The relentless rise of civilian killings in Bastar under Chhattisgarh’s new BJP government

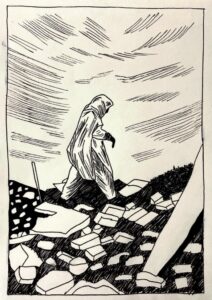

On the first day of 2024, a six-month-old girl, Mangli, was shot dead by Indian security forces in Bastar. The bullet went through Maase Sodi’s hand, who was holding her daughter at the time, cutting through her fingers before it killed the infant girl. The death was the first of dozens in the region this year, which has been marked by a surge in operations by security forces. While the state and central governments have made proud declarations about the number of Maoists killed in these encounters, Adivasi locals have repeatedly contested these claims, and accused the security forces of killing civilians.

In the case of Mangli’s death, too, government, police and paramilitary officials claimed that the six-month-old died during a crossfire with Maoists. But eyewitness accounts belie the official version. In a detailed investigation for Article 14, Malini Subramaniam reported that Sodi and other locals had assembled in the village of Mutvendi, in Bijapur district, to protest against a road-construction project. The administration was constructing a road that would connect the remote village to Gangaloor, a key junction in the district, 21 kilometres away. The construction would destroy important trees for the locals, including a mango and salfi tree essential for Sodi and others, and the villagers had gathered in a peaceful protest to save their trees. Eyewitnesses told Subramaniam that the police and paramilitary forces randomly started firing at them, killing Mangli in the process.

The six-month-old’s death was the prologue to a number of civilian killings in Chhattisgarh’s Bastar division, which comprises the seven districts of Bastar, Bijapur, Dantewada, Kanker, Kodagaon, Narayanpur and Sukma. As of 30 May, security forces have reportedly killed 118 Maoists in the region, but according to locals and activists, many of them were civilians.

On 20 January, two teenage girls, Nagi Punem and Soni Madkam, and 40-year-old Kosa Karam, a father of five, were among a group of eight Adivasis from Bijapur’s Nendra village, travelling to Gorna village to join a protest against the killing of Mangli. En route, the social activist Bela Bhatia said, security forces began firing at the group, killing the three of them immediately and detaining and beating the other five in the group, which included other teenagers as well as ten-year-old Chottu Podiam. Bhatia recounted these details after speaking to four members of the group who were subsequently released, including Jimme Uika, who bore witness to the hour-long gunfire that took the lives of the three villagers. The state police, however, claimed to have killed three Maoists.

On 27 January, Podiya Mandavi, a farmer and father of four from Pedka village, died in police custody. Mandavi had been detained by the police, accused of involvement in a Maoist Improvised Explosive Device (IED) attack from April last year, which had killed ten security personnel and a driver. While police officials claimed that Mandavi “suddenly died of a stroke,” his body reportedly bore knife scars that suggested custodial torture. Despite the efforts of the activist Soni Sori and Mandavi’s kin to seek justice, the police refused to register a first information report concerning his death.

On 30 January, in Bhairamgarh tehsil near the Indravati river, 22-year-old farmer Ramesh Oyam was killed. According to his brother-in-law, Payko Kunjam, Oyam was shot by security forces while he was bathing in the river. According to the Article 14 report, the local superintendent of police acknowledged the civilian casualty but refuted any police involvement. Oyam was not affiliated with any political party nor the People’s Liberation Guerrilla Army (PLGA)—the armed wing of the Communist Party of India (Maoists)—and was killed the day after the birth of his child.

On 2 February, Piso Kovasi and Kanharu Duru, residents of Gomagal village in Narayanpur, were ambushed and killed by security forces. According to Piso’s uncle, Kume Kovasi, his nephew had gone to the nearby forest with three others to drink sulphi, a traditional drink extracted from trees, when they came under fire. The police have reportedly refused to register complaints by Kume and other villagers, and accused the two of being Maoists from whom they’ve recovered two weapons—claims that the locals refute.

On 27 March, the police reported that six Maoists had been killed in a gunfight in the forest near Bijapur’s Chikurbhatti and Pusbaka villages. But according to an internal document maintained by the Forum against Corporatisation and Militarisation—a civil-society collective of individuals and organisations working on human-rights issues in Bastar—the local Adivasis identified one of the six, Aytu Punem, as a civilian. He was recently married, the document noted.

