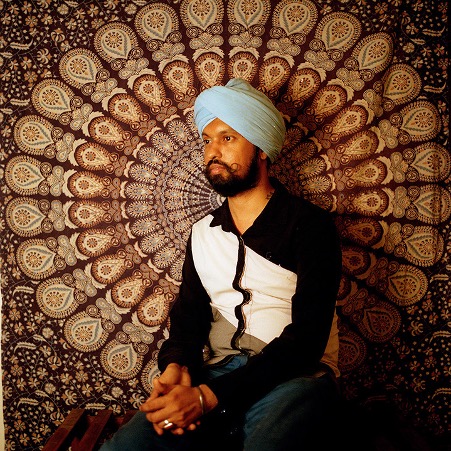

Naveen gestures as to ease the words out, while lining up the events of his life. As a kid he used to wear his mom and aunt’s sarees – he was fascinated by the bangles and the bindi on the forehead. At some point tough, his parents forbade him to dress up in girl’s clothes. He kept on doing it in secret, when he was home alone. He couldn’t avoid it. Naveen, now 25, says that his effeminate nature was the reason why he has always been bullied, humiliated and called names also from his teachers. His school years turned into a nightmare. “Back then I didn’t know I was gay: I only knew I was an effeminate guy and people made fun of me. I didn’t talk to anyone. I had no friends. I changed school, but it was all the same”, he says shooting his gaze somewhere above his head, looking for the right words. “I moved to Jaipur for my graduation, I wanted to leave everything behind and start a new chapter, but it was terrible. I lived in a hostel and there the bullying was 24/7. There were times I was fighting back and other times that I just wanted to take my life. I never thought about suicide, but they pushed me to consider it.” When he became aware of being homosexual, he didn’t explore his sexuality out of fear he would be further bullied.

Internet, technology and a wider community of people sharing similar experiences became his shelter from the outside world and gave him the courage to hang on. Naveen went for counselling and started instead considering his strengths. Despite the difficulties, he pursued his studies and eventually became a teacher – his childhood’s dream. Internet, technology and a wider community of people sharing similar experiences became his shelter from the outside world and gave him the courage to hang on. When he tried to come out to his family, he got bashed. They shouted at him saying that he was shaming the family, that he was a “sinner”. Nevertheless, he kept on exploring his identity and sexuality, pushing the walls he always felt growing around him. A few years ago, some friends decided to shoot a movie about his life that was screened at the 2016 Delhi International Queer Theater and Film Festival. “When they called me on stage I was crying,” he says with a shy smile. He cried during the whole screening as he saw his life rolling in front of his eyes and the audience. “People called me brave, but I’m not brave,” he argues. “Only when my family will change their mentality and accept me, I will be brave. These people were supporting me, and this simple fact made me feel relieved.” Now, beside teaching in school, he runs Miss Woomaniya Production with a group of friends: their work aims at spreading awareness and educating the society on LGBTQ issues through movies, videos and interviews. He never got support from his family or siblings: when his family found out about the movie, he got beaten black and blue.

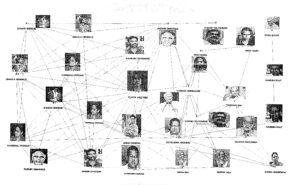

A generation that has pushed the walls of traditional and patriarchal Indian society by challenging its heteronormativity and binary structure. Social media and internet have played a great role in creating a safe space (although virtual): a transversal network of individuals sharing similar issues and experiences. Naveen belongs to a generation of Indian urban millennials identifying as queer – an umbrella term that embraces the whole LGBTQIA+ (acronym for lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans, queer, intersex, a-sexual) spectrum – that has grown up under a colonial law criminalizing their sexual orientation. A generation that has pushed the walls of traditional and patriarchal Indian society by challenging its heteronormativity and binary structure. Social media and internet have played a great role in creating a safe space (although virtual): a transversal network of individuals sharing similar issues and experiences. The ban on homosexual intercourse in the years of digital connectivity triggered the spread of a number of chats, platforms and online dating apps that came to a lifeline in countries where being gay was (or is) illegal. Bucking the trend of other Southeast Asian countries such as Bangladesh, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Malaysia, Indonesia, Brunei or Myanmar, on 6 September 2018 the Indian Supreme Court, after a long legal battle, has finally decriminalized homosexual activities among consenting adults.

Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code, a law dated 1861, prescribed prison sentences up to ten years for activities “against the order of nature” – meaning homosexual intercourses – that were likened to zoophilia and paedophilia, and resulted in years of intimidation, blackmail and abuse from the police or even in the private sphere, like from landlords towards an entire community, especially its weakest segments. The abrogation of the British era law in the Commonwealth’s largest country spread hope also in other former British colonies, where draconian laws against homosexuality are still in force.

In a vast country like India, marked by enormous diversities, the attitudes towards LGBT issues and the experiences of individuals identifying in the LGBT spectrum may vary a lot from region to region. The gap between urban and rural reality, and the differences based on language, caste, class and gender, add further layers and complexities to the topic. “Despite the recent decriminalization of homosexuality, India is still a tough place to be queer, homophobia and transphobia are imbued in our patriarchal society. We just want a place in the society, to feel citizens like the others”, argues Prateek, 25, AKA Betta Naan Stop, a gay dancer who performs as a drag queen all over India. He was recently featured on the cover of Vogue India with his distinctive blonde wig and a glittering golden dress. “Some people think that being gay is not part of our culture, they blame Western influences, but homosexuality has always been there, also in ancient India, it’s part of life,” he adds. “But it’s a taboo here, so it’s sex, there is no talk about it in the society.” In a vast country like India, marked by enormous diversities, the attitudes towards LGBT issues and the experiences of individuals identifying in the LGBT spectrum may vary a lot from region to region. The gap between urban and rural reality, and the differences based on language, caste, class and gender, add further layers and complexities to the topic, according to Zainab Patel, a transgender activist who has worked with United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and was among the petitioners in the National Legal Services Authority (NALSA) vs. Union of India case, better known as the NALSA judgement, a landmark judgement in the protection of transgender rights that reflects similar legislations in force in Nepal, Pakistan and Bangladesh.

These events became like a platform where people got together to oppose every form of violence that the patriarchal society forces upon people who challenge socially constructed norms on gender and sexuality. Propelled by the HIV/AIDS epidemic, India witnessed its first gay-rights protest in the early 90s. The first Pride was held in 1999 in Kolkata, when the Friendship Walk, with an attendance of barely 15 people who took to the streets made history also as South Asia’s first event of its kind. Far from the glitters of today’s prides, the walk did set an enormous milestone in the region. But it’s only in early 2000s that the movement got momentum in India. People and activists started to publicly raise their voice against the criminalization of their sexual orientation and demanded for the abrogation of anti-homosexual laws. The “walks” slowly spread to other big cities and, later on, at a different scale, they also reached smaller ones. These events became like a platform where people got together to oppose every form of violence that the patriarchal society forces upon people who challenge socially constructed norms on gender and sexuality. In 2008, for the first time, coordinated walks were held in four cities: New Delhi, Bangalore, Pondicherry and Calcutta. The movement became more and more like a network spanning among different cities, communities and groups.

The long and strenuous legal battle for the abrogation of Section 377 ended with a verdict that finally struck down much of the section as unconstitutional, rendering homosexuality no longer a crime in India. It was 2 July 2009, a historic moment for the country and its queer community. Treating the relation between adults of the same sex as a crime, is a violation of the fundamental rights granted by the Indian Constitution this was the main point of the petition filed by the NGO Naz Foundation to the Delhi High Court in 2001. The long and strenuous legal battle for the abrogation of Section 377 ended with a verdict that finally struck down much of the section as unconstitutional, rendering homosexuality no longer a crime in India. It was 2 July 2009, a historic moment for the country and its queer community. The joy brought by this huge victory was however soon to be overshadowed. The decision was in fact overturned by a Supreme Court ruling in 2013 – following appeals filed by religious organizations – that reinstated the ban, until the epilogue dated September 2018, which put an end to a 17-years long legal battle. “While in a narrow sense today’s judgment is about Section 377, it is so much more than that. Like the LGBT movement in India, this case was borne out of the need to address everyday structural and endemic forms of violence”, wrote Mayur Suresh, lecturer in Law at the SOAS in London, in an article on The Guardian when the homosexuality was finally rendered legal in India.

