When Mohammad Bilal’s house was demolished with his family still inside

The city of Saharanpur, in northwest Uttar Pradesh, is famous for its wooden craftsmanship. In Khatakheri, a neighbourhood where the streets are narrow and lined with wood workshops, the sound of chisels and saws fill the air. But on 11 June 2022, a very different and ominous sound took over, striking fear in the hearts of its residents.

That month, Saharanpur was gripped by unrest amid protests against inflammatory remarks against the prophet Mohammed made by Nupur Sharma, who was the national spokesperson of the Bhartiya Janata Party at the time. The previous day, hundreds of Muslim protesters had conducted demonstrations across cities in Uttar Pradesh calling for Sharma’s arrest, and the state administration responded with violence. Two years later, the residents of Saharanpur seemed unable to remember the exact events of the day. There were different stories running through their collective memory.

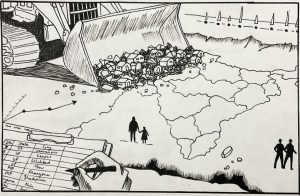

What they remember clearly is the palpable tension prevailing across different neighborhoods of the city. “Bohot dar ka mahaul hogaya tha”—There was an atmosphere of fear, one resident recalled. There were whispers of communal riots breaking out in the city. It is now known that those whispers were fearmongering rumours. But the false rumours had very real repercussions on several lives, and the homes in which they were lived. Many homes were demolished in the terror of “bulldozer justice” that ensued, and with these houses, the memories that formed their foundation and the futures to be built on top of them fell to rubble as well. This is the story of the house of Mohammad Bilal, the lives lived in it, and those cut short by its demolition. Bilal was the only member of his family who agreed to be identified by name.

Thirty years ago, when Bilal was a young man struggling to make ends meet, he bought a small house of three rooms in Khatakheri. It was a modest beginning. His eldest son was just five or six at the time, and Bilal and his wife dreamt of creating a home that would provide security and stability for their growing family. Bilal ran a small tea shop along with his brother, barely earning enough to cover their needs, but every spare rupee was put towards the house. Slowly, they built it up, expanding from a single-story to a two-story home that could accommodate their sons as well as their future families. The two eldest sons eventually started a small hosiery business, operating out of their home in Khatakheri, which helped bring in extra income.

“Hamne apni puri zindagi laga di iss makan ko ghar banane me”— Our entire lives have gone in transforming this from a house into a home—Bilal said, each sentence punctuated by contemplative pauses. “Kaise-kaise karke ek ghar khareed pae. Kitne saal hogae yahan; har kona, har diwar, sab pariwar ka hissa hai.” (Somehow, with some work or the other, we were able to buy a house. It’s been so many years here; every corner, every wall, it is all a part of the family.)

Walking towards Bilal’s house, the street is thick with the scent of fresh wood and the fine dust that settles on everything. For Bilal and his wife, their home represented years of hard work and sacrifice. They bought and built it up piece by piece, over three decades. It was a place in which they put tremendous effort to be able to call it their own, where they raised their six sons and welcomed their grandchildren.

Saharanpur has always been a city of contrast, diverse in its cultures and religions who coexist peacefully, but also prone to tension and unrest. For families like Bilal’s, who have always tried to keep their heads down and stay out of trouble, these periods of unrest brought fear and uncertainty. “Bach na chahiye, jahan tak bhi ho admi bache”—You have to be safe, as far as possible, you have to save yourself—said Bilal, in a tone that suggested that the wisdom of hindsight had become a cautionary warning for the future. “Agar kahi jhagda horaha hota hai, mai to vahan khada bhi nahi hota, bilkul bhi bheed me nahi khada hota. Ab to photo dekh kar karwahi horahi, mujrim ya jurm se matlab nahi hai, photo aana chahiye.” (If there’s a fight happening somewhere, I don’t even stand there, I don’t stand among the crowds at all. Now investigations are conducted based on photographs, never mind the crime and the criminal, it’s the photo that matters.)

