“At no time have governments been moralists. They never imprisoned people and executed them for having done something. They imprisoned and executed them to keep them from doing something. They imprisoned all those prisoners of war, of course, not for treason to the motherland […] They imprisoned all of them to keep them from telling their fellow villagers about Europe. What the eye doesn’t see, the heart doesn’t grieve for.”― Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, The Gulag Archipelago, 1918-1956

A political prisoner is a person who is imprisoned for their belief. Regimes across the globe arrest people for who they are and not for what they have done, thus making the category of the political prisoner into a criminal offense. It is a thought crime: the crime of thinking, acting, speaking, probing, reporting, questioning, demanding rights and, more importantly, exercising citizenship. It is also a crime of existing in a Black, Brown, Muslim body that can be targeted and punished for who they are, or what they represent.

These inhumane incarcerations do not just target private acts of courage, they are bound together with the fundamental questions of citizenship, and with people’s capacity to hold the State accountable – especially States that are unilaterally and fundamentally remaking their relationship with their people.

The assault on the fundamental rights has been consistent and ongoing at a global level and rights-bearing citizens are transformed into subjects of a surveillance State.

In this transforming landscape, dissent is sedition, and resistance is treason.

A fearful, weak State silences the voice of dissent. Once it has established repression as a response to critique, it has only one way to go: to become a regime of authoritarian terror, a source of dread and fear for its citizens.

How do we live, survive, and respond to this moment?

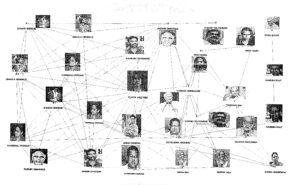

With Profiles of Dissent, The Polis Project works with individuals and organizations across the world to question and critique the State that has used legal means to crush dissent illegally and eliminate questioning voices.

It also intends to ground the idea that, despite the repression, voices of resistance continue to emerge every day.

VERNON GONSALVES

Vernon Gonsalves is a human rights activist, writer and former professor in several colleges in Mumbai. As an advocate of the rights of marginalized communities, he is a vocal critic of India’s criminal justice system and of the State establishment. In 2007, he was imprisoned under the Unlawful Activities Prevention Act (UAPA) and the Arms Act, but he was released in 2013 after most of the charges made against him were disproved in Court. Gonsalves was also a writer and editor in his college days. During his time in prison, he wrote seven short stories related to prison life and after his release, he was commissioned to translate Annabhau Sathe’s story “Gold from the Grave” from Marathi to English for David Davidar’s A Clutch of Indian Masterpieces. He began to regularly co-author articles with Arun Ferriera, who was also arrested in 2003 and similarly acquitted and then arrested again as part of Bhima Koregaon 16 (BK-16). Gonsalves and Ferreira wrote on law and order issues, the prison system — in particular, about under-trials — and the need to repeal the UAPA as well as the other draconian security laws that have vague provisions and give the Indian State extraordinary powers over its own citizens. Gonsalves and Ferreira’s exposition of the undemocratic, authoritarian ways of working of the Indian State and clear elucidation of the complex socio-political-economic power structures that maintain the status quo made their writings among those seen by the establishment as “a force to reckon with.”

Vernon Gonsalves grew up in a chawl in a modest area of Mumbai and graduated in commerce from Mumbai University with flying colors. Soon after, he gave up a promising corporate career to teach in several higher education institutions in the city and work with trade unions and marginalized communities on issues of social justice. For ten years he moved to Chandrapur, over 800 kilometers from Mumbai, to work on labor rights of unorganized workers in the area and subsequently returned to settle in Mumbai. It was in Mumbai in 2007 that he was arrested from his residence and charged with being a Maoist. After being implicated in nearly 17 cases by the State, he was released in 2013 when he was acquitted in all barring two. In one, his appeal against conviction is pending in the High Court and the other case in Surat has been challenged by all the accused including Gonsalves in the Gujarat High Court and the trial is pending.

