Documenting custodial violence: Reflections and further research – 5

In the concluding essay we discuss the challenges we faced and the scope for future research on accountability in custodial deaths cases in India. We also reflect on working on a project that is sensitive and politically charged in the current political environment, where trying to hold the State accountable for its actions has become dangerous and difficult. While we make reference to previously recommended police reforms to reduce police torture and improve accountability, we pose larger questions on the nature of accountability and state violence.

While tracking the 15 cases we discussed in the previous essays in this series we faced a number of challenges. Court documents are not easily available on online government portals, they are either not uploaded or not accessible. The names of victims are often spelt differently across news reports in English, which makes it hard to track cases accurately. There is a sense of fear and objective risk of harassment when trying to file Right to Information (RTI) requests in cases of custodial deaths given the ongoing persecution of RTI and human rights activists in India. We learnt this while speaking to various grassroots organizations and lawyers working closely with the courts and with families of victims in cases of custodial deaths. Due to the lapse of time since the cases first occurred, it was difficult to find lawyers or human rights organizations who still have documents and other material regarding the cases. The limitations of this project also include the lack of resources in tracking closely a larger number of cases and the heavy reliance on news reports in English dating back six years.

Further research on custodial deaths in India can involve speaking to the lawyers and families of the victims, interviewing police personnel and legal scholars. Speaking to journalists covering these cases would also help in getting a sense of the information asymmetry in terms of what is reported, what is hidden and what are the lengths that people go to recover and corroborate information. Interviews with human rights organizations could help in getting an overall picture of custodial deaths in India.

We filed a total of 45 RTI applications for the 15 cases from four states. For each of the cases, we filed an RTI with the police station where the victim was brought in or arrested or where the FIR was filed, the State Human Rights Commission (SHRC) and the National Human Rights Commission (NHRC). We received two responses from the concerned police authority and the SHRC mentioning that they would send the required information to us, however, we have not received any information from these two bodies at the time of writing. In one case, we received the response “court ticket not part of application fee” from the police authority in charge of handling RTI requests.

This project focuses exclusively on custodial violence and deaths in police and judicial custody. The Indian state perpetrates violence in other forms such as sexual violence and rape in custody, extra-judicial killings, torture in juvenile homes and de-addiction centers as well as violence and torture by the Indian military apparatus, especially in Jammu and Kashmir and the northeastern states. The Indian military function with impunity in many areas under the Armed Forces (Special Powers) Act (AFSPA), which grants special powers to the Indian Armed Forces. While this project does not address or focus on these other instances of violence, it is essential to mention them in order to highlight the scope and extent of violence perpetrated by the Indian state.

The shift from physical markers of custodial violence to scientific methods of interrogation are an invisible form of violence and have an impact on the victim’s mental health. Jinee Lokaneeta’s groundbreaking ethnography, Truth Machines: Policing, Violence, and Scientific Interrogations in India, studies the relationship between state power and legal violence through a study of forensic techniques. Lokaneeta argues that the use of interrogation techniques that focus on the mind rather than the body – such as brain scanning, narco analysis and lie detection – seek to replace third-degree torture and violence. Lokaneeta notes that this shift is also prompted by the fact that the Police negotiate two roles – the pastoral and the repressive and aim to avoid custodial deaths or physical signs of torture. Despite doubts and concerns over their validity, the adoption of “truth machines” or scientific methods was not met with much pushback. The Ministry of Home Affairs, ignoring its own scientific review committee, made these techniques a priority for police reform. Many of the High Courts also approved the use of these methods in an effort to move away from custodial violence, but in 2010 the Supreme Court disallowed the use of these scientific methods as well as the evidence obtained from them. However, since the Supreme Court did not fully ban the use of these methods, the Police continue to use these techniques and other emerging ones which are deemed unreliable.

