The obligation to deny: Accountability (or the lack thereof) in cases of custodial deaths in India – 3

In India, the value and significance of accountability stem not from what it describes and espouses, but from the lack of it. The criminal justice system skirts around the issue of accountability, its institutions often complicit in the perpetuation of violence.

In part three of this series, we analyze the types of accountabilities that take place within the various institutions that deal with custodial violence and torture in India. These institutions include the Police, the judiciary, the executive, the medical fraternity and the national and state human rights commissions. We examine the status of 15 cases of custodial deaths between 2015 and 2016, whether any compensation was provided to the victims’ families and the status of inquiries by different governmental bodies, while also highlighting independent inquiries by human rights organizations and civil society groups that have taken place in these cases. While there are gaps in our data, it is evident that accountability is rarely a concern for institutions of the State, which are bound to protect and uphold the rights of victims.

In India, the Police hardly face any legal consequences for their brutality and violence against citizens. Accountability remains a challenge because Section 197 of the Code of Criminal Procedure (CrPC) provides immunity from prosecution to all public officials unless the Government approves it. This is a provision that the central and state governments often use to avoid prosecuting officials thus making conviction in cases of custodial torture and deaths difficult.

On 3 October 2016, Minhaj Ansari and two of his friends were arrested from their village Dighari in Jamtara district, in Jharkhand. Sonu Singh, a Vishwa Hindu Parishad (VHP) leader, made the first complaint to the Police against Ansari for allegedly posting a photograph of himself with a calf on a WhatsApp group, followed by another of him posing with beef. The participants of the group found the images “obscene” and complained to the Police. After two days in police custody, Ansari was taken to a hospital in Ranchi to be treated for injuries and was eventually declared dead on 9 October 2016. A First Information Report (FIR) was registered against police officer Harish Pathak for attempt to murder, which was later changed to murder after Ansari’s death. Harish Pathak was suspended, but eventually the order was revoked after he was denied one increment. The trial against him did not begin and Pathak was able to get a stay on his case.

Sonu Singh, the VHP leader, was not present in the chargesheet filed by the Police. In 2017, Senior Advocate Abdullah Allam filed two writ petitions at the Jharkhand High Court – one for compensation and a job for Ansari’s family members and the other for an investigation by the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI) and punishment against Harish Pathak. As per news reports from 2018, the Criminal Investigation Department (CID), which is a branch of the state Police, found that Ansari was beaten after being taken to the police station and was going to file a chargesheet naming Harish Pathak under Section 304 (punishment for culpable homicide not amounting to murder) of the Indian Penal Code (IPC). In June 2020, Harish Pathak was posted in Jharkhand Chief Minister Hemant Soren’s constituency. A June 2020 news report claimed that Pathak’s suspension order was eventually revoked. The trial for the case is yet to begin at the time of writing. Speaking to news agency eNewsroom in June 2020, advocate Allam mentioned that “Pathak had registered two cases against Ansari, one for circulating the beef message and the other against the victim’s family for attacking him. So, we initially demanded that the CBI club all three FIRs and investigate the matter.” TwoCircles.net on 22 July 2020 reported that the family had received four hundred thousand rupees as compensation.

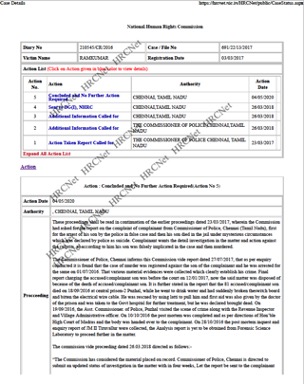

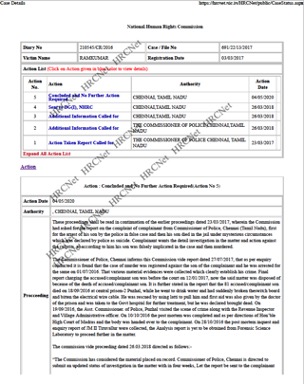

Ramkumar, from Tamil Nadu, was arrested by the Chennai Police on 2 July 2016 in connection with the alleged murder of Swathi, a 24-year-old IT professional on 24 June 2016. He died on 18 September 2016 in judicial custody in a Puzhal Central Prison – a high-security prison in Chennai. On 4 May 2020, the National Human Rights Council (NHRC) closed the file regarding Ramkumar’s custodial death stating that the complaint was not substantiated: based on the Police report, Ramkumar had been arrested on properly formed charges and there was no reason to believe that his death was not a suicide. The NHRC registered a case in March 2017 and closed it in 2020, deciding that there was “nothing on record” to indicate Ramkumar was falsely implicated or murdered.

In December 2021, the Madras High Court stayed all further proceedings on the suo motu case initiated in 2020 by the Tamil Nadu State Human Rights Commission (TNSHRC) regarding the death. The High Court stayed the proceedings based on a petition filed by R. Anbalagan, the then Superintendent of Puzhal Central Prison-II. The petitioner, who served as the superintendent of the central prison when the incident occurred on 18 September 2016, stated that the TNSHRC could not initiate the proceedings after a delay of four years as it would not have the power to condone the delay. The petitioner also noted that the report of the postmortem examination conducted by five doctors, including one from the All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS) in New Delhi, concluded that the victim appeared to have died due to electrocution. The Judicial Magistrate-II of Tiruvallur reached a similar conclusion after an investigation was conducted under Section 176 of the CrPC (investigation into deaths in police custody are to be conducted by a judicial magistrate), and the NHRC too found that the allegations leveled by Ramkumar’s parents were not substantiated by any record. On 19 September 2016, the Madras High Court also dismissed the petition filed by P. Ramkumar’s father seeking a probe by the CBI.

However, on 31 October 2022, more than six years after Ramkumar’s death, the TNSHRC recommended the Tamil Nadu government to pay a compensation of a million rupees to Ramkumar’s father within a month. The TNSHRC noted that “the Government of Tamil Nadu is also responsible for the death of Ramkumar in Puzhal Prison and hence the state is liable to pay compensation to the father of the deceased namely Paramasivan for the suspicious death of his son in the Puzhal Prison.” This recommendation was issued after considering the oral and documentary evidence produced by the TNSHRC’s Investigation Wing and witnesses. The TNSHRC said: “Suspicion arises[…] whether the prisoner Ramkumar committed suicide by electrocution due to self-inflicted joule injuries or some other person electrocuted the body of the deceased or the reason stated in the final report by the AIIMS doctor Dr. Sudhir Gupta that the deceased died due to asphyxia.”

The TNSHRC also said that it was for the prison authorities to protect and promote the human rights of the prisoner and further said it was not satisfied with the report submitted by its own Investigation Wing, as well as with the report submitted by the Judicial Magistrate and also the final report of the investigating officer in the criminal case. “The authorities, who had examined the witnesses and submitted their report, had not given any valid reason that Ramkumar committed suicide,” the Commission said. Hence, the TNSHRC was of the opinion that an independent probe is “very much essential” to find out how P. Ramkumar had actually died and recommended the State government to constitute an independent probe to find out whether Ramkumar died by suicide by pulling and biting into a live electric wire inside Puzhal prison as claimed by the respondents, or due to homicidal injury as alleged by the complainant.

Shameel Basha was picked up by the Police in connection with the missing person’s case of a former female colleague, kept in illegal detention and tortured from 15 to 18 June 2015. He died in Rajiv Gandhi Government General Hospital, Chennai, Tamil Nadu, on 26 June 2015, following health complications that he reportedly developed while he was in police custody. In Basha’s case, the Vellore Superintendent of Police V. K. Senthil Kumari said that a magisterial inquiry on the incident was opened after a case was registered under Section 176 of the CrPC. Based on the inquiry, Martin Premraj, the inspector in charge of placing Basha in custody, was transferred from Pallikonda station to the prohibition enforcement wing. This was done after Basha was admitted to hospital on 18 June. When Basha died on 26 June, Premraj was on medical leave. Two days later, Premraj and six other policemen from the Pallikonda station were placed under suspension. Premraj was absconding when asked to appear before the Crime Branch-Central Intelligence Department office in July 2015. In November 2016, Premraj’s writ petition was submitted before the Madras High Court asking for his suspension to be revoked as he had been suspended for more than three months and had not received any chargesheet. In response to this, the High Court directed that Premraj be placed in some other non-sensitive post. The Government paid Rs. 500,000 to the kin of the victim and provided proof of payment to the NHRC, which closed the complaint as a result.