In 2018, soon after the arrests of the first five BK-16 prisoners, Vernon Gonsalves and Arun Ferreira published a detailed explanation of the obvious contradictions in the incriminating evidence on which the Bhima Koregaon case has been built by the Police and State. They pointed out how a “plot to assassinate the prime minister” was fabricated by the Police to justify the arrests. Drawing on their previous experience, Gonsalves and Ferreira reminded readers of how the Indian State is constructing a “fake political narrative” to target human rights defenders as “urban naxals.” They wrote: “We have had an ample amount of personal experience of bizarre ‘disclosures’ by investigating authorities at the time of our arrests. The so-called evidence is leaked to the press and wild allegations are made, which promptly disappear at the time of trial.” Shortly after, both activists were arrested as part of the same fabricated plot.

Date of arrest: 28 August 2018

Charges: Vernon Gonsalves is among the five human rights activists who were targeted in the second round of the Bhima Koregaon arrests (the others are Gautam Navalakha, Sudha Bharadwaj, Varavara Rao and Arun Ferreira). The homes of all these activists were raided on 28 August 2018 and then they were arrested. On 29 August, all five activists were placed under house arrest following the direction of the Supreme Court in response to a petition moved by five eminent public intellectuals that the activists were arrested without any credible evidence and as an attempt to stifle dissent. A month later, on 28 September, two members of a three-judge bench ruled that the Court would not interfere with this investigation. The third judge gave a dissenting opinion and after four weeks, on 27 October, Gonsalves was taken into police custody along with Arun Ferriera and Sudha Bhardwaj. Varavara Rao remained in “house arrest” for one more month and Gautam Navlakha was given a reprieve from arrest till April 2020. A chargesheet naming all four activists (supplementary to the first one filed by the Police in the case against the first five arrestees), however, was only filed on 21 February 2019. The chargesheet alleges their connection to the Elgar Parishad held on 31 December 2018 and inciting violence in the commemorative event at Bhima Koregaon, in Maharashtra, on the following day. In January 2020, the case was transferred to the National Investigating Agency (NIA), which filed a chargesheet against seven more persons who were also then arrested. The charges have been filed by the NIA under several sections of the Indian Penal Code (including sections pertaining to waging war against State, sedition, statements promoting mischief, abetting commission of offence and criminal conspiracy and common intention) and under the UAPA (such as punishment for terrorist activities and punishment for being part of terrorist organization).

A judicial commission set up by the Government of Maharashtra on 19 February 2018 to probe the violence has yet to submit its report. The panel has asked for extension nine times due to reasons such as Covid-19, lack of human resources and office space.

The charges brought against Vernon Gonsalves and 15 others were on the basis of a bunch of letters that has been rejected by security experts noting that “[a]nyone familiar with the patterns of communication adopted by the Maoists would immediately reject this letter as an obvious fabrication.” More evidence that the BK-16 are all “victims of an elaborate [fictional] plot” emerged in 2021 from the forensic analysis of the harddisks of two other BK-16 political prisons, Rona Wilson and Surendra Gadling by US-based firm Arsenal Consulting. The reports revealed the letters were planted using highly sophisticated malware and surveillance techniques by a third party.

Update: The frequent disruption to family and lawyers visits caused by the pandemic (with closure of Courts and suspension of the meeting arrangement in prison) continued till mid-February 2022. As part of this, during the height of the second Covid-19 wave in 2020, letters sent by and to some of the prisoners reached after extraordinary delays because they were being withheld by prison officials. Vernon Gonsalves’s wife and lawyer Susan Abraham was a co-petitioner along with Rama Teltumbde, wife of Anand Teltumbde, in a case filed against the jail authorities by family members in the Bombay High Court.

