Three days after proclaiming that he would “not do Hindu-Muslim,” Narendra Modi returned to his divisive, inflammatory rhetoric during a public meeting at Barabanki on 17 May. The prime minister warned voters that a Congress and Samajwadi Party alliance would bulldoze the Ram Temple, and suggested that they “take tuition” from the Uttar Pradesh chief minister on “where to run bulldozers.” While the Congress flagged Modi’s comments to the Election Commission of India, it did so for “saying such things about the temple of god”—not for the unambiguous dog whistles about destroying Muslim homes. It is imperative to ask the opposition why it has shied away from addressing “bulldozer politics” in its campaign.

Our research on demolitions in Uttar Pradesh, as well as previous studies and reports on the topic, have all shown that the Adityanath regime’s flagship policy of punitive destructions primarily targets the Muslim community. The opposition’s failure to take it up as a campaign issue reflects the normalisation of the phenomenon, and the decreasing attention it receives from the media and by politicians. Though there have been no recent hyper-publicised incidents of punitive demolitions, families that suffered the ordeal remember everything like it was yesterday.

In today’s news cycle it is difficult to fixate on a singular issue, with a multitude of threats and violence being unleashed on marginalised populations. As a result, the demolitions become forgotten—not just by the media, but in public memory as well, even by residents of the cities that witnessed the targeted demolitions. With the Demolitions project, we choose to fixate on this issue, even when the news cycle has moved on, and document all instances of punitive, extrajudicial demolitions.

We started our research looking at the demolitions of properties owned by Muslims in the cities of Kanpur, Saharanpur, and Allahabad (now Prayagraj) in response to protests against remarks by Nupur Sharma, a former national spokesperson of BJP. All three districts witnessed demolitions in the aftermath of the protests against Sharma’s remarks, which had reportedly turned violent. According to the notices received by affected families, the district development authorities were functioning independently, and the properties were either illegal or encroachments, allegedly unrelated to the protests but coincidentally timed in response to them.

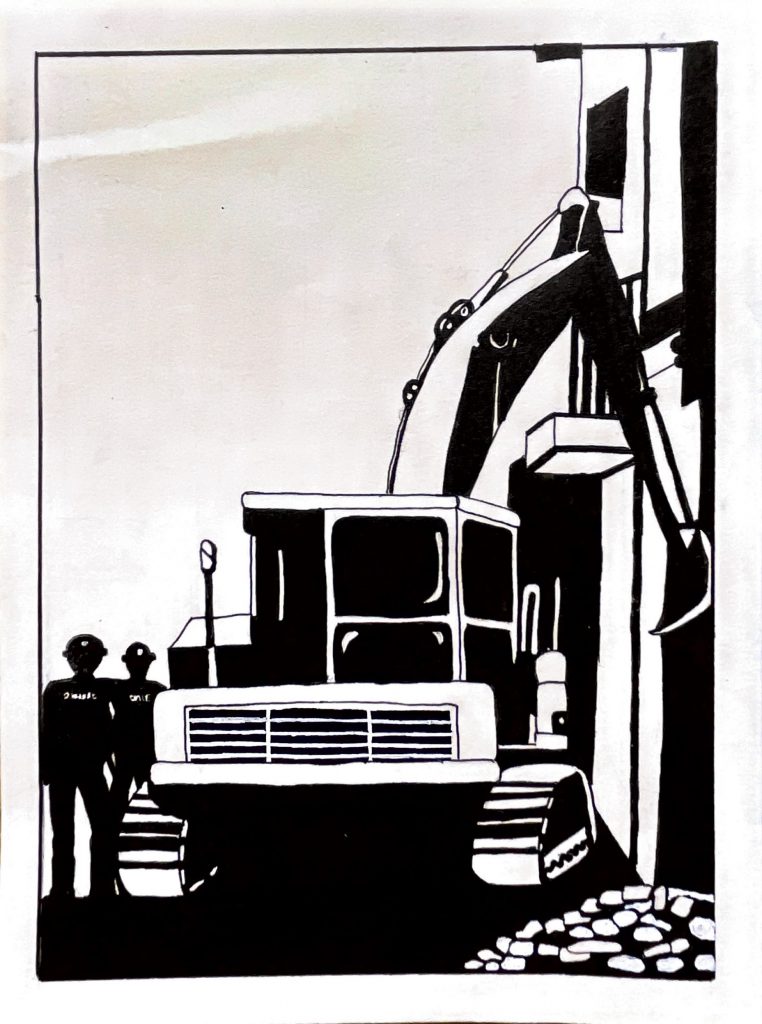

The authorities have made the same claims in court, but district and government officials have admitted, on camera, that the demolitions were in fact punitive action against “dangai”—rioters. Adityanath, too, posted on X on 11 June 2022, “Apradhiyon/mafiyayon ke virudh bulldozer ki karyavai satata jari rahegi”—Bulldozer action against criminals/mafia will continue. After this statement, three properties were completely demolished and two partially demolished in Uttar Pradesh, including two demolitions in Kanpur on the same day. The Kanpur Development Authority announced in a statement that it had demolished two properties, owned by Mohammed Ishtiyaq and Riyaz Ahmed.

Ishtiyaq’s property was an under-construction shopping complex in Swaroop Nagar, located at least three kilometres from the sites of violence that reportedly broke out in the city on 3 June 2022. The Kanpur Development Authority demolished it using three bulldozers, for allegedly encroaching on public land. While the KDA maintained that it was a “routine” demolition and part of its “campaign against land mafia,” local police officials identified Ishtiyaq as a close relative of Zafar Hayat Hashmi, one of the main accused in the Kanpur violence. But Ishtiyaq’s son, Ifteqar Ahmad, told the Indian Express that his father died in 2018, and that he himself would not be able to recognise Hashmi “if you make him stand in front of me.”

Riyaz Ahmed’s property was an under-construction petrol pump, and its demolition was shrouded in similar contradictions, with the KDA citing routine procedure, and the police alleging links to Hashmi. Meanwhile, after being released on bail, Hashmi denied knowing either of the owners.

In the wake of these demolitions, the sentiments in the city were similar—the local Muslim population said it received the message behind the rumbling of bulldozers through the city streets. One local resident, who asked to remain anonymous, remarked, “There is law, there is court, you [district authorities] cannot demolish structures on your whim, follow the procedure and if it comes to it demolish everything. The clash was from both sides, how come no Hindu property was touched? Are all illegal properties only of Muslims? This kind of action should not be taken out, let law take its course and on mere suspicion you are ruining the hard work of someone.”

The Adityanath government is celebrated for its bulldozer action despite—or perhaps because of—his disregard for due process and the necessary court orders and permits needed for a demolition. His second term as chief minister has seen the state popularise its policy of “bulldozer justice,” and earned him the moniker of “Bulldozer Baba.” We leave this month’s newsletter with the question: is “bulldozer justice” simply the state’s version of mob justice?