The new tools for India’s age-old extraction, destruction and disappearance of Bastar’s forests

In the month since we published the report on the civilian killings in Bastar, there have been two more rounds of anti-Naxal encounter operations in the region, reportedly killing 16 Maoists and one constable. In early June, a 25-year-old activist named Sunita Pottam was reportedly dragged out of her house, assaulted, and arrested in relation to multiple cases. Human-rights defenders engaged in peaceful campaigns against corporatisation and militarisation in the region have been arrested and subject to violence, such as Surju Tekam, Shankar Kashyap, Oram Samlu Koram, Lakhma Koram, and Ranu Podyam. At the centre of the state’s targeting of these individuals and the surge of killings in the region, is the ongoing disappearance of land in Bastar.

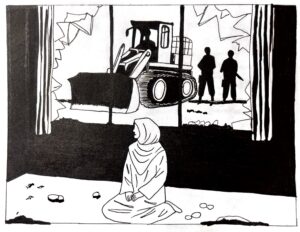

Maase Sodi was attending a protest against the destruction of their forest lands for a road-construction project when security forces shot her, killing her six-month-old daughter whom she was holding at the time. The reckless rise in recent violence in Bastar is supported by laws that facilitate the easy exploitation of its land, and securitisation that paves the way for acts such as aerial bombings that wreak large-scale destruction. Under the Narendra Modi government, the Indian state has found new tools to justify the disappearance of Bastar’s lands, while relying on the same old narrative of security and development.

To understand this state-sanctioned disappearance of Bastar’s land and people, it is worth contextualising the present-day developments in the region’s history. In Subalterns and Sovereigns, Nandini Sundar examines the impact of British land reforms on the indigenous people of Bastar. In the late 19th century, the colonial administration introduced changes that disrupted traditional land ownership and management systems, resulting in the alienation of indigenous communities from their land. The British implemented a land-revenue system requiring formal ownership and taxation, a concept foreign to the communal ownership and customary rights practised by the indigenous population. Extensive survey and settlement operations were conducted to document land ownership, often disregarding traditional rights and practices. This led to the breakdown of communal land-holding patterns, and many indigenous people, unable to prove formal ownership under the new legal standards, faced dispossession.

Additionally, the British enforced stringent forest laws to control and exploit forest resources for commercial purposes, such as the extraction of timber. These laws restricted indigenous communities’ access to forests, limiting their ability to gather produce, hunt, and practice shifting cultivation. To further their economic interests, the British also promoted cash crops and commercial agriculture, conflicting with the subsistence farming of indigenous communities. This shift not only altered the local economy but also caused environmental degradation, further disrupting the indigenous way of life. The creation of large reserved forests barred indigenous communities from accessing these areas or severely restricted their activities, exacerbating their marginalization and loss of livelihood.

With India transforming into a modern nation-state in the 20th century, and engendering sovereignty into the logics of its functioning, the indigenous communities were pushed to the periphery for exploitation. In many places, the exploitation was met with resistance. Sundar takes the conversation further in Civil Wars in South Asia: State, Sovereignty, Development, in which she documents how conflicts in the region have historically been intertwined with issues of state sovereignty and developmental agendas. Civil wars and resistances within Bastar cannot be understood solely as local or isolated conflicts; instead, they are deeply rooted in the broader historical and political processes of state formation, economic development, and the assertion of modern state sovereignty.

State-led development projects and the imposition of modernity often clash with the traditional ways of life and the sovereignty of indigenous communities. This conflict is particularly evident in regions like Bastar where the state aims to integrate marginalised areas through infrastructure projects, resource extraction, and the extension of administrative control. These development initiatives, while often framed as progress, leads to displacement, loss of livelihoods, and the erosion of indigenous cultures, thereby fuelling resistance and conflict.

The disappearance of land witnessed in Bastar today stems from the same, age-old motivation of exploitation of resources—now, it is the Indian state and its oligarchs who have set their sights on these forests. What is new, however, is the technological advancement of recent years and the destruction it enables; the securitisation of the deprivation in the region to justify the indiscriminate use of force; and the building of pipelines for a select few to accumulate capital.

