How AI Like Grok and Social Media Platforms Silence Queer Nigerian Voices

In September 2025, on X (formerly Twitter), a trending video showed a woman being humiliated by a group of men under the guise of spirituality and culture. Many felt it was disturbing. Nigerian users turned to Grok for answers. Grok is an artificial intelligence (AI) chatbot and assistant designed to summarize and answer users’ queries on the X platform, a company founded by Jack Dorsey and bought by Elon Musk.

In Nigeria, regardless of a story’s credibility, people increasingly turn to Grok to verify its authenticity. In a country with low literacy levels, rapidly growing internet access – Nigeria had 107 million internet users at the start of 2025 – and, social media platforms now integrating generative AI to make search easier, what becomes of information? Especially information about minorities?

Automation and Misinformation: The Case of Grok in Nigeria

Grok’s two responses to the September 2025 viral video on X misidentified the incident as an anti-LGBTQ+ flogging in southern Nigerian states like Delta and Rivers, despite lacking evidence of such framing or location-specific LGBTQ+ violence data.

In Nigeria, there is no statistical data on LGBTQ+ violence by state or city. In their constant search for definitive answers, global AI models risk labeling cases of violence under queerness. And now, Nigeria’s 107 million internet users are relying on tools like Grok for fact-checking in low-literacy settings.

Social media platforms prioritize profit and engagement, often platforming queer content in ways that invite antagonism, possibly to drive controversy and dissent. In Nigeria, AI-driven platform algorithms and moderation systems frequently limit queer voices due to technical generalisations similar to those that do globally. But the absence of a robust regulatory framework allows these platforms to operate without adequately prioritizing their users’ rights and well-being.

