Launching our Demolitions Database: The map, the methodology, and the narratives

Punitive demolitions have emerged as a worrying tool of governance in India. In several instances across various states, authorities have deployed bulldozers to raze the homes of people accused of crimes, involved in protests, or belonging to communities viewed with hostility by the regime. Ostensibly carried out under the guise of removing “illegal” structures, these demolitions often occur immediately after an incident of unrest or dissent—suggesting a motive of retribution rather than routine law enforcement. This trend, unironically dubbed “bulldozer justice” by a country increasingly tolerant of Hindutva policies, represents a form of extrajudicial punishment where state governments use demolition drives to collectively punish individuals and families, without due process. Documentation of these punitive demolitions is critical to hold state actions accountable and bring transparency to this new facet of state violence.

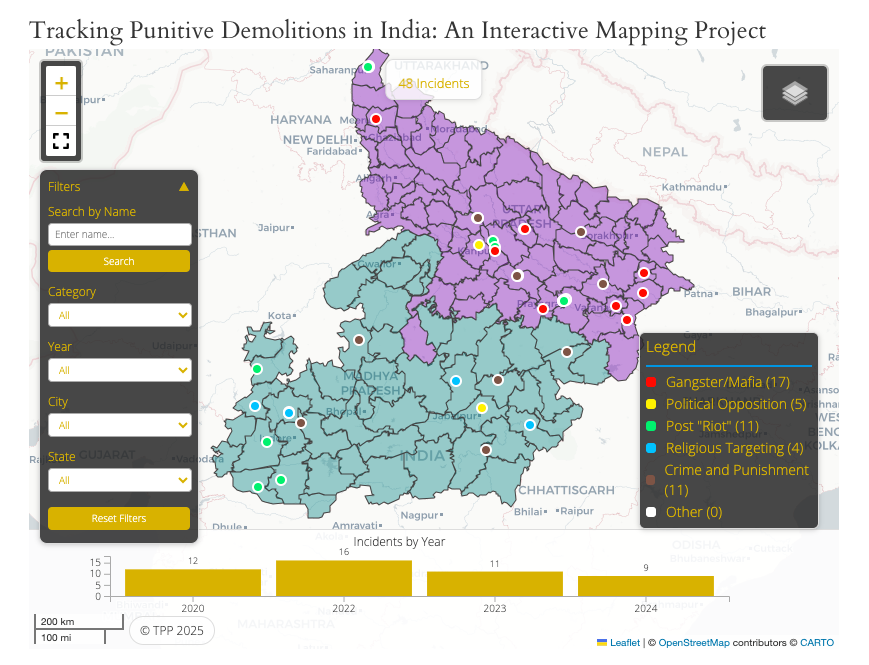

The Demolitions Project enters this fraught landscape as a unique and timely intervention. By systematically documenting incidents of state-led demolitions, the project shines a light on a pattern of governance that might otherwise be obscured by official rhetoric or sporadic news coverage. Crucially, the project adopts a qualitative and quantitative approach for this research. At a qualitative level, the project seeks to understand what it means to have one’s property demolished without legal sanction, as an act of punitive, and often religious, violence. To do so, it conducts detailed interviews with victims of demolitions and their families, published as individual narratives in our Profiles of Demolitions series. At the quantitative level, the project records the demolitions, their purported justifications, and their details, in an interactive map, Tracking Punitive Demolitions in India.

Our documentation—which including dates, locations, context, and testimonies—transforms what could be dismissed as isolated events into a coherent body of evidence. This is vital for accountability: when authorities know their actions are being recorded and scrutinised, it creates pressure for adherence to legal norms and opens avenues for redress. The Demolitions Project and our interactive map is not just another dataset; it is a living archive and investigative tool that strengthens the broader discourse on state violence in India. It emphasises that these demolitions are not random or “routine” administrative actions, but part of a deliberate strategy of governance that demands public attention.

Bridging gaps in existing documentation

Most research on demolitions by authorities in India focuses on housing rights, and case studies on violations of legal processes and human rights. Existing databases and research—for example, annual surveys of forced evictions by housing-rights organisations—have documented the sheer scale of demolitions and evictions across the country. For instance, the Housing and Land Rights Network (HLRN) reported that in 2022-2023 alone, Indian authorities demolished over 1.53 lakh homes, displacing roughly 7.4 lakh people. In nearly all documented cases, due process requirements were ignored, resulting in gross human rights violations.

