“At no time have governments been moralists. They never imprisoned people and executed them for having done something. They imprisoned and executed them to keep them from doing something. They imprisoned all those prisoners of war, of course, not for treason to the motherland…They imprisoned all of them to keep them from telling their fellow villagers about Europe. What the eye doesn’t see, the heart doesn’t grieve for.”

― Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, The Gulag Archipelago, 1918-1956

‘Political Prisoner’ is a category of criminal offense that sits most egregiously in any civilized society, especially in countries that call themselves liberal democracies. It is a thought crime: the crime of thinking, acting, speaking, probing, reporting, questioning, demanding rights, and, more importantly, exercising one’s citizenship. But these inhumane incarcerations do not just target private acts of courage, they are bound together with the fundamental questions of citizenship, and with people’s capacity to hold the State accountable. Especially States that are unilaterally and fundamentally remaking their relationship with their people. The assault on the fundamental rights has been consistent and ongoing at a global level and rights-bearing citizens are transformed into consuming subjects of a surveillance State.

In this transforming landscape, dissent is sedition, and resistance is treason.

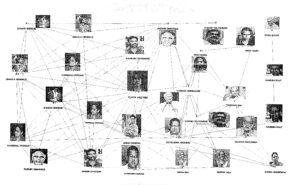

While the Indian State has a long history of ruthlessly crushing dissent, a new wave of arrests began in 2018. Eleven prominent writers, poets, activists, and human rights defenders have been in prison, held under the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act. They are accused of being members of a banned Maoist organization, plotting to kill Prime Minister Narendra Modi, and inciting violent protests in Bhima Koregaon. To date, no credible evidence has been produced by the investigating agency, and those accused remain incarcerated without bail. Since the anti-Citizenship Amendment Act protest began in December 2019, students, activists, and peaceful protesters have been charged with sedition, targeted with violence, and subjected to arrests. Since then, more arrests have followed specifically targeting local Muslim students leader and protestors, including twenty-seven-year-old student leader Safoora Zargar.

Since the COVID-19 lockdown was announced, India’s leading public intellectuals, opposition leaders, writers, thinkers, activists, and scholars have written various appeals to the Narendra Modi government for the release of India’s political prisoners. They are vulnerable to COVID-19 contagion in the country’s overcrowded jails, where three coronavirus-related deaths have already been reported. In response, the State has doubled down and rejected all the bail applications. It also shifted the seventy-year-old journalist Gautham Navlakha from Delhi’s Tihar Jail to Taloja, without any notice or due process – Taloja is one of the prisons where a convict has already died of COVID-19.

A fearful, weak State silences the voice of dissent. Once it has established repression as a response to critique, it has only one way to go: become a regime of authoritarian terror, where it is the source of dread and fear to its citizens.

How do we live, survive, and respond to this moment?

In collaboration with maraa, The Polis Project is launching Profiles of Dissent. This new series centers on remarkable voices of dissent and courage, and their personal and political histories, as a way to reclaim our public spaces.

Profiles of Dissent is a way to question and critique the State that has used legal means to crush dissent illegally. It also intends to ground the idea that, despite the repression, voices of resistance continue to emerge every day.

This profile has been compiled by Tazeen Junaid. You can read Varavara Rao’s profile here, the profile of Sudha Bharadwaj here, that of GN Saibaba here, Gautham Navlakha’s profile here, Anand Teltumbde here, Sharjeel Usmani here, Shoma Sen here, Surendra Gadling here, Asif Iqbal Tanha here, Rona Wilson here, Sudhir Dhawale here, Sharjeel Imam here, Arun Ferreira here, Umar Khalid here, Father Stan Swami here, K. Satyanarayana here and Mahesh Raut here.

