Shrines and mosques in Kashmir are not merely devotional spaces, but complex socio-political sites where the sacred, cultural, and all other dimensions of Kashmiri identity converge. These spaces have been repositories of collective memory that lend a voice to anti-hegemonic aspirations. As a response, perhaps, different regimes have attempted to intervene in these spaces, making deliberate efforts to further cultural erasure and recontextualise them within statist narratives. A deliberate suppression or redefinition of community heritage is a potent tool for state narratives seeking to consolidate power in Kashmir. This was true of the Sikh and Dogra rulers of the past, and remains true of the Indian government today.

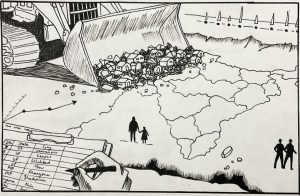

In Kashmir, these sacred spaces face targeted dehistoricisation. The old shrines and mosques, embedded deeply within the Kashmiri identity, are now being recontextualised to fit India’s nationalistic frameworks that disconnect them from their socio-political importance. This dehistoricisation is part of a process where the state appropriates cultural symbols and sites to suppress dissenting voices and impose homogenised narratives. The process aims to transform sacred spaces, including mosques, shrines, and madrassas, into “hollow” entities, severing their links to resistance and redefining them as instruments of state-controlled identity formation.

The processes of dehistoricisation by the state include the securitisation of shrines through military presence and restrictions, their commodification as tourist attractions and film locations, and diminishing of traditional religious authority. “The dehistoricisation of Kashmiri shrines and Kashmir in general is an integral part of the Indian state’s larger agenda of Kashmiri erasure,” observed Dean Accardi, a historian specialising in religion and politics in Kashmir, in an interview to The Polis Project.

The Politics of Sacred Spaces

After the end of the Dogra dynasty’s rule in 1947, Jammu and Kashmir’s controversial accession to India marks a critical juncture in the region’s political trajectory. The Indian state began to extend its control over every dimension of Kashmiri society, including religious places.

As part of a broader strategy to centralise power, this process aimed to strip these spaces of their historical and socio-political significance and reframe local cultural practices within a nationalistic framework, writes Zohra Batool in her research paper, “Religion and the Public Sphere.” She shows how India expanded its pervasive control over political expressions in Kashmir, systematically curtailing dissent through stringent restrictions on protests and public assemblies. Amid the inescapable apparatus of surveillance and constrained public sphere, sacred spaces emerged as sites of collective engagement, where individuals could navigate social and political discourses in the absence of conventional platforms.

Mosque councils and associated committees have played an important role in addressing critical issues affecting everyday life, often stepping in to mitigate the consequences of conflict. These bodies have emerged as vital mechanisms for community mobilisation. They handle matters ranging from legal advocacy to rehabilitation efforts. Shrine and mosque administrative bodies, in both urban and rural settings, have extended their functions to include various social welfare activities, providing essential support in a context marked by systemic disruptions and unmet community needs. For instance, in 2020, a local mosque committee in Srinagar crowdsourced around Rs 3 crore to rebuild civilian houses damaged in an intense gunfight between militants and Indian military forces.

The Kashmir Valley has more than 8,000 mosques and shrines. However, in the urban setting, three in particular—Hazratbal Shrine, Khanqah-i-Maula, and Jamia Masjid—hold pivotal importance in the Valley’s socio-political life. These three sites are critical arenas of faith, political mobilisation, identity, and resistance. Situated on the banks of Dal Lake, Hazratbal has been a site of political engagement for decades, particularly with the National Conference founder Sheikh Abdullah turning it into the ideological nucleus for his party during the Dogra rule and after Kashmir’s accession to India in 1947.

The Hazratbal shrine’s sanctity intertwines with socio-symbolic significance, as was seen during the Moi-e-Muqaddas agitation in 1963. The mass protests that started after the disappearance of the Moi-e-Muqaddas—a relic believed to be the hair of Prophet Muhammad—from the Hazratbal Shrine, ultimately forced the Indian state to act, leading to the relic’s recovery and the fall of the Khawaja Shamsuddin-led government.