However, this documentation aggregates all types of evictions—from slum clearance for development projects to infrastructure-driven displacements—without isolating the recent phenomenon of demolitions as punitive collective punishment. The focus has historically been on housing legality and policy failures rather than explicitly on state reprisal or communal targeting. This is a critical gap: a demolition executed as an act of vengeance or intimidation by the state is qualitatively different from an eviction for a public project, even if both violate housing rights. Some recent reports, such as Amnesty’s crucial work on “Bulldozer Injustice,” provide a broad human-rights assessment and legal critique of punitive demolitions.

The Demolitions Project takes this research further with evolving and interactive documentation that brings together the important quantitative and qualitative analysis that is necessary to understand the phenomenon. Our documentation explicitly links each documented demolition to the socio-political context in which it occurred.

This project categorises demolitions based on their motive and circumstance, such as acts of retribution following a protest or riot; measures targeting a particular ethnic or religious community; or other forms of extrajudicial “justice.” By tagging and describing cases in terms of political, communal, or legal pretexts, the project foregrounds the punitive governance aspect that is missing in existing research. For example, many of the documented demolitions on the map follow incidents of communal violence or civil protest, indicating they were a form of collective punishment against a community or group. Others coincide with crackdowns on alleged links to the “mafia,” where due process was sidestepped in favour of immediate visible action.

By organising the data in this way, the project ensures these events are not treated as isolated administrative actions. Instead, they are presented as part of a broader pattern of state behaviour. This approach goes beyond existing documentation by marrying legal analysis with political context: each demolition is evidence of a governance strategy that leverages state power to punish or subjugate. In short, the project reframes demolitions from being merely a housing rights issue to being a democratic rights issue—a matter of state overreach, constitutional violations, and targeted violence

A continuously evolving archive

Another aspect that sets The Demolitions Project’s demolitions documentation apart is its commitment to being a continuously evolving archive of state violence. Rather than a one-off report that captures a snapshot in time, the interactive map and its accompanying database are designed to be regularly updated as new cases emerge. This ongoing nature is crucial because the phenomenon of punitive demolitions is itself ongoing. This makes the archive a living document of state actions. The importance of this cannot be overstated: patterns of repression can change over time, and a static report can quickly become outdated or incomplete.

Maintaining a live archive also means the project can capture nuances and new patterns as they develop. Authoritarian tactics evolve—for instance, if courts begin to clamp down on outright illegal demolitions, authorities might adapt by creating paper trails or new ordinances to justify them. The continuous documentation can catch such shifts: are states issuing new laws to legalise punitive demolitions? Are there changes in the official rationale given over time? The archive can be annotated with these details. Over the long term, this creates a robust historical record that can inform scholarly research and memory.

From data to narrative

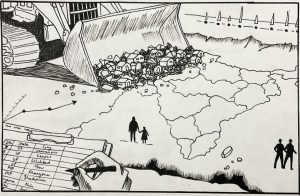

While compiling data is essential, The Demolitions Project recognises that raw numbers alone cannot convey the human impact or political significance of state-led demolitions. One of the standout features of the project is its interactive map, which is far more than a spreadsheet of incidents—it is a storytelling platform. The map allows users to visualise the geographic spread and frequency of demolitions, offering an immediate sense of scope and pattern. With a quick glance, viewers can see clusters of demolition markers in certain states or regions, correlating with specific time periods or political regimes.

This visual aggregation helps transform abstract data into a tangible landscape of state violence. For instance, seeing multiple demolition sites dotting the map in Uttar Pradesh or Madhya Pradesh—states noted for frequent bulldozer actions—powerfully illustrates how normalised this practice has become in some areas. Such visualisation invites the public to engage with the data: one can zoom in on a city to find details of a particular case; use the filters to understand the frequency of different categories of demolitions; search for specific cases of demolitions by name; or scroll through time to watch the phenomenon unfold. In doing so, the project turns statistics into an interactive experience, making the reality of state excesses more accessible and harder to ignore.

Beyond the map’s pins and polygons, The Demolitions Project emphasises narrative and testimony, thereby turning data into compelling stories. Each demolition incident documented is accompanied by context – the official reason given, the timeline of events, and crucially in some cases, the voices and experiences of those directly affected. Through our Profiles of Demolitions, and the details, articles, and embedded media for the mapped incidents, the project highlights individual and community experiences behind each demolition.

