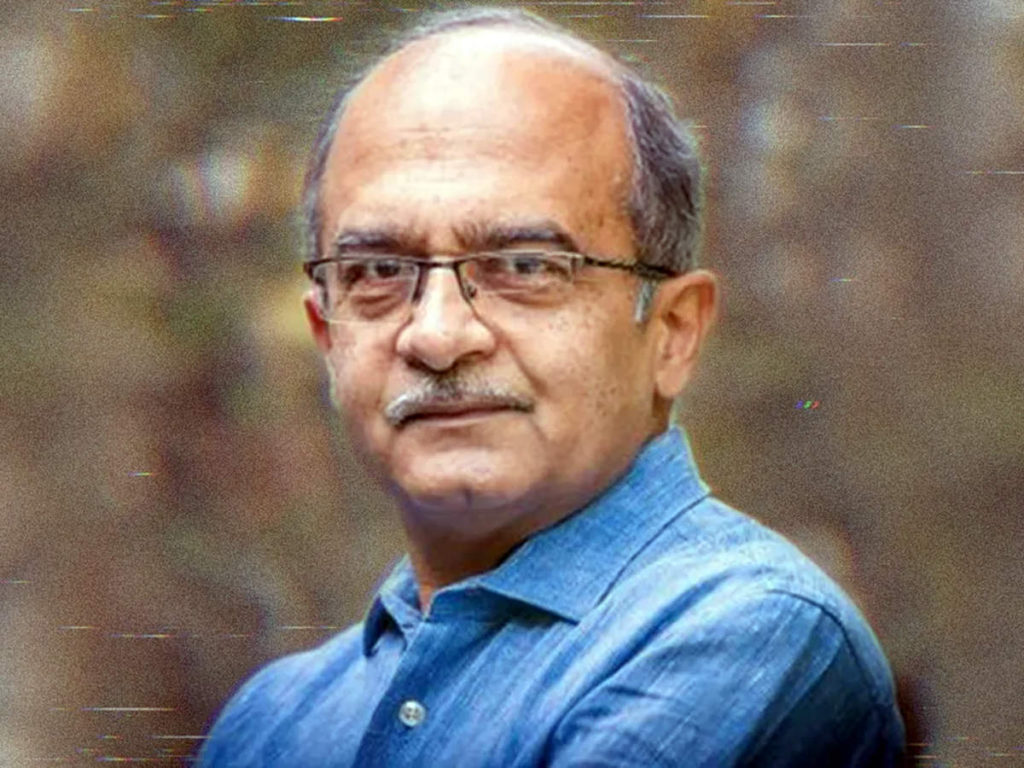

Modi’s DNA is not just of an autocrat or a communal fascist, but of a lumpen street thug — A conversation with Prashant Bhushan

Our second episode of War, No War—a Polis podcast series hosted by journalist Parvaiz Bukhari—features Indian civil rights activist and Supreme Court lawyer Prashant Bhushan. Bhushan is known for his public interest litigations and anti-corruption work. He is associated with various organisations including the Centre for Public Interest Litigation, People’s Union for Civil Liberties, and India chapter of Transparency International. He successfully challenged the grossly inadequate compensation provided to the victims of the horrible Bhopal gas tragedy and forced the Supreme Court in 1990 to reopen the criminal liability aspect in the case against the former Chairman of Union Carbide Corporation Warren Anderson. Bhushan was a part of the anti-dam movement Narmada Bacho Andolan and fought in the Supreme Court against the construction of Sardar Sarovar Dam, a case the movement lost while gaining rehabilitation orders for the affected people. He has also been one of the principal drivers behind a crucial campaign for judicial accountability and reforms in India. During his numerous legal crusades in the last three decades he has faced contempt charges from the Supreme Court twice.

Bhushan is known for his public interest litigations and anti-corruption work. He is associated with various organizations including the Centre for Public Interest Litigation, People's Union for Civil Liberties, and the India chapter of Transparency International. He successfully challenged the grossly inadequate compensation provided to the victims of the horrible Bhopal gas tragedy and forced the Supreme Court in 1990 to reopen the criminal liability aspect in the case against the former Chairman of Union Carbide Corporation Warren Anderson. Bhushan was a part of the anti-dam movement Narmada Bacho Andolan and fought in the Supreme Court against the construction of Sardar Sarovar Dam, a case the movement lost while gaining rehabilitation orders for the affected people. He has also been one of the principal drivers behind a crucial campaign for judicial accountability and reforms in India. During his numerous legal crusades in the last three decades, he has faced contempt charges from the Supreme Court twice.

Transcribed by Preetika Nanda.

The text is edited for style and clarity.

