The House That Wasn’t: Tauheed Fatima and the loss of a home

Tauheed Fatima does not remember how she got ready that morning. She does not remember the details of how she rushed to the site of her new home—one she was meant to move into in a few days, and where her father had poured his life’s earnings with unwavering love for his youngest daughter. She does not remember what words she spoke or what cries left her mouth. What she does remember, what she cannot forget, is the sound of bulldozers, the voices of men shouting, and the helplessness that swallowed her whole.

She had not lived in that house yet. But it had already begun to live within her.

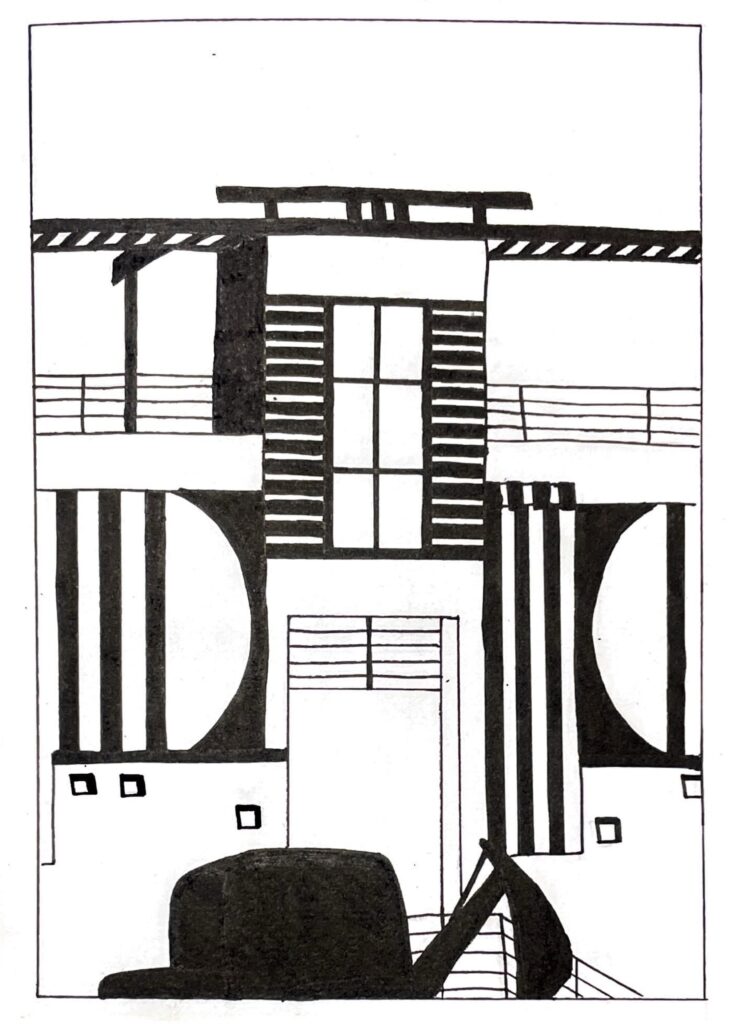

She had imagined the placement of every mat. When she traveled to Delhi, she wandered through markets, carefully picking out home décor, lamps, and curtains; looking for the right lighting, the perfect shades of warmth. She had wanted to move in with a sense of celebration, marking the transition with a Quran Khani—a practice among Muslims to collectively read the Quran, often followed by a meal marking the start of something new—on the day she would move into her new house, on 7 March 2023. Instead, four days before that, on 3 March, bulldozers reached her newly constructed home in Bamraulli, Prayagraj, and reduced it to rubble.

“Koi time nahi diya ki ghar se kuch nikale,” Fatima said. (We weren’t given any time to take anything out of the house.) “Everything was brand new. They didn’t even issue a notice—after repeatedly asking, they showed us just one notice.” The notice was backdated to 10 January 2023, and addressed to Mohammad Mashooquddin, Tauheed’s father-in-law. It stated that their house plan was not sanctioned, because of which the structure was illegal and going to be demolished. Tauheed or Mashooquddin, for that matter, were never served the said notice. Their lawyer filed an RTI with the Prayagraj Development Authority to get a copy of the notice but has not received a response yet.

