Why the erasure of sociopolitical realities in SC’s demolitions judgment is its undoing

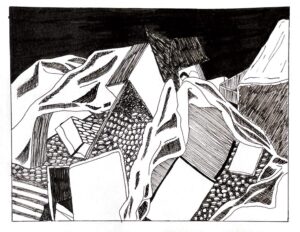

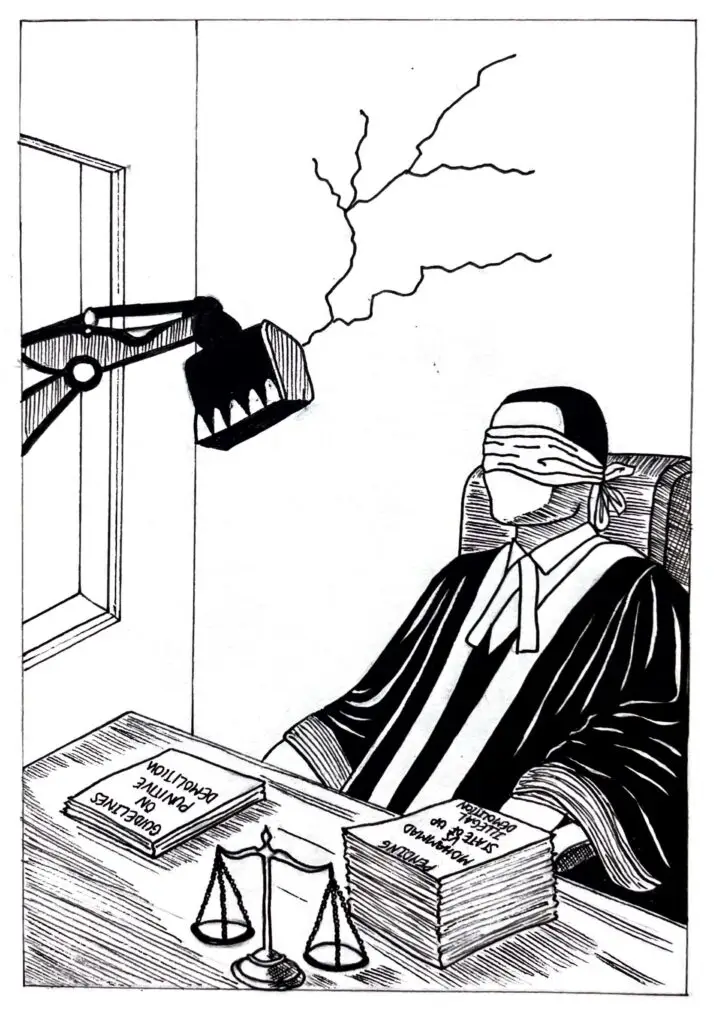

Last November, the Supreme Court delivered a widely-hailed verdict on the illegality of punitive, extrajudicial demolitions in India—but one that still left much to be desired in both scope and implementation. In its verdict, the court discussed the inviolability of rule of law, separation of powers, and public accountability in Indian jurisprudence, declaring that the practice of demolitions falls foul of each of them. It denounced demolitions as unconstitutional collective punishment that is akin to “anarchy,” and ruled that such state excesses must be “dealt with the heavy hand of the law.” Yet, for all its judicial righteousness, the judgment ignores, or avoids, the socio-political reality within which demolitions operate. In doing so, it leaves its enforceability in question, at best.

The bench of justices BR Gavai and KV Viswanathan condemned the practice of “bulldozer justice” that has increasingly become part of the political discourse in India, particularly in Uttar Pradesh and Madhya Pradesh. Notably, both states were represented in court by the solicitor general, Tushar Mehta. The judgment emphasised that the executive cannot act as a judge and take punitive measures without following due process.

To address this, the court introduced guidelines mandating a notice period, judicial oversight, and accountability for officials. Acknowledging the practice of backdated notices being provided after a demolition, the court also directed the establishment of a digital portal to ensure transparency in the demolition process. The verdict even proposes financial penalties and contempt proceedings for officials violating the law. Despite these, several states have already violated the guidelines by proceeding with demolitions without adhering to the newly established due process.

But implementing these measures will prove challenging in a system rife with impunity. The guidelines reveal significant lacunae that undermine their impact, especially when viewed against the backdrop of demolitions emerging as a tool for state-sanctioned violence that targets marginalised communities, particularly Muslims. Even when acknowledging that demolitions may be extrajudicial, the court did so by noting that homes or other structures belonging to individuals accused of crimes are targeted while the surrounding ones are untouched. However, it ignored that the accusations themselves are usually falsely imposed in response to peaceful protests, and in many cases, are entirely baseless.