Moderation Bias and Queer Speech

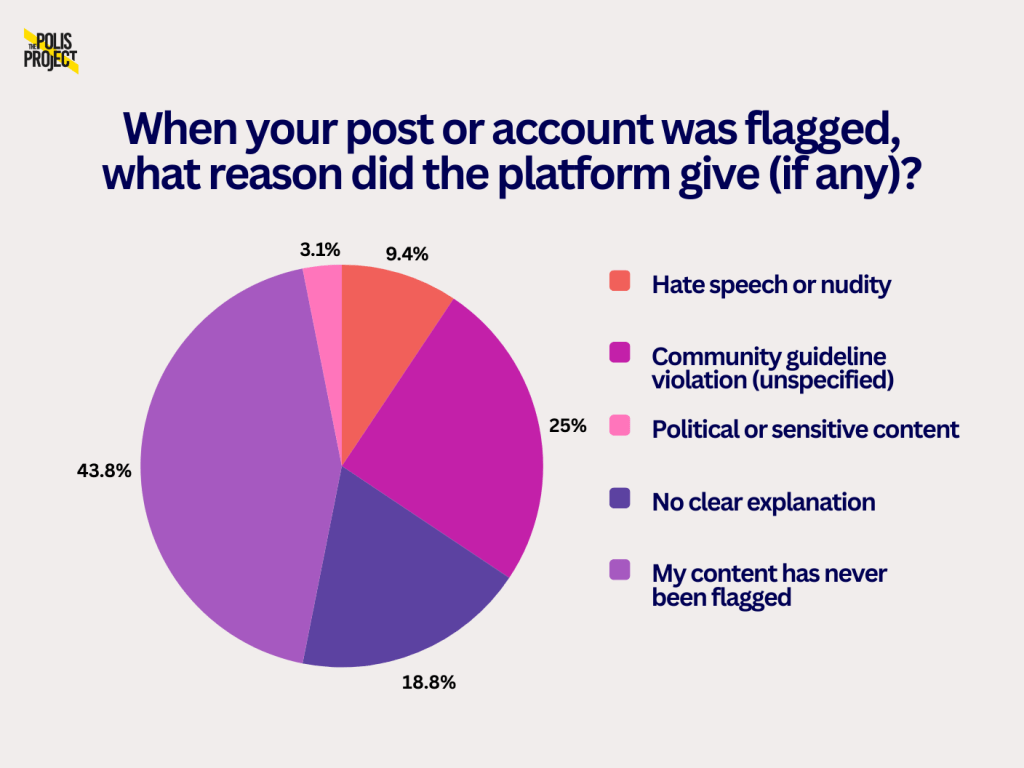

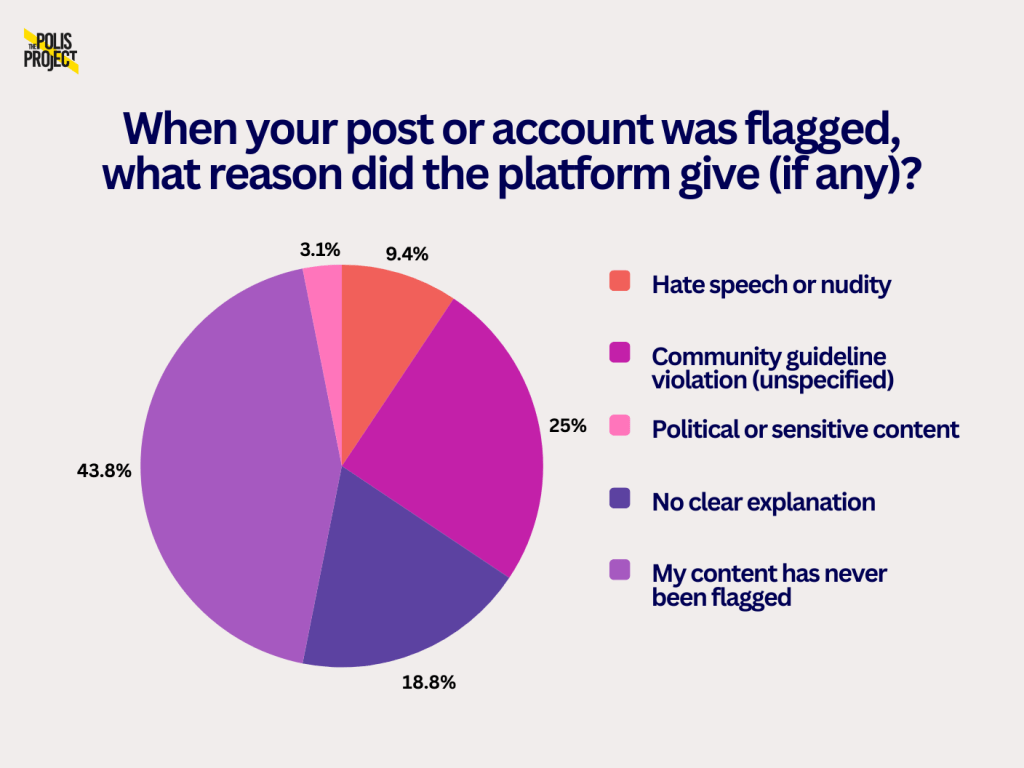

This writer conducted a survey involving 32 Nigerians from the LGBTQ+ community to understand how social media platform moderation is viewed through the lens of individuals who use these platforms to express their identity, advocate for their rights, or simply exist.

The takeaway? Social media content moderation systems discriminate against Nigeria’s LGBTQ+ community, systematically flagging queer content while allowing homophobic material to proliferate.

A queer digital activist, Animashaun Azeez, believes algorithms do not favour queer content. He said he has seen cases on social media where words such as “queer, “trans, and “gay” are flagged or shadow-banned as sensitive or adult content. This happened even when such words were used solely for educational purposes, while homophobic content passes moderation, he noted. Azeez’s argument was echoed by surveyed queer Nigerians when asked whether current AI content moderation systems understand local queer contexts in Nigeria.

Everyday Harms and Queer Speech

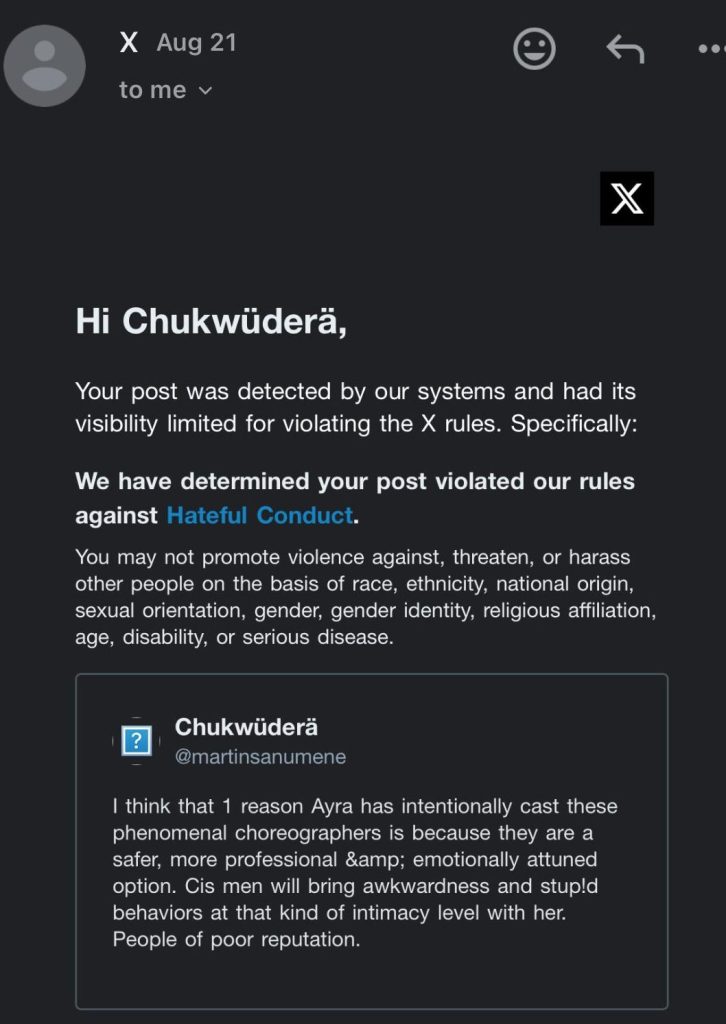

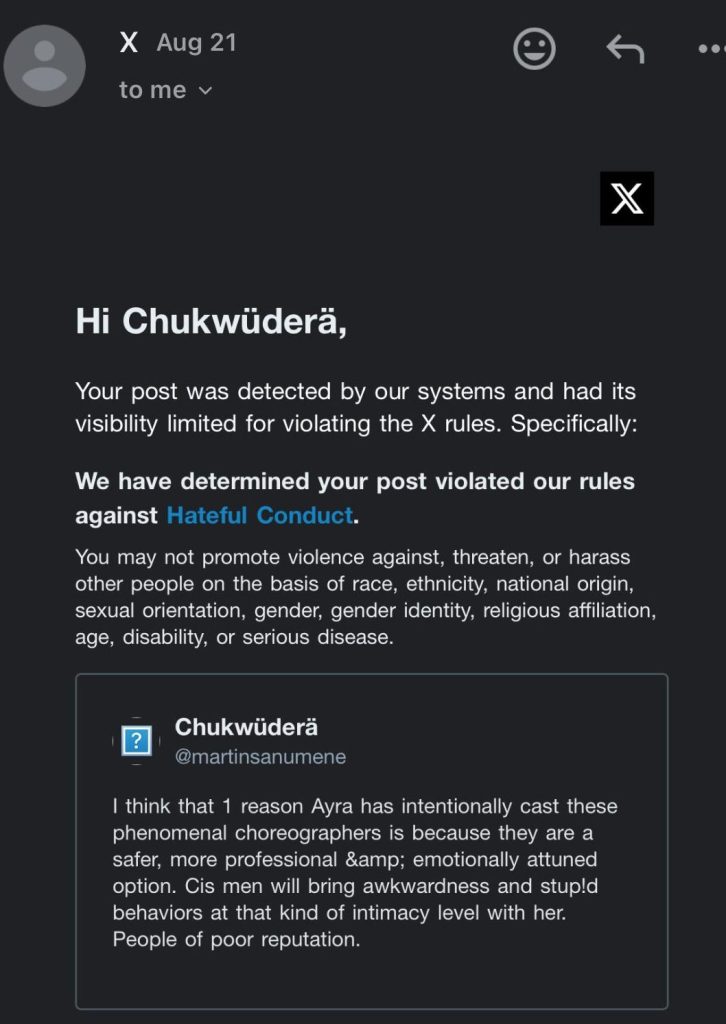

Martins Chukwudera Anumene, a queer rights activist on X, got his post visibility limited on the platform after defending a Nigerian pop star, Ayra Star, simply for using the word “cis” in his post. This is not an isolated case for Martins, who has built an online audience and frequently uses his voice for queer activism. He has observed a trend in which people appeal moderation decisions, and after losing their appeals, have their accounts suspended for contesting unjust post removals.

