The common silences and refrains that follow punitive demolitions

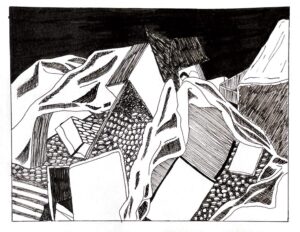

On a hot afternoon in a city that must remain unnamed, a young woman walked me through the rubble of what used to be her home. Or rather, she stood at a distance, pointed, and said, “It was here.” Then, she fell silent. Her voice did not crack, her body did not shake. She just stood there, motionless. “We’ve already left it to Allah,” she said later, her eyes still fixed on the ground, “there’s no point saying anything to anyone else now.”

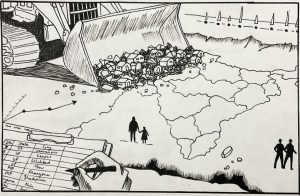

During the documentation work for The Demolitions Project, these silences are not uncommon. Our archive of extrajudicial and punitive demolitions across India is marked not only by what has been recorded but by the absences that surround the recorded material: the stories people could not tell, would not tell, or asked us never to share. These absences are not gaps in the research; they are artefacts of violence. They reveal the fear, exhaustion, and hopelessness that often follow the destruction of one’s home at the hands of the state.

We began this work with the intention of documenting and bearing witness to a growing pattern of punitive demolitions disproportionately targeting Muslim communities in India. But early into the project, it became clear that while gathering visual evidence and tracing legal trails were important, the most fragile and essential work lay elsewhere: in building trust, listening, and honouring refusal. Many families who saw their homes reduced to debris did not want to speak—not out of indifference, but out of fear, or resignation, or both. In this context, it is important to sit with that refusal, to understand what these silences tell us about the nature of state violence, the weight of trauma, and the impossibility of seeking justice in a system that has already declared you undeserving of it.

“Please don’t write anything that might affect our case”

One family we spoke to had filed a writ petition in court against the demolition of their property. They agreed to talk to us, cautiously, after weeks of back-and-forth. On a phone call that spanned several hours, speaking with them through a relative’s mobile phone, the family described what had happened in careful, legal terms. The father kept repeating, “Please don’t write anything that might affect our case.” When handed back his phone, the relative said, “You know, we don’t know what helps or hurts anymore. We’ve seen the truth twisted so many times. We just want to survive.”

They were not wrong. In a system where even truth can become a liability, speaking is a dangerous act. State narratives often frame demolitions as administrative action, part of an urban renewal process, or as punitive responses to alleged crimes. Media complicity ensures that these demolitions are viewed not as violations, but as just deserts. In such an environment, even documentation becomes risky, and even solidarity, suspect.

In one case, the silence is driven by pure fear. One family said they had been warned by local authorities not to speak. In another incident, after our first visit, the family received a phone call from an “unknown number” instructing them to “not invite trouble.” The next time we visited, they declined to meet us. “We don’t want any new trouble,” a neighbour explained on their behalf. This chilling reality of surveillance and retaliation haunts our documentation process. In villages and towns where informers are common and loyalties are fragile, even being seen talking to someone perceived as an outsider can be dangerous. For some families, their choice is simple: silence is safer.

“We’ve lost everything; what will talking do?”

“Humne sab kuch kho diya”—We’ve lost everything—said a young man in Madhya Pradesh, whose entire home was razed after his neighbourhood was communally targeted. “Aap se baat karke kya hoga?” (What will talking to you achieve?) It was not a dismissal. It was the voice of someone who had spent months navigating police stations, lawyers’ offices, municipal records, and rental homes. He had spoken, and spoken, and spoken; to journalists, to activists, to his neighbours. Nothing changed. The bulldozers had done their job. The state had won. Speaking now, again, felt like an exercise in futility.

This sentiment has surfaced repeatedly. After the home is demolished, after the case has gone viral, after the outrage cycle ends, what remains for the families is not justice but the long, slow burden of survival. Some have managed to rebuild. Most have not. Some are still in litigation. Others, too tired to keep fighting, have stopped. The silence is not a lack of resistance, it is a shift in survival strategy. One family member told me, “We speak to no one now. We can’t afford more trouble.”