On its procedural guidelines, too, the Supreme Court falls short of recognising ground realities. For instance, the court’s guidelines mandate that no demolition shall be conducted without a show cause notice provided at least 15-days prior, or in accordance with local municipal laws, whichever is later. Even municipal laws in Uttar Pradesh mandate a 30-day notice period, and the court missed an opportunity to make that the nationwide minimum. A 30-day period, while still limited, at least offers a more realistic window for affected individuals to mobilise legal aid and financial resources, and gather basic information about the demolition proceedings.

Similarly, the court mandates only a 15-day period after the final demolition order and its execution. The guidelines specify that this period is for the owner or occupier of the house to remove the unauthorised construction or appeal against the order. But once again, the Supreme Court assumed that affected individuals will be able to challenge the demolition orders within the 15-day period, ignoring the deep inequalities in access to legal resources.

The guidelines further mandate the creation of a digital portal for uploading notices, hearings, and reports. However, digital transparency does not automatically translate into enforceability. Who will monitor this portal? Will affected individuals have the right to dispute false reports uploaded to the system? Will there be independent audits to ensure the information is not manipulated? Without proper oversight, the digital portal could become a mere bureaucratic exercise—one that legitimises demolitions without providing real protections.

The judgment does not identify these details, and the states are yet to issue any rules or notifications regarding them. In fact, the court had mandated municipal authorities to set up these portals within three months of the order—a deadline that lapsed on February 12 this year. The worst offenders of punitive demolitions—Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, Assam, and Haryana—are all yet to set up the portals.

The guidelines mandate that every individual should be given a personal hearing, and that a detailed report must be prepared by the concerned authority before any demolition. But effectively, it entrusts municipal officials and police personnel, the very authorities that are complicit in illegal demolitions, with the responsibility of overseeing its due process requirements. This is a major conflict of interest. Municipal authorities have often carried out demolitions at the behest of political directives, and police officers have been seen facilitating, supervising, and even executing demolitions, rather than acting as neutral enforcers of the law.

Expecting these entities to act as impartial adjudicators is unrealistic and creates scope for subversion of the guidelines. If the same municipal officers who issue demolition orders are also the ones conducting personal hearings and compiling reports, it creates a self-regulated system where violations can be covered up or justified post-facto. A better approach would have been to mandate independent review boards or judicial officers to preside over hearings and oversee documentation, ensuring that decisions are not driven by political or communal biases.

This approach would have also ensured that municipal authorities are required to justify any proposed demolition to an independent authority before it can be executed, rather than placing the onus on individuals targeted by the state to challenge the proceedings. The affected individuals, most often from marginalised communities, are expected to navigate a complex, expensive, and time-consuming legal process within a mere 15-day window—an expectation that ignores the systemic barriers to legal recourse.

The guidelines introduce a provision for holding officials personally accountable for illegal demolitions, including financial penalties and contempt proceedings. While this appears to be a step toward accountability, its implementation will depend almost entirely on the judiciary’s ability and intent to hold such officials personally responsible, given the entrenched culture of bureaucratic and political impunity. Municipal officials and police personnel who execute demolition orders often do so under political pressure, and as such, the state authorities are likely not going to direct its officials to pay compensation for carrying out orders that were instructed to them by the same authorities.

The court’s failure to recognise, or acknowledge, the political support for demolitions is also reflected in the absence of any superior command responsibility in its guidelines concerning accountability. The guidelines operate under the mistaken underlying assumption that the buck stops with municipal authorities, instead of tracing it up the political ladder to its source. The absence of any directive to investigate higher-level complicity, such as orders issued by chief ministers or senior bureaucrats, means that accountability will likely be restricted to lower-level functionaries, protecting those who wield real power.

Moreover, the idea that officials will personally bear financial liability ignores the reality of administrative shielding, wherein the state routinely absorbs legal costs on behalf of its functionaries. A more effective approach would have mandated the creation of an independent oversight body to review past and future demolitions, ensuring that decisions are free from communal bias and political influence. Additionally, victims of unlawful demolitions should have been provided with a direct legal route to claim compensation from the state. Without such measures, the promise of accountability remains painfully hollow.

