a presence.”

Media reports and research show the number of mazars being attacked has increased significantly, wherein self-styled Hindutva activists have taken it upon themselves to take the law into their own hands and demolish mazars. Many mazars have been demolished in Himachal Pradesh in the past year. Such structures are also destroyed under “encroachment” allegations. However, it is extremely difficult to find conclusive data on this.

In his article, Babri Masjid and the politics of demolition, activist and scholar Ali Fraz Rezvi writes, “There have been several instances when mazars and graves were either attacked by a mob or demolished on the orders of the government. They include the demolition of seven mazars in UP’s Mathura in 2018, ordered by the Adityanath government, the one in Barabanki in 2021, and the mazar between Chaubepur and Shivajipur, Kanpur, in 2022, by government authorities, and the vandalisation of the mazars of Jalal Shah, Bhureshah, and Qutubshah in Bijnor.” Rezvi goes on to add that “Similar cases were reported in Gujarat and Uttarakhand as well. The year 2022 alone has reportedly witnessed the demolition of more than 12 mazars.”

In November 2022, Home Minister Amit Shah stated that “fake mazars” have been cleared from Gujarat as part of the BJP-led State government’s “clean-up” policy. He has also, on various occasions, emphasized that mazars and graves were illegal encroachments and thus would be removed.

Amid this, what is lost are places of mystic traditions and cultural gatherings. In Delhi, for example, the Mandi House mazar, which was demolished by civic authorities in April 2023, was where the national capital’s theatre scene buzzed. Hundreds of star-glazed theatre artists sat by the mazar drinking tea and talking about art, films, and politics. But now, instead of the mazar, there is a piece of modern architecture with shiny lights blending the space into generic urban scenery.

The dargah, which was demolished, was known popularly as the Nanhe Mian Chishti Dargah and is known to be two centuries old. For as long as anyone who has lived in Delhi can remember, the dargah has been a part of their existence.

This is not the only case. A demolition drive between 2023 and 2024 in Delhi razed more than 15 dargahs. As per media reports, in the same period, the Uttarakhand government bulldozed more than 300 mazars in the state. Vigilantes associated with Hindutva groups, like Dev Bhoomi Raksha Ahbyan, continue vandalising and destroying Muslim religious sites in the state.

Many dargahs have been demolished in Uttar Pradesh as well. Safvi calls it an “erasure of history”.

An Aligarh Muslim University scholar, Zainab, who has studied the history and art of Islamic structures, said that despite their research on mazars, these remain ignored structures and their obliteration often fail to attract much attention. “I myself have come across so many news reports of a dargah getting demolished but did not pay any attention. In Aligarh itself, mazars have been demolished,” she said.

Other Historical Disputes

In June 2021, Pandit Keshav Dev Gautam, a self-styled ‘anti-corruption activist’ and national Chief of Bhrashtachar Virodhi Sena (BVS), filed a petition with the Municipal Corporation of Aligarh under the Right to Information Act, demanding information about the Jama Masjid of Aligarh.

He claimed that the response revealed the mosque was constructed on “Public Land,” though the Aligarh Municipal Corporation had already dismissed those claims. Following the response from the municipal corporation, he also wrote to the district magistrate demanding demolition of the mosque.

The Polis Project met with Gautam in his small office attached to his house in Aligarh. Wearing a checked shirt and wrapping a green cloth on his head, Gautam introduced himself as a ‘pandit’ and an ‘activist’.

Gautam is not originally from Aligarh; he is not even from Uttar Pradesh, but a resident of Haryana who migrated here two decades back.

He started filing Right to Information (RTIs) that led him to believe that one of India’s oldest mosques was constructed on the periphery of a Shiv Temple. While hinged on fighting corruption, Gautam’s ideology resembles what is propagated by religious right-wing organisations. However, he is not a part of the VHP or Bajrang Dal, who are, most of the time, behind such claims of dispute.

“I have no issues with them [Muslims], but we cannot deny the Mughals made an empire by destroying Hindu structures. I just want accountability,” he said.

Further, in January 2025, Gautam filed another petition in the Aligarh district court, alleging the Jama Masjid was illegally built over a Shiva temple. He cited Jahangirnama (1610-17) to claim that Sidha Khan, a Mughal-era ruler of Aligarh, built the Jama Masjid on public land.

However, experts said that Sidha Khan governed during Mughal ruler Aurangzeb’s reign (1658-1707), making such a reference in the Jahangirnama historically dubious. When asked, Gautam revised his claims, revealing inconsistencies.

“There was no [Jama] Masjid in 1753 during Raja Surajmal’s time,” he asserted. However, historical records show that construction began in 1724 under Sabit Khan, Governor of Kol, during Muhammad Shah’s reign (1719-1728), and was completed in 1728. Sabit Khan’s grave still lies 700 meters from the mosque.

In 1740, Reja Muhammad’s Persian account, Akhbar-ul-Jamal, documented that the Jama Masjid, built by Sabit Khan, spanned 4,004 square yards at that time.

