Architectural violence: State-sanctioned demolitions in Palestine and India

State-sanctioned demolitions are distinct and powerful tools of control and punishment in both Israel and India, targeting specific marginalised communities in these disparate geographies. While operating in vastly different historical and political contexts, both nations have weaponised demolition policies against the communities they see as the Other—Palestinians in Israeli occupied lands, and Muslims in India. These demolitions function as expressions of state control, revealing striking parallels in their justifications and implementations, while also underlining the differences in the respective practices in Palestine and India. By comparing these practices, what emerges is the understanding of how architectural violence becomes institutionalised within democratic frameworks.

The establishment of the Israeli state in 1948 was accompanied by the uprooting of more than half the population living in historical Palestine. More than 7,50,000 people were forced to move from what came to be Israel to the West Bank, Gaza, Egypt, Jordan, Lebanon, and Syria. A significant number of people were also internally displaced within the newly marked Israeli territory. In order to prevent the return of the displaced people, their properties, both private and communal, were either destroyed by the Israeli state agencies or handed over to new Jewish owners.

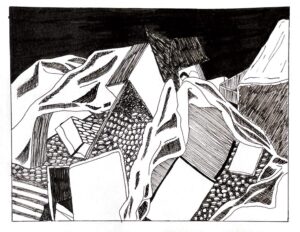

Thus began a systemised process of dispossession, displacement and ghettoisation that continued for years to come. This process particularly gained pace when the 1967 Arab-Israel war resulted in the Israeli occupation of all Palestinian territories. Over the years, the demolition of Palestinian townships, villages, farms, and houses became a perpetual feature of Israel’s Zionist project, which aimed at de-Arabisation and Judaisation of Palestinian lands.

In India too, state-sanctioned demolition of properties is an age-old phenomenon. It has been directed chiefly against slum dwellers in urban areas and the Adivasis—indigenous communities—living in the hills and forests. These kinds of demolitions, justified as parts of development projects or by citing encroachment of state land, have been quite well documented.

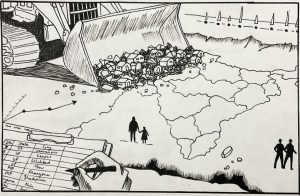

However, recent years have witnessed a sharp surge in punitive state-led demolitions. State agencies carry out these demolitions as punishment for alleged crimes of arson and vandalism or against people involved in protests against state actions. Human rights organisations, such as Amnesty International, point out that these punitive demolitions have been directed against the largest religious minority of the country—the Muslims. Ironically, christened as “bulldozer justice” by the Indian media, this politically motivated bulldozing of structures has been popularised by the right-wing Bharatiya Janata Party governments, both at the level of central and state governments.

“Bulldozer justice” has been widely covered and debated in the country’s television, print and digital media. Civil society groups, human rights advocates, and even the courts have called these demolitions arbitrary, discriminatory and illegal. Authors like Shivangi Mariam Raj and Somdeep Sen have argued that these weaponised demolitions in India have, at least to some extent, been inspired by the Israeli treatment of Palestinian land, buildings and people. While the historical context and scale of demolitions by the Israeli and Indian states are widely different, the similar nature of discriminatory demolition targeting specific communities mandates a comparison, especially across two possible registers: state rhetoric surrounding the demolition and the affected population’s responses to these violations.

Justifications behind demolitions

In general, Israeli authorities offer three types of justifications for carrying out demolitions of Palestinian structures and erecting illegal settlements and outposts. The first is a bureaucratic one that targets Palestinian properties in Occupied Palestinian Territories, especially in the governorates of Jerusalem, Tulkarm, and Hebron, for not having proper building permits; this makes the consequent evictions development-induced.

Israel recognises punitive demolitions as a method of law and order implementation. Except for a brief suspension of punitive demolitions from 2005-2014, it has been a part of official state policy that the courts have repeatedly approved. Such demolition of Palestinian structures initially emerged as a consequence of an emergency law introduced in the final years of the British Mandate in Palestine in 1945. This law allowed the destruction of a house or land from which the Israeli military suspected an enemy attack to have been carried out. Reproduction of similar practices by the Israeli administration in the form of punitive demolitions, along with other kinds of architectural violence, continues to this date.

