Every year from March to June, the media reports harrowing news of heatwaves, stories of suffering and survival saturating the headlines. By August, the urgency wanes, the language shifts to general updates, and soon, these calamities fade from the collective memory. The cycle repeats with cruel predictability. The next year, another heatwave, more deaths, yet we never address the crucial questions: how did we reach this point? Why do these tragedies recur with such relentless regularity? And how do we better adapt and mitigate these direct consequences of climate change?

During this year’s heatwave, India recorded a staggering 374 heat stroke deaths and over 67,000 suspected cases between March and July, according to health ministry data stated in the Lok Sabha last month. Data submitted by the ministry of earth sciences paints a more troubling picture, noting that since 2013, barring some exceptions, India has seen over a thousand heat stroke deaths every year. The government’s own data documents over 24,000 heat-wave deaths between 1992 and 2015, despite serious concerns about the under-documenting of heat-related deaths. The climate crisis is also expected to result in heat waves coming earlier, staying longer, and becoming more frequent, exacerbated in turn by urban heat island effects.

In Down to Earth: Politics in the New Climatic Regime, Bruno Latour speaks of the need for a conceptual shift that dissolves the boundaries between nature and politics. Latour contends that our traditional political doctrines are woefully inadequate for confronting the sprawling, complex realities of the climate crisis, especially as it wreaks havoc on post-colonial territories. This reality calls for a radical rethinking of our political and economic systems, a restructuring that acknowledges the intricate web of climate change and global inequality. But the Indian government’s response, centering primarily around its Heat Action Plans, has not reflected the radical rethinking that the climate emergency demands.

Over the recent years of heat waves, questions about the government’s response have repeatedly been posed in parliament. Each time, the government acknowledges the crisis. “The trend in heatwave conditions across the country has been analysed by the India Meteorological Department (IMD) based on datasets from 1961 to 2020,” the earth sciences ministry stated on 7 August. “In general, there is an increasing trend in the frequency of heatwaves in the heat core zone covering northern plains and central India. The rising frequency and intensity of heat waves are clear indicators of the broader issue of global climate change.” The IMD defines heatwaves differently based on geographical classifications, marked by temperatures over 40°C in the plains, 37°C in the coasts and over 30°C in the hills. In December last year, the ministry noted that across the last 50 years, India typically witnessed “4-8 days of heat wave conditions,” but in March–June 2023, regions such as West Bengal and Bihar endured over 30 days of it.

In its submissions in parliament about measures taken, the union government emphasises the Heat Action Plans. The HAPs are advisory documents prepared by the Indian Meteorological Department in collaboration with the state governments and the National Disaster Management Authority (NDMA). The key strategies of HAPs include establishing an early-warning system by forecasting heat waves; building capacity of healthcare professionals and infrastructure to deal with heat-related emergencies; public awareness and community outreach programmes; and inter-agency cooperation and collaboration with civil society organisations. The union government is working with 23 heat-prone states and over 130 cities and districts to develop and implement HAPs across the country. However, assessments of the HAPs have found that they are inadequately supported—financially, legally, and institutionally—for them to prove effective against the escalating health and climate crisis.

In 2023, the Centre for Policy Research published a comprehensive study of 37 HAPs across the country, and identified key shortcomings that require urgent attention. In its recommendations, the study noted that the HAPs were poor at identifying vulnerable groups—with only two of 37 HAPs conducting vulnerability assessments—leading to a lack of information for targeted distribution of scarce resources. Even when the recognition of vulnerability is found, the report added, it did not necessarily translate to implementation measures that sought to address it. It also observed that HAPs did not seem to have any solid legal foundation, which created inefficiencies and shortcomings in their functioning, and led to allowed a lack of transparency and accessibility of their data.

Positively, the report found, the HAPs included a diverse set of proposals, including long-term strategies that could reduce heat for more than one season, including recommendations for infrastructural solutions, capacity building and nature-based measures. However, the study also found that the HAPs were vastly underfunded to implement this—with only three of the 37 examined identifying funding for any of the listed measures, despite their far-reaching recommendations. The study proposed linking them to national climate funding mechanisms and adding heatwaves to list of notified disasters in order for HAPs to gain access to additional funding.

Yet, in August this year, the earth sciences ministry stated that the 15th Finance Commission—which proposed recommendations on fiscal matters for the period of 2021-2026—had considered the inclusion and deemed it unnecessary. According to the ministry’s statement in parliament, the commission observed “that the list of notified disasters eligible for funding from the State Disaster Response Mitigation Fund (SDRMF) and National Disaster Response Mitigation Fund (NDRMF) covers the needs of the State to a large extent and thus did not find much merit in the request to expand its scope.”

