Demolitions as Statecraft: How the bulldozer adapted to the Supreme Court verdict

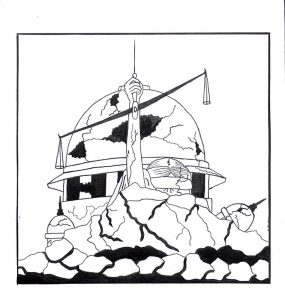

In November 2024, the Supreme Court of India pronounced what was widely hailed to be a categorical ban on the phenomenon of “bulldozer justice.” The court ruled that demolitions of homes, especially in the aftermath of communal violence or protest, must follow due process. It declared that such demolitions, if executed as punishment for an alleged crime, were unconstitutional. The ruling insisted on basic procedural safeguards: prior notice, hearing, time for appeal, and stated that demolitions could only be resorted to as the last measure. The court unequivocally condemned and prohibited collective punishments, which are inherent to the rule of bulldozer justice.

Yet, the bulldozer continues to be a normalised instrument of governance; and the judgment, far from bringing an end to the practice, became a procedural line that would be routinely crossed. In the months following the verdict, bulldozers rolled through Muslim neighbourhoods in Uttar Pradesh, Gujarat, and Maharashtra. Houses, mosques, and shrines were razed, families displaced, and entire communities marked as criminal. T his happened in spite of the law. The Supreme Court did not prohibit punitive demolitions—at best, it just framed the new contours within which they occurred. The bulldozer did not retreat, it adapted.

