How Safdar Ali’s house became a target of guilt by manufactured association

Safdar Ali is 78 years old. His house, built in the 1970s, did not belong to him but to his sons, Syed Qamar Abbas and Syed Faraz Abbas. They had purchased it in 2002 after selling a piece of family land. For over two decades, they never received a single notice from the Prayagraj Development Authority (PDA) about any illegal construction. But on the morning of 2 March 2023, Safdar’s neighbours saw two or three men pasting something on the wall outside the house, click a picture of it, peel it off, and leave. They did not speak to anyone in Safdar’s household about it. No one in his family had time to check what it was. Hours later, their home was gone.

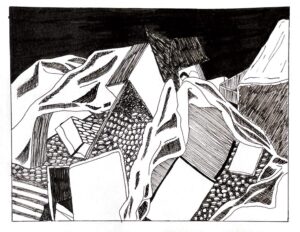

Ali was at his shop in Prayagraj (formerly Allahabad), when he received a call from home. The PDA had arrived, accompanied by a heavy police presence, to demolish his house. He rushed back, finding his neighborhood barricaded, his family standing outside in disbelief, and bulldozers ready to bring down the only Muslim home in the area. They were given no time to vacate. Officials did not present an order. When they kept pressing for an explanation, they were told, “Your construction is illegal.” That was all. The demolition began almost immediately. The PDA workers carried out some belongings, but most of what they owned was swallowed by the rubble. The kitchen, the bedrooms, the cupboards—a structure that Safdar’s family had lived in for decades, reduced to dust within hours.

As arbitrary as the official reason of the demolition—a supposedly illegal construction with no proof or indication of what about it was unlawful—was the unsaid reasoning behind why his house had actually been targeted. Safdar was the only Muslim homeowner in the area, and he knew what that meant. He had been running a licensed gun shop for a long time, but in recent years, whispers began circulating in the neighbour—his name was being linked to the notorious gangster-turned-politician, Atiq Ahmed.

“Media keh rahi hai ki main unko aslahe aur kartoos deta tha, main unka kareebi tha. Kahan se laate hain yeh sab baatein?” (“The media is saying that I supplied weapons and ammunition to him, that I was close to him. How do they even come up with these things?”) Safdar denies having any connection to Atiq Ahmed, except for the distant familiarity that came with Atiq being a public figure. “He was an MP and MLA, I knew him only as much as anyone else did,” he said. “I had no dealings with him.”

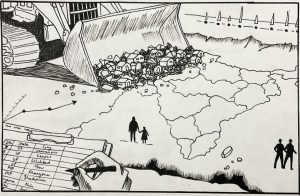

Ever since the Uttar Pradesh chief minister Ajay Singh Bisht began his extrajudicial practice of punitive demolitions, earning him the moniker “Bulldozer Baba,” numerous properties linked to Atiq—or even purported to be linked, with little evidence to support it— have been demolished. It was even declared by Bisht, or Adityanath as he is better known, as an open policy following the murder of Umesh Pal, in February 2023. Umesh was a key witness in a 2005 case concerning the murder of Raju Pal, a member of UP’s state assembly from the Bahujan Samaj Party. Atiq and his brother, Ashraf—both of whom were already in prison at the time—were widely suspected of orchestrating both murders.

In 2004, Atiq became an elected member of parliament for the first time. He vacated his seat in Prayagraj, from where he had been elected successively in the previous five elections, and his brother Ashraf was widely expected to win the seat in the by-poll held in November that year. But in a shock result, Raju defeated Ashraf by 4,000 votes. Atiq and Ashraf were believed to have killed Raju for the affront two months later, and as the case dragged on before the courts, Umesh was said to have been killed as a key witness to the crime. What followed was not a legal investigation but a series of retaliatory demolitions, arrests, and extrajudicial killings, carried out under the guise of swift justice. The case against Atiq Ahmed and his network was built on police allegations, with no formal trial or due process.

