‘Palestine civil resistance will succeed, for you can kill a person, not a movement’—a conversation with Anne de Jong

With a military manpower of 3,600,000 and defense budget of $20 billion for a population almost as small as that of the city of Amsterdam, Israel has one of the most advanced armies in the world. Their nuclear arsenal is estimated to possess at least 80 warheads, at par with India and Pakistan. Israel’s Missile Defense System is a multi-tier architecture that includes the Arrow to intercept long-range ballistic missiles, David’s sling to intercept medium range rockets and, the Iron Dome. All of these use highly sophisticated technology that can not only detect and track missiles from as far away as 300 miles but also have the capability to determine where the incoming projectile will land. The Israeli military can remotely operate Guardium robots (Umanned Ground Vehicles) equipped with sensor cameras and weapons, deployed on the border with Syria and Gaza strip, to safely avoid any physical contact with opposing forces.

Now consider the Palestinians – they have no air force and no navy; no tanks and no missiles. Only 50 armored vehicles (nearly all in the West Bank) and offensive ground forces of 62,200 people. Most of their rockets are homemade that are incapable of inflicting mass civilian casualties. Norman Finklestein quotes a counter intelligence veteran of the U.S. CIA who spent his career monitoring Israeli and Palestinian military capabilities: “Hamas’ rockets can kill people and they have, but compared to what the Israelis are using, the Palestinians are firing bottle rockets.” On top of this, the Israeli state practices a near total control not only on the movement of goods and people but also on the natural resources available to the landlocked Palestinian population. A third of the population has no access to electricity, and water is limited to 60-90 liters per person per day while some are forced to survive on 10-20 liters per day. A study conducted on the Israeli-Palestinian Joint Water Committee by the University of Sussex reveals a relation so asymmetrical the author deems it inappropriate to classify it as an instance of international water ‘cooperation’ since Israel practically ‘dominates’ all ground and surface water resources.

Comparing Israel, with all its military might and overwhelming Western support, and the Palestinians, prisoners in their own land, humiliated and helpless, one is left perplexed at the dominant media and scholarly narrative on their ‘conflict’. Why is the prism from which this issue viewed so skewed? Given the lopsided power dynamic, can the issue ever be resolved? To shed light on these questions and to delve deeper into the nature of the relationship between Israel and Palestine, we talk to Dr. Anna De Jong.

Anne de Jong is a political anthropologist and activist. She has extensively studied civil resistance in the Middle East. During her research in the occupied territories of Palestine, she noticed the propensity of academia to view Israel and Palestine as two equal entities fighting for peace—a concept she realized was far from accurate. Anne has dedicated her work to right this false dichotomy by exposing the unequal power relations between the two. In this interview for The Polis Project with Sara Azeem, she discusses her research on the Zionist hegemony and forms of violence and their effect on the Palestinian colonial struggle. Currently based in South Africa, de Jong is looking at international solidarity activism towards Palestine and the role of outside pressure, mainly from the Boycott, Divestment, Sanctions movement.

Sara Azeem: There are conflicts all around, what about the Middle East made it attractive for your study?

Anne de Jong: Well, first I think was the complete shock that everything you knew about a particular area was wrong. I considered myself a critical, open-minded student already but when I went there, it was so different. So completely different in every aspect that I just couldn’t stop wondering how that came about. Part of that is, as I write in some of my articles, the idea that conflict has two sides, as is the everyday experience of living in a Palestinian town, its culture. And everything you had previously learned was so opposite to reality that it really drew my attention. It is one of the most horrific injustices and it’s ongoing. I am an academic/activist or activist/academic and I think it is impossible to disconnect the universities—the academy—and knowledge from power and politics in the world around us. It should not be disconnected, like on one side there is the academy and on the other the society that we study. It [academy] is part of how we look at life and how we make policy and how materials are distributed and how we view the world around us. Given this, if you encounter a situation so unjust, I believe, to not write about it is almost being complicit.

Could you share a moment, or an example, to elaborate on this?

One that I encountered immediately was the idea that there is an Israel and there is a Palestine. People think that there is an Israel and next to it there is a Palestine and they are fighting each other. And when you get there, you see there is no simple dichotomy, no binary distinction, not geographically, not demographically, not ideologically. Geographically the region that we know as Israel and Occupied Palestine Territories including Gaza and East Jerusalem is all under Israeli control one way or another. There is no Palestinian entity but rather the Bantustans of apartheid South Africa. Israel never set their outer borders. If you cross the 1967 Green Line (border), there’s no sign, you wouldn’t even notice it. You go in and out of it without noticing any distinction between the Israel where Israelis live and the Palestine where Palestinians live. This is because 1.5 million Israeli citizens are Palestinians and more than 500,000 Israeli settlers live in the West Bank. So that rigid, binary distinction just holds no reflection of the reality on the ground.

How important do you think is the lens from which to view the conflict? To many westerners it is a story of intransigent conflict while others argue it is a colonial struggle…

It is very hard to avoid even in my own language but I try to challenge the idea that there is such a thing as the Israel-Palestine “conflict”. I looked at what I call the peace and conflict paradigm—the assumption of two sides with the desired solution of peace between them—and I object to this paradigm that is seen as “objective” or “neutral”. It is actually a very biased paradigm with far-reaching consequences.

Geographically you have Gaza, which is besieged; in Israel proper, there is institutionalized discrimination; then there is Jerusalem where there is apartheid; and West Bank is militarily occupied. So there are no two sides, let alone countries.

Calling it a ‘conflict’ really sanitizes, even legitimizes, very unequal power relations. On one hand is Israel, the country that has the fourth most powerful army in the world, and on the other are a scattered, dispossessed people who struggle for freedom, self-determination, and even basic human rights such as freedom of movement. So there are no two sides or two equal sides. It also obscures the idea of peace and conflict. Presenting it as a ‘conflict between two sides’ obscures what it is in fact: a classic human rights struggle.So, it is not about Israel on one side and Palestine on the other. It’s also not about Jews on one side and Muslims on the other, or even Israel versus the Arabs. It is a conflict between those who agree or yield to Zionist exceptionalism and believe that fundamental human rights and civil rights depend on one’s ethnonationalism.

Israel is a democracy for its Jewish citizens, that’s absolutely true—they have the right to vote, the right to water and basic facilities, and they can go to a judge or the police if they need to. This is not so for Palestinians on the West Bank or Gaza or even for Palestinian citizens of Israel because those rights are dependent on your ethnonationalism, on whether you are Jewish or not. So the whole peace and conflict paradigm basically obscures the fact that it’s between those who agree with Zionist ethnonationalism and those who say well, hold on, human rights should apply to all.

In your work, you argue for an emphasis on the knowledge-making process and revival of subjugated knowledge to understand what you call the ‘cacophony of the Palestinian experience’. Could you elaborate?

I wanted to ask some questions: How did we come to think of conflict as a neutral term? And what are the origins of how we came to think about the ‘Israel-Palestine conflict’ in terms of ‘conflict’ and how it became normal and objective. So I conducted research in the genealogy of conflict. Genealogy is a methodology, which stems from looking at the power behind knowledge. As Foucault, who followed Nietzsche, said, genealogy looks at the force relations behind the interpretations of history—how we came to look at history the way we do, how we speak and think, the possibilities of thinking about situations, how they came about, how it all gets normalized…I did archival research on when people started to speak about Israel-Palestine in terms of conflict, specifically looking at early Zionist writings and correspondence. I found it was actually not at all a spontaneous process but rather a very consciously advocated Zionist strategy that they discussed among themselves and consciously applied to counter accusations of settler colonialism.

Look at it in the context of that time: in late 19th century when political Zionist movement came about, settler colonialism was not yet condemned the way we do now. It was a legitimate enterprise. Jewish people at that time in opposition to pogroms, for example in Russia, decided there needed to be a national movement to create a State and they chose to do so in Palestine. But they were met with resistance not only from the Palestinians who said ‘hold on, we’re already here’ but also from Jewish leaders and authorities in the West because they believed that Judaism is not about a nation-state as Zionism, it is about the Torah. Early on, the Zionist movement was opposed by Jewish religious leaders like Rabbi Samson Raphael Hirsch (1808 – 1888), who rightfully observed at the time that there was a move from being Jewish because of what you believe, the Torah, to being Jewish because of what you are, an ethnic connection.Once the Zionist movement had made some success and started the immigrant stream to Palestine, the opposition grew with Zionists particularly accused of settler colonialism.

