How BJP’s narrative on Jharkhand’s tribal population decline obfuscates a complex reality

In the din of the Bharatiya Janata Party’s unsuccessful Jharkhand electoral campaign, marked by the incessant rhetoric of Bangladeshi infiltration and tribal population decline, there lies a deep and complex reality. There is no evidence of any illegal Bangladeshi migrants in the Santhal Pargana region. Moreover, the claims around the tribal decline overlook the myriad socio-economic pressures of industrialisation, land alienation, poverty and marginalisation that have driven indigenous populations to the brink of dispossession. The rise in migration and the dwindling presence of tribals are less about religious encroachment and more about the slow suffocation of an entire way of life under the weight of economic forces. This is not a simple story of “us” versus “them,” but one of exploitation, survival, and an ever-changing struggle for identity amidst a backdrop of political and economic forces larger than any single community or narrative.

In 2022, a writ petition to the Jharkhand High Court, reportedly filed by a local BJP worker, claimed that illegal immigration from Bangladesh and forced religious conversions of tribals were altering the demographic fabric of the Santhal Pargana region. While it is unsurprising that the BJP has weaponised the judicial proceedings to sow fear and accuse Muslim immigrants of exerting undue influence over tribal populations, the court’s role in fomenting this narrative raises cause for concern. Without subjecting the claims of illegal Bangadeshi immigrants to any scrutiny, this August, the bench of Sujit Narayan Prasad and Arun Kumar Rai impleaded the Border Security Force, the Intelligence Bureau and the National Investigation Agency, among others, as parties to the case.

Even after the deputy commissioners of the Santhal Pargana region’s six districts—namely, Godda, Jamtara, Pakur, Dumka, Sahibganj and Deoghar—all filed affidavits stating that there was no record of any supposed Bangladeshi infiltration, the bench did not relent. Only Sahibganj reported the presence of just two illegal Bangladeshi immigrants over the last two years. Yet, the court disputed the state’s claims without citing any evidence in support, merely noting that the decline in the tribal population in the region from 44.67% in 1951 to 28.11% 2011, according to census reports, “reflects otherwise.” Moreover, when the state government submitted that any alleged infiltration would happen through West Bengal and other border regions, which would require a coordinated effort by the states and the centre, the court interpreted it as an admission of Bangladeshi infiltration. After making all these observations, the court directed the centre and the state to constitute a fact-finding committee to look into the issue.

Meanwhile, the narrative has already been conclusively rejected by multiple media reports as well as a comprehensive fact-finding inquiry jointly conducted by the civil-society collectives Jharkhand Janadhikar Mahasabha and Loktantra Bachao Abhiyan. The fact-finding report, based on interviews with local villagers, community leaders, and activists, asserts that the Bengali-speaking Muslims identified as illegal immigrants are in fact long-time residents of the region. They noted that across Santhal Pargana’s villages, not a single person they spoke to reported having any information about any Bangladeshi immigrants, though they had all seen the claims circulate on social media. It clarified that the majority of the Muslim population in Santhal Pargana are from the Shershabadia community, who have been settled in the region for decades, whereas the others, such as the Pasmanda Muslims, are from neighbouring states.

Ashok Verma, a Jharkhand-based activist and journalist who has carefully researched migratory patterns in Pakur area, claims the same. After investigating perhaps 10-15 new Muslim bastis within a five-kilometre radius of Pakur and contacting their families, he discovered no evidence of illegal immigrants. These families even provided the 1932 census documents as proof that they are natives of the region who have relocated from more rural areas for employment.

Crucially, the fact-finding report also highlighted the anti-Muslim hate speech and fear-mongering by the BJP in its selective representation of facts. The BJP and the high court petition focused on the decline in tribal population between 1951 and 2011, and the increase in Muslim population from 9.44% to 22.73% during the same period. In doing so, it presented the situation as Muslims changing the demography of Jharkhand, which included completely false claims of Bangladeshi Muslims forcibly marrying Adivasi women to claim their land. But the fact-finding report pointed out that according to census data, in the period from 1951 to 2011, “the Hindu population increased by 24 lakh, the Muslim population by 13.6 lakh, and the Adivasi population by 8.7 lakh.”