Khanqah-i-Maula, one of Kashmir’s oldest and most revered Sufi shrines, has historically played a pivotal role in shaping the region’s spiritual, cultural, and political landscape. Established in the 14th century, the shrine has long functioned as more than just a religious site. In times of political upheaval, Khanqah-i-Maula has emerged as a site of public mobilisation—from anti-colonial movements under Dogra rule to mass prayers and protests in recent decades.

Similarly, the Jamia Masjid occupies a central role in the religious-political consciousness of Kashmir. On July 13, 1931, Jamia Masjid became a focal point for political dissent in Kashmir’s history when 22 Kashmiri Muslims were killed by the Dogra police outside Srinagar’s central jail. The incident, marked as Kashmir Martyrs’ Day, led to significant unrest and mobilisation within the community. The mosque served as a central gathering place for mourners and protesters. Led by the dynamic head imam Mirwaiz Muhammad Yusuf Shah during the Dogra rule, Kashmir’s Grand Mosque eventually turned into a bastion of pro-freedom articulations under the late Mirwaiz Maulvi Farooq and his son Mirwaiz Umar Farooq.

For years after the rise of armed militancy in the Kashmir Valley, the Jamia Masjid remained the centre of political mobilisation. Even up to 2019, congregational prayers on Fridays and other important days were always accompanied by slogans of aazadi (freedom). Having served as conduits between spiritual and worldly lives of Kashmiri Muslims, Hazratbal and the Jamia Masjid exemplify the political potential of sacred spaces. Their domes, symbolic of divine sovereignty, not only inspire devotion but also galvanise collective action, playing an important role around power, resistance, and identity in Kashmir.

Historically, mutawallis (caretakers) managed the Muslim shrines in Kashmir. They were directly accountable to their local communities and community leaders. Traditionally supported by public donations and endowments, this decentralised stewardship characterised the maintenance and construction of these places. As the Dogra rulers began to consolidate power in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, they entangled the religious places in legal and political frameworks. Drawing on colonial models, they sought to regulate local customs, including shrine management, by codifying customary laws. This formalisation had two aims: to institutionalise existing practices and reshape community identity, according to Mridu Rai, the author of the book Hindu Rulers, Muslim Subjects.

The application of customary laws in civil courts consolidated the state’s role in regulating religious practices. Disputes over custodianship became symbolic of broader struggles for power, as different factions sought to assert their authority over these revered spaces. Legal mechanisms, such as the selective dismissal of shrine custodians by the rulers, often served political ends. These transformed the shrines into contested sites of power and political manoeuvring. These legal conflicts facilitated new forms of political mobilisation within the Kashmiri Muslim community, as different factions contested control over sacred spaces.

The institutional framework for managing Muslim endowments took a significant turn in 1940 with the establishment of the Muslim Auqaf Trust. Under Sheikh Abdullah, the trust aimed to manage charitable endowments, support underprivileged communities, and oversee income-generating properties allied to Muslim institutions. This marked a shift from community-based management to a centralised body, which was later reconstituted as the Waqf Board. Shrines also evolved into powerful symbols of religious and political identities. The rise of nationalist movements and demands for Kashmiri Muslim rights further polarised the community, with figures like Abdullah and the Mirwaiz family vying for influence over the sacred sites. These divisions, with the state’s growing involvement in shrine affairs, shaped the fracturing of the Kashmiri Muslim political consciousness.

Securitisations, Dehistoricisation, and Commodification

Following armed insurgency against Indian rule in Kashmir in the late 1980s, shrines and mosques faced heightened state scrutiny, that justified control as necessary to “maintain law and order.” The state cites incidents such as those at Hazratbal and Charar-e-Sharief shrine in the 1990s, where insurgents sought refuge. Indian forces reacted and razed the 600-year-old Charar-e-Sharief to the ground. Most major shrines in Kashmir now have bunkers and are guarded by Indian security forces, symbolising the pervasive militarisation of religious spaces.

Srinagar’s Jamia Masjid has faced systematic closures, particularly on Muslim religious occasions, including Fridays and during Ramadan, highlighting the state’s securitisation policies. Between 2020 and 2021, the mosque remained largely inaccessible; Eid prayers were barred last year for the sixth time since 2019, in a bid to regulate dissent. Official records indicate the mosque remained shut for over 250 days during 2008, 2010, and 2016— the years that saw unrest, highlighting its perceived role as a nucleus of resistance.