To counter this, Ben Gurion, a known Zionist, said ‘well, we need to broaden this framework; they are looking at us like we are colonialists imposing ourselves on an indigenous population, so we broaden the framework and make it about us, the Jewish, small, persecuted nation returning to our land versus a big aggressive Arab Goliath’. He said we should not ever speak about the Zionist movement and the Palestinians. Instead, we should talk about a peaceful Jewish David versus the aggressive Arab Goliath.

It changed the power dynamics. First, it became about “return” rather than colonial settlement. Second, Zionists denied Palestinians their specific national identity—who lived there before documented time—and merged them with a broader Arab entity, disconnected from their land. Third, they created the binary opposition as a small Zionist nation defending themselves rather than a settler colonial oppressor. This indeed become central to the Zionist discourse and myth not only to oppose Palestinians but also establish a Zionist base where not all Jews were immediately Zionist. Early on, it was very easy for a Jewish person to say ‘I am not a part of the Zionist movement, I am a Jew, and I am part of this synagogue’. Later, it became a lot harder to say ‘I am not a citizen’ or ‘I am not a part of this [Zionism]’.Finally, the myth became widely accepted as reality, gaining support from America and the United Kingdom (who recognized the state immediately).So if you speak out when there is a dichotomy such as this it makes you choose sides. By saying ‘I am against settler colonialism’ (which is what Israel is) you’re anti-Semitic because they merged the settler colonial movement with Judaism.

Could you talk more about how the Zionist movement played the underdog and how it gathered support internationally?

I don’t think the early Zionist movement considered itself the underdog; they very consciously portrayed it. Look at its early writings, they were very well aware of dispossessing an entire people and some even said ‘yes, regretfully but if you want Jewish majority then you have to use means necessary’. Letters between early Zionist leaders characterizes this; they discussed the force they meant to use and how they’d legitimize it for the rest of the world.So the myth turned into reality for a lot of people. You can prove and clearly make a case that this is not what happened but still for a lot of people it holds true. For many it became a really emotional matter. The Jewish diaspora grew up with a powerful propaganda machine about Israelis constantly under threat and how they are about to be pushed in the sea. But in reality Israel is the one who oppresses Palestinians. They talk about rockets from Gaza as threats but those “rockets” are homemade devices that cannot even be adequately directed to hit the targets. They have no tanks, helicopters, or soldiers who could actually combat—there is no army on the other side. There is no threat.

Internationally, one needs to understand two other support groups. One, there are many religious Zionists, not Jewish but Christian, who believe from a Biblical perspective that the Middle East is the place of return of the Messiah and they believe for the Messiah to return it has to be inhabited by Zionists. Second, we must acknowledge there is a lot of guilt about the Holocaust, as there should be. Europe was complicit with Nazi Germany. While we celebrate resistance and blame it all on the Nazis, the fact is that most European countries, for example the Netherlands, willingly extradited their Jewish population. The resistance was only from underground groups; it did not come from the State so there should be guilt about that.At the same time, the Palestinians were not the ones who created the Holocaust. It is not okay to say that because of the Holocaust in Europe, Israel and Jewish people now have the right to oppress another people. But these are the dynamics that play internationally. It is an interesting time because many of those groups and beliefs are shaking and trembling right now.

It is interesting you mentioned that and I am going to come back to this after a slight detour. You talked about revising your belief of not mixing an anthropological study with activism, how at first you avoided that but later events changed your mind and chose to function as an activist while carrying out scholarly work. Could you share a bit more about that transition.

From primary school, through high school and university you learn that academic knowledge is neutral and should be objective. Like anyone else I believed that. However, if you look at the world around, you see how it is shaped by academic knowledge; that knowledge helps us make sense of the world, so the knowledge doesn’t exist in isolation. I have asthma, I have inhalers lying around everywhere. I think of the time in Gaza visiting a friend from the years of my research. Her 12-year-old daughter died from an asthma attack because Israel wasn’t allowing medicine into Gaza. How do you work with this? How is it objective to not mention that sorrow, that pain? How is it possible to objectively describe this on one side and Israel on the other? How should I look at both experiences? Is it not scientifically more transparent and legitimate if I portray and stand for my research findings, which show very unequal power relations, that there is injustice, and it is entirely against human rights?

Academic knowledge has consequences so I might as well be aware of those, and of the power and privilege I have as an academic to influence the world around me. I am incredibly lucky that I could travel to Gaza (not anymore), but I could go to Palestine. The next logical step is to use that power and privilege and to write for the subaltern, for those denied a voice. That gradually turned into not just observing activism and resistance that I was studying but also actively placing myself as part of how the world is constructed around us. I no longer wanted to be a part of the silent majority, and I tried to use my position, knowledge, and skills. Particularly for me it came around in 2010 when a large part of my research group decided to organize a Freedom Flotilla to break the siege at Gaza.Those boats were attacked, ten people were killed, we were detained, it was very bloody, and horrific, but it did break the silence on the siege around Gaza. Before that people didn’t know that it was a very small piece of land—completely surrounded by air, sea, and land—controlled by Israel. But after this there was no turning back and it only deepened my commitment to being an activist/academic. I decided my knowledge shouldn’t be confined to libraries but should help the people that I study.

You mentioned in one of your articles that Freedom Flotilla was a microcosm of the events unfolding for the Palestinians—people were captured while news was controlled by Israel. There are parallels between what is happening now—the Grand March Home. Could you place in context how this latest series of protests by the Palestinians is yet another act of peaceful resistance by a hapless people which doesn’t get highlighted as it should.