The report concluded that “it is clear that the data presented by the BJP in Parliament and the media are false.” However, it also noted that the “declining proportion of Adivasis in the total population is a serious issue, and there is a need to understand its root causes.” Indeed, the discussion surrounding the issues of the decline in the tribal population needs to be placed within the broader framework of a low birth-rate due to poor nutrition and healthcare in the region; the non-implementation of the Santhal Pargana Tenancy Act that protects the alienation of Adivasis from their land; and the economic hardships and out-migration associated with industrialisation and historical exploitation.

Nandita Bhattacharya, a member of the recent fact-finding team, stated that the BJP has politicised the entire issue for its own gain. She emphasised that while Jharkhand shares a border with West Bengal, and many people in the state speak Bengali, this does not imply they are Bangladeshi. According to her, the controversy being stirred up is fundamentally an attack on women and their autonomy over their bodies and choices. “Issues like the Uniform Civil Code (UCC) and ‘love jihad’ are designed to control a woman’s right to choose her own partner,” Bhattacharya said.

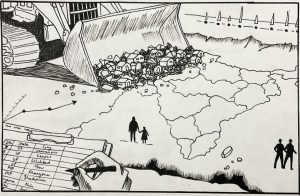

Bhattacharya also argued that this politicisation is part of a strategy by the BJP to replicate the unrest seen in Manipur within Jharkhand. This, she suggested, would ultimately enable the state and corporations to take control of the mineral-rich tribal lands. When asked why six specific districts are being targeted, she explained that these are areas where the BJP failed to secure an electoral majority. The numbers support the claim: in the last state elections, the BJP won just two of the 28 seats reserved for the Scheduled Tribes, down from 11 in 2014. In the Santhal Pargana region, it won just four seats in 2019, in Deoghar, Godda, Rajmahal, and Mandu. In the Lok Sabha elections this year, the BJP lost all five tribal seats, but won in the general category Godda seat in the Santhal Pargana region.

The infiltration narrative found no takers, with the BJP winning just one of the 18 assembly seats in the Santhal Pargana region, and its vote share dipping in six of them. Meanwhile the Jharkhand Mukti Morcha maintained its stronghold in the region, winning 11 seats, while the Congress won four seats and the Rashtriya Janata Dal claimed two seats.

The Broader Picture: Migration, Industrialisation, and Economic Pressures

It is crucial to recognise the broader economic and historical forces that have shaped the demographic trends in Jharkhand. The region has witnessed significant changes in its population dynamics due to a combination of factors: the migration of non-tribals into the region, the out-migration of tribals to other regions for work, industrialisation, displacement due to development projects, and land alienation.

Between 1881 and 1951, the non-tribal population, particularly from north Bihar, Odisha, West Bengal, and other regions, grew due to immigration driven by industrialisation and urbanisation. In his study, “Jharkhand Tribals: Are they Really A Minority?” the researcher Alexius Ekka states that in 1891, about 60% of immigrants to Manbhum—one of the districts of East India under the British Raj, that subsequently became a part of Bihar, and now lies in present-day Jharkhand—were from Odisha, West Bengal, and Madhya Pradesh. The share of north Bihar migrants to the region increased from 10% in 1881 to 40% in 1951. The migration of labourers for mining and industrial work in regions like Dhanbad and Jamshedpur also contributed to this demographic shift. Parallel to the immigration, tribals also emigrated, especially for work in tea gardens, with Ekka writing that around 33,000 tribals migrated to Assam and Bengal in 1891, which increased to 947,000 by 1921. According to Ekka, in the post-independence period from 1951-1995, planned development projects such as dams, industries, and mines displaced around 30 lakh people, with 90% of them being tribals. However, only 25% of these displaced people were rehabilitated.

The decline of the tribal population has also been exacerbated by malnutrition. Muffazar Hussain, an activist from the Pakur district of Santhal Pargana who is associated with the Right to Food and Right to Work movements, added that the region suffers from poor healthcare, and does not have primary health centres, hospitals, or Anganwadis.