Fatima tears up when asked about that day. Words do not come to her. Her father, Junaid Ahmed, too, is quiet. They do not speak of their grief in full sentences. They speak in the language of documents and legal petitions, of notices and submissions. It is as if the weight of what they lost is too much to bear in words, too much to articulate in the plain language of sorrow.

Fatima is 25 years old, a teacher of elementary Urdu and Arabic at a madarssa, and a mother of two young sons, one five and the other two and a half. She had no connection to any crime, no shadow of illegality hanging over her. She only had the dreams of a woman seeking a home of her own, the steadfast support of her parents who wanted to make that dream a reality, and the land gifted to her by Mashooquddin, the village pradhan, or leader, of Ahmadhpur.

The home that stood on that land, built with love and financial sacrifices, did not exist for long. Tauheed’s father and mother had taken out a personal loan to construct the house. They wanted to secure their daughter’s future, to see her and her children settled. The house was built on 2,500 square feet of land, a space filled with promise, a structure that had passed through every legal process required by the state.

When the construction had started in August 2022, they had received a notice from the Prayagraj Development Authority (PDA), asking for the building map. They submitted it without delay. A clarification was later requested by PDA. They complied and submitted that. When Fatima’s father attended the submission hearing, an officer assured him, “Jaiye, shaan se apna makaan banvaiye”—Go, build your home with pride. For nearly a year after that, they heard nothing. No objections, no orders to halt construction, no further requests. The house rose, brick by brick, under the watchful eyes of a father determined to see his daughter secure.

Then, in February 2023, Umesh Pal was murdered. Umesh was a key witness in a 2005 case concerning the murder of Raju Pal, a member of UP’s state assembly from the Bahujan Samaj Party. The gangster-politician Atiq Ahmed and his brother, Ashraf were accused of orchestrating both murders.

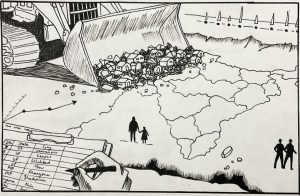

The Umesh Pal murder sent ripples through Uttar Pradesh’s political and law-enforcement circles. Accusations flew, and anyone remotely associated with Atiq came under suspicion. Mashooquddin was accused of funding Atiq—a claim his family vehemently denies. If anything, they say, their political circles never aligned; despite belonging to the same caste, they were more rivals than allies. But in the chief minister Ajay Singh Bisht’s Uttar Pradesh, where bulldozers have become instruments of extrajudicial punishment, the burden of proof never falls on the state. It falls on the accused. And it falls on Muslims not even accused of any crime, except practicing their faith.

March 3, 2023, was a Friday. As men left the mosque after prayers, the news spread. Three bulldozers had reached Fatima’s house.

Her father and brother rushed to the site. They pleaded, argued, demanded an explanation. When they asked for an official notice, a document addressed not to Fatima, the legal owner of the home, but to her father-in-law was shown. A notice that was backdated, never actually served, and offered her no opportunity to challenge its claims.

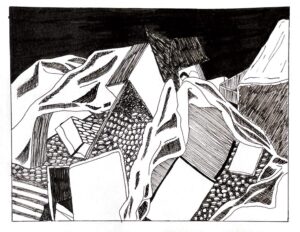

The demolition began anyway.

“Maine apne ghar ke sapne dekhe the, har kone ko sajane ka socha tha”— I had dreamed of moving into my own home, of decorating every corner, Fatima said. “Maine apni pasand se lights, parde, sab kuch chuna tha. Lekin uss ghar mein qadam rakhne se pehle hi unhone usey todh diya.” (I had picked out the lights, the curtains, everything. But before I could step into it, they demolished it.)

Fatima arrived soon after, but her memory of the day remains a haze of panic and helplessness. She only knows that by the time the dust settled, there was no house. No space of her own. No home to return to.

