Dadra and Nagar Haveli, August 1954—a unit of revolutionaries was marching to Khanvel village. Led by Comrade Narayan Palekar, the group consisted of masses from India’s western coast: the Konkani people of Goa, the Marathi people of Mumbai, and the Warli people of Surangi. Devoid of any weapons for self-defence, they marched with their heads held high, shielded by nothing but the unwavering call for liberation.

It was a mere seven years since India had received independence from British rule in 1947. Still, the country was far from liberated. Regions like Goa, Dadra-Nagar Haveli, and Diu-Daman were under the fascist Salazar regime, still largely ignored by the rest of the nation. A resourceful communist, Palekar hailed from Goa, but his objective wasn’t limited to freeing his hometown, even though the task started there. It extended to freeing every part of the country still under Portuguese rule first, and the systemic evils of capitalism and imperialism next.

Suddenly, a jeep screeched over. Two armed figures stepped out. It was Prabhakar Sinari and Prabhakar Vaidya from the Azad Gomantak Dal. Palekar’s shoulders relaxed upon seeing the two familiar Goan fighters; after all, he was acquainted with one of their members, Vishwanath Lawande. But after a moment of careful consideration, it dawned on him that the two weren’t there to extend support—they had arrived to counter their revolution.

Chaos was unleashed upon the troupe. Palekar, along with his comrade Dr. Sawant, was dragged into the jeep, hands tied. The vehicle headed off to an unknown destination. When it finally halted, they saw a new figure emerging before them. It was Vishnu Bhople from the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), an axe in one hand, ready to strike at his targets. Palekar screamed for help, and while he narrowly escaped the attack, a loud lathi blow from someone else landed on his head, leading to a severe injury.

While Palekar was eventually nursed back to good health, the day’s happenings presented a crucial revelation: this was a ploy orchestrated by the RSS, a Hindu nationalist political unit, in collaboration with the Azad Gomantak Dal, a religiously motivated anti-colonial Goan group that ran on similar Hindutva ideology. This scheme was constructed to curb the efforts of communist parties; a direct result of the growing wave of Red Scare in the country, led by religious outfits and the Government of India, who feared threats to national sovereignty, thanks to the communist-led Telangana Rebellion (1946-1951).

The common objective of freeing India from a foreign fascist rule wasn’t enough for the differing political units to look past their prejudices. Palekar—one of the founders and leaders of the Goan People’s Party, an atheistic anti-colonial group built on Marxist ideals—had become the latest target of a vindictive attack.

Goa and communism are often not uttered in the same breath. The iconic red flag bearing the hammer and sickle is commonly associated with the states of West Bengal and Kerala, thanks to their long Marxist history. But while looking for regional Konkani publications for a college assignment, I stumbled upon the weekly Romi-Konkani newspaper Vauraddeancho Ixtt, which literally translates to “Workers’ Friend.”

The name enthralled me. As a Marxist hailing from a Konkani-speaking family, the thought of an unheard-of worker-centric publication in my native place was fascinating.

But the more I read about the paper, the more I realized that it wasn’t supposed to be a Marxist opuscule but was, in fact, created to shield the religious working class of Goa from the “growing communist propaganda” in the state. “What communist propaganda?” I wondered, and thus began my journey into the rabbit hole that is Goa’s hidden communist surge.

A Brief Religious History of Goa, and the Formation of the Goan People’s Party

Goa has had a complex religious history spanning several centuries. Popular media that identify Portuguese travellers as the first settler-colonialists in the land fail to excavate the rest of its extensive history. In his 2023 book Ajeeb Goa’s Gajab Politics, author Sandesh Prabhudesai points out, “[t]he history of Goa does not begin with the Portuguese conquest of Goa in 1510. Rather, it ends with the end of Portuguese colonization, just 60 years ago.”

He goes on to debunk the common misconception of Gaud Saraswat Brahmins being the original inhabitants of the region, thus proving that the land had, in fact, been doubly colonised—initially by the Brahmins, later by the Portuguese.

The indigenous people of Goa included tribes such as the Gowdas, Kunbis, and Dhangars, often agriculturists and fisherfolk by profession, who practised their own distinct faiths. Somewhere between 1650 and 700 BCE, the arrival of Gaud Saraswat Brahmins in the region also marked the induction of Brahminism in the land; ultimately, the indigenous population was shelved into the lowest tiers of the caste hierarchy.

The arrival of Portuguese general Afonso de Albuquerque in 1510 signalled the start of Portuguese colonialism in the region. While Christianity had existed in India before the arrival of Portuguese settlers, it was under this new regime that Goan locals were vigorously mass converted. The Church was at the centre of this evangelist equation.