Within days of Umesh’s murder, the chief minister Bisht declared on the assembly floor: “Mitti me mila denge”—We will reduce them to dust—signalling what was to come. In the ensuing weeks, bulldozers tore through multiple homes, allegedly belonging to those linked to Atiq Ahmed, without legal orders or hearings. The media played a crucial role in paving the way for these actions—sensationalising the Umesh Pal murder, airing dramatic reconstructions, and turning Atiq Ahmed into the singular face of criminality. News anchors framed demolitions as necessary retribution, bypassing legal scrutiny, while public perception was shaped to see this state-led destruction as justice.

In this climate of manufactured consensus, Safdar Ali’s home became yet another casualty—its demolition justified not by law, and not even by demonstrable association—but by rumours and political convenience. In fact, an Indian Express report from the time of the demolition even quoted a senior police official as stating that they had not found any connections between Safdar and Atiq. The PDA claimed that the proceedings against the house had begun in 2020, Safdar emphasised that his family had received no notice or information about the purported illegality till the time of its demolition.

A few days later, on 16 March 2023, the police raided his shop. Every day from the 2nd to the 16th, Safdar had kept it open, waiting for the officers to come. They found nothing. There was no case against him. But by then, it did not matter. The demolition had already served its purpose. The raid was a mere formality, for appearance’s sake.

Safdar knows his house was demolished because he was Muslim. But he also knows that such targeting does not happen in a vacuum—it is justified, manufactured, and legitimised by the media. “Media bik chuki hai”—The media has sold out—Safdar said. He has seen news channels twist narratives, how reporters turn the demolition of homes into spectacles of supposed justice. “These people are focused on convincing the public that we are wrong, that we are enemies. When the media shows this, people start believing it.”

He knows the pattern. The visuals of the bulldozer, the police, the wreckage—each shot carefully framed, each segment structured to make the audience believe that the destruction was deserved. The media does not ask for evidence. It does not question the absence of due process. It merely reinforces the state’s narrative: that these homes, these people, are illegal. “There are very few who show the truth. The rest are only making the government’s job easier.”

And the government’s job is simple—to punish Muslims in the name of justice, while ensuring that there are no questions, no challenges, and no legal consequences. Even Atiq Ahmed’s own home, rnotwithstanding the state’s hostility towards him, cannot be demolished without legal proceedings and due process. For Muslims, like Safdar Ali, the law does not function as a safeguard. It is a tool that bends to accommodate state’s violence.

Safdar’s sons filed an RTI seeking the demolition order. The PDA did not respond to them. Instead, they wrote to Safdar, stating, “Qamar Abbas wants your house demolition notice.” The reply seemed to suggest that the PDA itself did not know—or did not care—that the house was legally owned by Qamar Abbas and his brother. The family challenged the demolition in the Allahabad High Court. But not a single hearing has taken place. Their petition remains buried under judicial backlog, untouched, unaddressed. “Insaf kya hoga?”— What would justice even look like—Safdar asked. “If we get compensation, if our house is rebuilt, if our map is approved, then maybe that will be some justice. But the mental torture my family went through, there is no way to make up for that.”

With their home reduced to debris, Safdar and his family—his sons, their wives, and their four children—were suddenly homeless. They moved to a relative’s house temporarily, but they couldn’t stay there forever. The search for a rented house was another ordeal, one that many displaced Muslims in Uttar Pradesh have faced. Eventually, they found a place, but it wasn’t home. He remembers one grandchild had asked his father, “Abbu, ab hum log kahan rahenge?”—Abbu, where will we live now?

Safdar’s sense of belonging unravelled. He never settled into the rented house. Every night, he left to sleep at his married daughter’s home instead. It was not just the material loss, it was the stripping away of stability, the forced uprooting, the burden of starting over in his seventies. “Puri grihasti bikhar gayi,”—Our entire household was scarred—he said. Some valuables were stolen, whether by PDA workers during the evacuation or by looters picking through the rubble, he does not know.