HANY BABU

Hany Babu Musaliyarveettil Tharayil, 54, is an associate professor of Linguistics in Delhi University (DU). He is also a linguist, an anti-caste scholar, and a social activist. His work as an activist has been largely related to the pro-reservation movement in Indian universities. He is the coordinator of the Alliance of Social Justice, a member of the Joint Action Front for Democratic Education and, until his arrest, he was leading the Defense Committee for GN Saibaba, a professor convicted for alleged links with the Maoist movement.

Babu grew up in the Malabar area of Kerala as a Moplah Muslim belonging to Other Backward Class (OBC – this refers to social groups that are marginalized by systematic oppression and entitled to affirmative action from Indian state). He studied at the Hyderabad campus of English and Foreign Languages University (EFLU) where his journey as a successful Dalit-Bahujan (an umbrella term for marginalized groups in India) academic began: he belongs to the first generation of students who accessed higher education after the Mandal Commission (1990) recommended affirmative action for OBCs in Indian universities. Internationally renowned for his work on linguistics and the recipient of the Best Young Linguist award, Babu worked in several German universities from 1997 to 2001. He then joined the Hyderabad campus of EFLU as an Assistant Professor of Linguistics in 2002 and became one of the first OBC candidates to be employed there after the implementation of Mandal Commission.

Hany Babu moved to Delhi in 2008 when he was appointed as a professor in DU where, as an activist, he worked towards securing academic rights of OBC students through the proper implementation of reservation policies. His work as a professor, his pedagogical practice and his activism were heavily influenced by the Ambedkarite idea of total revolution. As the secretary of Academic Forum for Social Justice, a forum for OBC teachers, he collected data from 30 colleges of DU and exposed the huge gap that exists between the seats allocated for OBC students and those filled. He also protested for the proper implementation of reservation for OBC students in DU, undertook successful litigation against the discriminatory practices in the admission process for OBC students and tried to make the syllabus more inclusive for Dalit-Bahujans. He also drafted the rules for the election to the student-faculty body of DU to ensure representation from all sections of society.

Babu is a strong proponent of using English as a tool to liberate Dalit-Bahujans. His work, as an anti-caste scholar, focuses on the ideology of language, linguistic identity, marginalized languages and social justice. His writings on caste and Indian languages concentrate on the problems of Indian language policies.

Babu’s house was raided early morning on 10 September 2019 for his alleged connections in the Bhima Koregaon-Elgaar Parishad case even though he was not present in Koregaon when the incident took place. The raid was carried out without a search warrant, in violation of both due procedure and Babu’s civil rights. The raid went on for six hours during which Babu, his wife and daughter were physically held, and their phones confiscated. Babu was forced to give permanent access of his email account and social media handles. He was questioned about his participation in the Defense Committee for GN Saibaba and anti-caste movements as well as about his relations with Rona Wilson and Surendra Gadling, two other accused in the Bhima Koregaon-Elgaar Parishad case. His laptop, mobile phones, hard disks, pen drives, two booklets printed for the GN Saibaba Defence Committee and two books were seized. The seized books were From Varna to Jati: Political Economy of Caste in Indian Social Formation by Yalavarthi Naveen Babu and Understanding Maoists: Notes of a Participant Observer from Andhra Pradesh by N. Venugopal. Babu feared that these books would be used to depict him as an academic sympathetic to Maoist and left ideology. He also suspected that some incriminating evidence might be implanted on his devices as their hash value was not provided to him (hash value is a numeric value which identifies and reflects any change that occurred to the data on the devices).

In an interview with the Caravan Magazine, Babu criticized the raid: “If you seize my laptop and mobile phone, I would say it is more of an intimidation. It is precisely because they know how you can cripple an academic, because the hardship I’m going through now for the last two–three months, without access to teaching or research material, this is actually worse than incarceration. If they had locked me up for a week, two weeks, a month, they could do this search while I am inside. That would have been much better. It’s very clear that they are hunting academics, so there is clearly a project to intimidate and silence people.”