The HAPs reflects an unfortunate lack of political will to put in place the necessary institutional and financial support needed for the policies needed to combat the brutal heat waves. It shows that the recurring deaths every year is not a result of lack of scientific understanding or for shortage of policy recommendations, but due to political inaction.

On 19 June this year, the health ministry released a set of guidelines for navigating the “Heat Wave Season 2024.” The ministry directed for measures such as the dissemination of NDMA guidelines and implementation of heat action plans. It also instructed senior officials to ensure hospitals are fully prepared to provide optimal healthcare, and noted other measures such as establishing special heatwave units in central government hospitals; and for hospitals to stockpile ORS packs, essential medicines, cooling apparatus, and drinking water. The guidelines noted that coordination with electricity companies is crucial to guarantee an uninterrupted power supply, and calls for the enactment of steps to mitigate indoor heat without delay.

However, in addition to the institutional and financial hurdles for the implementation of these measures, the guidelines also reveal a one-dimensional approach to heatwaves. A more holistic approach would take into account the stark realities of unemployment, food security, and nutrition in India, and how heat waves are intrinsically tied to it.

Rising temperatures and malnutrition are silent, insidious killers. Evidence suggests that scorching heat escalates the incidence of diseases like diarrhea, which is responsible for 13% of the deaths of children under five—an estimated 300,000 infants each year in India. Studies show that heat during pregnancy correlates with lower birth weights, while higher temperatures fuel illnesses such as diarrhea, fever, and cough, devastating infant health.

In their research paper, “Heat, Infant Mortality, and Adaptation: Evidence from India,” Rakesh Banerjee and Riddhi Maharaj explore how an economic system reliant on agriculture and marked by income instability exacerbates climate-related mortality. In India, a large portion of the population depends on the unpredictable nature of agriculture for their livelihoods. Extreme heat ravages crop yields, forcing farmers and laborers into struggles of dwindling incomes. This economic shock strikes hardest during the post-monsoon season, when food reserves run dry, labor demand plummets, and food prices soar.

Research has shown that high temperatures during the crop-growing season significantly reduce agricultural yields for major crops such as rice, bajra, cotton, soybean, groundnut, and jowar. Extreme heat also affects real wages in rural areas, which in turn results in a surge in malnutrition and illness among pregnant women and infants. The system’s inability to cushion these blows, paired with scant access to adaptive investments and technology, deepens the vulnerability of these communities to climate-induced health crises. Yet, as the analysis of the HAPs have shown, the Indian response to the heat waves has fallen woefully short in identifying vulnerable groups who require targeted interventions.

Public investment in health infrastructure and income-support programmes are paramount to addressing these multifaceted consequences of heat waves. Such investments can counteract the lethal effects of extreme heat on infant mortality. Initiatives such as the National Rural Employment Guarantee Act and the Accredited Social Health Activists emerge as lifelines. NREGA offers employment that stabilises income, enabling rural households to sustain food intake and access vital health services during harsh weather. ASHA workers play a pivotal role, improving maternal and infant health by promoting prenatal and postnatal care and providing immediate treatment for heat-related ailments.

In the 2024-25, despite a 2.5 percent increase in the budget for the Ministry of Women and Child Development, the allocation for the Saksham Anganwadi and POSHAN 2.0 initiatives were dropped to Rs 21,200 crore from Rs 21,523 crore in 2023-2024. It is worth noting that the initiatives constitute the majority of funds for the Ministry of Women and Child Development, at 81% of its total estimated expenditure. However, since ICDS and Anganwadi services have been grouped under Saksham Anganwadi and POSHAN 2.0, it remains unclear how much funding is specifically designated for ICDS.

Moreover, Anganwadi centres continue to suffer from poor infrastructure, vacancies and low remunerations, so the cut in their funding—even as minimal as two percent—is a step in the wrong direction. ASHA and Anganwadi workers are now included under the Ayushman Bharat – Pradhan Mantri Jan Arogya Yojana (PMJAY), but the PMJAY’s budget only saw a small rise from Rs 6,800 crore in 2023-2024 to Rs 7,300 crore in 2024-2025, leaving unclear how much ASHA workers specifically received.

The allocation for MGNREGA remains unchanged at Rs 86,000 crore in 2024-2025, the same as in 2023-2024. However, the budget for food subsidies has been reduced from Rs 2,12,332 crore in 2023-2024 to Rs 2,05,250 crore in 2024-2025. Similarly, funding for the Pradhan Mantri Garib Kalyan Anna Yojana (PMGKAY) dropped from Rs 2,12,332 crore in 2023-2024 to Rs 2,05,250 crore in 2024-2025.