Israeli authorities, for instance, carried out a large number of punitive destruction of Palestinian structures during the Second Intifada, from 2000-2005, when Palestinians rose up against Israeli occupation. According to Jerusalem-based Human Rights group B’Tselem, in that period, close to a thousand Palestinian homes were deemed illegal and demolished by the civilian administration, citing a lack of official building permits.

In the same period, another 628 Palestinian homes were destroyed as collective punishment, targeting the homes of people suspected or known to be involved in what Israel deems as terrorism. This forms the second justification for the evictions, which is conflict-induced. Thus, Palestinian structures were rendered illegal either by questioning the legitimacy of their paperwork or by establishing a connection with someone involved in violent actions against Israel or its citizens. The third justification for demolitions is based on Israel’s logic of security, presenting demolitions around roads and Jewish settlements as a military necessity, aiming at greater security for the Israeli state and people.

While such punitive demolition is part of state policy in Israel, it still has to be done in the garb of anti-encroachment drives in India. The state representatives in India provide two kinds of justifications. One is the official justification documented in records and presented to the courts when the legality of such actions is questioned. The other is the popular justification, which is delivered verbally at public rallies, speeches, or on social media and directed exclusively at the common public. This is also done to garner public support for the practice of demolitions of Muslim-owned properties.

The punitive demolitions in India usually take place after instances of communal violence or protests, and intend to punish the alleged perpetrators without waiting for the courts to adjudge on the matter. Authorities often cite urban development, beautification drives, or clearing of “illegal encroachments” as reasons behind the demolitions while publicly pitching them as punitive measures against activists, protestors, and government critics. However, the punitive justification is strictly directed towards the public, while the bureaucratic justification is directed towards the courts of justice. The Uttar Pradesh government, which has been in the news often for carrying out punitive demolitions of Muslim houses, has denied in front of the apex court that the demolitions were retaliatory or targeted people of any particular community. These two modes of justification work hand in hand to carry out the demolitions.

The judicial process for justice for Palestinians who have faced demolitions is nearly farcical. The Israeli courts started hearing cases of forced evictions and demolition of Palestinian properties in the 1970s after the occupation of West Bank, Jerusalem and Gaza in the 1967 war. In the initial phase, while the Israeli courts mostly acted as the legitimising vehicle for the land-grabbing actions of the state, they did occasionally rule against the actions of the military and the settlers. An illustration of such an overruling is the 1979 Elon Moreh case, where the Israeli High Court adjudged the land seizure ordered by the Israeli army illegal. As a result, the settlement built on the confiscated land had to be evacuated and removed. Such cases were, however, rare and ended up contributing to legitimising the actions of the Israeli state by painting a veneer of democracy and rule of law over the occupation.

The Tel Aviv-based legal scholar Ronen Shamir, in his paper published in the Law and Society Review, noted that in similar matters following Elon Moreh’s case, the court expanded the limits of “security reasons” and “military necessities,” providing justifications for the Israeli state’s demolition policies. Even in the Elon Moreh judgement, the court suggested that future land seizure orders could adopt the pattern of declaring lands as “state lands,” promising that it would refuse to inquire into the validity of such declarations. Shamir noted that after the Elon Moreh case, the number of petitions by Palestinians dropped significantly, and the few that got submitted were dismissed. There were not many instances of the Israeli High Court of Justice granting a petition filed by a Palestinian against the proposed demolition of their house. Between 1967 and 1986, 557 petitions were submitted to the Israeli High Court of Justice related to matters of land and property confiscations and seizures, along with other matters like taxation, work permits and detentions. From the 557 cases filed, only 65 reached the stage of adjudication, while only in five cases, few of the arguments made by the petitioners were upheld.