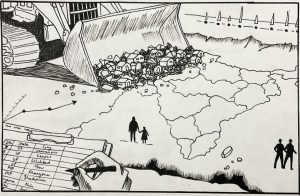

In December 2016, the Indian government approved the Road Connectivity Project for Left Wing Extremism Affected Areas (RCPLWEAA), which seeks to ensure all-weather road connectivity in 44 districts, including 35 that it deems worst affected and nine adjoining districts. The project has sanctioned the construction of a total of 291 roads in Chhattisgarh, across a total length of nearly 2,500 kilometres, less than half of which was completed as of 2021.

In May 2017, the defence minister Rajnath Singh announced the introduction of a new doctrine to combat Left Wing Extremism called Operation Samadhan. Singh described samadhan, which translates to solution, as a backronym in which the S stood for “Smart Leadership,”; A for “Aggressive Strategy”; M for “Motivation and Training”; A for “Actionable Intelligence”; D for “Dashboard based KPIs (Key Peformance Indicators) and KRAs (Key Result Areas)”; H for “Harnessing Technology”; A for “Action plan for each theatre”; and N for “No access to financing.”

The previous Disappearance Project article on Bastar documented this aggressive strategy and the reckless killing of civilians that it has led to under the new Bharatiya Janata Party government in Chhattisgarh since last December. Singh’s aggressive strategy, however, also includes “Aggression in development and Aggression in road construction.” As part of the aim to harness technology, Singh noted that the use of Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs), or drones, were “sub-optimum” and needed to be “augmented both by numbers and by use in the right place.”

The past three years has seen an indiscriminate implementation of this technology, with the increased use of aerial attacks. On 19 April 2021, the villages of Botalanka and Palagudem experienced the first wave of aerial attacks, with villagers claiming at least 12 bombs were dropped on houses in the region. Almost exactly a year later, on the intervening night of 14 and 15 April 2022, locals accused security forces of another wave of drone bombardments that struck the villages of Bottethong, Mettaguda, Duled, Sakler, and Pottemangi, in Chhattisgarh’s Bijapur and Sukma districts. In January 2023, a third wave of aerial attacks took place, targeting Mettaguda and Bottethong again, as well as Errapalli village in Bijapur. Just two months later, the Bastar region witnessed its fourth drone bombing, in Bijapur’s Bhattiguda village. Each time, despite eyewitness accounts and villagers displaying shells of the bombs fired upon them, security forces denied the attacks.

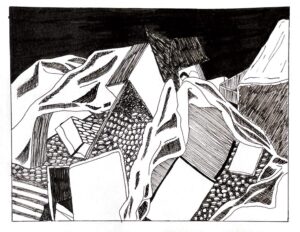

The latest such attack took place earlier this year, on the night of 7 April, as police, paramilitary, and military forces converged on the villages and forests of Palaguda, Ittaguda, Jilorgada, Gommaguda, and Kanchal, in the Bijapur and Sukma districts. The operation began at 11.45 pm and lasting roughly half an hour, unleashed a barrage of destruction. According to Moolvasi Bachao Morchha—or Platform to Save the Original Inhabitants, a local civil-society organisation—the security forces deployed rocket launchers and drone bombs during the attacks. With over 30 high-explosive bombs fired, the attack decimated swathes of forest land, obliterating trees, plants, and wildlife within a 100-200 square meter radius. Many villagers narrowly escaped death, fleeing for their lives amid an atmosphere thick with smoke, fear and terror.

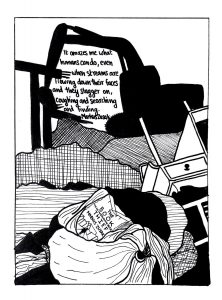

The timing of these attacks, each April for three consecutive years, is particularly devastating because it coincides with the peak of the Mahua harvest season. Mahua flowers, a crucial source of income for the tribals, require protection from wild and domestic animals. To safeguard their livelihood, people sleep under Mahua trees, spending most of their time in the forests. The bombings have disrupted this important activity, stripping them of their ability to collect forest produce, destroying the forests and their livelihoods, and pushing their already precarious existence further to the edge.