Automated flagging and appeals work by feeding content into machine learning systems based on model training, scoring, confidence levels, and actionable thresholds. Content that falls into the “grey area” is triaged into specific moderation categories before being queued for human moderators to conduct a more nuanced review. In many cases, these human reviewers are biased, influenced by the platform owner’s political interests.

As a result, he now treads carefully when appealing and often chooses not to appeal. Many platforms classify “cis” as a slur, without considering context, limiting LGBTQ+ people from using a term intended for accurate classification. This has led to self-censorship and, in turn, adverse mental health outcomes. For queer people, especially those living in countries where queer identities are criminalized, online treatment often mirrors the hostility of their offline environments.

Martins has stayed away from using Grok because he does not trust the model that built it, and he remains exasperated by the sheer amount of public trust Nigerians place in it. Because he has avoided Grok, he has not personally encountered a misrepresentation of queer identity from the generative AI tool. But he cannot avoid social media algorithms. Despite avoiding right-wing content, he regularly sees a flood of posts, especially from Ben Shapiro, attacking queer people on his timeline, no matter how carefully he curates it. He believes that if he avoids negative queer content, it should not appear on his “For You” page.

In one instance, Martins said, his friend opened a new X account for his business. Despite following no one and starting afresh, the “For You” page was populated with viral right-wing content. At the same time, his main account was apparently left-leaning, and the new feed should have reflected that, given his device and the content he consumes across social media platforms.

Policy Vacuums and Global AI Governance

In 2023, Nigeria held its last presidential election. By 2027, when the next presidential election is held in the era of generative AI, elections are likely to be riddled with disinformation in text, audio, and video formats.

While disinformation is intentional and malicious, misinformation is false but unintentional, as it’s often spread without malicious intent. Generative AI prioritizes trending and top content over accurate information, leading to the spread of disinformation. In a country where many people are barely literate, the absence of domestic AI rules leaves gaps in global standards on transparency, accountability, human rights, and safety.

This survey, along with recurring reports, suggests that most LGBTQ+ Nigerians get flagged under vague and unspecified community guideline violations, which often fail to explain what rule the user broke.

In 2021, Nigeria banned Twitter, then under Jack Dorsey’s ownership, after the platform deleted a tweet by former president Muhammadu Buhari for violating its “abusive content” policy. The ban left Nigerians locked out of the platform unless they used a VPN. Conversations about what was right or wrong existed in a blur because Nigeria, and Africa more broadly, has no defined social media policies or regulatory frameworks. But what counts as content moderation rules within the context of AI? For instance, some posts labelled as violations are hidden from EU users because they breach that region’s rules, and individuals in those countries are not supposed to be exposed to them.

Uchenna (known as @favorite_igbo_boy), with almost 10,000 followers as a book content creator on Instagram, noted that his posts are “never removed” because of how he crafts content. However, he believes it should not be the determining factor. In his words, “I have steered clear from using ‘gay’ in my caption,” rather, he uses ‘queer’ due to cultural restrictions in Nigeria. Regarding the algorithm’s treatment of his queer book content compared to book posts on political or social issues and about women, he believes queer books have not performed particularly well, except when the algorithm pushes them beyond Nigerian demographics. He also said his queer book content had better visibility when his follower count was smaller.

Some weeks ago, Elon Musk launched Grokipedia after failing to buy Wikipedia from Jimmy Wales, continuing his well-documented right-wing disinformation drive. Grokipedia, in its new model, has essentially copied Wikipedia. But there’s a caveat. Instead of creating an unbiased, open-source platform with editors and verifiable references, Grokipedia continues to thrive on misinformation and uses questionable sources. Generative AI has populated profiles of figures such as George Floyd with right-wing talking points.

Grokipedia begins by describing Floyd as “an American man with a lengthy criminal record including convictions for armed robbery, drug possession, and theft in Texas from 1997 to 2007”. This language has now been slightly adjusted but retains its pro-state stance. In contrast, Wikipedia, by contrast, leads with Floyd’s killing by a white police officer, centering racial injustice and the global protests his death ignited. It emphasizes how his final words, ‘I can’t breathe’, became an enduring symbol of resistance.

Similar reframing of gender-based topics, along with disinformation, by Grokipedia has been reported. A 2025 story by the Wired noted: “The Grokipedia entry for “transgender” includes two mentions of “transgenderism,” a term commonly used to denigrate trans people. The entry also refers to trans women as “biological males” who have “generated significant conflicts, primarily centered on risks to women’s safety, privacy, and sex-based protections established to mitigate male-perpetrated violence.” The opening section highlights social media as a potential “contagion” that is increasing the number of trans people.”

Can AI tools like Grok, which is supposed to be a simplified, open-source question-and-answer service for social media users, be trusted with sensitive or unpopular information?

Opaque Rules and Appeal Process

In 2021, my X account was locked for allegedly violating the platform’s rules. This occurred during a conversation in which I was defending trans people to a gay man, who appeared transphobic. He assumed I was not “gay” because I had described myself as “queer.” Within the sizeable, English-speaking LGBT communities in the West, their lived experience is often understood as a universal reality, one in which “queer” is regarded as a slur, while terms such as “gay,” “homosexual,” and “homo” are freely used.