The judgment also steers clear of any discussion of retrospective justice for the many victims of extrajudicial, punitive demolitions in India over recent years. It identifies no mechanism for restitution, no compensation for victims, and no accountability from the officials who ordered previous unlawful demolitions. This selective concern for procedural integrity in future cases while ignoring past state violence reinforces the pattern of impunity that has emboldened municipal authorities and law enforcement agencies to continue such actions under the guise of governance.

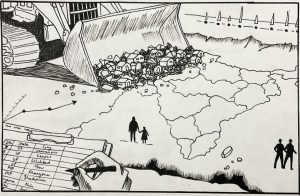

Perhaps most crucially, the bench of Gavai and Viswanathan shy away from addressing the fact that demolitions in India are politically motivated acts of collective punishment that disproportionately target Muslim communities. The pattern is well-documented: in instances of political protests or communal tensions, Muslim homes and businesses are demolished under the pretext of “illegal encroachment” or “unauthorized constructions” while similar acts by other communities remain unaddressed. Reports from human rights organizations, independent journalists, and legal advocacy groups have repeatedly shown that these demolitions are not random enforcement measures but strategic acts of retribution, aimed at dismantling Muslim homes, businesses, and community structures under the pretext of illegality.

The court’s silence on this pattern of targeting Muslim communities effectively legitimises selective state violence by refusing to name those who bear the brunt of it. This omission is not incidental; it reflects a broader judicial hesitance to confront the reality of state-orchestrated anti-Muslim violence. The judiciary has long relied on legal formalism to sidestep the political nature of such state actions, thereby allowing communal targeting to persist under the veil of legal neutrality. This erasure is particularly appalling given that punitive demolitions have been widely documented as a tactic used against Indian Muslims following instances of political dissent or protests against state policies. By refusing to name the affected community, the verdict not only whitewashes the state’s communal bias but also renders the suffering of Muslim families invisible within the nation’s legal discourse. This deliberate omission allows the state to continue its actions while claiming legal legitimacy, reducing demolitions to procedural matters rather than acts of systemic violence.

The enforceability of the Supreme Court’s guidelines on punitive demolitions remains deeply uncertain, much like the fate of the Tehseen Poonawalla judgment of 2018 on mob violence, which laid the foundation for curbing hate crimes but failed to translate into effective action on the ground. Despite the clear directives, lynchings and communal violence have continued with impunity, exposing the glaring gap between judicial pronouncements and executive enforcement. The same risk looms over the demolition guidelines.

Another serious concern over the guidelines’ enforceability is the continued demolitions despite the court’s directives. The recent contempt notice issued to Uttar Pradesh authorities for demolishing part of the Madni Mosque in Khushinagar in violation of the court’s order is a striking example. The incident highlights how state authorities continue to act with impunity—raising serious questions about the judiciary’s ability to check such excesses and ensure compliance.

While the Supreme Court’s verdict introduces certain procedural barriers against punitive demolitions, it does not dismantle the structural conditions that allow these demolitions to function as tools of state violence. The verdict, framed as a corrective measure, ultimately functions as a judicial compromise that protects the state from deeper scrutiny. The lack of independent oversight, the entrusting of key responsibilities to biased municipal and police officials, and the absence of clear penalties for non-compliance mean that these measures are likely to be circumvented in practice.

Without clear protections against communal targeting, retrospective justice for past victims, or a legal framework that prioritizes judicial oversight over executive discretion, the verdict serves more as an adjustment than an intervention against state violence. The absence of a clear stance on anti-Muslim targeting signals to the state that as long as legal formalities are observed, the political project of marginalisation can continue unimpeded. If justice is to be meaningful, it must go beyond procedural safeguards and dismantle the very conditions that allow violence to masquerade as governance.

Related Posts

Why the erasure of sociopolitical realities in SC’s demolitions judgment is its undoing

Last November, the Supreme Court delivered a widely-hailed verdict on the illegality of punitive, extrajudicial demolitions in India—but one that still left much to be desired in both scope and implementation. In its verdict, the court discussed the inviolability of rule of law, separation of powers, and public accountability in Indian jurisprudence, declaring that the practice of demolitions falls foul of each of them. It denounced demolitions as unconstitutional collective punishment that is akin to “anarchy,” and ruled that such state excesses must be “dealt with the heavy hand of the law.” Yet, for all its judicial righteousness, the judgment ignores, or avoids, the socio-political reality within which demolitions operate. In doing so, it leaves its enforceability in question, at best.