The Pradhan Mantri Kisan Samman Nidhi (PM-KISAN) scheme, which was introduced in the 2019 interim budget to support Small and Marginal Farmers (SMFs) with financial assistance for crop inputs, has not seen any increase in allocation this year. Economists argue that the Rs 6,000 cash transfer under PM-KISAN is insufficient to meaningfully improve farmers’ incomes or reduce debt, especially as it has not been adjusted for inflation. Additionally, the programme excludes tenant farmers, focusing only on landowners.

What was necessary was for the union budget to have allocated more and comprehensive funds to directly support the Heat Action Plans on the one hand, and to combat the multifaceted impact by supporting health, food security, agriculture, and employment programmes, such as MGNREGA and ICDS, on the other. Instead, we see soaring allocations for the power sector, tax cuts for corporations, and exemptions for critical minerals mining—policies that fuel climate change and environmental degradation. Meanwhile, the government’s lofty ambitions of crafting a new climate taxonomy for sustainable investments seem hollow. What vanishes in this sleight of hand is budgetary transparency, resulting instead in the illusion of increased funding as a mirage conjured by creative accounting rather than genuine financial commitment.

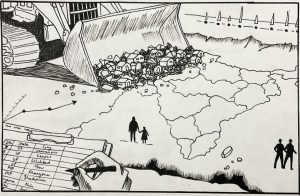

Neoliberal economic policies exacerbate inequalities. These policies prioritise market growth over social welfare, neglecting critical public investments in health, food security, and climate resilience. Globalisation has widened the chasm of inequality, casting a particularly long shadow over post-colonial nations like India. These countries, once plundered for their riches under the guise of colonialism, now find themselves ensnared in the ruthless machinery of global capitalism. The spoils of environmental degradation and resource extraction are seldom shared with those who bear the brunt. Instead, the remnants of colonial exploitation have left these nations with fragile political and economic frameworks, unable to withstand the battering waves of globalization and climate change. Rising sea levels, cyclones, and the relentless erosion of biodiversity are not mere natural events—they are harbingers of economic despair. Post-colonial countries like India are shackled by the chains of their colonial past, their lands and peoples bearing the brunt of a legacy that refuses to die.

Related Posts

Why the heatwave deaths in India should not be forgotten after the summer

Every year from March to June, the media reports harrowing news of heatwaves, stories of suffering and survival saturating the headlines. By August, the urgency wanes, the language shifts to general updates, and soon, these calamities fade from the collective memory. The cycle repeats with cruel predictability. The next year, another heatwave, more deaths, yet we never address the crucial questions: how did we reach this point? Why do these tragedies recur with such relentless regularity? And how do we better adapt and mitigate these direct consequences of climate change?

During this year’s heatwave, India recorded a staggering 374 heat stroke deaths and over 67,000 suspected cases between March and July, according to health ministry data stated in the Lok Sabha last month. Data submitted by the ministry of earth sciences paints a more troubling picture, noting that since 2013, barring some exceptions, India has seen over a thousand heat stroke deaths every year. The government’s own data documents over 24,000 heat-wave deaths between 1992 and 2015, despite serious concerns about the under-documenting of heat-related deaths. The climate crisis is also expected to result in heat waves coming earlier, staying longer, and becoming more frequent, exacerbated in turn by urban heat island effects.

In Down to Earth: Politics in the New Climatic Regime, Bruno Latour speaks of the need for a conceptual shift that dissolves the boundaries between nature and politics. Latour contends that our traditional political doctrines are woefully inadequate for confronting the sprawling, complex realities of the climate crisis, especially as it wreaks havoc on post-colonial territories. This reality calls for a radical rethinking of our political and economic systems, a restructuring that acknowledges the intricate web of climate change and global inequality. But the Indian government’s response, centering primarily around its Heat Action Plans, has not reflected the radical rethinking that the climate emergency demands.

Over the recent years of heat waves, questions about the government’s response have repeatedly been posed in parliament. Each time, the government acknowledges the crisis. “The trend in heatwave conditions across the country has been analysed by the India Meteorological Department (IMD) based on datasets from 1961 to 2020,” the earth sciences ministry stated on 7 August. “In general, there is an increasing trend in the frequency of heatwaves in the heat core zone covering northern plains and central India. The rising frequency and intensity of heat waves are clear indicators of the broader issue of global climate change.” The IMD defines heatwaves differently based on geographical classifications, marked by temperatures over 40°C in the plains, 37°C in the coasts and over 30°C in the hills. In December last year, the ministry noted that across the last 50 years, India typically witnessed “4-8 days of heat wave conditions,” but in March–June 2023, regions such as West Bengal and Bihar endured over 30 days of it.