Her father does not dwell on the emotions of that day. Instead, Junaid fights it legally. He has documented everything. Every notice, every submission, every receipt. His meticulous file is a silent testament to the weight of his loss and his refusal to let it go unanswered. When asked about the case, he turns its pages quickly, offering dates, details, evidence. He knows the demolition was unjust and illegal. The process was flawed. The house should have never been destroyed.

“Do saal ho gaye hain, hum ab tak insaaf ka intezar kar rahe hain”— It has been two years, and we are still waiting for justice, Junaid said. “Karz bhi hai, kar rahe hain sab kuch ka saamna.” (The debt is also there, we are facing everything.)

He continued, “Ek baap kya chahta hai? Sirf yeh ki uski beti ke paas apna ek ghar ho, jismein woh sukoon se reh sake. Maine iske liye mehnat ki, lekin sarkar ne ek hi din mein chheen liya.” (What does a father want? For his daughter to have a home of her own, a place where she can live comfortably. I worked hard for that, but the state took it away in one day.)

Through it all, Fatima does not let despair consume her. She battles depression, but she holds onto faith. “Allah ke qadr par yakeen karna chahiye,” she said–one must have faith in Allah’s decree.)

At an age when most women are still building their futures, Fatima has already had hers torn down before her eyes. But she does not surrender. She continues to teach, to raise her children, to fight in the courts. She carries within her an unbreakable will, a belief that justice, even if delayed, will come.

The house she built may be gone. But the home she carries within her—the one made of resilience, love, and faith—remains unshaken.

Related Posts

Tauheed Fatima does not remember how she got ready that morning. She does not remember the details of how she rushed to the site of her new home—one she was meant to move into in a few days, and where her father had poured his life’s earnings with unwavering love for his youngest daughter. She does not remember what words she spoke or what cries left her mouth. What she does remember, what she cannot forget, is the sound of bulldozers, the voices of men shouting, and the helplessness that swallowed her whole.

She had not lived in that house yet. But it had already begun to live within her.

She had imagined the placement of every mat. When she traveled to Delhi, she wandered through markets, carefully picking out home décor, lamps, and curtains; looking for the right lighting, the perfect shades of warmth. She had wanted to move in with a sense of celebration, marking the transition with a Quran Khani—a practice among Muslims to collectively read the Quran, often followed by a meal marking the start of something new—on the day she would move into her new house, on 7 March 2023. Instead, four days before that, on 3 March, bulldozers reached her newly constructed home in Bamraulli, Prayagraj, and reduced it to rubble.

“Koi time nahi diya ki ghar se kuch nikale,” Fatima said. (We weren’t given any time to take anything out of the house.) “Everything was brand new. They didn’t even issue a notice—after repeatedly asking, they showed us just one notice.” The notice was backdated to 10 January 2023, and addressed to Mohammad Mashooquddin, Tauheed’s father-in-law. It stated that their house plan was not sanctioned, because of which the structure was illegal and going to be demolished. Tauheed or Mashooquddin, for that matter, were never served the said notice. Their lawyer filed an RTI with the Prayagraj Development Authority to get a copy of the notice but has not received a response yet.

Fatima tears up when asked about that day. Words do not come to her. Her father, Junaid Ahmed, too, is quiet. They do not speak of their grief in full sentences. They speak in the language of documents and legal petitions, of notices and submissions. It is as if the weight of what they lost is too much to bear in words, too much to articulate in the plain language of sorrow.

Fatima is 25 years old, a teacher of elementary Urdu and Arabic at a madarssa, and a mother of two young sons, one five and the other two and a half. She had no connection to any crime, no shadow of illegality hanging over her. She only had the dreams of a woman seeking a home of her own, the steadfast support of her parents who wanted to make that dream a reality, and the land gifted to her by Mashooquddin, the village pradhan, or leader, of Ahmadhpur.

The home that stood on that land, built with love and financial sacrifices, did not exist for long. Tauheed’s father and mother had taken out a personal loan to construct the house. They wanted to secure their daughter’s future, to see her and her children settled. The house was built on 2,500 square feet of land, a space filled with promise, a structure that had passed through every legal process required by the state.