PARVAIZ BUKHARI: Hello and welcome again to the War, No War podcast series at The Polis Project. This is Parvaiz Bukhari and today I am delighted to be with Prashant Bhushan, one of India’s top lawyers at the Supreme Court in New Delhi. Prashant is known as someone of absolute integrity and many call him one of the most courageous practitioners of law in India. He has the unique distinction of consistently and courageously challenging power for the public interest, be it the Indian state, the political executive, big corporations, the judiciary, and even the Supreme Court and the chief justice of India, you name it.

Prashant does so by engaging with people on the ground, with public policy, and various popular public movements. His work, activism, and struggle always remind us of critical things important for the health of a democracy.

Thank you, Prashant, for making time for this conversation.

PARVAIZ BUKHARI: To begin with I want to ask about your view on India today. The political climate in India has transformed significantly in the recent years. A sort of fascism has been creeping into the Indian state and society in general. Looking at it from within the framework of law and the constitution of India, what animates you the most today?

Well, this is clearly the most serious assault on the constitution—on democracy, on the rule of law and indeed on civilization itself—that we have ever seen in this country and this has been unleashed in the last five years by this Modi government. It’s an assault on all our institutions created by the constitution or created to protect us against corruption or to ensure free and fair elections. We see an assault on the judiciary, the Election Commission, the Comptroller and Auditor General, the Central Vigilance Commission, the Lokpal, the CBI [Central Bureau of Investigation], the National Investigating Agency, the universities. Every institution in this country is being suborned by making it either lack independence and falling in line with the government when they are supposed to be independent, regulatory institutions. Or by making it subservient to the will of the RSS [Rashtrya Swayamsevak Sangh] by appointing people who are affiliated to the RSS to these institutions. And simultaneously you have this lynch mob which has been unleashed on the streets and even on the social media. So anybody who criticises the government or the prime minister, etc., is abused, is threatened on the social media, on the streets, everywhere. So, we have never ever seen this kind of assault on not just our democracy, not just on the constitution, but indeed on civilization itself.

Sounds very dire and dark indeed. India, of course, went through a period of emergency rule for 19 months way back in 1975, and many in the country today remind themselves of the hegemonic exercise of brute power by the then prime minister, Indira Gandhi. So, all these years later, why does Prime Minister Modi seem to be going the same way and evoke those memories? Has the steady expansion of the prime minister’s powers been permanently affected in India?

What we are seeing today is much worse than what we saw during the emergency. During the emergency there was certainly an assault on the right of liberty by imprisoning a lot of people. There was also an assault on press freedom because of press censorship. But other institutions in the country, civilized values… lynch mobs were not out on the streets. This kind of very vulgar, violent culture had not been created. This is something which has happened during the last five years in particular when Mr. Modi has come to power, and Mr. Modi has thereafter singularly taken control of the government as well as of the party, through Mr. Amit Shah of course. And it is really the culture of Modi and Amit Shah which we now find. Of course, the RSS on one hand. We have [an] assault on secularism, on Muslims, which is going on. And on the other hand, this unique gift of Mr. Modi and Amit Shah to this nation, which is to destroy all institutions to promote a culture of fake news, of abuses of violence, etc. This is a unique gift of the Modi-Shah duo.

A lot of what you are talking about also gets drowned in this new climate of nationalist outpouring that’s been almost engineered in India. Professor Gyan Prakash in his very close examination of the emergency period in his new book “The Emergency Chronicles” actually says that Indira Gandhi would never have imagined the power of usurpation that Modi has actually practiced. Would you agree?

Yes, absolutely. Absolutely. Mrs. Gandhi eventually ended the emergency after 19 months because she had… the basic DNA of Mrs. Gandhi was not of being a complete autocrat. Her basic DNA was democratic. So far as Mr. Modi is concerned, his basic DNA is not just of being an autocrat, not just of being a communal fascist, it’s the DNA of a lumpen street thug.

You began by talking about how this comprehensive nature of the assault on Indian institutions has been going on for some time. You have also been one of the central [figures] in the Campaign for Judicial Accountability. You talked about the assault on the judiciary. Since it began some three decades back, tell us about its principle elements and where it is directed. Has the campaign changed anything? Is there an institutional mechanism in India to deal with corruption in judiciary and to survive the kind of assault that you just spoke about?

The judiciary has, is, beset by all kinds of fundamental problems. In fact, if you ask how many people in this country are able to get justice through the judiciary, the honest answer would be hardly anybody, not even one per cent perhaps. And the reason is that 80 per cent people are left out or excluded from the judiciary because they can’t afford lawyers, without whom you can’t move the system. Secondly the system is so lethargic that most cases get bogged down for decades altogether in the courts and appeals. And even when they come to be decided, they are often decided wrongly because of incompetence or corruption. Now, corruption unfortunately is an issue which is particularly serious in the judiciary because of lack of accountability of the higher judiciary altogether.