Lokaneeta exposes the “scaffold of rule of law,” that hides violence behind procedures and depends on the Police, doctors and magistrates to perform the interrogation. She proposes the theory of a “contingent state” which allows State actors, such as the Police, doctors, forensic psychologists and judges to routinely indulge in violence. Lokaneeta rightly notes that the voices of those targeted will reveal the violence and that understanding the rule of law requires attention to the experience of those affected. It is only by revealing the scaffolding of the rule of law that one can actively resist it. Over the years, various bodies, commissions, human rights organizations and international bodies have proposed reforms to improve police accountability.

Artha Global’s 2022 report Prioritising Rule of Law and Police Reform in India suggests several reforms to improve police accountability including the need for a democratic internal organizational culture and improving institutional capacity along with improved training of police personnel for a community-oriented model of policing especially for vulnerable groups.

The 2016 HRW report Bound by Brotherhood: India’s Failure to End Killings in Police Custody has proposed detailed recommendations to concerned institutions. These recommendations include the Indian Parliament ratifying the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment, incorporating its provisions into domestic law and amending Section 36 of the Protection of Human Rights (Amendment) Act, 2006. This amendment would allow the NHRC to inquire into violations pending before other commissions or those that occurred more than one year before the complaint was filed to allow more victims to access the commission. The Union and State Home Ministries as well as the Police are also recommended to strictly enforce laws and guidelines on arrest and detention as set forth in the Code of Criminal Procedure and the Supreme Court’s D.K. Basu’s decision.

To ensure accountability for police misconduct, HRW noted that Police Complaints Authorities (PCAs) are set up in line with Supreme Court directives and are functional at both state and district levels. Another suggestion is to create an anonymous complaints line for victims and witnesses, including other police personnel to report misconduct. To bolster accountability mechanisms, under no circumstances should investigations ordered by external agencies such as the state human rights commissions be referred to police from the same police station implicated in the complaint. When police officers are identified in any First Information Report (FIR) regarding custodial abuse, they should be suspended until the incident is investigated and resolved, and there is a need to end the practice of transferring police alleged to have committed abuses.

The NHRC is recommended to end the practice of transferring cases filed with the NHRC to SHRCs unless given express consent to do so by complainants. This is based on the understanding that certain complaints may receive a fairer hearing by the NHRC. HRW also recommends ending the practice of filing multiple complaints for the same case. All complaints related to a case of custodial violence and death should be tied together so that they can easily be tracked for updates. The NHRC is also recommended to conduct more independent investigations into custodial deaths rather than relying heavily on magisterial and police inquiry reports. Despite these recommendations and the ones put forward in the 2009 HRW report, Broken System: Dysfunction, Abuse, and Impunity in the Indian Police, it remains to be seen when and how many of these proposed recommendations will be implemented.

Based on our research, we reiterate the necessity of reforming section 197 of the Code of Criminal Procedure (CrPC) so that prosecutors do not need to obtain government approval before pursuing charges against police in cases alleging arbitrary detention, torture, extrajudicial killings and other criminal acts. In many of the cases that we focused on, the NHRC closed the investigation after ordering interim compensation for the victims, not waiting to see if the compensation would be paid, or whether that ensured justice to the families of victims. We noted the threats and intimidation that families of victims of custodial deaths have to endure: it is necessary to take measures to protect them from coercion, violence or the threat of violence. We also noted that there is an urgent need to provide support and resources for grassroots networks and civil society organizations that provide direct assistance to the families and victims of police abuse and are engaged in years-long fight for justice.

In a liberal democracy, the rights of a person are a core value protected by the law and implemented through state actors. The Police is one such state actor. The Indian Constitution ensures that every citizen is guaranteed the right to life and personal liberty. However, as Jinee Lokaneeta notes, in India the Police are the “most visible site of state power in their everyday operations.”

Documenting the global history of torture, political scientist Darius Rejali in his book Torture and Democracy (2007) notes that the Police and the military in main democratic states such as France, England and USA were leaders in adapting and innovating techniques of torture. Rejali offers an explanation for this link between democracies and torture: public monitoring by the press, politicians, international and national human rights organizations is a core value in democracies and hence coercive techniques of torture were developed and implemented to escape or limit accountability. Torture, which is a pervasive open secret is also not defined in the Indian Penal Code (IPC). The Prevention of Torture bill was first introduced in the Lok Sabha, India’s lower house of Parliament in 2010. The Rajya Sabha referred the bill to a Select Committee which proposed amendments to make it more compliant with the United Nations Convention Against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment to which India is a signatory, and the committee presented its findings in December 2010. However, the bill lapsed with the dissolution of the 15th Lok Sabha.