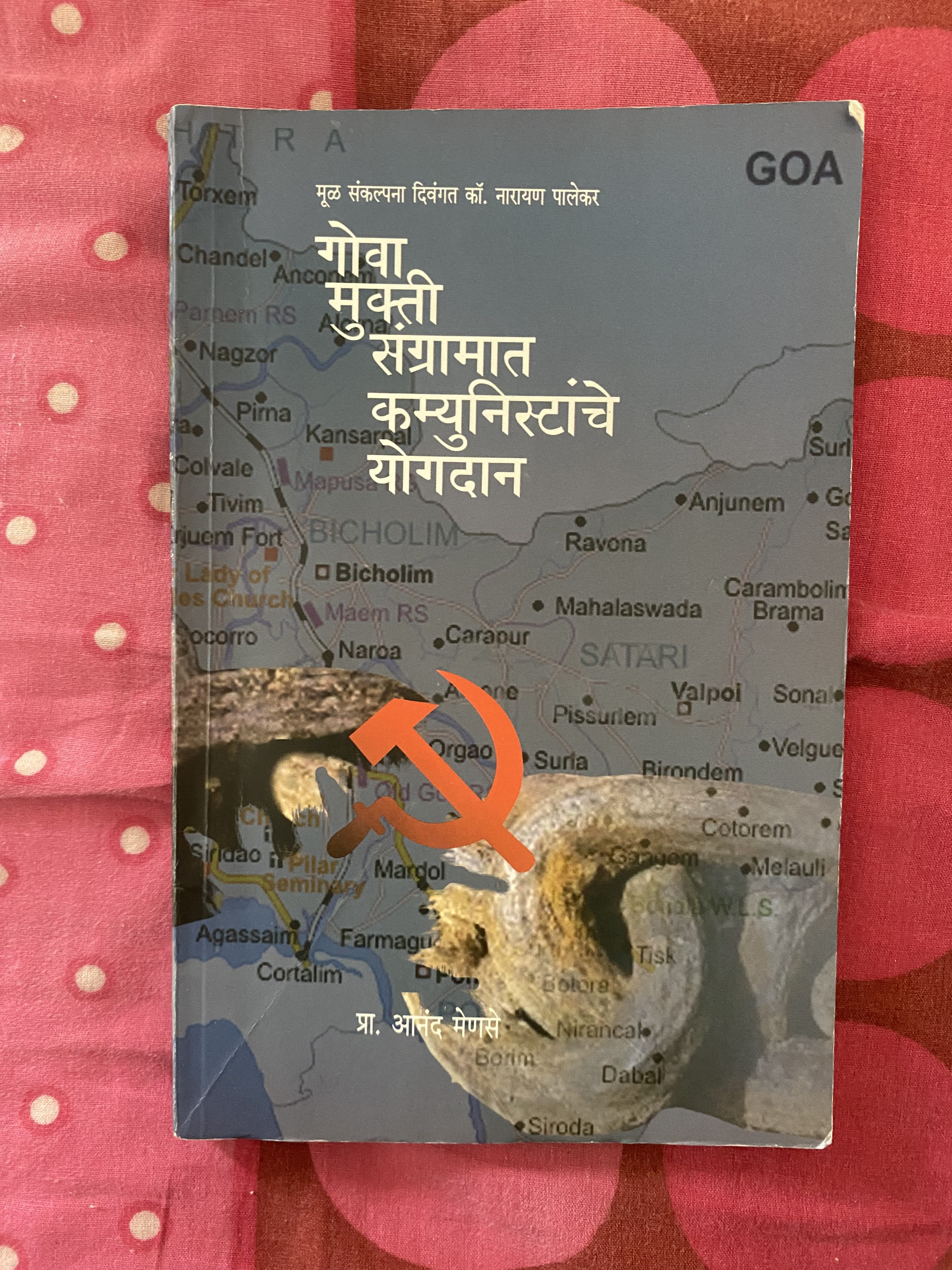

It was in this tense religious climate, from the late 1900s to the early 1910s, that people started seeking out higher education. Male students from well-to-do families would be encouraged to pursue higher education in cities like Mumbai and Belgaum—and if possible, abroad—which exposed them to an entirely unexplored treasure trove of knowledge. Professor Anand Mense explains in his 2011 book Goa Mukti Sangramat Communistanche Yogdaan (The Contribution of Communists in Goa’s Liberation Struggle) that it was this pursuit of higher education in larger urban centres outside Goa that sparked revolution among its youth.

There are several instances of this. Damodar Dharmananda Kosambi, the torch-bearer for Marxist historians in India, hailed from a Goan Konkani family and developed an interest in Marxism after accompanying his father to the United States and enrolling at Harvard University. Tristao de Braganza Cunha, the pioneer of Goa’s liberation struggle, was introduced to Marxist thought while pursuing higher education in Paris in 1912, after being greatly influenced by the Paris Commune.

The cause of Goa’s liberation was further taken up by the Portuguese Communist Party in 1921, which routinely called for the removal of the Portuguese empire in its publication Avante!.

Goa’s fledgling freedom struggle came to a standstill after António de Oliveira Salazar became Portugal’s Prime Minister in 1932. The oppressive Portuguese colonialism had now turned into a rigid fascist regime. Civil liberties were at stake. It had become imperative to take immediate action. It was under these drastic circumstances that Goa’s first proper communist movement unfolded.

In Mumbai, a new wave of progressive Goan student-youth, which flatly refused to be tied down by religion, had also decided to start their own communist unit. They aimed for the complete liberation of their motherland from both colonialism and religious dogma. In 1948, the ambitious Goan People’s Party, or GPP for short, was formed, helmed by General Secretary George Vaz and Secretary Narayan Palekar.

The GPP had several influences across the board, including the Paris Commune and the Soviet Union. Furthermore, it was modeled on the ideas of not only Marx and Lenin, but also political figures close to home like M. N. Roy and T. B. Cunha. The party operated mainly from Mumbai but also received support from like-minded political units in neighbouring cities like Pune and Belgaum.

The Ambiguity of Decolonial Political Ideology: Hindutva, Anti-Colonialism, and Communism

The ambiguity of political ideology in the party’s name can be attributed to the cancerous growth of the Red Scare across India. Any leftist party with the word “communist” in its name was automatically exposed to heightened risks. Outside the Portuguese and Indian states, communists in Goa attracted disdain from religious organizations, including Clerical and Hindutva groups. The Church has historically despised communists; the same can be reflected in Goa’s pre-independence Catholic mass media. One such example is Vauraddeancho Ixtt, the Goan periodical published by the Society of Pilar, a Roman Catholic society for men.

In a phone interview, Father Peter Francis, the manager of the publication, talked about how pre-independence periodicals/papers could not publish anything against the Portuguese government, as mass and broadcast media like newspapers were largely controlled and censored. “The punishment for speaking against the Portuguese government was a decree for withholding the publication for 90 days,” he mentioned, elaborating on how this particular “anti-communist” stance was a response to the GPP’s open atheism. The endless tug-of-war between Catholics and communists formed the baseline of Goa’s redundant political struggle.

“My personal reading is that the misreading of a selectively truncated half-quote of Marx—opium of the people—led to a lot of misunderstanding between religion and the Left,” observed journalist Frederick Noronha, who is based in Saligão, Goa. “The Left also mishandled the issue, and continues to go by what its critics say, rather than what Marx meant. To my mind, a more harmonious reading between religion and the Left can be seen in the growth of Liberation Theology in Latin America—which also made its way to Sri Lanka, and to a lesser extent to Goa in the 1970s and 1980s—as well as books like Fidel on Religion.”