You don’t have any mechanism by which people can complain against judges. The only thing you have is impeachment for which you need a hundred MPs of the Lok Sabha to sign the impeachment motion, which political parties are unwilling to sign unless two conditions are satisfied. One, you have documentary evidence of serious misconduct on the part of the judge and, second, it should have become a public scandal. Unless it becomes a public scandal, even when you go with documented evidence of misconduct, political parties will not sign the impeachment motion because of a fear of a judicial backlash against them and their members. Therefore, if a judge commits an act of sexual misconduct, it’s very difficult to even register an FIR against that because of this judgment that has been given in Veeraswami’s case.

If you say anything, if you publicly expose a judge for wrongdoing, you run the risk of contempt of court and even the Right to Information (RTI) Act so far as it relates to the judiciary has been effectively thwarted by the judiciary itself.

[In the] Right to Information Act, incidentally, you were instrumental in bringing [the] transparency law about. The judges don’t come in its ambit, do they?

No, they are, they certainly are supposed to be amenable to the Right to Information Act. But what they have done is that even when the Information Commission asks the judiciary to disclose information, a writ petition is filed by the judiciary itself in the High Court or the Supreme Court and the order of the Information Commission is stayed. So the judiciary is the least transparent institution in [the] country. It singularly enjoys this power of contempt, which is a kind of unbridled power. It’s the only institution where judges cannot be prosecuted without getting the permission of the chief justice of India. And it is the only institution where there is effectively no disciplinary control over these judges. Nobody has this disciplinary control, other than this process of impeachment, which is too cumbersome and impractical.

In that sense, it looks like the kind and nature of impunity which the Indian armed forces have under something like the Armed Forces Special Powers Act. The judiciary enjoys the same kind of impunity…

No, under the Armed Forces Special Powers Act, the government can permit prosecution. It’s another matter that the government does not usually do that. But, here, nobody can permit that prosecution unless the chief justice himself allows it and, unfortunately, we have seen that judges do behave like an “old boys club” to protect each other.

That’s even worse than what AFSPA does for the armed forces…

Yes. In many ways, it is [worse].

Could you give us a quick instance of when this impunity came to the fore in recent times?

We started seeing it from Ramaswami’s time. That was the first case of impeachment. Before that his father-in-law, Veeraswami, was sought to be prosecuted for corruption. The case came up to the Supreme Court in which they gave this judgment that judges cannot be prosecuted under the Prevention of Corruption Act unless you get prior sanction of the chief justice. They can’t even be investigated. You can’t even register an FIR against them.

But in Ramaswami’s case, we saw how difficult it is to get through an impeachment motion. That was one of those cases where there was a judge’s inquiry committee that held him guilty and yet the impeachment motion fell because the Congress opted out of voting and it couldn’t be passed by absolute majority in the Lok Sabha. Thereafter, we have successively seen it in the attempted impeachment of Justice Punshi, Justice Anand, and several other judges. But it’s virtually impossible to get it going.

Let me take you back a decade. You got into a lot of trouble over a statement you made about Kashmir about a referendum as a solution to the dispute. You were assaulted after that statement and a lot happened. What do you think that extreme sensitivity is about?

First, I think what I said was not properly understood or appreciated. The question that was asked was what should be the solution to Kashmir. And I had said that in my view it’s important to win the hearts and minds of the Kashmiri people, and one of the major reasons for their feeling alienated was human rights violations by the armed forces, and a major reason for that was the Armed Forces Special Powers Act, and therefore we need to first remove the Armed Forces Special Powers Act. If the Kashmiri people don’t want the [Indian] army to be there for their internal security [but] only for external security at the borders, then it should be withdrawn from internal security duty there. And I said that thereafter there should be a proper democratic government which works for the people. But if you can’t do that, if you are unable to win the hearts and minds of the Kashmiri people, then, perhaps, we should give them the option of choosing as to what they want. Would they want to become independent? Would they want to remain part of India? Whatever. So that choice of self-determination so far as Kashmir is concerned, if we are unable to win the hearts and minds of the people, what’s the harm in doing that? Because then people say “look, that would start happening for rest of the country, for many other states also.” But, there is a difference between Kashmir and other states. That’s why Kashmir was given a special status under the constitution, because there was a completely different historical context in which Kashmir had acceded to India. And, therefore, as a human rights activist I feel there would be nothing wrong or immoral… about [allowing] the people of Kashmir to decide their fate, if we are unable to win their hearts and minds. Of course, ideally Kashmir should remain part of India, should work within the Indian union and Indian democracy etc. But that should happen if we are able to win the hearts and minds of those people…

Listen to War, No War Episode 1

Is Kashmir under military occupation?