During this time, Gonsalves helped to look after fellow under-trial Varavara Rao when he caught Covid, before he was finally released on medical bail in February 2021. The reduced communication in this period caused additional stress to both the prisoners and their families. In October 2021, Vernon Gonsalves was one of the seven BK-16 under-trials to be moved into solitary confinement purportedly to ensure safety as the barracks are over-crowded.

In December 2021, Sudha Bharadwaj, was granted default bail on technical grounds. The others were refused “on the ground that they had not filed their default bail applications within the stipulated period, which is after 60 days of their arrest and before filing of the charge sheet.” However, all the remaining eight accused had indeed filed default bail applications in the stipulated period and are now litigating for release on parity – Surendra Gadling and four others in the NIA Court and Varavara Rao, Vernon Gonsalves and Arun Ferreira in the High Court.

Also in February 2021, Gonsalves’ phone was included in the list of BK-16 phones seized by the Pune Police and on request of the special NIA court they were submitted to the technical committee to investigate possible snooping by the State using the Israeli spyware Pegasus.

An excerpt from When the Police acts above the law by Vernon Gonsalves and Arun Ferreira

[…] Gajala Gopanna, during almost seven and half years in jail, was known to be a quiet reticent type, blending easily with the hundreds of other under trial prisoners he was lodged with. The superintendent of the Jagdalpur Central Prison in Bastar, Chhattisgarh himself confirmed this to the press on September 30, 2014, the day of his release. During the few minutes that Gopanna then got to speak to the press at the prison gates, he said that he planned to go back to agriculture in his village in Nalgonda, Telangana.

But that was not to be. The Chhattisgarh police had, when they arrested him in early May 2007, projected him as a fierce Naxalite leader, personally involved in many violent incidents. Fifteen trials in courts in various districts had proved these claims to be quite hollow; but they were in no mood to bow to the courts’ common verdict of acquittal.

So, as Gopanna was driven off through the streets of Jagdalpur on his lawyer’s motorbike, he was followed, intercepted and rearrested by a police posse. They claimed his custody on the basis of warrants that had been applied for and obtained by them over seven years ago, but had been deliberately kept aside to be used on just such an occasion. The police officers even now do not disclose how many warrants they are going to use – five, six or more. Considering the delays in courts, this re-arrest quite easily means a few more years in jail for Gopanna; and after acquittal and release, there could yet be another round of re-arrest.

The blatant injustice of such a deliberate ploy by the police to indefinitely extend the imprisonment of Gopanna despite his acquittal by the courts is however not something very unusual. It is known to be used in most countries where the police exercise much greater powers than are assigned to them by law. In the US the practice is so rife as to have earned a place for itself in American prison slang; it is called “gate-ing – to confront someone at the gate with new charges”. Protest singer Joan Baez too tells about it in her Prison Trilogy composition, which is based on true stories from prisons where her husband, David Harris, was .jailed in 1969-70 for resisting the Vietnam war draft The third part of her trilogy tells the tale of Kilowatt, the 65-year-old “aging con”, who, “on the day of his release … was approached by the police” to “claim another 10 years of (his) life.”

Here in India the practice is widespread, particularly for political prisoners. During the time spent by the two of us at Nagpur Central Prison, where a large number of prisoners implicated in naxalite related cases were lodged, there was a dedicated police squad deployed at the gates to monitor the releases and, where possible, to ensure the re-arrest of political prisoners. Sometimes, re-arrest in new cases would be done just before the judgment in old cases; at other times, as in Gopanna’s case, the old warrants would be fished out and executed on the day of release; but most of the time, the re-arrests took the form of sheer abduction – as in the case of one of us, Arun Ferreira.