Besides Catholicism, the 1940s were also the time when a fresh wave of Hindu nationalism was brewing throughout British India and then the newly formed Indian state. Moreover, the recent success of the Telangana Rebellion (1946-1951)—an armed peasant uprising against feudal exploitation and the Nizam of Hyderabad’s oppressive rule, led by the Communist Party of India—was seen as a threat by the erstwhile authorities, leading them to cement a strong sense of anti-communist attitude in the minds of the Indian middle class. This anti-communist attitude was also usually what led to in-fighting between political groups on either side of the spectrum, building towards the same end: decolonizing.

But decolonizing what exactly? The GPP had a broader goal in mind; the Azad Gomantak Dal (AGD), on the other hand, navigated the idea with the myopic perspective of eradicating the “foreign” religion as a remnant of colonialism.

“[The ideology of] AGD is a mix of anti-colonialism together with some degree of Hindutva,” explained Noronha. “Interestingly, the anti-Portuguese campaign fit in rather well in the Hindutva worldview: foreign rulers, religious bigotry, destroying native faiths, and such. So it needs a rather different reading from the experiences of the rest of India. Plus, it came a decade and a half later, after Gandhi’s assassination [in 1948], when groups like the RSS got enough time to rethink their beliefs, and the implications of the same.”

“Portugal was conservative,” Noronha continued. “In the early 1900s, Republican thought took hold in Portugal. But this also led to a big rise of the Left as an oppositional force in the 20th century. This can be seen from former Portuguese colonies such as Angola, Mozambique, and East Timor, where the history of the Left has been sometimes complex and complicated, but also influential.”

It’s hard to put a finger on Goa’s religious mosaic. My recent visit to my native place in Ponda, a Hindu-majority town, reminded me of all the times I had come here as a kid, amused by the numerous religious trinkets that the region is eternally brimming with. In most public places, figurines of Jesus and Mother Mary are worshipped alongside portraits of Manguesh and Shantadurga (regional variants of Hindu deities). I recall seeing objects of both Christian and Hindu faith placed in a synchronous arrangement in an inter-city bus; a miniature Cross placed neatly alongside a miniature idol of Ganesha.

It appears as a rosy feel-good picture of textbook secularism on the outside, but it does not take long to discover how this quasi-religious façade has unraveled in Goa’s morbid communal politics. “Goa is not a relatively secular region,” Noronha asserted. “That is deceptive. That Goa has had a form of soft Hindutva in power for much of the 1960s and 1970s is a well-kept secret. The Opposition then was also largely Catholic-supported. Even later, Congress politics reflected this. Since 2012, the BJP has been doing just about what it pleases, and most folks here tend to get easily polarized.”

It’s not hard to see why the GPP endorsed the complete abolition of religion.

Noronha differs, however. “Because of the hard line that the Left took on religion—again, a misreading of Marx—I think most serious Leftists would not be able to follow any religion, in conscience,” he said. “It is also true that the Church and Hindu society were rather conservative in Goa, which is why many of those fighting the Portuguese State also moved away from their religion, especially Catholicism, as Church and State were seen as closely interconnected in those times.”