Under Modi, the central government has also been able to push through laws that circumvent legal hurdles to the clearance of forest lands, such as the consent of local tribal communities. After a decade of pushback from the tribal ministry, which predated the Modi government, the forest ministry issued the Forest Conservation Rules of 2022, which transfer the responsibility from the central to state governments to recognise tribal rights to traditional forestlands. The rules enable the central government to authorise forest clearing without prior consultation with inhabitants, compelling state governments to obtain consent from tribal and other forest-dwelling communities. Moreover, the rules allow the central government to authorise any forest clearance before the state government obtains the consent of the forest dwellers, effectively subverting the protections granted to them under the Forest Rights Act of 2006.

The Mines and Minerals Act of 2023, in conjunction with the union budgets for 2023-2024 and 2024-2025, serve as a revealing apparatus of biopolitical control. These legislative and fiscal measures demonstrate that the allocation of taxes to coal and mining by Indian states is not geared towards national development but is rather appropriated by a select oligarchy of financial capitalists. This appropriation not only encumbers the populace with oppressive debts but also exacerbates their economic and ecological vulnerability. Herein, the state’s fiscal policies become instruments for the perpetuation of systemic inequalities.

The enclosure of Bastar happens not only through laws and bills passed in the parliament, but also through discourse production in mainstream fiction that collude to exacerbate vulnerabilities that can be exploited. It is no surprise, then, and hardly coincidental, that the propaganda film “Bastar: The Naxal Story” was released in the midst of an election cycle and heightened security operations.

This film presents a violent distortion of the Salwa Judum militia and the Supreme Court’s declaration of its unconstitutionality. Its impact, however, is far more sinister. The film obfuscates the historical narratives of civil wars and indigenous resistance against the encroachments of mining corporations and developmental projects, through a warping of identities.

The film opens with a potent image: a Brahmin man, isolated in the deep forests, succumbs to the violence of a Maoist insurgent. This scene not only amplifies the portrayal of violence against settler Brahmins in Bastar, but does so by stripping any semblance of agency from the Adivasis, who are the actual guardians of the land. The film proceeds to dehumanise the Adivasis, reducing them to mere instruments of a “revolution.” A particularly telling scene depicts a female guerrilla fighter in an act of gluttony, starkly contrasted with the portrayal of the Brahmin mother or the sorrowful, modest mothers who nourish their children. It is a striking example of how cinema can manipulate empathy and moral alignment. The film not only provides an escape but actively reshapes viewers’ understanding of their place in the socio-economic hierarchy, masking colonialism and systemic issues with the allure of nationalist pride and progress, manufacturing acquiescence to the disappearance of people and lands.

The repression in Chhattisgarh reflects a broader pattern of violence and criminalization of indigenous and Dalit communities across India, particularly those advocating for their land rights and environmental protection. Villagers protest roads and development because these projects are wreaking havoc on their crops. In Aamdai Ghati, mining companies wash iron and coal, causing significant agricultural destruction. People of Dongar are particularly affected, as their crops are ruined by these activities. Contaminated water sources lead to livestock deaths, and drilling operations by corporations cause widespread respiratory issues among villagers. The hinterlands’ people now understand that roads do not mean progress for them but instead for the oligarchs and politicians.

The targeting of peaceful indigenous movements such as the Morohnar Jan Andolan and Orcha Jan Andolan, which resist mining projects and demand the implementation of protective laws, aims to silence their human rights work through fabricated charges and severe state violence. This crisis underscores the ongoing struggle of India’s Adivasi communities against marginalization and rights violations.

The erasure of Adivasi lands through corporate mining and militarisation results in the displacement, marginalisation, and physical and cultural destruction of their communities. In Bastar, bodies are made to disappear, forests to be obliterated, minerals to be spooled for the oligarchs and politicians, sustaining the survival of the colonial logic of the state.