Amid the securitisation, “shrine tourism” in Kashmir, promoted by state officials and amplified through Bollywood films, transforms these spaces into sites of consumer-oriented cultural spectacles, dissociated from their historical and political significance. Bollywood’s use of shrines like the Ashmuqam Dargah, stripped of their socio-political context, reinforces this erasure. Popular media presents them as symbols of harmony and spirituality, aligning them with state-led narratives of national integration.

This cinematic portrayal paralleled state policies, bringing the Bollywood increased institutional support for productions in Kashmir, including financial incentives and bureaucratic streamlining. Presenting shrines as mere heritage sites or spiritual retreats overshadows their historical role in community mobilisation and resistance and reiterates a state-sanctioned vision of Kashmir.

This process advances through institutional mechanisms, such as single-window clearance systems for film shoots, which prioritises commercial interests over preserving local heritage. The infusion of celebrity culture, exemplified by Bollywood actors visiting shrines, reframes these historically significant sites as hollow cultural landmarks. Such interventions obscure the shrines’ historic role as loci of spiritual authority and sites of socio-political mobilisation, instead positioning them within a homogenised narrative of Indian secularism and unity.

The Indian state’s intervention in Kashmir’s sacred spaces is also visible in its practice of centralisation and control. The state is increasingly interfering in the administration of Muslim shrines in Kashmir; recently the Jammu and Kashmir’s Waqf Board was reconstituted, with a Bharatiya Janata Party leader appointed as its head. These shrines previously maintained autonomy, but now they fall under a centralised control. This process delegitimised the roles of mutawallis (the caretakers), diminishing their authority and connection to the community.

This bureaucratic justification painting it as an anti-corruption measure, reflects the state’s efforts to curtail the influence of traditional actors who mediated between the spiritual domain and local society, reframing them as instruments of state hegemony. Last year, the head cleric of Hazratbal Shrine was suspended from his duties of leading prayers by the Waqf Board over allegations of forced conversion. Justified as a measure to prevent forced conversions and maintain communal harmony, critics argue it reflects an attack on the autonomy of traditional religious leaders. This also becomes part of a broader pattern of bureaucratic “rationalisation” that seeks to subordinate local spiritual authorities to state oversight.

Citing security concerns, the state has subjected Mirwaiz Umar Farooq, the chairman of Hurriyat Conference, to repeated house arrests and restrictions on delivering sermons at the Jamia Masjid for the last five years. Mirwaiz’s recent sermons, which combine calls for resolution with critiques of government policies affecting Kashmir, reflect the state’s anxieties about religious gatherings’ potential for becoming sites of political mobilisation.

The authorities’ cultural appropriation of Kashmir’s shrine is also common. The Charar-e-Shareef shrine, associated with the 14th-century Sufi saint Sheikh Noor-ud-Din Noorani, became the site of a contentious International Yoga Day event organised by the government. While it was framed as a cultural initiative, some slammed it as an affront to the sanctity of the shrine and its spiritual heritage. The event was seen by many as a deliberate recontextualisation of the region’s sacred spaces into state narratives of integration and “normalcy.”

Accardi, a faculty member at USA’s Connecticut College, commenting on the Indian state’s representation of Kashmiri shrines and culture, called it “a cultural genocide.” He said it accompanies “the ongoing and accelerating political disenfranchisement, social engineering, and violent military occupation of Kashmiris—all serving a majoritarian Indian nationalism that seeks to either eliminate minority and oppressed groups and their discrete cultures, or absorb them into a hegemonic culture of the dominant Indian elite.”

Speaking about government efforts to reshape shrine narratives, Accardi said to The Polis Project that the Indian government consistently attempts to reframe Kashmiri shrine histories into two main narratives: firstly, Sufi figures and their shrines are portrayed as examples of anti-communalism and early secularism, depicting Sufis as apolitical and spiritual figures. Secondly, they are characterised as foreign invaders who aggressively oppressed Hindus and built shrines over Hindu temples. “Both narratives serve the Hindu nationalist agenda because they frame Kashmiri Muslims as either hostile foreigners who don’t belong and thus should leave or be eliminated, or they are ‘not real Muslims’ and thus should revert back to their ‘native religion’ of Hinduism or accept their status as second-class citizens subservient to the Hindu majority.”