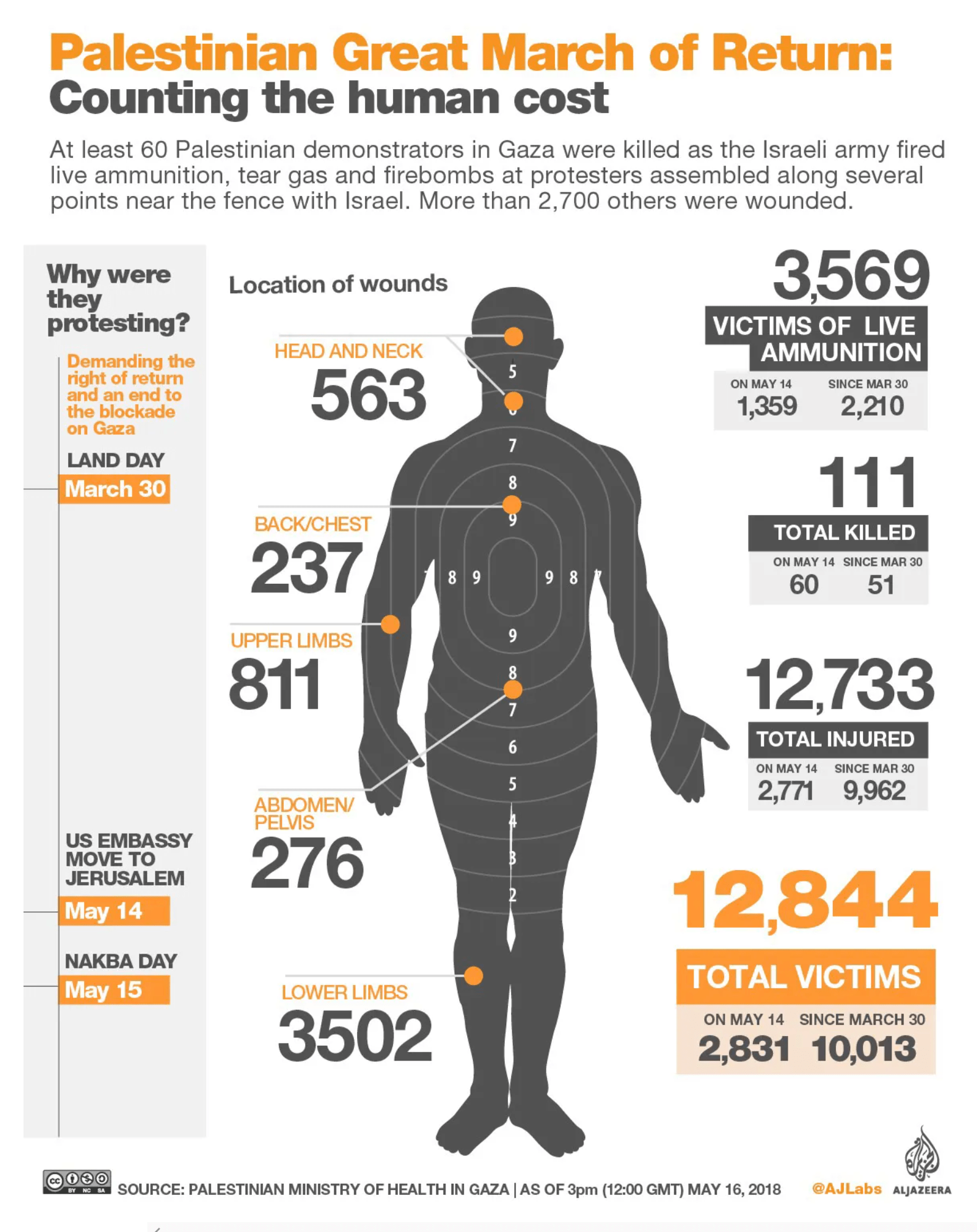

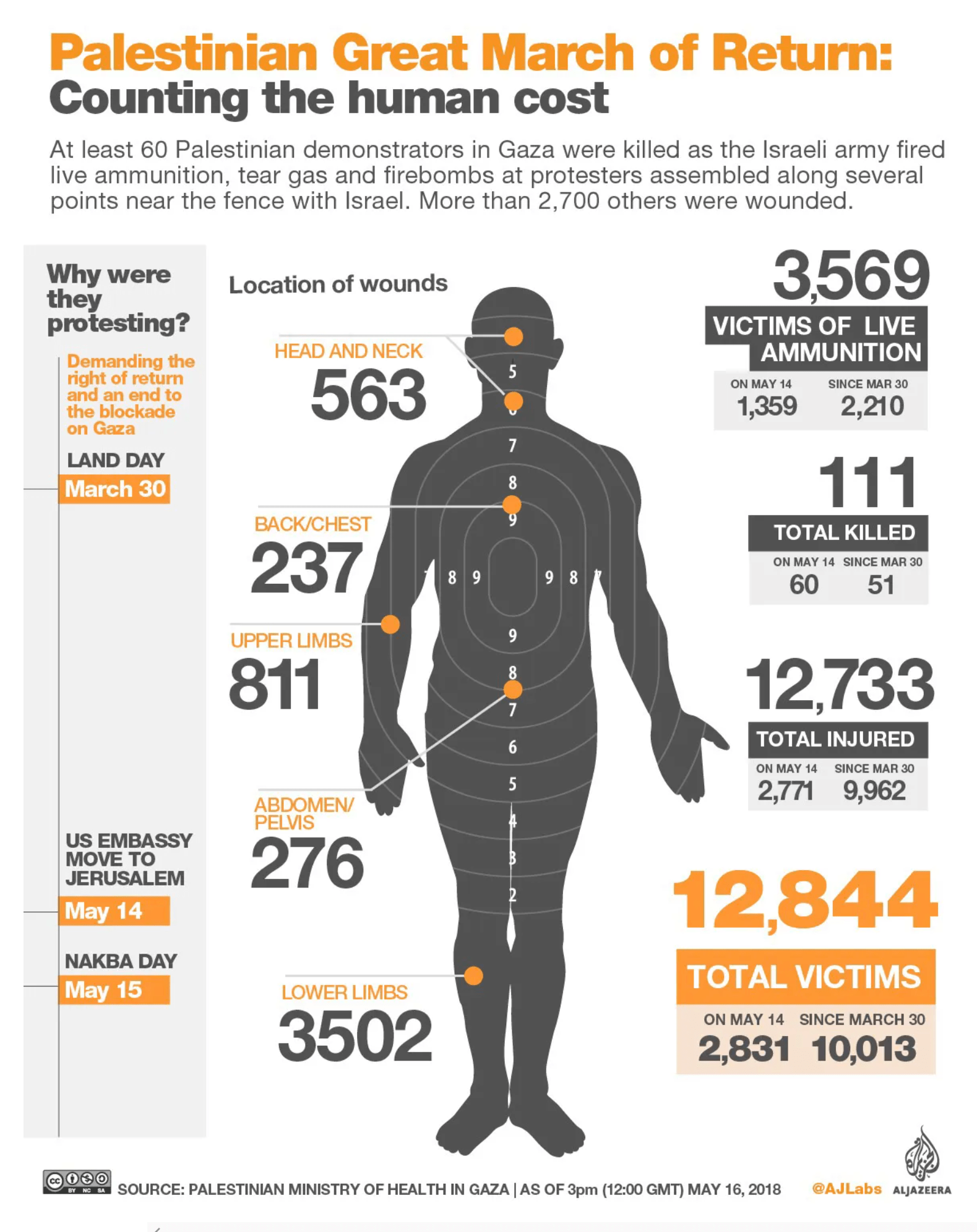

Well it’s been desperate and heartbreaking, but also positive and hopeful. It may sound strange looking at the extreme violence and deaths but I’ll explain. On one hand, it is desperate to see that a non-violent, mass protest calls upon Palestinians’ 70 years of expulsion from their land. They planned a six-week protest to claim their (internationally acknowledged) right to return. Their houses, their homes, their villages, places they were expelled from because of the 1948 Nakba (Israeli independence) are there, less than 60 miles from Jerusalem. They protest in a non-violent manner, there are no politicians, people go to the border, and they’re horrifically shot at from a distance, not even close to a “clash”. There isn’t one Israeli hurt yet the media talked about “confrontations”.

And this civil population is asking for its right not just to return but also to live in Gaza where the situation is untenable. There are only up to four hours of electricity a day, most water resources are extremely polluted, more than 40% are unemployed, they cannot leave the Gaza strip without permission from Israel.Women especially are hit hard. There’s not enough cancer treatment for breast cancer. So they are completely controlled by Israel and locked in what people call open-air prison but I say these people are not even convicted of doing anything wrong. It is like a holding cell; people protest, and get shot down. So this notion of “clashes” completely ignores the underlying power relations. It portrays Palestinians as aggressive and attacking Israel or threatening the border of Israel when there is no border. Israel refuses to state their borders because they control all the land between the sea and the river.

Then it is portrayed as a struggle between Hamas and Israel. Again, there is no such thing as a Palestinian state. Yes, Hamas is elected in the Gaza strip and Hamas was elected once upon a time, many years ago, in the West, but that completely ignores the fact that Palestinians don’t have self-determination. Hamas cannot issue a passport with which Palestinians from the Gaza strip can go about.What is interesting, and hopeful, is the dynamics are changing. They don’t allow international journalists into Gaza but with cell phones and social media the horrific images can no longer be buried under Israeli state propaganda. It exposes the unequal power relations, and it relates to people around the world who go ‘this is like gunning down of black activists in America during segregation’. I think this change is fascinating, and significant.

This brings us back to where you mentioned international support, the guilt in Europe about the Jewish extradition, and how that’s changing a bit now…

It’s very interesting. In the UK and Netherlands, the government just adopted a new definition of anti-Semitism that includes criticizing Israel. Not only does this silence political violence on an entire group of people, it is an infringement on free speech and actually equates Jewish people all around the world with Israel. These are scary developments in Europe. What’s positive is more and more Jewish people are getting vocal that it is not in their name, that it’s not what their idea, feeling, or connection with Israel is or with what Judaism means. I find that hopeful. Also what is important is in the international solidarity movement more Jewish people are speaking up because they can actually break this myth that somehow Israel speaks for all Jewish people in the world. The idea that Israel speaks for all the Jewish people in the world is anti-Semitic. Also, there is a compelling dynamic because there is now a growing group of very critical Israeli as well as international Jews who work with Palestinians and who are aware of the power mechanism. They don’t want to speak over the Palestinians but they have a voice that is heard, so they use that to give a platform to Palestinian activists in Gaza and the West Bank.

You mentioned power and resistance as an area of expertise in everyday life. Some feel resistance can’t always be peaceful. Even Mandela realized he couldn’t bring about victory through peaceful means. How can resistance work in the face of a ruthless, or lunatic (per Norman Finkelstein) Israel?