Safdar’s voice now carries the exhaustion of a man who has fought for something that should not require a fight. But in this, he was not alone. Unlike many others who find themselves isolated after such demolitions, his relatives stood with him. “Rishtedaar saath khade rahe hamare. Bada itminan tha usse.” (Our relatives stood with us. That gave us great peace.) When asked what message he has for others who have faced demolitions, Safdar responds simply: “Sabr karein. Islam sabr sikhata hai. Sabr bohot zaroori hai.” (Have patience. Islam teaches patience. Patience is very important.)

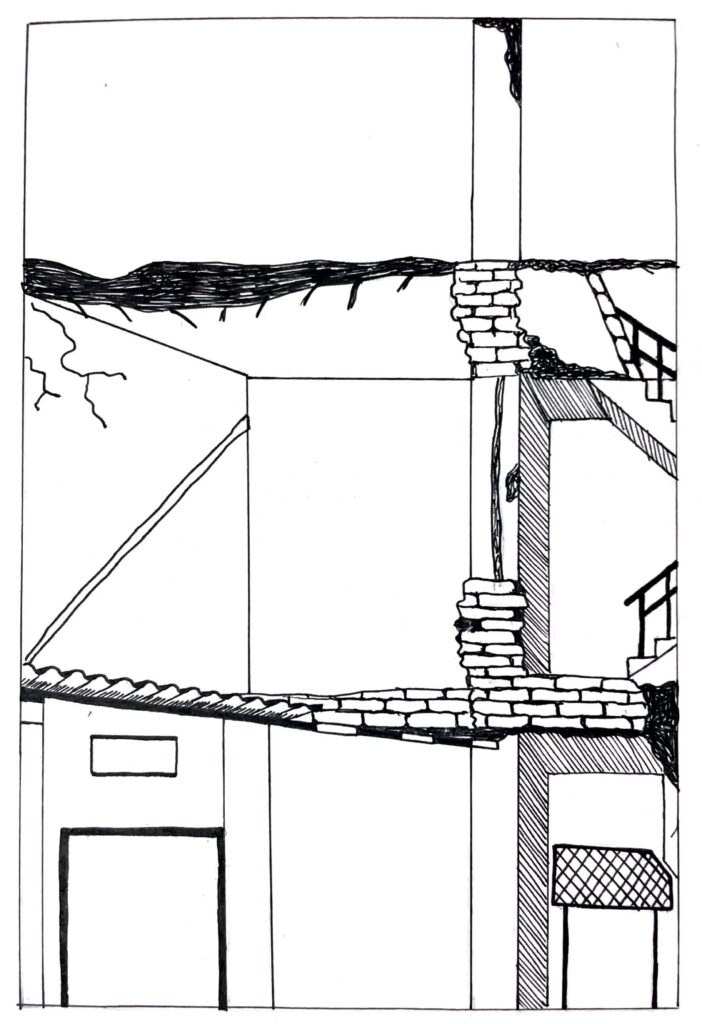

After over a year in displacement, the family made a decision. In July 2024, they returned. They cleared the debris, built temporary walls, and put a shed overhead. Their home was still in ruins, but they could no longer afford to pay rent. And perhaps, despite the broken structure, there was a comfort in being back.

Maybe there is a calm one feels only in their own home. It takes years for a house to become a home, and once it does, it is impossible to leave. Safdar Ali did not leave that home. Maybe he couldn’t. Maybe nobody really can, not unless it’s their own choice to do so—not when it’s forced upon them.

Related Posts

Safdar Ali is 78 years old. His house, built in the 1970s, did not belong to him but to his sons, Syed Qamar Abbas and Syed Faraz Abbas. They had purchased it in 2002 after selling a piece of family land. For over two decades, they never received a single notice from the Prayagraj Development Authority (PDA) about any illegal construction. But on the morning of 2 March 2023, Safdar’s neighbours saw two or three men pasting something on the wall outside the house, click a picture of it, peel it off, and leave. They did not speak to anyone in Safdar’s household about it. No one in his family had time to check what it was. Hours later, their home was gone.