Gautam also claimed this was not a “Hindu-Muslim” issue, but that “those people” have encroached on the shops outside the masjid.

However, experts told The Polis Project that this information is distorted. Senior Professor of History at Aligarh Muslim University, Syed Ali Nadeem Rezavi, who also serves as the secretary of the Indian History Congress, said, “The mosque does not belong to Jahangir’s period at all. There may have been several mosques, including structures in the old city of Kol and the Upperkot area, which date back to the early Sultanate period.” Additionally, there is a tomb from Mughal ruler Babur’s era, along with structures built under Muslim rulers like Khilji and Tughlaq.

Rezavi explained that Aligarh, in ancient times, was known as Kol, named after a demon who was killed by the brother of Lord Krishna, Balarama, according to Hindu legends.

“Let us not delve into history. The Supreme Court upheld the Places of Worship Act of 1991. However, the issue lies with lower courts admitting petitions that undermine this ruling to bully the minorities of the country,” Professor Rezavi said.

On the other hand, Gautam claimed that the issues he raised were supported by the Rashtrawadi (nationalist) and Dharmaic (religious) factions. “The court has not prohibited us from filing petitions. It is not a Mandir-Masjid dispute. It is about how Muslims have illegally occupied the structure,” he said.

Aligarh’s Jama Masjid is no ordinary mosque. It is one of the oldest surviving Mughal mosques in the country. It was declared a protected monument in 1920 and has remained so since.

Gautam is demanding that the “encroachers” be thrown out immediately and that all illegal construction be demolished. He alleged that the shops are benefiting the masjid committee, which in reality, is an unofficial organisation started by people from within the community.

The Polis Project reached out to the masjid committee, who refused to comment on the court matter and said they are “taking legal help”. They further claimed that the self-acclaimed activist is trying to stir communal tensions that “do not exist”.

Although the Supreme Court has put a stay on the petition, it has opened the mosque to scrutiny with the right-wing groups, forming committees to look into the matter and reach out to the court again.

Legal Loopholes

In 2022, during the hearing of the Gyanvapi Mosque petition, former Chief Justice of India DY Chandrachud, made an oral observation stating that Sections 3 and 4 of the Places of Worship Act, 1991, do not prohibit the “ascertainment of religious character” of any place of worship.

This observation had serious repercussions at the lower judiciary with a number of districts and sessions courts, especially in Uttar Pradesh and Rajasthan, admitting petitions seeking to “ascertain the religious character” of mosques and other places of worship built in medieval India and ordering their surveys.

Among the places facing calls for survey are the Ajmer Dargah, Adhai Din ka Jhonpra, the Shahi Jama Masjid in Sambhal, the Teelewali Masjid in Lucknow, the Shamsi Jama Masjid in Badaun, the Atala Masjid in Jaunpur, including the famous cases of Gyanvapi Masjid, the Eidgah in Mathura and Kamal Maula Masjid in Dhar.

The Places of Worship (Special Provisions) Act, 1991, freezes the religious character of all places of worship as it existed on August 15, 1947. This Act prohibits any conversion of a place of worship to a different religious denomination or even within the same denomination. It also prevents courts from entertaining any disputes regarding the religious character of places of worship as it existed on August 15, 1947. However, the Ayodhya site is an exception in this matter.

According to official documents accessed by The Polis Project, there are, as of now, 58 mosques that are under dispute.

Speaking to The Polis Project, Supreme Court Advocate Ali Zaidi said that the loophole left by former Chief Justice DY Chandrachud is being used by these groups to file civil suits and make these sites disputed property.

“They say that it is not a mosque at all. Even if you read the High Court judgement of this Shahid Jahan Masjid in Ayodhya. You are now using a different strategy altogether to circumvent it and courts are accepting it,” Zaidi said.

Instead of shutting down the controversy altogether, the former CJI left this caveat in his Babri judgement, which has led to multiple civil suits, including that of Sambhal, claiming these Islamic places are not religious sites.

What Gautam did was file a petition on the information he got through Right to Information (RTI). This is part of a pattern of filing RTIs and trying to relate the information to distorted historical facts.

“To prove a site is disputed you have to prove a prima facie to show the same. For that you have to have some material. For that purpose, I file an RTI and ask a vague question, which will suit my intent,” Zaidi explained.

According to an affidavit submitted to the Supreme Court in a plea to uphold the constitutional validity of the Places of Worship (Special Provisions) Act of 1991, 11 mosques in India are facing a total of 18 lawsuits from Hindu outfits, which claim them to be temples.

On 12 December 2024, the Supreme Court of India directed trial courts across the country not to pass any effective orders or surveys against existing religious structures in suits filed disputing the religious character of such structures until the apex court decides on the constitutional validity of the Places of Worship (Special Provisions) Act.

The Bench also directed that “in pending suits, the courts would not pass any effective interim orders or final orders including orders of survey till the next date of hearing”.

In the disputed cases, seven out of the 11 mosques are in Uttar Pradesh, with one each in Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan, Karnataka, and New Delhi.