The social activist Bhatia has noted that the “pace of these fake encounters has increased sharply” since January. In a surprise result the previous month, the Bharatiya Janata Party had won the state elections to form the new Chhattisgarh government under Vishnu Deo Sai. During a virtual meeting in the last week of May, local activists noted that the party had chosen a tribal chief minister in an effort to escape liability for the reckless killing of Adivasis in their anti-Maoist operations. In the run up to the elections, the union home minister, Amit Shah, had repeatedly stated that a BJP government would end Naxalism in the state. Shah repeated the claims in the campaign for the general elections—and in the build-up to the polls, security forces doubled down on its aggressive operations.

On 2 April, security forces claimed to have killed 13 Naxalites in an encounter in Bijapur, which forms part of the Bastar Lok Sabha constituency and went to polls on 19 April. But once again, the claims were challenged by locals, who stated that there were civilians among the numbers counted by the security forces. Kamli Kunjam, a resident of the district’s Nendra village with a hearing disability, was among those identified as a Maoist killed during the encounter. But Behanbox reported that according to her family, Kunjam was forcibly taken from her home by police officials, her clothes torn, and dragged through the mud into the forest.

Similarly, the police identified Chaithu Pottam of the nearby Korcholi village among the slain Maoists. But according to his wife, Somi Pottam, Chaithu had gone into the forest after two-hours of firing to collect the Mahua flowers—a crucial source of income for the Adivasis—before the stray cattle eat them. Chaithu never returned, and two days later, Somi was asked to go a hospital to identify his dead body. Both families denied that Kunjam or Chaithu had any involvement with the Maoists.

Three days before the elections in Bastar, security forces conducted another operation in which 29 Naxalites were allegedly shot dead in an exchange of firing—one of the largest anti-insurgency operations in Chhattisgarh’s history. Yet, according to a statement released by the CPI (Maoists), only 12 died in an actual encounter; the remaining 17 were reportedly detained, tortured and later killed in cold blood. On 30 April, security forces killed 10 more individuals. Once again, ground reports indicated that among the dead were four villagers, civilians caught in the crossfire while participating in traditional rituals in the early hours of that day in Kanker district’s Kakur and Mangweda villages.

On 10 May, security forces reported another encounter, in which they killed 12 Maoists in the Bijapur’s Pidwa forest. However, families of the slain identified the men as unarmed tendu-leaf pickers, who were rounded up by the police and killed despite identifying themselves as civilians. On 23 May, security forces claimed to have killed seven more Maoists in two separate encounters on the border of Bijapur and Narayanpur districts. A press statement released by FACAM identifies Sono Juri, an Adivasi farmer, as one of the seven. According to the statement, Juri was running away from the firing when he was shot dead. In the latest reported encounter, two more Maoists were said to have been killed on 30 May.

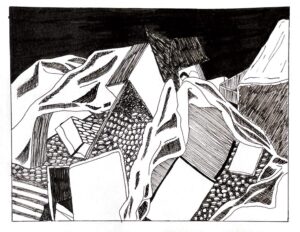

Even going by official numbers submitted to the Lok Sabha in March 2023, between 2018 and 2022, the operations in Chhattisgarh have killed more civilians than Naxalites or security forces. Over the five years, the number of civilian deaths stood at 335, while those of Naxalites and security forces was 327 and 168, respectively. The Article 14 investigation found that across a twenty-year period, till 2022, even home ministry numbers found that the anti-Maoist operations had claimed 2,039 civilian lives, which was 35% higher than those of security forces, and 40% higher than those of Maoists.

These numbers are alarming, and they do not even take into account the disputed claims about the Adivasi civilians who are identified as Maoists. In the first five months of 2024, the disappearance of bodies by the state already exceeds those of preceding years.

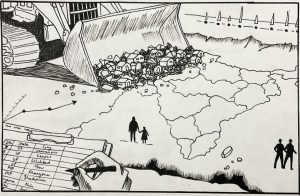

The events in Bastar form part of a pattern in which the state takes advantage of the securitised threat of Naxalism to create a false narrative of anti-insurgency operations while erasing Adivasis from public discourse. In the process, the state is able to justify its indiscriminate killing of Maoists and civilians alike, simplifying the complex social realities of tribal regions to a black-and-white law and order problem that requires an aggressive, militaristic solution. This process involves portraying the targeted group as inherently inferior, dangerous, or evil—a dehumanisation that makes it easier for the general public to accept, and even support, the extreme violence against civilians.