Ashok Verma, another activist in the region, observed that local schools in the region have a lopsided student-teacher ratio, and that the money allotted by the government for mid-day lunches and student uniforms is being eaten up by systemic corruption. “One of the key causes of tribal population decrease is the double impact of starvation and poverty,” Verma said. “It has increased death rates, with tribals being more likely to die young, between the ages of 40 and 50. These malnourished tribes have even lower reproduction rates, which is also contributing to their diminishing numbers.”

Further, in this study, Ekka states that the tribal population believes they are not recognised as a majority due to the Indian government’s refusal to acknowledge indigenous communities. He mentions that the numbers of tribals are underestimated in census data, pointing out that if groups like the Kurmis—who form a populace of 44 lakh in Jharkhand and are listed among the Other Backward Classes—were included in the tribal population, the Scheduled Tribes would surpass 60% of the state’s total population.

The census also fails to properly account for tribals who follow traditional religions, such as the indigenous Sarna faith centred around nature worship; it groups them under the category of “Others,” leading to a misrepresentation of their actual numbers. Scholars suggest that tribals should be identified according to their traditional faith and ethnic origins to more accurately reflect their demographic presence in Jharkhand. Hussain, too, noted that the courts and state cannot reduce the Adivasi question to a question of a rising Muslim population, given that so many are wrongfully not counted as Adivasis. “Santhal Pargana has Hansda, Murmu, Soren and Marandi, but in the census their enumeration isn’t done on the basis of their ethnic identity,” he added.

Research has shown unemployment, education, agricultural productivity and climate-related factors to be among the main reasons for tribal migration out of Jharkhand. A 2012 study by Prakash Chandra Deogharia, Migration From Remote Tribal Villages Of Jharkhand: An Evidence From South Chotanagpur, examined migration patterns in six villages from three districts in Jharkhand’s South Chotanagpur region, which has a majority tribal population. It found that seasonal migration is a significant coping mechanism, with households migrating for about 13 to 18 man-months—referring to the work one person can do in a month‑per year. On average, 2.3 members from each household migrate, primarily due to food insecurity and agricultural instability. Shocks like harvest failure, depletion of livestock, increased debts, and the resulting need for loans further intensify the migration process.

Verma and Hussain noted how the same patterns are reflected in Santhal Pargana as well. The region’s Adivasis hold small plots of land, but due to a lack of agricultural and irrigation equipment that they cannot afford, they are unable to earn a living off of it. In the absence of any state support through irrigation, agriculture has substantially reduced in the area. This forces them to sell their land illegally to non-tribals and seek alternative jobs, pushing them to relocate to other neighbouring districts such as Bardhaman in West Bengal, primarily on a seasonal basis. These tribes only return for 15-20 days every few months, and usually go back during rice harvesting season for crop cutting. While women, too, migrate to urban spaces, the main migration of Adivasis is for crop cutting.

A 2000 research paper by Shubhra Shailee titled, “Tribal Identity In Jharkhand Region: Issues Of Industrial Displacement And Jharkhand Movement,” shows how industrial development and displacement have also historically contributed to the decline in the tribal population in Jharkhand. Before 1950, most large dams displaced non-tribal populations in other regions, but after independence, many dams and industrial projects were established in tribal areas. For example, 22 out of 58 dams between 30.1 and 50 metres were built in tribal areas, displacing large numbers of tribal people. This displacement, combined with the exploitation of natural resources, has led to the impoverishment of the indigenous tribal population, while immigrants employed in development projects have improved their socio-economic status, further marginalising the tribals in the region.

Mathew Areeparampil discusses this issue in his 1995 book, Tribals of Jharkhand: Victims of Development, revealing the significant displacement of indigenous populations due to the establishment of large-scale industrial projects. The study notes that the Uranium Corporation of India Ltd took over five villages in Jaduguda, in East Singhbhum, displacing 2,047 people, nearly half of whom were tribals, mainly Santhals, without proper resettlement or compensation. Similarly, the Tata Iron and Steel Company (established in Singhbhum in 1907) had initially acquired 3,564 acres of land by displacing people from four villages ‑ Sakchi, Nutandi, Susnidih and the northern part of Jugsalai in Singhbhum district, resulting in the near disappearance of the indigenous population. By 1981, 58% of TISCO’s 36,554 permanent employees were from Bihar, with 71.14% of tribal employees in unskilled positions.