On the other hand, the Indian high courts have rejected the bureaucratic justification of demolitions several times when there seemed to be punitive motives behind them. The Guwahati High Court, in July 2022, initiated a sou motu case after properties belonging to five men, who had been accused of burning a police station, were bulldozed. In this case, the bench directed the BJP-led state government to compensate the affected parties. Similarly, in August 2022, the Delhi High Court chastised the Delhi Development Authority for failing to follow due process and issue notices before showing up at the doorsteps of people with bulldozers in the name of anti-encroachment drive. The anti-Muslim bias of the BJP-led state governments has been so blatant that the Haryana High Court in 2023 had to ask the state authorities if, through conducting discriminatory demolitions in a riot-hit district, they were engaging in the practice of ethnic cleansing.

However, it is pertinent to note that these judicial interventions usually occur after the demolition has taken place. They never initiate any prosecution against the erring officials, and, in most cases, do not direct the payment of compensation to individuals and families whose homes have been reduced to rubble. As a result, the Indian judiciary has often delivered a rap on the knuckles, but it has rarely gone beyond that, effectively allowing the practice to continue. Even after a Supreme Court judgment last year harshly denounced extrajudicial demolitions, terming it illegal collective punishment and issuing detailed guidelines to prevent it, state governments have already resumed the practice.

There are aspects of state-authored demolitions both in Palestine and India that cannot be entirely explained by the justifications provided by the state. In Palestine, for instance, the evictions and destruction are not just limited to residential areas. The Israeli authorities have been involved in destroying olive and citrus orchards, digging up irrigation pipes, and damaging crops. They have also taken control of almost half of the arable farmland in the West Bank and more than half of its aquifers and wells. These acts are hard to explain using the logic of security, bureaucracy or development. The goal seems to be the complete elimination of life as it exists in Palestinian villages and townships and ridding the landscape of its Arab history.

In the case of the new kind of demolitions in India, there seem to be unstated reasons going beyond the overtly stated causes of land encroachment and lack of building permits, and even the thinly veiled justification of punishment for communal violence and anti-government protests. In a report that documented and analysed the recent extrajudicial demolitions in five Indian states, Amnesty International noted that these demolitions were not just directed at individuals allegedly involved in protests or communal violence but rather at the broader Muslim community. They targeted Muslim businesses, properties, and places of worship. These demolition drives were carried out in Muslim-majority localities, and Muslim-owned properties were selectively targeted in areas inhabited by multiple communities.

Indian high courts have rejected the bureaucratic justification of demolitions several times when there seemed to be punitive motives behind them. Representational image by Ritesh Uttamchandani.

Responses of targeted communities

While there are definite similarities between the states’ logic and rhetoric concerning the demolitions in India and Palestine, the responses of the affected populations seem to be drastically different from each other. The Palestinian resistance to the demolition of their homes, appropriation of their lands and forced evictions is informed by the ideological theme of Sumud (steadfastness). Devised after the occupation of Palestine in 1967 as a middle path between violent insurgency and passivity, Sumud is a form of nonviolent resistance that denotes the determination to stay on one’s land in the face of difficulty and uncertainty.

In Palestinian areas where demolition or its threat has become a regular part of everyday lives, Sumud can manifest in various ways—such as refusing to leave when a demolition notice is served, rebuilding destroyed properties at the very site of their demolition or rebuilding structures as close to the original site as possible. In the areas that are internationally recognised as Palestinian territory, it is almost impossible to get a building permit, especially in Area C of the West Bank and East Jerusalem, forcing growing families either to build new structures without official permissions from the Israeli authority or to make unauthorised extensions to existing structures. The strictness of the permit regime that the Palestinians have to operate under can be understood from the following instance: between 2010 and 2012, 94% of the 3,750 requests for planning permission by Palestinians were denied. Almost every structure that Palestinians build or extend, thus, is automatically deemed illegal and is vulnerable to possible state-sanctioned demolition. Moreover, Palestinians also have to pay court fines for “illegal” buildings and even pay thousands of dollars for the demolition process itself.