(Photo caption: A protest by Adivasi women with their tools in the Orcha block of Chhattisgarh’s Naraynpur district. In recent months, the Bastar region has witnessed numerous protests against road construction, mining and civilian killings. PHOTO BY BHUMIKA SARASWATI.)

Related Posts

The new tools for India’s age-old extraction, destruction and disappearance of Bastar’s forests

In the month since we published the report on the civilian killings in Bastar, there have been two more rounds of anti-Naxal encounter operations in the region, reportedly killing 16 Maoists and one constable. In early June, a 25-year-old activist named Sunita Pottam was reportedly dragged out of her house, assaulted, and arrested in relation to multiple cases. Human-rights defenders engaged in peaceful campaigns against corporatisation and militarisation in the region have been arrested and subject to violence, such as Surju Tekam, Shankar Kashyap, Oram Samlu Koram, Lakhma Koram, and Ranu Podyam. At the centre of the state’s targeting of these individuals and the surge of killings in the region, is the ongoing disappearance of land in Bastar.

Maase Sodi was attending a protest against the destruction of their forest lands for a road-construction project when security forces shot her, killing her six-month-old daughter whom she was holding at the time. The reckless rise in recent violence in Bastar is supported by laws that facilitate the easy exploitation of its land, and securitisation that paves the way for acts such as aerial bombings that wreak large-scale destruction. Under the Narendra Modi government, the Indian state has found new tools to justify the disappearance of Bastar’s lands, while relying on the same old narrative of security and development.

To understand this state-sanctioned disappearance of Bastar’s land and people, it is worth contextualising the present-day developments in the region’s history. In Subalterns and Sovereigns, Nandini Sundar examines the impact of British land reforms on the indigenous people of Bastar. In the late 19th century, the colonial administration introduced changes that disrupted traditional land ownership and management systems, resulting in the alienation of indigenous communities from their land. The British implemented a land-revenue system requiring formal ownership and taxation, a concept foreign to the communal ownership and customary rights practised by the indigenous population. Extensive survey and settlement operations were conducted to document land ownership, often disregarding traditional rights and practices. This led to the breakdown of communal land-holding patterns, and many indigenous people, unable to prove formal ownership under the new legal standards, faced dispossession.

Additionally, the British enforced stringent forest laws to control and exploit forest resources for commercial purposes, such as the extraction of timber. These laws restricted indigenous communities’ access to forests, limiting their ability to gather produce, hunt, and practice shifting cultivation. To further their economic interests, the British also promoted cash crops and commercial agriculture, conflicting with the subsistence farming of indigenous communities. This shift not only altered the local economy but also caused environmental degradation, further disrupting the indigenous way of life. The creation of large reserved forests barred indigenous communities from accessing these areas or severely restricted their activities, exacerbating their marginalization and loss of livelihood.

With India transforming into a modern nation-state in the 20th century, and engendering sovereignty into the logics of its functioning, the indigenous communities were pushed to the periphery for exploitation. In many places, the exploitation was met with resistance. Sundar takes the conversation further in Civil Wars in South Asia: State, Sovereignty, Development, in which she documents how conflicts in the region have historically been intertwined with issues of state sovereignty and developmental agendas. Civil wars and resistances within Bastar cannot be understood solely as local or isolated conflicts; instead, they are deeply rooted in the broader historical and political processes of state formation, economic development, and the assertion of modern state sovereignty.

State-led development projects and the imposition of modernity often clash with the traditional ways of life and the sovereignty of indigenous communities. This conflict is particularly evident in regions like Bastar where the state aims to integrate marginalised areas through infrastructure projects, resource extraction, and the extension of administrative control. These development initiatives, while often framed as progress, leads to displacement, loss of livelihoods, and the erosion of indigenous cultures, thereby fuelling resistance and conflict.