When the construction had started in August 2022, they had received a notice from the Prayagraj Development Authority (PDA), asking for the building map. They submitted it without delay. A clarification was later requested by PDA. They complied and submitted that. When Fatima’s father attended the submission hearing, an officer assured him, “Jaiye, shaan se apna makaan banvaiye”—Go, build your home with pride. For nearly a year after that, they heard nothing. No objections, no orders to halt construction, no further requests. The house rose, brick by brick, under the watchful eyes of a father determined to see his daughter secure.

Then, in February 2023, Umesh Pal was murdered. Umesh was a key witness in a 2005 case concerning the murder of Raju Pal, a member of UP’s state assembly from the Bahujan Samaj Party. The gangster-politician Atiq Ahmed and his brother, Ashraf were accused of orchestrating both murders.

The Umesh Pal murder sent ripples through Uttar Pradesh’s political and law-enforcement circles. Accusations flew, and anyone remotely associated with Atiq came under suspicion. Mashooquddin was accused of funding Atiq—a claim his family vehemently denies. If anything, they say, their political circles never aligned; despite belonging to the same caste, they were more rivals than allies. But in the chief minister Ajay Singh Bisht’s Uttar Pradesh, where bulldozers have become instruments of extrajudicial punishment, the burden of proof never falls on the state. It falls on the accused. And it falls on Muslims not even accused of any crime, except practicing their faith.

March 3, 2023, was a Friday. As men left the mosque after prayers, the news spread. Three bulldozers had reached Fatima’s house.

Her father and brother rushed to the site. They pleaded, argued, demanded an explanation. When they asked for an official notice, a document addressed not to Fatima, the legal owner of the home, but to her father-in-law was shown. A notice that was backdated, never actually served, and offered her no opportunity to challenge its claims.

The demolition began anyway.

“Maine apne ghar ke sapne dekhe the, har kone ko sajane ka socha tha”— I had dreamed of moving into my own home, of decorating every corner, Fatima said. “Maine apni pasand se lights, parde, sab kuch chuna tha. Lekin uss ghar mein qadam rakhne se pehle hi unhone usey todh diya.” (I had picked out the lights, the curtains, everything. But before I could step into it, they demolished it.)

Fatima arrived soon after, but her memory of the day remains a haze of panic and helplessness. She only knows that by the time the dust settled, there was no house. No space of her own. No home to return to.

Her father does not dwell on the emotions of that day. Instead, Junaid fights it legally. He has documented everything. Every notice, every submission, every receipt. His meticulous file is a silent testament to the weight of his loss and his refusal to let it go unanswered. When asked about the case, he turns its pages quickly, offering dates, details, evidence. He knows the demolition was unjust and illegal. The process was flawed. The house should have never been destroyed.

“Do saal ho gaye hain, hum ab tak insaaf ka intezar kar rahe hain”— It has been two years, and we are still waiting for justice, Junaid said. “Karz bhi hai, kar rahe hain sab kuch ka saamna.” (The debt is also there, we are facing everything.)

He continued, “Ek baap kya chahta hai? Sirf yeh ki uski beti ke paas apna ek ghar ho, jismein woh sukoon se reh sake. Maine iske liye mehnat ki, lekin sarkar ne ek hi din mein chheen liya.” (What does a father want? For his daughter to have a home of her own, a place where she can live comfortably. I worked hard for that, but the state took it away in one day.)

Through it all, Fatima does not let despair consume her. She battles depression, but she holds onto faith. “Allah ke qadr par yakeen karna chahiye,” she said–one must have faith in Allah’s decree.)

At an age when most women are still building their futures, Fatima has already had hers torn down before her eyes. But she does not surrender. She continues to teach, to raise her children, to fight in the courts. She carries within her an unbreakable will, a belief that justice, even if delayed, will come.

The house she built may be gone. But the home she carries within her—the one made of resilience, love, and faith—remains unshaken.

SUPPORT US

We like bringing the stories that don’t get told to you. For that, we need your support. However small, we would appreciate it.