Meenkulambu Karthik was picked up by the Police for a robbery in Chennai, Tamil Nadu, on 19 September 2016. He died on 21 September 2016, when he was rushed to the hospital as he complained of breathlessness. The hospital authorities said that he was brought dead. A fact-finding probe launched by the Communist Party of India – Marxist (CPIM) into his custodial death indicted the Chennai police of Karthik’s murder. The fact-finding team urged the Uthiramerur magistrate to record the statements of the co-suspects who were witness to Karthik’s torture in illegal custody besides registering a murder case against the police officials. The probe established that the victim was under custody from 19 September until his death on 21 September 2016. The Police paid Rs. 200,000 to the family which, according to the fact-finding probe, substantiated the fact that Karthik was killed in police custody. The Chennai Police had not acted on the petition filed by Karthik’s mother, and the CPIM probe highlighted the manufactured claims of the Police that Karthik and his friend A. Arunachalam had figured in the CCTV footage in which a woman software professional was robbed in Thuraipakkam. The probe alleged that the officials had resorted to custodial torture only after they had learned that Karthik belonged to a Scheduled Caste group. Hence, the Police’s attribution of suspicion was not accepted. The doctors who were part of Karthik’s autopsy admitted in the death report that the body had aberrations on both thighs, “a scar on the right clavicle area [and] multiple bruises.” The CPIM team noted that, “The namesake suspension of the lower rung cadre would not be enough. The personnel from Kannagi Nagar, Semmenjeri, Thuraipakkam and Neelankarai Police stations should be subjected to identification parade before Arunachalam and four other youth, also from Chinthadripet, who were detained illegally along with the deceased. The men were also subjected to custodial torture.” The fact-finding team also demanded that the jurisdictional Deputy Commissioner of Police (DCP) and the Assistant Commissioner of Police (ACP) be placed under suspension for the custodial violence besides transferring the investigation to the CBI and initiating prosecution for bribing the family with Rs. 200,000. Karthik’s family returned the amount three days after his death. This was the first installment of the Rs. 400,000 promised by a police officer. According to reports, they were “forced to keep the custodial violence under wraps”.

Kuppuswamy was a small shop owner who was arrested on 15 August 2016, for illegal liquor sale. He was subsequently lodged in Madurai Prison (Tamil Nadu) under judicial custody and died on the same day. Kuppuswamy’s family members refused to believe the police version of events which claimed that Kuppuswamy had died due to illness, and staged a dharna (protest) in front of the Sanarpatti police station. They also accused the cops of arresting him in a false case. The NHRC complaint filed by the Superintendent of Prisons, Central Prison, Madurai, one day after Kuppuswamy’s death was closed as the TNSHRC intimated the NHRC in October 2016 that they have taken cognizance of the matter. At the time of writing, no further updates are known regarding this case.

Mohan, a Sri Lankan national in his early forties, was picked up by the Police in Tamil Nadu in an alleged fake passport racket case. According to reports, Mohan was taken into custody and interrogated for three days. While he was being questioned on the night of 4 September 2015, he collapsed and was admitted to a nearby private hospital where he was declared dead. A case under Section 176 CrPC was registered and referred for judicial inquiry. A friend of Mohan’s said that the Police managed to get in writing from Mohan’s partner that he had died of cardiac arrest. They also promised monetary compensation and a job for her eldest son. At the time of writing, no further updates are known regarding this case.

Gokulakannan was a contract laborer who was picked up around midnight by the Police in connection with a murder, and later rushed to hospital in Salem, Tamil Nadu, where he was declared “brought dead.” He died on 6 June 2015. According to reports, local activists said that the Police threatened and bribed the family to take back allegations of custodial torture. Tamil Nadu People’s Rights Movement alleged that senior police officials had forced the family members to accept Rs. 1,200,000 to silence them. “Gokulakannan’s family members were threatened by the Police and forced to accept the money. His family admitted it to us when our team spoke to them.” Gokulakannan’s mother confirmed the same to a news portal. “They warned us of dire consequences if we pursued the case. We didn’t have any option but to accept the money.” Three police officers, including a sub inspector, were also suspended, for negligence of duty and for picking up a man for interrogation while he was unwell.

Bujji was detained for his role in the killing of a police constable in Tamil Nadu. He died a few hours after he was taken into police custody, on 15 June 2016. The Police denied that Bujji’s death was a custodial murder and said that he had died as a result of heart attack. The National Confederation of Human Rights Organizations (NCHRO) and other activist organizations sought the suspension of the police personnel involved in Bujji’s death. The Tamil Nadu Chief Minister Jayalalitha had initially announced an aid of Rs. 500,000 for the family of the constable Bujji was accused of stabbing, but later revised the amount to Rs. 10,000,000.

On 21 March 2015, Sheikh Hyder was arrested for an alleged bicycle theft and died the same day in a police station in the state of Telangana. The State Minorities Commission in Telangana ordered a probe by a four-member committee. The probe found that it was a case of custodial death and recommended that action should be taken against responsible police officers and doctors. The local district collector ordered an Executive Magistrate inquiry into Hyder’s death in clear violation of Section 176 of the CrPC. The Executive Magistrate’s report used the Police description of Hyder’s injury verbatim. In March 2015, following public attention in the matter, the inspector and a head constable of the police station where Hyder was arrested were suspended. The Andhra Pradesh SHRC (the SHRC for Telangana state had not yet been set up in 2015) took cognizance of the matter on 1 April 2015. The Police submitted its report on the case to the Andhra Pradesh SHRC in April 2015. Even though activists criticized it for being misleading and poorly written, the report did admit that Hyder’s death was caused by police negligence. A 2016 Human Rights Watch report, which conducted an in-depth investigation into Hyder’s case, mentioned that his family alleged abuse, but the Police did not file an FIR against the police officials implicated in arresting and torturing Hyder. It was also found that both the SHRC and the minority commission had investigated the death and recommended that the state government pay compensation to the family. However, the family had not received any compensation at the time of writing.