Mass Media and the GPP’s Neglect of Caste Intersectionality

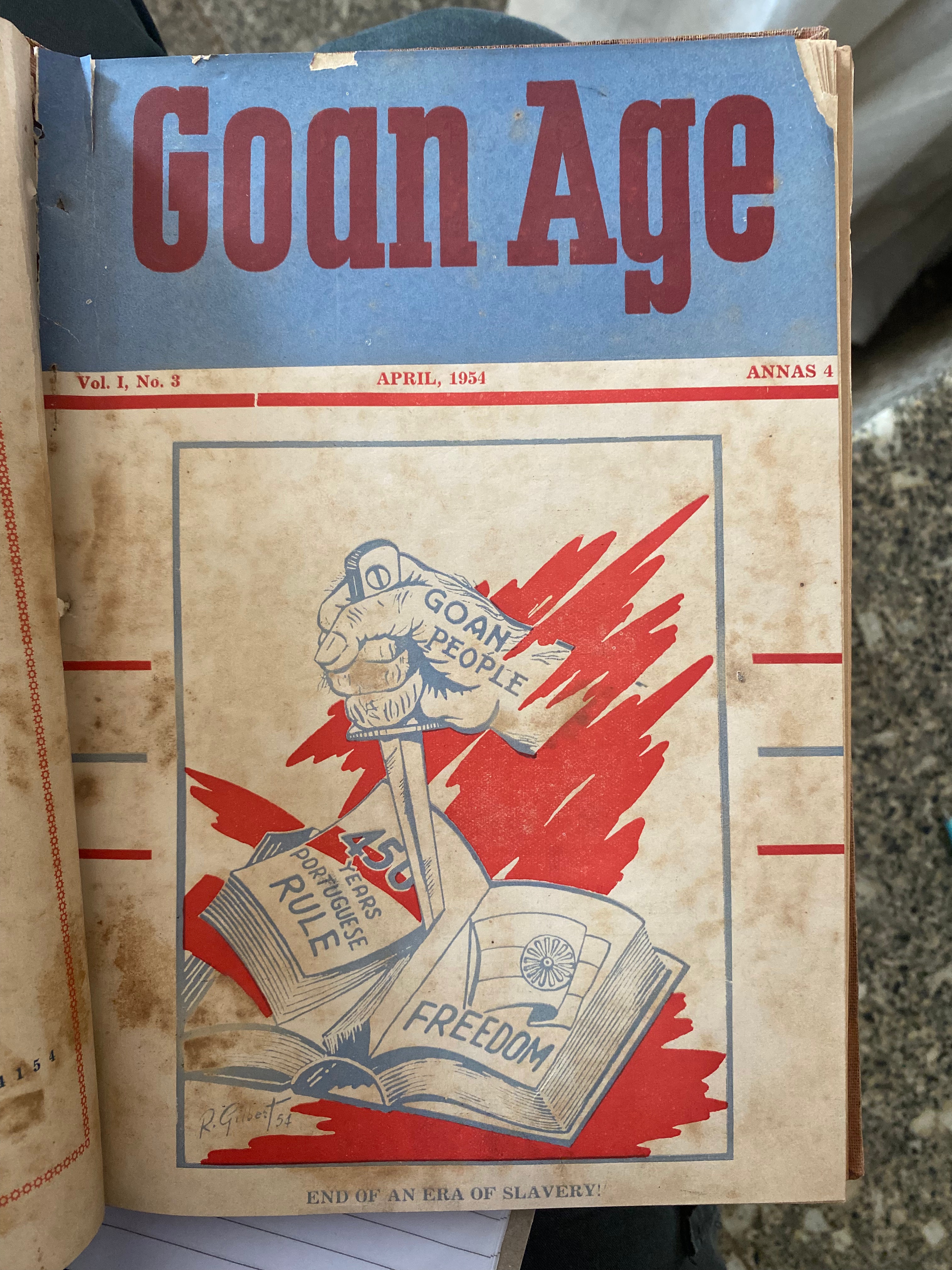

Mass media played a key role in the GPP’s curriculum. Even though Portuguese print media hogged the most space among Goan locals, resistant publications distributed by the GPP were tacitly getting the work of decolonization done in neighbouring regions. Goan Age, the GPP’s primary print organ, was launched shortly after their formation in 1948, with Gerald Pereira serving as the editor.

The publication featured essays, thought pieces, columns, op-eds, and illustrations condemning Portugal’s regime, as well as obituaries of martyrs fallen for the liberatory cause. The articles were written in both English and Romi-Konkani by several party members, writers, and scholars, including Pereira, Palekar, Berta M. Braganza, Dr. George D’Silva, and Victor Gonsalves. Correspondents from Japan and Portugal, who were sympathetic to the effort, were also occasionally featured.

I visited Mrs. Lara Pereira-Naik, Gerald Pereira’s daughter. Sitting in Panaji’s reputed Central Library, we engaged in an informative conversation about her late father’s involvement in the struggle, his views on religion, and his role in workers’ movements. “The GPP was not bothered about religion,” she narrated. “In fact, my father himself was against religion. The GPP’s slogan was ‘Workers of the world unite.’ While casteism in Christianity has continued, the GPP saw everyone as one. They talked about the proletariat against the capitalists in an independent India.”

Perhaps it is their neglect of intersectionality that formulates the GPP’s biggest criticism. With all their skepticism of the Church and dominant Catholic figures, it is regrettable that the GPP did not intervene with Goa’s rampant casteism—a largely abandoned issue. The intersection of class and caste in Goa’s ever-confusing political tapestry is too large a facet to gloss over. And yet, the state’s population had already been fragmented into a multitude of categories, each with a different reaction to the Brahminical system.

“The Portuguese didn’t interfere with the caste system—they just converted the locals,” Pereira-Naik continued. “The Saraswats were converted on the condition of being allowed to carry on with the caste system. The Church never had any objections.” Accordingly, Hindu Brahmins became Roman Catholic “Bamonns”; Kshatriyas and certain Vaishya Vanis became “Chardos”; Vaishyas, “Gauddos”; and Shudras, Dalits, and Adivasis became “Sudirs.”

A friend coming from a Goan Catholic household recently remarked, drawing observations from her own family, how caste-oppressed Catholics from impoverished backgrounds tend to glorify Portuguese colonialism, to this day, regarding it as their only escape from the oppressive Brahminical structure. While Ambedkarite thought did eventually enter Goa—as Ambedkarite writer Dadu Mandrekar identifies in his 1997 book Bahishkrut Gomantak (Untouchable Goa)—it had but a minuscule impact on the primarily caste-blind Goan society.

The Conflict Between Communism and the Church

Gerald Pereira famously had a bone to pick with the Church. Despite being born into a family of religious Goan Catholics, he was a staunch atheist who resisted the Church until his last breath. In his article “The Goan Question Reconsidered,” Pereira also criticized Vauraddeancho Ixtt for propagating Catholicism among the Proletariat.

A question arises eventually: haven’t certain thinkers already pointed out similarities between Communism and Early Christianity? For instance, in her 1905 article “Socialism and the Churches,” Rosa Luxemburg wrote about the First and Second Century Christians being ardent supporters of Communism, albeit the kind of Communism they supported was based on the consumption of finished products, not work.

Pereira-Naik explained how the Church’s antagonism toward communists came from their affiliation with the Soviet Union, which in turn tied in with Lenin’s renowned statement on religion in Socialism and Religion: Complete separation of Church and State is what the socialist proletariat demands of the modern state and the modern church. “Maybe that is why the Church felt threatened—they felt it was anti-Christian,” she suggested.

There was another reason behind the friction. “As communists, [the GPP] never wanted divisive forces among the workers,” stated Pereira-Naik. “They did not want them to identify as Hindu workers, Catholic workers, or Muslim workers. That’s the thing about Communism—a worker is a worker and a capitalist is a capitalist. If the workers started identifying themselves with different religions, there would be no unity. Vauraddeancho Ixtt focused specifically on the Catholic workers, which is why I feel that [Pereira] was against it.”

My grandfather, Nagesh Palekar, a former worker at a unit of Premier Automobiles Limited in Kurla, Mumbai, vividly recalled working alongside fellow Konkani migrants. While there was no communal or regional friction among the workers outside Goa as such, a large number of them, he pointed out, were Goan Catholics, who resided primarily in localities such as Mahim, Girgaon, Byculla, and Bandra.

“Goan Catholic workers were employed in large numbers in automobile manufacturing plants, or as automobile mechanics,” he recounted. “They migrated to Mumbai and lived in clusters. Konkani migrant workers consisted of both Hindus and Catholics from Goa, Karwar, and Mangalore, but there were mainly Goan Catholic workers in the factory I worked at.”

These migrant workers stayed at residential clubs or “kudds” started by fellow Goans in the city. Antonio Nativade Timotio Barretto, the general secretary of Club of St. Anthony, Deussua at Mazgaon, stated how these kudds would be segregated based on the village these migrants came from. There would be kudds specifically for people from Carmona, Cuncolim, Assagao, Ponda, Quepem, Marcela, Divar—the list goes on.

“These clubs generally permitted Goan Catholics, but would occasionally allow a Hindu friend to stay over. Mangalorean Catholics had their own clubs too, though fewer in number,” Barretto said.