You are one of the very, very few people in India who would say this today particularly, and we’ve seen over the last many years that talking about Kashmir in its historical constitutional context has almost been criminalised. Not that it wasn’t so before the last five years, but where do you think that criminalisation has gone, because I’m surprised that you talk about Kashmir as clearly as you did, even today. A decade after you faced an assault for saying the same thing. Not many people say this today in India.

Yes, unfortunately, this kind of nationalism has been drummed in which “Kashmir toh humara abhinn ang hai and kisi bhi halat main Hindustan se alag nahi ho sakta wagera, wagera” (Kashmir is an integral part of India). That seems to be treating Kashmir as a mere piece of territory. But Kashmir is not territory. Kashmir is people. There are millions of people living in Kashmir. And to treat a state as mere territory which is to be kept as part of India even if the people there have seceded from India in their hearts and minds, that doesn’t make any sense to me. Of course Kashmir ideally should remain a part of India because India is a robust democracy or India should be robust democracy but for that we need to ensure that human rights violations don’t take place in Kashmir, for which the impunity granted to the armed forces through the Armed Forces Special Powers Act should go. We need to ensure that democracy functions properly there in Kashmir. Only then can we win their hearts and minds.

I would like to take you back to the issue of corruption particularly in the judiciary. Way back in 2009, if I’m correct, you claimed that half of the 16 former chief justices of India were corrupt. I guess you also faced charges of contempt of the apex court for saying it at that time. How is the situation now? Do you think the corruption in the Indian judiciary is really insidious?

Yes, unfortunately, though ten years have elapsed since I made that statement. And in these last ten years we have seen at least ten chief justices who have come. That figure of 50 per cent seems to have been constant. So, unfortunately, we have had a lot of corruption in the judiciary, specially at the apex. It’s very worrying because the judiciary is the most important regulatory institution in the country. It is what is supposed to guarantee the fundamental rights of the people. It is supposed to hold the executive and legislature in check to ensure that they don’t transgress the limits of their power and to ensure that they do their duty, specially the executive. And, therefore, if the judiciary collapses, if you have corruption in the judiciary, then it is easy for the executive to suborn the judiciary. And even the independence of the judiciary will not remain if the judges are corrupt because the government is able to use its agencies. And this is a unique contribution of the present government as well, that it’s able to use its agencies like the CBI, IB, Enforcement Directorate, Income Tax, etc to find out the evidence of corruption of judges and use that evidence to blackmail them into submission, which is what has happened to some extent in the past.

So you are saying what you said a decade back holds true today. Half the judiciary at the top could be corrupt.

Yes, unfortunately, that is the case.

And that’s irrespective of which political party rules… have there been any changes brought about in the appointment of judges at the top? Has that made any difference at all?

No, the change happened in 1993 or so when that judges case judgement was given where the power of appointment was taken away from the executive and appropriated by the judiciary. Now what that has done is that to some extent that has led to slightly more independent judges being appointed. But the corruption or the lack of accountability or nepotism etc has remained. So, it has not led to very substantial improvement in the quality of judges. Slight improvement in independence, but that’s about it.

Your being part of the campaign for judicial accountability, has it achieved anything in this direction so far. It’s also been a long running campaign.

All that it has done is that it has flagged the issue of the problems in the judiciary or problems of judicial accountability or the need for comprehensive judicial reforms. So that issue has just been flagged but, unfortunately, we have not been able to create a people’s movement large enough around this issue which is what would be needed to put pressure on the government or on the judiciary itself to bring about the judicial reforms that are required.

Do you think that can happen by bringing about public pressure? Why has that public pressure not been built?

To create a people’s movement requires a great deal of organising and I don’t have those organizational skills at a people’s level. Arvind had that, and he did do so.

Arvind Kejriwal…

Yes, for the Lokpal Movement. We need somebody with organisational skills at the ground level to be able to organise a nationwide people’s movement on the issue of judicial reforms. … It will require more people who are more adept at creating people’s movements to get more integrally involved in this campaign.

What do you think needs to urgently happen?

I think we need to organise around the people’s movement in this issue, because judicial reforms are certainly one of the most important problems that we need to tackle. Unless we reform the judiciary and make it a properly functional and effective instrument to deliver justice to the majority of our people, we would not be able to tackle many of the other problems that face us. Therefore it’s certainly one of the critical problems in the country. Because, unfortunately, it suits both the government as well as a judiciary to have a dysfunctional judiciary. So far the government is concerned they feel if the judiciary remains dysfunctional we will not be held accountable. For judges, arbitration has become a big industry for retiring judges and it’s flourishing only because the normal judiciary has collapsed. Therefore, people with money are forced to resort to arbitration for which they have to pay high fees to these retired judges who are appointed arbitrators and there are many judges who are making crores through arbitration. This [also] has made the judges complacent about what’s happening.