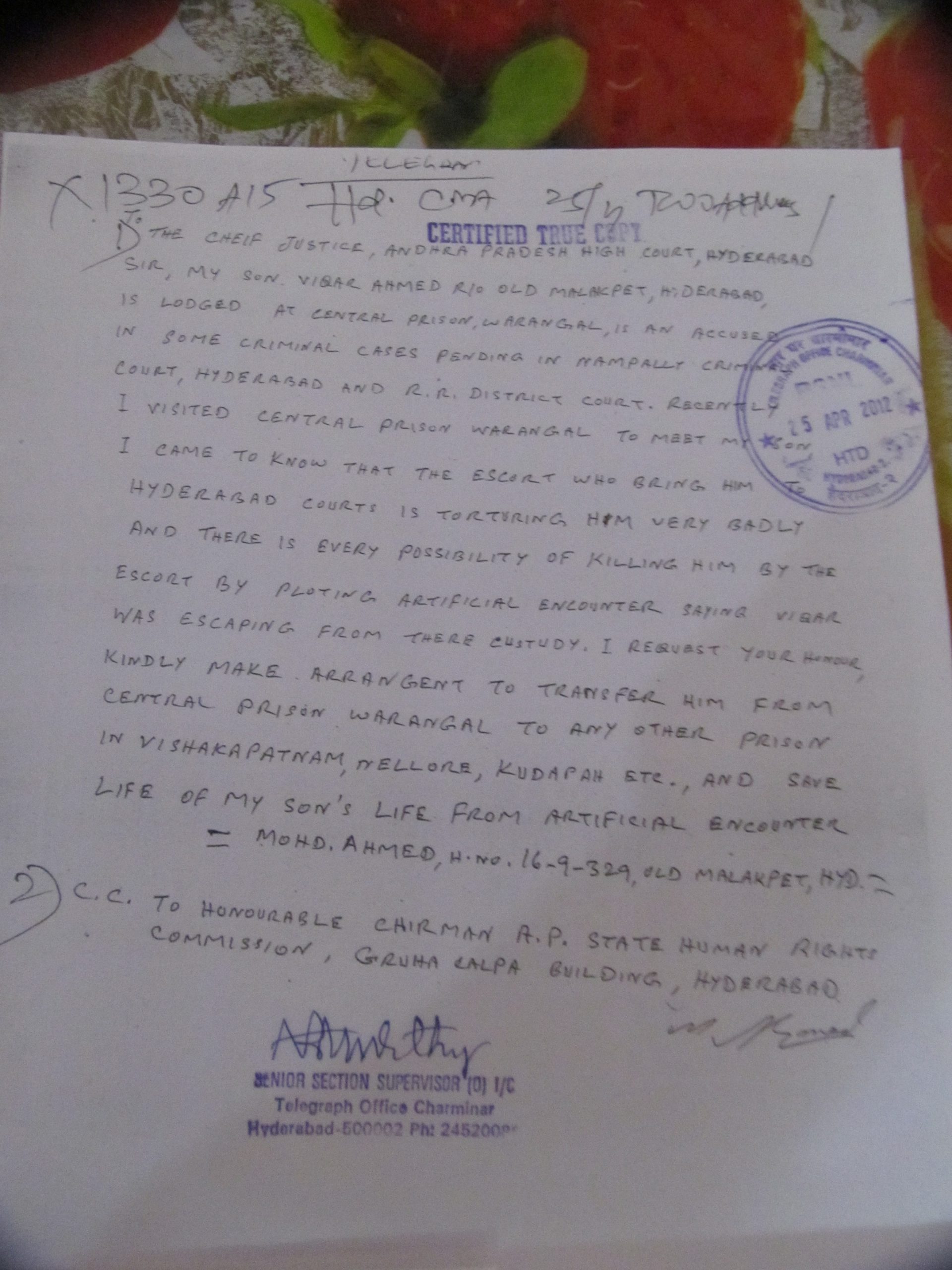

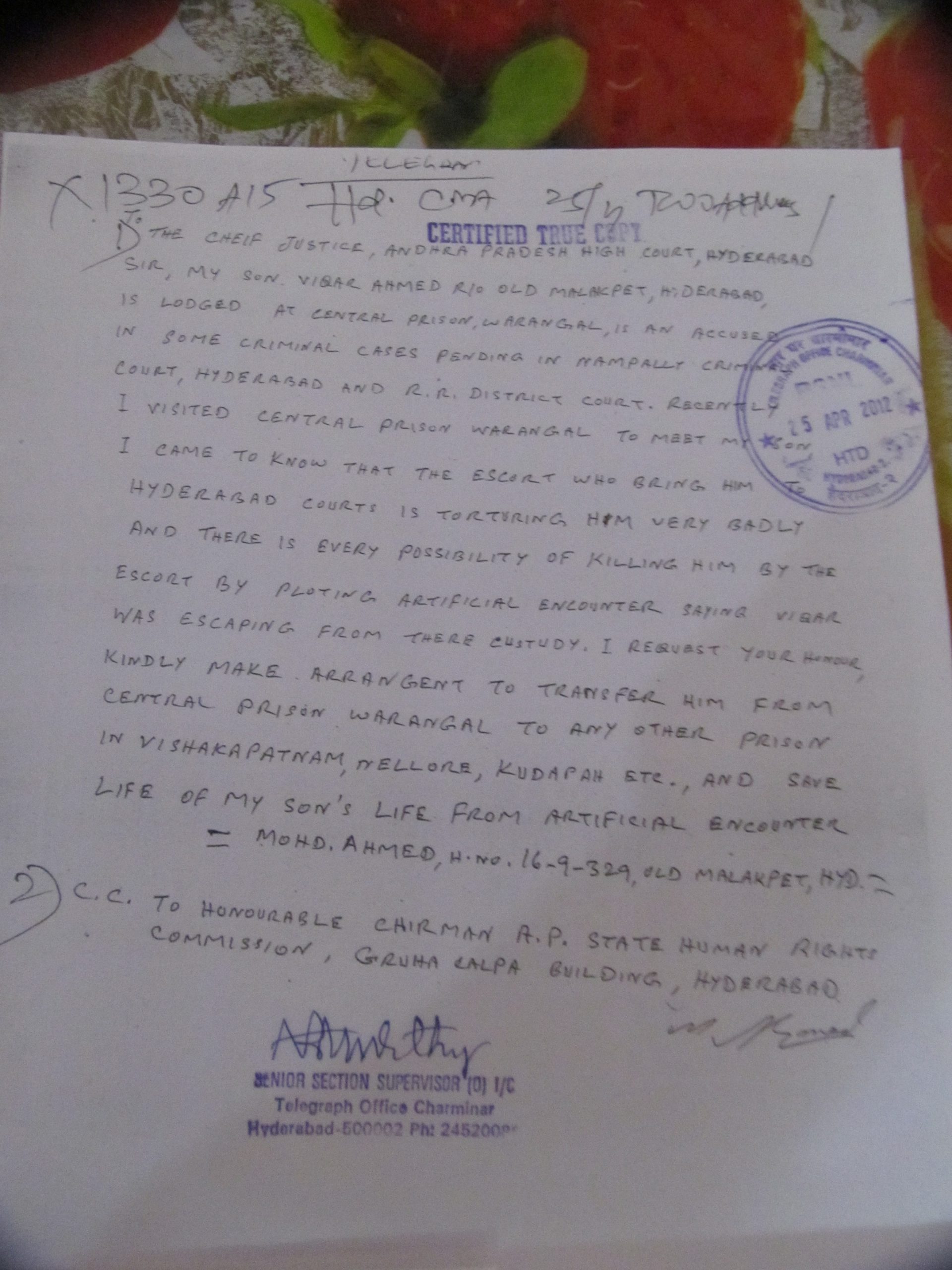

Viqaruddin Ahmed was a suspect in the Mecca Masjid bombing in which two policemen died in Hyderabad. The Police killed Ahmed and four others in an “encounter” near Alair in Telangana on 7 April 2015 while 17 policemen escorted him to the Hyderabad Court from Warangal Jail. Ahmed had previously expressed concern that he would be abused on the way to or from prison by the Police. In April 2012, his father had also filed a complaint mentioning that he feared for his son’s life. Ahmed was first arrested in 2010 and was accused of forming a militant group that targeted police officers. Gulam Rabbani, the lawyer representing Ahmed’s father, stated that no criminal report was recorded when he tried to register a complaint regarding Ahmed’s alleged murder. Rabbani then filed a court case demanding that charges of murder should be filed against the Police. Although the case was admitted in Court, and Rabbani said that according to procedure, a hearing should have taken place in the first week of June 2015, the hearing did not take place. Speaking to AlJazeera in 2015, Ahmed’s father claimed that the Police was waiting for an opportunity to murder his son.

While there are discrepancies in how police custody is defined in the law, according to a 1980 Supreme Court judgment, police custody includes being taken to jail in the custody of the Police. Going by this definition, Ahmed’s case would be a clear case of death while in police custody. However, the details regarding the location of the death have not been included in the NCRB Crime in India reports after 2014. Therefore, from the NCRB data it cannot be ascertained where the victim died which is a useful detail to have especially when fighting legal cases.

The fact finding report conducted from 12 to 14 April 2015 by Civil Liberties Monitoring Commission (CLMC), a Hyderabad-based human rights organization stated that in Ahmed’s case the Alair Police had filed a case against the deceased under Section 307 of the IPC (attempt to murder), but did not file a case against the Police personnel involved in the killing under Section 302 of the IPC (punishment for murder).

A Special Investigation Team (SIT) comprising six police officials was formed on 13 April 2017 to inquire into the matter and the NHRC took cognizance of the matter as well. In April 2018, the SIT was yet to submit its report, according to TwoCircles.net. The NHRC found violation of rights and torture and requested a compensation of Rs. 500,000 to the surviving family members of the accused. The last hearing in this case was on 16 July 2020 and the matter was disposed of as completed. “Although the NHRC directed the Government to pay compensation to the victims’ families, unfortunately the Government has not complied with the orders of the NHRC and till date no compensation money has been released to the victims’ families,” CLMC director Lateef Khan told us via email. No judicial magistrate inquiry was ordered or conducted in this matter even though it is a statutory requirement under Section 176 of the CrPC.

On 29 April 2015, the Executive Magistrate of Nalgonda District, under whose territorial jurisdiction the encounter had taken place, was appointed by the Telangana government to preside over the magisterial inquiry despite the fact that a government order was issued in clear violation of Section 176 of CrPC (that only authorizes the judicial magistrate to inquire into custodial deaths). CLMC filed a writ petition in the High Court (Writ Petition number 12453/2015) demanding a judicial magistrate inquiry, but it did not uphold this statutory requirement and the matter still stands as sub judice. “Two writ petitions have been pending in the high court for the past seven years but the matter has been put in cold storage and since 2015 no hearing was conducted in this matter in the high court,” added Khan. An executive magistrate inquiry headed by a government cadre revenue officer was conducted three months after the encounter: it gave a clean chit to the police officer involved and did not find any police fault or excessive use of force.

