The disappearance of malnutrition under Smriti Irani: A lesson in narrative control

In a recent interview with Brut, Smriti Irani, the minister for women and child development, demonstrated with aggressive confidence, the skill of media spin. While the majority of the Indian media landscape champions the causes of the Narendra Modi government without being asked to, Irani showed how journalists who ask legitimate questions can be silenced, ridiculed, and dismissed, in order to successfully control the narrative. Undoubtedly, political manoeuvring is neither new nor unique to Modi’s cabinet, and journalists need to be informed and prepared while interviewing a minister. What is new, however, is the current regime’s effective control of the mass media, enabling a disappearance of the mind insofar as destroying any public space for a narrative that contradicts the government’s position on any subject. In the case of Irani and the Brut interview, the subject was malnutrition in India.

In the first ten minutes, during which Irani repeatedly interrupts and condescends Mehak Kasbekar, who conducted the interview, the Brut editor-in-chief manages to squeeze in one question: how did we get here? “Here” refers to the alarming state of malnutrition in India, and Kasbekar refers to two statistics to contextualise her question. First, she cites a recent peer-reviewed study by JAMA Network Open, a monthly medical journal published by the American Medical Association, which found a prevalence of 19.3 percent, around 67 lakh, “zero-food children” in India. The startling number and phrase refer to a terminology coined by the researchers to identify children aged between 6-23 months who did not have any food except breastmilk in the preceding 24 hours. Second, Kaskbekar cites Irani’s submission to the Rajya Sabha from March 2023, which stated that India had 14 lakh severely malnourished and 43 lakh malnourished children. Irani did not answer the question.

Instead, the union minister for child development took great umbrage at the two statistics cited by Kasbekar. “This is a fallacy,” Irani said, dismissing the JAMA study. She proceeded to challenge the credentials of one of the researchers, SV Subramanian, who is a professor of population health and geography at Harvard University. Irani accused him of taking money from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation without stating the purpose of his research, noting that “this gentleman particularly comes from a flawed and prejudiced position.” In response to her own Rajya Sabha submission, Irani emphasised that the metric for evaluation had been updated to the World Health Organization’s standards under the Modi regime, prior to which the number of severely malnourished children reported in India stood at 80 lakh.

Irani’s skill in media manipulation lay as much in her vehement dismissal of uncomfortable narratives, as it did in the lauding of her own efforts, never failing to mention that they were orchestrated under the auspices of Prime Minister Modi’s leadership. She repeatedly highlighted the ministry’s flagship initiative, the Poshan Tracker, which is the largest phone-based nutrition surveillance system in the world, tracking 75 million children in the country under the age of six, and the supplementary nutrition delivered to them. She noted that under Modi, India had seen a “tectonic shift” with Anganwadi workers now trained to measure nutritional information as per WHO standards for child growth, and empowered them with digital devices to track this information. The minister then identified malnutrition as a generational problem, and noted that Modi had launched the Pradhan Mantri Matru Vandana Yojana, a maternity benefit scheme providing direct cash transfers or financial subsidies to pregnant women, to address undernourishment among women. Irani hailed the disbursement of Rs 14,000 crore to three crore women under the scheme.

What Irani does not address, however, is why despite all these measures, does India still suffer such an alarming prevalence of malnutrition? To address this would be to acknowledge it, which the minister evaded successfully. To address it, it is necessary to understand it, and engage with experts, activists and professionals who have studied it, rather than suppress and dismiss uncomfortable facts.

Understanding child malnutrition in India

Since 2006, the universal standard for measuring child nutrition has been the WHO’s growth standards, based on anthropometric measures of undernutrition, determined by their height and weight. The WHO’s child growth standards are based on a Multi Growth Reference Study undertaken between 1997 and 2003, which collected growth data from around 8,500 children across six countries—Brazil, Ghana, India, Norway, Oman and the United States. The study sought to shift the global health order’s understanding of child growth, by not measuring how children do grow, but instead measuring how they should grow. It documented the growth patterns of children in order to develop a standard based on “healthy children living under conditions likely to favour achievement of their full genetic growth potential.” The study found that across the regions, children grew in similar anthropometric patterns when given proper nutrition.