The Crucial Legacy of the GPP

At the time of Palekar’s attack, Comrade George Vaz was hiding with his companions in a forest near Surangi. The team set out towards Khandvel in search of their comrades and were surprised to find AGD associates walking from the same direction. The two groups stood facing each other for a moment, ready to fight almost reflexively. But after a moment’s consideration, Vaz sensed that the AGD now had the backing of the Mumbai Police Department and attempted to clear the air through conversation, which did not yield much luck.

In fact, it only made things worse—the cops instantly caught hold of Vaz and locked him up in the Silvassa jail. This unreasonable violence was the catalyst for a larger plan hatched by I.G.P. Nagarwala on the instruction of then-Prime Minister Morarji Desai of the Janata Party, in a desperate attempt not to let the credit for liberating Dadra-Nagar Haveli go to the communists.

At the onset of the 60s, Goa’s communist unit had started watering down considerably, as the conversation of being one with the Indian state took precedence. The GPP’s biggest ambiguity lay in its ideology of combating colonialism with nationalism, and its lack of access to better resources did not help. This marked a stark departure from the Marxist worldview on which they had built their unit. Despite initial tensions, the GPP later joined forces with some members of AGD and other anti-colonial groups, regardless of political ideology. “By the 1960s, Goa’s future was subsumed by the wider Indian debate of getting all the Princely states into one nation,” Noronha identified.

While far from ideal, it isn’t hard to see why the GPP took a step in this direction. Hundreds of freedom fighters were being martyred for the cause of liberation, without any stable backing. In such an exasperating climate, it was deemed urgent to come to a common middle ground. The team eventually turned to Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru for help.

“When Pandit Nehru invited a committee of eleven members, Advocate Vishwanath Lavande [of AGD] was one of the parties and so was my father,” remarked Pereira-Naik, highlighting the newfound coalition. “People in the committee were cutting across political lines—they wanted Pandit Nehru to do something to get rid of the Portuguese.”

The Annexation of Goa was finally carried out by the Indian Armed Forces in December 1961. Yet, Goa wasn’t entirely relieved, for there was an incoming flurry of brand-new political decisions—the latest proposal for a merger with the neighbouring state of Maharashtra; the impending status of the native language, Konkani; the large influx of up-and-coming political parties in the region, among other questions.

However, the more concerning issue was the dismantling of Goa’s communist core. After holding on their own for nearly a decade, the GPP disintegrated following Goa’s liberation in 1961, leaving behind a legacy remembered only by a select few. Members either remained communists campaigning for their politics individually or joined bigger political parties such as the Congress. Palekar joined the CPI’s National Council shortly after and became the general secretary of the state of Goa. Pereira made a name for himself as a charismatic trade union leader in the region before his unfortunate demise in 1976.

Today, Goa is still torn between the two religions. Its battle-hardened communist past has palpably ceased to exist. What remains now is a faint echo from the past. In such trying times, the GPP’s legacy remains a powerful reminder of the land’s radical history, making its archival the need of the hour.

Acknowledgments:

I would like to extend my thanks to all my sources as well as my friends, peers, and guides who helped me write this essay: Zara; Kritika Sharma; Zenia Braganza; Elroy Pinto; Nikhil Baisane; Antonio Nativade Timotio Barretto; and my grandfather, Nagesh Palekar. I would also like to acknowledge the role of Lokvangmay Grih, Prabhadevi; Marathi Granth Sangrahalaya, Thane; and Central Library, Patto, Panaji, that helped me access the resources required for research behind this essay.

Notes:

The title of this essay is a loose English translation of Govyachya Kshitijavaril Laal Pahaat, one of the chapters in Prof. Mense’s book Goa Mukti Sangramat Communistanche Yogdaan. The incident that the essay opens with has also been taken from the same source, with the author’s consent.

Related Posts

When Goa’s Horizon Dawned Red: The Forgotten History of Communism in the State

Dadra and Nagar Haveli, August 1954—a unit of revolutionaries was marching to Khanvel village. Led by Comrade Narayan Palekar, the group consisted of masses from India’s western coast: the Konkani people of Goa, the Marathi people of Mumbai, and the Warli people of Surangi. Devoid of any weapons for self-defence, they marched with their heads held high, shielded by nothing but the unwavering call for liberation.

It was a mere seven years since India had received independence from British rule in 1947. Still, the country was far from liberated. Regions like Goa, Dadra-Nagar Haveli, and Diu-Daman were under the fascist Salazar regime, still largely ignored by the rest of the nation. A resourceful communist, Palekar hailed from Goa, but his objective wasn’t limited to freeing his hometown, even though the task started there. It extended to freeing every part of the country still under Portuguese rule first, and the systemic evils of capitalism and imperialism next.

Suddenly, a jeep screeched over. Two armed figures stepped out. It was Prabhakar Sinari and Prabhakar Vaidya from the Azad Gomantak Dal. Palekar’s shoulders relaxed upon seeing the two familiar Goan fighters; after all, he was acquainted with one of their members, Vishwanath Lawande. But after a moment of careful consideration, it dawned on him that the two weren’t there to extend support—they had arrived to counter their revolution.

Chaos was unleashed upon the troupe. Palekar, along with his comrade Dr. Sawant, was dragged into the jeep, hands tied. The vehicle headed off to an unknown destination. When it finally halted, they saw a new figure emerging before them. It was Vishnu Bhople from the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), an axe in one hand, ready to strike at his targets. Palekar screamed for help, and while he narrowly escaped the attack, a loud lathi blow from someone else landed on his head, leading to a severe injury.

While Palekar was eventually nursed back to good health, the day’s happenings presented a crucial revelation: this was a ploy orchestrated by the RSS, a Hindu nationalist political unit, in collaboration with the Azad Gomantak Dal, a religiously motivated anti-colonial Goan group that ran on similar Hindutva ideology. This scheme was constructed to curb the efforts of communist parties; a direct result of the growing wave of Red Scare in the country, led by religious outfits and the Government of India, who feared threats to national sovereignty, thanks to the communist-led Telangana Rebellion (1946-1951).