The idea that non-violent resistance is always peaceful as opposed to violent resistance is based on a couple of misunderstandings. We should think of peace activism on one hand and non-violence on the other. That’s a distinction I will come back to. But first, non-violent resistance is not holding hands and loving your enemy, it’s also not a strategy based on appealing to the heart of the oppressor. It is a strategy based on an analysis of power relations. If you look at any oppressive regime, it is not a massive, almighty monster that comes out of nowhere. On the contrary, power is always dynamic. It is never complete in that there is one side that holds all the power. You can imagine it as a house model with the roof as the oppressive regime, like the Israeli state over Palestine. That roof does not just exist; it depends on pillars of support and different pillars execute their power. A dictator who doesn’t have an army can shout all he wants but he doesn’t have the power to execute.

Then there are other pillars like the media, the military apparatus, tax collecting institutions, sanctions, imprisonment, or the near to complete monopoly on violence. Now, non-violent resistance doesn’t say ‘hey, I’m human please give me my freedom’. What it does is it attacks those pillars of support; it attacks the idea that Israel is a legitimate state. For example, them shooting down unarmed protestors shakes the idea that Israel is legitimate. It attacks the pillar of the media. So it is a strategy to very consciously break down the pillars of support so that the rooftop collapses.

You can see it in the case of Milosevic. I prefer a more recent example because Gandhi and Martin Luther King were just two. Erica Chenoweth wrote a book, Why Civil Resistance Works, and it shows that it actually works better than violent uprisings. If you attack those pillars of support to collapse the house, then there are 189 different actions ranging from boycott to protest. You can put them roughly into three categories: there is direct action, like this demonstration in Gaza right now but there is also civil disobedience, and that is where people no longer comply with this regime. For example, they refuse to pay tax, or they refuse to join the Israeli military as conscientious objectors. The third one is to build alternative routes, which is also a form of resistance because it makes the population less dependent on their oppressor. A part of that can also be the reconstruction of Palestinian homes or finding alternative media outlets around the world as you see them springing up.

So, social change happens through non-violence not because the person decides that he loves you all of a sudden. It’s either by conversion—they become convinced that they need to stop their oppressive practices—or most of the time it’s accommodation—they have to or they are forced to accept that they cannot sustain a regime. Or what would happen in the case of Israel-Palestine is that they will be forced to let go even though they don’t want to. It’s what you saw in former Yugoslavia when Milosevic gave his troops the order to shoot. The troops were standing in front of the population and were given the orders to shoot, but the police didn’t do it. He, one of the most ruthless dictators of the past 20 years, couldn’t get his orders executed because nobody listened to him anymore and his power collapsed.

If you look at non-violence as resistance, as opposed to peace activism, you see that it’s not the opposite of violent resistance. Palestine has the right, under international law, to resist an occupation in any way. It can’t be seen in opposition to violence because violence is everywhere, in any possible manner, imposed on the Palestinians. The non-violence that you see in Gaza right now does not come from a belief that there should be peace at all times. I believe they realize that violence is not the only way. It is not an alternative to violent resistance but a different strategy, one in which everybody can partake.

Then there is also an important distinction I want to make between non-violent resistance and peace activism. It’s often confused and equated with each other. Peace activism is often based on pity, or on the belief that, for example, bombing by Israel was too much. This does not break the peace and conflict paradigm. It still very much works with the Zionist idea of Israel-Palestine, so it propagates talking and dialogue between the two sides. What it really does is reproduce the unequal power relations and does not go to the heart of the problem. It just states that there are two narratives, two victims, and both are rightfully upset, which reproduces existing power relations.

For example, there are many Jewish-Israeli peace organizations like Peace Now who say ‘well the blockade is too strict’. They don’t say the blockade is unfair. You can even see the reproduction of those power relations in the decisions within that activism. The Israeli activists can actually request permits for their Palestinian counterparts in the West Bank, but that does not break the system of othering. This peace activism in Israel-Palestine is often called co-existence; the idea that two groups should hold hands and get to know each other and it will be fine.

On the other hand there is co-resistance. And that’s also by Israeli and Palestinians struggling together and is based on the idea that this is settler colonialism and apartheid. Their discourse and practices reflect the awareness of the underlying power relations between Palestinians and Israelis. Israelis can go home at the end of the day and lay peacefully in their beds while Palestinian villagers are often raided at night. If a Palestinian is arrested, they can be put in detention for three months without any explanation or compensation. For an Israeli it’s a day. Rather than ignoring such power relations, they use it to build resistance.

A very inspiring example from the West Bank is the Jewish Israelis there who call themselves ‘the Arrestables’. Knowing very well that the consequences of the power relations are different between the Israelis and the Palestinian activists, these Israeli activists jump in front of the Palestinian activists so they can be arrested instead of the Palestinians. These Jewish activists use their privilege with which they can go to court and just get a fine. So the difference between peace activism and non-violent resistance is really that of co-existence versus co-resistance.

Speaking of co-resistance, some feel that the way forward is to build transnational movements and solidarity, that Palestinians can’t do it alone and movements in the US and Europe need to pressure their states, the primary backers of Israel, and work in concert with the Palestinians. How feasible is this?

The international solidarity movement—the path between hope and despair! Which is also where I think the Palestinian struggle is right now. It has never been this blatant, racist movement; the move from Trump to shift the embassy to Jerusalem is a blatant disregard and the media is talking about even Palestinian kids as terrorists. However, I think the international solidarity movement is very promising. It does not replace and should not tell Palestinians what to do. Not at all. It is Palestinians calling for international support. In 2005 they issued a statement of Boycott, Divestment, and Sanction. People ask whether it’s feasible or whether it works. First, we should think about the power nexus behind that point. People study violence, war, and conflict all the time and they’re not asked if it works. Asking only the first question ‘does non-violence work’ or ‘if international protests work’ actually delegitimizes resistance before it even happens. It’s basically a struggle that should receive attention like other ways of struggling.

Secondly, it’s asked whether it’s successful. Well, it’s already there. It may not have succeeded yet but it is constantly succeeding. You see pension funds retreating from Israeli companies. There are protest groups in solidarity with Palestinians. Just last February to April more than 150 universities participated in Israeli apartheid week. They follow the lead of Palestinians in the West Bank and Gaza, not just when an attack happens. You may have seen the world’s convention of people, not so many governments, but people. Also the alternative routes they create. There are many more critical web platforms like The Polis Project who fight for an alternative interpretation of existing knowledge. They don’t tell people what to think but give them the tools to think about situations critically. So you see an anti-normalization campaign. For example, Israel participated in the European song festival (and won it but that’s a different story). But why do we have diplomatic ties and weapons trade with Israel when it’s visibly proven that they use it against a civilian population? Why is there normal trade between the EU and Israel? People are protesting the many million US tax dollars that are poured into Israel each year.

So you can see that from students to divestment movements, a worldwide campaign, at the end of the day, delegitimizes the practices of the Israeli regime in Gaza and West Bank. It’s a very hopeful development, and it’s very much based on a strategic knowledge of non-violent resistance. Not peace activism—let’s talk and hold hands—but rather forcing your pension fund to divest from Israel, forcing universities to not corporate with Israeli universities that are complicit in the occupation. It’s a worldwide movement that takes different shapes in different countries. It is a force to be reckoned with.

There’s been tremendous official backlash against BDS in Europe. In Germany, Frankfurt has outlawed BDS; Berlin and Munich declared it uses the “language of the Nazi era”. In France, BDS activists are tried after a Supreme Court ruling. Even Noam Chomsky said that while he supports BDS, he feels calling for a boycott of Israel will lead to charges of anti-Semitism, that education work has to be done first to make the masses aware. Is BDS losing in Europe?

There has been a lot of pushback against BDS recently, some using the state apparatus to make BDS illegal. It is a scary tactic because it actually undermines the freedom of speech in a democracy and forces us to accept that Israel equals Judaism, which I refuse to accept. However, if you look at it from a scholarly perspective on non-violent resistance, it is actually somewhat promising. Because well, like the saying goes, first they ignore you, then they fight you, and then you win. It is no longer ignored. It wasn’t a force to be reckoned with. It was perceived as something silly, but I think Israel is acutely aware of its power right now.