The 2019 Pride, rather than a walk, turned into a peaceful protest in many Indian cities. The community came together to raise its voice against the Transgender Persons (Protection of Rights) Bill 2019, a law that, according to activists, is actually promoting transphobia and stigmatization and has been rejected by the very people it claims to protect. “The bill goes against the core principle of the Supreme Court’s judgement, which accords citizens the right to identify as male, female or transgender, irrespective of gender affirming surgeries or hormonal therapy,” explains Zainab Patel. “When the bill was first introduced there was a lot uproar over the fact that they tried to medicalize the entire gender transition, while the bill was meant to protect the trans community and the right to self-identification.”

In the 2014 NALSA judgement, the Supreme Court had in fact affirmed that the fundamental rights granted under the Constitution will be equally applicable to transgender people and gave them the right to self-determinate their own gender while it also prescribed affirmative action to address economic inequalities. In 2017, the Court also ruled that the individual privacy is a fundamental right and that “sexual orientation is an essential attribute of privacy.” Yet, under the new Bill, a two-step process has been introduced: a person has to first get a certificate from a local government official proving one’s identity as transgender. Then, to identify as male or female, a transgender person has to undergo surgery and then have the certificate revised from the magistrate. “I feel that instead of promoting our rights and entitlements, the government has taken away our right to self-identification,” comments Zainab. Under the new provisions, surgery seems to become mandatory to be identified according to one’s gender.

Access is more difficult for trans men from Dalit and Adivasi backgrounds, who neither have access to these virtual groups nor financial stability. But, in some instances, we have been able to fund raise and support many people who could otherwise not afford these procedures. I met Gee in a Delhi park on a warm April day. He is a 32-year-old trans man activist from the southern state of Kerala, who speaks about his journey with incredible strength. “There is no particular moment that you can point out, transitioning is rather a process. Studies show have a sense of gender by the age of 5, even 3 sometimes,” he says while sitting on a bench in the afternoon light. He recalls how during his puberty he failed at performing the “femininity the society was expecting from him.” Like many people, at the beginning he thought that he was homosexual. Gee was very open about it and he was made to feel that he was “betraying the feminism he believed in, by going to the oppressor’s side.” There was a lot of transphobia among gay and lesbian circles at the time, he says. He was brought up by a single mother who knew everything before Gee even told her. He recalls how, before the internet, information on transition, sex reassignment surgery (SRS) and name changing were more difficult to come by. “Now it’s all on the internet and WhatsApp groups. I remember how my trans partner and I went all over India by train to map where the doctors for SRS were. We put out the information [on trans forums], so a lot of guys could access surgery. Access is more difficult for trans men from Dalit and Adivasi backgrounds, who neither have access to these virtual groups nor financial stability. But, in some instances, we have been able to fund raise and support many people who could otherwise not afford these procedures. I went to do mine in Mumbai, but it was botched,” he says. “I underwent two surgeries in Mumbai. I felt suicidal because you wait for this moment all your life and then things go wrong. It was a case of medical negligence. The doctor had no expertise and wanted to make money off us and she did this to many other trans men too. My mum and my partner were very supportive and took care of me and I came back to life.” Gee finally got his third surgery done in the US. “This is the state of trans health system in India,” he comments. “There is a lot of rumor in the media about funds available from the government but, except for Kerala, it’s not true. Nothing is available, even doctors are exploiting the situation by charging ridicule prices for very poorly done surgeries.”

“When I first started hormones, no doctors would prescribe them in the city I was in, so I was self-injecting. I spoke to other brothers abroad and got information on YouTube. It is pretty easy to inject although I was very bad at it and I have a lot of scars from that time. After some years I finally found a doctor who would prescribe the therapy,” he recalls. “Then I had to get the certificate for ‘gender disorder’, because in the medical frame you are always victimized and pathologized as if you have some abnormality. ‘I feel suicidal, I am depressed cause I don’t belong to this body, I have gender dysphoria’ – these are all the things psychiatrists wanted to hear from me. Finally I could get my surgery done.” Gender dysphoria is the distress a person feels due to a mismatch between their gender identity and their sex assigned at birth. The label gender identity disorder was officially renamed gender dysphoria in 2013 in an attempt to remove the stigma associated with the term disorder. “I am still excluded in my family, from photos for example. They can’t explain who this new guy in the family is so, you see, it’s a collective process: it’s not just about you, your family has to transition with you too. My mother has been a rock, and I am alive because of her. I avoid confessional narratives of trauma and this often disappoints journalists who look for such stories,” he says with lively eyes. He has settled in Bangalore now where there is a very strong community of trans men. “We are a big family, which is very important for transgender people who lose their biological family. Chosen families are the way in which we survive, the hijra family structure has existed for many centuries. Despite hierarchies within, we need a family to survive, and this is the only system that works to whatever extent possible given the circumstances.”