“We’ve put our complaints before our Lord”

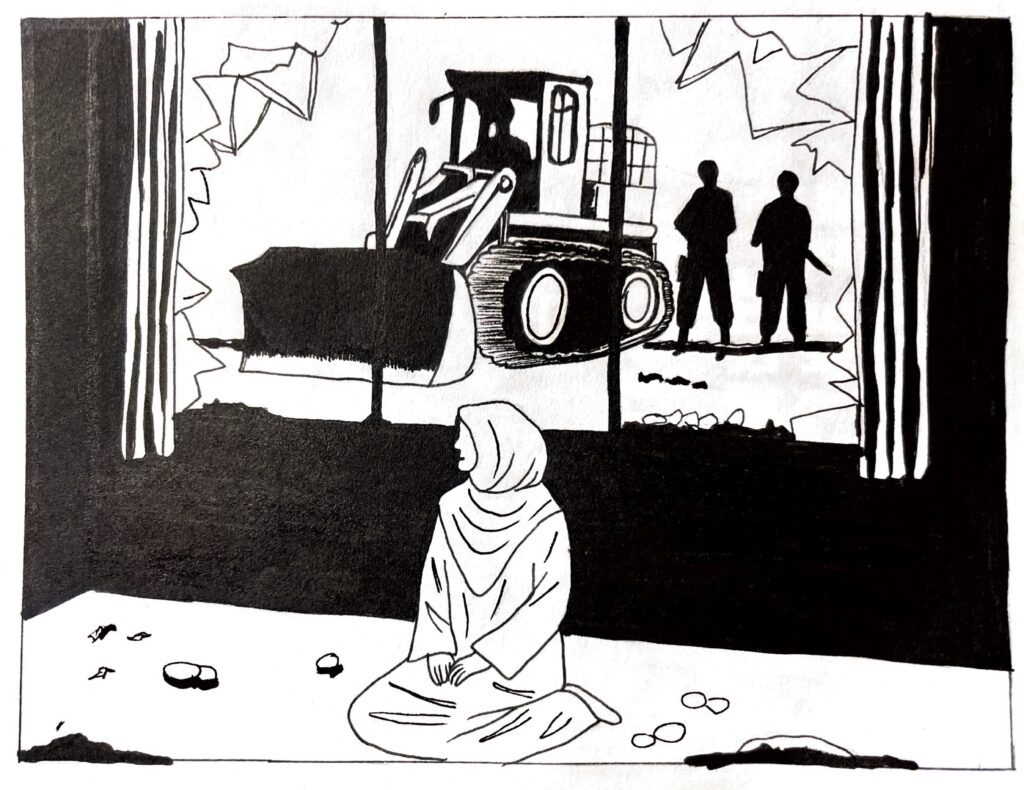

For many families, the act of surrender is not just emotional but spiritual. A woman in Uttar Pradesh, when approached for an interview, said gently but firmly: “We’ve put our complaints before our Lord. He will do justice. We don’t want to talk anymore.” For her, speaking to the press, or to researchers for this project, felt like doubting divine justice. What could earthly validation offer when divine justice had already been invoked?

There is a language here that secular frameworks often miss. The refusal to speak is not just silence, it is submission to a different court, a court higher than the state. It is, in some cases, a refusal to legitimise the legal system that wronged them. One man, when pressed gently about whether he would consider telling his story, said, “When even the courts don’t follow their own laws, who are we to argue?”

This spiritual framework can be empowering. It offers a sense of closure, a way to retain dignity in the face of helplessness. But it also acts, sometimes, as a final wall between the survivors and the public record.