On this basis, the WHO defined three indices for undernutrition based on the degree of deviation from the median child growth standards, as determined by their ideal height and weight for a particular age. These indices measure children who are underweight (low weight for age), stunting (low height for age), and wasting (low weight for height). These standards further guide our understanding of malnutrition by classifying it under two categories—moderate acute malnutrition (MAM), marked by between two and three standard deviations from the WHO’s weight-for-height median, and severe acute malnutrition (SAM), marked by over three standard deviations. (The medians and the deviations for all indices can be seen at the WHO’s website.)

Since its introduction, India has adopted these child growth standards and indices for measuring child nutrition, in its large-scale surveys, such as the National Family Health Survey (NFHS), in its Integrated Child Development Scheme, and now in the Poshan Tracker. The WHO child growth standards have recently come under question for its applicability, with research demonstrating that the underweight and wasting metrics need to account for other geographical and socio-economic factors, and the NITI Aayog has begun the process for a developing a new India-specific growth standard. But Irani did not mention any of this, and hailed the WHO’s standards implemented under the Poshan Tracker, claiming that child nutrition measurement under the previous Congress regime were based on “sub-Saharan African results which were compared with India.” In fact, the numbers she cited were based on the same WHO standards that she claimed to introduce to India. More importantly, even the measurements with Irani at the helm of the ministry paint a bleak picture of the state of child nutrition in India.

The NFHS-3 (2005-06) found that 6.4% of the children—around 8.1 million, according to a 2013 health ministry report—were severely wasted, or suffering from SAM. The NFHS-4 (2015-16) reported that this figure had risen to 7.5%, and NFHS-5 (2019-21) saw this rise further to 7.7%. According to the latest Poshan Tracker data, 6% of the children measured in March 2024 suffered from acute malnourishment, purportedly including both SAM and MAM cases. However, given that the MAM prevalence in India according to the NFHS-4 and NFHS-5 were 21% and 19.3%, respectively, the sudden 13-percent drop raises questions about the system.

NFHS-5 unveiled other troubling trends too: child nutrition indicators stagnated or worsened in ten major states from 2015-16 to 2019-20, with increases in underweight and stunted children in several states. The rates of underweight and stunting across India stood at 32.1% and 35.5% respectively, suggesting that over one-third of children under five are likely underweight and stunted. The survey also revealed a rise in anaemia rates among children under five, increasing from 58.69% in 2015-16 to 67.1% in 2019-21.

Zero-food children and other measures of child nutrition

Despite such strong evidence of the malnutrition crisis in India, Irani dismissed the JAMA study as a fallacy, adding, “If you tell me, 60 lakh children in country had no food, you’re telling my Brut would be sitting quiet and not reporting? Doesn’t make sense.” But the minister had misstated—whether intentionally or unwittingly—the study’s findings. The JAMA study conducted a study of 276,379 children aged 6–23 months, from 92 low- and middle-income countries, to identify how many children had not been fed any animal milk, formula, or solid or semisolid foods during the 24 hours before the survey, as reported by the mother or caretaker.

The study is based on the WHO’s recommended nutritional practices for feeding infants and young children, which states that children should be exclusively breastfed for the first six months of their lives, following which complementary solid and semi-solid foods should be introduced for energy and nutrient needs. The children who did not receive any such food, not including breastmilk, were termed as “zero-food children.” Published in February this year, the results showed that India had the greatest prevalence of such zero-food children, and the third-highest in total numbers. Pertinently, two of the researchers behind the study—including Subramanian—had conducted a more focused study on India the previous year, relying on data from all five NFHS from 1993 to 2021, to measure the prevalence of zero-food children across the country.