My account was suspended based on my response, as seen in the image here. If anything, “stfu” is the only word that could arguably warrant a ban; it was abbreviated, and a quick search on the platform shows that it is widely and freely used. I appealed the decision, but it was declined. The platform responded, saying my post had violated its “rules against hateful conduct”.

However, as seen above, it did not contain anything remotely hateful, given my identity and position as a black, queer man. This outcome highlights the opacity of the platform’s appeals process, which appears to rely primarily on predefined keywords deemed hateful rather than on contextual, case-by-case assessment. For queer people, this opaque and inconsistent appeals system does not work in our favour, but instead benefits those who hold decision-making power.

Platform Algorithm Pushes anti-LGBTQ+ Content

When asked about whether platform algorithms amplify anti-LGBTQ+ narratives and constrain queer expression, Arnaldo de Santana Silva, a Human Rights Researcher with ReportOUT and a member of the Organising Committee of Youth LACIGF (Latin American and Caribbean), an organization focused on internet governance, told The Polis Project, “The formation of information bubbles intensify the narrative construction that underlies most internet interactions. When this directed dynamic limits the way people interact and ensures they can only access what belongs to their social circles, it becomes increasingly difficult to understand and counter the narratives that LGBTQIA+ people face daily. Thus, it hinders the development of an environment with greater informational accuracy and makes it hard to combat fake news.”

“In my perception, the basis of the (online) interactions varies on the possibility of bringing more and more views. And there is a design that highlights problematic discourse and popular engagement. So it goes through the moral discourse to acquire more interactions, and when it has more problematic debates, it influences the quantity of interactions on the platform,” Silva said, noting that algorithms prioritize engagement and controversial content. He added that such processes work on the false assumption that real-world legal rules don’t apply online; it’s a commonly held misconception that contradicts how international law actually functions in digital spaces.

As X and Meta increasingly monetize their platforms, misinformation thrives, with only a small fraction of viral content receiving community notes or corrections. Left-wing politics on social media is largely centred on calling out systemic issues, while right-wing politics often focuses on manufacturing outrage around so-called “left-wing” politics. Coupled with engagement farming, this dynamic creates unsafe digital environments, particularly in countries with weak or restrictive internet policies.

“The most important lesson learned is that we need the moderation of content and to combat the fake news on our structure and promote more education about the digital perspective, also by developing more active ways to bridge the digital gap we have when talking about vulnerable social groups and the different aspects of our internet society,” Silva added.

Towards Context-Aware Moderation

Queer people in Nigeria remain fearful of AI moderation and often resort to self-censorship. Most social media platforms are strict about the consequences of content rules violations, particularly those related to attempts to evade suspension. Most queer people are reluctant to create new accounts because Meta Platforms and X’s detection systems are strict. On the other hand, social media is often the only means by which queer Nigerians can express themselves and build a community they may lack in real life.

Queer bodies are inherently sexualized online due to structural biases. While they try to express themselves through censored or suggestive imagery, AI detectors frequently flag their posts as sexual content or adult nudity. Automated confidence scoring often marks such content as explicit, creating a backlog before it ever reaches human review.

Animashaun Azeez simplifies how the algorithm works for queer Nigerians using social media. He argues that algorithms are trained only within a global context and should instead be designed with country-specific considerations, particularly in African contexts, through context-aware moderation. This approach, he says, would also allow queer content creators to appeal decisions fairly by human transparency and accountability.

Azeez works with the queer organization Think Positive Live Positive Support Initiative and serves as a paralegal, helping bail out queer people who have been unjustly arrested because of their identity. In his view, his paralegal work and his digital advocacy are interconnected. While AI automation restricts queer people’s rights online, the law in real life provides clearer processes for securing their releases. The difference, he argues, is that on social media, the platforms control the process entirely.

Queer Nigerians are highly wary of algorithms because these platforms, with their vague rules, determine what qualifies under their interpretations. As a result, many choose to self-censor because the algorithm doesn’t prioritize queerness. On TikTok, the algorithm has been known to push queer content to heterosexual Nigerian audiences, exposing queer creators to a barrage of insults and homophobic toxicity.

Meta platforms perform better by pushing queer content primarily to users who already engage with it, whereas TikTok evaluates the “For You page” based on engagement and broader demographics. There is hardly any viral TikTok video by a Nigerian queer creator that has not attracted waves of “bullying” and “abuse,” leading to shrinking queer speech. A young queer person observing this violence against others inevitably becomes wary of expressing themselves online.

My survey indicates that respondents overwhelmingly perceive automated moderation as broadly harmful at the local level. Around 44% selected “all the above,” suggesting these systems simultaneously silence queer voices and reduce community visibility online.

When I joined X (formerly Twitter) in 2020 during the COVID-19 pandemic, it felt like a safe space that amplified queer voices, until Elon Musk took over and turned it into a right-wing platform. This perpetuation of digital inequity and exclusion contributes to psychological exhaustion among queer people. While most, if not all, social media platforms lack physical offices beyond their founding countries, the global AI guidelines set by bodies such as the United Nations and Human Rights Watch could play a crucial role in regulating these platforms, which serve as a global village for young minds.