In its submissions in parliament about measures taken, the union government emphasises the Heat Action Plans. The HAPs are advisory documents prepared by the Indian Meteorological Department in collaboration with the state governments and the National Disaster Management Authority (NDMA). The key strategies of HAPs include establishing an early-warning system by forecasting heat waves; building capacity of healthcare professionals and infrastructure to deal with heat-related emergencies; public awareness and community outreach programmes; and inter-agency cooperation and collaboration with civil society organisations. The union government is working with 23 heat-prone states and over 130 cities and districts to develop and implement HAPs across the country. However, assessments of the HAPs have found that they are inadequately supported—financially, legally, and institutionally—for them to prove effective against the escalating health and climate crisis.

In 2023, the Centre for Policy Research published a comprehensive study of 37 HAPs across the country, and identified key shortcomings that require urgent attention. In its recommendations, the study noted that the HAPs were poor at identifying vulnerable groups—with only two of 37 HAPs conducting vulnerability assessments—leading to a lack of information for targeted distribution of scarce resources. Even when the recognition of vulnerability is found, the report added, it did not necessarily translate to implementation measures that sought to address it. It also observed that HAPs did not seem to have any solid legal foundation, which created inefficiencies and shortcomings in their functioning, and led to allowed a lack of transparency and accessibility of their data.

Positively, the report found, the HAPs included a diverse set of proposals, including long-term strategies that could reduce heat for more than one season, including recommendations for infrastructural solutions, capacity building and nature-based measures. However, the study also found that the HAPs were vastly underfunded to implement this—with only three of the 37 examined identifying funding for any of the listed measures, despite their far-reaching recommendations. The study proposed linking them to national climate funding mechanisms and adding heatwaves to list of notified disasters in order for HAPs to gain access to additional funding.

Yet, in August this year, the earth sciences ministry stated that the 15th Finance Commission—which proposed recommendations on fiscal matters for the period of 2021-2026—had considered the inclusion and deemed it unnecessary. According to the ministry’s statement in parliament, the commission observed “that the list of notified disasters eligible for funding from the State Disaster Response Mitigation Fund (SDRMF) and National Disaster Response Mitigation Fund (NDRMF) covers the needs of the State to a large extent and thus did not find much merit in the request to expand its scope.”

The HAPs reflects an unfortunate lack of political will to put in place the necessary institutional and financial support needed for the policies needed to combat the brutal heat waves. It shows that the recurring deaths every year is not a result of lack of scientific understanding or for shortage of policy recommendations, but due to political inaction.

On 19 June this year, the health ministry released a set of guidelines for navigating the “Heat Wave Season 2024.” The ministry directed for measures such as the dissemination of NDMA guidelines and implementation of heat action plans. It also instructed senior officials to ensure hospitals are fully prepared to provide optimal healthcare, and noted other measures such as establishing special heatwave units in central government hospitals; and for hospitals to stockpile ORS packs, essential medicines, cooling apparatus, and drinking water. The guidelines noted that coordination with electricity companies is crucial to guarantee an uninterrupted power supply, and calls for the enactment of steps to mitigate indoor heat without delay.

However, in addition to the institutional and financial hurdles for the implementation of these measures, the guidelines also reveal a one-dimensional approach to heatwaves. A more holistic approach would take into account the stark realities of unemployment, food security, and nutrition in India, and how heat waves are intrinsically tied to it.

Rising temperatures and malnutrition are silent, insidious killers. Evidence suggests that scorching heat escalates the incidence of diseases like diarrhea, which is responsible for 13% of the deaths of children under five—an estimated 300,000 infants each year in India. Studies show that heat during pregnancy correlates with lower birth weights, while higher temperatures fuel illnesses such as diarrhea, fever, and cough, devastating infant health.

In their research paper, “Heat, Infant Mortality, and Adaptation: Evidence from India,” Rakesh Banerjee and Riddhi Maharaj explore how an economic system reliant on agriculture and marked by income instability exacerbates climate-related mortality. In India, a large portion of the population depends on the unpredictable nature of agriculture for their livelihoods. Extreme heat ravages crop yields, forcing farmers and laborers into struggles of dwindling incomes. This economic shock strikes hardest during the post-monsoon season, when food reserves run dry, labor demand plummets, and food prices soar.