They set up an entire hasbara machine (meant for positive advertisement of the State). They have also started to feel the pressure from people. There is a vast divide between the ordinary people everywhere and their governments, and I think it’s starting to show by these kinds of oppressive laws. This is not something to not worry about, but it’s part of the process so it should be taken as a victory. They don’t fight you if you’re not successful. So if you look at it from a strategic perspective, it reveals what is really going on underneath the surface.

You also work on, and with, the South African solidarity movement, related to building transnational social justice movements. What’s the reaction of ordinary people is to such initiatives? Some might not be sympathetic to a notion of solidarity since they feel Palestinians in Israel proper don’t face the kind of discrimination they did while the situation of the Palestinians in occupied territories, though abysmal, is not related to apartheid…

That’s an interesting question to answer because not all South Africans think one thing. But in general, like in the Netherlands and UK (the various countries where I worked and lived in the past few years), it is changing. In South Africa, there has been a powerful anti-apartheid movement, and those who were involved in that struggle taught their own children much about power dynamics. Not all people connect Palestine to the situation in South Africa immediately but there are lots of initiatives, for example, last Monday there was a huge tent set up in Cape Town where high-schoolers were invited to watch and discuss the movie Roadmap to Apartheid which looks at how apartheid operated in South Africa and how it is working in Israel-Palestine right now.

So there is a lot of open debate here that I haven’t seen anywhere else in the world as such. It doesn’t mean that they are all for the Palestinian cause but at least there is an open debate on what’s going on, what are crimes against humanity versus crimes against individual people, so there’s much awareness. At the same time the ANC officially supports Palestine but in reality still trades arms with Israel. So how do you make change happen if your government actually agrees? The solidarity activism in the UK or the Netherlands is very different because there is very little knowledge, even though it’s changing, about what is going on in Palestine. Ten or 20 years ago I would’ve had to explain, in an appendix using an entire page, why I used the word “occupation” and how that wasn’t biased.

We should not forget the steps we already made and the knowledge that is readily available. There’s still a lot to do but there’s already a significant change in public opinion. Alternative sources of knowledge are much more widespread right now. I look at high school and university students, not only do they know more about Palestine but they are much more aware of racism in general and of how processes of exclusion like class and gender are intertwined and intersectional. I am quite hopeful. People say it used to be much better in the past but now people, at a much younger age, learn to be critical of the power structures around them.

It is not there yet but it is almost inevitable that at one point, just like segregation in the US and the apartheid, they will crumble. Perhaps that president at the time will say they were always against the occupation; that’s what you heard after the end of apartheid. It was the companies, the business, and the governments that folded last, it was the people first. And most people are already there or at least majority of the people realize what they’ve known about Israel-Palestine is not as straightforward as they thought. Following the developments will be fascinating. The recent days were very desperate, but if you look at people on the ground, there is a reason to be hopeful.

In the end, I want to ask, how do you see the situation unfolding in the near future and, in the longer term, your hopes for the future of the Palestinian people, given both the grim reality and the hopeful prospects you described.

I am a scientist, not in the business of predicting an uncertain future. That said, there are certain developments, movements some of which we have talked about, that will inevitably shape the future of Palestinians and Israelis. Looking at these, I am again caught between hope and despair. In the short term there is more despair because the bombing of Gaza, the implementation of even more racist laws in Israel, and the clampdown on BDS are examples of the continued dehumanization of Palestine. The current state of international affairs do not give me any hope of an intervention either; public opinion in Israel (exceptions are there of course) certainly points towards even more violent interventions, perhaps even an all out military attack on Gaza or the West Bank.

In the longer term, don’t forget there are simply too many activities, too many chapters, too many different groups, and too many different locations to stop the human rights solidarity movement or the civil base of resistance on the ground. You can suppress, imprison, or kill a person but you cannot kill a movement. One only has to look at history to see large-scale human right violations and dehumanization cannot be sustained. Apartheid collapsed, segregation ended, slavery abolished; long term but certainly within my lifetime this human rights struggle, this civil resistance will succeed.

‘Palestine civil resistance will succeed, for you can kill a person, not a movement’—a conversation with Anne de Jong

With a military manpower of 3,600,000 and defense budget of $20 billion for a population almost as small as that of the city of Amsterdam, Israel has one of the most advanced armies in the world. Their nuclear arsenal is estimated to possess at least 80 warheads, at par with India and Pakistan. Israel’s Missile Defense System is a multi-tier architecture that includes the Arrow to intercept long-range ballistic missiles, David’s sling to intercept medium range rockets and, the Iron Dome. All of these use highly sophisticated technology that can not only detect and track missiles from as far away as 300 miles but also have the capability to determine where the incoming projectile will land. The Israeli military can remotely operate Guardium robots (Umanned Ground Vehicles) equipped with sensor cameras and weapons, deployed on the border with Syria and Gaza strip, to safely avoid any physical contact with opposing forces.

Now consider the Palestinians – they have no air force and no navy; no tanks and no missiles. Only 50 armored vehicles (nearly all in the West Bank) and offensive ground forces of 62,200 people. Most of their rockets are homemade that are incapable of inflicting mass civilian casualties. Norman Finklestein quotes a counter intelligence veteran of the U.S. CIA who spent his career monitoring Israeli and Palestinian military capabilities: “Hamas’ rockets can kill people and they have, but compared to what the Israelis are using, the Palestinians are firing bottle rockets.” On top of this, the Israeli state practices a near total control not only on the movement of goods and people but also on the natural resources available to the landlocked Palestinian population. A third of the population has no access to electricity, and water is limited to 60-90 liters per person per day while some are forced to survive on 10-20 liters per day. A study conducted on the Israeli-Palestinian Joint Water Committee by the University of Sussex reveals a relation so asymmetrical the author deems it inappropriate to classify it as an instance of international water ‘cooperation’ since Israel practically ‘dominates’ all ground and surface water resources.

Comparing Israel, with all its military might and overwhelming Western support, and the Palestinians, prisoners in their own land, humiliated and helpless, one is left perplexed at the dominant media and scholarly narrative on their ‘conflict’. Why is the prism from which this issue viewed so skewed? Given the lopsided power dynamic, can the issue ever be resolved? To shed light on these questions and to delve deeper into the nature of the relationship between Israel and Palestine, we talk to Dr. Anna De Jong.

Anne de Jong is a political anthropologist and activist. She has extensively studied civil resistance in the Middle East. During her research in the occupied territories of Palestine, she noticed the propensity of academia to view Israel and Palestine as two equal entities fighting for peace—a concept she realized was far from accurate. Anne has dedicated her work to right this false dichotomy by exposing the unequal power relations between the two. In this interview for The Polis Project with Sara Azeem, she discusses her research on the Zionist hegemony and forms of violence and their effect on the Palestinian colonial struggle. Currently based in South Africa, de Jong is looking at international solidarity activism towards Palestine and the role of outside pressure, mainly from the Boycott, Divestment, Sanctions movement.

Sara Azeem: There are conflicts all around, what about the Middle East made it attractive for your study?

Anne de Jong: Well, first I think was the complete shock that everything you knew about a particular area was wrong. I considered myself a critical, open-minded student already but when I went there, it was so different. So completely different in every aspect that I just couldn’t stop wondering how that came about. Part of that is, as I write in some of my articles, the idea that conflict has two sides, as is the everyday experience of living in a Palestinian town, its culture. And everything you had previously learned was so opposite to reality that it really drew my attention. It is one of the most horrific injustices and it’s ongoing. I am an academic/activist or activist/academic and I think it is impossible to disconnect the universities—the academy—and knowledge from power and politics in the world around us. It should not be disconnected, like on one side there is the academy and on the other the society that we study. It [academy] is part of how we look at life and how we make policy and how materials are distributed and how we view the world around us. Given this, if you encounter a situation so unjust, I believe, to not write about it is almost being complicit.

Could you share a moment, or an example, to elaborate on this?

One that I encountered immediately was the idea that there is an Israel and there is a Palestine. People think that there is an Israel and next to it there is a Palestine and they are fighting each other. And when you get there, you see there is no simple dichotomy, no binary distinction, not geographically, not demographically, not ideologically. Geographically the region that we know as Israel and Occupied Palestine Territories including Gaza and East Jerusalem is all under Israeli control one way or another. There is no Palestinian entity but rather the Bantustans of apartheid South Africa. Israel never set their outer borders. If you cross the 1967 Green Line (border), there’s no sign, you wouldn’t even notice it. You go in and out of it without noticing any distinction between the Israel where Israelis live and the Palestine where Palestinians live. This is because 1.5 million Israeli citizens are Palestinians and more than 500,000 Israeli settlers live in the West Bank. So that rigid, binary distinction just holds no reflection of the reality on the ground.