Once the structure is demolished, since there is minimal possibility of legal relief for the affected party, the residents rebuild the destroyed houses, knowing fully well that the bulldozers can return anytime. The Palestinian relation to the built structures is thus secondary to their relation to the land. Architectural Sumud is a defiant practice of spatial resistance, which challenges the hegemony of the state that makes it illegal for the Palestinians to build on their own land. Reconstruction as resistance is a practice that is followed not only by affected Palestinian individuals but by the Palestinian government as well. In June 2023, when the Israeli army blew up the house of a Palestinian prisoner, Islam Faroukh, in Ramallah, the Palestinian prime minister Mohammed Shtayyeh promised to “rebuild every house destroyed by the occupation.” These reconstructions are often done as a necessity because the displaced people are in immediate need of homes, but these inevitably end up challenging the power of the state irrespective of their original intent.

Since discriminatory punitive demolitions are a relatively new phenomenon in India, only time will discern the collective response of the affected community. For now, at the individual as well as the collective level, it seems that the victims of extra-legal demolitions have put their faith in the judiciary. Trying to get the demolitions halted when there is enough time to challenge the orders or to question the legality of demolitions after they have been carried out has been the course chosen by individuals, religious organisations, as well as opposition party members who have taken a strong stance against the arbitrariness and illegality of ‘bulldozer justice.’

Jamiat Ulema-e-Hind, an organisation of religious Muslim scholars in India, has taken the lead in challenging the extrajudicial demolitions in various high courts and the Supreme Court of India. A plea by this organisation led to the apex court effectively banning punitive demolitions in November 2024. Individually, many victims of extrajudicial demolitions have also moved the courts seeking compensation or relief. The high courts are yet to deliver judgements on these compensation claims.

Overall, while there is significant debate about whether the judiciary could have intervened in cases of punitive demolitions much earlier, it has, at the highest level, adjudged in favour of the victims and called out the excesses of the state. The Supreme Court said it would be wholly impermissible for the state to decide that demolition can be a punishment for an accused person. “The executive cannot replace the judiciary in performing its core functions,” the court said. The SC judgement was seen as a victory by the victims and opponents of ‘bulldozer justice.’ There was also hope that it would act as a precedent and lead to the grant of compensation in the other cases pending in High Courts. However, recently, some state governments have started exploiting loopholes in the Supreme Court judgement and have started punitive demolitions again. How the court responds to this resumption remains to be seen.

Related Posts

Architectural violence: State-sanctioned demolitions in Palestine and India

State-sanctioned demolitions are distinct and powerful tools of control and punishment in both Israel and India, targeting specific marginalised communities in these disparate geographies. While operating in vastly different historical and political contexts, both nations have weaponised demolition policies against the communities they see as the Other—Palestinians in Israeli occupied lands, and Muslims in India. These demolitions function as expressions of state control, revealing striking parallels in their justifications and implementations, while also underlining the differences in the respective practices in Palestine and India. By comparing these practices, what emerges is the understanding of how architectural violence becomes institutionalised within democratic frameworks.

The establishment of the Israeli state in 1948 was accompanied by the uprooting of more than half the population living in historical Palestine. More than 7,50,000 people were forced to move from what came to be Israel to the West Bank, Gaza, Egypt, Jordan, Lebanon, and Syria. A significant number of people were also internally displaced within the newly marked Israeli territory. In order to prevent the return of the displaced people, their properties, both private and communal, were either destroyed by the Israeli state agencies or handed over to new Jewish owners.

Thus began a systemised process of dispossession, displacement and ghettoisation that continued for years to come. This process particularly gained pace when the 1967 Arab-Israel war resulted in the Israeli occupation of all Palestinian territories. Over the years, the demolition of Palestinian townships, villages, farms, and houses became a perpetual feature of Israel’s Zionist project, which aimed at de-Arabisation and Judaisation of Palestinian lands.

In India too, state-sanctioned demolition of properties is an age-old phenomenon. It has been directed chiefly against slum dwellers in urban areas and the Adivasis—indigenous communities—living in the hills and forests. These kinds of demolitions, justified as parts of development projects or by citing encroachment of state land, have been quite well documented.