In G. Bonappa’s case the Police claim that he was inebriated during the Bonalu festival, was dancing with a procession in Hyderabad and was picked up on 2 August 2015 after he got into a fight with a home guard. He died the following day on 3 August 2015. Bonappa’s family, however, alleged that the Police had brutally beaten him up. “When we took him home, he was not able to eat or drink. He was exhausted and appeared uneasy. We took him to the police station and asked them what had happened. They responded very rudely and abused us. Later, they sent constables with us to take him to hospital. He died on the way,” Bonappa’s cousin told Deccan Chronicle on 4 August 2015. G. Arjuna, the victim’s brother, claimed that Bonappa was in good health before he was arrested. However, after the Police released him, Bonappa was exhausted and half-conscious and his throat, legs and hands were swollen. “He could not speak. The Police had beaten him up for many hours causing internal injuries,” Arjuna said. Hyderabad Police commissioner Mahender Reddy ordered a probe on 5 August 2015 into the death of Bonappa. A team from the Central Crime Station in Hyderabad had taken up the investigation after booking a case under Section 174 of the CrPC (death by suicide or suspicious death). According to an 8 August 2015 news report in Deccan Chronicle, two sub inspectors involved in the case were removed from the police station and attached to the headquarters pending an inquiry into Bonappa’s death.

Padma was called in for questioning on 21 August 2015 to the Asifnagar police station in Hyderabad, Telangana, in connection with a theft case. She was called for questioning when she was sick, and called in again the next day on 22 August, when she collapsed and died, according to the Police. In Padma’s case, seven police officers – the Asifnagar police station inspector, a sub inspector, an assistant sub inspector, one head constable and three constables – were suspended in the interests of a fair inquiry and for gross negligence in keeping her during odd hours resulting in severe health complications, which ultimately resulted in her death in the hospital. The SHRC took cognizance of the case and requested detailed reports from the Hyderabad Commissioner and the hospital where Padma died. A preliminary inquiry conducted into Padma’s death revealed that the Asifnagar police personnel did not inform their superior officers about detaining three women as part of the probe into the theft case, nor did they take into account Padma’s medical condition before questioning her. “As a procedure, the policemen should inform their superiors when they detain or take women into custody in any case. But, in this case they did not do so. As a result, the woman collapsed during questioning by the Police and died some hours later at a hospital,” an official, who conducted the investigation, said.

Lakshman was accused in a murder case and was arrested by the Pulkal Police in Medak district,Telangana. On 12 March 2015, Lakshman died while the Police were taking him to the hospital. In Lakshman’s case four policemen – inspector V. Nagaiah, sub-inspector Lokesh and two escort constables, Yadaiah and Uday – were suspended for negligence of duty. A magisterial inquiry was ordered as well. The superintendent of Police at Medak mentioned that they registered a case under Section 176 of the CrPC (inquiry into the death of any person while in police custody) in connection with the incident. Lakshman’s family and local villagers alleged that this was a case of police brutality and they suspected foul play. At the time of writing, the report from the magisterial inquiry was not accessible and the NHRC does not have records of this case.

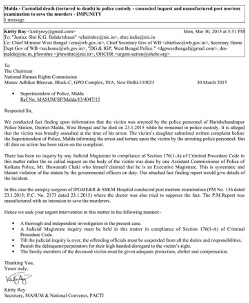

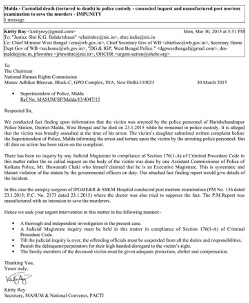

Obaidur Rahman was arrested by the West Bengal police in a criminal case arising out of a land dispute with his neighbor. Rahman died in police custody in Malda, West Bengal, within 24 hours of his arrest, on 21 January 2015. No judicial magisterial inquiry – which is mandatory in all cases of custodial deaths – was held in Rahman’s case. An executive magistrate initiated an inquiry and filed the report in January 2015. However, this was a blatant miscarriage of the rules stipulated in cases of custodial deaths. MASUM’s secretary and national convenor, Kirity Roy, filed a complaint with the NHRC requesting that a judicial magistrate inquiry would be carried out.

Letter of Complaint to the NHRC requesting that a judicial magistrate inquiry be carried out in Obaidur Rahman’s case. Source: Mr. Kirity Roy, MASUM, West Bengal.

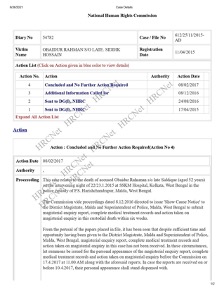

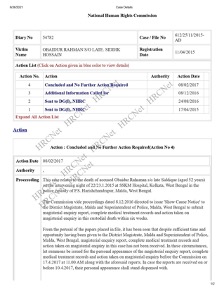

As per the 2016 Human Rights Watch report, Rahman’s family alleges that when his condition continued to deteriorate in the Malda hospital, the doctors there suggested that he be taken to a hospital in Kolkata but the Police refused. So the family wrote to the Superintendent of Police requesting a transfer for further care. Following the letter, police personnel took Rahman to the Bangur Institute of Neurosciences, Kolkata, where he was declared dead on arrival. The post-mortem determined that no internal or external injuries could be detected and that Rahman died because of brain stem hemorrhage due to a cerebrovascular accident – the medical term for a stroke. The post-mortem report was signed by the same sub inspector against whom the family had filed a complaint. The family also told Human Rights Watch that they faced harassment and intimidation after his death. The NHRC took cognizance of the matter (image below): “The Investigation Division after analyzing the various reports has suggested closing of the case as there is no foul play or negligence on part of the police officials and the death was natural and due to illness. The Commission also independently considered the various reports and suggestions made by the Investigation Division and found no reason to differ with the suggestions of the Investigation Division”, thereby closing the case on 5 December 2017.

Action taken by the NHRC in Obaidur Rahman’s case. Source: Mr. Kirity Roy, MASUM, West Bengal

Bhushan Deshmukh was arrested under the Arms Act for possession of illegal weapons on 20 September 2015 in Kolkata, West Bengal. Burtolla Police claimed he died of diarrhea, but a post-mortem report revealed multiple injuries all over the body, suggesting that he was beaten up by more than one individual. It was later found that Deshmukh was actually arrested on 19 September 2015, a day before police records show, and was taken to a private hospital by the Police in violation of protocol on 24 September 2015. Deshmukh died in hospital the following day on 25 September 2015 night. The officer-in-charge of Burtolla police station, the night duty officer, lock-up in charge and a constable present the night when Bhushan was beaten up by the Police, were suspended on 4 October 2015. A departmental probe was ordered against the four officers by registering a case of culpable homicide. The Metropolitan Magistrate, Kolkata, found that Bhushan died due to inflicted injuries and torture in police custody. The West Bengal SHRC took cognizance of the matter on 5 October 2015 and found that Deshmukh was left untreated for more than five hours in the lock-up after he started vomiting. The SHRC requested a compensation of Rs. 200,000 for the deceased’s family and ordered a departmental inquiry against police personnel involved in the case: sub inspector Pradip Kumar Rakshit, Bikash Biswas and Constables Hrikesh Mondal and Partha Sarathi Mondal. Sub inspector Bikesh Biswas, the investigating officer in the matter, was held primarily responsible by the inquiry. Importantly, the SHRC recommended that a Standard Operating Procedure be put in place regarding the duties of the Police when taking suspects into custody. The NHRC confirmed that the deceased had died due to torture in police custody and directed that Rs 500,000 compensation should be paid to the kin of the deceased. As of August 2018, proof of payment was submitted to the NHRC and the matter was closed.

While compensation to the families is important, it is also worth questioning whether the lives of victims of police torture, who are mostly young men and breadwinners, are worth just 200,000 or 400,000 rupees. While the moral implications of putting a value on a person’s life are always questionable, there are also inconsistencies on how the amount of the compensation is decided.

One challenge for accountability in custodial deaths is the propensity of government doctors to back police claims. Autopsy and forensic reports frequently support the Police version of events even where there is no apparent basis. Often, medical professionals conducting the autopsy and writing postmortem reports are under significant pressure from police officials to produce outcomes favorable to them. For example, in Obaidur Rahman’s case, the sub inspector against whom a complaint of torture was filed was also the one who signed the postmortem report.

Third degree methods are used as a euphemism for police torture in India. Writing in 1995, Amar Jesani outlined the relationship between medical ethics and police violence. Jesani’s paper lists reasons for doctors to remain silent when they encounter cases where the victim has been tortured by the Police. One reason is that most doctors are unaware of the correct medical procedures and codes of conduct, or doctors try to maintain the status quo due to their personal beliefs and biases. Socio-economic backgrounds play an influential role when it comes to viewing victims as criminals and as deserving of torture at the hands of the Police. In such cases, doctors remain silent and avoid reporting on instances of custodial violence and torture. The lack of training and care by medical professionals working in institutions closely associated with the Police and prisons leads to an increase in custodial deaths as well, as highlighted in a report by journalist Sukanya Shantha on prison conditions.