This narrative-driven documentation brings forward the trauma and injustice in ways that pure data cannot capture. Our storytelling in documentation serves to bridge the emotional gap that often exists between human rights reports and public perception. By incorporating testimonies, photographs, and personal details, the demolitions map project invites empathy and public outrage, translating what might seem like dry facts into urgent moral questions. In a country as vast as India, it is easy for individual stories of injustice to get lost in the din; The Demolitions Project’s work ensures these stories are both heard and remembered, thereby making state violence visible and palpable to a wider audience.

Importantly, this interactive, narrative-based approach democratises information about state violence. The map presents information in a user-friendly format that journalists, students, activists, and ordinary citizens can all explore. It is akin to a public archive that one can walk through, case by case, story by story. By lowering the barriers to accessing detailed documentation, The Demolitions Project enables a broader segment of society to inform themselves about the realities of “bulldozer raj.”

In doing so, it cultivates a more informed public discourse. When people can point to a map and recount what happened to families in their own or neighboring towns, the issue of demolitions moves from the abstract realm of policy to the concrete realm of lived experience. This transformation of data into narrative is a powerful added value—it not only documents state violence but does so in a way that galvanises understanding and engagement.

Countering media and state narratives

One of the most significant added values lies in challenging and countering the dominant narratives presented by both the state and sections of the media. In many of the documented cases, the official line and its amplification in mainstream discourse followed a predictable pattern: authorities justify a demolition as a necessary action against “criminal elements,” “rioters,” or “anti-nationals,” and claim that the structures were illegal anyway. Large sections of the media then parrot these claims, framing the story as one of law and order, rather than as a human rights issue.

The very term “bulldozer justice,” which has gained currency, reflects this narrative of swift, no-nonsense action. In some TV studios and political rallies, the bulldozer is lionised as delivering instant justice that courts allegedly fail to provide. This discourse conveniently masks the reality of what these demolitions entail: innocent family members thrown on the street, livelihoods crushed, an endorsement of collective punishment, and entire communities terrorised without trial. By humanising the victims and meticulously documenting the facts, The Demolitions Project provides a powerful counter-narrative.

Through its map and associated stories, the project reframes the victims of demolitions as citizens with rights, rather than nameless wrongdoers. Each pin on the map is not just a structure; it represents people—often marginalised due to their religion—whose lives were upended. It shows that those affected are frequently ordinary law-abiding people who were caught in a wave of collective retribution. By presenting evidence from the ground, The Demolitions Project directly confronts this propaganda.

Moreover, The Demolitions Project’s narrative approach engages public empathy, which is crucial to countering state narratives that often dehumanise those affected. By reading the personal story of a family – their terror as the bulldozer arrived, their loss of heirlooms and documents in the rubble, the children’s trauma of seeing their home destroyed. The project brings forward a much-needed human rights perspective into public discourse. In a media environment where the voices of victims are seldom given equal platform as the voices of officials, this documentation elevates those suppressed voices. It brings forth the testimonies of people who ask the very simple question: “Sab kuch ek taraf, lekin aap kisi ka ghar kaise gira sakte hain?” (Setting aside everything, how can you demolish someone’s home?)

In doing so, it disrupts the state’s propaganda cycle. It becomes harder for authorities to paint a rosy picture of “justice served” when a well-documented counternarrative – complete with maps, data and human stories – is widely accessible, painting a very different picture of injustice and trauma inflicted.

Situating demolitions within a larger system of state violence

The Demolitions Project also situates these incidents within the broader architecture of state violence and authoritarian governance in India. This broader view is crucial: these demolitions are not random or apolitical; they often coincide with other forms of coercion such as police crackdowns, mass arrests, internet shutdowns, or discriminatory laws. By mapping demolitions alongside their causes, the project helps illustrate that the demolition of homes has become another weapon in the state’s arsenal—one that bypasses judicial processes, much like illegal detentions or extrajudicial encounters. In other words, home demolitions have become a visible symbol of a state machinery willing to dispense punishment outside the courtroom, reinforcing an overall climate of fear.

The project’s research and categorisation make clear that these demolitions are deeply enmeshed with Hindutva politics and social hierarchies. A striking pattern in the data is the disproportionate targeting of Muslim neighborhoods and properties, especially in BJP-ruled states. This mirrors the broader project of Hindu majoritarianism, where state violence often finds its justifications in demonising minority communities as threats.