The common objective of freeing India from a foreign fascist rule wasn’t enough for the differing political units to look past their prejudices. Palekar—one of the founders and leaders of the Goan People’s Party, an atheistic anti-colonial group built on Marxist ideals—had become the latest target of a vindictive attack.

Goa and communism are often not uttered in the same breath. The iconic red flag bearing the hammer and sickle is commonly associated with the states of West Bengal and Kerala, thanks to their long Marxist history. But while looking for regional Konkani publications for a college assignment, I stumbled upon the weekly Romi-Konkani newspaper Vauraddeancho Ixtt, which literally translates to “Workers’ Friend.”

The name enthralled me. As a Marxist hailing from a Konkani-speaking family, the thought of an unheard-of worker-centric publication in my native place was fascinating.

But the more I read about the paper, the more I realized that it wasn’t supposed to be a Marxist opuscule but was, in fact, created to shield the religious working class of Goa from the “growing communist propaganda” in the state. “What communist propaganda?” I wondered, and thus began my journey into the rabbit hole that is Goa’s hidden communist surge.

A Brief Religious History of Goa, and the Formation of the Goan People’s Party

Goa has had a complex religious history spanning several centuries. Popular media that identify Portuguese travellers as the first settler-colonialists in the land fail to excavate the rest of its extensive history. In his 2023 book Ajeeb Goa’s Gajab Politics, author Sandesh Prabhudesai points out, “[t]he history of Goa does not begin with the Portuguese conquest of Goa in 1510. Rather, it ends with the end of Portuguese colonization, just 60 years ago.”

He goes on to debunk the common misconception of Gaud Saraswat Brahmins being the original inhabitants of the region, thus proving that the land had, in fact, been doubly colonised—initially by the Brahmins, later by the Portuguese.

The indigenous people of Goa included tribes such as the Gowdas, Kunbis, and Dhangars, often agriculturists and fisherfolk by profession, who practised their own distinct faiths. Somewhere between 1650 and 700 BCE, the arrival of Gaud Saraswat Brahmins in the region also marked the induction of Brahminism in the land; ultimately, the indigenous population was shelved into the lowest tiers of the caste hierarchy.

The arrival of Portuguese general Afonso de Albuquerque in 1510 signalled the start of Portuguese colonialism in the region. While Christianity had existed in India before the arrival of Portuguese settlers, it was under this new regime that Goan locals were vigorously mass converted. The Church was at the centre of this evangelist equation.

It was in this tense religious climate, from the late 1900s to the early 1910s, that people started seeking out higher education. Male students from well-to-do families would be encouraged to pursue higher education in cities like Mumbai and Belgaum—and if possible, abroad—which exposed them to an entirely unexplored treasure trove of knowledge. Professor Anand Mense explains in his 2011 book Goa Mukti Sangramat Communistanche Yogdaan (The Contribution of Communists in Goa’s Liberation Struggle) that it was this pursuit of higher education in larger urban centres outside Goa that sparked revolution among its youth.

There are several instances of this. Damodar Dharmananda Kosambi, the torch-bearer for Marxist historians in India, hailed from a Goan Konkani family and developed an interest in Marxism after accompanying his father to the United States and enrolling at Harvard University. Tristao de Braganza Cunha, the pioneer of Goa’s liberation struggle, was introduced to Marxist thought while pursuing higher education in Paris in 1912, after being greatly influenced by the Paris Commune.

The cause of Goa’s liberation was further taken up by the Portuguese Communist Party in 1921, which routinely called for the removal of the Portuguese empire in its publication Avante!.

Goa’s fledgling freedom struggle came to a standstill after António de Oliveira Salazar became Portugal’s Prime Minister in 1932. The oppressive Portuguese colonialism had now turned into a rigid fascist regime. Civil liberties were at stake. It had become imperative to take immediate action. It was under these drastic circumstances that Goa’s first proper communist movement unfolded.

In Mumbai, a new wave of progressive Goan student-youth, which flatly refused to be tied down by religion, had also decided to start their own communist unit. They aimed for the complete liberation of their motherland from both colonialism and religious dogma. In 1948, the ambitious Goan People’s Party, or GPP for short, was formed, helmed by General Secretary George Vaz and Secretary Narayan Palekar.

The GPP had several influences across the board, including the Paris Commune and the Soviet Union. Furthermore, it was modeled on the ideas of not only Marx and Lenin, but also political figures close to home like M. N. Roy and T. B. Cunha. The party operated mainly from Mumbai but also received support from like-minded political units in neighbouring cities like Pune and Belgaum.

The Ambiguity of Decolonial Political Ideology: Hindutva, Anti-Colonialism, and Communism

The ambiguity of political ideology in the party’s name can be attributed to the cancerous growth of the Red Scare across India. Any leftist party with the word “communist” in its name was automatically exposed to heightened risks. Outside the Portuguese and Indian states, communists in Goa attracted disdain from religious organizations, including Clerical and Hindutva groups. The Church has historically despised communists; the same can be reflected in Goa’s pre-independence Catholic mass media. One such example is Vauraddeancho Ixtt, the Goan periodical published by the Society of Pilar, a Roman Catholic society for men.

In a phone interview, Father Peter Francis, the manager of the publication, talked about how pre-independence periodicals/papers could not publish anything against the Portuguese government, as mass and broadcast media like newspapers were largely controlled and censored. “The punishment for speaking against the Portuguese government was a decree for withholding the publication for 90 days,” he mentioned, elaborating on how this particular “anti-communist” stance was a response to the GPP’s open atheism. The endless tug-of-war between Catholics and communists formed the baseline of Goa’s redundant political struggle.

“My personal reading is that the misreading of a selectively truncated half-quote of Marx—opium of the people—led to a lot of misunderstanding between religion and the Left,” observed journalist Frederick Noronha, who is based in Saligão, Goa. “The Left also mishandled the issue, and continues to go by what its critics say, rather than what Marx meant. To my mind, a more harmonious reading between religion and the Left can be seen in the growth of Liberation Theology in Latin America—which also made its way to Sri Lanka, and to a lesser extent to Goa in the 1970s and 1980s—as well as books like Fidel on Religion.”