This dual narrative, as Accardi highlights, plays a significant role in aligning the histories of Kashmiri shrines with nationalistic ideologies. These reinterpretations not only delegitimise Kashmiri Muslims’ cultural and religious heritage, but shape how the region’s history is perceived within the framework of Indian nationalism. The state’s intervention in sacred spaces not only altered their administrative structures but also the communal consciousness and everyday religious practices. The growing centralisation of shrine administration, coupled with securitization and commodification, has disrupted the organic relationship between these spaces and the communities that sustain them. This has led to increasing disillusionment with religious institutions that were once central to local governance and resistance.

The recent measures by the Jammu and Kashmir Waqf Board, such as restrictions on donation collections, control over Friday sermons, and censorship of political issues in religious spaces, have sparked significant public backlash. Political parties, religious leaders, and grassroot communities perceive these actions as direct interference in religious freedoms and an attempt to restructure the sacred spaces of Kashmir in line with state narratives.

Religious leaders, including Mirwaiz Umar Farooq, have been vocal in condemning state-imposed controls over religious institutions. He denounced the requirement for mutawalis to seek permission from state-appointed Waqf officials before delivering Friday sermons, calling it an attack on the religious rights of Kashmiri Muslims. Farooq further criticised the BJP-led government’s Waqf Amendment Bill as an attempt to centralise religious authority and strip local religious leaders of their autonomy.

Beyond protests and political opposition, Kashmiri society has responded through active resistance to state-imposed religious discourse. The public rejection of a delegation of Sufi clerics from mainland India, seen as a government-sponsored attempt to promote a specific religious identity, illustrates this. The visiting clerics, dressed in saffron robes, were met with anti-government slogans at the Hazratbal shrine.

The censorship of political themes in religious sermons, including discussions about Palestine, further illustrates the extent of state intervention. Preachers allege the Waqf Board restricts mention of Palestine to prevent anti-Israel protests. These responses underline a broader sentiment of resistance within Kashmiri society. While the state seeks to neutralise the political potency of sacred spaces, these interventions have, in many ways, reinforced public determination to safeguard their religious and cultural autonomy.

Related Posts

Shrines and mosques in Kashmir are not merely devotional spaces, but complex socio-political sites where the sacred, cultural, and all other dimensions of Kashmiri identity converge. These spaces have been repositories of collective memory that lend a voice to anti-hegemonic aspirations. As a response, perhaps, different regimes have attempted to intervene in these spaces, making deliberate efforts to further cultural erasure and recontextualise them within statist narratives. A deliberate suppression or redefinition of community heritage is a potent tool for state narratives seeking to consolidate power in Kashmir. This was true of the Sikh and Dogra rulers of the past, and remains true of the Indian government today.

In Kashmir, these sacred spaces face targeted dehistoricisation. The old shrines and mosques, embedded deeply within the Kashmiri identity, are now being recontextualised to fit India’s nationalistic frameworks that disconnect them from their socio-political importance. This dehistoricisation is part of a process where the state appropriates cultural symbols and sites to suppress dissenting voices and impose homogenised narratives. The process aims to transform sacred spaces, including mosques, shrines, and madrassas, into “hollow” entities, severing their links to resistance and redefining them as instruments of state-controlled identity formation.

The processes of dehistoricisation by the state include the securitisation of shrines through military presence and restrictions, their commodification as tourist attractions and film locations, and diminishing of traditional religious authority. “The dehistoricisation of Kashmiri shrines and Kashmir in general is an integral part of the Indian state’s larger agenda of Kashmiri erasure,” observed Dean Accardi, a historian specialising in religion and politics in Kashmir, in an interview to The Polis Project.

The Politics of Sacred Spaces

After the end of the Dogra dynasty’s rule in 1947, Jammu and Kashmir’s controversial accession to India marks a critical juncture in the region’s political trajectory. The Indian state began to extend its control over every dimension of Kashmiri society, including religious places.

As part of a broader strategy to centralise power, this process aimed to strip these spaces of their historical and socio-political significance and reframe local cultural practices within a nationalistic framework, writes Zohra Batool in her research paper, “Religion and the Public Sphere.” She shows how India expanded its pervasive control over political expressions in Kashmir, systematically curtailing dissent through stringent restrictions on protests and public assemblies. Amid the inescapable apparatus of surveillance and constrained public sphere, sacred spaces emerged as sites of collective engagement, where individuals could navigate social and political discourses in the absence of conventional platforms.