The study was published in Lancet in April 2023. It showed that the all-India prevalence of zero-food children decreased from 20% in 1993, to 17.8% in 2021 with an estimated over 59 lakh zero-food children. (The JAMA study conducted the India surveys between 2019-21 and found the prevalence to be 19.3% and total number to be 67 lakh.) The Lancet study also found significant inter-state variations, with Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Maharashtra, Rajasthan and Madhya Pradesh accounting for nearly two-thirds of the total number. Both studies recommend targeted interventions with greater precision to ensure better facilitation of child nutrition.

The NFHS-5 itself points to the inadequate diet of the vast majority of children. Based on the WHO’s optimum feeding practices, the survey notes that only 11.3% of children aged 6-23 months were receiving an adequate diet. It is not hard to believe, then, that India’s zero-food children prevalence and numbers would be as high as reported. Yet, the study, its lead researcher, and the Brut editor-in-chief received harsh rebukes from the union minister for women and child development. Perhaps for the alarmist terminology, but the crisis of child malnutrition in India is a fact, whatever name it goes by.

Nutrition is multidimensional

It is well accepted that addressing malnutrition requires a multifaceted approach, that includes improving access to water and sanitation, education, and healthcare systems, among others. According to a report published by Public Health Resource Network, a group of doctors and scientists working in public health, malnutrition among Indian children under five is a pressing public health issue, accounting for a staggering 68.2% of all under-five deaths in the country.

Early childhood nutritional deficiencies not only impact physical health but also hinder social and mental development, perpetuating a cycle of malnutrition and increasing child mortality and morbidity rates. Despite multiple initiatives, efforts to combat child malnutrition in India have been uneven, with notable progress in certain states contrasted by stagnation in others. While existing programs prioritise food and diet, crucial factors such as disease, hygiene, sanitation, poverty, employment, and socio-economic and political dynamics often receive inadequate attention. In Unshackling India, Ajay Chhibber and Salman Anees Soz contend that out of India’s 1.3 billion population, 163 million lack access to clean water, while 732 million lack adequate toilet facilities. Additionally, over 60,000 children under five succumb to diarrhoea annually due to contaminated water and inadequate sanitation. They underscore that as long as sanitation hurdles persist, akin to malnutrition, achieving positive health outcomes will remain elusive.

In The Making of a Catastrophe, Jayati Ghosh writes about how COVID-19 was not just a health disaster in India but also caused economic devastation. She notes that with the deprivation of livelihoods for millions during the pandemic, in a country like India where over 90% of workers operate informally, the loss of even a week’s income can plunge individuals into starvation. Despite burgeoning food stocks, the government released only paltry amounts due to large-scale exclusions, exacerbating hunger amid escalating unemployment auguring grave consequences for maternal, infant, and child nutrition. With low public spending on the health sector, the majority of the population must contend with severely inadequate and overcrowded public facilities, relying on often inadequately trained local practitioners. Moreover, many cannot even afford the essential medications necessary for treatment.

As highlighted by the Right to Food campaign that broke down the 2024-25 budget, there has been a 40% decline in the budget allocated for ICDS and mid-day meals. The budget allocated for ICDS for 2024-25 has been Rs 17,808 crore as compared to Rs 18,691 crore in 2014-15. Keeping the inflation rates (5% annually), the decline is staggering. Declines in budgets can neither plug leakages or increase efficiency of any delivery, especially in a country like India where in the light of stagnation of growth, what is required from the side of the government is increase in budget allocation.

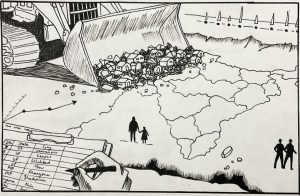

With subsequent cuts in health funding, including detrimental slashes to Integrated Child Development Services (ICDS), millions find themselves disenfranchised from the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA), while unemployment proliferates unabated, eroding purchasing power—an aspect inadequately reflected in consumption data disseminated by the NITI Aayog or the Poshan Tracker. In a vacuum void of independent media or market influences, co-opted by favourable narratives, the state constructs insulated silos of illusion—such as the disappearance of malnutrition in India.