The bench of justices BR Gavai and KV Viswanathan condemned the practice of “bulldozer justice” that has increasingly become part of the political discourse in India, particularly in Uttar Pradesh and Madhya Pradesh. Notably, both states were represented in court by the solicitor general, Tushar Mehta. The judgment emphasised that the executive cannot act as a judge and take punitive measures without following due process.

To address this, the court introduced guidelines mandating a notice period, judicial oversight, and accountability for officials. Acknowledging the practice of backdated notices being provided after a demolition, the court also directed the establishment of a digital portal to ensure transparency in the demolition process. The verdict even proposes financial penalties and contempt proceedings for officials violating the law. Despite these, several states have already violated the guidelines by proceeding with demolitions without adhering to the newly established due process.

But implementing these measures will prove challenging in a system rife with impunity. The guidelines reveal significant lacunae that undermine their impact, especially when viewed against the backdrop of demolitions emerging as a tool for state-sanctioned violence that targets marginalised communities, particularly Muslims. Even when acknowledging that demolitions may be extrajudicial, the court did so by noting that homes or other structures belonging to individuals accused of crimes are targeted while the surrounding ones are untouched. However, it ignored that the accusations themselves are usually falsely imposed in response to peaceful protests, and in many cases, are entirely baseless.

On its procedural guidelines, too, the Supreme Court falls short of recognising ground realities. For instance, the court’s guidelines mandate that no demolition shall be conducted without a show cause notice provided at least 15-days prior, or in accordance with local municipal laws, whichever is later. Even municipal laws in Uttar Pradesh mandate a 30-day notice period, and the court missed an opportunity to make that the nationwide minimum. A 30-day period, while still limited, at least offers a more realistic window for affected individuals to mobilise legal aid and financial resources, and gather basic information about the demolition proceedings.

Similarly, the court mandates only a 15-day period after the final demolition order and its execution. The guidelines specify that this period is for the owner or occupier of the house to remove the unauthorised construction or appeal against the order. But once again, the Supreme Court assumed that affected individuals will be able to challenge the demolition orders within the 15-day period, ignoring the deep inequalities in access to legal resources.

The guidelines further mandate the creation of a digital portal for uploading notices, hearings, and reports. However, digital transparency does not automatically translate into enforceability. Who will monitor this portal? Will affected individuals have the right to dispute false reports uploaded to the system? Will there be independent audits to ensure the information is not manipulated? Without proper oversight, the digital portal could become a mere bureaucratic exercise—one that legitimises demolitions without providing real protections.

The judgment does not identify these details, and the states are yet to issue any rules or notifications regarding them. In fact, the court had mandated municipal authorities to set up these portals within three months of the order—a deadline that lapsed on February 12 this year. The worst offenders of punitive demolitions—Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, Assam, and Haryana—are all yet to set up the portals.

The guidelines mandate that every individual should be given a personal hearing, and that a detailed report must be prepared by the concerned authority before any demolition. But effectively, it entrusts municipal officials and police personnel, the very authorities that are complicit in illegal demolitions, with the responsibility of overseeing its due process requirements. This is a major conflict of interest. Municipal authorities have often carried out demolitions at the behest of political directives, and police officers have been seen facilitating, supervising, and even executing demolitions, rather than acting as neutral enforcers of the law.

Expecting these entities to act as impartial adjudicators is unrealistic and creates scope for subversion of the guidelines. If the same municipal officers who issue demolition orders are also the ones conducting personal hearings and compiling reports, it creates a self-regulated system where violations can be covered up or justified post-facto. A better approach would have been to mandate independent review boards or judicial officers to preside over hearings and oversee documentation, ensuring that decisions are not driven by political or communal biases.

This approach would have also ensured that municipal authorities are required to justify any proposed demolition to an independent authority before it can be executed, rather than placing the onus on individuals targeted by the state to challenge the proceedings. The affected individuals, most often from marginalised communities, are expected to navigate a complex, expensive, and time-consuming legal process within a mere 15-day window—an expectation that ignores the systemic barriers to legal recourse.

The guidelines introduce a provision for holding officials personally accountable for illegal demolitions, including financial penalties and contempt proceedings. While this appears to be a step toward accountability, its implementation will depend almost entirely on the judiciary’s ability and intent to hold such officials personally responsible, given the entrenched culture of bureaucratic and political impunity. Municipal officials and police personnel who execute demolition orders often do so under political pressure, and as such, the state authorities are likely not going to direct its officials to pay compensation for carrying out orders that were instructed to them by the same authorities.