Mosque councils and associated committees have played an important role in addressing critical issues affecting everyday life, often stepping in to mitigate the consequences of conflict. These bodies have emerged as vital mechanisms for community mobilisation. They handle matters ranging from legal advocacy to rehabilitation efforts. Shrine and mosque administrative bodies, in both urban and rural settings, have extended their functions to include various social welfare activities, providing essential support in a context marked by systemic disruptions and unmet community needs. For instance, in 2020, a local mosque committee in Srinagar crowdsourced around Rs 3 crore to rebuild civilian houses damaged in an intense gunfight between militants and Indian military forces.

The Kashmir Valley has more than 8,000 mosques and shrines. However, in the urban setting, three in particular—Hazratbal Shrine, Khanqah-i-Maula, and Jamia Masjid—hold pivotal importance in the Valley’s socio-political life. These three sites are critical arenas of faith, political mobilisation, identity, and resistance. Situated on the banks of Dal Lake, Hazratbal has been a site of political engagement for decades, particularly with the National Conference founder Sheikh Abdullah turning it into the ideological nucleus for his party during the Dogra rule and after Kashmir’s accession to India in 1947.

The Hazratbal shrine’s sanctity intertwines with socio-symbolic significance, as was seen during the Moi-e-Muqaddas agitation in 1963. The mass protests that started after the disappearance of the Moi-e-Muqaddas—a relic believed to be the hair of Prophet Muhammad—from the Hazratbal Shrine, ultimately forced the Indian state to act, leading to the relic’s recovery and the fall of the Khawaja Shamsuddin-led government.

Khanqah-i-Maula, one of Kashmir’s oldest and most revered Sufi shrines, has historically played a pivotal role in shaping the region’s spiritual, cultural, and political landscape. Established in the 14th century, the shrine has long functioned as more than just a religious site. In times of political upheaval, Khanqah-i-Maula has emerged as a site of public mobilisation—from anti-colonial movements under Dogra rule to mass prayers and protests in recent decades.

Similarly, the Jamia Masjid occupies a central role in the religious-political consciousness of Kashmir. On July 13, 1931, Jamia Masjid became a focal point for political dissent in Kashmir’s history when 22 Kashmiri Muslims were killed by the Dogra police outside Srinagar’s central jail. The incident, marked as Kashmir Martyrs’ Day, led to significant unrest and mobilisation within the community. The mosque served as a central gathering place for mourners and protesters. Led by the dynamic head imam Mirwaiz Muhammad Yusuf Shah during the Dogra rule, Kashmir’s Grand Mosque eventually turned into a bastion of pro-freedom articulations under the late Mirwaiz Maulvi Farooq and his son Mirwaiz Umar Farooq.

For years after the rise of armed militancy in the Kashmir Valley, the Jamia Masjid remained the centre of political mobilisation. Even up to 2019, congregational prayers on Fridays and other important days were always accompanied by slogans of aazadi (freedom). Having served as conduits between spiritual and worldly lives of Kashmiri Muslims, Hazratbal and the Jamia Masjid exemplify the political potential of sacred spaces. Their domes, symbolic of divine sovereignty, not only inspire devotion but also galvanise collective action, playing an important role around power, resistance, and identity in Kashmir.

Historically, mutawallis (caretakers) managed the Muslim shrines in Kashmir. They were directly accountable to their local communities and community leaders. Traditionally supported by public donations and endowments, this decentralised stewardship characterised the maintenance and construction of these places. As the Dogra rulers began to consolidate power in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, they entangled the religious places in legal and political frameworks. Drawing on colonial models, they sought to regulate local customs, including shrine management, by codifying customary laws. This formalisation had two aims: to institutionalise existing practices and reshape community identity, according to Mridu Rai, the author of the book Hindu Rulers, Muslim Subjects.