Related Posts

The disappearance of malnutrition under Smriti Irani: A lesson in narrative control

In a recent interview with Brut, Smriti Irani, the minister for women and child development, demonstrated with aggressive confidence, the skill of media spin. While the majority of the Indian media landscape champions the causes of the Narendra Modi government without being asked to, Irani showed how journalists who ask legitimate questions can be silenced, ridiculed, and dismissed, in order to successfully control the narrative. Undoubtedly, political manoeuvring is neither new nor unique to Modi’s cabinet, and journalists need to be informed and prepared while interviewing a minister. What is new, however, is the current regime’s effective control of the mass media, enabling a disappearance of the mind insofar as destroying any public space for a narrative that contradicts the government’s position on any subject. In the case of Irani and the Brut interview, the subject was malnutrition in India.

In the first ten minutes, during which Irani repeatedly interrupts and condescends Mehak Kasbekar, who conducted the interview, the Brut editor-in-chief manages to squeeze in one question: how did we get here? “Here” refers to the alarming state of malnutrition in India, and Kasbekar refers to two statistics to contextualise her question. First, she cites a recent peer-reviewed study by JAMA Network Open, a monthly medical journal published by the American Medical Association, which found a prevalence of 19.3 percent, around 67 lakh, “zero-food children” in India. The startling number and phrase refer to a terminology coined by the researchers to identify children aged between 6-23 months who did not have any food except breastmilk in the preceding 24 hours. Second, Kaskbekar cites Irani’s submission to the Rajya Sabha from March 2023, which stated that India had 14 lakh severely malnourished and 43 lakh malnourished children. Irani did not answer the question.

Instead, the union minister for child development took great umbrage at the two statistics cited by Kasbekar. “This is a fallacy,” Irani said, dismissing the JAMA study. She proceeded to challenge the credentials of one of the researchers, SV Subramanian, who is a professor of population health and geography at Harvard University. Irani accused him of taking money from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation without stating the purpose of his research, noting that “this gentleman particularly comes from a flawed and prejudiced position.” In response to her own Rajya Sabha submission, Irani emphasised that the metric for evaluation had been updated to the World Health Organization’s standards under the Modi regime, prior to which the number of severely malnourished children reported in India stood at 80 lakh.

Irani’s skill in media manipulation lay as much in her vehement dismissal of uncomfortable narratives, as it did in the lauding of her own efforts, never failing to mention that they were orchestrated under the auspices of Prime Minister Modi’s leadership. She repeatedly highlighted the ministry’s flagship initiative, the Poshan Tracker, which is the largest phone-based nutrition surveillance system in the world, tracking 75 million children in the country under the age of six, and the supplementary nutrition delivered to them. She noted that under Modi, India had seen a “tectonic shift” with Anganwadi workers now trained to measure nutritional information as per WHO standards for child growth, and empowered them with digital devices to track this information. The minister then identified malnutrition as a generational problem, and noted that Modi had launched the Pradhan Mantri Matru Vandana Yojana, a maternity benefit scheme providing direct cash transfers or financial subsidies to pregnant women, to address undernourishment among women. Irani hailed the disbursement of Rs 14,000 crore to three crore women under the scheme.

What Irani does not address, however, is why despite all these measures, does India still suffer such an alarming prevalence of malnutrition? To address this would be to acknowledge it, which the minister evaded successfully. To address it, it is necessary to understand it, and engage with experts, activists and professionals who have studied it, rather than suppress and dismiss uncomfortable facts.

Understanding child malnutrition in India

Since 2006, the universal standard for measuring child nutrition has been the WHO’s growth standards, based on anthropometric measures of undernutrition, determined by their height and weight. The WHO’s child growth standards are based on a Multi Growth Reference Study undertaken between 1997 and 2003, which collected growth data from around 8,500 children across six countries—Brazil, Ghana, India, Norway, Oman and the United States. The study sought to shift the global health order’s understanding of child growth, by not measuring how children do grow, but instead measuring how they should grow. It documented the growth patterns of children in order to develop a standard based on “healthy children living under conditions likely to favour achievement of their full genetic growth potential.” The study found that across the regions, children grew in similar anthropometric patterns when given proper nutrition.