How important do you think is the lens from which to view the conflict? To many westerners it is a story of intransigent conflict while others argue it is a colonial struggle…

It is very hard to avoid even in my own language but I try to challenge the idea that there is such a thing as the Israel-Palestine “conflict”. I looked at what I call the peace and conflict paradigm—the assumption of two sides with the desired solution of peace between them—and I object to this paradigm that is seen as “objective” or “neutral”. It is actually a very biased paradigm with far-reaching consequences.

Geographically you have Gaza, which is besieged; in Israel proper, there is institutionalized discrimination; then there is Jerusalem where there is apartheid; and West Bank is militarily occupied. So there are no two sides, let alone countries.

Calling it a ‘conflict’ really sanitizes, even legitimizes, very unequal power relations. On one hand is Israel, the country that has the fourth most powerful army in the world, and on the other are a scattered, dispossessed people who struggle for freedom, self-determination, and even basic human rights such as freedom of movement. So there are no two sides or two equal sides. It also obscures the idea of peace and conflict. Presenting it as a ‘conflict between two sides’ obscures what it is in fact: a classic human rights struggle.So, it is not about Israel on one side and Palestine on the other. It’s also not about Jews on one side and Muslims on the other, or even Israel versus the Arabs. It is a conflict between those who agree or yield to Zionist exceptionalism and believe that fundamental human rights and civil rights depend on one’s ethnonationalism.

Israel is a democracy for its Jewish citizens, that’s absolutely true—they have the right to vote, the right to water and basic facilities, and they can go to a judge or the police if they need to. This is not so for Palestinians on the West Bank or Gaza or even for Palestinian citizens of Israel because those rights are dependent on your ethnonationalism, on whether you are Jewish or not. So the whole peace and conflict paradigm basically obscures the fact that it’s between those who agree with Zionist ethnonationalism and those who say well, hold on, human rights should apply to all.

In your work, you argue for an emphasis on the knowledge-making process and revival of subjugated knowledge to understand what you call the ‘cacophony of the Palestinian experience’. Could you elaborate?

I wanted to ask some questions: How did we come to think of conflict as a neutral term? And what are the origins of how we came to think about the ‘Israel-Palestine conflict’ in terms of ‘conflict’ and how it became normal and objective. So I conducted research in the genealogy of conflict. Genealogy is a methodology, which stems from looking at the power behind knowledge. As Foucault, who followed Nietzsche, said, genealogy looks at the force relations behind the interpretations of history—how we came to look at history the way we do, how we speak and think, the possibilities of thinking about situations, how they came about, how it all gets normalized…I did archival research on when people started to speak about Israel-Palestine in terms of conflict, specifically looking at early Zionist writings and correspondence. I found it was actually not at all a spontaneous process but rather a very consciously advocated Zionist strategy that they discussed among themselves and consciously applied to counter accusations of settler colonialism.

Look at it in the context of that time: in late 19th century when political Zionist movement came about, settler colonialism was not yet condemned the way we do now. It was a legitimate enterprise. Jewish people at that time in opposition to pogroms, for example in Russia, decided there needed to be a national movement to create a State and they chose to do so in Palestine. But they were met with resistance not only from the Palestinians who said ‘hold on, we’re already here’ but also from Jewish leaders and authorities in the West because they believed that Judaism is not about a nation-state as Zionism, it is about the Torah. Early on, the Zionist movement was opposed by Jewish religious leaders like Rabbi Samson Raphael Hirsch (1808 – 1888), who rightfully observed at the time that there was a move from being Jewish because of what you believe, the Torah, to being Jewish because of what you are, an ethnic connection.Once the Zionist movement had made some success and started the immigrant stream to Palestine, the opposition grew with Zionists particularly accused of settler colonialism.

To counter this, Ben Gurion, a known Zionist, said ‘well, we need to broaden this framework; they are looking at us like we are colonialists imposing ourselves on an indigenous population, so we broaden the framework and make it about us, the Jewish, small, persecuted nation returning to our land versus a big aggressive Arab Goliath’. He said we should not ever speak about the Zionist movement and the Palestinians. Instead, we should talk about a peaceful Jewish David versus the aggressive Arab Goliath.

It changed the power dynamics. First, it became about “return” rather than colonial settlement. Second, Zionists denied Palestinians their specific national identity—who lived there before documented time—and merged them with a broader Arab entity, disconnected from their land. Third, they created the binary opposition as a small Zionist nation defending themselves rather than a settler colonial oppressor. This indeed become central to the Zionist discourse and myth not only to oppose Palestinians but also establish a Zionist base where not all Jews were immediately Zionist. Early on, it was very easy for a Jewish person to say ‘I am not a part of the Zionist movement, I am a Jew, and I am part of this synagogue’. Later, it became a lot harder to say ‘I am not a citizen’ or ‘I am not a part of this [Zionism]’.Finally, the myth became widely accepted as reality, gaining support from America and the United Kingdom (who recognized the state immediately).So if you speak out when there is a dichotomy such as this it makes you choose sides. By saying ‘I am against settler colonialism’ (which is what Israel is) you’re anti-Semitic because they merged the settler colonial movement with Judaism.

Could you talk more about how the Zionist movement played the underdog and how it gathered support internationally?

I don’t think the early Zionist movement considered itself the underdog; they very consciously portrayed it. Look at its early writings, they were very well aware of dispossessing an entire people and some even said ‘yes, regretfully but if you want Jewish majority then you have to use means necessary’. Letters between early Zionist leaders characterizes this; they discussed the force they meant to use and how they’d legitimize it for the rest of the world.So the myth turned into reality for a lot of people. You can prove and clearly make a case that this is not what happened but still for a lot of people it holds true. For many it became a really emotional matter. The Jewish diaspora grew up with a powerful propaganda machine about Israelis constantly under threat and how they are about to be pushed in the sea. But in reality Israel is the one who oppresses Palestinians. They talk about rockets from Gaza as threats but those “rockets” are homemade devices that cannot even be adequately directed to hit the targets. They have no tanks, helicopters, or soldiers who could actually combat—there is no army on the other side. There is no threat.

Internationally, one needs to understand two other support groups. One, there are many religious Zionists, not Jewish but Christian, who believe from a Biblical perspective that the Middle East is the place of return of the Messiah and they believe for the Messiah to return it has to be inhabited by Zionists. Second, we must acknowledge there is a lot of guilt about the Holocaust, as there should be. Europe was complicit with Nazi Germany. While we celebrate resistance and blame it all on the Nazis, the fact is that most European countries, for example the Netherlands, willingly extradited their Jewish population. The resistance was only from underground groups; it did not come from the State so there should be guilt about that.At the same time, the Palestinians were not the ones who created the Holocaust. It is not okay to say that because of the Holocaust in Europe, Israel and Jewish people now have the right to oppress another people. But these are the dynamics that play internationally. It is an interesting time because many of those groups and beliefs are shaking and trembling right now.

It is interesting you mentioned that and I am going to come back to this after a slight detour. You talked about revising your belief of not mixing an anthropological study with activism, how at first you avoided that but later events changed your mind and chose to function as an activist while carrying out scholarly work. Could you share a bit more about that transition.

From primary school, through high school and university you learn that academic knowledge is neutral and should be objective. Like anyone else I believed that. However, if you look at the world around, you see how it is shaped by academic knowledge; that knowledge helps us make sense of the world, so the knowledge doesn’t exist in isolation. I have asthma, I have inhalers lying around everywhere. I think of the time in Gaza visiting a friend from the years of my research. Her 12-year-old daughter died from an asthma attack because Israel wasn’t allowing medicine into Gaza. How do you work with this? How is it objective to not mention that sorrow, that pain? How is it possible to objectively describe this on one side and Israel on the other? How should I look at both experiences? Is it not scientifically more transparent and legitimate if I portray and stand for my research findings, which show very unequal power relations, that there is injustice, and it is entirely against human rights?