Disputed, Contested, and Erased

An analysis of 25 targeted mosques across the country shows that 13 are clearly ASI-protected, one is a historically significant but non-protected structure, and another falls under enemy property regulations.

Additionally, according to a Waqf volunteer who requested anonymity, 38 mosques and religious structures in Delhi alone have been targeted in legal or administrative proceedings.

In conflicts involving ASI-protected mosques, many of the disputes center around restrictions on worship and access. For instance, at the Quwwat-ul-Islam Mosque in Delhi, worship is not permitted due to the ASI’s conservation rules. Legal battles frequently arise over ownership and status, with petitions seeking to determine whether these mosques should be treated as religious sites or historical structures.

In several cases, ASI surveys have been demanded to examine the origins of these mosques, especially where claims exist that they were built over pre-existing Hindu temples.

The Gyanvapi Mosque in Varanasi, Uttar Pradesh, is another example that has been the subject of legal disputes, with petitions calling for an ASI survey to investigate its origins. Similarly, in Mathura, Hindu groups have pushed for an ASI survey of the Shahi Idgah Mosque, citing its proximity to the Krishna Janmabhoomi temple.

Immamur Rehman, Assistant Secretary at the Jamaat-e-Islami Hind Headquarters, said mosque committees are facing difficulties despite having proper documents. He added that in the case of Gyanvapi, the mosque committee had “sufficient records and literature of those times which they submitted all in the court.”

“Going to Gyanvapi is not very easy now. It is surrounded on all sides with barricades and checkpoints for prayers, no phones, no electronics and all around it there is a temple where there is free access, people are coming and going, all the roads that lead to the mosque are also theirs, such an atmosphere has been created that if one gate of the mosque is closed, going to the mosque will be stopped,” Rehman observed.

These disputes often become politically and communally sensitive, with right-wing groups advocating for the “liberation” of certain mosques. This has led to court cases, religious mobilization, and heightened tensions. ASI and local authorities sometimes undertake restoration work that alters structures or results in restricted access, further complicating these disputes.

Atala Masjid in Jaunpur, Kamal Maula Masjid in Dhar, and Adhai Din Ka Jhopra in Ajmer have all been at the center of debates regarding their historical and religious significance.

In some cases, mosques—whether ASI-protected or not—are threatened by government infrastructure projects, leading to legal battles and protests.

For example, Noori Jama Masjid in Fatehpur faced opposition to partial demolition for road widening. Similar concerns have been raised regarding the mosque in front of Muzaffarnagar railway station and Teeley Wali Masjid in Lucknow, both of which have been subject to legal challenges over demolition risks or restricted access.

These conflicts, documented in court proceedings and government records, illustrate the complex intersection of heritage conservation, legal frameworks, and historical claims in the governance of ASI-protected mosques.

Rehman, Assistant Secretary at Jamaat-e-Islami Hind, said that not all mosques’ committees in these towns are equipped resource-wise to handle systematic targeting by state authorities.

“Earlier, there were not enough resources when mosques were being constructed. No cement was used, whatever material was available was used. Now those structures are being targeted by the authorities on these marks,” Rehman said.

The Indian government has meanwhile amended a decades-old law that governs properties worth millions of dollars donated by Indian Muslims.

The decision triggered protests all over the country. The properties, which include mosques, madrassas, shelter homes, and thousands of acres of land, are called waqf and are managed by a board.

The new amendment law, which introduces more than 40 amendments to the existing law, was enacted in April this year to enhance transparency. But critics say it could weaken protections for waqf properties and heighten disputes over the ownership and classification of religious land.

Meanwhile, Professor Rezavi said the question is not of dispute but of the manner in which the minorities are targeted. “The end result of all this is that the society is getting divided,” he added.

The Polis Project reached out to members of the VHP and RSS who did not comment on the queries about these issues. One of the senior members of VHP, however, said that teams have been set up to look into disputed mosques.

Behind the clamour against so many mosques is not simply disputes over land or legality, but an emerging attempt to erase any Muslim imprint on India’s public life. Religious groups need physical spaces to anchor their collective memory and identity, argued Maurice Halbwachs in his 1980 book ‘The Collective Memory’. This framing could help us understand the present context in India. Each mosque serves as a spatial anchor that stabilises religious identity across generations, enabling believers to recover shared “mental states” and communal experiences when gathering within the walls of the sacred site.

The deliberate erasure of such sacred spaces—where prayers have been recited, celebrations observed, and traditions passed down—threatens to fragment the community’s “religious collective memory”, as per Halbwachs’s argument. Without the spatial manifestations of their faith and tradition, the minority Muslim community loses crucial sites where their religious memory is cultivated and preserved, potentially accelerating cultural erasure and complicating the transmission of religious practices to future generations.

The systematic targeting of mosques and mazars is about memory itself. By fragmenting the spaces where collective memory is nurtured, the Hindutva project accelerates the cultural erasure of Indian Muslims, in an effort to rewrite the nation’s past to secure its majoritarian future.

SUPPORT US

We like bringing the stories that don’t get told to you. For that, we need your support. However small, we would appreciate it.