According to news reports, after the Friday prayers of 10 June at Saharanpur’s Jama Masjid, a group of young Muslim men marched towards the local clock tower demanding the arrest of Nupur Sharma, started pelting stones, and clashed with the police. However, Babar Mudassir, a lawyer representing some of the men arrested following the incident, accused the police of misrepresenting the events of the day. He said there was no organised procession, or planned protest, as projected by the police “This is the state’s version that there was a protest,” Mudassir said. “The Jama Masjid is a big mosque. Every Friday, hundreds of people come there to offer namaz there. The local police wanted to show that Muslims are getting agitated and want to protest. They wanted to heat-up the situation and they made this into a big thing.” He added that there was a spontaneous protest among the congregation as they left the Jama Masjid, which was met by a large police contingent and locals stationed in the area who provoked the Muslim protesters.

Rumours of violence at the clock tower area spread quickly and reached Khatakheri. Like everyone else in the neighbourhood, Bilal’s wife immediately began fearing whatever would come next upon hearing the speculation of the clashes. She didn’t have to wonder long. The next day, the constant noise of wood workshops that usually filled their narrow lane was instead replaced by the boots and lathis of police officers storming down their streets. The woodworkers of the neighbourhood recalled how they quickly shut the workshops and went inside. At the time, Bilal’s elder sons were out working, leaving his wife in the house with their youngest son, her daughters-in-law, and their children. Bilal was at his tea shop, unaware of the turmoil that would unfold at home.

Without warning, at 2pm that day, the police forced their way into their house and dragged the youngest son, 19 years old at the time, out into the street. The women inside were left in a state of shock, terrified and unsure of what would happen next. Bilal’s wife recalled running after her son, but the police took him away. She said that there were no female officers present when the police entered their house, and the family was not even allowed time to cover their heads.

“Uss wakt ka to bohot bura manzar tha ji, kya batave, bohot tagdi pareshani aayi thi bayan nahi karsakte aisa manzar tha”—It was a really difficult time, what can I even say, we were so troubled that I can’t even tell you how bad it was—Bilal said. He added, with pain in his voice, “Sugar ka to aise hi mareez hu mai. jab maine sunna, mere to pair tale zameen nikal gai”—I’m already diabetic, and when I heard about that day, the ground below my feet gave way.

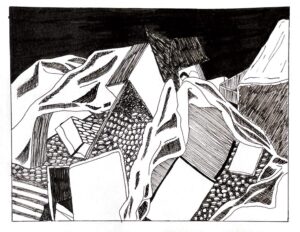

It wasn’t long before the dreaded sound of a bulldozer echoed through the streets. The machine rumbled down the thin lane, its massive claw poised to strike. Inside the house, the women of Bilal’s family were huddled together in a back room on the first floor, clutching their children closely. They were terrified, with no idea how much of the house would be destroyed, and whether they would even be allowed to leave; they were not. But they also did not want to, they recalled.

Bilal’s daughter-in-law showed me the room they sat in when the bulldozer struck. “We didn’t even know about it,” the eldest son said. “Our neighbours told us that he has been taken by the police and that they are bringing a bulldozer.” He added, “They didn’t tell us anything, they didn’t show us any document, they just used the bulldozer directly. We didn’t even know how much they were going to demolish. We didn’t understand anything at the time.”

The bulldozer struck the front wall of the house with a deafening crash, sending bricks and debris tumbling to the ground. Their home, which had stood strong for thirty years, shook under the force of the attack. The women described feeling paralysed with fear, their hearts pounding as they waited for the next blow. For Bilal’s wife, the experience was extremely traumatising. Even now, two years later, she still jumps at the sound of a sudden knock on the door. “Ammi bohot bimar hoagain, kitna ilaaj chalraha, vo hadse se bahar hi nahi aapayi”—My mother has been really sick since then, and despite all the ongoing treatment, she has not been able to get out of that trauma—said Bilal’s second-eldest son, who is 35-years-old. “She has not been able to recover to her former self.”

Bilal added, “Pata nahi kitni bimariya iske baad lag gai hamko, jo pehle nahi thi”—We’ve suffered from so many health conditions after the incident, ones we never had before. “Kisi bhi baat se tension hojae. Zara si baat par tension hojae. Ghabrahat chahe jab hojae.” (We get high blood pressure at the all sorts of things. We become extremely tense about the smallest things. An anxiety takes over us.)