Sounds horrifying at many levels. Now if I can bring your attention to your public interest litigation work and your activism. You also believe in harnessing the power of the media and much of your work, if I am correct, also resides at the intersection between the courts, law, and media in India. Has it been possible for you to build media pressure on courts for aligning big policy to public interest?

Yes, I feel that one of the things that happens with public interest litigation is that it also gets some attention in the media and therefore many issues which are brought to courts through public interest litigation also get highlighted through the media. And sometimes that helps in building public opinion on those issues and I also find that judges also are more responsive to issues when there is a lot of public involvement or interest among the people on those issues.

Which principally happens through the media…

Yes, which principally happens through the media. Of course, today, that doesn’t necessarily mean the mainstream media but also means the portal media, social media, etc.

Another aspect of your work. You challenged the chief justice of India’s powers to list and allocate cases to different judges, drawing the roster as it is known, basically saying the chief justice of India should not be the master of the Supreme Court roster. How did the apex court respond to that?

Well, we felt that this power of being the master of the roster and being able to decide which case will be heard by which bench is a very important power through which you can affectively determine the outcome of every case. Because there are always judges who you know would decide in a particular way in a particular case. So, if that power has been misused or abused, as it has been in the past, then, again, the judiciary cannot function in a credible manner. Therefore, that power cannot reside in one person. [Otherwise], one chief justice effectively comes to control the entire Supreme Court and he is no longer the first among equals but virtually the dictator in the Supreme Court. So we felt that power should be exercised not by one person but a collegium of at least five senior judges and we had gone to court seeking that. Unfortunately, the Supreme Court didn’t agree with that…

What was the reason given for the denial of this demand?

They just said that traditionally it has been so and it will be very difficult to manage the courts otherwise.

So, it was all about keeping the tradition of impunity on rather than looking at changing the system?

Yes, in just continuing with the status quo of this conventional view that the chief justice is the master of roaster.

In recent years, one of the very high-octane cases, if I may say so, that you dealt with was the case of the mysterious death of a judge in the state of Maharashtra, Justice Brij Gopal Har Krishan Loya. Justice Loya was of course hearing a very important case at that time which involved, among other people, the president of the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party, Amit Shah. Where did that case end?

We were seeking an independent investigation into his death because there were many things which suggested that he did not die in the manner in which he was said to have died, which is by a heart attack or a heart problem. In fact, some of the leading cardiologists whom I had consulted after looking at his papers felt that even his post-mortem report felt that he was unlikely to have died due to a heart attack. So there were many things which raised a lot of suspicion about the manner of his death and, therefore, we felt it needed an independent investigation. Unfortunately, that was another case in which the court did not agree. Even though the state of Maharashtra had not even filed an affidavit but just an unattested note—which wasn’t even shared with us—about some informal investigation that they were supposed to have done. On the basis of that note, the Supreme Court disposed of that case saying there was no need for any investigation.

That sounds arbitrary. Can you tell us something about the case that Justice Loya was hearing, and why his death and that case makes it that much more important that it went to the Supreme Court and was dealt with the way it was?

It was the case of the Sohrabuddin, Kauser Bi, and Prajapati encounter killings, in which the CBI had filed a very detailed 10,000-page chargesheet against several police officers and the then [Gujarat] home minister, Mr Amit Shah. [The CBI] had annexed a lot of evidence of Mr Amit Shah’s phone calls to these police officers around the time of the murder… some very large number of unusual calls around that time. Unfortunately, in that case, everybody one after another has been discharged. Most of the senior officers have been discharged. Mr Amit Shah was the first person to be discharged, and he was discharged by the successor of Judge Loya in just one hearing.

So, would you say the mysterious death of Justice Loya will never be investigated now?

No, I suppose it can be investigated by any future government but they would have to find some way of getting around this Supreme Court judgment.

Right. Again, back to the Supreme Court. More recently a former employee of the Supreme Court who worked at the private office of the incumbent chief justice, Justice Ranjan Gogoi, accused him of sexual harassment. What do you think of the how the complaint was handled by the Supreme Court under Justice Gogoi?

It’s been handled pretty badly. Firstly, on the very day that the complaint came out in the public domain, a special hearing of a bench on a holiday was held with great alacrity by the chief justice who himself sat in that bench and in which they pronounced that the woman as being some kind of criminal and that the allegations were the part of some conspiracy. [It] was totally unfair and unbecoming, in the absence of this lady, for the chief justice to pronounce himself to be innocent and a victim of some conspiracy by constituting a special bench himself on a holiday. It was very, very unbecoming and violative of all principles of judicial conduct, natural justice, and fair play.