Every case of custodial death is supposed to be reported to the NHRC. The Police are required to send the findings of the magistrate’s inquiry to the NHRC along with the post-mortem report. The NHRC also calls for the autopsy to be filmed and is empowered to summon witnesses, order production of evidence and recommend that the government initiate prosecution of officials. However, in practice, its recommendations have mostly been limited to calling on the Government to provide compensation money to victims’ families or other immediate interim relief. Providing adequate and timely compensation to the victims’ families is important since most victims of custodial deaths are poor, young men, who were often the sole breadwinners in their families. Further, the compensation money ensures that the families have a chance at fighting long legal cases to ensure those who are responsible are brought to justice. However, as discussed, we found cases where the victims’ families have not received the ordered compensation money.

The SHRC is a recommendation body that was set up to investigate, promote and protect human rights at the state level in India. Anthropologist Ather Zia, in Resisting Disappearance: Military Occupation and Women’s Activism in Kashmir (2019), notes that while “the Government presents the SHRC as a major watchdog institution for safeguarding human rights, it remains a recommendation body and cannot penalize anyone. As it has no power of adjudication, the SHRC is seen as a “toothless tiger”.” (page 38)

The national and state human rights commissions have largely failed in their oversight role in cases of custodial killings. While the NHRC has a responsibility to seek both justice and relief for victims’ families by recommending prosecution of those who committed the crime and compensation for the victims, seeking prosecution often jeopardized the possibility of relief. “The two sadly should have gone together but they tended to clash,” Satyabrata Pal told HRW for their 2016 report on custodial deaths. “Most states would simply not accept the recommendation and therefore, since NHRC can only recommend and not compel, we would then fail in our duty to get both justice and relief.” There are also instances in which the NHRC closed cases without even recommending compensation, leaving the matter to the state government. Between April 2012 and June 2015, of the 432 cases of deaths in police custody reported to the NHRC, the commission recommended monetary relief of about Rs. 22.91 million (USD 343,400), but recommended disciplinary action in only three cases and prosecution in none. Similarly, the People’s Union for Democratic Rights (PUDR), a civil society organization working on human rights in India, notes that the role of the NHRC has been relegated to that of making recommendations in cases of custodial deaths. “The number of cases pending with the NHRC brings out the limitations of the commission as a mere elephant in the room,” highlighting the role of the NHRC as opposed to its intention of being an effective legal remedy when it was envisioned in 1993.

From the NCRB data on custodial deaths, it was found that 452 deaths were reported in custody between 2014 to 2018, but only 192 cases were registered, 118 policemen were charge-sheeted and no police personnel were convicted during this period. In some cases, investigation into custodial deaths is conducted by the same crime branch under which the police station falls and so the investigators will try their best to help their colleagues rather than conduct a fair and impartial investigation. As noted in part one of this series, there is a lack of political will to implement legal frameworks and measures proposed by international and Indian legal scholars. This lack of political will often leads to limited accountability for police personnel as perpetrators of torture and brutality against citizens. In a rare and important ruling in January 2016, the sessions court in Mumbai convicted four police constables of culpable homicide for the brutality that lead to 20-year-old suspect Aniket Khicchi’s death in custody in 2013. The constables were faced with seven years in prison; however, three of the four police constables were granted bail in June 2018 pending their appeal against the conviction which was to be decided by the High Court. As the 2016 Human Rights Watch report notes, “police abuse reflects a failure by India’s central government and state governments to implement accountability mechanisms. Despite strict guidelines, the authorities routinely fail to conduct rigorous investigations and prosecute police officials implicated in torture and ill-treatment of arrested persons.”

As is evident from the case details, there have been no convictions or arrests of police personnel involved. In some cases, formal complaints were not even registered against police personnel for torture, whereas the evidence points to the contrary. Even when police personnel were suspended, as in N. Padma’s case, they were suspended for not following procedure on detaining women in the police station and not for torture. The Police have been negligent by delaying victims of police brutality adequate medical attention that further worsened their condition and eventually led to their death. Deaths of persons in the custody of the State is an institutional failure. As the TNSHRC recently noted in the P. Ramkumar case, “The prisoner was in the care and custody of the State. Therefore, it was the bounden duty of the prison officials to ensure safety and security of the prisoner in their custody and to ensure that he does not cause any harm to himself or anybody else.” The ability of the State to kill with impunity, denotes the suspension of the rule of law and the power of the Indian state over certain citizens. In the next essay in this series, we will discuss impunity and complicity of state and non-state institutions in cases of custodial deaths in India.

Related Posts

The obligation to deny: Accountability (or the lack thereof) in cases of custodial deaths in India – 3

In India, the value and significance of accountability stem not from what it describes and espouses, but from the lack of it. The criminal justice system skirts around the issue of accountability, its institutions often complicit in the perpetuation of violence.

In part three of this series, we analyze the types of accountabilities that take place within the various institutions that deal with custodial violence and torture in India. These institutions include the Police, the judiciary, the executive, the medical fraternity and the national and state human rights commissions. We examine the status of 15 cases of custodial deaths between 2015 and 2016, whether any compensation was provided to the victims’ families and the status of inquiries by different governmental bodies, while also highlighting independent inquiries by human rights organizations and civil society groups that have taken place in these cases. While there are gaps in our data, it is evident that accountability is rarely a concern for institutions of the State, which are bound to protect and uphold the rights of victims.

In India, the Police hardly face any legal consequences for their brutality and violence against citizens. Accountability remains a challenge because Section 197 of the Code of Criminal Procedure (CrPC) provides immunity from prosecution to all public officials unless the Government approves it. This is a provision that the central and state governments often use to avoid prosecuting officials thus making conviction in cases of custodial torture and deaths difficult.

On 3 October 2016, Minhaj Ansari and two of his friends were arrested from their village Dighari in Jamtara district, in Jharkhand. Sonu Singh, a Vishwa Hindu Parishad (VHP) leader, made the first complaint to the Police against Ansari for allegedly posting a photograph of himself with a calf on a WhatsApp group, followed by another of him posing with beef. The participants of the group found the images “obscene” and complained to the Police. After two days in police custody, Ansari was taken to a hospital in Ranchi to be treated for injuries and was eventually declared dead on 9 October 2016. A First Information Report (FIR) was registered against police officer Harish Pathak for attempt to murder, which was later changed to murder after Ansari’s death. Harish Pathak was suspended, but eventually the order was revoked after he was denied one increment. The trial against him did not begin and Pathak was able to get a stay on his case.

Sonu Singh, the VHP leader, was not present in the chargesheet filed by the Police. In 2017, Senior Advocate Abdullah Allam filed two writ petitions at the Jharkhand High Court – one for compensation and a job for Ansari’s family members and the other for an investigation by the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI) and punishment against Harish Pathak. As per news reports from 2018, the Criminal Investigation Department (CID), which is a branch of the state Police, found that Ansari was beaten after being taken to the police station and was going to file a chargesheet naming Harish Pathak under Section 304 (punishment for culpable homicide not amounting to murder) of the Indian Penal Code (IPC). In June 2020, Harish Pathak was posted in Jharkhand Chief Minister Hemant Soren’s constituency. A June 2020 news report claimed that Pathak’s suspension order was eventually revoked. The trial for the case is yet to begin at the time of writing. Speaking to news agency eNewsroom in June 2020, advocate Allam mentioned that “Pathak had registered two cases against Ansari, one for circulating the beef message and the other against the victim’s family for attacking him. So, we initially demanded that the CBI club all three FIRs and investigate the matter.” TwoCircles.net on 22 July 2020 reported that the family had received four hundred thousand rupees as compensation.

Ramkumar, from Tamil Nadu, was arrested by the Chennai Police on 2 July 2016 in connection with the alleged murder of Swathi, a 24-year-old IT professional on 24 June 2016. He died on 18 September 2016 in judicial custody in a Puzhal Central Prison – a high-security prison in Chennai. On 4 May 2020, the National Human Rights Council (NHRC) closed the file regarding Ramkumar’s custodial death stating that the complaint was not substantiated: based on the Police report, Ramkumar had been arrested on properly formed charges and there was no reason to believe that his death was not a suicide. The NHRC registered a case in March 2017 and closed it in 2020, deciding that there was “nothing on record” to indicate Ramkumar was falsely implicated or murdered.