The court’s failure to recognise, or acknowledge, the political support for demolitions is also reflected in the absence of any superior command responsibility in its guidelines concerning accountability. The guidelines operate under the mistaken underlying assumption that the buck stops with municipal authorities, instead of tracing it up the political ladder to its source. The absence of any directive to investigate higher-level complicity, such as orders issued by chief ministers or senior bureaucrats, means that accountability will likely be restricted to lower-level functionaries, protecting those who wield real power.

Moreover, the idea that officials will personally bear financial liability ignores the reality of administrative shielding, wherein the state routinely absorbs legal costs on behalf of its functionaries. A more effective approach would have mandated the creation of an independent oversight body to review past and future demolitions, ensuring that decisions are free from communal bias and political influence. Additionally, victims of unlawful demolitions should have been provided with a direct legal route to claim compensation from the state. Without such measures, the promise of accountability remains painfully hollow.

The judgment also steers clear of any discussion of retrospective justice for the many victims of extrajudicial, punitive demolitions in India over recent years. It identifies no mechanism for restitution, no compensation for victims, and no accountability from the officials who ordered previous unlawful demolitions. This selective concern for procedural integrity in future cases while ignoring past state violence reinforces the pattern of impunity that has emboldened municipal authorities and law enforcement agencies to continue such actions under the guise of governance.

Perhaps most crucially, the bench of Gavai and Viswanathan shy away from addressing the fact that demolitions in India are politically motivated acts of collective punishment that disproportionately target Muslim communities. The pattern is well-documented: in instances of political protests or communal tensions, Muslim homes and businesses are demolished under the pretext of “illegal encroachment” or “unauthorized constructions” while similar acts by other communities remain unaddressed. Reports from human rights organizations, independent journalists, and legal advocacy groups have repeatedly shown that these demolitions are not random enforcement measures but strategic acts of retribution, aimed at dismantling Muslim homes, businesses, and community structures under the pretext of illegality.

The court’s silence on this pattern of targeting Muslim communities effectively legitimises selective state violence by refusing to name those who bear the brunt of it. This omission is not incidental; it reflects a broader judicial hesitance to confront the reality of state-orchestrated anti-Muslim violence. The judiciary has long relied on legal formalism to sidestep the political nature of such state actions, thereby allowing communal targeting to persist under the veil of legal neutrality. This erasure is particularly appalling given that punitive demolitions have been widely documented as a tactic used against Indian Muslims following instances of political dissent or protests against state policies. By refusing to name the affected community, the verdict not only whitewashes the state’s communal bias but also renders the suffering of Muslim families invisible within the nation’s legal discourse. This deliberate omission allows the state to continue its actions while claiming legal legitimacy, reducing demolitions to procedural matters rather than acts of systemic violence.

The enforceability of the Supreme Court’s guidelines on punitive demolitions remains deeply uncertain, much like the fate of the Tehseen Poonawalla judgment of 2018 on mob violence, which laid the foundation for curbing hate crimes but failed to translate into effective action on the ground. Despite the clear directives, lynchings and communal violence have continued with impunity, exposing the glaring gap between judicial pronouncements and executive enforcement. The same risk looms over the demolition guidelines.

Another serious concern over the guidelines’ enforceability is the continued demolitions despite the court’s directives. The recent contempt notice issued to Uttar Pradesh authorities for demolishing part of the Madni Mosque in Khushinagar in violation of the court’s order is a striking example. The incident highlights how state authorities continue to act with impunity—raising serious questions about the judiciary’s ability to check such excesses and ensure compliance.

While the Supreme Court’s verdict introduces certain procedural barriers against punitive demolitions, it does not dismantle the structural conditions that allow these demolitions to function as tools of state violence. The verdict, framed as a corrective measure, ultimately functions as a judicial compromise that protects the state from deeper scrutiny. The lack of independent oversight, the entrusting of key responsibilities to biased municipal and police officials, and the absence of clear penalties for non-compliance mean that these measures are likely to be circumvented in practice.

Without clear protections against communal targeting, retrospective justice for past victims, or a legal framework that prioritizes judicial oversight over executive discretion, the verdict serves more as an adjustment than an intervention against state violence. The absence of a clear stance on anti-Muslim targeting signals to the state that as long as legal formalities are observed, the political project of marginalisation can continue unimpeded. If justice is to be meaningful, it must go beyond procedural safeguards and dismantle the very conditions that allow violence to masquerade as governance.

SUPPORT US

We like bringing the stories that don’t get told to you. For that, we need your support. However small, we would appreciate it.