Babu was summoned to appear on 15 July 2020 in Mumbai as a witness in the Bhima Koregaon-Elgaar Parishad case on the basis of the data extracted from his seized devices, email and social media handles. Babu requested to appear via video conferencing as travelling during COVID-19 pandemic was a health hazard, but this appeal was denied. Despite maintaining that he had no connection in the Bhima Koregaon-Elgaar Parishad case, Babu travelled to Mumbai on 24 July to appear in front of National Investigation Agency (NIA) in the spirit of cooperation. He was questioned about his relationship with the other accused in the case and about a “hidden folder” found in his laptop, which allegedly contained letters written by Maoists. As the questioning progressed, NIA officers began pressurizing him; he was asked to admit to his own complicity in the case by accepting allegations of being a functionary of Maoist groups. Babu vehemently and persistently denied all allegations, however NIA arrested him after five days of interrogation, on 28 July 2020.

Babu was charged with propagating Naxal activities and Maoist ideology as well as for being a co-conspirator in the Bhima Koregaon-Elgaar Parishad case and remains lodged at Taloja Jail in Maharashtra. NIA later informed Babu’s wife that he was arrested as the “hidden folder” on his laptop established him as a Maoist. His house was raided again on 3 August after his arrest to recover further incriminating evidence including pen drives, one hard disk, and documents related to the Defense Committee for GN Saibaba. Civil society groups of Delhi University and the People’s Union for Civil Liberties condemned the raid in press statements on suspicion of it being a disguise to plant evidence implicating Babu as the hash value of the seized electronic items was never provided.

Date of arrest: 28 July 2020

Charges: Babu was arrested for allegedly supporting Naxal activities, propagating Maoism and being a co-conspirator in the Bhima Koregaon-Elgaar Parishad case. The arrest was made under various charges, including violations of Section 153 (provocation with intent to cause riot), Section 505 (intent to cause harm to the public/army) and Section 117 (abetting commission of offence by the public or by more than ten persons) of the Indian Penal Code. He was also charged under relevant non-bailable sections of Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act and has been taken under extended judicial custody.

Update: Hany Babu remains incarcerated in Taloja Jail where prison authorities denied him access to newspapers and books. He went on a symbolic hunger strike in solidarity with farmers’ protest on 23 December 2020 along with Mahesh Raut, Anand Teltumbde and other accused of the Bhima Koregaon-Elgaar Parishad case.

If you are in a university and oppose state policy, you can be targeted: Hany Babu, DU professor – Excerpt from an interview with Shaheen Ahmed and Maya Palit

The kind of work I am doing, obviously it must have a link to that, because they do not randomly pick people. I think the bulk of my work and engagement has been in issues relating to discrimination, social justice, reservation. But that alone, I am sure, would not have attracted this kind of attention or attack from state agencies. So, there is clearly a kind of message being sent out: that you have to be careful about what kind of activities you are engaged in.

Apart from reservation, another angle which I am working on and have been engaged in is things related to education and education-policy changes. When there was an attempt to launch the four-year undergraduate programme in Delhi University, some of us had very actively opposed it. And we were successful in that. So a lot of my friends also feel the same: given that there is an attempt to overhaul the education policy—maybe not obliterate, but the state universities are being sidelined and there is a watering down of education and maybe scuttling of reservation—all these things are going to come. A lot of changes are going to come, so maybe this is also a kind of signal sent to academics now—I am not saying that it’s attacking me alone—if you are in a university and if you oppose state policy in any way, then you can be targeted.

I can see this now when anything is happening, many of my colleagues and friends in the university are actually thinking twice—earlier they would speak freely against state policy, if there is some change, they would openly attack it. Now they think, “After all, we are government employees.” This concept of being government employees was not there for university teachers, whereas now teachers [think], “Can we criticise the government?” There is this attempt to bring in the civil service—CCS—rules, which govern civil servants. Actually, university teachers are not bound by that. It will basically mean that you cannot oppose the state.