In October 2017, the Law Commission of India published their report on “Implementation of the United Nations Convention against Torture and other Cruel, Inhuman and Degrading Treatment or Punishment through Legislation.” In 2017, The Prevention of Torture bill was introduced as a private member bill in the Rajya Sabha but was not enacted. The same bill was introduced on 9 February 2018 as a private member bill in the Lok Sabha, but the bill lapsed due to the dissolution of the 16th Lok Sabha. A modified bill called the Prevention of Torture and Atrocities (By Public Servants) bill, 2019 was introduced in the Lok Sabha in December 2021 and is pending.

The Prevention of Torture bill offers the following definition of torture: “Whoever, being a public servant or being abetted by a public servant or with the consent or acquiescence of a public servant, intentionally does any act for the purposes to punish or to obtain information from any person, whether in police custody or otherwise, which causes,— (i) grievous hurt to any person; or (ii) danger to life, limb or health (whether mental or physical) of any person, is said to inflict torture.” Yet, the delay and failure to pass the law highlights the lack of incentive in holding public officials accountable. No legislation has been passed to define, condemn and take action against torture by public officials in India. This, yet again, brings up questions regarding the identity of the perpetrator, the ideological leanings of the State and the identity of the victim. Torture then becomes a tool to target certain groups and this discrimination is based on religion, caste, class or ideological associations.

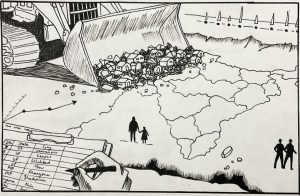

Custodial violence is disproportionately borne by poor and socially vulnerable groups, including Dalits, Adivasis, migrants, LGBTQ communities and religious minorities. While it is a known, pervasive and routine phenomenon, it needs to be documented, highlighted, addressed and challenged, irrespective of how much time has passed since the incident of violence occurred. The Indian State does not have the right or power to enforce and perpetrate violence and needs to be held accountable for its actions. Allowing the State to function with impunity is tantamount to the undermining of the Constitution and its ideals. A democracy thrives only when every individual is able to enjoy their rights equally and live without the fear of a violent State.

This research is built on the extensive work done by lawyers, researchers, human rights activists, journalists, families of victims seeking justice, local organizations and networks. We would like to extend our gratitude to all those who have influenced our work. While our attempt is neither comprehensive nor conclusive, we hope that the questions and limitations of this project will open up further research and engagement with these issues.

For this series of essays on judicial and administrative accountability on custodial deaths in India, we would like to acknowledge and thank the following people: Venkatesh Nayak from Commonwealth Human Rights Initiative (CHRI) for initial conversations and guidance on the project; Jayshree Bajoria, senior researcher at the Human Rights Watch (HRW) for guidance on the project; V. Geetha, feminist activist and scholar for documents on cases of custodial deaths in Tamil Nadu ; Shailesh Poddar, a lawyer based in Jharkhand and Delhi for assistance on accessing case documents and assistance with RTI applications; Raja Bagga, lawyer and researcher at the Jindal Global Law School for assistance on the study and with RTI applications; Kirity Roy at MASUM, for documents on cases of custodial deaths in West Bengal; Lateef Mohammed Khan at Civil Liberties Monitoring Committee (CLMC) for documents on cases of custodial deaths in Telangana; Leslie Martin for help in contacts for the project; Jinee Lokaneeta for guidance on the project and Amala Dasarathi, lawyer and legal researcher for assistance on accessing case documents. We would also like to thank Jayshree Bajoria, Raja Bagga and Jinee Lokaneeta for reviewing the essays, and Francesca Recchia for editorial support.