Research has shown that high temperatures during the crop-growing season significantly reduce agricultural yields for major crops such as rice, bajra, cotton, soybean, groundnut, and jowar. Extreme heat also affects real wages in rural areas, which in turn results in a surge in malnutrition and illness among pregnant women and infants. The system’s inability to cushion these blows, paired with scant access to adaptive investments and technology, deepens the vulnerability of these communities to climate-induced health crises. Yet, as the analysis of the HAPs have shown, the Indian response to the heat waves has fallen woefully short in identifying vulnerable groups who require targeted interventions.

Public investment in health infrastructure and income-support programmes are paramount to addressing these multifaceted consequences of heat waves. Such investments can counteract the lethal effects of extreme heat on infant mortality. Initiatives such as the National Rural Employment Guarantee Act and the Accredited Social Health Activists emerge as lifelines. NREGA offers employment that stabilises income, enabling rural households to sustain food intake and access vital health services during harsh weather. ASHA workers play a pivotal role, improving maternal and infant health by promoting prenatal and postnatal care and providing immediate treatment for heat-related ailments.

In the 2024-25, despite a 2.5 percent increase in the budget for the Ministry of Women and Child Development, the allocation for the Saksham Anganwadi and POSHAN 2.0 initiatives were dropped to Rs 21,200 crore from Rs 21,523 crore in 2023-2024. It is worth noting that the initiatives constitute the majority of funds for the Ministry of Women and Child Development, at 81% of its total estimated expenditure. However, since ICDS and Anganwadi services have been grouped under Saksham Anganwadi and POSHAN 2.0, it remains unclear how much funding is specifically designated for ICDS.

Moreover, Anganwadi centres continue to suffer from poor infrastructure, vacancies and low remunerations, so the cut in their funding—even as minimal as two percent—is a step in the wrong direction. ASHA and Anganwadi workers are now included under the Ayushman Bharat – Pradhan Mantri Jan Arogya Yojana (PMJAY), but the PMJAY’s budget only saw a small rise from Rs 6,800 crore in 2023-2024 to Rs 7,300 crore in 2024-2025, leaving unclear how much ASHA workers specifically received.

The allocation for MGNREGA remains unchanged at Rs 86,000 crore in 2024-2025, the same as in 2023-2024. However, the budget for food subsidies has been reduced from Rs 2,12,332 crore in 2023-2024 to Rs 2,05,250 crore in 2024-2025. Similarly, funding for the Pradhan Mantri Garib Kalyan Anna Yojana (PMGKAY) dropped from Rs 2,12,332 crore in 2023-2024 to Rs 2,05,250 crore in 2024-2025.

The Pradhan Mantri Kisan Samman Nidhi (PM-KISAN) scheme, which was introduced in the 2019 interim budget to support Small and Marginal Farmers (SMFs) with financial assistance for crop inputs, has not seen any increase in allocation this year. Economists argue that the Rs 6,000 cash transfer under PM-KISAN is insufficient to meaningfully improve farmers’ incomes or reduce debt, especially as it has not been adjusted for inflation. Additionally, the programme excludes tenant farmers, focusing only on landowners.

What was necessary was for the union budget to have allocated more and comprehensive funds to directly support the Heat Action Plans on the one hand, and to combat the multifaceted impact by supporting health, food security, agriculture, and employment programmes, such as MGNREGA and ICDS, on the other. Instead, we see soaring allocations for the power sector, tax cuts for corporations, and exemptions for critical minerals mining—policies that fuel climate change and environmental degradation. Meanwhile, the government’s lofty ambitions of crafting a new climate taxonomy for sustainable investments seem hollow. What vanishes in this sleight of hand is budgetary transparency, resulting instead in the illusion of increased funding as a mirage conjured by creative accounting rather than genuine financial commitment.

Neoliberal economic policies exacerbate inequalities. These policies prioritise market growth over social welfare, neglecting critical public investments in health, food security, and climate resilience. Globalisation has widened the chasm of inequality, casting a particularly long shadow over post-colonial nations like India. These countries, once plundered for their riches under the guise of colonialism, now find themselves ensnared in the ruthless machinery of global capitalism. The spoils of environmental degradation and resource extraction are seldom shared with those who bear the brunt. Instead, the remnants of colonial exploitation have left these nations with fragile political and economic frameworks, unable to withstand the battering waves of globalization and climate change. Rising sea levels, cyclones, and the relentless erosion of biodiversity are not mere natural events—they are harbingers of economic despair. Post-colonial countries like India are shackled by the chains of their colonial past, their lands and peoples bearing the brunt of a legacy that refuses to die.

SUPPORT US

We like bringing the stories that don’t get told to you. For that, we need your support. However small, we would appreciate it.