“Talking about it brings it all back”

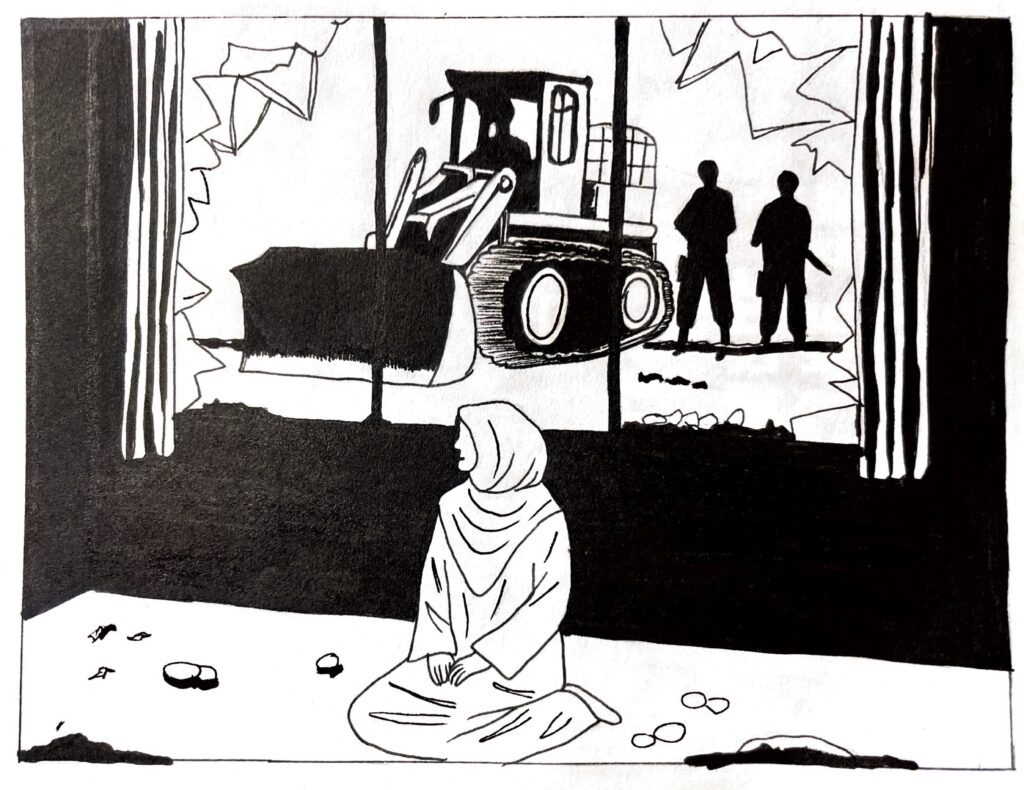

The trauma of losing one’s home is not just material—it is psychological, social, and generational. But the violence does not stop with the demolition. The act of retelling can itself be retraumatising. We’ve had people begin interviews only to stop halfway, their voices shaking. Others ask to remain anonymous, not just to protect their identity, but because they don’t want to remember. “We’ve moved on,” one mother said. “Talking about it brings it all back.”

Tauheed Fatima, whose case we documented in Prayagraj, faced the demolition of her home under the pretense of an illegal construction, days before she was to move in. Her father Junaid recounted every procedural violation with heartbreaking precision. Tauheed, however, could never articulate what she felt. The loss seemed too vast to encapsulate in language. “I still don’t believe it happened,” she told us. “We waited so long for this home. And now it’s gone.” Through this project, we’ve come to understand that witnessing isn’t just about recording. It’s also about listening to what cannot be said, respecting what must remain unsaid, and holding space for grief that has no tidy resolution.

In liberal democratic discourse, silence is often equated with submission. But in the context of demolition survivors, silence can also be a strategy—a way to retain some control when everything else has been taken. It can be an assertion of autonomy: that the state took their homes, but it will not take their words. It can be a refusal to participate in a system that destroyed them. One woman said: “They want us to beg. They want us to ask for mercy. But we will not give them the satisfaction. We will be quiet. But that quiet will be ours.”

There is power in this, too.

As researchers, journalists, and activists, we must constantly negotiate our own role in this terrain. What does it mean to ask someone to revisit their trauma? How do we balance the urgency of public record with the ethics of care? We do not publish every story we gather. Sometimes we write down nothing. Sometimes we delete audio files at the request of a family. We blur photos, anonymise names, and wait months for consent. We’ve left interviews incomplete because a survivor no longer felt safe continuing. These decisions are not just about protocol—they are political choices rooted in the belief that documentation must never come at the cost of dignity. We have also come to accept that some stories will never be told. And that’s okay. The archive, as it grows, will always carry its silences. We do not seek to fill those silences. We seek to honour them.