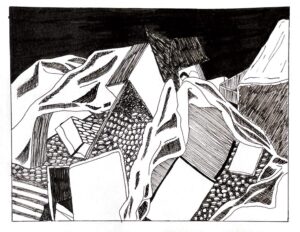

Santhal Pargana is rich with minerals like coal and limestone, and similarly vulnerable for industrial projects. For instance, Verma noted that when the Adani Group set up the Godda thermal power plant in 2016–17, the project took over the land of around 40-50 families by displacing them, and bulldozed their farm land, which was about to yield rice crops in a month.

Understanding population trends

Authors such as SY Quraishi, Nilakantan RS, and Utsa Patnaik challenge prevailing narratives about demographic changes in India. In their respective books, they present data that highlights the role of socio-economic conditions, regional divides, and international economic policies in shaping population trends and resource availability.

In The Population Myth, Quraishi, a former Chief Election Commissioner of India, confronts the common belief that population growth is largely influenced by religious affiliations. He examines data from the First Planning Commission to the 2011 Census, arguing that economic mobility and access to education are stronger determinants of population growth than religion. According to National Family Health Survey (NFHS) data, between 2005 and 2016, the Muslim population in India experienced a relative decrease, while the Hindu population increased. Fertility rates for both communities fell in this period, with a more significant reduction among Muslims (23%) compared to Hindus (18%). These findings underscore Quraishi’s argument that education and economic opportunity exert a greater influence on fertility and population growth than religious background.

Similarly, in South vs North: India’s Great Divide, Nilakantan RS explores how regional economic disparities within India shape population trends. South Indian states such as Kerala, Tamil Nadu, Telangana, Karnataka, and Andhra Pradesh have low Total Fertility Rates (TFRs) of 1.6–1.7, indicative of socioeconomic development, while North Indian states, including Bihar, Uttar Pradesh, Rajasthan, and Madhya Pradesh, exhibit higher TFRs ranging from 2.2 to 3.2. Projections for 2031-2041 further illustrate this divide, with Tamil Nadu expected to experience a population decline, and stability in Andhra Pradesh. Conversely, Uttar Pradesh, Rajasthan, Bihar, and Jharkhand are anticipated to experience population growth with growth rates of 0.7, 0.8, 1, and 0.8, respectively. This regional comparison supports the argument that economic development, not religion or cultural differences, is central to population and demographic changes.

In her essays, “The Ideology of Overpopulation” and “The Costs of Free Trade,” Utsa Patnaik critiques the global narrative around overpopulation, asserting that it obscures the deeper issues of historical exploitation and structural inequality. Patnaik contends that the concept of “overpopulation” often serves as an ideological tool, shifting the blame for poverty and resource scarcity onto high birth rates in countries like India. She argues that this view ignores the impact of colonialism, which plundered resources from India and other colonies, and disregards the ongoing economic pressures created by neoliberal policies pushed by developed nations.

Patnaik emphasises that Western frameworks wrongly attribute the economic challenges in developing nations to local population growth rather than acknowledging the legacy of colonial exploitation and the present-day global economic policies that perpetuate inequality. For instance, while high birth rates are commonly cited as a reason for poverty and food insecurity, Patnaik argues that these issues are more accurately linked to global resource disparities and the manipulation of agricultural and trade policies by wealthy nations.

She further critiques the effects of international trade agreements on India’s economy, particularly following the neoliberal reforms of the 1990s. Rural livelihoods became less sustainable due to the decline in agricultural support and public services as a consequence of these policies, leading to a surge in migration to urban centers. For Patnaik, this migration reflects not only a demographic shift but also a symptom of the economic exploitation perpetuated by global trade agreements. Rural populations, particularly small-scale farmers and agricultural labourers, are pushed into unstable urban labour markets where job security is low and economic vulnerability is high.

The demographic shifts in Santhal Pargana are a result of several intersecting factors—economic, historical, and political—not just the simplistic narratives of illegal immigration and conversion. While migration, industrialisation, and land alienation have certainly contributed to the changing demographics of the region, it is essential to focus on the structural inequalities that have made tribal populations vulnerable. These issues cannot be understood in isolation but must be situated within the larger context of socio-economic forces that shape the lives of India’s tribal communities.