Ali was at his shop in Prayagraj (formerly Allahabad), when he received a call from home. The PDA had arrived, accompanied by a heavy police presence, to demolish his house. He rushed back, finding his neighborhood barricaded, his family standing outside in disbelief, and bulldozers ready to bring down the only Muslim home in the area. They were given no time to vacate. Officials did not present an order. When they kept pressing for an explanation, they were told, “Your construction is illegal.” That was all. The demolition began almost immediately. The PDA workers carried out some belongings, but most of what they owned was swallowed by the rubble. The kitchen, the bedrooms, the cupboards—a structure that Safdar’s family had lived in for decades, reduced to dust within hours.

As arbitrary as the official reason of the demolition—a supposedly illegal construction with no proof or indication of what about it was unlawful—was the unsaid reasoning behind why his house had actually been targeted. Safdar was the only Muslim homeowner in the area, and he knew what that meant. He had been running a licensed gun shop for a long time, but in recent years, whispers began circulating in the neighbour—his name was being linked to the notorious gangster-turned-politician, Atiq Ahmed.

“Media keh rahi hai ki main unko aslahe aur kartoos deta tha, main unka kareebi tha. Kahan se laate hain yeh sab baatein?” (“The media is saying that I supplied weapons and ammunition to him, that I was close to him. How do they even come up with these things?”) Safdar denies having any connection to Atiq Ahmed, except for the distant familiarity that came with Atiq being a public figure. “He was an MP and MLA, I knew him only as much as anyone else did,” he said. “I had no dealings with him.”

Ever since the Uttar Pradesh chief minister Ajay Singh Bisht began his extrajudicial practice of punitive demolitions, earning him the moniker “Bulldozer Baba,” numerous properties linked to Atiq—or even purported to be linked, with little evidence to support it— have been demolished. It was even declared by Bisht, or Adityanath as he is better known, as an open policy following the murder of Umesh Pal, in February 2023. Umesh was a key witness in a 2005 case concerning the murder of Raju Pal, a member of UP’s state assembly from the Bahujan Samaj Party. Atiq and his brother, Ashraf—both of whom were already in prison at the time—were widely suspected of orchestrating both murders.

In 2004, Atiq became an elected member of parliament for the first time. He vacated his seat in Prayagraj, from where he had been elected successively in the previous five elections, and his brother Ashraf was widely expected to win the seat in the by-poll held in November that year. But in a shock result, Raju defeated Ashraf by 4,000 votes. Atiq and Ashraf were believed to have killed Raju for the affront two months later, and as the case dragged on before the courts, Umesh was said to have been killed as a key witness to the crime. What followed was not a legal investigation but a series of retaliatory demolitions, arrests, and extrajudicial killings, carried out under the guise of swift justice. The case against Atiq Ahmed and his network was built on police allegations, with no formal trial or due process.

Within days of Umesh’s murder, the chief minister Bisht declared on the assembly floor: “Mitti me mila denge”—We will reduce them to dust—signalling what was to come. In the ensuing weeks, bulldozers tore through multiple homes, allegedly belonging to those linked to Atiq Ahmed, without legal orders or hearings. The media played a crucial role in paving the way for these actions—sensationalising the Umesh Pal murder, airing dramatic reconstructions, and turning Atiq Ahmed into the singular face of criminality. News anchors framed demolitions as necessary retribution, bypassing legal scrutiny, while public perception was shaped to see this state-led destruction as justice.

In this climate of manufactured consensus, Safdar Ali’s home became yet another casualty—its demolition justified not by law, and not even by demonstrable association—but by rumours and political convenience. In fact, an Indian Express report from the time of the demolition even quoted a senior police official as stating that they had not found any connections between Safdar and Atiq. The PDA claimed that the proceedings against the house had begun in 2020, Safdar emphasised that his family had received no notice or information about the purported illegality till the time of its demolition.