On this basis, the WHO defined three indices for undernutrition based on the degree of deviation from the median child growth standards, as determined by their ideal height and weight for a particular age. These indices measure children who are underweight (low weight for age), stunting (low height for age), and wasting (low weight for height). These standards further guide our understanding of malnutrition by classifying it under two categories—moderate acute malnutrition (MAM), marked by between two and three standard deviations from the WHO’s weight-for-height median, and severe acute malnutrition (SAM), marked by over three standard deviations. (The medians and the deviations for all indices can be seen at the WHO’s website.)

Since its introduction, India has adopted these child growth standards and indices for measuring child nutrition, in its large-scale surveys, such as the National Family Health Survey (NFHS), in its Integrated Child Development Scheme, and now in the Poshan Tracker. The WHO child growth standards have recently come under question for its applicability, with research demonstrating that the underweight and wasting metrics need to account for other geographical and socio-economic factors, and the NITI Aayog has begun the process for a developing a new India-specific growth standard. But Irani did not mention any of this, and hailed the WHO’s standards implemented under the Poshan Tracker, claiming that child nutrition measurement under the previous Congress regime were based on “sub-Saharan African results which were compared with India.” In fact, the numbers she cited were based on the same WHO standards that she claimed to introduce to India. More importantly, even the measurements with Irani at the helm of the ministry paint a bleak picture of the state of child nutrition in India.

The NFHS-3 (2005-06) found that 6.4% of the children—around 8.1 million, according to a 2013 health ministry report—were severely wasted, or suffering from SAM. The NFHS-4 (2015-16) reported that this figure had risen to 7.5%, and NFHS-5 (2019-21) saw this rise further to 7.7%. According to the latest Poshan Tracker data, 6% of the children measured in March 2024 suffered from acute malnourishment, purportedly including both SAM and MAM cases. However, given that the MAM prevalence in India according to the NFHS-4 and NFHS-5 were 21% and 19.3%, respectively, the sudden 13-percent drop raises questions about the system.

NFHS-5 unveiled other troubling trends too: child nutrition indicators stagnated or worsened in ten major states from 2015-16 to 2019-20, with increases in underweight and stunted children in several states. The rates of underweight and stunting across India stood at 32.1% and 35.5% respectively, suggesting that over one-third of children under five are likely underweight and stunted. The survey also revealed a rise in anaemia rates among children under five, increasing from 58.69% in 2015-16 to 67.1% in 2019-21.

Zero-food children and other measures of child nutrition

Despite such strong evidence of the malnutrition crisis in India, Irani dismissed the JAMA study as a fallacy, adding, “If you tell me, 60 lakh children in country had no food, you’re telling my Brut would be sitting quiet and not reporting? Doesn’t make sense.” But the minister had misstated—whether intentionally or unwittingly—the study’s findings. The JAMA study conducted a study of 276,379 children aged 6–23 months, from 92 low- and middle-income countries, to identify how many children had not been fed any animal milk, formula, or solid or semisolid foods during the 24 hours before the survey, as reported by the mother or caretaker.

The study is based on the WHO’s recommended nutritional practices for feeding infants and young children, which states that children should be exclusively breastfed for the first six months of their lives, following which complementary solid and semi-solid foods should be introduced for energy and nutrient needs. The children who did not receive any such food, not including breastmilk, were termed as “zero-food children.” Published in February this year, the results showed that India had the greatest prevalence of such zero-food children, and the third-highest in total numbers. Pertinently, two of the researchers behind the study—including Subramanian—had conducted a more focused study on India the previous year, relying on data from all five NFHS from 1993 to 2021, to measure the prevalence of zero-food children across the country.