The demolition was partial—the bulldozer tore down a section of the front wall before the police called it off. But the damage was done. The house, that became a home over a period of thirty years, a symbol of the family’s hard work and perseverance, was now a scarring reminder of the violence that had been visited upon them. “Bas ye hai ki kayamat toot gai thi, pareshani to choti si ho, ye to Bohot tagdi pareshani thi, ye to ek kayamat tooti thi humpe”—It was as if doomsday had fallen upon us, even a small problem can be troubling, but this was a massive one, like a catastrophe had struck us. Bilal said. “Koi nahi aaya unke aage. Police ke aage kaun aaega, aur bulldozer ke aage kaun aaega? Aas-pados to bohot badiya hai hamare, lekin aise wakt me police ke saamne kaun aaega.” (Nobody stood in front of them. Who will stand in front of the police, in front of a bulldozer? Our neighbours are great people, but at a time like this, who will stand in front of the police.)

According to the lawyer Mudassir, “The bulldozer action was only to send out a message—they later showed a section of the house to be illegal in a back-dated notice.” He added that they then also sent notices of demolition to all the people named in the first-information reports registered on 10 June. Bilal ridiculed the lack of judicial process. “Phir to adalato ko band kardo”—Then shut down the courts, he said. “Agar bulldozer hi jurm ka hal hai toh adalate kyo khol rakhi hai? Adalat ka matlab hai jurm sabit sabit karna, ye mujrim hai ya bekasoor hai, bulldozer hal thodi hai jurm ka.” (If the bulldozer is the solution to crimes, then why have courts been set up? The purpose of the court is to confirm the commission of a crime, of guilt and innocence, a bulldozer is not the solution.)

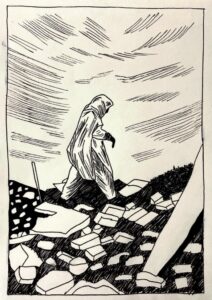

Their house now stands as a testament to the family’s suffering. The green chalk-painted walls now bear the marks of the day that shattered not just the structure of the house, but also the family’s sense of security. The psychological impact on the family continues to be profound. The members, who once found comfort within the walls of their house, now live in constant fear, always on edge, always bracing for the worst.

Despite the trauma, Bilal and his family have tried to move on. They patched up the wall as best as they could, using whatever materials they could afford. Life continues, as it must. Bilal still runs his tea shop, his eldest sons continue their hosiery business, their children go to school, young enough to keep laughing and offer the family a vital reminder that not everything has been lost. “Ye to bas Allah ki madad thi ki nuksan kam hua”—It is only with Allah’s aid that the damage was minimal—Bilal said. “Aur Allah hi aage bhi madad karta rahega. Hisab kharab hogaya tha mera, Allah ne hi reham kiya.” (And Allah will continue to help in the future as well. My situation had become difficult, but it was Allah who showed mercy.)

Related Posts

When Mohammad Bilal’s house was demolished with his family still inside

The city of Saharanpur, in northwest Uttar Pradesh, is famous for its wooden craftsmanship. In Khatakheri, a neighbourhood where the streets are narrow and lined with wood workshops, the sound of chisels and saws fill the air. But on 11 June 2022, a very different and ominous sound took over, striking fear in the hearts of its residents.

That month, Saharanpur was gripped by unrest amid protests against inflammatory remarks against the prophet Mohammed made by Nupur Sharma, who was the national spokesperson of the Bhartiya Janata Party at the time. The previous day, hundreds of Muslim protesters had conducted demonstrations across cities in Uttar Pradesh calling for Sharma’s arrest, and the state administration responded with violence. Two years later, the residents of Saharanpur seemed unable to remember the exact events of the day. There were different stories running through their collective memory.

What they remember clearly is the palpable tension prevailing across different neighborhoods of the city. “Bohot dar ka mahaul hogaya tha”—There was an atmosphere of fear, one resident recalled. There were whispers of communal riots breaking out in the city. It is now known that those whispers were fearmongering rumours. But the false rumours had very real repercussions on several lives, and the homes in which they were lived. Many homes were demolished in the terror of “bulldozer justice” that ensued, and with these houses, the memories that formed their foundation and the futures to be built on top of them fell to rubble as well. This is the story of the house of Mohammad Bilal, the lives lived in it, and those cut short by its demolition. Bilal was the only member of his family who agreed to be identified by name.

Thirty years ago, when Bilal was a young man struggling to make ends meet, he bought a small house of three rooms in Khatakheri. It was a modest beginning. His eldest son was just five or six at the time, and Bilal and his wife dreamt of creating a home that would provide security and stability for their growing family. Bilal ran a small tea shop along with his brother, barely earning enough to cover their needs, but every spare rupee was put towards the house. Slowly, they built it up, expanding from a single-story to a two-story home that could accommodate their sons as well as their future families. The two eldest sons eventually started a small hosiery business, operating out of their home in Khatakheri, which helped bring in extra income.