Historians blame the British, with their bigotry and morality, for having tried to erase the “third gender” by imposing the criminalization of homosexuality and the marginalization of an ancient subculture like the hijras. Others point the finger against the caste system, the transphobia and prejudices of India’s patriarchal society, that added to the ostracization of gender non-conforming people. This resulted in an ambivalent approach with which the society treats this traditional cultural identity, yet the long-lasting criminalization of the entire community contributed to widespread abuses, violence and marginalization. Many hijras live in groups, under the leadership of an elder member called guru, a mother-like figure. Nisha, 26, hails from Malda, a small town in West Bengal and since the age of five has been living in a family of hijras, a term used to identify a community of gender non-conforming people who may include transgender people, non-binary gender and intersex individuals alike. Given the special place hijras enjoyed in Hindu tradition and Indian history, they used to be treated with reverence and respect in ancient times. Historians blame the British, with their bigotry and morality, for having tried to erase the “third gender” by imposing the criminalization of homosexuality and the marginalization of an ancient subculture like the hijras. Others point the finger against the caste system, the transphobia and prejudices of India’s patriarchal society, that added to the ostracization of gender non-conforming people. This resulted in an ambivalent approach with which the society treats this traditional cultural identity, yet the long-lasting criminalization of the entire community contributed to widespread abuses, violence and marginalization many hijras live in groups, under the leadership of an elder member called guru, a mother-like figure. Violence, lack of education (school dropouts are very common among trans people) and access to formal employment are stringent issues, both in rural and urban contexts. Away from courts and royal palaces where they used to have a “role”, in modern times this traditional cultural identity, faced with the endemic discriminatory structure of the Indian society and its hierarchical social division, was left with little space to survive. Besides some exceptions, begging and prostitution are the few available livelihoods for hijras. This is the case of Nisha, born in a poor family who “noticed her being different” as she was a toddler. A guru has taken care of her since she was a kid. She has never attended school nor is she familiar with the solidarity networks outside the hierarchy of her chosen family. “The amount of pain and suffering we go through is so much. We have nothing to look forward to. People harass us on the streets and everywhere we go, they even beat us. I have no will to live for long,” she says in a whisper.

“We are under gurus who check on our behavior so as not to put the community in a bad light. It’s a family, someone who is responsible for you,” tells me Rudrani, 40, a brilliant exception of a trans woman activist, model and actor, who is the founder and director of Mitr Trust, an organization that works on HIV/AIDS prevention. “It’s a system, if your family disowns you where do you go? Gurus are shelters, anchors, they protect us, groom us and teach us survival. They are teachers, parents and mentors.” Activists have opposed the Bill for forcibly trying to rehabilitate trans people with their biological families or shelter homes, for criminalizing the community for begging but it’s being silent on the issue of reservation in jobs and education, while watering down criminal provisions and laws for hate crimes and assaults on trans persons. The punishment for sexual violence against a transgender person is in fact substantially lower than that for rape and sexual assault against women (a maximum of 2 years compared to 7 for women). “The Bill doesn’t give any provision about the rampant issue of sexual violence. Rape and assaults of trans people are happening with an alarming frequency in India, but we don’t get enough media attention,” denounces Zainab. Despite the numerous recommendations deposed by trans groups, experts and legal advocacy groups to the Parliamentary Standing Committee, the Bill is regressive and presents a series of criticalities yet it contains a better description of transgender person than the one contained in the previous draft, which opened with a disturbing definition: “neither wholly female nor wholly male; or a combination of female or male; or neither female nor male.” A description that seems to describe intersex individuals rather than trans, and probably derives from the mythical figure of the Hindu god Ardhanarishvara, a form of the god Shiva composed of a half-male and half-female body. “The new Bill has finally adopted the definition of transgender persons as per the NALSA judgement. Yet, the problem is not the definition, but the provisions,” points out Zainab, “hijras in India are cut out of mainstream education and jobs, yet when it comes to addressing economic inequalities the government has no road map”. State and central governments have in fact disregarded the recommendations of the Supreme Court to extend reservation in education and employment to the transgender community. “This Bill makes a mockery of my personhood and will only add to everyday humiliation and violations”, she adds.