We would also like to thank The Thakur Foundation for providing support and funding for this project.

Related Posts

Documenting custodial violence: Reflections and further research – 5

In the concluding essay we discuss the challenges we faced and the scope for future research on accountability in custodial deaths cases in India. We also reflect on working on a project that is sensitive and politically charged in the current political environment, where trying to hold the State accountable for its actions has become dangerous and difficult. While we make reference to previously recommended police reforms to reduce police torture and improve accountability, we pose larger questions on the nature of accountability and state violence.

While tracking the 15 cases we discussed in the previous essays in this series we faced a number of challenges. Court documents are not easily available on online government portals, they are either not uploaded or not accessible. The names of victims are often spelt differently across news reports in English, which makes it hard to track cases accurately. There is a sense of fear and objective risk of harassment when trying to file Right to Information (RTI) requests in cases of custodial deaths given the ongoing persecution of RTI and human rights activists in India. We learnt this while speaking to various grassroots organizations and lawyers working closely with the courts and with families of victims in cases of custodial deaths. Due to the lapse of time since the cases first occurred, it was difficult to find lawyers or human rights organizations who still have documents and other material regarding the cases. The limitations of this project also include the lack of resources in tracking closely a larger number of cases and the heavy reliance on news reports in English dating back six years.

Further research on custodial deaths in India can involve speaking to the lawyers and families of the victims, interviewing police personnel and legal scholars. Speaking to journalists covering these cases would also help in getting a sense of the information asymmetry in terms of what is reported, what is hidden and what are the lengths that people go to recover and corroborate information. Interviews with human rights organizations could help in getting an overall picture of custodial deaths in India.

We filed a total of 45 RTI applications for the 15 cases from four states. For each of the cases, we filed an RTI with the police station where the victim was brought in or arrested or where the FIR was filed, the State Human Rights Commission (SHRC) and the National Human Rights Commission (NHRC). We received two responses from the concerned police authority and the SHRC mentioning that they would send the required information to us, however, we have not received any information from these two bodies at the time of writing. In one case, we received the response “court ticket not part of application fee” from the police authority in charge of handling RTI requests.

This project focuses exclusively on custodial violence and deaths in police and judicial custody. The Indian state perpetrates violence in other forms such as sexual violence and rape in custody, extra-judicial killings, torture in juvenile homes and de-addiction centers as well as violence and torture by the Indian military apparatus, especially in Jammu and Kashmir and the northeastern states. The Indian military function with impunity in many areas under the Armed Forces (Special Powers) Act (AFSPA), which grants special powers to the Indian Armed Forces. While this project does not address or focus on these other instances of violence, it is essential to mention them in order to highlight the scope and extent of violence perpetrated by the Indian state.

The shift from physical markers of custodial violence to scientific methods of interrogation are an invisible form of violence and have an impact on the victim’s mental health. Jinee Lokaneeta’s groundbreaking ethnography, Truth Machines: Policing, Violence, and Scientific Interrogations in India, studies the relationship between state power and legal violence through a study of forensic techniques. Lokaneeta argues that the use of interrogation techniques that focus on the mind rather than the body – such as brain scanning, narco analysis and lie detection – seek to replace third-degree torture and violence. Lokaneeta notes that this shift is also prompted by the fact that the Police negotiate two roles – the pastoral and the repressive and aim to avoid custodial deaths or physical signs of torture. Despite doubts and concerns over their validity, the adoption of “truth machines” or scientific methods was not met with much pushback. The Ministry of Home Affairs, ignoring its own scientific review committee, made these techniques a priority for police reform. Many of the High Courts also approved the use of these methods in an effort to move away from custodial violence, but in 2010 the Supreme Court disallowed the use of these scientific methods as well as the evidence obtained from them. However, since the Supreme Court did not fully ban the use of these methods, the Police continue to use these techniques and other emerging ones which are deemed unreliable.