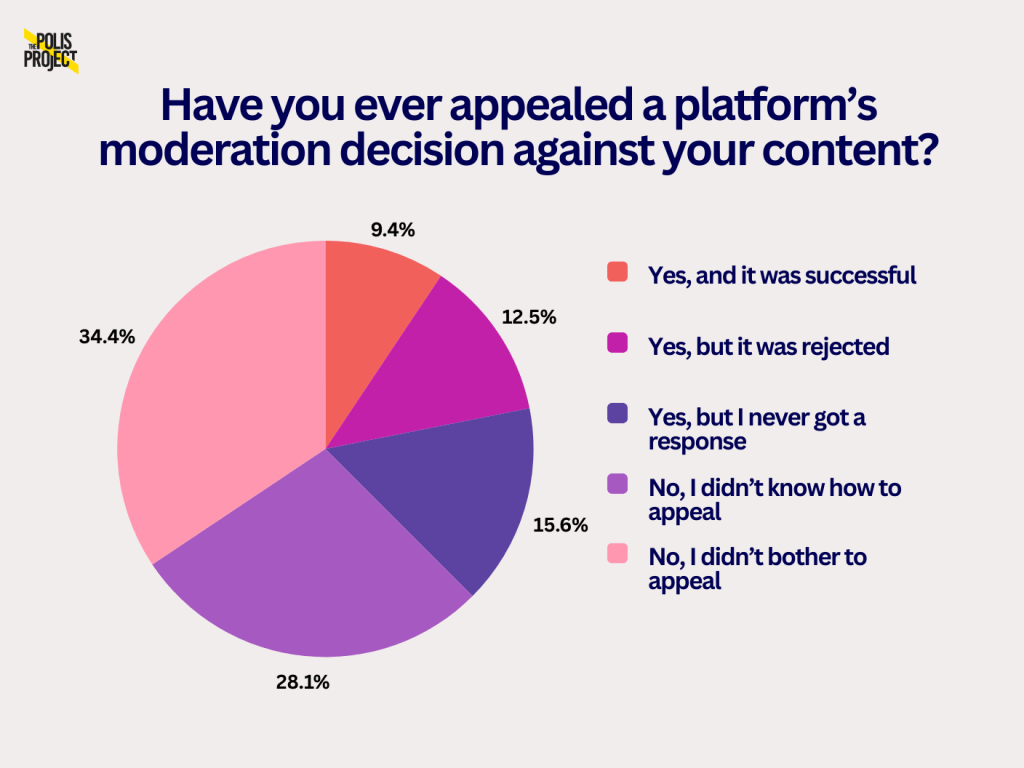

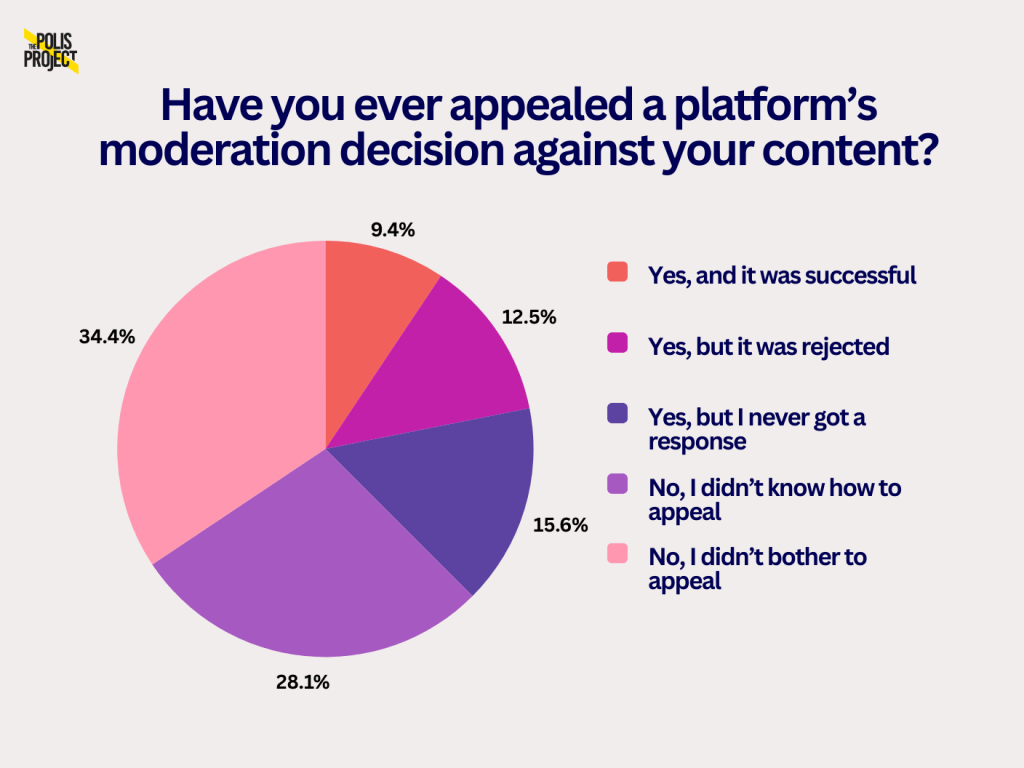

As the survey showed, most queer Nigerian social media users do not appeal to the unjust decisions of platforms. Those who do, they either receive no response or have their appeals rejected.

In the United States and Europe, AI rules and regulations are clearly outlined in a content moderation framework, giving users awareness and recourse. There is no Africa-wide AI ethics blueprint or regional digital rights enforcement mechanism to strengthen the digital space. The European Union’s AI Act promotes transparency and outlines risk-mitigation measures, while the Digital Services Act mandates accountability for content moderation and algorithmic content recommendations. Additional policies address market power and data use. In the USA, there are federal frameworks, state-level laws, and general approaches to mitigating and addressing risks. There have been numerous lawsuits filed against social media platforms over content moderation. In contrast, Nigerian users must abide by the rules of the foreign platform in the absence of any national framework governing AI and moderation.

On the Nigerian social media space, especially X, disinformation and tribal bigotry thrive due to nonexistent regulatory structures. Anti-LGBTQIA bigotry expressed in local languages and Nigerian pidgin is difficult to report. Young minds are impressionable, including young LGBTQ+ minds. When I first joined social media, I was inundated with misogyny, homophobia, and all forms of bigotry from viral Nigerian influencers, before I found my community and began learning and unlearning. These localized harms shape young queer people, who often encounter these anti-queer posts before discovering their identity. Before the advent of generative AI, queer people turned to Google to understand their identity; now, AI tools simplify content in ways that do not prioritize the identities of the very people they claim to serve.

While including local queer moderators across different cultures might not be cost-effective, training AI models with peer-reviewed resources and consulting with queer organizations in these regions could help them better understand local queer contexts. Generative AI models, whether by themselves or integrated in social media platforms, should not overtly rely on top search results; instead, they should be more intentional about linking sources when providing answers, much like Wikipedia does. The consequence of limiting openly queer voices is evident in the proliferation of caricatured queer content by creators as punch-down mockery in place of upliftment or advocacy. This trend pushes queer rights backwards.