A few days later, on 16 March 2023, the police raided his shop. Every day from the 2nd to the 16th, Safdar had kept it open, waiting for the officers to come. They found nothing. There was no case against him. But by then, it did not matter. The demolition had already served its purpose. The raid was a mere formality, for appearance’s sake.

Safdar knows his house was demolished because he was Muslim. But he also knows that such targeting does not happen in a vacuum—it is justified, manufactured, and legitimised by the media. “Media bik chuki hai”—The media has sold out—Safdar said. He has seen news channels twist narratives, how reporters turn the demolition of homes into spectacles of supposed justice. “These people are focused on convincing the public that we are wrong, that we are enemies. When the media shows this, people start believing it.”

He knows the pattern. The visuals of the bulldozer, the police, the wreckage—each shot carefully framed, each segment structured to make the audience believe that the destruction was deserved. The media does not ask for evidence. It does not question the absence of due process. It merely reinforces the state’s narrative: that these homes, these people, are illegal. “There are very few who show the truth. The rest are only making the government’s job easier.”

And the government’s job is simple—to punish Muslims in the name of justice, while ensuring that there are no questions, no challenges, and no legal consequences. Even Atiq Ahmed’s own home, rnotwithstanding the state’s hostility towards him, cannot be demolished without legal proceedings and due process. For Muslims, like Safdar Ali, the law does not function as a safeguard. It is a tool that bends to accommodate state’s violence.

Safdar’s sons filed an RTI seeking the demolition order. The PDA did not respond to them. Instead, they wrote to Safdar, stating, “Qamar Abbas wants your house demolition notice.” The reply seemed to suggest that the PDA itself did not know—or did not care—that the house was legally owned by Qamar Abbas and his brother. The family challenged the demolition in the Allahabad High Court. But not a single hearing has taken place. Their petition remains buried under judicial backlog, untouched, unaddressed. “Insaf kya hoga?”— What would justice even look like—Safdar asked. “If we get compensation, if our house is rebuilt, if our map is approved, then maybe that will be some justice. But the mental torture my family went through, there is no way to make up for that.”

With their home reduced to debris, Safdar and his family—his sons, their wives, and their four children—were suddenly homeless. They moved to a relative’s house temporarily, but they couldn’t stay there forever. The search for a rented house was another ordeal, one that many displaced Muslims in Uttar Pradesh have faced. Eventually, they found a place, but it wasn’t home. He remembers one grandchild had asked his father, “Abbu, ab hum log kahan rahenge?”—Abbu, where will we live now?

Safdar’s sense of belonging unravelled. He never settled into the rented house. Every night, he left to sleep at his married daughter’s home instead. It was not just the material loss, it was the stripping away of stability, the forced uprooting, the burden of starting over in his seventies. “Puri grihasti bikhar gayi,”—Our entire household was scarred—he said. Some valuables were stolen, whether by PDA workers during the evacuation or by looters picking through the rubble, he does not know.

Safdar’s voice now carries the exhaustion of a man who has fought for something that should not require a fight. But in this, he was not alone. Unlike many others who find themselves isolated after such demolitions, his relatives stood with him. “Rishtedaar saath khade rahe hamare. Bada itminan tha usse.” (Our relatives stood with us. That gave us great peace.) When asked what message he has for others who have faced demolitions, Safdar responds simply: “Sabr karein. Islam sabr sikhata hai. Sabr bohot zaroori hai.” (Have patience. Islam teaches patience. Patience is very important.)

After over a year in displacement, the family made a decision. In July 2024, they returned. They cleared the debris, built temporary walls, and put a shed overhead. Their home was still in ruins, but they could no longer afford to pay rent. And perhaps, despite the broken structure, there was a comfort in being back.

Maybe there is a calm one feels only in their own home. It takes years for a house to become a home, and once it does, it is impossible to leave. Safdar Ali did not leave that home. Maybe he couldn’t. Maybe nobody really can, not unless it’s their own choice to do so—not when it’s forced upon them.

SUPPORT US

We like bringing the stories that don’t get told to you. For that, we need your support. However small, we would appreciate it.