Related Posts

The relentless rise of civilian killings in Bastar under Chhattisgarh’s new BJP government

On the first day of 2024, a six-month-old girl, Mangli, was shot dead by Indian security forces in Bastar. The bullet went through Maase Sodi’s hand, who was holding her daughter at the time, cutting through her fingers before it killed the infant girl. The death was the first of dozens in the region this year, which has been marked by a surge in operations by security forces. While the state and central governments have made proud declarations about the number of Maoists killed in these encounters, Adivasi locals have repeatedly contested these claims, and accused the security forces of killing civilians.

In the case of Mangli’s death, too, government, police and paramilitary officials claimed that the six-month-old died during a crossfire with Maoists. But eyewitness accounts belie the official version. In a detailed investigation for Article 14, Malini Subramaniam reported that Sodi and other locals had assembled in the village of Mutvendi, in Bijapur district, to protest against a road-construction project. The administration was constructing a road that would connect the remote village to Gangaloor, a key junction in the district, 21 kilometres away. The construction would destroy important trees for the locals, including a mango and salfi tree essential for Sodi and others, and the villagers had gathered in a peaceful protest to save their trees. Eyewitnesses told Subramaniam that the police and paramilitary forces randomly started firing at them, killing Mangli in the process.

The six-month-old’s death was the prologue to a number of civilian killings in Chhattisgarh’s Bastar division, which comprises the seven districts of Bastar, Bijapur, Dantewada, Kanker, Kodagaon, Narayanpur and Sukma. As of 30 May, security forces have reportedly killed 118 Maoists in the region, but according to locals and activists, many of them were civilians.

On 20 January, two teenage girls, Nagi Punem and Soni Madkam, and 40-year-old Kosa Karam, a father of five, were among a group of eight Adivasis from Bijapur’s Nendra village, travelling to Gorna village to join a protest against the killing of Mangli. En route, the social activist Bela Bhatia said, security forces began firing at the group, killing the three of them immediately and detaining and beating the other five in the group, which included other teenagers as well as ten-year-old Chottu Podiam. Bhatia recounted these details after speaking to four members of the group who were subsequently released, including Jimme Uika, who bore witness to the hour-long gunfire that took the lives of the three villagers. The state police, however, claimed to have killed three Maoists.

On 27 January, Podiya Mandavi, a farmer and father of four from Pedka village, died in police custody. Mandavi had been detained by the police, accused of involvement in a Maoist Improvised Explosive Device (IED) attack from April last year, which had killed ten security personnel and a driver. While police officials claimed that Mandavi “suddenly died of a stroke,” his body reportedly bore knife scars that suggested custodial torture. Despite the efforts of the activist Soni Sori and Mandavi’s kin to seek justice, the police refused to register a first information report concerning his death.

On 30 January, in Bhairamgarh tehsil near the Indravati river, 22-year-old farmer Ramesh Oyam was killed. According to his brother-in-law, Payko Kunjam, Oyam was shot by security forces while he was bathing in the river. According to the Article 14 report, the local superintendent of police acknowledged the civilian casualty but refuted any police involvement. Oyam was not affiliated with any political party nor the People’s Liberation Guerrilla Army (PLGA)—the armed wing of the Communist Party of India (Maoists)—and was killed the day after the birth of his child.

On 2 February, Piso Kovasi and Kanharu Duru, residents of Gomagal village in Narayanpur, were ambushed and killed by security forces. According to Piso’s uncle, Kume Kovasi, his nephew had gone to the nearby forest with three others to drink sulphi, a traditional drink extracted from trees, when they came under fire. The police have reportedly refused to register complaints by Kume and other villagers, and accused the two of being Maoists from whom they’ve recovered two weapons—claims that the locals refute.

On 27 March, the police reported that six Maoists had been killed in a gunfight in the forest near Bijapur’s Chikurbhatti and Pusbaka villages. But according to an internal document maintained by the Forum against Corporatisation and Militarisation—a civil-society collective of individuals and organisations working on human-rights issues in Bastar—the local Adivasis identified one of the six, Aytu Punem, as a civilian. He was recently married, the document noted.