“I learned about intersexuality at the age of 22. But even before that I knew that I was different, that my body was different,” explains Chinju, 25, a Dalit and trans rights activist from Kerala. It’s when he attended a gender and sexuality workshop organized by a Dalit feminist group that he learned that “hermaphrodite” is the name doctors use when a person is born with a combination of male and female biological traits – the term is no longer in use, the correct one is intersex. He learned that the word is an umbrella term, like trans, which includes many variations. He cried after this eye-opening workshop. “I’m the only intersex person in Kerala to be out, but in India we are many,” he says. According to experts, around 1.7 per cent of the world population is born with intersex traits, yet people with these variations face stigmatization and discrimination, including infanticide, abandonment, abuse and corrective surgeries at early age. “My parents brought me up as a girl. They showed me to many doctors. At that time, they all suggested a corrective surgery. Only one doctor advised them to postpone it until I would be old enough to decide. I was lucky, my parents listened to him and when I turned 16 we consulted a surgeon, but I wanted to continue my studies. I knew I would have had problems if I had changed gender on my IDs” he says. “People asked many intrusive and inappropriate questions about my sexuality, my body. Often, I have no answers because I do not fit into their narrow binary mindset. When people bullied me, I started fighting back, I became very bold and handled many situations. At 22 I joined the queer movement.” Chinju, who has participated in Lok Sabha election 2019 from Kerala, has ever since been a very vocal LGBT and Dalit’s rights activist and has engaged in grassroots work advocating for an intersectional understanding of marginalities.

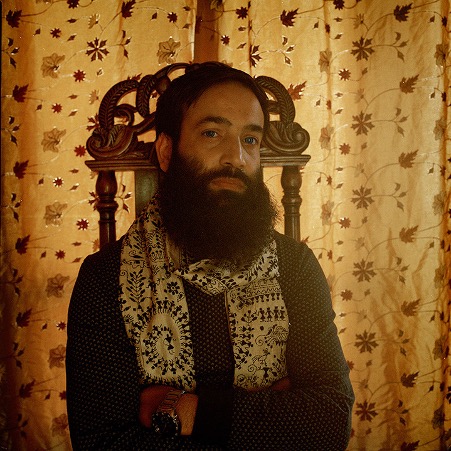

Discrimination is often the result of multiple and overlapping levels of oppression based on caste, sex, religion, language, and geography. According to feminist and Dalit scholars who acknowledge that gender identity and sexual orientation are not the only forms of selfhood and that people have multiple identities – it is important to look at gender issues and related violence in India (but not only) through the lens of intersectionality. Discrimination is often the result of multiple and overlapping levels of oppression based on caste, sex, religion, language, and geography. Aijaz is a social worker and LGBT ally and activist from Kashmir, where Indian forces de facto occupation in the region that resulted in widespread tortures, abuses, forced disappearing and extrajudicial killings. The 30-year-long occupation, who had, and still has, a great impact on civilians, was coronated last August when the Indian government stripped Kashmir of its autonomous status. The annexation of Kashmir and the military siege imposed in the region was accompanied by the longest internet shut down in history (140 days) whereas its main city, Srinagar, is considered the internet shut down capital of the world. “In Kashmir we have to maintain a very low profile because of the conflict, because of religious extremism,” argues Aijaz, “We have many layers of oppression here: the community, the Muslim identity and then the conflict, the caste system, the gender.” All these structural identities play a big role in the construction of a person: intersectionality studies show how interlocking systems of power and oppression affect the marginalized groups.