Related Posts

How BJP’s narrative on Jharkhand’s tribal population decline obfuscates a complex reality

In the din of the Bharatiya Janata Party’s unsuccessful Jharkhand electoral campaign, marked by the incessant rhetoric of Bangladeshi infiltration and tribal population decline, there lies a deep and complex reality. There is no evidence of any illegal Bangladeshi migrants in the Santhal Pargana region. Moreover, the claims around the tribal decline overlook the myriad socio-economic pressures of industrialisation, land alienation, poverty and marginalisation that have driven indigenous populations to the brink of dispossession. The rise in migration and the dwindling presence of tribals are less about religious encroachment and more about the slow suffocation of an entire way of life under the weight of economic forces. This is not a simple story of “us” versus “them,” but one of exploitation, survival, and an ever-changing struggle for identity amidst a backdrop of political and economic forces larger than any single community or narrative.

In 2022, a writ petition to the Jharkhand High Court, reportedly filed by a local BJP worker, claimed that illegal immigration from Bangladesh and forced religious conversions of tribals were altering the demographic fabric of the Santhal Pargana region. While it is unsurprising that the BJP has weaponised the judicial proceedings to sow fear and accuse Muslim immigrants of exerting undue influence over tribal populations, the court’s role in fomenting this narrative raises cause for concern. Without subjecting the claims of illegal Bangadeshi immigrants to any scrutiny, this August, the bench of Sujit Narayan Prasad and Arun Kumar Rai impleaded the Border Security Force, the Intelligence Bureau and the National Investigation Agency, among others, as parties to the case.

Even after the deputy commissioners of the Santhal Pargana region’s six districts—namely, Godda, Jamtara, Pakur, Dumka, Sahibganj and Deoghar—all filed affidavits stating that there was no record of any supposed Bangladeshi infiltration, the bench did not relent. Only Sahibganj reported the presence of just two illegal Bangladeshi immigrants over the last two years. Yet, the court disputed the state’s claims without citing any evidence in support, merely noting that the decline in the tribal population in the region from 44.67% in 1951 to 28.11% 2011, according to census reports, “reflects otherwise.” Moreover, when the state government submitted that any alleged infiltration would happen through West Bengal and other border regions, which would require a coordinated effort by the states and the centre, the court interpreted it as an admission of Bangladeshi infiltration. After making all these observations, the court directed the centre and the state to constitute a fact-finding committee to look into the issue.

Meanwhile, the narrative has already been conclusively rejected by multiple media reports as well as a comprehensive fact-finding inquiry jointly conducted by the civil-society collectives Jharkhand Janadhikar Mahasabha and Loktantra Bachao Abhiyan. The fact-finding report, based on interviews with local villagers, community leaders, and activists, asserts that the Bengali-speaking Muslims identified as illegal immigrants are in fact long-time residents of the region. They noted that across Santhal Pargana’s villages, not a single person they spoke to reported having any information about any Bangladeshi immigrants, though they had all seen the claims circulate on social media. It clarified that the majority of the Muslim population in Santhal Pargana are from the Shershabadia community, who have been settled in the region for decades, whereas the others, such as the Pasmanda Muslims, are from neighbouring states.

Ashok Verma, a Jharkhand-based activist and journalist who has carefully researched migratory patterns in Pakur area, claims the same. After investigating perhaps 10-15 new Muslim bastis within a five-kilometre radius of Pakur and contacting their families, he discovered no evidence of illegal immigrants. These families even provided the 1932 census documents as proof that they are natives of the region who have relocated from more rural areas for employment.

Crucially, the fact-finding report also highlighted the anti-Muslim hate speech and fear-mongering by the BJP in its selective representation of facts. The BJP and the high court petition focused on the decline in tribal population between 1951 and 2011, and the increase in Muslim population from 9.44% to 22.73% during the same period. In doing so, it presented the situation as Muslims changing the demography of Jharkhand, which included completely false claims of Bangladeshi Muslims forcibly marrying Adivasi women to claim their land. But the fact-finding report pointed out that according to census data, in the period from 1951 to 2011, “the Hindu population increased by 24 lakh, the Muslim population by 13.6 lakh, and the Adivasi population by 8.7 lakh.”