If the raid was about the Elgar Parishad or Bhima Koregaon, I am sure the officers who came know pretty well that I was nowhere in the picture when the meeting was conducted, in preparation for the meeting or after the meeting. I have not even participated in any meetings or corresponded with anyone. Nothing. I am sure they know this. The only connection I kind of see, with some of the people who have also been arrested, is because of my activities with the defence committee. That is what they asked me—very meaningfully they asked, “Do you know Surendra Gadling?” Now Surendra Gadling is a person who has been arrested and he is also the lawyer who was in charge of Saibaba’s case in Nagpur. Obviously I know him because we were part of the defence committee. I have talked to him, called him maybe once or twice. I have also met him once or twice, in Nagpur. I said yes. “Do you know Rona Wilson?” Rona, I also know as a friend. I said, “Yeah, I know him. And so?” After that they do not say anything. Knowing them is enough. By knowing them, with your association with them, you become a suspect for us. They also said that they have some material and I kept asking them, “At least tell me what kind of material, how am I linked to this?” They refused, they kept saying, “We have some material, but we will now look at your records and documents and all and see whether it corroborates. If there is corroboration, we may need to arrest you. Right now we are not arresting you, you are only a suspect, you are not an accused.” So it’s more guilt by association.

The position of law is very clear, there is nothing like guilt by association in our jurisprudence, whereas for the investigating agencies, they work with this. Because if they do not want to punish me, they can very well give me a copy at least, or allow me to take a copy of the material. Let them confiscate my laptop, why can’t they make at least a copy of my material available so that I can work?

Tazeen Junaid is an activist based in Aligarh and writes on issues of gender equity, Indian minorities, and the anti-CAA movement. She is currently pursuing her Bachelors in Literature from Aligarh Muslim University.

Related Posts

HANY BABU

Hany Babu Musaliyarveettil Tharayil, 54, is an associate professor of Linguistics in Delhi University (DU). He is also a linguist, an anti-caste scholar, and a social activist. His work as an activist has been largely related to the pro-reservation movement in Indian universities. He is the coordinator of the Alliance of Social Justice, a member of the Joint Action Front for Democratic Education and, until his arrest, he was leading the Defense Committee for GN Saibaba, a professor convicted for alleged links with the Maoist movement.

Babu grew up in the Malabar area of Kerala as a Moplah Muslim belonging to Other Backward Class (OBC – this refers to social groups that are marginalized by systematic oppression and entitled to affirmative action from Indian state). He studied at the Hyderabad campus of English and Foreign Languages University (EFLU) where his journey as a successful Dalit-Bahujan (an umbrella term for marginalized groups in India) academic began: he belongs to the first generation of students who accessed higher education after the Mandal Commission (1990) recommended affirmative action for OBCs in Indian universities. Internationally renowned for his work on linguistics and the recipient of the Best Young Linguist award, Babu worked in several German universities from 1997 to 2001. He then joined the Hyderabad campus of EFLU as an Assistant Professor of Linguistics in 2002 and became one of the first OBC candidates to be employed there after the implementation of Mandal Commission.

Hany Babu moved to Delhi in 2008 when he was appointed as a professor in DU where, as an activist, he worked towards securing academic rights of OBC students through the proper implementation of reservation policies. His work as a professor, his pedagogical practice and his activism were heavily influenced by the Ambedkarite idea of total revolution. As the secretary of Academic Forum for Social Justice, a forum for OBC teachers, he collected data from 30 colleges of DU and exposed the huge gap that exists between the seats allocated for OBC students and those filled. He also protested for the proper implementation of reservation for OBC students in DU, undertook successful litigation against the discriminatory practices in the admission process for OBC students and tried to make the syllabus more inclusive for Dalit-Bahujans. He also drafted the rules for the election to the student-faculty body of DU to ensure representation from all sections of society.