Through its holistic approach, The Demolitions Project offers a framework for analysis: it encourages observers to examine not just the legal violation (demolition without due process) but the political logic behind these acts. The data can be used to ask questions like: are demolitions spiking around election times or major protests? Do they correlate with speeches by political leaders advocating “tough action”?

Preliminary analysis

Our current dataset reveals that the most frequently targeted category is that of individuals labelled as “Gangster/Mafia”—a classification applied broadly to politicians, businessmen, and associates of criminalised figures, particularly those from Muslim communities. Many of these demolitions are tied to high-profile figures such as Atiq Ahmed and Mukhtar Ansari, whose properties, as well as those of their relatives and associates, have been repeatedly razed. This reflects a broader strategy of punitive demolitions aimed at dismantling networks associated with figures deemed adversarial to the state.

Another significant category is “Political Opposition,” where demolitions have targeted opposition leaders and their families, particularly those affiliated with the Samajwadi Party and Bahujan Samaj Party. This suggests a pattern of using state machinery to suppress political dissent. Additionally, there are cases of demolitions categorised as “Post Riot” actions, where properties of individuals accused of participating in protests or communal disturbances were destroyed. Notably, several of these cases relate to protests against derogatory remarks about the Prophet Muhammad, indicating a punitive response to Muslim political expression.

Geographically, Prayagraj emerges as a focal point of the demolitions in Uttar Pradesh, with numerous actions taken against individuals linked to Atiq Ahmed. Other key locations include Lucknow, Kanpur, Saharanpur, and Mau. The timeline of these demolitions reveals that they intensified around politically sensitive moments, such as after protests or ahead of elections, further indicating a strategic use of demolition as a tool of state violence.

The data from Madhya Pradesh (MP) reveals a pattern of demolitions following communal violence, with the “Post Riot” category being the most frequent, accounting for six recorded instances. Other notable categories include “Crime and Punishment” and “Religious Targeting,” which suggest demolitions targeting individuals accused of criminal activities or belonging to specific religious groups. Interestingly, there is also an overlap in the two categories, reflecting how state narratives frame demolitions both as law enforcement and as communal actions.

Geographically, demolitions are scattered across multiple districts, with Ujjain, Dhar, Khargone, and Dewas among the affected areas. Notably, the demolitions in Khargone occurred across multiple localities, indicating a large-scale action, possibly targeting an entire community. Many of these demolitions seem to be responses to protests or unrest, aligning with broader state patterns of using bulldozers to collectively punish Muslim neighbourhoods in the wake of communal violence. These demolitions align with the broader Hindutva project of reconfiguring urban spaces to marginalise Muslim presence.

Limitations and Conclusion

While The Demolitions Project marks a critical intervention in tracking and analysing punitive demolitions in India, it is not without its limitations. The current scope of our documentation is geographically uneven, with a concentrated focus on states like Uttar Pradesh and Madhya Pradesh, where such demolitions have been highly visible and politically significant. While we are in the process of expanding our dataset to include additional regions such as Delhi and Haryana, other crucial states like Assam and Gujarat, where state-led demolition practices intersect with long-standing communal violence, remain outside the present scope of our research. This gap reflects both the challenges of access and the constraints of a small team working within a difficult and often hostile information environment.

Although we have aimed to document as many incidents as possible, this archive is not exhaustive. It is likely that some cases have gone unrecorded, either due to a lack of media coverage, suppressed local reporting, or the logistical and safety challenges of conducting fieldwork in certain regions. Additionally, while the Profiles of Demolitions series is central to our goal of centering survivor voices and contextualising the lived experience of state violence, such in-depth narrative accounts currently exist for only a subset of the demolitions we have recorded. The limitations here are both ethical and practical: interviews require trust, time, and care, and many families fear retaliation or are retraumatised by the act of retelling.

We remain committed to expanding this narrative layer of our documentation while upholding principles of consent, care, and dignity. Our work unfolds in a landscape where state repression, media complicity, and public desensitisation create formidable barriers to accountability. Despite these constraints, we believe the act of witnessing and recording itself is a form of resistance. These limitations are reminders of the urgency and complexity of the task at hand, and they mark areas where solidarity, collaboration, and continued research are most needed.

Rigorous documentation plays a pivotal role in resisting state violence and shaping the public discourse on issues of governance and justice. Through its semi-academic yet accessible approach, the project illuminates how punitive demolitions in India are not just about buildings being torn down, they are about the tearing apart of the rule of law and civil liberties. It recontextualises demolitions as part of a deliberate strategy of extrajudicial punishment and intimidation. This added framing is invaluable: it helps the public and policymakers alike to see the big picture of how seemingly local incidents connect to national patterns of authoritarian behavior.