On 27th September, 2011, Arun, after acquittal in eight cases, happily bowed through the prison’s wicket gate for what he thought was the last time. But, even before his foot could settle on the free earth outside the gate, he was literally lifted off the ground by a group of muscular plain clothed young men, thrust forcibly into an un-numbered car and whisked away in the presence of his parents, brother and lawyers. He was later shown to have been arrested somewhere in another district and was implicated in two new cases. There was no warrant, not even an explanation of the cause of detention. It was abduction pure and simple, but both, the jail authorities on whose premises it happened, and the local police station within whose jurisdiction it took place, were complicit, .and refused to even receive a complaint Arun’s abduction scenario is again no exception, but one among many that are regularly played out at prison gates in various parts of the country. Most happen unseen and remain unnoticed. But there have even been cases where abductions have even been done in full media glare. Mallesh Kusma was one such prisoner in Nagpur Prison, who achieved final release only after going through three rounds of abduction type re-arrests – one of which has a detailed photographic record. Sheila Marandi, a tribal woman in her late fifties, has been acquitted or obtained bail in over ten cases but continues to remain in jail in Jharkhand for the last eight years due to four re- arrests at the gates. There are many more.

Related Posts

Exposing the machinations of authoritarian power: A profile of Vernon Gonsalves

VERNON GONSALVES

Vernon Gonsalves is a human rights activist, writer and former professor in several colleges in Mumbai. As an advocate of the rights of marginalized communities, he is a vocal critic of India’s criminal justice system and of the State establishment. In 2007, he was imprisoned under the Unlawful Activities Prevention Act (UAPA) and the Arms Act, but he was released in 2013 after most of the charges made against him were disproved in Court. Gonsalves was also a writer and editor in his college days. During his time in prison, he wrote seven short stories related to prison life and after his release, he was commissioned to translate Annabhau Sathe’s story “Gold from the Grave” from Marathi to English for David Davidar’s A Clutch of Indian Masterpieces. He began to regularly co-author articles with Arun Ferriera, who was also arrested in 2003 and similarly acquitted and then arrested again as part of Bhima Koregaon 16 (BK-16). Gonsalves and Ferreira wrote on law and order issues, the prison system — in particular, about under-trials — and the need to repeal the UAPA as well as the other draconian security laws that have vague provisions and give the Indian State extraordinary powers over its own citizens. Gonsalves and Ferreira’s exposition of the undemocratic, authoritarian ways of working of the Indian State and clear elucidation of the complex socio-political-economic power structures that maintain the status quo made their writings among those seen by the establishment as “a force to reckon with.”

Vernon Gonsalves grew up in a chawl in a modest area of Mumbai and graduated in commerce from Mumbai University with flying colors. Soon after, he gave up a promising corporate career to teach in several higher education institutions in the city and work with trade unions and marginalized communities on issues of social justice. For ten years he moved to Chandrapur, over 800 kilometers from Mumbai, to work on labor rights of unorganized workers in the area and subsequently returned to settle in Mumbai. It was in Mumbai in 2007 that he was arrested from his residence and charged with being a Maoist. After being implicated in nearly 17 cases by the State, he was released in 2013 when he was acquitted in all barring two. In one, his appeal against conviction is pending in the High Court and the other case in Surat has been challenged by all the accused including Gonsalves in the Gujarat High Court and the trial is pending.

In 2018, soon after the arrests of the first five BK-16 prisoners, Vernon Gonsalves and Arun Ferreira published a detailed explanation of the obvious contradictions in the incriminating evidence on which the Bhima Koregaon case has been built by the Police and State. They pointed out how a “plot to assassinate the prime minister” was fabricated by the Police to justify the arrests. Drawing on their previous experience, Gonsalves and Ferreira reminded readers of how the Indian State is constructing a “fake political narrative” to target human rights defenders as “urban naxals.” They wrote: “We have had an ample amount of personal experience of bizarre ‘disclosures’ by investigating authorities at the time of our arrests. The so-called evidence is leaked to the press and wild allegations are made, which promptly disappear at the time of trial.” Shortly after, both activists were arrested as part of the same fabricated plot.