The application of customary laws in civil courts consolidated the state’s role in regulating religious practices. Disputes over custodianship became symbolic of broader struggles for power, as different factions sought to assert their authority over these revered spaces. Legal mechanisms, such as the selective dismissal of shrine custodians by the rulers, often served political ends. These transformed the shrines into contested sites of power and political manoeuvring. These legal conflicts facilitated new forms of political mobilisation within the Kashmiri Muslim community, as different factions contested control over sacred spaces.

The institutional framework for managing Muslim endowments took a significant turn in 1940 with the establishment of the Muslim Auqaf Trust. Under Sheikh Abdullah, the trust aimed to manage charitable endowments, support underprivileged communities, and oversee income-generating properties allied to Muslim institutions. This marked a shift from community-based management to a centralised body, which was later reconstituted as the Waqf Board. Shrines also evolved into powerful symbols of religious and political identities. The rise of nationalist movements and demands for Kashmiri Muslim rights further polarised the community, with figures like Abdullah and the Mirwaiz family vying for influence over the sacred sites. These divisions, with the state’s growing involvement in shrine affairs, shaped the fracturing of the Kashmiri Muslim political consciousness.

Securitisations, Dehistoricisation, and Commodification

Following armed insurgency against Indian rule in Kashmir in the late 1980s, shrines and mosques faced heightened state scrutiny, that justified control as necessary to “maintain law and order.” The state cites incidents such as those at Hazratbal and Charar-e-Sharief shrine in the 1990s, where insurgents sought refuge. Indian forces reacted and razed the 600-year-old Charar-e-Sharief to the ground. Most major shrines in Kashmir now have bunkers and are guarded by Indian security forces, symbolising the pervasive militarisation of religious spaces.

Srinagar’s Jamia Masjid has faced systematic closures, particularly on Muslim religious occasions, including Fridays and during Ramadan, highlighting the state’s securitisation policies. Between 2020 and 2021, the mosque remained largely inaccessible; Eid prayers were barred last year for the sixth time since 2019, in a bid to regulate dissent. Official records indicate the mosque remained shut for over 250 days during 2008, 2010, and 2016— the years that saw unrest, highlighting its perceived role as a nucleus of resistance.

Amid the securitisation, “shrine tourism” in Kashmir, promoted by state officials and amplified through Bollywood films, transforms these spaces into sites of consumer-oriented cultural spectacles, dissociated from their historical and political significance. Bollywood’s use of shrines like the Ashmuqam Dargah, stripped of their socio-political context, reinforces this erasure. Popular media presents them as symbols of harmony and spirituality, aligning them with state-led narratives of national integration.

This cinematic portrayal paralleled state policies, bringing the Bollywood increased institutional support for productions in Kashmir, including financial incentives and bureaucratic streamlining. Presenting shrines as mere heritage sites or spiritual retreats overshadows their historical role in community mobilisation and resistance and reiterates a state-sanctioned vision of Kashmir.

This process advances through institutional mechanisms, such as single-window clearance systems for film shoots, which prioritises commercial interests over preserving local heritage. The infusion of celebrity culture, exemplified by Bollywood actors visiting shrines, reframes these historically significant sites as hollow cultural landmarks. Such interventions obscure the shrines’ historic role as loci of spiritual authority and sites of socio-political mobilisation, instead positioning them within a homogenised narrative of Indian secularism and unity.

The Indian state’s intervention in Kashmir’s sacred spaces is also visible in its practice of centralisation and control. The state is increasingly interfering in the administration of Muslim shrines in Kashmir; recently the Jammu and Kashmir’s Waqf Board was reconstituted, with a Bharatiya Janata Party leader appointed as its head. These shrines previously maintained autonomy, but now they fall under a centralised control. This process delegitimised the roles of mutawallis (the caretakers), diminishing their authority and connection to the community.

This bureaucratic justification painting it as an anti-corruption measure, reflects the state’s efforts to curtail the influence of traditional actors who mediated between the spiritual domain and local society, reframing them as instruments of state hegemony. Last year, the head cleric of Hazratbal Shrine was suspended from his duties of leading prayers by the Waqf Board over allegations of forced conversion. Justified as a measure to prevent forced conversions and maintain communal harmony, critics argue it reflects an attack on the autonomy of traditional religious leaders. This also becomes part of a broader pattern of bureaucratic “rationalisation” that seeks to subordinate local spiritual authorities to state oversight.