Lokaneeta exposes the “scaffold of rule of law,” that hides violence behind procedures and depends on the Police, doctors and magistrates to perform the interrogation. She proposes the theory of a “contingent state” which allows State actors, such as the Police, doctors, forensic psychologists and judges to routinely indulge in violence. Lokaneeta rightly notes that the voices of those targeted will reveal the violence and that understanding the rule of law requires attention to the experience of those affected. It is only by revealing the scaffolding of the rule of law that one can actively resist it. Over the years, various bodies, commissions, human rights organizations and international bodies have proposed reforms to improve police accountability.

Artha Global’s 2022 report Prioritising Rule of Law and Police Reform in India suggests several reforms to improve police accountability including the need for a democratic internal organizational culture and improving institutional capacity along with improved training of police personnel for a community-oriented model of policing especially for vulnerable groups.

The 2016 HRW report Bound by Brotherhood: India’s Failure to End Killings in Police Custody has proposed detailed recommendations to concerned institutions. These recommendations include the Indian Parliament ratifying the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment, incorporating its provisions into domestic law and amending Section 36 of the Protection of Human Rights (Amendment) Act, 2006. This amendment would allow the NHRC to inquire into violations pending before other commissions or those that occurred more than one year before the complaint was filed to allow more victims to access the commission. The Union and State Home Ministries as well as the Police are also recommended to strictly enforce laws and guidelines on arrest and detention as set forth in the Code of Criminal Procedure and the Supreme Court’s D.K. Basu’s decision.

To ensure accountability for police misconduct, HRW noted that Police Complaints Authorities (PCAs) are set up in line with Supreme Court directives and are functional at both state and district levels. Another suggestion is to create an anonymous complaints line for victims and witnesses, including other police personnel to report misconduct. To bolster accountability mechanisms, under no circumstances should investigations ordered by external agencies such as the state human rights commissions be referred to police from the same police station implicated in the complaint. When police officers are identified in any First Information Report (FIR) regarding custodial abuse, they should be suspended until the incident is investigated and resolved, and there is a need to end the practice of transferring police alleged to have committed abuses.

The NHRC is recommended to end the practice of transferring cases filed with the NHRC to SHRCs unless given express consent to do so by complainants. This is based on the understanding that certain complaints may receive a fairer hearing by the NHRC. HRW also recommends ending the practice of filing multiple complaints for the same case. All complaints related to a case of custodial violence and death should be tied together so that they can easily be tracked for updates. The NHRC is also recommended to conduct more independent investigations into custodial deaths rather than relying heavily on magisterial and police inquiry reports. Despite these recommendations and the ones put forward in the 2009 HRW report, Broken System: Dysfunction, Abuse, and Impunity in the Indian Police, it remains to be seen when and how many of these proposed recommendations will be implemented.

Based on our research, we reiterate the necessity of reforming section 197 of the Code of Criminal Procedure (CrPC) so that prosecutors do not need to obtain government approval before pursuing charges against police in cases alleging arbitrary detention, torture, extrajudicial killings and other criminal acts. In many of the cases that we focused on, the NHRC closed the investigation after ordering interim compensation for the victims, not waiting to see if the compensation would be paid, or whether that ensured justice to the families of victims. We noted the threats and intimidation that families of victims of custodial deaths have to endure: it is necessary to take measures to protect them from coercion, violence or the threat of violence. We also noted that there is an urgent need to provide support and resources for grassroots networks and civil society organizations that provide direct assistance to the families and victims of police abuse and are engaged in years-long fight for justice.

In a liberal democracy, the rights of a person are a core value protected by the law and implemented through state actors. The Police is one such state actor. The Indian Constitution ensures that every citizen is guaranteed the right to life and personal liberty. However, as Jinee Lokaneeta notes, in India the Police are the “most visible site of state power in their everyday operations.”