Date of arrest: 28 August 2018

Charges: Vernon Gonsalves is among the five human rights activists who were targeted in the second round of the Bhima Koregaon arrests (the others are Gautam Navalakha, Sudha Bharadwaj, Varavara Rao and Arun Ferreira). The homes of all these activists were raided on 28 August 2018 and then they were arrested. On 29 August, all five activists were placed under house arrest following the direction of the Supreme Court in response to a petition moved by five eminent public intellectuals that the activists were arrested without any credible evidence and as an attempt to stifle dissent. A month later, on 28 September, two members of a three-judge bench ruled that the Court would not interfere with this investigation. The third judge gave a dissenting opinion and after four weeks, on 27 October, Gonsalves was taken into police custody along with Arun Ferriera and Sudha Bhardwaj. Varavara Rao remained in “house arrest” for one more month and Gautam Navlakha was given a reprieve from arrest till April 2020. A chargesheet naming all four activists (supplementary to the first one filed by the Police in the case against the first five arrestees), however, was only filed on 21 February 2019. The chargesheet alleges their connection to the Elgar Parishad held on 31 December 2018 and inciting violence in the commemorative event at Bhima Koregaon, in Maharashtra, on the following day. In January 2020, the case was transferred to the National Investigating Agency (NIA), which filed a chargesheet against seven more persons who were also then arrested. The charges have been filed by the NIA under several sections of the Indian Penal Code (including sections pertaining to waging war against State, sedition, statements promoting mischief, abetting commission of offence and criminal conspiracy and common intention) and under the UAPA (such as punishment for terrorist activities and punishment for being part of terrorist organization).

A judicial commission set up by the Government of Maharashtra on 19 February 2018 to probe the violence has yet to submit its report. The panel has asked for extension nine times due to reasons such as Covid-19, lack of human resources and office space.

The charges brought against Vernon Gonsalves and 15 others were on the basis of a bunch of letters that has been rejected by security experts noting that “[a]nyone familiar with the patterns of communication adopted by the Maoists would immediately reject this letter as an obvious fabrication.” More evidence that the BK-16 are all “victims of an elaborate [fictional] plot” emerged in 2021 from the forensic analysis of the harddisks of two other BK-16 political prisons, Rona Wilson and Surendra Gadling by US-based firm Arsenal Consulting. The reports revealed the letters were planted using highly sophisticated malware and surveillance techniques by a third party.

Update: The frequent disruption to family and lawyers visits caused by the pandemic (with closure of Courts and suspension of the meeting arrangement in prison) continued till mid-February 2022. As part of this, during the height of the second Covid-19 wave in 2020, letters sent by and to some of the prisoners reached after extraordinary delays because they were being withheld by prison officials. Vernon Gonsalves’s wife and lawyer Susan Abraham was a co-petitioner along with Rama Teltumbde, wife of Anand Teltumbde, in a case filed against the jail authorities by family members in the Bombay High Court.

During this time, Gonsalves helped to look after fellow under-trial Varavara Rao when he caught Covid, before he was finally released on medical bail in February 2021. The reduced communication in this period caused additional stress to both the prisoners and their families. In October 2021, Vernon Gonsalves was one of the seven BK-16 under-trials to be moved into solitary confinement purportedly to ensure safety as the barracks are over-crowded.

In December 2021, Sudha Bharadwaj, was granted default bail on technical grounds. The others were refused “on the ground that they had not filed their default bail applications within the stipulated period, which is after 60 days of their arrest and before filing of the charge sheet.” However, all the remaining eight accused had indeed filed default bail applications in the stipulated period and are now litigating for release on parity – Surendra Gadling and four others in the NIA Court and Varavara Rao, Vernon Gonsalves and Arun Ferreira in the High Court.

Also in February 2021, Gonsalves’ phone was included in the list of BK-16 phones seized by the Pune Police and on request of the special NIA court they were submitted to the technical committee to investigate possible snooping by the State using the Israeli spyware Pegasus.