The disappearance of land witnessed in Bastar today stems from the same, age-old motivation of exploitation of resources—now, it is the Indian state and its oligarchs who have set their sights on these forests. What is new, however, is the technological advancement of recent years and the destruction it enables; the securitisation of the deprivation in the region to justify the indiscriminate use of force; and the building of pipelines for a select few to accumulate capital.

In December 2016, the Indian government approved the Road Connectivity Project for Left Wing Extremism Affected Areas (RCPLWEAA), which seeks to ensure all-weather road connectivity in 44 districts, including 35 that it deems worst affected and nine adjoining districts. The project has sanctioned the construction of a total of 291 roads in Chhattisgarh, across a total length of nearly 2,500 kilometres, less than half of which was completed as of 2021.

In May 2017, the defence minister Rajnath Singh announced the introduction of a new doctrine to combat Left Wing Extremism called Operation Samadhan. Singh described samadhan, which translates to solution, as a backronym in which the S stood for “Smart Leadership,”; A for “Aggressive Strategy”; M for “Motivation and Training”; A for “Actionable Intelligence”; D for “Dashboard based KPIs (Key Peformance Indicators) and KRAs (Key Result Areas)”; H for “Harnessing Technology”; A for “Action plan for each theatre”; and N for “No access to financing.”

The previous Disappearance Project article on Bastar documented this aggressive strategy and the reckless killing of civilians that it has led to under the new Bharatiya Janata Party government in Chhattisgarh since last December. Singh’s aggressive strategy, however, also includes “Aggression in development and Aggression in road construction.” As part of the aim to harness technology, Singh noted that the use of Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs), or drones, were “sub-optimum” and needed to be “augmented both by numbers and by use in the right place.”

The past three years has seen an indiscriminate implementation of this technology, with the increased use of aerial attacks. On 19 April 2021, the villages of Botalanka and Palagudem experienced the first wave of aerial attacks, with villagers claiming at least 12 bombs were dropped on houses in the region. Almost exactly a year later, on the intervening night of 14 and 15 April 2022, locals accused security forces of another wave of drone bombardments that struck the villages of Bottethong, Mettaguda, Duled, Sakler, and Pottemangi, in Chhattisgarh’s Bijapur and Sukma districts. In January 2023, a third wave of aerial attacks took place, targeting Mettaguda and Bottethong again, as well as Errapalli village in Bijapur. Just two months later, the Bastar region witnessed its fourth drone bombing, in Bijapur’s Bhattiguda village. Each time, despite eyewitness accounts and villagers displaying shells of the bombs fired upon them, security forces denied the attacks.

The latest such attack took place earlier this year, on the night of 7 April, as police, paramilitary, and military forces converged on the villages and forests of Palaguda, Ittaguda, Jilorgada, Gommaguda, and Kanchal, in the Bijapur and Sukma districts. The operation began at 11.45 pm and lasting roughly half an hour, unleashed a barrage of destruction. According to Moolvasi Bachao Morchha—or Platform to Save the Original Inhabitants, a local civil-society organisation—the security forces deployed rocket launchers and drone bombs during the attacks. With over 30 high-explosive bombs fired, the attack decimated swathes of forest land, obliterating trees, plants, and wildlife within a 100-200 square meter radius. Many villagers narrowly escaped death, fleeing for their lives amid an atmosphere thick with smoke, fear and terror.

The timing of these attacks, each April for three consecutive years, is particularly devastating because it coincides with the peak of the Mahua harvest season. Mahua flowers, a crucial source of income for the tribals, require protection from wild and domestic animals. To safeguard their livelihood, people sleep under Mahua trees, spending most of their time in the forests. The bombings have disrupted this important activity, stripping them of their ability to collect forest produce, destroying the forests and their livelihoods, and pushing their already precarious existence further to the edge.