Babu is a strong proponent of using English as a tool to liberate Dalit-Bahujans. His work, as an anti-caste scholar, focuses on the ideology of language, linguistic identity, marginalized languages and social justice. His writings on caste and Indian languages concentrate on the problems of Indian language policies.

Babu’s house was raided early morning on 10 September 2019 for his alleged connections in the Bhima Koregaon-Elgaar Parishad case even though he was not present in Koregaon when the incident took place. The raid was carried out without a search warrant, in violation of both due procedure and Babu’s civil rights. The raid went on for six hours during which Babu, his wife and daughter were physically held, and their phones confiscated. Babu was forced to give permanent access of his email account and social media handles. He was questioned about his participation in the Defense Committee for GN Saibaba and anti-caste movements as well as about his relations with Rona Wilson and Surendra Gadling, two other accused in the Bhima Koregaon-Elgaar Parishad case. His laptop, mobile phones, hard disks, pen drives, two booklets printed for the GN Saibaba Defence Committee and two books were seized. The seized books were From Varna to Jati: Political Economy of Caste in Indian Social Formation by Yalavarthi Naveen Babu and Understanding Maoists: Notes of a Participant Observer from Andhra Pradesh by N. Venugopal. Babu feared that these books would be used to depict him as an academic sympathetic to Maoist and left ideology. He also suspected that some incriminating evidence might be implanted on his devices as their hash value was not provided to him (hash value is a numeric value which identifies and reflects any change that occurred to the data on the devices).

In an interview with the Caravan Magazine, Babu criticized the raid: “If you seize my laptop and mobile phone, I would say it is more of an intimidation. It is precisely because they know how you can cripple an academic, because the hardship I’m going through now for the last two–three months, without access to teaching or research material, this is actually worse than incarceration. If they had locked me up for a week, two weeks, a month, they could do this search while I am inside. That would have been much better. It’s very clear that they are hunting academics, so there is clearly a project to intimidate and silence people.”

Babu was summoned to appear on 15 July 2020 in Mumbai as a witness in the Bhima Koregaon-Elgaar Parishad case on the basis of the data extracted from his seized devices, email and social media handles. Babu requested to appear via video conferencing as travelling during COVID-19 pandemic was a health hazard, but this appeal was denied. Despite maintaining that he had no connection in the Bhima Koregaon-Elgaar Parishad case, Babu travelled to Mumbai on 24 July to appear in front of National Investigation Agency (NIA) in the spirit of cooperation. He was questioned about his relationship with the other accused in the case and about a “hidden folder” found in his laptop, which allegedly contained letters written by Maoists. As the questioning progressed, NIA officers began pressurizing him; he was asked to admit to his own complicity in the case by accepting allegations of being a functionary of Maoist groups. Babu vehemently and persistently denied all allegations, however NIA arrested him after five days of interrogation, on 28 July 2020.

Babu was charged with propagating Naxal activities and Maoist ideology as well as for being a co-conspirator in the Bhima Koregaon-Elgaar Parishad case and remains lodged at Taloja Jail in Maharashtra. NIA later informed Babu’s wife that he was arrested as the “hidden folder” on his laptop established him as a Maoist. His house was raided again on 3 August after his arrest to recover further incriminating evidence including pen drives, one hard disk, and documents related to the Defense Committee for GN Saibaba. Civil society groups of Delhi University and the People’s Union for Civil Liberties condemned the raid in press statements on suspicion of it being a disguise to plant evidence implicating Babu as the hash value of the seized electronic items was never provided.

Date of arrest: 28 July 2020

Charges: Babu was arrested for allegedly supporting Naxal activities, propagating Maoism and being a co-conspirator in the Bhima Koregaon-Elgaar Parishad case. The arrest was made under various charges, including violations of Section 153 (provocation with intent to cause riot), Section 505 (intent to cause harm to the public/army) and Section 117 (abetting commission of offence by the public or by more than ten persons) of the Indian Penal Code. He was also charged under relevant non-bailable sections of Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act and has been taken under extended judicial custody.