After that, there was all this business about conspiracy which was spun out on the basis of some affidavit given out by one young lawyer called Utsav Bains, where he first in his Facebook post said that this was a conspiracy by retired judges and politicians. Thereafter in his affidavit he [mentioned] some corporate figures, Naresh Goyal of Jet Airways, Dawood Ibrahim, some former court employees… all kinds of things were trotted out. And on the basis of that, the Supreme Court has ordered an investigation by a retired Supreme Court judge.

Thereafter, the court, or the chief justice, constituted an in-house committee of three judges where one of the judges thereafter recused himself. Finally [the committee] came to be of two women judges and one senior-most puny judge after the chief justice, Justice Bobde. They held in-camera hearings and called this woman, who said “look, I want at least my lawyer or some support person to be present. Please also record the proceedings of the committee so that there is no dispute about what transpired and also tell me what is the procedure that you want to adopt in this so that I know what I can do or what I can’t do etc etc.” Unfortunately, none of these demands, which were perfectly reasonable on part of this woman, were accepted. As a result, after two or three hearings, the woman walked out and said there was no point in her participating in the hearings anymore. Afterwards they have given some ex-party report in which they have apparently said that they didn’t find any evidence of the chief justice being involved and they found her allegations not to be made out. Then the woman asked for a copy of this report [but that too has] not been given to her. This has led to a lot of outrage and protests, especially amongst women’s groups across the country, [calling] the manner in which the court and the in-house committee has handled [the case] most unfair and unjust.

What should have ideally happened? How should have this compliant been ideally treated?

The lady had written to all the judges of the Supreme Court saying that an external committee of a few retired judges be set up, and that’s what should have been done. Because the colleagues of the chief justice would find it very difficult and embarrassing to act in a very independent manner in a situation where the allegations are against their own chief justice. So, there should have been an external committee of some retired judges or some very senior civil society persons from outside.

So now that it’s over, what do you think this case does for the judiciary and the public perception of the court’s ability to deliver justice, because this was a complaint of a very serious nature against no less than the chief justice of the Supreme Court.

Yes, it has dealt a very serious blow to the image of the judiciary. The image of the judiciary has never been as low as it is today, partly as a result of this case, and I think the judges, specially the judges of the Supreme Court, should be taking stock of what it has done to the image of the court.

I want to take you back to your younger years as a lawyer. You cut your teeth in the case against the construction of the Narmada Dam. You were very intimately involved with people on the ground in that movement in central India. Was that case against the construction of the dam itself or for justice for the people it displaced? What happened finally?

No, it was also about the construction of the dam. There were three broad issues raised. One was the issue of displacement of the people, that they were not being rehabilitated in accordance with the award of the Narmada Water Dispute Tribunal, which said they be rehabilitated by giving them land for land and at least five acres of land to each family and so on. The second issue was that the project was going ahead without considering the environmental impacts; environmental impact studies were not done. And the third issue was that the cost-benefit calculations had not been done [regarding] various alternatives of providing irrigation other than this dam.

Now one of the judges in that judgment, Justice Bharucha, felt that it can’t go ahead; it’s wrong for it to be taken ahead without environmental impact assessment. So he said that the project should stop and these studies should be done and then only any clearance could be given. But the other two judges, the majority, felt that it could go on and these studies could be done simultaneously with the construction of the dam. They [also] said that rehabilitation should be done before displacement. Unfortunately, thereafter, people have been displaced without any rehabilitation. Majority of them have not been given land for land because most of the people were the oustees of Madhya Pradesh and Madhya Pradesh was unable to give them any land. As a result they have been largely left high and dry and the Supreme Court has not done much to even ensure that that part of the judgment were enforced.

So, so many years later, what do you think the Supreme Court decision in that case means today, that the people have been left without justice?

That judgment was unfortunate on two counts, the judgment and what happened thereafter. Unfortunate because it said that the construction can go ahead without an environmental impact assessment. It was good that they said that rehabilitation must be done before displacement. Unfortunately that good part of the judgment was not enforced. Subsequently it became clear that oustees of Madhya Pradesh were not being given land for land and despite that they didn’t stop the construction of the dam. As a result it was allowed to become a fate accompli. And…

And the Supreme Court could not do anything to have its own judgment about rehabilitation before displacement enforced?

Unfortunately they did not do enough to get its judgment enforced.

Where do you think that kind of approach comes from? The Supreme Court delivers a judgment, a part of which, as you said, was very good—about the rehabilitation of displaced people—and it doesn’t happen, and nobody follows it up. What does that say about the credibility of the whole system, including the Supreme Court?

It’s not very flattering for the Supreme Court. What I have been seeing repeatedly over the years is when there are powerful interests—government and powerful corporates—on one side and just poor, weak people on the other side, usually the powerful vested interests win even in the courts. By and large that’s been the case. That happens for many reasons. It happens sometimes because of subconscious bias in the minds of the judges. Sometimes [due to] a lack of adequate sensitivity to the rights of the people. Sometimes it also happens if judges come to be influenced directly or indirectly by the government or by corporate interests.