Besides Catholicism, the 1940s were also the time when a fresh wave of Hindu nationalism was brewing throughout British India and then the newly formed Indian state. Moreover, the recent success of the Telangana Rebellion (1946-1951)—an armed peasant uprising against feudal exploitation and the Nizam of Hyderabad’s oppressive rule, led by the Communist Party of India—was seen as a threat by the erstwhile authorities, leading them to cement a strong sense of anti-communist attitude in the minds of the Indian middle class. This anti-communist attitude was also usually what led to in-fighting between political groups on either side of the spectrum, building towards the same end: decolonizing.

But decolonizing what exactly? The GPP had a broader goal in mind; the Azad Gomantak Dal (AGD), on the other hand, navigated the idea with the myopic perspective of eradicating the “foreign” religion as a remnant of colonialism.

“[The ideology of] AGD is a mix of anti-colonialism together with some degree of Hindutva,” explained Noronha. “Interestingly, the anti-Portuguese campaign fit in rather well in the Hindutva worldview: foreign rulers, religious bigotry, destroying native faiths, and such. So it needs a rather different reading from the experiences of the rest of India. Plus, it came a decade and a half later, after Gandhi’s assassination [in 1948], when groups like the RSS got enough time to rethink their beliefs, and the implications of the same.”

“Portugal was conservative,” Noronha continued. “In the early 1900s, Republican thought took hold in Portugal. But this also led to a big rise of the Left as an oppositional force in the 20th century. This can be seen from former Portuguese colonies such as Angola, Mozambique, and East Timor, where the history of the Left has been sometimes complex and complicated, but also influential.”

It’s hard to put a finger on Goa’s religious mosaic. My recent visit to my native place in Ponda, a Hindu-majority town, reminded me of all the times I had come here as a kid, amused by the numerous religious trinkets that the region is eternally brimming with. In most public places, figurines of Jesus and Mother Mary are worshipped alongside portraits of Manguesh and Shantadurga (regional variants of Hindu deities). I recall seeing objects of both Christian and Hindu faith placed in a synchronous arrangement in an inter-city bus; a miniature Cross placed neatly alongside a miniature idol of Ganesha.

It appears as a rosy feel-good picture of textbook secularism on the outside, but it does not take long to discover how this quasi-religious façade has unraveled in Goa’s morbid communal politics. “Goa is not a relatively secular region,” Noronha asserted. “That is deceptive. That Goa has had a form of soft Hindutva in power for much of the 1960s and 1970s is a well-kept secret. The Opposition then was also largely Catholic-supported. Even later, Congress politics reflected this. Since 2012, the BJP has been doing just about what it pleases, and most folks here tend to get easily polarized.”

It’s not hard to see why the GPP endorsed the complete abolition of religion.

Noronha differs, however. “Because of the hard line that the Left took on religion—again, a misreading of Marx—I think most serious Leftists would not be able to follow any religion, in conscience,” he said. “It is also true that the Church and Hindu society were rather conservative in Goa, which is why many of those fighting the Portuguese State also moved away from their religion, especially Catholicism, as Church and State were seen as closely interconnected in those times.”

Mass Media and the GPP’s Neglect of Caste Intersectionality

Mass media played a key role in the GPP’s curriculum. Even though Portuguese print media hogged the most space among Goan locals, resistant publications distributed by the GPP were tacitly getting the work of decolonization done in neighbouring regions. Goan Age, the GPP’s primary print organ, was launched shortly after their formation in 1948, with Gerald Pereira serving as the editor.

The publication featured essays, thought pieces, columns, op-eds, and illustrations condemning Portugal’s regime, as well as obituaries of martyrs fallen for the liberatory cause. The articles were written in both English and Romi-Konkani by several party members, writers, and scholars, including Pereira, Palekar, Berta M. Braganza, Dr. George D’Silva, and Victor Gonsalves. Correspondents from Japan and Portugal, who were sympathetic to the effort, were also occasionally featured.

I visited Mrs. Lara Pereira-Naik, Gerald Pereira’s daughter. Sitting in Panaji’s reputed Central Library, we engaged in an informative conversation about her late father’s involvement in the struggle, his views on religion, and his role in workers’ movements. “The GPP was not bothered about religion,” she narrated. “In fact, my father himself was against religion. The GPP’s slogan was ‘Workers of the world unite.’ While casteism in Christianity has continued, the GPP saw everyone as one. They talked about the proletariat against the capitalists in an independent India.”

Perhaps it is their neglect of intersectionality that formulates the GPP’s biggest criticism. With all their skepticism of the Church and dominant Catholic figures, it is regrettable that the GPP did not intervene with Goa’s rampant casteism—a largely abandoned issue. The intersection of class and caste in Goa’s ever-confusing political tapestry is too large a facet to gloss over. And yet, the state’s population had already been fragmented into a multitude of categories, each with a different reaction to the Brahminical system.

“The Portuguese didn’t interfere with the caste system—they just converted the locals,” Pereira-Naik continued. “The Saraswats were converted on the condition of being allowed to carry on with the caste system. The Church never had any objections.” Accordingly, Hindu Brahmins became Roman Catholic “Bamonns”; Kshatriyas and certain Vaishya Vanis became “Chardos”; Vaishyas, “Gauddos”; and Shudras, Dalits, and Adivasis became “Sudirs.”

A friend coming from a Goan Catholic household recently remarked, drawing observations from her own family, how caste-oppressed Catholics from impoverished backgrounds tend to glorify Portuguese colonialism, to this day, regarding it as their only escape from the oppressive Brahminical structure. While Ambedkarite thought did eventually enter Goa—as Ambedkarite writer Dadu Mandrekar identifies in his 1997 book Bahishkrut Gomantak (Untouchable Goa)—it had but a minuscule impact on the primarily caste-blind Goan society.

The Conflict Between Communism and the Church

Gerald Pereira famously had a bone to pick with the Church. Despite being born into a family of religious Goan Catholics, he was a staunch atheist who resisted the Church until his last breath. In his article “The Goan Question Reconsidered,” Pereira also criticized Vauraddeancho Ixtt for propagating Catholicism among the Proletariat.