Citing security concerns, the state has subjected Mirwaiz Umar Farooq, the chairman of Hurriyat Conference, to repeated house arrests and restrictions on delivering sermons at the Jamia Masjid for the last five years. Mirwaiz’s recent sermons, which combine calls for resolution with critiques of government policies affecting Kashmir, reflect the state’s anxieties about religious gatherings’ potential for becoming sites of political mobilisation.

The authorities’ cultural appropriation of Kashmir’s shrine is also common. The Charar-e-Shareef shrine, associated with the 14th-century Sufi saint Sheikh Noor-ud-Din Noorani, became the site of a contentious International Yoga Day event organised by the government. While it was framed as a cultural initiative, some slammed it as an affront to the sanctity of the shrine and its spiritual heritage. The event was seen by many as a deliberate recontextualisation of the region’s sacred spaces into state narratives of integration and “normalcy.”

Accardi, a faculty member at USA’s Connecticut College, commenting on the Indian state’s representation of Kashmiri shrines and culture, called it “a cultural genocide.” He said it accompanies “the ongoing and accelerating political disenfranchisement, social engineering, and violent military occupation of Kashmiris—all serving a majoritarian Indian nationalism that seeks to either eliminate minority and oppressed groups and their discrete cultures, or absorb them into a hegemonic culture of the dominant Indian elite.”

Speaking about government efforts to reshape shrine narratives, Accardi said to The Polis Project that the Indian government consistently attempts to reframe Kashmiri shrine histories into two main narratives: firstly, Sufi figures and their shrines are portrayed as examples of anti-communalism and early secularism, depicting Sufis as apolitical and spiritual figures. Secondly, they are characterised as foreign invaders who aggressively oppressed Hindus and built shrines over Hindu temples. “Both narratives serve the Hindu nationalist agenda because they frame Kashmiri Muslims as either hostile foreigners who don’t belong and thus should leave or be eliminated, or they are ‘not real Muslims’ and thus should revert back to their ‘native religion’ of Hinduism or accept their status as second-class citizens subservient to the Hindu majority.”

This dual narrative, as Accardi highlights, plays a significant role in aligning the histories of Kashmiri shrines with nationalistic ideologies. These reinterpretations not only delegitimise Kashmiri Muslims’ cultural and religious heritage, but shape how the region’s history is perceived within the framework of Indian nationalism. The state’s intervention in sacred spaces not only altered their administrative structures but also the communal consciousness and everyday religious practices. The growing centralisation of shrine administration, coupled with securitization and commodification, has disrupted the organic relationship between these spaces and the communities that sustain them. This has led to increasing disillusionment with religious institutions that were once central to local governance and resistance.

The recent measures by the Jammu and Kashmir Waqf Board, such as restrictions on donation collections, control over Friday sermons, and censorship of political issues in religious spaces, have sparked significant public backlash. Political parties, religious leaders, and grassroot communities perceive these actions as direct interference in religious freedoms and an attempt to restructure the sacred spaces of Kashmir in line with state narratives.

Religious leaders, including Mirwaiz Umar Farooq, have been vocal in condemning state-imposed controls over religious institutions. He denounced the requirement for mutawalis to seek permission from state-appointed Waqf officials before delivering Friday sermons, calling it an attack on the religious rights of Kashmiri Muslims. Farooq further criticised the BJP-led government’s Waqf Amendment Bill as an attempt to centralise religious authority and strip local religious leaders of their autonomy.

Beyond protests and political opposition, Kashmiri society has responded through active resistance to state-imposed religious discourse. The public rejection of a delegation of Sufi clerics from mainland India, seen as a government-sponsored attempt to promote a specific religious identity, illustrates this. The visiting clerics, dressed in saffron robes, were met with anti-government slogans at the Hazratbal shrine.

The censorship of political themes in religious sermons, including discussions about Palestine, further illustrates the extent of state intervention. Preachers allege the Waqf Board restricts mention of Palestine to prevent anti-Israel protests. These responses underline a broader sentiment of resistance within Kashmiri society. While the state seeks to neutralise the political potency of sacred spaces, these interventions have, in many ways, reinforced public determination to safeguard their religious and cultural autonomy.

SUPPORT US

We like bringing the stories that don’t get told to you. For that, we need your support. However small, we would appreciate it.