So that is again a question of corruption in the judiciary. Now, about displacement, there is also this question of Adivasis, the tribal people in India, who live in forests rich in mineral reserves. There is also a Maoist armed movement against the Indian state ongoing for many years in some of these areas. And recently we have seen this order, correct me if I am wrong, which seeks the displacement of millions of tribal people from their land. Is this congruous with India being a constitutional republic?

Yes, it’s a bit unfortunate that the court had… [sighs]. This is not the first time that this has happened. And even earlier, before the Forests Rights Act came, there have been orders of removing people from the forests, tribals who have been living in the forests for generations, on the ground of environmental protection. So we have seen this happening earlier also and even after the Forests Rights Act has come… it’s well known that forests rights under the Act have not yet been properly implemented in most or many states. And, therefore, forest-dwelling people who are to be given ownership of those lands have not been given [ownership] and yet the courts said that those who have not been given [ownership] should be treated as encroachers, without ensuring that the entire process of the Forests Rights Act was followed through properly. Without hearing the tribals themselves, they passed this order. Ultimately, of course, because of government pressure, the order had to be stayed and the matter is still pending in the courts.

We talked about corruption in the government, corporate corruption, and corruption in the judiciary. Of course, this story of corruption in India is long. There was the Bofors Scam, the purchase of artillery guns by the Congress government decades ago. You were a young lawyer then and now, decades later, we have the Rafale fighter jets purchase from a French company. You wrote a book about Bofors then. You have also been, I believe, at the forefront of the alleged corruption in the Rafale deal. What do the Bofors and Rafale defence deals reveal? It spans 30 years…

It is well known that there is a lot of corruption in defence deals… because it is easy to take kickbacks from foreign companies and foreign accounts etc, which is what happened in Bofors. Though the Bofors was a relatively small scam in terms of size. It was just a four percent commission scam in a Rs 1,600-crore deal, which meant 64 crores of commissions being paid into the accounts of different people, including one Quattrochi, the Hindujas account, and so on. However, Rafale is a defence scam of a different order altogether. In this particular scam, it is not just the size—because it is a Rs 60,000-crore deal in which half of that Rs 60,000 crores is to be given by way of offset contracts and most of it is supposed to go to Anil Ambani’s joint venture with Dassault…

The company that supplies the Rafale jets…

Yes. Anil Ambani had no business of being involved in this because he has no experience, his track record is very poor, his companies were all in debt… was being prosecuted in the 2G scam and so on. This deal was struck in violation of all rules and procedures by the prime minister himself by scrapping the earlier proposed contract of 126 aircraft, and then unilaterally deciding to buy only 36 aircraft, jettison transfer of technology and Make in India through Hindustan Aeronautics Limited, and also simultaneously increase the price of the aircrafts.

Now the airforce needed at least 126 planes, that’s why the first deal was going through, which was started by the UPA. It had gone through the entire process, it was more than 95 per cent complete and suddenly it was jettisoned, and you got just 36 aircrafts, and all in ready and fly condition… you didn’t get, I mean, you contracted to buy. Now, this meant that you have left the airforce high and dry. And the reason why you changed it to 36 is because you needed to give commissions to Ambani, for which you needed to increase the price of the aircraft. These commissions are being given through offset contracts. And if you increase the price, you didn’t have the money to purchase 126 [aircraft]. So, you thought alright let me just purchase 36. I’ll increase the price of these 36 per aircraft. I will give 50 per cent offset contracts to Ambani and to Dassault etc and that’s how the scam was taken through. So, in this particular scam it is not merely that about Rs 30,000 crores would be going by way of offset contracts to companies who can’t do anything. It is also that you have left the airforce high and dry, and thereby you have compromised our national security, because the airforce needed 126 aircrafts.

So, what do you think is at the core of it? I mean corruption is almost always, ultimately always ends up being about money and huge sums of money. So, is it about funding a political party in India, or is it about electoral funding in India. Where do you trace it finally?

In my Bofors book I had written that a lot of people had said at that time that those commissions must have gone to the Congress party. So, these commissions etc go to accounts which are usually foreign accounts and these foreign accounts remain under the control of some individuals, whether they choose to give to their party is up to them. So, ultimately, it’s money going to certain individuals who are the key people who decide those contracts. In this case, it’s possible that some of the kickbacks have been given through electoral bonds. You see this government, the BJP government, introduced these electoral bonds, which is a non-transparent way of funding political parties and they also amended the Foreign Contribution Regulation Act to allow foreign funding of political parties with the result that if a company like Dassault, which got the Rafale contract, or Anil Ambani, wants to give kickbacks to the BJP… it can do [so] anonymously through electoral bonds. So some of it of course would go to the political party now through electoral bonds, earlier through cash, etc. But a lot of it would remain as funds under the control of the persons who decided this deal, namely Mr. Modi or somebody like that.