The report concluded that “it is clear that the data presented by the BJP in Parliament and the media are false.” However, it also noted that the “declining proportion of Adivasis in the total population is a serious issue, and there is a need to understand its root causes.” Indeed, the discussion surrounding the issues of the decline in the tribal population needs to be placed within the broader framework of a low birth-rate due to poor nutrition and healthcare in the region; the non-implementation of the Santhal Pargana Tenancy Act that protects the alienation of Adivasis from their land; and the economic hardships and out-migration associated with industrialisation and historical exploitation.

Nandita Bhattacharya, a member of the recent fact-finding team, stated that the BJP has politicised the entire issue for its own gain. She emphasised that while Jharkhand shares a border with West Bengal, and many people in the state speak Bengali, this does not imply they are Bangladeshi. According to her, the controversy being stirred up is fundamentally an attack on women and their autonomy over their bodies and choices. “Issues like the Uniform Civil Code (UCC) and ‘love jihad’ are designed to control a woman’s right to choose her own partner,” Bhattacharya said.

Bhattacharya also argued that this politicisation is part of a strategy by the BJP to replicate the unrest seen in Manipur within Jharkhand. This, she suggested, would ultimately enable the state and corporations to take control of the mineral-rich tribal lands. When asked why six specific districts are being targeted, she explained that these are areas where the BJP failed to secure an electoral majority. The numbers support the claim: in the last state elections, the BJP won just two of the 28 seats reserved for the Scheduled Tribes, down from 11 in 2014. In the Santhal Pargana region, it won just four seats in 2019, in Deoghar, Godda, Rajmahal, and Mandu. In the Lok Sabha elections this year, the BJP lost all five tribal seats, but won in the general category Godda seat in the Santhal Pargana region.

The infiltration narrative found no takers, with the BJP winning just one of the 18 assembly seats in the Santhal Pargana region, and its vote share dipping in six of them. Meanwhile the Jharkhand Mukti Morcha maintained its stronghold in the region, winning 11 seats, while the Congress won four seats and the Rashtriya Janata Dal claimed two seats.

The Broader Picture: Migration, Industrialisation, and Economic Pressures

It is crucial to recognise the broader economic and historical forces that have shaped the demographic trends in Jharkhand. The region has witnessed significant changes in its population dynamics due to a combination of factors: the migration of non-tribals into the region, the out-migration of tribals to other regions for work, industrialisation, displacement due to development projects, and land alienation.

Between 1881 and 1951, the non-tribal population, particularly from north Bihar, Odisha, West Bengal, and other regions, grew due to immigration driven by industrialisation and urbanisation. In his study, “Jharkhand Tribals: Are they Really A Minority?” the researcher Alexius Ekka states that in 1891, about 60% of immigrants to Manbhum—one of the districts of East India under the British Raj, that subsequently became a part of Bihar, and now lies in present-day Jharkhand—were from Odisha, West Bengal, and Madhya Pradesh. The share of north Bihar migrants to the region increased from 10% in 1881 to 40% in 1951. The migration of labourers for mining and industrial work in regions like Dhanbad and Jamshedpur also contributed to this demographic shift. Parallel to the immigration, tribals also emigrated, especially for work in tea gardens, with Ekka writing that around 33,000 tribals migrated to Assam and Bengal in 1891, which increased to 947,000 by 1921. According to Ekka, in the post-independence period from 1951-1995, planned development projects such as dams, industries, and mines displaced around 30 lakh people, with 90% of them being tribals. However, only 25% of these displaced people were rehabilitated.

The decline of the tribal population has also been exacerbated by malnutrition. Muffazar Hussain, an activist from the Pakur district of Santhal Pargana who is associated with the Right to Food and Right to Work movements, added that the region suffers from poor healthcare, and does not have primary health centres, hospitals, or Anganwadis.