In December 2021, the Madras High Court stayed all further proceedings on the suo motu case initiated in 2020 by the Tamil Nadu State Human Rights Commission (TNSHRC) regarding the death. The High Court stayed the proceedings based on a petition filed by R. Anbalagan, the then Superintendent of Puzhal Central Prison-II. The petitioner, who served as the superintendent of the central prison when the incident occurred on 18 September 2016, stated that the TNSHRC could not initiate the proceedings after a delay of four years as it would not have the power to condone the delay. The petitioner also noted that the report of the postmortem examination conducted by five doctors, including one from the All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS) in New Delhi, concluded that the victim appeared to have died due to electrocution. The Judicial Magistrate-II of Tiruvallur reached a similar conclusion after an investigation was conducted under Section 176 of the CrPC (investigation into deaths in police custody are to be conducted by a judicial magistrate), and the NHRC too found that the allegations leveled by Ramkumar’s parents were not substantiated by any record. On 19 September 2016, the Madras High Court also dismissed the petition filed by P. Ramkumar’s father seeking a probe by the CBI.

However, on 31 October 2022, more than six years after Ramkumar’s death, the TNSHRC recommended the Tamil Nadu government to pay a compensation of a million rupees to Ramkumar’s father within a month. The TNSHRC noted that “the Government of Tamil Nadu is also responsible for the death of Ramkumar in Puzhal Prison and hence the state is liable to pay compensation to the father of the deceased namely Paramasivan for the suspicious death of his son in the Puzhal Prison.” This recommendation was issued after considering the oral and documentary evidence produced by the TNSHRC’s Investigation Wing and witnesses. The TNSHRC said: “Suspicion arises[…] whether the prisoner Ramkumar committed suicide by electrocution due to self-inflicted joule injuries or some other person electrocuted the body of the deceased or the reason stated in the final report by the AIIMS doctor Dr. Sudhir Gupta that the deceased died due to asphyxia.”

The TNSHRC also said that it was for the prison authorities to protect and promote the human rights of the prisoner and further said it was not satisfied with the report submitted by its own Investigation Wing, as well as with the report submitted by the Judicial Magistrate and also the final report of the investigating officer in the criminal case. “The authorities, who had examined the witnesses and submitted their report, had not given any valid reason that Ramkumar committed suicide,” the Commission said. Hence, the TNSHRC was of the opinion that an independent probe is “very much essential” to find out how P. Ramkumar had actually died and recommended the State government to constitute an independent probe to find out whether Ramkumar died by suicide by pulling and biting into a live electric wire inside Puzhal prison as claimed by the respondents, or due to homicidal injury as alleged by the complainant.

Shameel Basha was picked up by the Police in connection with the missing person’s case of a former female colleague, kept in illegal detention and tortured from 15 to 18 June 2015. He died in Rajiv Gandhi Government General Hospital, Chennai, Tamil Nadu, on 26 June 2015, following health complications that he reportedly developed while he was in police custody. In Basha’s case, the Vellore Superintendent of Police V. K. Senthil Kumari said that a magisterial inquiry on the incident was opened after a case was registered under Section 176 of the CrPC. Based on the inquiry, Martin Premraj, the inspector in charge of placing Basha in custody, was transferred from Pallikonda station to the prohibition enforcement wing. This was done after Basha was admitted to hospital on 18 June. When Basha died on 26 June, Premraj was on medical leave. Two days later, Premraj and six other policemen from the Pallikonda station were placed under suspension. Premraj was absconding when asked to appear before the Crime Branch-Central Intelligence Department office in July 2015. In November 2016, Premraj’s writ petition was submitted before the Madras High Court asking for his suspension to be revoked as he had been suspended for more than three months and had not received any chargesheet. In response to this, the High Court directed that Premraj be placed in some other non-sensitive post. The Government paid Rs. 500,000 to the kin of the victim and provided proof of payment to the NHRC, which closed the complaint as a result.

Meenkulambu Karthik was picked up by the Police for a robbery in Chennai, Tamil Nadu, on 19 September 2016. He died on 21 September 2016, when he was rushed to the hospital as he complained of breathlessness. The hospital authorities said that he was brought dead. A fact-finding probe launched by the Communist Party of India – Marxist (CPIM) into his custodial death indicted the Chennai police of Karthik’s murder. The fact-finding team urged the Uthiramerur magistrate to record the statements of the co-suspects who were witness to Karthik’s torture in illegal custody besides registering a murder case against the police officials. The probe established that the victim was under custody from 19 September until his death on 21 September 2016. The Police paid Rs. 200,000 to the family which, according to the fact-finding probe, substantiated the fact that Karthik was killed in police custody. The Chennai Police had not acted on the petition filed by Karthik’s mother, and the CPIM probe highlighted the manufactured claims of the Police that Karthik and his friend A. Arunachalam had figured in the CCTV footage in which a woman software professional was robbed in Thuraipakkam. The probe alleged that the officials had resorted to custodial torture only after they had learned that Karthik belonged to a Scheduled Caste group. Hence, the Police’s attribution of suspicion was not accepted. The doctors who were part of Karthik’s autopsy admitted in the death report that the body had aberrations on both thighs, “a scar on the right clavicle area [and] multiple bruises.” The CPIM team noted that, “The namesake suspension of the lower rung cadre would not be enough. The personnel from Kannagi Nagar, Semmenjeri, Thuraipakkam and Neelankarai Police stations should be subjected to identification parade before Arunachalam and four other youth, also from Chinthadripet, who were detained illegally along with the deceased. The men were also subjected to custodial torture.” The fact-finding team also demanded that the jurisdictional Deputy Commissioner of Police (DCP) and the Assistant Commissioner of Police (ACP) be placed under suspension for the custodial violence besides transferring the investigation to the CBI and initiating prosecution for bribing the family with Rs. 200,000. Karthik’s family returned the amount three days after his death. This was the first installment of the Rs. 400,000 promised by a police officer. According to reports, they were “forced to keep the custodial violence under wraps”.

Kuppuswamy was a small shop owner who was arrested on 15 August 2016, for illegal liquor sale. He was subsequently lodged in Madurai Prison (Tamil Nadu) under judicial custody and died on the same day. Kuppuswamy’s family members refused to believe the police version of events which claimed that Kuppuswamy had died due to illness, and staged a dharna (protest) in front of the Sanarpatti police station. They also accused the cops of arresting him in a false case. The NHRC complaint filed by the Superintendent of Prisons, Central Prison, Madurai, one day after Kuppuswamy’s death was closed as the TNSHRC intimated the NHRC in October 2016 that they have taken cognizance of the matter. At the time of writing, no further updates are known regarding this case.

Mohan, a Sri Lankan national in his early forties, was picked up by the Police in Tamil Nadu in an alleged fake passport racket case. According to reports, Mohan was taken into custody and interrogated for three days. While he was being questioned on the night of 4 September 2015, he collapsed and was admitted to a nearby private hospital where he was declared dead. A case under Section 176 CrPC was registered and referred for judicial inquiry. A friend of Mohan’s said that the Police managed to get in writing from Mohan’s partner that he had died of cardiac arrest. They also promised monetary compensation and a job for her eldest son. At the time of writing, no further updates are known regarding this case.

Gokulakannan was a contract laborer who was picked up around midnight by the Police in connection with a murder, and later rushed to hospital in Salem, Tamil Nadu, where he was declared “brought dead.” He died on 6 June 2015. According to reports, local activists said that the Police threatened and bribed the family to take back allegations of custodial torture. Tamil Nadu People’s Rights Movement alleged that senior police officials had forced the family members to accept Rs. 1,200,000 to silence them. “Gokulakannan’s family members were threatened by the Police and forced to accept the money. His family admitted it to us when our team spoke to them.” Gokulakannan’s mother confirmed the same to a news portal. “They warned us of dire consequences if we pursued the case. We didn’t have any option but to accept the money.” Three police officers, including a sub inspector, were also suspended, for negligence of duty and for picking up a man for interrogation while he was unwell.

Bujji was detained for his role in the killing of a police constable in Tamil Nadu. He died a few hours after he was taken into police custody, on 15 June 2016. The Police denied that Bujji’s death was a custodial murder and said that he had died as a result of heart attack. The National Confederation of Human Rights Organizations (NCHRO) and other activist organizations sought the suspension of the police personnel involved in Bujji’s death. The Tamil Nadu Chief Minister Jayalalitha had initially announced an aid of Rs. 500,000 for the family of the constable Bujji was accused of stabbing, but later revised the amount to Rs. 10,000,000.