The demolitions map’s blend of data and narrative has expanded the toolkit for accountability. It serves simultaneously as an archive of evidence, a platform for victim testimonials, and an analytical lens to view state actions. In the broader discourse on punitive demolitions and state violence, this work provides a reference point that did not exist before. Advocacy groups and legal activists would be able to invoke the patterns and cases highlighted by the project when arguing against the government’s heavy-handed tactics.

Crucially, The Demolitions Project underscores that memory is a form of resistance: by remembering and recording each demolition, it denies the state the power to erase these incidents from public consciousness. It tells the government that these acts are being watched, analysed, and will be recalled in history. It is through such collective efforts that we can hope to rein in punitive demolitions, restore adherence to due process, and hold the state accountable to the principles of justice and equality that are the bedrock of any democracy. It is, in effect, a bulwark defending the idea that no government can act with impunity when citizens wield the tools of truth and documentation.

Related Posts

Punitive demolitions have emerged as a worrying tool of governance in India. In several instances across various states, authorities have deployed bulldozers to raze the homes of people accused of crimes, involved in protests, or belonging to communities viewed with hostility by the regime. Ostensibly carried out under the guise of removing “illegal” structures, these demolitions often occur immediately after an incident of unrest or dissent—suggesting a motive of retribution rather than routine law enforcement. This trend, unironically dubbed “bulldozer justice” by a country increasingly tolerant of Hindutva policies, represents a form of extrajudicial punishment where state governments use demolition drives to collectively punish individuals and families, without due process. Documentation of these punitive demolitions is critical to hold state actions accountable and bring transparency to this new facet of state violence.

The Demolitions Project enters this fraught landscape as a unique and timely intervention. By systematically documenting incidents of state-led demolitions, the project shines a light on a pattern of governance that might otherwise be obscured by official rhetoric or sporadic news coverage. Crucially, the project adopts a qualitative and quantitative approach for this research. At a qualitative level, the project seeks to understand what it means to have one’s property demolished without legal sanction, as an act of punitive, and often religious, violence. To do so, it conducts detailed interviews with victims of demolitions and their families, published as individual narratives in our Profiles of Demolitions series. At the quantitative level, the project records the demolitions, their purported justifications, and their details, in an interactive map, Tracking Punitive Demolitions in India.

Our documentation—which including dates, locations, context, and testimonies—transforms what could be dismissed as isolated events into a coherent body of evidence. This is vital for accountability: when authorities know their actions are being recorded and scrutinised, it creates pressure for adherence to legal norms and opens avenues for redress. The Demolitions Project and our interactive map is not just another dataset; it is a living archive and investigative tool that strengthens the broader discourse on state violence in India. It emphasises that these demolitions are not random or “routine” administrative actions, but part of a deliberate strategy of governance that demands public attention.

Bridging gaps in existing documentation

Most research on demolitions by authorities in India focuses on housing rights, and case studies on violations of legal processes and human rights. Existing databases and research—for example, annual surveys of forced evictions by housing-rights organisations—have documented the sheer scale of demolitions and evictions across the country. For instance, the Housing and Land Rights Network (HLRN) reported that in 2022-2023 alone, Indian authorities demolished over 1.53 lakh homes, displacing roughly 7.4 lakh people. In nearly all documented cases, due process requirements were ignored, resulting in gross human rights violations.

However, this documentation aggregates all types of evictions—from slum clearance for development projects to infrastructure-driven displacements—without isolating the recent phenomenon of demolitions as punitive collective punishment. The focus has historically been on housing legality and policy failures rather than explicitly on state reprisal or communal targeting. This is a critical gap: a demolition executed as an act of vengeance or intimidation by the state is qualitatively different from an eviction for a public project, even if both violate housing rights. Some recent reports, such as Amnesty’s crucial work on “Bulldozer Injustice,” provide a broad human-rights assessment and legal critique of punitive demolitions.

The Demolitions Project takes this research further with evolving and interactive documentation that brings together the important quantitative and qualitative analysis that is necessary to understand the phenomenon. Our documentation explicitly links each documented demolition to the socio-political context in which it occurred.