But there is a danger in romanticising silence. Not every refusal is empowered. Some are coerced. Some are shaped by trauma so deep it chokes language itself. Some are born of exhaustion, fear, despair. These silences are not always chosen. They are forced. But recognising that does not mean violating them. This work would not be possible without the trust of survivors, and we remain committed to documenting with care, consent, and dignity.

When a state demolishes a home, it sends a message: You do not belong here; you will not be heard. Our work exists in defiance of that message. But defiance need not always be loud. Sometimes it looks like standing with someone in silence, and letting that silence speak for itself.

Related Posts

The common silences and refrains that follow punitive demolitions

On a hot afternoon in a city that must remain unnamed, a young woman walked me through the rubble of what used to be her home. Or rather, she stood at a distance, pointed, and said, “It was here.” Then, she fell silent. Her voice did not crack, her body did not shake. She just stood there, motionless. “We’ve already left it to Allah,” she said later, her eyes still fixed on the ground, “there’s no point saying anything to anyone else now.”

During the documentation work for The Demolitions Project, these silences are not uncommon. Our archive of extrajudicial and punitive demolitions across India is marked not only by what has been recorded but by the absences that surround the recorded material: the stories people could not tell, would not tell, or asked us never to share. These absences are not gaps in the research; they are artefacts of violence. They reveal the fear, exhaustion, and hopelessness that often follow the destruction of one’s home at the hands of the state.

We began this work with the intention of documenting and bearing witness to a growing pattern of punitive demolitions disproportionately targeting Muslim communities in India. But early into the project, it became clear that while gathering visual evidence and tracing legal trails were important, the most fragile and essential work lay elsewhere: in building trust, listening, and honouring refusal. Many families who saw their homes reduced to debris did not want to speak—not out of indifference, but out of fear, or resignation, or both. In this context, it is important to sit with that refusal, to understand what these silences tell us about the nature of state violence, the weight of trauma, and the impossibility of seeking justice in a system that has already declared you undeserving of it.

“Please don’t write anything that might affect our case”

One family we spoke to had filed a writ petition in court against the demolition of their property. They agreed to talk to us, cautiously, after weeks of back-and-forth. On a phone call that spanned several hours, speaking with them through a relative’s mobile phone, the family described what had happened in careful, legal terms. The father kept repeating, “Please don’t write anything that might affect our case.” When handed back his phone, the relative said, “You know, we don’t know what helps or hurts anymore. We’ve seen the truth twisted so many times. We just want to survive.”

They were not wrong. In a system where even truth can become a liability, speaking is a dangerous act. State narratives often frame demolitions as administrative action, part of an urban renewal process, or as punitive responses to alleged crimes. Media complicity ensures that these demolitions are viewed not as violations, but as just deserts. In such an environment, even documentation becomes risky, and even solidarity, suspect.

In one case, the silence is driven by pure fear. One family said they had been warned by local authorities not to speak. In another incident, after our first visit, the family received a phone call from an “unknown number” instructing them to “not invite trouble.” The next time we visited, they declined to meet us. “We don’t want any new trouble,” a neighbour explained on their behalf. This chilling reality of surveillance and retaliation haunts our documentation process. In villages and towns where informers are common and loyalties are fragile, even being seen talking to someone perceived as an outsider can be dangerous. For some families, their choice is simple: silence is safer.

“We’ve lost everything; what will talking do?”

“Humne sab kuch kho diya”—We’ve lost everything—said a young man in Madhya Pradesh, whose entire home was razed after his neighbourhood was communally targeted. “Aap se baat karke kya hoga?” (What will talking to you achieve?) It was not a dismissal. It was the voice of someone who had spent months navigating police stations, lawyers’ offices, municipal records, and rental homes. He had spoken, and spoken, and spoken; to journalists, to activists, to his neighbours. Nothing changed. The bulldozers had done their job. The state had won. Speaking now, again, felt like an exercise in futility.