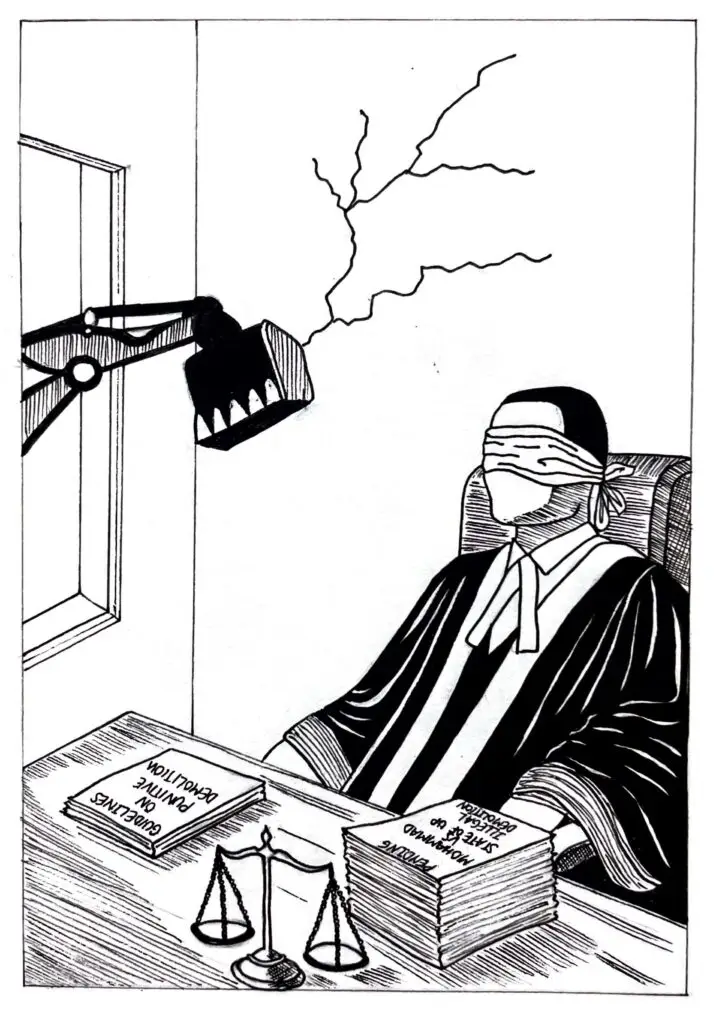

To frame these demolitions merely as violations of the Supreme Court’s guidelines is to mistake form for substance. These are not just aberrations or lapses in legal procedure; they are deliberate and structural acts of spatial violence. They are expressions of a state that asserts its power not by protecting rights, but by making its subjects disposable, especially Muslims. The bulldozer, in this context, is not a rogue machine of vengeance; it is a sanctioned tool of governance under a majoritarian regime. It is this aspect of the rule of the bulldozer that the Supreme Court failed to—or chose not to—understand, and it is why its judgment was fated for failure. The demolition of a home, a mosque, or a fishing colony becomes a public act of pedagogy. It teaches Muslims, and anyone else marked as “undesirable,” that citizenship is contingent, that shelter is conditional, that legality is arbitrary. And it teaches officials that the rule of law is negotiable, a set of optics to be managed, not limits to be obeyed.

This collapse of legal limits was especially visible in the case of the Madni Masjid demolition in Kushinagar, Uttar Pradesh. On 9 February 2025, local authorities brought in bulldozers to raze the front of a decades-old mosque. The demolition took place the very day after the expiry of a high court stay order. Officials claimed the mosque was in violation of municipal plans. But the mosque committee showed that the structure had been built on land they legally owned, and followed the building permissions granted as early as 1999. But the demolition proceeded regardless. There was no waiting for new judicial orders, no consideration of appeals.

The performance of legality had been completed: a hearing held, a notice issued, the timeline manufactured. And then, the demolition. The message was clear—even your mosque, despite your documents, can be reduced to rubble. This is not the absence of law; it is law as performance, emptied of substance and weaponised into violence. In response, the Supreme Court initiated contempt proceedings against the district officials responsible. But by then, the mosque was already scarred, its sanctity violated, its walls broken. The space had already been marked as punishable—and that punishment had already been made public. No amount of legal correction can undo that symbolic violence.

In Gujarat, where the spectacle of development has long masked the realities of exclusion, the bulldozer returned after the Supreme Court judgment with greater intensity. In January 2025, more than 250 homes and shrines were demolished on Beyt Dwarka, an island off the coast of Devbhumi Dwarka district. The government claimed this was an anti-encroachment drive aimed at protecting ecology and national security. But the reality on the ground was different.

The demolitions primarily targeted Muslim families, fishermen, traders, and shrine caretakers, many of whom had lived on the island for generations. Residents who had been living in their homes for decades reported being given just a few days’ notice. Some said they had never received a personal notice at all. The Supreme Court judgment mandated a show-cause notice period of 15 days, and another 15 days after the final demolition order, so that the affected individuals could appeal. Instead, they watched as bulldozers tore down their homes, mosques, and dargahs, while adjacent Hindu-owned structures remained untouched.

The island, a shared space of worship and habitation, was rapidly emptied of its Muslim presence—spatially cleansed under the guise of environmental order. The claim of protecting the local ecology was mobilised not to preserve land but to erase lives and served as a secular veil for communal exclusion. This is what makes “bulldozer justice” particularly insidious: it wears the language of law, order, and regulation, while reproducing the violence of the state. No meaningful rehabilitation was offered to those displaced in Beyt Dwarka. Their belongings were buried in sand, their homes flattened, their histories erased. The state did not deny what it had done; it simply insisted it was legal. And in that claim, we see the brutal efficacy of governance by demolition—where in effect, the law is neither absent nor broken, but a semblance of it is invoked and performed by the courts, only to be later discarded by the state.

In Nagpur, Maharashtra, bulldozers arrived in the aftermath of communal violence. On 17 March 2025, clashes erupted during a protest led by right-wing groups. Soon after, police arrested several Muslim men, accusing them of incitement. One of them was Fahim Khan, a local political activist. Within days, the Nagpur Municipal Corporation served demolition notices to Khan’s family. The notice gave them just 24 hours to respond. Even as Khan moved the Nagpur bench of the Bombay High Court and obtained a stay on the demolition, the municipal authority had already demolished a portion of their house, built decades earlier, claiming it was an unauthorised structure. The message, again, was not legal but symbolic: if you protest, we will punish your home.