This project categorises demolitions based on their motive and circumstance, such as acts of retribution following a protest or riot; measures targeting a particular ethnic or religious community; or other forms of extrajudicial “justice.” By tagging and describing cases in terms of political, communal, or legal pretexts, the project foregrounds the punitive governance aspect that is missing in existing research. For example, many of the documented demolitions on the map follow incidents of communal violence or civil protest, indicating they were a form of collective punishment against a community or group. Others coincide with crackdowns on alleged links to the “mafia,” where due process was sidestepped in favour of immediate visible action.

By organising the data in this way, the project ensures these events are not treated as isolated administrative actions. Instead, they are presented as part of a broader pattern of state behaviour. This approach goes beyond existing documentation by marrying legal analysis with political context: each demolition is evidence of a governance strategy that leverages state power to punish or subjugate. In short, the project reframes demolitions from being merely a housing rights issue to being a democratic rights issue—a matter of state overreach, constitutional violations, and targeted violence

A continuously evolving archive

Another aspect that sets The Demolitions Project’s demolitions documentation apart is its commitment to being a continuously evolving archive of state violence. Rather than a one-off report that captures a snapshot in time, the interactive map and its accompanying database are designed to be regularly updated as new cases emerge. This ongoing nature is crucial because the phenomenon of punitive demolitions is itself ongoing. This makes the archive a living document of state actions. The importance of this cannot be overstated: patterns of repression can change over time, and a static report can quickly become outdated or incomplete.

Maintaining a live archive also means the project can capture nuances and new patterns as they develop. Authoritarian tactics evolve—for instance, if courts begin to clamp down on outright illegal demolitions, authorities might adapt by creating paper trails or new ordinances to justify them. The continuous documentation can catch such shifts: are states issuing new laws to legalise punitive demolitions? Are there changes in the official rationale given over time? The archive can be annotated with these details. Over the long term, this creates a robust historical record that can inform scholarly research and memory.

From data to narrative

While compiling data is essential, The Demolitions Project recognises that raw numbers alone cannot convey the human impact or political significance of state-led demolitions. One of the standout features of the project is its interactive map, which is far more than a spreadsheet of incidents—it is a storytelling platform. The map allows users to visualise the geographic spread and frequency of demolitions, offering an immediate sense of scope and pattern. With a quick glance, viewers can see clusters of demolition markers in certain states or regions, correlating with specific time periods or political regimes.

This visual aggregation helps transform abstract data into a tangible landscape of state violence. For instance, seeing multiple demolition sites dotting the map in Uttar Pradesh or Madhya Pradesh—states noted for frequent bulldozer actions—powerfully illustrates how normalised this practice has become in some areas. Such visualisation invites the public to engage with the data: one can zoom in on a city to find details of a particular case; use the filters to understand the frequency of different categories of demolitions; search for specific cases of demolitions by name; or scroll through time to watch the phenomenon unfold. In doing so, the project turns statistics into an interactive experience, making the reality of state excesses more accessible and harder to ignore.

Beyond the map’s pins and polygons, The Demolitions Project emphasises narrative and testimony, thereby turning data into compelling stories. Each demolition incident documented is accompanied by context – the official reason given, the timeline of events, and crucially in some cases, the voices and experiences of those directly affected. Through our Profiles of Demolitions, and the details, articles, and embedded media for the mapped incidents, the project highlights individual and community experiences behind each demolition.

This narrative-driven documentation brings forward the trauma and injustice in ways that pure data cannot capture. Our storytelling in documentation serves to bridge the emotional gap that often exists between human rights reports and public perception. By incorporating testimonies, photographs, and personal details, the demolitions map project invites empathy and public outrage, translating what might seem like dry facts into urgent moral questions. In a country as vast as India, it is easy for individual stories of injustice to get lost in the din; The Demolitions Project’s work ensures these stories are both heard and remembered, thereby making state violence visible and palpable to a wider audience.

Importantly, this interactive, narrative-based approach democratises information about state violence. The map presents information in a user-friendly format that journalists, students, activists, and ordinary citizens can all explore. It is akin to a public archive that one can walk through, case by case, story by story. By lowering the barriers to accessing detailed documentation, The Demolitions Project enables a broader segment of society to inform themselves about the realities of “bulldozer raj.”

In doing so, it cultivates a more informed public discourse. When people can point to a map and recount what happened to families in their own or neighboring towns, the issue of demolitions moves from the abstract realm of policy to the concrete realm of lived experience. This transformation of data into narrative is a powerful added value—it not only documents state violence but does so in a way that galvanises understanding and engagement.