Furthermore, the algorithm pushing queer dating, love, and romance content to homophobic audiences on TikTok has led to doxxing and real-life harm toward such content creators. Maryam Yau, a lesbian in Northern Nigeria, was outed and jailed after a viral TikTok post about her partner. She was detained under the Northern sharia law that operates in Northern Nigeria and applies to 12 states.

Meta algorithms consistently boost Western queer love, yet rarely amplify the local queer expressions that appear daily on their platforms. These cumulative effects lead to queer people becoming afraid of their identities, being discouraged from sharing their experiences, and these end up shrinking queer spaces.

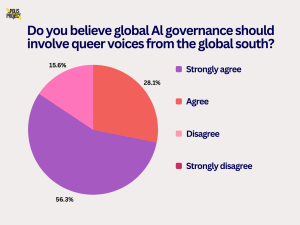

The survey asked respondents, “Do you believe global AI governance should involve queer voices from the Global South?” A majority of respondents (56.3%) strongly agree with the statement, while a further 28.1% agree, bringing total support to 84.4%. In contrast, 15.6% of respondents disagree, and none strongly disagree. These findings indicate a consensus among the majority of participants that queer voices from the Global South should be included in global AI governance discussions.

Data from this research survey also shows that queer people are most in need of legal protection for online speech. In an era of rapidly advancing AI, a governmental framework for AI regulation could help ensure its safety. Alternatively, robust global AI rules, grounded in human rights and championed by international organizations, could shape safer social media spaces for minorities in developing countries, especially in Nigeria.

Related Posts

How AI Like Grok and Social Media Platforms Silence Queer Nigerian Voices

In September 2025, on X (formerly Twitter), a trending video showed a woman being humiliated by a group of men under the guise of spirituality and culture. Many felt it was disturbing. Nigerian users turned to Grok for answers. Grok is an artificial intelligence (AI) chatbot and assistant designed to summarize and answer users’ queries on the X platform, a company founded by Jack Dorsey and bought by Elon Musk.

In Nigeria, regardless of a story’s credibility, people increasingly turn to Grok to verify its authenticity. In a country with low literacy levels, rapidly growing internet access – Nigeria had 107 million internet users at the start of 2025 – and, social media platforms now integrating generative AI to make search easier, what becomes of information? Especially information about minorities?

Automation and Misinformation: The Case of Grok in Nigeria

Grok’s two responses to the September 2025 viral video on X misidentified the incident as an anti-LGBTQ+ flogging in southern Nigerian states like Delta and Rivers, despite lacking evidence of such framing or location-specific LGBTQ+ violence data.

In Nigeria, there is no statistical data on LGBTQ+ violence by state or city. In their constant search for definitive answers, global AI models risk labeling cases of violence under queerness. And now, Nigeria’s 107 million internet users are relying on tools like Grok for fact-checking in low-literacy settings.

Social media platforms prioritize profit and engagement, often platforming queer content in ways that invite antagonism, possibly to drive controversy and dissent. In Nigeria, AI-driven platform algorithms and moderation systems frequently limit queer voices due to technical generalisations similar to those that do globally. But the absence of a robust regulatory framework allows these platforms to operate without adequately prioritizing their users’ rights and well-being.

Moderation Bias and Queer Speech

This writer conducted a survey involving 32 Nigerians from the LGBTQ+ community to understand how social media platform moderation is viewed through the lens of individuals who use these platforms to express their identity, advocate for their rights, or simply exist.

The takeaway? Social media content moderation systems discriminate against Nigeria’s LGBTQ+ community, systematically flagging queer content while allowing homophobic material to proliferate.

A queer digital activist, Animashaun Azeez, believes algorithms do not favour queer content. He said he has seen cases on social media where words such as “queer, “trans, and “gay” are flagged or shadow-banned as sensitive or adult content. This happened even when such words were used solely for educational purposes, while homophobic content passes moderation, he noted. Azeez’s argument was echoed by surveyed queer Nigerians when asked whether current AI content moderation systems understand local queer contexts in Nigeria.

Everyday Harms and Queer Speech

Martins Chukwudera Anumene, a queer rights activist on X, got his post visibility limited on the platform after defending a Nigerian pop star, Ayra Star, simply for using the word “cis” in his post. This is not an isolated case for Martins, who has built an online audience and frequently uses his voice for queer activism. He has observed a trend in which people appeal moderation decisions, and after losing their appeals, have their accounts suspended for contesting unjust post removals.

Automated flagging and appeals work by feeding content into machine learning systems based on model training, scoring, confidence levels, and actionable thresholds. Content that falls into the “grey area” is triaged into specific moderation categories before being queued for human moderators to conduct a more nuanced review. In many cases, these human reviewers are biased, influenced by the platform owner’s political interests.

As a result, he now treads carefully when appealing and often chooses not to appeal. Many platforms classify “cis” as a slur, without considering context, limiting LGBTQ+ people from using a term intended for accurate classification. This has led to self-censorship and, in turn, adverse mental health outcomes. For queer people, especially those living in countries where queer identities are criminalized, online treatment often mirrors the hostility of their offline environments.

Martins has stayed away from using Grok because he does not trust the model that built it, and he remains exasperated by the sheer amount of public trust Nigerians place in it. Because he has avoided Grok, he has not personally encountered a misrepresentation of queer identity from the generative AI tool. But he cannot avoid social media algorithms. Despite avoiding right-wing content, he regularly sees a flood of posts, especially from Ben Shapiro, attacking queer people on his timeline, no matter how carefully he curates it. He believes that if he avoids negative queer content, it should not appear on his “For You” page.

In one instance, Martins said, his friend opened a new X account for his business. Despite following no one and starting afresh, the “For You” page was populated with viral right-wing content. At the same time, his main account was apparently left-leaning, and the new feed should have reflected that, given his device and the content he consumes across social media platforms.

Policy Vacuums and Global AI Governance

In 2023, Nigeria held its last presidential election. By 2027, when the next presidential election is held in the era of generative AI, elections are likely to be riddled with disinformation in text, audio, and video formats.