The study was published in Lancet in April 2023. It showed that the all-India prevalence of zero-food children decreased from 20% in 1993, to 17.8% in 2021 with an estimated over 59 lakh zero-food children. (The JAMA study conducted the India surveys between 2019-21 and found the prevalence to be 19.3% and total number to be 67 lakh.) The Lancet study also found significant inter-state variations, with Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Maharashtra, Rajasthan and Madhya Pradesh accounting for nearly two-thirds of the total number. Both studies recommend targeted interventions with greater precision to ensure better facilitation of child nutrition.

The NFHS-5 itself points to the inadequate diet of the vast majority of children. Based on the WHO’s optimum feeding practices, the survey notes that only 11.3% of children aged 6-23 months were receiving an adequate diet. It is not hard to believe, then, that India’s zero-food children prevalence and numbers would be as high as reported. Yet, the study, its lead researcher, and the Brut editor-in-chief received harsh rebukes from the union minister for women and child development. Perhaps for the alarmist terminology, but the crisis of child malnutrition in India is a fact, whatever name it goes by.

Nutrition is multidimensional

It is well accepted that addressing malnutrition requires a multifaceted approach, that includes improving access to water and sanitation, education, and healthcare systems, among others. According to a report published by Public Health Resource Network, a group of doctors and scientists working in public health, malnutrition among Indian children under five is a pressing public health issue, accounting for a staggering 68.2% of all under-five deaths in the country.

Early childhood nutritional deficiencies not only impact physical health but also hinder social and mental development, perpetuating a cycle of malnutrition and increasing child mortality and morbidity rates. Despite multiple initiatives, efforts to combat child malnutrition in India have been uneven, with notable progress in certain states contrasted by stagnation in others. While existing programs prioritise food and diet, crucial factors such as disease, hygiene, sanitation, poverty, employment, and socio-economic and political dynamics often receive inadequate attention. In Unshackling India, Ajay Chhibber and Salman Anees Soz contend that out of India’s 1.3 billion population, 163 million lack access to clean water, while 732 million lack adequate toilet facilities. Additionally, over 60,000 children under five succumb to diarrhoea annually due to contaminated water and inadequate sanitation. They underscore that as long as sanitation hurdles persist, akin to malnutrition, achieving positive health outcomes will remain elusive.

In The Making of a Catastrophe, Jayati Ghosh writes about how COVID-19 was not just a health disaster in India but also caused economic devastation. She notes that with the deprivation of livelihoods for millions during the pandemic, in a country like India where over 90% of workers operate informally, the loss of even a week’s income can plunge individuals into starvation. Despite burgeoning food stocks, the government released only paltry amounts due to large-scale exclusions, exacerbating hunger amid escalating unemployment auguring grave consequences for maternal, infant, and child nutrition. With low public spending on the health sector, the majority of the population must contend with severely inadequate and overcrowded public facilities, relying on often inadequately trained local practitioners. Moreover, many cannot even afford the essential medications necessary for treatment.

As highlighted by the Right to Food campaign that broke down the 2024-25 budget, there has been a 40% decline in the budget allocated for ICDS and mid-day meals. The budget allocated for ICDS for 2024-25 has been Rs 17,808 crore as compared to Rs 18,691 crore in 2014-15. Keeping the inflation rates (5% annually), the decline is staggering. Declines in budgets can neither plug leakages or increase efficiency of any delivery, especially in a country like India where in the light of stagnation of growth, what is required from the side of the government is increase in budget allocation.

With subsequent cuts in health funding, including detrimental slashes to Integrated Child Development Services (ICDS), millions find themselves disenfranchised from the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA), while unemployment proliferates unabated, eroding purchasing power—an aspect inadequately reflected in consumption data disseminated by the NITI Aayog or the Poshan Tracker. In a vacuum void of independent media or market influences, co-opted by favourable narratives, the state constructs insulated silos of illusion—such as the disappearance of malnutrition in India.

SUPPORT US

We like bringing the stories that don’t get told to you. For that, we need your support. However small, we would appreciate it.