Countering media and state narratives

One of the most significant added values lies in challenging and countering the dominant narratives presented by both the state and sections of the media. In many of the documented cases, the official line and its amplification in mainstream discourse followed a predictable pattern: authorities justify a demolition as a necessary action against “criminal elements,” “rioters,” or “anti-nationals,” and claim that the structures were illegal anyway. Large sections of the media then parrot these claims, framing the story as one of law and order, rather than as a human rights issue.

The very term “bulldozer justice,” which has gained currency, reflects this narrative of swift, no-nonsense action. In some TV studios and political rallies, the bulldozer is lionised as delivering instant justice that courts allegedly fail to provide. This discourse conveniently masks the reality of what these demolitions entail: innocent family members thrown on the street, livelihoods crushed, an endorsement of collective punishment, and entire communities terrorised without trial. By humanising the victims and meticulously documenting the facts, The Demolitions Project provides a powerful counter-narrative.

Through its map and associated stories, the project reframes the victims of demolitions as citizens with rights, rather than nameless wrongdoers. Each pin on the map is not just a structure; it represents people—often marginalised due to their religion—whose lives were upended. It shows that those affected are frequently ordinary law-abiding people who were caught in a wave of collective retribution. By presenting evidence from the ground, The Demolitions Project directly confronts this propaganda.

Moreover, The Demolitions Project’s narrative approach engages public empathy, which is crucial to countering state narratives that often dehumanise those affected. By reading the personal story of a family – their terror as the bulldozer arrived, their loss of heirlooms and documents in the rubble, the children’s trauma of seeing their home destroyed. The project brings forward a much-needed human rights perspective into public discourse. In a media environment where the voices of victims are seldom given equal platform as the voices of officials, this documentation elevates those suppressed voices. It brings forth the testimonies of people who ask the very simple question: “Sab kuch ek taraf, lekin aap kisi ka ghar kaise gira sakte hain?” (Setting aside everything, how can you demolish someone’s home?)

In doing so, it disrupts the state’s propaganda cycle. It becomes harder for authorities to paint a rosy picture of “justice served” when a well-documented counternarrative – complete with maps, data and human stories – is widely accessible, painting a very different picture of injustice and trauma inflicted.

Situating demolitions within a larger system of state violence

The Demolitions Project also situates these incidents within the broader architecture of state violence and authoritarian governance in India. This broader view is crucial: these demolitions are not random or apolitical; they often coincide with other forms of coercion such as police crackdowns, mass arrests, internet shutdowns, or discriminatory laws. By mapping demolitions alongside their causes, the project helps illustrate that the demolition of homes has become another weapon in the state’s arsenal—one that bypasses judicial processes, much like illegal detentions or extrajudicial encounters. In other words, home demolitions have become a visible symbol of a state machinery willing to dispense punishment outside the courtroom, reinforcing an overall climate of fear.

The project’s research and categorisation make clear that these demolitions are deeply enmeshed with Hindutva politics and social hierarchies. A striking pattern in the data is the disproportionate targeting of Muslim neighborhoods and properties, especially in BJP-ruled states. This mirrors the broader project of Hindu majoritarianism, where state violence often finds its justifications in demonising minority communities as threats.

Through its holistic approach, The Demolitions Project offers a framework for analysis: it encourages observers to examine not just the legal violation (demolition without due process) but the political logic behind these acts. The data can be used to ask questions like: are demolitions spiking around election times or major protests? Do they correlate with speeches by political leaders advocating “tough action”?

Preliminary analysis

Our current dataset reveals that the most frequently targeted category is that of individuals labelled as “Gangster/Mafia”—a classification applied broadly to politicians, businessmen, and associates of criminalised figures, particularly those from Muslim communities. Many of these demolitions are tied to high-profile figures such as Atiq Ahmed and Mukhtar Ansari, whose properties, as well as those of their relatives and associates, have been repeatedly razed. This reflects a broader strategy of punitive demolitions aimed at dismantling networks associated with figures deemed adversarial to the state.

Another significant category is “Political Opposition,” where demolitions have targeted opposition leaders and their families, particularly those affiliated with the Samajwadi Party and Bahujan Samaj Party. This suggests a pattern of using state machinery to suppress political dissent. Additionally, there are cases of demolitions categorised as “Post Riot” actions, where properties of individuals accused of participating in protests or communal disturbances were destroyed. Notably, several of these cases relate to protests against derogatory remarks about the Prophet Muhammad, indicating a punitive response to Muslim political expression.