The social activist Bhatia has noted that the “pace of these fake encounters has increased sharply” since January. In a surprise result the previous month, the Bharatiya Janata Party had won the state elections to form the new Chhattisgarh government under Vishnu Deo Sai. During a virtual meeting in the last week of May, local activists noted that the party had chosen a tribal chief minister in an effort to escape liability for the reckless killing of Adivasis in their anti-Maoist operations. In the run up to the elections, the union home minister, Amit Shah, had repeatedly stated that a BJP government would end Naxalism in the state. Shah repeated the claims in the campaign for the general elections—and in the build-up to the polls, security forces doubled down on its aggressive operations.

On 2 April, security forces claimed to have killed 13 Naxalites in an encounter in Bijapur, which forms part of the Bastar Lok Sabha constituency and went to polls on 19 April. But once again, the claims were challenged by locals, who stated that there were civilians among the numbers counted by the security forces. Kamli Kunjam, a resident of the district’s Nendra village with a hearing disability, was among those identified as a Maoist killed during the encounter. But Behanbox reported that according to her family, Kunjam was forcibly taken from her home by police officials, her clothes torn, and dragged through the mud into the forest.

Similarly, the police identified Chaithu Pottam of the nearby Korcholi village among the slain Maoists. But according to his wife, Somi Pottam, Chaithu had gone into the forest after two-hours of firing to collect the Mahua flowers—a crucial source of income for the Adivasis—before the stray cattle eat them. Chaithu never returned, and two days later, Somi was asked to go a hospital to identify his dead body. Both families denied that Kunjam or Chaithu had any involvement with the Maoists.

Three days before the elections in Bastar, security forces conducted another operation in which 29 Naxalites were allegedly shot dead in an exchange of firing—one of the largest anti-insurgency operations in Chhattisgarh’s history. Yet, according to a statement released by the CPI (Maoists), only 12 died in an actual encounter; the remaining 17 were reportedly detained, tortured and later killed in cold blood. On 30 April, security forces killed 10 more individuals. Once again, ground reports indicated that among the dead were four villagers, civilians caught in the crossfire while participating in traditional rituals in the early hours of that day in Kanker district’s Kakur and Mangweda villages.

On 10 May, security forces reported another encounter, in which they killed 12 Maoists in the Bijapur’s Pidwa forest. However, families of the slain identified the men as unarmed tendu-leaf pickers, who were rounded up by the police and killed despite identifying themselves as civilians. On 23 May, security forces claimed to have killed seven more Maoists in two separate encounters on the border of Bijapur and Narayanpur districts. A press statement released by FACAM identifies Sono Juri, an Adivasi farmer, as one of the seven. According to the statement, Juri was running away from the firing when he was shot dead. In the latest reported encounter, two more Maoists were said to have been killed on 30 May.

Even going by official numbers submitted to the Lok Sabha in March 2023, between 2018 and 2022, the operations in Chhattisgarh have killed more civilians than Naxalites or security forces. Over the five years, the number of civilian deaths stood at 335, while those of Naxalites and security forces was 327 and 168, respectively. The Article 14 investigation found that across a twenty-year period, till 2022, even home ministry numbers found that the anti-Maoist operations had claimed 2,039 civilian lives, which was 35% higher than those of security forces, and 40% higher than those of Maoists.

These numbers are alarming, and they do not even take into account the disputed claims about the Adivasi civilians who are identified as Maoists. In the first five months of 2024, the disappearance of bodies by the state already exceeds those of preceding years.

The events in Bastar form part of a pattern in which the state takes advantage of the securitised threat of Naxalism to create a false narrative of anti-insurgency operations while erasing Adivasis from public discourse. In the process, the state is able to justify its indiscriminate killing of Maoists and civilians alike, simplifying the complex social realities of tribal regions to a black-and-white law and order problem that requires an aggressive, militaristic solution. This process involves portraying the targeted group as inherently inferior, dangerous, or evil—a dehumanisation that makes it easier for the general public to accept, and even support, the extreme violence against civilians.

SUPPORT US

We like bringing the stories that don’t get told to you. For that, we need your support. However small, we would appreciate it.

Related Posts

இந்தியத் தலைநகருக்கு அருகில் ஒரு கிராமத்தில், ஓர்?