“Hamne apni puri zindagi laga di iss makan ko ghar banane me”— Our entire lives have gone in transforming this from a house into a home—Bilal said, each sentence punctuated by contemplative pauses. “Kaise-kaise karke ek ghar khareed pae. Kitne saal hogae yahan; har kona, har diwar, sab pariwar ka hissa hai.” (Somehow, with some work or the other, we were able to buy a house. It’s been so many years here; every corner, every wall, it is all a part of the family.)

Walking towards Bilal’s house, the street is thick with the scent of fresh wood and the fine dust that settles on everything. For Bilal and his wife, their home represented years of hard work and sacrifice. They bought and built it up piece by piece, over three decades. It was a place in which they put tremendous effort to be able to call it their own, where they raised their six sons and welcomed their grandchildren.

Saharanpur has always been a city of contrast, diverse in its cultures and religions who coexist peacefully, but also prone to tension and unrest. For families like Bilal’s, who have always tried to keep their heads down and stay out of trouble, these periods of unrest brought fear and uncertainty. “Bach na chahiye, jahan tak bhi ho admi bache”—You have to be safe, as far as possible, you have to save yourself—said Bilal, in a tone that suggested that the wisdom of hindsight had become a cautionary warning for the future. “Agar kahi jhagda horaha hota hai, mai to vahan khada bhi nahi hota, bilkul bhi bheed me nahi khada hota. Ab to photo dekh kar karwahi horahi, mujrim ya jurm se matlab nahi hai, photo aana chahiye.” (If there’s a fight happening somewhere, I don’t even stand there, I don’t stand among the crowds at all. Now investigations are conducted based on photographs, never mind the crime and the criminal, it’s the photo that matters.)

According to news reports, after the Friday prayers of 10 June at Saharanpur’s Jama Masjid, a group of young Muslim men marched towards the local clock tower demanding the arrest of Nupur Sharma, started pelting stones, and clashed with the police. However, Babar Mudassir, a lawyer representing some of the men arrested following the incident, accused the police of misrepresenting the events of the day. He said there was no organised procession, or planned protest, as projected by the police “This is the state’s version that there was a protest,” Mudassir said. “The Jama Masjid is a big mosque. Every Friday, hundreds of people come there to offer namaz there. The local police wanted to show that Muslims are getting agitated and want to protest. They wanted to heat-up the situation and they made this into a big thing.” He added that there was a spontaneous protest among the congregation as they left the Jama Masjid, which was met by a large police contingent and locals stationed in the area who provoked the Muslim protesters.

Rumours of violence at the clock tower area spread quickly and reached Khatakheri. Like everyone else in the neighbourhood, Bilal’s wife immediately began fearing whatever would come next upon hearing the speculation of the clashes. She didn’t have to wonder long. The next day, the constant noise of wood workshops that usually filled their narrow lane was instead replaced by the boots and lathis of police officers storming down their streets. The woodworkers of the neighbourhood recalled how they quickly shut the workshops and went inside. At the time, Bilal’s elder sons were out working, leaving his wife in the house with their youngest son, her daughters-in-law, and their children. Bilal was at his tea shop, unaware of the turmoil that would unfold at home.

Without warning, at 2pm that day, the police forced their way into their house and dragged the youngest son, 19 years old at the time, out into the street. The women inside were left in a state of shock, terrified and unsure of what would happen next. Bilal’s wife recalled running after her son, but the police took him away. She said that there were no female officers present when the police entered their house, and the family was not even allowed time to cover their heads.

“Uss wakt ka to bohot bura manzar tha ji, kya batave, bohot tagdi pareshani aayi thi bayan nahi karsakte aisa manzar tha”—It was a really difficult time, what can I even say, we were so troubled that I can’t even tell you how bad it was—Bilal said. He added, with pain in his voice, “Sugar ka to aise hi mareez hu mai. jab maine sunna, mere to pair tale zameen nikal gai”—I’m already diabetic, and when I heard about that day, the ground below my feet gave way.

It wasn’t long before the dreaded sound of a bulldozer echoed through the streets. The machine rumbled down the thin lane, its massive claw poised to strike. Inside the house, the women of Bilal’s family were huddled together in a back room on the first floor, clutching their children closely. They were terrified, with no idea how much of the house would be destroyed, and whether they would even be allowed to leave; they were not. But they also did not want to, they recalled.