This sentiment has surfaced repeatedly. After the home is demolished, after the case has gone viral, after the outrage cycle ends, what remains for the families is not justice but the long, slow burden of survival. Some have managed to rebuild. Most have not. Some are still in litigation. Others, too tired to keep fighting, have stopped. The silence is not a lack of resistance, it is a shift in survival strategy. One family member told me, “We speak to no one now. We can’t afford more trouble.”

“We’ve put our complaints before our Lord”

For many families, the act of surrender is not just emotional but spiritual. A woman in Uttar Pradesh, when approached for an interview, said gently but firmly: “We’ve put our complaints before our Lord. He will do justice. We don’t want to talk anymore.” For her, speaking to the press, or to researchers for this project, felt like doubting divine justice. What could earthly validation offer when divine justice had already been invoked?

There is a language here that secular frameworks often miss. The refusal to speak is not just silence, it is submission to a different court, a court higher than the state. It is, in some cases, a refusal to legitimise the legal system that wronged them. One man, when pressed gently about whether he would consider telling his story, said, “When even the courts don’t follow their own laws, who are we to argue?”

This spiritual framework can be empowering. It offers a sense of closure, a way to retain dignity in the face of helplessness. But it also acts, sometimes, as a final wall between the survivors and the public record.

“Talking about it brings it all back”

The trauma of losing one’s home is not just material—it is psychological, social, and generational. But the violence does not stop with the demolition. The act of retelling can itself be retraumatising. We’ve had people begin interviews only to stop halfway, their voices shaking. Others ask to remain anonymous, not just to protect their identity, but because they don’t want to remember. “We’ve moved on,” one mother said. “Talking about it brings it all back.”

Tauheed Fatima, whose case we documented in Prayagraj, faced the demolition of her home under the pretense of an illegal construction, days before she was to move in. Her father Junaid recounted every procedural violation with heartbreaking precision. Tauheed, however, could never articulate what she felt. The loss seemed too vast to encapsulate in language. “I still don’t believe it happened,” she told us. “We waited so long for this home. And now it’s gone.” Through this project, we’ve come to understand that witnessing isn’t just about recording. It’s also about listening to what cannot be said, respecting what must remain unsaid, and holding space for grief that has no tidy resolution.

In liberal democratic discourse, silence is often equated with submission. But in the context of demolition survivors, silence can also be a strategy—a way to retain some control when everything else has been taken. It can be an assertion of autonomy: that the state took their homes, but it will not take their words. It can be a refusal to participate in a system that destroyed them. One woman said: “They want us to beg. They want us to ask for mercy. But we will not give them the satisfaction. We will be quiet. But that quiet will be ours.”

There is power in this, too.

As researchers, journalists, and activists, we must constantly negotiate our own role in this terrain. What does it mean to ask someone to revisit their trauma? How do we balance the urgency of public record with the ethics of care? We do not publish every story we gather. Sometimes we write down nothing. Sometimes we delete audio files at the request of a family. We blur photos, anonymise names, and wait months for consent. We’ve left interviews incomplete because a survivor no longer felt safe continuing. These decisions are not just about protocol—they are political choices rooted in the belief that documentation must never come at the cost of dignity. We have also come to accept that some stories will never be told. And that’s okay. The archive, as it grows, will always carry its silences. We do not seek to fill those silences. We seek to honour them.

But there is a danger in romanticising silence. Not every refusal is empowered. Some are coerced. Some are shaped by trauma so deep it chokes language itself. Some are born of exhaustion, fear, despair. These silences are not always chosen. They are forced. But recognising that does not mean violating them. This work would not be possible without the trust of survivors, and we remain committed to documenting with care, consent, and dignity.

When a state demolishes a home, it sends a message: You do not belong here; you will not be heard. Our work exists in defiance of that message. But defiance need not always be loud. Sometimes it looks like standing with someone in silence, and letting that silence speak for itself.

SUPPORT US

We like bringing the stories that don’t get told to you. For that, we need your support. However small, we would appreciate it.