On 21 March 2015, Sheikh Hyder was arrested for an alleged bicycle theft and died the same day in a police station in the state of Telangana. The State Minorities Commission in Telangana ordered a probe by a four-member committee. The probe found that it was a case of custodial death and recommended that action should be taken against responsible police officers and doctors. The local district collector ordered an Executive Magistrate inquiry into Hyder’s death in clear violation of Section 176 of the CrPC. The Executive Magistrate’s report used the Police description of Hyder’s injury verbatim. In March 2015, following public attention in the matter, the inspector and a head constable of the police station where Hyder was arrested were suspended. The Andhra Pradesh SHRC (the SHRC for Telangana state had not yet been set up in 2015) took cognizance of the matter on 1 April 2015. The Police submitted its report on the case to the Andhra Pradesh SHRC in April 2015. Even though activists criticized it for being misleading and poorly written, the report did admit that Hyder’s death was caused by police negligence. A 2016 Human Rights Watch report, which conducted an in-depth investigation into Hyder’s case, mentioned that his family alleged abuse, but the Police did not file an FIR against the police officials implicated in arresting and torturing Hyder. It was also found that both the SHRC and the minority commission had investigated the death and recommended that the state government pay compensation to the family. However, the family had not received any compensation at the time of writing.

Viqaruddin Ahmed was a suspect in the Mecca Masjid bombing in which two policemen died in Hyderabad. The Police killed Ahmed and four others in an “encounter” near Alair in Telangana on 7 April 2015 while 17 policemen escorted him to the Hyderabad Court from Warangal Jail. Ahmed had previously expressed concern that he would be abused on the way to or from prison by the Police. In April 2012, his father had also filed a complaint mentioning that he feared for his son’s life. Ahmed was first arrested in 2010 and was accused of forming a militant group that targeted police officers. Gulam Rabbani, the lawyer representing Ahmed’s father, stated that no criminal report was recorded when he tried to register a complaint regarding Ahmed’s alleged murder. Rabbani then filed a court case demanding that charges of murder should be filed against the Police. Although the case was admitted in Court, and Rabbani said that according to procedure, a hearing should have taken place in the first week of June 2015, the hearing did not take place. Speaking to AlJazeera in 2015, Ahmed’s father claimed that the Police was waiting for an opportunity to murder his son.

While there are discrepancies in how police custody is defined in the law, according to a 1980 Supreme Court judgment, police custody includes being taken to jail in the custody of the Police. Going by this definition, Ahmed’s case would be a clear case of death while in police custody. However, the details regarding the location of the death have not been included in the NCRB Crime in India reports after 2014. Therefore, from the NCRB data it cannot be ascertained where the victim died which is a useful detail to have especially when fighting legal cases.

The fact finding report conducted from 12 to 14 April 2015 by Civil Liberties Monitoring Commission (CLMC), a Hyderabad-based human rights organization stated that in Ahmed’s case the Alair Police had filed a case against the deceased under Section 307 of the IPC (attempt to murder), but did not file a case against the Police personnel involved in the killing under Section 302 of the IPC (punishment for murder).

A Special Investigation Team (SIT) comprising six police officials was formed on 13 April 2017 to inquire into the matter and the NHRC took cognizance of the matter as well. In April 2018, the SIT was yet to submit its report, according to TwoCircles.net. The NHRC found violation of rights and torture and requested a compensation of Rs. 500,000 to the surviving family members of the accused. The last hearing in this case was on 16 July 2020 and the matter was disposed of as completed. “Although the NHRC directed the Government to pay compensation to the victims’ families, unfortunately the Government has not complied with the orders of the NHRC and till date no compensation money has been released to the victims’ families,” CLMC director Lateef Khan told us via email. No judicial magistrate inquiry was ordered or conducted in this matter even though it is a statutory requirement under Section 176 of the CrPC.

On 29 April 2015, the Executive Magistrate of Nalgonda District, under whose territorial jurisdiction the encounter had taken place, was appointed by the Telangana government to preside over the magisterial inquiry despite the fact that a government order was issued in clear violation of Section 176 of CrPC (that only authorizes the judicial magistrate to inquire into custodial deaths). CLMC filed a writ petition in the High Court (Writ Petition number 12453/2015) demanding a judicial magistrate inquiry, but it did not uphold this statutory requirement and the matter still stands as sub judice. “Two writ petitions have been pending in the high court for the past seven years but the matter has been put in cold storage and since 2015 no hearing was conducted in this matter in the high court,” added Khan. An executive magistrate inquiry headed by a government cadre revenue officer was conducted three months after the encounter: it gave a clean chit to the police officer involved and did not find any police fault or excessive use of force.

In G. Bonappa’s case the Police claim that he was inebriated during the Bonalu festival, was dancing with a procession in Hyderabad and was picked up on 2 August 2015 after he got into a fight with a home guard. He died the following day on 3 August 2015. Bonappa’s family, however, alleged that the Police had brutally beaten him up. “When we took him home, he was not able to eat or drink. He was exhausted and appeared uneasy. We took him to the police station and asked them what had happened. They responded very rudely and abused us. Later, they sent constables with us to take him to hospital. He died on the way,” Bonappa’s cousin told Deccan Chronicle on 4 August 2015. G. Arjuna, the victim’s brother, claimed that Bonappa was in good health before he was arrested. However, after the Police released him, Bonappa was exhausted and half-conscious and his throat, legs and hands were swollen. “He could not speak. The Police had beaten him up for many hours causing internal injuries,” Arjuna said. Hyderabad Police commissioner Mahender Reddy ordered a probe on 5 August 2015 into the death of Bonappa. A team from the Central Crime Station in Hyderabad had taken up the investigation after booking a case under Section 174 of the CrPC (death by suicide or suspicious death). According to an 8 August 2015 news report in Deccan Chronicle, two sub inspectors involved in the case were removed from the police station and attached to the headquarters pending an inquiry into Bonappa’s death.

Padma was called in for questioning on 21 August 2015 to the Asifnagar police station in Hyderabad, Telangana, in connection with a theft case. She was called for questioning when she was sick, and called in again the next day on 22 August, when she collapsed and died, according to the Police. In Padma’s case, seven police officers – the Asifnagar police station inspector, a sub inspector, an assistant sub inspector, one head constable and three constables – were suspended in the interests of a fair inquiry and for gross negligence in keeping her during odd hours resulting in severe health complications, which ultimately resulted in her death in the hospital. The SHRC took cognizance of the case and requested detailed reports from the Hyderabad Commissioner and the hospital where Padma died. A preliminary inquiry conducted into Padma’s death revealed that the Asifnagar police personnel did not inform their superior officers about detaining three women as part of the probe into the theft case, nor did they take into account Padma’s medical condition before questioning her. “As a procedure, the policemen should inform their superiors when they detain or take women into custody in any case. But, in this case they did not do so. As a result, the woman collapsed during questioning by the Police and died some hours later at a hospital,” an official, who conducted the investigation, said.

Lakshman was accused in a murder case and was arrested by the Pulkal Police in Medak district,Telangana. On 12 March 2015, Lakshman died while the Police were taking him to the hospital. In Lakshman’s case four policemen – inspector V. Nagaiah, sub-inspector Lokesh and two escort constables, Yadaiah and Uday – were suspended for negligence of duty. A magisterial inquiry was ordered as well. The superintendent of Police at Medak mentioned that they registered a case under Section 176 of the CrPC (inquiry into the death of any person while in police custody) in connection with the incident. Lakshman’s family and local villagers alleged that this was a case of police brutality and they suspected foul play. At the time of writing, the report from the magisterial inquiry was not accessible and the NHRC does not have records of this case.

Obaidur Rahman was arrested by the West Bengal police in a criminal case arising out of a land dispute with his neighbor. Rahman died in police custody in Malda, West Bengal, within 24 hours of his arrest, on 21 January 2015. No judicial magisterial inquiry – which is mandatory in all cases of custodial deaths – was held in Rahman’s case. An executive magistrate initiated an inquiry and filed the report in January 2015. However, this was a blatant miscarriage of the rules stipulated in cases of custodial deaths. MASUM’s secretary and national convenor, Kirity Roy, filed a complaint with the NHRC requesting that a judicial magistrate inquiry would be carried out.

Letter of Complaint to the NHRC requesting that a judicial magistrate inquiry be carried out in Obaidur Rahman’s case. Source: Mr. Kirity Roy, MASUM, West Bengal.