A question arises eventually: haven’t certain thinkers already pointed out similarities between Communism and Early Christianity? For instance, in her 1905 article “Socialism and the Churches,” Rosa Luxemburg wrote about the First and Second Century Christians being ardent supporters of Communism, albeit the kind of Communism they supported was based on the consumption of finished products, not work.

Pereira-Naik explained how the Church’s antagonism toward communists came from their affiliation with the Soviet Union, which in turn tied in with Lenin’s renowned statement on religion in Socialism and Religion: Complete separation of Church and State is what the socialist proletariat demands of the modern state and the modern church. “Maybe that is why the Church felt threatened—they felt it was anti-Christian,” she suggested.

There was another reason behind the friction. “As communists, [the GPP] never wanted divisive forces among the workers,” stated Pereira-Naik. “They did not want them to identify as Hindu workers, Catholic workers, or Muslim workers. That’s the thing about Communism—a worker is a worker and a capitalist is a capitalist. If the workers started identifying themselves with different religions, there would be no unity. Vauraddeancho Ixtt focused specifically on the Catholic workers, which is why I feel that [Pereira] was against it.”

My grandfather, Nagesh Palekar, a former worker at a unit of Premier Automobiles Limited in Kurla, Mumbai, vividly recalled working alongside fellow Konkani migrants. While there was no communal or regional friction among the workers outside Goa as such, a large number of them, he pointed out, were Goan Catholics, who resided primarily in localities such as Mahim, Girgaon, Byculla, and Bandra.

“Goan Catholic workers were employed in large numbers in automobile manufacturing plants, or as automobile mechanics,” he recounted. “They migrated to Mumbai and lived in clusters. Konkani migrant workers consisted of both Hindus and Catholics from Goa, Karwar, and Mangalore, but there were mainly Goan Catholic workers in the factory I worked at.”

These migrant workers stayed at residential clubs or “kudds” started by fellow Goans in the city. Antonio Nativade Timotio Barretto, the general secretary of Club of St. Anthony, Deussua at Mazgaon, stated how these kudds would be segregated based on the village these migrants came from. There would be kudds specifically for people from Carmona, Cuncolim, Assagao, Ponda, Quepem, Marcela, Divar—the list goes on.

“These clubs generally permitted Goan Catholics, but would occasionally allow a Hindu friend to stay over. Mangalorean Catholics had their own clubs too, though fewer in number,” Barretto said.

The Crucial Legacy of the GPP

At the time of Palekar’s attack, Comrade George Vaz was hiding with his companions in a forest near Surangi. The team set out towards Khandvel in search of their comrades and were surprised to find AGD associates walking from the same direction. The two groups stood facing each other for a moment, ready to fight almost reflexively. But after a moment’s consideration, Vaz sensed that the AGD now had the backing of the Mumbai Police Department and attempted to clear the air through conversation, which did not yield much luck.

In fact, it only made things worse—the cops instantly caught hold of Vaz and locked him up in the Silvassa jail. This unreasonable violence was the catalyst for a larger plan hatched by I.G.P. Nagarwala on the instruction of then-Prime Minister Morarji Desai of the Janata Party, in a desperate attempt not to let the credit for liberating Dadra-Nagar Haveli go to the communists.

At the onset of the 60s, Goa’s communist unit had started watering down considerably, as the conversation of being one with the Indian state took precedence. The GPP’s biggest ambiguity lay in its ideology of combating colonialism with nationalism, and its lack of access to better resources did not help. This marked a stark departure from the Marxist worldview on which they had built their unit. Despite initial tensions, the GPP later joined forces with some members of AGD and other anti-colonial groups, regardless of political ideology. “By the 1960s, Goa’s future was subsumed by the wider Indian debate of getting all the Princely states into one nation,” Noronha identified.

While far from ideal, it isn’t hard to see why the GPP took a step in this direction. Hundreds of freedom fighters were being martyred for the cause of liberation, without any stable backing. In such an exasperating climate, it was deemed urgent to come to a common middle ground. The team eventually turned to Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru for help.

“When Pandit Nehru invited a committee of eleven members, Advocate Vishwanath Lavande [of AGD] was one of the parties and so was my father,” remarked Pereira-Naik, highlighting the newfound coalition. “People in the committee were cutting across political lines—they wanted Pandit Nehru to do something to get rid of the Portuguese.”

The Annexation of Goa was finally carried out by the Indian Armed Forces in December 1961. Yet, Goa wasn’t entirely relieved, for there was an incoming flurry of brand-new political decisions—the latest proposal for a merger with the neighbouring state of Maharashtra; the impending status of the native language, Konkani; the large influx of up-and-coming political parties in the region, among other questions.

However, the more concerning issue was the dismantling of Goa’s communist core. After holding on their own for nearly a decade, the GPP disintegrated following Goa’s liberation in 1961, leaving behind a legacy remembered only by a select few. Members either remained communists campaigning for their politics individually or joined bigger political parties such as the Congress. Palekar joined the CPI’s National Council shortly after and became the general secretary of the state of Goa. Pereira made a name for himself as a charismatic trade union leader in the region before his unfortunate demise in 1976.

Today, Goa is still torn between the two religions. Its battle-hardened communist past has palpably ceased to exist. What remains now is a faint echo from the past. In such trying times, the GPP’s legacy remains a powerful reminder of the land’s radical history, making its archival the need of the hour.

Acknowledgments:

I would like to extend my thanks to all my sources as well as my friends, peers, and guides who helped me write this essay: Zara; Kritika Sharma; Zenia Braganza; Elroy Pinto; Nikhil Baisane; Antonio Nativade Timotio Barretto; and my grandfather, Nagesh Palekar. I would also like to acknowledge the role of Lokvangmay Grih, Prabhadevi; Marathi Granth Sangrahalaya, Thane; and Central Library, Patto, Panaji, that helped me access the resources required for research behind this essay.

Notes:

The title of this essay is a loose English translation of Govyachya Kshitijavaril Laal Pahaat, one of the chapters in Prof. Mense’s book Goa Mukti Sangramat Communistanche Yogdaan. The incident that the essay opens with has also been taken from the same source, with the author’s consent.

SUPPORT US

We like bringing the stories that don’t get told to you. For that, we need your support. However small, we would appreciate it.