However, recent years have witnessed a sharp surge in punitive state-led demolitions. State agencies carry out these demolitions as punishment for alleged crimes of arson and vandalism or against people involved in protests against state actions. Human rights organisations, such as Amnesty International, point out that these punitive demolitions have been directed against the largest religious minority of the country—the Muslims. Ironically, christened as “bulldozer justice” by the Indian media, this politically motivated bulldozing of structures has been popularised by the right-wing Bharatiya Janata Party governments, both at the level of central and state governments.

“Bulldozer justice” has been widely covered and debated in the country’s television, print and digital media. Civil society groups, human rights advocates, and even the courts have called these demolitions arbitrary, discriminatory and illegal. Authors like Shivangi Mariam Raj and Somdeep Sen have argued that these weaponised demolitions in India have, at least to some extent, been inspired by the Israeli treatment of Palestinian land, buildings and people. While the historical context and scale of demolitions by the Israeli and Indian states are widely different, the similar nature of discriminatory demolition targeting specific communities mandates a comparison, especially across two possible registers: state rhetoric surrounding the demolition and the affected population’s responses to these violations.

Justifications behind demolitions

In general, Israeli authorities offer three types of justifications for carrying out demolitions of Palestinian structures and erecting illegal settlements and outposts. The first is a bureaucratic one that targets Palestinian properties in Occupied Palestinian Territories, especially in the governorates of Jerusalem, Tulkarm, and Hebron, for not having proper building permits; this makes the consequent evictions development-induced.

Israel recognises punitive demolitions as a method of law and order implementation. Except for a brief suspension of punitive demolitions from 2005-2014, it has been a part of official state policy that the courts have repeatedly approved. Such demolition of Palestinian structures initially emerged as a consequence of an emergency law introduced in the final years of the British Mandate in Palestine in 1945. This law allowed the destruction of a house or land from which the Israeli military suspected an enemy attack to have been carried out. Reproduction of similar practices by the Israeli administration in the form of punitive demolitions, along with other kinds of architectural violence, continues to this date.

Israeli authorities, for instance, carried out a large number of punitive destruction of Palestinian structures during the Second Intifada, from 2000-2005, when Palestinians rose up against Israeli occupation. According to Jerusalem-based Human Rights group B’Tselem, in that period, close to a thousand Palestinian homes were deemed illegal and demolished by the civilian administration, citing a lack of official building permits.

In the same period, another 628 Palestinian homes were destroyed as collective punishment, targeting the homes of people suspected or known to be involved in what Israel deems as terrorism. This forms the second justification for the evictions, which is conflict-induced. Thus, Palestinian structures were rendered illegal either by questioning the legitimacy of their paperwork or by establishing a connection with someone involved in violent actions against Israel or its citizens. The third justification for demolitions is based on Israel’s logic of security, presenting demolitions around roads and Jewish settlements as a military necessity, aiming at greater security for the Israeli state and people.

While such punitive demolition is part of state policy in Israel, it still has to be done in the garb of anti-encroachment drives in India. The state representatives in India provide two kinds of justifications. One is the official justification documented in records and presented to the courts when the legality of such actions is questioned. The other is the popular justification, which is delivered verbally at public rallies, speeches, or on social media and directed exclusively at the common public. This is also done to garner public support for the practice of demolitions of Muslim-owned properties.

The punitive demolitions in India usually take place after instances of communal violence or protests, and intend to punish the alleged perpetrators without waiting for the courts to adjudge on the matter. Authorities often cite urban development, beautification drives, or clearing of “illegal encroachments” as reasons behind the demolitions while publicly pitching them as punitive measures against activists, protestors, and government critics. However, the punitive justification is strictly directed towards the public, while the bureaucratic justification is directed towards the courts of justice. The Uttar Pradesh government, which has been in the news often for carrying out punitive demolitions of Muslim houses, has denied in front of the apex court that the demolitions were retaliatory or targeted people of any particular community. These two modes of justification work hand in hand to carry out the demolitions.