Academic knowledge has consequences so I might as well be aware of those, and of the power and privilege I have as an academic to influence the world around me. I am incredibly lucky that I could travel to Gaza (not anymore), but I could go to Palestine. The next logical step is to use that power and privilege and to write for the subaltern, for those denied a voice. That gradually turned into not just observing activism and resistance that I was studying but also actively placing myself as part of how the world is constructed around us. I no longer wanted to be a part of the silent majority, and I tried to use my position, knowledge, and skills. Particularly for me it came around in 2010 when a large part of my research group decided to organize a Freedom Flotilla to break the siege at Gaza.Those boats were attacked, ten people were killed, we were detained, it was very bloody, and horrific, but it did break the silence on the siege around Gaza. Before that people didn’t know that it was a very small piece of land—completely surrounded by air, sea, and land—controlled by Israel. But after this there was no turning back and it only deepened my commitment to being an activist/academic. I decided my knowledge shouldn’t be confined to libraries but should help the people that I study.

You mentioned in one of your articles that Freedom Flotilla was a microcosm of the events unfolding for the Palestinians—people were captured while news was controlled by Israel. There are parallels between what is happening now—the Grand March Home. Could you place in context how this latest series of protests by the Palestinians is yet another act of peaceful resistance by a hapless people which doesn’t get highlighted as it should.

Well it’s been desperate and heartbreaking, but also positive and hopeful. It may sound strange looking at the extreme violence and deaths but I’ll explain. On one hand, it is desperate to see that a non-violent, mass protest calls upon Palestinians’ 70 years of expulsion from their land. They planned a six-week protest to claim their (internationally acknowledged) right to return. Their houses, their homes, their villages, places they were expelled from because of the 1948 Nakba (Israeli independence) are there, less than 60 miles from Jerusalem. They protest in a non-violent manner, there are no politicians, people go to the border, and they’re horrifically shot at from a distance, not even close to a “clash”. There isn’t one Israeli hurt yet the media talked about “confrontations”.

And this civil population is asking for its right not just to return but also to live in Gaza where the situation is untenable. There are only up to four hours of electricity a day, most water resources are extremely polluted, more than 40% are unemployed, they cannot leave the Gaza strip without permission from Israel.Women especially are hit hard. There’s not enough cancer treatment for breast cancer. So they are completely controlled by Israel and locked in what people call open-air prison but I say these people are not even convicted of doing anything wrong. It is like a holding cell; people protest, and get shot down. So this notion of “clashes” completely ignores the underlying power relations. It portrays Palestinians as aggressive and attacking Israel or threatening the border of Israel when there is no border. Israel refuses to state their borders because they control all the land between the sea and the river.

Then it is portrayed as a struggle between Hamas and Israel. Again, there is no such thing as a Palestinian state. Yes, Hamas is elected in the Gaza strip and Hamas was elected once upon a time, many years ago, in the West, but that completely ignores the fact that Palestinians don’t have self-determination. Hamas cannot issue a passport with which Palestinians from the Gaza strip can go about.What is interesting, and hopeful, is the dynamics are changing. They don’t allow international journalists into Gaza but with cell phones and social media the horrific images can no longer be buried under Israeli state propaganda. It exposes the unequal power relations, and it relates to people around the world who go ‘this is like gunning down of black activists in America during segregation’. I think this change is fascinating, and significant.

This brings us back to where you mentioned international support, the guilt in Europe about the Jewish extradition, and how that’s changing a bit now…

It’s very interesting. In the UK and Netherlands, the government just adopted a new definition of anti-Semitism that includes criticizing Israel. Not only does this silence political violence on an entire group of people, it is an infringement on free speech and actually equates Jewish people all around the world with Israel. These are scary developments in Europe. What’s positive is more and more Jewish people are getting vocal that it is not in their name, that it’s not what their idea, feeling, or connection with Israel is or with what Judaism means. I find that hopeful. Also what is important is in the international solidarity movement more Jewish people are speaking up because they can actually break this myth that somehow Israel speaks for all Jewish people in the world. The idea that Israel speaks for all the Jewish people in the world is anti-Semitic. Also, there is a compelling dynamic because there is now a growing group of very critical Israeli as well as international Jews who work with Palestinians and who are aware of the power mechanism. They don’t want to speak over the Palestinians but they have a voice that is heard, so they use that to give a platform to Palestinian activists in Gaza and the West Bank.

You mentioned power and resistance as an area of expertise in everyday life. Some feel resistance can’t always be peaceful. Even Mandela realized he couldn’t bring about victory through peaceful means. How can resistance work in the face of a ruthless, or lunatic (per Norman Finkelstein) Israel?

The idea that non-violent resistance is always peaceful as opposed to violent resistance is based on a couple of misunderstandings. We should think of peace activism on one hand and non-violence on the other. That’s a distinction I will come back to. But first, non-violent resistance is not holding hands and loving your enemy, it’s also not a strategy based on appealing to the heart of the oppressor. It is a strategy based on an analysis of power relations. If you look at any oppressive regime, it is not a massive, almighty monster that comes out of nowhere. On the contrary, power is always dynamic. It is never complete in that there is one side that holds all the power. You can imagine it as a house model with the roof as the oppressive regime, like the Israeli state over Palestine. That roof does not just exist; it depends on pillars of support and different pillars execute their power. A dictator who doesn’t have an army can shout all he wants but he doesn’t have the power to execute.

Then there are other pillars like the media, the military apparatus, tax collecting institutions, sanctions, imprisonment, or the near to complete monopoly on violence. Now, non-violent resistance doesn’t say ‘hey, I’m human please give me my freedom’. What it does is it attacks those pillars of support; it attacks the idea that Israel is a legitimate state. For example, them shooting down unarmed protestors shakes the idea that Israel is legitimate. It attacks the pillar of the media. So it is a strategy to very consciously break down the pillars of support so that the rooftop collapses.

You can see it in the case of Milosevic. I prefer a more recent example because Gandhi and Martin Luther King were just two. Erica Chenoweth wrote a book, Why Civil Resistance Works, and it shows that it actually works better than violent uprisings. If you attack those pillars of support to collapse the house, then there are 189 different actions ranging from boycott to protest. You can put them roughly into three categories: there is direct action, like this demonstration in Gaza right now but there is also civil disobedience, and that is where people no longer comply with this regime. For example, they refuse to pay tax, or they refuse to join the Israeli military as conscientious objectors. The third one is to build alternative routes, which is also a form of resistance because it makes the population less dependent on their oppressor. A part of that can also be the reconstruction of Palestinian homes or finding alternative media outlets around the world as you see them springing up.

So, social change happens through non-violence not because the person decides that he loves you all of a sudden. It’s either by conversion—they become convinced that they need to stop their oppressive practices—or most of the time it’s accommodation—they have to or they are forced to accept that they cannot sustain a regime. Or what would happen in the case of Israel-Palestine is that they will be forced to let go even though they don’t want to. It’s what you saw in former Yugoslavia when Milosevic gave his troops the order to shoot. The troops were standing in front of the population and were given the orders to shoot, but the police didn’t do it. He, one of the most ruthless dictators of the past 20 years, couldn’t get his orders executed because nobody listened to him anymore and his power collapsed.

If you look at non-violence as resistance, as opposed to peace activism, you see that it’s not the opposite of violent resistance. Palestine has the right, under international law, to resist an occupation in any way. It can’t be seen in opposition to violence because violence is everywhere, in any possible manner, imposed on the Palestinians. The non-violence that you see in Gaza right now does not come from a belief that there should be peace at all times. I believe they realize that violence is not the only way. It is not an alternative to violent resistance but a different strategy, one in which everybody can partake.

Then there is also an important distinction I want to make between non-violent resistance and peace activism. It’s often confused and equated with each other. Peace activism is often based on pity, or on the belief that, for example, bombing by Israel was too much. This does not break the peace and conflict paradigm. It still very much works with the Zionist idea of Israel-Palestine, so it propagates talking and dialogue between the two sides. What it really does is reproduce the unequal power relations and does not go to the heart of the problem. It just states that there are two narratives, two victims, and both are rightfully upset, which reproduces existing power relations.

For example, there are many Jewish-Israeli peace organizations like Peace Now who say ‘well the blockade is too strict’. They don’t say the blockade is unfair. You can even see the reproduction of those power relations in the decisions within that activism. The Israeli activists can actually request permits for their Palestinian counterparts in the West Bank, but that does not break the system of othering. This peace activism in Israel-Palestine is often called co-existence; the idea that two groups should hold hands and get to know each other and it will be fine.