As per the 2016 Human Rights Watch report, Rahman’s family alleges that when his condition continued to deteriorate in the Malda hospital, the doctors there suggested that he be taken to a hospital in Kolkata but the Police refused. So the family wrote to the Superintendent of Police requesting a transfer for further care. Following the letter, police personnel took Rahman to the Bangur Institute of Neurosciences, Kolkata, where he was declared dead on arrival. The post-mortem determined that no internal or external injuries could be detected and that Rahman died because of brain stem hemorrhage due to a cerebrovascular accident – the medical term for a stroke. The post-mortem report was signed by the same sub inspector against whom the family had filed a complaint. The family also told Human Rights Watch that they faced harassment and intimidation after his death. The NHRC took cognizance of the matter (image below): “The Investigation Division after analyzing the various reports has suggested closing of the case as there is no foul play or negligence on part of the police officials and the death was natural and due to illness. The Commission also independently considered the various reports and suggestions made by the Investigation Division and found no reason to differ with the suggestions of the Investigation Division”, thereby closing the case on 5 December 2017.

Action taken by the NHRC in Obaidur Rahman’s case. Source: Mr. Kirity Roy, MASUM, West Bengal

Bhushan Deshmukh was arrested under the Arms Act for possession of illegal weapons on 20 September 2015 in Kolkata, West Bengal. Burtolla Police claimed he died of diarrhea, but a post-mortem report revealed multiple injuries all over the body, suggesting that he was beaten up by more than one individual. It was later found that Deshmukh was actually arrested on 19 September 2015, a day before police records show, and was taken to a private hospital by the Police in violation of protocol on 24 September 2015. Deshmukh died in hospital the following day on 25 September 2015 night. The officer-in-charge of Burtolla police station, the night duty officer, lock-up in charge and a constable present the night when Bhushan was beaten up by the Police, were suspended on 4 October 2015. A departmental probe was ordered against the four officers by registering a case of culpable homicide. The Metropolitan Magistrate, Kolkata, found that Bhushan died due to inflicted injuries and torture in police custody. The West Bengal SHRC took cognizance of the matter on 5 October 2015 and found that Deshmukh was left untreated for more than five hours in the lock-up after he started vomiting. The SHRC requested a compensation of Rs. 200,000 for the deceased’s family and ordered a departmental inquiry against police personnel involved in the case: sub inspector Pradip Kumar Rakshit, Bikash Biswas and Constables Hrikesh Mondal and Partha Sarathi Mondal. Sub inspector Bikesh Biswas, the investigating officer in the matter, was held primarily responsible by the inquiry. Importantly, the SHRC recommended that a Standard Operating Procedure be put in place regarding the duties of the Police when taking suspects into custody. The NHRC confirmed that the deceased had died due to torture in police custody and directed that Rs 500,000 compensation should be paid to the kin of the deceased. As of August 2018, proof of payment was submitted to the NHRC and the matter was closed.

While compensation to the families is important, it is also worth questioning whether the lives of victims of police torture, who are mostly young men and breadwinners, are worth just 200,000 or 400,000 rupees. While the moral implications of putting a value on a person’s life are always questionable, there are also inconsistencies on how the amount of the compensation is decided.

One challenge for accountability in custodial deaths is the propensity of government doctors to back police claims. Autopsy and forensic reports frequently support the Police version of events even where there is no apparent basis. Often, medical professionals conducting the autopsy and writing postmortem reports are under significant pressure from police officials to produce outcomes favorable to them. For example, in Obaidur Rahman’s case, the sub inspector against whom a complaint of torture was filed was also the one who signed the postmortem report.

Third degree methods are used as a euphemism for police torture in India. Writing in 1995, Amar Jesani outlined the relationship between medical ethics and police violence. Jesani’s paper lists reasons for doctors to remain silent when they encounter cases where the victim has been tortured by the Police. One reason is that most doctors are unaware of the correct medical procedures and codes of conduct, or doctors try to maintain the status quo due to their personal beliefs and biases. Socio-economic backgrounds play an influential role when it comes to viewing victims as criminals and as deserving of torture at the hands of the Police. In such cases, doctors remain silent and avoid reporting on instances of custodial violence and torture. The lack of training and care by medical professionals working in institutions closely associated with the Police and prisons leads to an increase in custodial deaths as well, as highlighted in a report by journalist Sukanya Shantha on prison conditions.

Every case of custodial death is supposed to be reported to the NHRC. The Police are required to send the findings of the magistrate’s inquiry to the NHRC along with the post-mortem report. The NHRC also calls for the autopsy to be filmed and is empowered to summon witnesses, order production of evidence and recommend that the government initiate prosecution of officials. However, in practice, its recommendations have mostly been limited to calling on the Government to provide compensation money to victims’ families or other immediate interim relief. Providing adequate and timely compensation to the victims’ families is important since most victims of custodial deaths are poor, young men, who were often the sole breadwinners in their families. Further, the compensation money ensures that the families have a chance at fighting long legal cases to ensure those who are responsible are brought to justice. However, as discussed, we found cases where the victims’ families have not received the ordered compensation money.

The SHRC is a recommendation body that was set up to investigate, promote and protect human rights at the state level in India. Anthropologist Ather Zia, in Resisting Disappearance: Military Occupation and Women’s Activism in Kashmir (2019), notes that while “the Government presents the SHRC as a major watchdog institution for safeguarding human rights, it remains a recommendation body and cannot penalize anyone. As it has no power of adjudication, the SHRC is seen as a “toothless tiger”.” (page 38)

The national and state human rights commissions have largely failed in their oversight role in cases of custodial killings. While the NHRC has a responsibility to seek both justice and relief for victims’ families by recommending prosecution of those who committed the crime and compensation for the victims, seeking prosecution often jeopardized the possibility of relief. “The two sadly should have gone together but they tended to clash,” Satyabrata Pal told HRW for their 2016 report on custodial deaths. “Most states would simply not accept the recommendation and therefore, since NHRC can only recommend and not compel, we would then fail in our duty to get both justice and relief.” There are also instances in which the NHRC closed cases without even recommending compensation, leaving the matter to the state government. Between April 2012 and June 2015, of the 432 cases of deaths in police custody reported to the NHRC, the commission recommended monetary relief of about Rs. 22.91 million (USD 343,400), but recommended disciplinary action in only three cases and prosecution in none. Similarly, the People’s Union for Democratic Rights (PUDR), a civil society organization working on human rights in India, notes that the role of the NHRC has been relegated to that of making recommendations in cases of custodial deaths. “The number of cases pending with the NHRC brings out the limitations of the commission as a mere elephant in the room,” highlighting the role of the NHRC as opposed to its intention of being an effective legal remedy when it was envisioned in 1993.

From the NCRB data on custodial deaths, it was found that 452 deaths were reported in custody between 2014 to 2018, but only 192 cases were registered, 118 policemen were charge-sheeted and no police personnel were convicted during this period. In some cases, investigation into custodial deaths is conducted by the same crime branch under which the police station falls and so the investigators will try their best to help their colleagues rather than conduct a fair and impartial investigation. As noted in part one of this series, there is a lack of political will to implement legal frameworks and measures proposed by international and Indian legal scholars. This lack of political will often leads to limited accountability for police personnel as perpetrators of torture and brutality against citizens. In a rare and important ruling in January 2016, the sessions court in Mumbai convicted four police constables of culpable homicide for the brutality that lead to 20-year-old suspect Aniket Khicchi’s death in custody in 2013. The constables were faced with seven years in prison; however, three of the four police constables were granted bail in June 2018 pending their appeal against the conviction which was to be decided by the High Court. As the 2016 Human Rights Watch report notes, “police abuse reflects a failure by India’s central government and state governments to implement accountability mechanisms. Despite strict guidelines, the authorities routinely fail to conduct rigorous investigations and prosecute police officials implicated in torture and ill-treatment of arrested persons.”

As is evident from the case details, there have been no convictions or arrests of police personnel involved. In some cases, formal complaints were not even registered against police personnel for torture, whereas the evidence points to the contrary. Even when police personnel were suspended, as in N. Padma’s case, they were suspended for not following procedure on detaining women in the police station and not for torture. The Police have been negligent by delaying victims of police brutality adequate medical attention that further worsened their condition and eventually led to their death. Deaths of persons in the custody of the State is an institutional failure. As the TNSHRC recently noted in the P. Ramkumar case, “The prisoner was in the care and custody of the State. Therefore, it was the bounden duty of the prison officials to ensure safety and security of the prisoner in their custody and to ensure that he does not cause any harm to himself or anybody else.” The ability of the State to kill with impunity, denotes the suspension of the rule of law and the power of the Indian state over certain citizens. In the next essay in this series, we will discuss impunity and complicity of state and non-state institutions in cases of custodial deaths in India.

SUPPORT US

We like bringing the stories that don’t get told to you. For that, we need your support. However small, we would appreciate it.