Update: Hany Babu remains incarcerated in Taloja Jail where prison authorities denied him access to newspapers and books. He went on a symbolic hunger strike in solidarity with farmers’ protest on 23 December 2020 along with Mahesh Raut, Anand Teltumbde and other accused of the Bhima Koregaon-Elgaar Parishad case.

If you are in a university and oppose state policy, you can be targeted: Hany Babu, DU professor – Excerpt from an interview with Shaheen Ahmed and Maya Palit

The kind of work I am doing, obviously it must have a link to that, because they do not randomly pick people. I think the bulk of my work and engagement has been in issues relating to discrimination, social justice, reservation. But that alone, I am sure, would not have attracted this kind of attention or attack from state agencies. So, there is clearly a kind of message being sent out: that you have to be careful about what kind of activities you are engaged in.

Apart from reservation, another angle which I am working on and have been engaged in is things related to education and education-policy changes. When there was an attempt to launch the four-year undergraduate programme in Delhi University, some of us had very actively opposed it. And we were successful in that. So a lot of my friends also feel the same: given that there is an attempt to overhaul the education policy—maybe not obliterate, but the state universities are being sidelined and there is a watering down of education and maybe scuttling of reservation—all these things are going to come. A lot of changes are going to come, so maybe this is also a kind of signal sent to academics now—I am not saying that it’s attacking me alone—if you are in a university and if you oppose state policy in any way, then you can be targeted.

I can see this now when anything is happening, many of my colleagues and friends in the university are actually thinking twice—earlier they would speak freely against state policy, if there is some change, they would openly attack it. Now they think, “After all, we are government employees.” This concept of being government employees was not there for university teachers, whereas now teachers [think], “Can we criticise the government?” There is this attempt to bring in the civil service—CCS—rules, which govern civil servants. Actually, university teachers are not bound by that. It will basically mean that you cannot oppose the state.

If the raid was about the Elgar Parishad or Bhima Koregaon, I am sure the officers who came know pretty well that I was nowhere in the picture when the meeting was conducted, in preparation for the meeting or after the meeting. I have not even participated in any meetings or corresponded with anyone. Nothing. I am sure they know this. The only connection I kind of see, with some of the people who have also been arrested, is because of my activities with the defence committee. That is what they asked me—very meaningfully they asked, “Do you know Surendra Gadling?” Now Surendra Gadling is a person who has been arrested and he is also the lawyer who was in charge of Saibaba’s case in Nagpur. Obviously I know him because we were part of the defence committee. I have talked to him, called him maybe once or twice. I have also met him once or twice, in Nagpur. I said yes. “Do you know Rona Wilson?” Rona, I also know as a friend. I said, “Yeah, I know him. And so?” After that they do not say anything. Knowing them is enough. By knowing them, with your association with them, you become a suspect for us. They also said that they have some material and I kept asking them, “At least tell me what kind of material, how am I linked to this?” They refused, they kept saying, “We have some material, but we will now look at your records and documents and all and see whether it corroborates. If there is corroboration, we may need to arrest you. Right now we are not arresting you, you are only a suspect, you are not an accused.” So it’s more guilt by association.

The position of law is very clear, there is nothing like guilt by association in our jurisprudence, whereas for the investigating agencies, they work with this. Because if they do not want to punish me, they can very well give me a copy at least, or allow me to take a copy of the material. Let them confiscate my laptop, why can’t they make at least a copy of my material available so that I can work?

Tazeen Junaid is an activist based in Aligarh and writes on issues of gender equity, Indian minorities, and the anti-CAA movement. She is currently pursuing her Bachelors in Literature from Aligarh Muslim University.

SUPPORT US

We like bringing the stories that don’t get told to you. For that, we need your support. However small, we would appreciate it.