On the other hand there is co-resistance. And that’s also by Israeli and Palestinians struggling together and is based on the idea that this is settler colonialism and apartheid. Their discourse and practices reflect the awareness of the underlying power relations between Palestinians and Israelis. Israelis can go home at the end of the day and lay peacefully in their beds while Palestinian villagers are often raided at night. If a Palestinian is arrested, they can be put in detention for three months without any explanation or compensation. For an Israeli it’s a day. Rather than ignoring such power relations, they use it to build resistance.

A very inspiring example from the West Bank is the Jewish Israelis there who call themselves ‘the Arrestables’. Knowing very well that the consequences of the power relations are different between the Israelis and the Palestinian activists, these Israeli activists jump in front of the Palestinian activists so they can be arrested instead of the Palestinians. These Jewish activists use their privilege with which they can go to court and just get a fine. So the difference between peace activism and non-violent resistance is really that of co-existence versus co-resistance.

Speaking of co-resistance, some feel that the way forward is to build transnational movements and solidarity, that Palestinians can’t do it alone and movements in the US and Europe need to pressure their states, the primary backers of Israel, and work in concert with the Palestinians. How feasible is this?

The international solidarity movement—the path between hope and despair! Which is also where I think the Palestinian struggle is right now. It has never been this blatant, racist movement; the move from Trump to shift the embassy to Jerusalem is a blatant disregard and the media is talking about even Palestinian kids as terrorists. However, I think the international solidarity movement is very promising. It does not replace and should not tell Palestinians what to do. Not at all. It is Palestinians calling for international support. In 2005 they issued a statement of Boycott, Divestment, and Sanction. People ask whether it’s feasible or whether it works. First, we should think about the power nexus behind that point. People study violence, war, and conflict all the time and they’re not asked if it works. Asking only the first question ‘does non-violence work’ or ‘if international protests work’ actually delegitimizes resistance before it even happens. It’s basically a struggle that should receive attention like other ways of struggling.

Secondly, it’s asked whether it’s successful. Well, it’s already there. It may not have succeeded yet but it is constantly succeeding. You see pension funds retreating from Israeli companies. There are protest groups in solidarity with Palestinians. Just last February to April more than 150 universities participated in Israeli apartheid week. They follow the lead of Palestinians in the West Bank and Gaza, not just when an attack happens. You may have seen the world’s convention of people, not so many governments, but people. Also the alternative routes they create. There are many more critical web platforms like The Polis Project who fight for an alternative interpretation of existing knowledge. They don’t tell people what to think but give them the tools to think about situations critically. So you see an anti-normalization campaign. For example, Israel participated in the European song festival (and won it but that’s a different story). But why do we have diplomatic ties and weapons trade with Israel when it’s visibly proven that they use it against a civilian population? Why is there normal trade between the EU and Israel? People are protesting the many million US tax dollars that are poured into Israel each year.

So you can see that from students to divestment movements, a worldwide campaign, at the end of the day, delegitimizes the practices of the Israeli regime in Gaza and West Bank. It’s a very hopeful development, and it’s very much based on a strategic knowledge of non-violent resistance. Not peace activism—let’s talk and hold hands—but rather forcing your pension fund to divest from Israel, forcing universities to not corporate with Israeli universities that are complicit in the occupation. It’s a worldwide movement that takes different shapes in different countries. It is a force to be reckoned with.

There’s been tremendous official backlash against BDS in Europe. In Germany, Frankfurt has outlawed BDS; Berlin and Munich declared it uses the “language of the Nazi era”. In France, BDS activists are tried after a Supreme Court ruling. Even Noam Chomsky said that while he supports BDS, he feels calling for a boycott of Israel will lead to charges of anti-Semitism, that education work has to be done first to make the masses aware. Is BDS losing in Europe?

There has been a lot of pushback against BDS recently, some using the state apparatus to make BDS illegal. It is a scary tactic because it actually undermines the freedom of speech in a democracy and forces us to accept that Israel equals Judaism, which I refuse to accept. However, if you look at it from a scholarly perspective on non-violent resistance, it is actually somewhat promising. Because well, like the saying goes, first they ignore you, then they fight you, and then you win. It is no longer ignored. It wasn’t a force to be reckoned with. It was perceived as something silly, but I think Israel is acutely aware of its power right now.

They set up an entire hasbara machine (meant for positive advertisement of the State). They have also started to feel the pressure from people. There is a vast divide between the ordinary people everywhere and their governments, and I think it’s starting to show by these kinds of oppressive laws. This is not something to not worry about, but it’s part of the process so it should be taken as a victory. They don’t fight you if you’re not successful. So if you look at it from a strategic perspective, it reveals what is really going on underneath the surface.

You also work on, and with, the South African solidarity movement, related to building transnational social justice movements. What’s the reaction of ordinary people is to such initiatives? Some might not be sympathetic to a notion of solidarity since they feel Palestinians in Israel proper don’t face the kind of discrimination they did while the situation of the Palestinians in occupied territories, though abysmal, is not related to apartheid…

That’s an interesting question to answer because not all South Africans think one thing. But in general, like in the Netherlands and UK (the various countries where I worked and lived in the past few years), it is changing. In South Africa, there has been a powerful anti-apartheid movement, and those who were involved in that struggle taught their own children much about power dynamics. Not all people connect Palestine to the situation in South Africa immediately but there are lots of initiatives, for example, last Monday there was a huge tent set up in Cape Town where high-schoolers were invited to watch and discuss the movie Roadmap to Apartheid which looks at how apartheid operated in South Africa and how it is working in Israel-Palestine right now.

So there is a lot of open debate here that I haven’t seen anywhere else in the world as such. It doesn’t mean that they are all for the Palestinian cause but at least there is an open debate on what’s going on, what are crimes against humanity versus crimes against individual people, so there’s much awareness. At the same time the ANC officially supports Palestine but in reality still trades arms with Israel. So how do you make change happen if your government actually agrees? The solidarity activism in the UK or the Netherlands is very different because there is very little knowledge, even though it’s changing, about what is going on in Palestine. Ten or 20 years ago I would’ve had to explain, in an appendix using an entire page, why I used the word “occupation” and how that wasn’t biased.

We should not forget the steps we already made and the knowledge that is readily available. There’s still a lot to do but there’s already a significant change in public opinion. Alternative sources of knowledge are much more widespread right now. I look at high school and university students, not only do they know more about Palestine but they are much more aware of racism in general and of how processes of exclusion like class and gender are intertwined and intersectional. I am quite hopeful. People say it used to be much better in the past but now people, at a much younger age, learn to be critical of the power structures around them.

It is not there yet but it is almost inevitable that at one point, just like segregation in the US and the apartheid, they will crumble. Perhaps that president at the time will say they were always against the occupation; that’s what you heard after the end of apartheid. It was the companies, the business, and the governments that folded last, it was the people first. And most people are already there or at least majority of the people realize what they’ve known about Israel-Palestine is not as straightforward as they thought. Following the developments will be fascinating. The recent days were very desperate, but if you look at people on the ground, there is a reason to be hopeful.

In the end, I want to ask, how do you see the situation unfolding in the near future and, in the longer term, your hopes for the future of the Palestinian people, given both the grim reality and the hopeful prospects you described.

I am a scientist, not in the business of predicting an uncertain future. That said, there are certain developments, movements some of which we have talked about, that will inevitably shape the future of Palestinians and Israelis. Looking at these, I am again caught between hope and despair. In the short term there is more despair because the bombing of Gaza, the implementation of even more racist laws in Israel, and the clampdown on BDS are examples of the continued dehumanization of Palestine. The current state of international affairs do not give me any hope of an intervention either; public opinion in Israel (exceptions are there of course) certainly points towards even more violent interventions, perhaps even an all out military attack on Gaza or the West Bank.

In the longer term, don’t forget there are simply too many activities, too many chapters, too many different groups, and too many different locations to stop the human rights solidarity movement or the civil base of resistance on the ground. You can suppress, imprison, or kill a person but you cannot kill a movement. One only has to look at history to see large-scale human right violations and dehumanization cannot be sustained. Apartheid collapsed, segregation ended, slavery abolished; long term but certainly within my lifetime this human rights struggle, this civil resistance will succeed.

SUPPORT US

We like bringing the stories that don’t get told to you. For that, we need your support. However small, we would appreciate it.