Ashok Verma, another activist in the region, observed that local schools in the region have a lopsided student-teacher ratio, and that the money allotted by the government for mid-day lunches and student uniforms is being eaten up by systemic corruption. “One of the key causes of tribal population decrease is the double impact of starvation and poverty,” Verma said. “It has increased death rates, with tribals being more likely to die young, between the ages of 40 and 50. These malnourished tribes have even lower reproduction rates, which is also contributing to their diminishing numbers.”

Further, in this study, Ekka states that the tribal population believes they are not recognised as a majority due to the Indian government’s refusal to acknowledge indigenous communities. He mentions that the numbers of tribals are underestimated in census data, pointing out that if groups like the Kurmis—who form a populace of 44 lakh in Jharkhand and are listed among the Other Backward Classes—were included in the tribal population, the Scheduled Tribes would surpass 60% of the state’s total population.

The census also fails to properly account for tribals who follow traditional religions, such as the indigenous Sarna faith centred around nature worship; it groups them under the category of “Others,” leading to a misrepresentation of their actual numbers. Scholars suggest that tribals should be identified according to their traditional faith and ethnic origins to more accurately reflect their demographic presence in Jharkhand. Hussain, too, noted that the courts and state cannot reduce the Adivasi question to a question of a rising Muslim population, given that so many are wrongfully not counted as Adivasis. “Santhal Pargana has Hansda, Murmu, Soren and Marandi, but in the census their enumeration isn’t done on the basis of their ethnic identity,” he added.

Research has shown unemployment, education, agricultural productivity and climate-related factors to be among the main reasons for tribal migration out of Jharkhand. A 2012 study by Prakash Chandra Deogharia, Migration From Remote Tribal Villages Of Jharkhand: An Evidence From South Chotanagpur, examined migration patterns in six villages from three districts in Jharkhand’s South Chotanagpur region, which has a majority tribal population. It found that seasonal migration is a significant coping mechanism, with households migrating for about 13 to 18 man-months—referring to the work one person can do in a month‑per year. On average, 2.3 members from each household migrate, primarily due to food insecurity and agricultural instability. Shocks like harvest failure, depletion of livestock, increased debts, and the resulting need for loans further intensify the migration process.

Verma and Hussain noted how the same patterns are reflected in Santhal Pargana as well. The region’s Adivasis hold small plots of land, but due to a lack of agricultural and irrigation equipment that they cannot afford, they are unable to earn a living off of it. In the absence of any state support through irrigation, agriculture has substantially reduced in the area. This forces them to sell their land illegally to non-tribals and seek alternative jobs, pushing them to relocate to other neighbouring districts such as Bardhaman in West Bengal, primarily on a seasonal basis. These tribes only return for 15-20 days every few months, and usually go back during rice harvesting season for crop cutting. While women, too, migrate to urban spaces, the main migration of Adivasis is for crop cutting.

A 2000 research paper by Shubhra Shailee titled, “Tribal Identity In Jharkhand Region: Issues Of Industrial Displacement And Jharkhand Movement,” shows how industrial development and displacement have also historically contributed to the decline in the tribal population in Jharkhand. Before 1950, most large dams displaced non-tribal populations in other regions, but after independence, many dams and industrial projects were established in tribal areas. For example, 22 out of 58 dams between 30.1 and 50 metres were built in tribal areas, displacing large numbers of tribal people. This displacement, combined with the exploitation of natural resources, has led to the impoverishment of the indigenous tribal population, while immigrants employed in development projects have improved their socio-economic status, further marginalising the tribals in the region.

Mathew Areeparampil discusses this issue in his 1995 book, Tribals of Jharkhand: Victims of Development, revealing the significant displacement of indigenous populations due to the establishment of large-scale industrial projects. The study notes that the Uranium Corporation of India Ltd took over five villages in Jaduguda, in East Singhbhum, displacing 2,047 people, nearly half of whom were tribals, mainly Santhals, without proper resettlement or compensation. Similarly, the Tata Iron and Steel Company (established in Singhbhum in 1907) had initially acquired 3,564 acres of land by displacing people from four villages ‑ Sakchi, Nutandi, Susnidih and the northern part of Jugsalai in Singhbhum district, resulting in the near disappearance of the indigenous population. By 1981, 58% of TISCO’s 36,554 permanent employees were from Bihar, with 71.14% of tribal employees in unskilled positions.