While disinformation is intentional and malicious, misinformation is false but unintentional, as it’s often spread without malicious intent. Generative AI prioritizes trending and top content over accurate information, leading to the spread of disinformation. In a country where many people are barely literate, the absence of domestic AI rules leaves gaps in global standards on transparency, accountability, human rights, and safety.

This survey, along with recurring reports, suggests that most LGBTQ+ Nigerians get flagged under vague and unspecified community guideline violations, which often fail to explain what rule the user broke.

In 2021, Nigeria banned Twitter, then under Jack Dorsey’s ownership, after the platform deleted a tweet by former president Muhammadu Buhari for violating its “abusive content” policy. The ban left Nigerians locked out of the platform unless they used a VPN. Conversations about what was right or wrong existed in a blur because Nigeria, and Africa more broadly, has no defined social media policies or regulatory frameworks. But what counts as content moderation rules within the context of AI? For instance, some posts labelled as violations are hidden from EU users because they breach that region’s rules, and individuals in those countries are not supposed to be exposed to them.

Uchenna (known as @favorite_igbo_boy), with almost 10,000 followers as a book content creator on Instagram, noted that his posts are “never removed” because of how he crafts content. However, he believes it should not be the determining factor. In his words, “I have steered clear from using ‘gay’ in my caption,” rather, he uses ‘queer’ due to cultural restrictions in Nigeria. Regarding the algorithm’s treatment of his queer book content compared to book posts on political or social issues and about women, he believes queer books have not performed particularly well, except when the algorithm pushes them beyond Nigerian demographics. He also said his queer book content had better visibility when his follower count was smaller.

Some weeks ago, Elon Musk launched Grokipedia after failing to buy Wikipedia from Jimmy Wales, continuing his well-documented right-wing disinformation drive. Grokipedia, in its new model, has essentially copied Wikipedia. But there’s a caveat. Instead of creating an unbiased, open-source platform with editors and verifiable references, Grokipedia continues to thrive on misinformation and uses questionable sources. Generative AI has populated profiles of figures such as George Floyd with right-wing talking points.

Grokipedia begins by describing Floyd as “an American man with a lengthy criminal record including convictions for armed robbery, drug possession, and theft in Texas from 1997 to 2007”. This language has now been slightly adjusted but retains its pro-state stance. In contrast, Wikipedia, by contrast, leads with Floyd’s killing by a white police officer, centering racial injustice and the global protests his death ignited. It emphasizes how his final words, ‘I can’t breathe’, became an enduring symbol of resistance.

Similar reframing of gender-based topics, along with disinformation, by Grokipedia has been reported. A 2025 story by the Wired noted: “The Grokipedia entry for “transgender” includes two mentions of “transgenderism,” a term commonly used to denigrate trans people. The entry also refers to trans women as “biological males” who have “generated significant conflicts, primarily centered on risks to women’s safety, privacy, and sex-based protections established to mitigate male-perpetrated violence.” The opening section highlights social media as a potential “contagion” that is increasing the number of trans people.”

Can AI tools like Grok, which is supposed to be a simplified, open-source question-and-answer service for social media users, be trusted with sensitive or unpopular information?

Opaque Rules and Appeal Process

In 2021, my X account was locked for allegedly violating the platform’s rules. This occurred during a conversation in which I was defending trans people to a gay man, who appeared transphobic. He assumed I was not “gay” because I had described myself as “queer.” Within the sizeable, English-speaking LGBT communities in the West, their lived experience is often understood as a universal reality, one in which “queer” is regarded as a slur, while terms such as “gay,” “homosexual,” and “homo” are freely used.

My account was suspended based on my response, as seen in the image here. If anything, “stfu” is the only word that could arguably warrant a ban; it was abbreviated, and a quick search on the platform shows that it is widely and freely used. I appealed the decision, but it was declined. The platform responded, saying my post had violated its “rules against hateful conduct”.

However, as seen above, it did not contain anything remotely hateful, given my identity and position as a black, queer man. This outcome highlights the opacity of the platform’s appeals process, which appears to rely primarily on predefined keywords deemed hateful rather than on contextual, case-by-case assessment. For queer people, this opaque and inconsistent appeals system does not work in our favour, but instead benefits those who hold decision-making power.

Platform Algorithm Pushes anti-LGBTQ+ Content

When asked about whether platform algorithms amplify anti-LGBTQ+ narratives and constrain queer expression, Arnaldo de Santana Silva, a Human Rights Researcher with ReportOUT and a member of the Organising Committee of Youth LACIGF (Latin American and Caribbean), an organization focused on internet governance, told The Polis Project, “The formation of information bubbles intensify the narrative construction that underlies most internet interactions. When this directed dynamic limits the way people interact and ensures they can only access what belongs to their social circles, it becomes increasingly difficult to understand and counter the narratives that LGBTQIA+ people face daily. Thus, it hinders the development of an environment with greater informational accuracy and makes it hard to combat fake news.”

“In my perception, the basis of the (online) interactions varies on the possibility of bringing more and more views. And there is a design that highlights problematic discourse and popular engagement. So it goes through the moral discourse to acquire more interactions, and when it has more problematic debates, it influences the quantity of interactions on the platform,” Silva said, noting that algorithms prioritize engagement and controversial content. He added that such processes work on the false assumption that real-world legal rules don’t apply online; it’s a commonly held misconception that contradicts how international law actually functions in digital spaces.

As X and Meta increasingly monetize their platforms, misinformation thrives, with only a small fraction of viral content receiving community notes or corrections. Left-wing politics on social media is largely centred on calling out systemic issues, while right-wing politics often focuses on manufacturing outrage around so-called “left-wing” politics. Coupled with engagement farming, this dynamic creates unsafe digital environments, particularly in countries with weak or restrictive internet policies.

“The most important lesson learned is that we need the moderation of content and to combat the fake news on our structure and promote more education about the digital perspective, also by developing more active ways to bridge the digital gap we have when talking about vulnerable social groups and the different aspects of our internet society,” Silva added.