Documenting the global history of torture, political scientist Darius Rejali in his book Torture and Democracy (2007) notes that the Police and the military in main democratic states such as France, England and USA were leaders in adapting and innovating techniques of torture. Rejali offers an explanation for this link between democracies and torture: public monitoring by the press, politicians, international and national human rights organizations is a core value in democracies and hence coercive techniques of torture were developed and implemented to escape or limit accountability. Torture, which is a pervasive open secret is also not defined in the Indian Penal Code (IPC). The Prevention of Torture bill was first introduced in the Lok Sabha, India’s lower house of Parliament in 2010. The Rajya Sabha referred the bill to a Select Committee which proposed amendments to make it more compliant with the United Nations Convention Against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment to which India is a signatory, and the committee presented its findings in December 2010. However, the bill lapsed with the dissolution of the 15th Lok Sabha.

In October 2017, the Law Commission of India published their report on “Implementation of the United Nations Convention against Torture and other Cruel, Inhuman and Degrading Treatment or Punishment through Legislation.” In 2017, The Prevention of Torture bill was introduced as a private member bill in the Rajya Sabha but was not enacted. The same bill was introduced on 9 February 2018 as a private member bill in the Lok Sabha, but the bill lapsed due to the dissolution of the 16th Lok Sabha. A modified bill called the Prevention of Torture and Atrocities (By Public Servants) bill, 2019 was introduced in the Lok Sabha in December 2021 and is pending.

The Prevention of Torture bill offers the following definition of torture: “Whoever, being a public servant or being abetted by a public servant or with the consent or acquiescence of a public servant, intentionally does any act for the purposes to punish or to obtain information from any person, whether in police custody or otherwise, which causes,— (i) grievous hurt to any person; or (ii) danger to life, limb or health (whether mental or physical) of any person, is said to inflict torture.” Yet, the delay and failure to pass the law highlights the lack of incentive in holding public officials accountable. No legislation has been passed to define, condemn and take action against torture by public officials in India. This, yet again, brings up questions regarding the identity of the perpetrator, the ideological leanings of the State and the identity of the victim. Torture then becomes a tool to target certain groups and this discrimination is based on religion, caste, class or ideological associations.

Custodial violence is disproportionately borne by poor and socially vulnerable groups, including Dalits, Adivasis, migrants, LGBTQ communities and religious minorities. While it is a known, pervasive and routine phenomenon, it needs to be documented, highlighted, addressed and challenged, irrespective of how much time has passed since the incident of violence occurred. The Indian State does not have the right or power to enforce and perpetrate violence and needs to be held accountable for its actions. Allowing the State to function with impunity is tantamount to the undermining of the Constitution and its ideals. A democracy thrives only when every individual is able to enjoy their rights equally and live without the fear of a violent State.

This research is built on the extensive work done by lawyers, researchers, human rights activists, journalists, families of victims seeking justice, local organizations and networks. We would like to extend our gratitude to all those who have influenced our work. While our attempt is neither comprehensive nor conclusive, we hope that the questions and limitations of this project will open up further research and engagement with these issues.

For this series of essays on judicial and administrative accountability on custodial deaths in India, we would like to acknowledge and thank the following people: Venkatesh Nayak from Commonwealth Human Rights Initiative (CHRI) for initial conversations and guidance on the project; Jayshree Bajoria, senior researcher at the Human Rights Watch (HRW) for guidance on the project; V. Geetha, feminist activist and scholar for documents on cases of custodial deaths in Tamil Nadu ; Shailesh Poddar, a lawyer based in Jharkhand and Delhi for assistance on accessing case documents and assistance with RTI applications; Raja Bagga, lawyer and researcher at the Jindal Global Law School for assistance on the study and with RTI applications; Kirity Roy at MASUM, for documents on cases of custodial deaths in West Bengal; Lateef Mohammed Khan at Civil Liberties Monitoring Committee (CLMC) for documents on cases of custodial deaths in Telangana; Leslie Martin for help in contacts for the project; Jinee Lokaneeta for guidance on the project and Amala Dasarathi, lawyer and legal researcher for assistance on accessing case documents. We would also like to thank Jayshree Bajoria, Raja Bagga and Jinee Lokaneeta for reviewing the essays, and Francesca Recchia for editorial support.

We would also like to thank The Thakur Foundation for providing support and funding for this project.

SUPPORT US

We like bringing the stories that don’t get told to you. For that, we need your support. However small, we would appreciate it.