Santhal Pargana is rich with minerals like coal and limestone, and similarly vulnerable for industrial projects. For instance, Verma noted that when the Adani Group set up the Godda thermal power plant in 2016–17, the project took over the land of around 40-50 families by displacing them, and bulldozed their farm land, which was about to yield rice crops in a month.

Understanding population trends

Authors such as SY Quraishi, Nilakantan RS, and Utsa Patnaik challenge prevailing narratives about demographic changes in India. In their respective books, they present data that highlights the role of socio-economic conditions, regional divides, and international economic policies in shaping population trends and resource availability.

In The Population Myth, Quraishi, a former Chief Election Commissioner of India, confronts the common belief that population growth is largely influenced by religious affiliations. He examines data from the First Planning Commission to the 2011 Census, arguing that economic mobility and access to education are stronger determinants of population growth than religion. According to National Family Health Survey (NFHS) data, between 2005 and 2016, the Muslim population in India experienced a relative decrease, while the Hindu population increased. Fertility rates for both communities fell in this period, with a more significant reduction among Muslims (23%) compared to Hindus (18%). These findings underscore Quraishi’s argument that education and economic opportunity exert a greater influence on fertility and population growth than religious background.

Similarly, in South vs North: India’s Great Divide, Nilakantan RS explores how regional economic disparities within India shape population trends. South Indian states such as Kerala, Tamil Nadu, Telangana, Karnataka, and Andhra Pradesh have low Total Fertility Rates (TFRs) of 1.6–1.7, indicative of socioeconomic development, while North Indian states, including Bihar, Uttar Pradesh, Rajasthan, and Madhya Pradesh, exhibit higher TFRs ranging from 2.2 to 3.2. Projections for 2031-2041 further illustrate this divide, with Tamil Nadu expected to experience a population decline, and stability in Andhra Pradesh. Conversely, Uttar Pradesh, Rajasthan, Bihar, and Jharkhand are anticipated to experience population growth with growth rates of 0.7, 0.8, 1, and 0.8, respectively. This regional comparison supports the argument that economic development, not religion or cultural differences, is central to population and demographic changes.

In her essays, “The Ideology of Overpopulation” and “The Costs of Free Trade,” Utsa Patnaik critiques the global narrative around overpopulation, asserting that it obscures the deeper issues of historical exploitation and structural inequality. Patnaik contends that the concept of “overpopulation” often serves as an ideological tool, shifting the blame for poverty and resource scarcity onto high birth rates in countries like India. She argues that this view ignores the impact of colonialism, which plundered resources from India and other colonies, and disregards the ongoing economic pressures created by neoliberal policies pushed by developed nations.

Patnaik emphasises that Western frameworks wrongly attribute the economic challenges in developing nations to local population growth rather than acknowledging the legacy of colonial exploitation and the present-day global economic policies that perpetuate inequality. For instance, while high birth rates are commonly cited as a reason for poverty and food insecurity, Patnaik argues that these issues are more accurately linked to global resource disparities and the manipulation of agricultural and trade policies by wealthy nations.

She further critiques the effects of international trade agreements on India’s economy, particularly following the neoliberal reforms of the 1990s. Rural livelihoods became less sustainable due to the decline in agricultural support and public services as a consequence of these policies, leading to a surge in migration to urban centers. For Patnaik, this migration reflects not only a demographic shift but also a symptom of the economic exploitation perpetuated by global trade agreements. Rural populations, particularly small-scale farmers and agricultural labourers, are pushed into unstable urban labour markets where job security is low and economic vulnerability is high.

The demographic shifts in Santhal Pargana are a result of several intersecting factors—economic, historical, and political—not just the simplistic narratives of illegal immigration and conversion. While migration, industrialisation, and land alienation have certainly contributed to the changing demographics of the region, it is essential to focus on the structural inequalities that have made tribal populations vulnerable. These issues cannot be understood in isolation but must be situated within the larger context of socio-economic forces that shape the lives of India’s tribal communities.

SUPPORT US

We like bringing the stories that don’t get told to you. For that, we need your support. However small, we would appreciate it.