Under Modi, the central government has also been able to push through laws that circumvent legal hurdles to the clearance of forest lands, such as the consent of local tribal communities. After a decade of pushback from the tribal ministry, which predated the Modi government, the forest ministry issued the Forest Conservation Rules of 2022, which transfer the responsibility from the central to state governments to recognise tribal rights to traditional forestlands. The rules enable the central government to authorise forest clearing without prior consultation with inhabitants, compelling state governments to obtain consent from tribal and other forest-dwelling communities. Moreover, the rules allow the central government to authorise any forest clearance before the state government obtains the consent of the forest dwellers, effectively subverting the protections granted to them under the Forest Rights Act of 2006.

The Mines and Minerals Act of 2023, in conjunction with the union budgets for 2023-2024 and 2024-2025, serve as a revealing apparatus of biopolitical control. These legislative and fiscal measures demonstrate that the allocation of taxes to coal and mining by Indian states is not geared towards national development but is rather appropriated by a select oligarchy of financial capitalists. This appropriation not only encumbers the populace with oppressive debts but also exacerbates their economic and ecological vulnerability. Herein, the state’s fiscal policies become instruments for the perpetuation of systemic inequalities.

The enclosure of Bastar happens not only through laws and bills passed in the parliament, but also through discourse production in mainstream fiction that collude to exacerbate vulnerabilities that can be exploited. It is no surprise, then, and hardly coincidental, that the propaganda film “Bastar: The Naxal Story” was released in the midst of an election cycle and heightened security operations.

This film presents a violent distortion of the Salwa Judum militia and the Supreme Court’s declaration of its unconstitutionality. Its impact, however, is far more sinister. The film obfuscates the historical narratives of civil wars and indigenous resistance against the encroachments of mining corporations and developmental projects, through a warping of identities.

The film opens with a potent image: a Brahmin man, isolated in the deep forests, succumbs to the violence of a Maoist insurgent. This scene not only amplifies the portrayal of violence against settler Brahmins in Bastar, but does so by stripping any semblance of agency from the Adivasis, who are the actual guardians of the land. The film proceeds to dehumanise the Adivasis, reducing them to mere instruments of a “revolution.” A particularly telling scene depicts a female guerrilla fighter in an act of gluttony, starkly contrasted with the portrayal of the Brahmin mother or the sorrowful, modest mothers who nourish their children. It is a striking example of how cinema can manipulate empathy and moral alignment. The film not only provides an escape but actively reshapes viewers’ understanding of their place in the socio-economic hierarchy, masking colonialism and systemic issues with the allure of nationalist pride and progress, manufacturing acquiescence to the disappearance of people and lands.

The repression in Chhattisgarh reflects a broader pattern of violence and criminalization of indigenous and Dalit communities across India, particularly those advocating for their land rights and environmental protection. Villagers protest roads and development because these projects are wreaking havoc on their crops. In Aamdai Ghati, mining companies wash iron and coal, causing significant agricultural destruction. People of Dongar are particularly affected, as their crops are ruined by these activities. Contaminated water sources lead to livestock deaths, and drilling operations by corporations cause widespread respiratory issues among villagers. The hinterlands’ people now understand that roads do not mean progress for them but instead for the oligarchs and politicians.

The targeting of peaceful indigenous movements such as the Morohnar Jan Andolan and Orcha Jan Andolan, which resist mining projects and demand the implementation of protective laws, aims to silence their human rights work through fabricated charges and severe state violence. This crisis underscores the ongoing struggle of India’s Adivasi communities against marginalization and rights violations.

The erasure of Adivasi lands through corporate mining and militarisation results in the displacement, marginalisation, and physical and cultural destruction of their communities. In Bastar, bodies are made to disappear, forests to be obliterated, minerals to be spooled for the oligarchs and politicians, sustaining the survival of the colonial logic of the state.

(Photo caption: A protest by Adivasi women with their tools in the Orcha block of Chhattisgarh’s Naraynpur district. In recent months, the Bastar region has witnessed numerous protests against road construction, mining and civilian killings. PHOTO BY BHUMIKA SARASWATI.)

SUPPORT US

We like bringing the stories that don’t get told to you. For that, we need your support. However small, we would appreciate it.

Related Posts

The common silences and refrains that follow punitive demolitions