Bilal’s daughter-in-law showed me the room they sat in when the bulldozer struck. “We didn’t even know about it,” the eldest son said. “Our neighbours told us that he has been taken by the police and that they are bringing a bulldozer.” He added, “They didn’t tell us anything, they didn’t show us any document, they just used the bulldozer directly. We didn’t even know how much they were going to demolish. We didn’t understand anything at the time.”

The bulldozer struck the front wall of the house with a deafening crash, sending bricks and debris tumbling to the ground. Their home, which had stood strong for thirty years, shook under the force of the attack. The women described feeling paralysed with fear, their hearts pounding as they waited for the next blow. For Bilal’s wife, the experience was extremely traumatising. Even now, two years later, she still jumps at the sound of a sudden knock on the door. “Ammi bohot bimar hoagain, kitna ilaaj chalraha, vo hadse se bahar hi nahi aapayi”—My mother has been really sick since then, and despite all the ongoing treatment, she has not been able to get out of that trauma—said Bilal’s second-eldest son, who is 35-years-old. “She has not been able to recover to her former self.”

Bilal added, “Pata nahi kitni bimariya iske baad lag gai hamko, jo pehle nahi thi”—We’ve suffered from so many health conditions after the incident, ones we never had before. “Kisi bhi baat se tension hojae. Zara si baat par tension hojae. Ghabrahat chahe jab hojae.” (We get high blood pressure at the all sorts of things. We become extremely tense about the smallest things. An anxiety takes over us.)

The demolition was partial—the bulldozer tore down a section of the front wall before the police called it off. But the damage was done. The house, that became a home over a period of thirty years, a symbol of the family’s hard work and perseverance, was now a scarring reminder of the violence that had been visited upon them. “Bas ye hai ki kayamat toot gai thi, pareshani to choti si ho, ye to Bohot tagdi pareshani thi, ye to ek kayamat tooti thi humpe”—It was as if doomsday had fallen upon us, even a small problem can be troubling, but this was a massive one, like a catastrophe had struck us. Bilal said. “Koi nahi aaya unke aage. Police ke aage kaun aaega, aur bulldozer ke aage kaun aaega? Aas-pados to bohot badiya hai hamare, lekin aise wakt me police ke saamne kaun aaega.” (Nobody stood in front of them. Who will stand in front of the police, in front of a bulldozer? Our neighbours are great people, but at a time like this, who will stand in front of the police.)

According to the lawyer Mudassir, “The bulldozer action was only to send out a message—they later showed a section of the house to be illegal in a back-dated notice.” He added that they then also sent notices of demolition to all the people named in the first-information reports registered on 10 June. Bilal ridiculed the lack of judicial process. “Phir to adalato ko band kardo”—Then shut down the courts, he said. “Agar bulldozer hi jurm ka hal hai toh adalate kyo khol rakhi hai? Adalat ka matlab hai jurm sabit sabit karna, ye mujrim hai ya bekasoor hai, bulldozer hal thodi hai jurm ka.” (If the bulldozer is the solution to crimes, then why have courts been set up? The purpose of the court is to confirm the commission of a crime, of guilt and innocence, a bulldozer is not the solution.)

Their house now stands as a testament to the family’s suffering. The green chalk-painted walls now bear the marks of the day that shattered not just the structure of the house, but also the family’s sense of security. The psychological impact on the family continues to be profound. The members, who once found comfort within the walls of their house, now live in constant fear, always on edge, always bracing for the worst.

Despite the trauma, Bilal and his family have tried to move on. They patched up the wall as best as they could, using whatever materials they could afford. Life continues, as it must. Bilal still runs his tea shop, his eldest sons continue their hosiery business, their children go to school, young enough to keep laughing and offer the family a vital reminder that not everything has been lost. “Ye to bas Allah ki madad thi ki nuksan kam hua”—It is only with Allah’s aid that the damage was minimal—Bilal said. “Aur Allah hi aage bhi madad karta rahega. Hisab kharab hogaya tha mera, Allah ne hi reham kiya.” (And Allah will continue to help in the future as well. My situation had become difficult, but it was Allah who showed mercy.)

SUPPORT US

We like bringing the stories that don’t get told to you. For that, we need your support. However small, we would appreciate it.