The judicial process for justice for Palestinians who have faced demolitions is nearly farcical. The Israeli courts started hearing cases of forced evictions and demolition of Palestinian properties in the 1970s after the occupation of West Bank, Jerusalem and Gaza in the 1967 war. In the initial phase, while the Israeli courts mostly acted as the legitimising vehicle for the land-grabbing actions of the state, they did occasionally rule against the actions of the military and the settlers. An illustration of such an overruling is the 1979 Elon Moreh case, where the Israeli High Court adjudged the land seizure ordered by the Israeli army illegal. As a result, the settlement built on the confiscated land had to be evacuated and removed. Such cases were, however, rare and ended up contributing to legitimising the actions of the Israeli state by painting a veneer of democracy and rule of law over the occupation.

The Tel Aviv-based legal scholar Ronen Shamir, in his paper published in the Law and Society Review, noted that in similar matters following Elon Moreh’s case, the court expanded the limits of “security reasons” and “military necessities,” providing justifications for the Israeli state’s demolition policies. Even in the Elon Moreh judgement, the court suggested that future land seizure orders could adopt the pattern of declaring lands as “state lands,” promising that it would refuse to inquire into the validity of such declarations. Shamir noted that after the Elon Moreh case, the number of petitions by Palestinians dropped significantly, and the few that got submitted were dismissed. There were not many instances of the Israeli High Court of Justice granting a petition filed by a Palestinian against the proposed demolition of their house. Between 1967 and 1986, 557 petitions were submitted to the Israeli High Court of Justice related to matters of land and property confiscations and seizures, along with other matters like taxation, work permits and detentions. From the 557 cases filed, only 65 reached the stage of adjudication, while only in five cases, few of the arguments made by the petitioners were upheld.

On the other hand, the Indian high courts have rejected the bureaucratic justification of demolitions several times when there seemed to be punitive motives behind them. The Guwahati High Court, in July 2022, initiated a sou motu case after properties belonging to five men, who had been accused of burning a police station, were bulldozed. In this case, the bench directed the BJP-led state government to compensate the affected parties. Similarly, in August 2022, the Delhi High Court chastised the Delhi Development Authority for failing to follow due process and issue notices before showing up at the doorsteps of people with bulldozers in the name of anti-encroachment drive. The anti-Muslim bias of the BJP-led state governments has been so blatant that the Haryana High Court in 2023 had to ask the state authorities if, through conducting discriminatory demolitions in a riot-hit district, they were engaging in the practice of ethnic cleansing.

However, it is pertinent to note that these judicial interventions usually occur after the demolition has taken place. They never initiate any prosecution against the erring officials, and, in most cases, do not direct the payment of compensation to individuals and families whose homes have been reduced to rubble. As a result, the Indian judiciary has often delivered a rap on the knuckles, but it has rarely gone beyond that, effectively allowing the practice to continue. Even after a Supreme Court judgment last year harshly denounced extrajudicial demolitions, terming it illegal collective punishment and issuing detailed guidelines to prevent it, state governments have already resumed the practice.

There are aspects of state-authored demolitions both in Palestine and India that cannot be entirely explained by the justifications provided by the state. In Palestine, for instance, the evictions and destruction are not just limited to residential areas. The Israeli authorities have been involved in destroying olive and citrus orchards, digging up irrigation pipes, and damaging crops. They have also taken control of almost half of the arable farmland in the West Bank and more than half of its aquifers and wells. These acts are hard to explain using the logic of security, bureaucracy or development. The goal seems to be the complete elimination of life as it exists in Palestinian villages and townships and ridding the landscape of its Arab history.

In the case of the new kind of demolitions in India, there seem to be unstated reasons going beyond the overtly stated causes of land encroachment and lack of building permits, and even the thinly veiled justification of punishment for communal violence and anti-government protests. In a report that documented and analysed the recent extrajudicial demolitions in five Indian states, Amnesty International noted that these demolitions were not just directed at individuals allegedly involved in protests or communal violence but rather at the broader Muslim community. They targeted Muslim businesses, properties, and places of worship. These demolition drives were carried out in Muslim-majority localities, and Muslim-owned properties were selectively targeted in areas inhabited by multiple communities.