This was not an isolated incident. Other families of Muslim men arrested in connection with the riot also received demolition notices. Some were elderly. Some had nothing to do with the violence. But their homes were marked, not because of building violations, but because of proximity to criminal accusation. This is collective punishment, rendered through the language of “unauthorised construction.” Once again, the judicial protection became meaningless. The damage had been done, the rubble was real, the fear it produced was lasting. The law came afterward, as correction, not as protection.

Across these sites, Kushinagar, Beyt Dwarka, Nagpur, the bulldozer operated not simply as a tool of destruction but as a technology of disciplining space and people. It rendered Muslim life disposable, it transformed shelter into threat, it turned accusation into conviction, and presence into encroachment. The demolitions are not always “against the law”; they are what the law becomes under a regime that marries legality to majoritarian desire. The spectacle of the bulldozer satisfies a political craving for punishment, one that does not wait for a trial, a verdict, or a sentence. It demands the immediate erasure of the accused, their family, their home and it finds in municipal statutes the perfect vehicle; neutral on paper, violent in application.

This is why the law alone cannot stop the bulldozer. Because the law, in this context, is not neutral terrain. It is not merely being misused, it is being reinterpreted, retooled, and performed as violence. As long as the state can cite regulation to justify revenge, as long as it can manufacture procedural compliance in service of ideological erasure, the bulldozer will continue to roll.

In April 2025, the Supreme Court ordered the Prayagraj Development Authority in Uttar Pradesh to pay Rs 60 lakh in compensation to six families whose homes had been illegally demolished. The demolitions took place in 2021, after anti-government protests. The state had claimed that the homes belonged to a gangster; the owners denied the allegation. The court found that no due process had been followed. Notices were served perfunctorily; demolitions conducted without hearings. Justice Abhay Oka, delivering the ruling, remarked that the demolitions “shocked the conscience of the Court.” The justices were unequivocal in their condemnation and ordered restitution. They reminded the state of the basic rights to housing and shelter. And yet, no official was held personally accountable. The compensation will come from public funds, not from the salaries or pensions of those who executed or ordered the demolitions.

This is the paradox at the heart of judicial intervention in the bulldozer regime: relief without reckoning. The courts recognised that the demolitions were illegal and offered compensation to the victims. But if they do not dismantle the infrastructure of impunity, name and penalise the officials responsible, the judiciary risks becoming a postscript to state violence—a mechanism of after-the-fact adjustment, not prevention. The cycle would thus continue. Demolitions will take place, victims will sue, and the courts may offer compensation. But bureaucrats will remain protected, and the structure of executive overreach will remain intact. The bulldozer then becomes a gamble worth taking, especially when it delivers political capital and only costs public money.

The Supreme Court’s guidelines against demolitions were meant to draw a line. It said governments must follow due process, that demolitions cannot be used as retribution and that the executive cannot replace the judiciary. Additionally, the guidelines directed municipal bodies to established digital portals within three months to document demolition orders, show-cause notices, and related procedures. This initiative aimed to enhance transparency and accountability in demolition practices. However, as of April 2025, no state government has successfully implemented such a demolition tracking website. This failure highlights significant challenges in enforceability and compliance at state level, reflecting broader issues of impunity and lack of oversight in state-led demolition activities. State governments, in their everyday operations, have refused to recognise that line. They have stepped over it, repeatedly, with bulldozers in tow.

What is now at stake is not just the integrity of a court ruling, but the very idea of legal protection in a constitutional democracy—of the rule of law. If homes can be razed without hearing, if communities can be displaced in the name of regulation, if judgments can be ignored by municipal offices, then the law has already been hollowed out. To break this cycle, compensation is not enough, accountability is essential. Officials who flout court orders must be held liable. Demolitions carried out without due process must not only be condemned but punished, not just by apology or compensation, but by suspensions and prosecutions.

The cost of bulldozer justice must be borne by those who deploy it, not by its victims or the public treasury. Until that happens, the bulldozer will remain more powerful than the Constitution. It will continue to redraw the map of belonging, to erase inconvenient presences, to perform the violence of the state. And the court’s judgment, however well-intentioned, will remain one more paper barrier crushed under the weight of executive will.