Towards Context-Aware Moderation

Queer people in Nigeria remain fearful of AI moderation and often resort to self-censorship. Most social media platforms are strict about the consequences of content rules violations, particularly those related to attempts to evade suspension. Most queer people are reluctant to create new accounts because Meta Platforms and X’s detection systems are strict. On the other hand, social media is often the only means by which queer Nigerians can express themselves and build a community they may lack in real life.

Queer bodies are inherently sexualized online due to structural biases. While they try to express themselves through censored or suggestive imagery, AI detectors frequently flag their posts as sexual content or adult nudity. Automated confidence scoring often marks such content as explicit, creating a backlog before it ever reaches human review.

Animashaun Azeez simplifies how the algorithm works for queer Nigerians using social media. He argues that algorithms are trained only within a global context and should instead be designed with country-specific considerations, particularly in African contexts, through context-aware moderation. This approach, he says, would also allow queer content creators to appeal decisions fairly by human transparency and accountability.

Azeez works with the queer organization Think Positive Live Positive Support Initiative and serves as a paralegal, helping bail out queer people who have been unjustly arrested because of their identity. In his view, his paralegal work and his digital advocacy are interconnected. While AI automation restricts queer people’s rights online, the law in real life provides clearer processes for securing their releases. The difference, he argues, is that on social media, the platforms control the process entirely.

Queer Nigerians are highly wary of algorithms because these platforms, with their vague rules, determine what qualifies under their interpretations. As a result, many choose to self-censor because the algorithm doesn’t prioritize queerness. On TikTok, the algorithm has been known to push queer content to heterosexual Nigerian audiences, exposing queer creators to a barrage of insults and homophobic toxicity.

Meta platforms perform better by pushing queer content primarily to users who already engage with it, whereas TikTok evaluates the “For You page” based on engagement and broader demographics. There is hardly any viral TikTok video by a Nigerian queer creator that has not attracted waves of “bullying” and “abuse,” leading to shrinking queer speech. A young queer person observing this violence against others inevitably becomes wary of expressing themselves online.

My survey indicates that respondents overwhelmingly perceive automated moderation as broadly harmful at the local level. Around 44% selected “all the above,” suggesting these systems simultaneously silence queer voices and reduce community visibility online.

When I joined X (formerly Twitter) in 2020 during the COVID-19 pandemic, it felt like a safe space that amplified queer voices, until Elon Musk took over and turned it into a right-wing platform. This perpetuation of digital inequity and exclusion contributes to psychological exhaustion among queer people. While most, if not all, social media platforms lack physical offices beyond their founding countries, the global AI guidelines set by bodies such as the United Nations and Human Rights Watch could play a crucial role in regulating these platforms, which serve as a global village for young minds.

As the survey showed, most queer Nigerian social media users do not appeal to the unjust decisions of platforms. Those who do, they either receive no response or have their appeals rejected.

In the United States and Europe, AI rules and regulations are clearly outlined in a content moderation framework, giving users awareness and recourse. There is no Africa-wide AI ethics blueprint or regional digital rights enforcement mechanism to strengthen the digital space. The European Union’s AI Act promotes transparency and outlines risk-mitigation measures, while the Digital Services Act mandates accountability for content moderation and algorithmic content recommendations. Additional policies address market power and data use. In the USA, there are federal frameworks, state-level laws, and general approaches to mitigating and addressing risks. There have been numerous lawsuits filed against social media platforms over content moderation. In contrast, Nigerian users must abide by the rules of the foreign platform in the absence of any national framework governing AI and moderation.

On the Nigerian social media space, especially X, disinformation and tribal bigotry thrive due to nonexistent regulatory structures. Anti-LGBTQIA bigotry expressed in local languages and Nigerian pidgin is difficult to report. Young minds are impressionable, including young LGBTQ+ minds. When I first joined social media, I was inundated with misogyny, homophobia, and all forms of bigotry from viral Nigerian influencers, before I found my community and began learning and unlearning. These localized harms shape young queer people, who often encounter these anti-queer posts before discovering their identity. Before the advent of generative AI, queer people turned to Google to understand their identity; now, AI tools simplify content in ways that do not prioritize the identities of the very people they claim to serve.

While including local queer moderators across different cultures might not be cost-effective, training AI models with peer-reviewed resources and consulting with queer organizations in these regions could help them better understand local queer contexts. Generative AI models, whether by themselves or integrated in social media platforms, should not overtly rely on top search results; instead, they should be more intentional about linking sources when providing answers, much like Wikipedia does. The consequence of limiting openly queer voices is evident in the proliferation of caricatured queer content by creators as punch-down mockery in place of upliftment or advocacy. This trend pushes queer rights backwards.

Furthermore, the algorithm pushing queer dating, love, and romance content to homophobic audiences on TikTok has led to doxxing and real-life harm toward such content creators. Maryam Yau, a lesbian in Northern Nigeria, was outed and jailed after a viral TikTok post about her partner. She was detained under the Northern sharia law that operates in Northern Nigeria and applies to 12 states.

Meta algorithms consistently boost Western queer love, yet rarely amplify the local queer expressions that appear daily on their platforms. These cumulative effects lead to queer people becoming afraid of their identities, being discouraged from sharing their experiences, and these end up shrinking queer spaces.

The survey asked respondents, “Do you believe global AI governance should involve queer voices from the Global South?” A majority of respondents (56.3%) strongly agree with the statement, while a further 28.1% agree, bringing total support to 84.4%. In contrast, 15.6% of respondents disagree, and none strongly disagree. These findings indicate a consensus among the majority of participants that queer voices from the Global South should be included in global AI governance discussions.

Data from this research survey also shows that queer people are most in need of legal protection for online speech. In an era of rapidly advancing AI, a governmental framework for AI regulation could help ensure its safety. Alternatively, robust global AI rules, grounded in human rights and championed by international organizations, could shape safer social media spaces for minorities in developing countries, especially in Nigeria.

SUPPORT US

We like bringing the stories that don’t get told to you. For that, we need your support. However small, we would appreciate it.