So, if these reports can be believed, the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party is now the perhaps the richest political party in the world. Do you think these deals and these scams have a role in making a political party as rich as the Bharatiya Janata Party today is?

Of course, of course, if you see the kind of favours the [likes] of Adani, Ambani, and such corporates have been given or people like Nirav Modi, Mehul Choksi, Nitin Sandesara, Sterling Biotech, how they have been allowed to loot our banks and flee the country. So obvious that they must have given some consideration to the ruling dispensation, that’s how they get their money.

Of course, these kinds of things run through regimes with opposing political ideologies ruling at different times in India. What do you think can put a break to it because it seems to have nothing to do with any particular ideology?

Yeah, so on the one hand we needed robust anti-corruption institutions, independent and robust. Unfortunately, they have destroyed all of them. Lok Pal was not appointed for almost five years. At the last moment, they have appointed people without any transparency, without involving the leader of the opposition, etc. And they have appointed pretty weak people. They have destroyed the Central Vigilance Commission by appointing people who were involved in protecting the prime minister in that Birla Sahara case, and so on. They have destroyed the CBI, they removed the director who was trying to be independent, Alok Verma, he was removed in a midnight coup and a very underserving person with a bad track record was brought in as the acting director. So, they have destroyed all the anti-corruption institutions. They need to be rebuilt, made robust, and independent. Simultaneously they have also amended the Prevention of Corruption Act… To say that no corruption investigation can be done except with the permission of the government means that no corruption investigation can take place, and they have not even notified the whistle-blower law. The law was passed but it has not been notified for the last five years.

Tell me about this law?

This law said that anybody who blows the whistle on government corruption can go to the Central Vigilance Commission which can investigate the matter through any agency which can also protect this whistleblower and so on. But that just remains on paper, it has not been notified. It just said it will come into force on such date if the government notifies. And for five years that notification has not been made.

Why do you think that it’s so?

That’s because this government didn’t want any anti-corruption law, or any law which encourages whistleblowers to blow the whistle on government corruption.

You were also part of a big anti-corruption movement a few years back that actually also birthed a new political party and you became a part of it—the Aam Aadmi Party (Common Man’s Party) and then you quit it. How do you continue working in this existing system where corruption is so deep rooted and widespread? You believe the institutional superstructure that runs India is so compromised by corruption, and how do you stay, how do you not become a cynic? You still engage with the political parties, you still engage with the same system.

Being a cynic means to just give up and retire. That’s no longer an option, that’s not an option for any of us really, because that means you are allowing the country to just go to the dogs by giving up the fight. You have to fight to do whatever you can at your level to improve the system, to blow the whistle, to expose what’s going on, to educate and inform the people about what’s going on and what needs to be done to reform the systems. So, I try and keep doing that whether it is through public interest litigations or through the judiciary or through my involvement with various movements. I still try and do whatever I can and if there are a lot of people who are doing these things… but more people need to get involved in public issues and public affairs in order to see that this country is moving in the right direction.

From this conversation, I also gathered that the space for that kind of work may be shrinking and right at the beginning you talked about the unprecedented assault on the institutions of India that have been the strength of this country. Keeping all that we just talked about in mind, do you think India can survive as a constitutional republic given the pace at which the space for the work that you and your colleagues have been involved in for decades has been shrinking?

Well, I think it will require a lot of work and a lot of effort to make our republic survive. We are trying to make that effort. I am hopeful that we will breast the first hurdle, which is to get this government, the Modi government, out. I believe we are at that threshold and we will see this government out in another two weeks. After that there is a huge task of rebuilding the institutions, reforming various laws, and just generally trying to remove the poison that has been inserted in our society and in our polity in the last five years. It will take a lot of work to do that cleansing.

You think that is possible, it is reversible?

I think it is possible, it’s going to be difficult, but it will certainly require a lot of effort on the part of a lot of people. Recently in the run-up to the elections, one has been finding that a lot of people have been engaged in that work as they realise that the republic itself was at stake. Lot of people have tried to intervene in these elections in order to save it from another five years of Modi. Hopefully, those people will continue to engage even after this Modi government goes.

Prashant Bhushan, thank you very much for this very very illuminating conversation. Thank you.

Thank you.

Parvaiz Bukhari is a journalist based in Srinagar, Indian-administered Kashmir. He is on Twitter @parvaizbukhari.

SUPPORT US

We like bringing the stories that don’t get told to you. For that, we need your support. However small, we would appreciate it.

Related Posts

- Conversations

Modi’s DNA is not just of an autocrat or a communal fascist, but of a lumpen street thug — A conversation with Prashant Bhushan