Indian high courts have rejected the bureaucratic justification of demolitions several times when there seemed to be punitive motives behind them. Representational image by Ritesh Uttamchandani.

Responses of targeted communities

While there are definite similarities between the states’ logic and rhetoric concerning the demolitions in India and Palestine, the responses of the affected populations seem to be drastically different from each other. The Palestinian resistance to the demolition of their homes, appropriation of their lands and forced evictions is informed by the ideological theme of Sumud (steadfastness). Devised after the occupation of Palestine in 1967 as a middle path between violent insurgency and passivity, Sumud is a form of nonviolent resistance that denotes the determination to stay on one’s land in the face of difficulty and uncertainty.

In Palestinian areas where demolition or its threat has become a regular part of everyday lives, Sumud can manifest in various ways—such as refusing to leave when a demolition notice is served, rebuilding destroyed properties at the very site of their demolition or rebuilding structures as close to the original site as possible. In the areas that are internationally recognised as Palestinian territory, it is almost impossible to get a building permit, especially in Area C of the West Bank and East Jerusalem, forcing growing families either to build new structures without official permissions from the Israeli authority or to make unauthorised extensions to existing structures. The strictness of the permit regime that the Palestinians have to operate under can be understood from the following instance: between 2010 and 2012, 94% of the 3,750 requests for planning permission by Palestinians were denied. Almost every structure that Palestinians build or extend, thus, is automatically deemed illegal and is vulnerable to possible state-sanctioned demolition. Moreover, Palestinians also have to pay court fines for “illegal” buildings and even pay thousands of dollars for the demolition process itself.

Once the structure is demolished, since there is minimal possibility of legal relief for the affected party, the residents rebuild the destroyed houses, knowing fully well that the bulldozers can return anytime. The Palestinian relation to the built structures is thus secondary to their relation to the land. Architectural Sumud is a defiant practice of spatial resistance, which challenges the hegemony of the state that makes it illegal for the Palestinians to build on their own land. Reconstruction as resistance is a practice that is followed not only by affected Palestinian individuals but by the Palestinian government as well. In June 2023, when the Israeli army blew up the house of a Palestinian prisoner, Islam Faroukh, in Ramallah, the Palestinian prime minister Mohammed Shtayyeh promised to “rebuild every house destroyed by the occupation.” These reconstructions are often done as a necessity because the displaced people are in immediate need of homes, but these inevitably end up challenging the power of the state irrespective of their original intent.

Since discriminatory punitive demolitions are a relatively new phenomenon in India, only time will discern the collective response of the affected community. For now, at the individual as well as the collective level, it seems that the victims of extra-legal demolitions have put their faith in the judiciary. Trying to get the demolitions halted when there is enough time to challenge the orders or to question the legality of demolitions after they have been carried out has been the course chosen by individuals, religious organisations, as well as opposition party members who have taken a strong stance against the arbitrariness and illegality of ‘bulldozer justice.’

Jamiat Ulema-e-Hind, an organisation of religious Muslim scholars in India, has taken the lead in challenging the extrajudicial demolitions in various high courts and the Supreme Court of India. A plea by this organisation led to the apex court effectively banning punitive demolitions in November 2024. Individually, many victims of extrajudicial demolitions have also moved the courts seeking compensation or relief. The high courts are yet to deliver judgements on these compensation claims.

Overall, while there is significant debate about whether the judiciary could have intervened in cases of punitive demolitions much earlier, it has, at the highest level, adjudged in favour of the victims and called out the excesses of the state. The Supreme Court said it would be wholly impermissible for the state to decide that demolition can be a punishment for an accused person. “The executive cannot replace the judiciary in performing its core functions,” the court said. The SC judgement was seen as a victory by the victims and opponents of ‘bulldozer justice.’ There was also hope that it would act as a precedent and lead to the grant of compensation in the other cases pending in High Courts. However, recently, some state governments have started exploiting loopholes in the Supreme Court judgement and have started punitive demolitions again. How the court responds to this resumption remains to be seen.

SUPPORT US

We like bringing the stories that don’t get told to you. For that, we need your support. However small, we would appreciate it.