Geographically, Prayagraj emerges as a focal point of the demolitions in Uttar Pradesh, with numerous actions taken against individuals linked to Atiq Ahmed. Other key locations include Lucknow, Kanpur, Saharanpur, and Mau. The timeline of these demolitions reveals that they intensified around politically sensitive moments, such as after protests or ahead of elections, further indicating a strategic use of demolition as a tool of state violence.

The data from Madhya Pradesh (MP) reveals a pattern of demolitions following communal violence, with the “Post Riot” category being the most frequent, accounting for six recorded instances. Other notable categories include “Crime and Punishment” and “Religious Targeting,” which suggest demolitions targeting individuals accused of criminal activities or belonging to specific religious groups. Interestingly, there is also an overlap in the two categories, reflecting how state narratives frame demolitions both as law enforcement and as communal actions.

Geographically, demolitions are scattered across multiple districts, with Ujjain, Dhar, Khargone, and Dewas among the affected areas. Notably, the demolitions in Khargone occurred across multiple localities, indicating a large-scale action, possibly targeting an entire community. Many of these demolitions seem to be responses to protests or unrest, aligning with broader state patterns of using bulldozers to collectively punish Muslim neighbourhoods in the wake of communal violence. These demolitions align with the broader Hindutva project of reconfiguring urban spaces to marginalise Muslim presence.

Limitations and Conclusion

While The Demolitions Project marks a critical intervention in tracking and analysing punitive demolitions in India, it is not without its limitations. The current scope of our documentation is geographically uneven, with a concentrated focus on states like Uttar Pradesh and Madhya Pradesh, where such demolitions have been highly visible and politically significant. While we are in the process of expanding our dataset to include additional regions such as Delhi and Haryana, other crucial states like Assam and Gujarat, where state-led demolition practices intersect with long-standing communal violence, remain outside the present scope of our research. This gap reflects both the challenges of access and the constraints of a small team working within a difficult and often hostile information environment.

Although we have aimed to document as many incidents as possible, this archive is not exhaustive. It is likely that some cases have gone unrecorded, either due to a lack of media coverage, suppressed local reporting, or the logistical and safety challenges of conducting fieldwork in certain regions. Additionally, while the Profiles of Demolitions series is central to our goal of centering survivor voices and contextualising the lived experience of state violence, such in-depth narrative accounts currently exist for only a subset of the demolitions we have recorded. The limitations here are both ethical and practical: interviews require trust, time, and care, and many families fear retaliation or are retraumatised by the act of retelling.

We remain committed to expanding this narrative layer of our documentation while upholding principles of consent, care, and dignity. Our work unfolds in a landscape where state repression, media complicity, and public desensitisation create formidable barriers to accountability. Despite these constraints, we believe the act of witnessing and recording itself is a form of resistance. These limitations are reminders of the urgency and complexity of the task at hand, and they mark areas where solidarity, collaboration, and continued research are most needed.

Rigorous documentation plays a pivotal role in resisting state violence and shaping the public discourse on issues of governance and justice. Through its semi-academic yet accessible approach, the project illuminates how punitive demolitions in India are not just about buildings being torn down, they are about the tearing apart of the rule of law and civil liberties. It recontextualises demolitions as part of a deliberate strategy of extrajudicial punishment and intimidation. This added framing is invaluable: it helps the public and policymakers alike to see the big picture of how seemingly local incidents connect to national patterns of authoritarian behavior.

The demolitions map’s blend of data and narrative has expanded the toolkit for accountability. It serves simultaneously as an archive of evidence, a platform for victim testimonials, and an analytical lens to view state actions. In the broader discourse on punitive demolitions and state violence, this work provides a reference point that did not exist before. Advocacy groups and legal activists would be able to invoke the patterns and cases highlighted by the project when arguing against the government’s heavy-handed tactics.

Crucially, The Demolitions Project underscores that memory is a form of resistance: by remembering and recording each demolition, it denies the state the power to erase these incidents from public consciousness. It tells the government that these acts are being watched, analysed, and will be recalled in history. It is through such collective efforts that we can hope to rein in punitive demolitions, restore adherence to due process, and hold the state accountable to the principles of justice and equality that are the bedrock of any democracy. It is, in effect, a bulwark defending the idea that no government can act with impunity when citizens wield the tools of truth and documentation.

SUPPORT US

We like bringing the stories that don’t get told to you. For that, we need your support. However small, we would appreciate it.