An excerpt from When the Police acts above the law by Vernon Gonsalves and Arun Ferreira

[…] Gajala Gopanna, during almost seven and half years in jail, was known to be a quiet reticent type, blending easily with the hundreds of other under trial prisoners he was lodged with. The superintendent of the Jagdalpur Central Prison in Bastar, Chhattisgarh himself confirmed this to the press on September 30, 2014, the day of his release. During the few minutes that Gopanna then got to speak to the press at the prison gates, he said that he planned to go back to agriculture in his village in Nalgonda, Telangana.

But that was not to be. The Chhattisgarh police had, when they arrested him in early May 2007, projected him as a fierce Naxalite leader, personally involved in many violent incidents. Fifteen trials in courts in various districts had proved these claims to be quite hollow; but they were in no mood to bow to the courts’ common verdict of acquittal.

So, as Gopanna was driven off through the streets of Jagdalpur on his lawyer’s motorbike, he was followed, intercepted and rearrested by a police posse. They claimed his custody on the basis of warrants that had been applied for and obtained by them over seven years ago, but had been deliberately kept aside to be used on just such an occasion. The police officers even now do not disclose how many warrants they are going to use – five, six or more. Considering the delays in courts, this re-arrest quite easily means a few more years in jail for Gopanna; and after acquittal and release, there could yet be another round of re-arrest.

The blatant injustice of such a deliberate ploy by the police to indefinitely extend the imprisonment of Gopanna despite his acquittal by the courts is however not something very unusual. It is known to be used in most countries where the police exercise much greater powers than are assigned to them by law. In the US the practice is so rife as to have earned a place for itself in American prison slang; it is called “gate-ing – to confront someone at the gate with new charges”. Protest singer Joan Baez too tells about it in her Prison Trilogy composition, which is based on true stories from prisons where her husband, David Harris, was .jailed in 1969-70 for resisting the Vietnam war draft The third part of her trilogy tells the tale of Kilowatt, the 65-year-old “aging con”, who, “on the day of his release … was approached by the police” to “claim another 10 years of (his) life.”

Here in India the practice is widespread, particularly for political prisoners. During the time spent by the two of us at Nagpur Central Prison, where a large number of prisoners implicated in naxalite related cases were lodged, there was a dedicated police squad deployed at the gates to monitor the releases and, where possible, to ensure the re-arrest of political prisoners. Sometimes, re-arrest in new cases would be done just before the judgment in old cases; at other times, as in Gopanna’s case, the old warrants would be fished out and executed on the day of release; but most of the time, the re-arrests took the form of sheer abduction – as in the case of one of us, Arun Ferreira.

On 27th September, 2011, Arun, after acquittal in eight cases, happily bowed through the prison’s wicket gate for what he thought was the last time. But, even before his foot could settle on the free earth outside the gate, he was literally lifted off the ground by a group of muscular plain clothed young men, thrust forcibly into an un-numbered car and whisked away in the presence of his parents, brother and lawyers. He was later shown to have been arrested somewhere in another district and was implicated in two new cases. There was no warrant, not even an explanation of the cause of detention. It was abduction pure and simple, but both, the jail authorities on whose premises it happened, and the local police station within whose jurisdiction it took place, were complicit, .and refused to even receive a complaint Arun’s abduction scenario is again no exception, but one among many that are regularly played out at prison gates in various parts of the country. Most happen unseen and remain unnoticed. But there have even been cases where abductions have even been done in full media glare. Mallesh Kusma was one such prisoner in Nagpur Prison, who achieved final release only after going through three rounds of abduction type re-arrests – one of which has a detailed photographic record. Sheila Marandi, a tribal woman in her late fifties, has been acquitted or obtained bail in over ten cases but continues to remain in jail in Jharkhand for the last eight years due to four re- arrests at the gates. There are many more.

SUPPORT US

We like bringing the stories that don’t get told to you. For that, we need your support. However small, we would appreciate it.