I realized I am not alone and there are so many more people like me, living freely. It was like a revelation. I felt the whole world into myself. R. is a 28-year-old lesbian-identifying Kashmiri girl who asked for her portrait not to show her face and name. “My family doesn’t know about me, very few people know who I am, what I do. I was never attracted to boys; I was never fitting to the image of a usual girl. Finally, in my college days I was exposed to more information and I came to know about the word ‘lesbian’. Reading a novel, I found this term, but I couldn’t find any reference to it in Kashmiri language. On the internet I finally read about people like myself, I had a definition for who I was. I realized I am not alone and there are so many more people like me, living freely. It was like a revelation. I felt the whole world into myself. I once talked to my siblings and their view was totally patriarchal and dogmatic, religion-biased and old-minded. ‘This is sin, you talk rubbish,’ they told me. Even my smaller brother judges me. My family makes me feel guilty, just the word lesbian makes them shiver,” she says staring the floor. “They would prefer to kill me [rather than accept my sexuality]. Here honor killings are not denounced, they don’t get called with their name. Some murders are portrayed as suicide. I fear for my life and I am dying a slow death”. Family support, or at least a non-hostile environment, can be big game-changers in the life of a queer person: acceptance is often a key factor in the well-being, resilience and self-esteem of young adults, who are forced to fight enormous battles to explore, and then affirm, their sexual or gender identity.

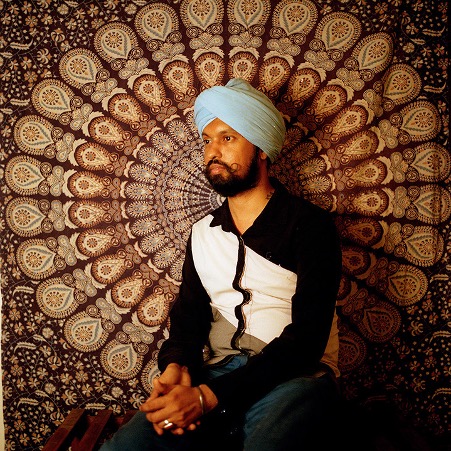

“In India we cannot understand queerness if we do not understand caste,” asserts Dhrubo Jyoti, 29, a Dalit and genderqueer journalist writing about gender, caste and sexuality. “Many members of what we call LGBT community are not just queer, but are also low caste, or Muslim, or Adivasi. They are already a minority. Or think about women. We know that lesbians and trans women face far more resistance and discrimination than gay men do. Also, in cities like Delhi women face alienation and discrimination even in queer spaces. So, we cannot understand LGBT issues if we don’t understand first the kind of oppression that comes from caste, gender and religion. We cannot think about a single, unified LGBT movement.” Indeed, many people reproach the movement for still not being fully inclusive and being divided into factions that cut across different lines based on class, caste, religion, rural/urban divide, education and gender. “In India the movement is multi-layered. Of course, it’s gay men who dominate the LGBT community: lesbian women, for example, they have this pressure, because we live in a patriarchal society, it’s difficult to be a woman in India. Many lesbians are not out because it’s more difficult for them. It’s definitely harder for women, as gay men we still have some privileges,” claims Sukhdeep, a gay-identifying IT professional, founder and editor of Gaylaxy, an online magazine on LGBT issues. When he first started publishing the magazine in 2010, he got an incredible response. “So many people in hetero relations, wrote about their personal stories and need to come out. The posts have been a source of hope for many people who feel alone in rural India, in oppressive families or in less open places than metro cities. Social media is the prime resource for queer people. For a very long time I was only connected to the community in virtual life. Forums help people feel more comfortable and give inspiration to come out,” he says.

]That the movement is divided and somehow crossed by different lines is in a way no surprise given the country’s variegated social fabric and profound divisions. Yet, it has achieved a lot in these twenty years thanks to the boldness of many people and it has succeeded in creating (virtually and physically) a space for queer individuals to come together and claim their role in society amidst the challenges, abuses and prejudices they face daily. “Yet now it’s not only about pride marches in India but the movement has further expanded creating other events like queer film festivals in Mumbai, Bangalore , Chennai and, from last year, also Queer literature festival. It started in Chennai, then Lucknow and this year Delhi also had one. “There were not only LGBT individuals attending the Rainbow Lit Festivalin Delhi but also many non-queer people from the civil society. It’s a very radical change and a very recent phenomenon,” asserts Sukhdeep.

That the society at large is opening up and becoming more inclusive is particularly true in big cities where diverse interactions as well as the urban anonymity leave far greater space for self-determination and identity building, of which sexual orientation and gender identity are fundamental parts. A generation of bold queer individuals who have pushed the walls around them breaking the gospel of patriarchal families and traditional structures. Despite all these breakthroughs, the way is still long to the full acceptance by the larger society and the recognition of the community’ rights, not least because of regressive laws such as the Trans Bill. Or the National Register of Citizens piloted in Assam: an exclusionary exercise to weed out “undocumented migrants” of Bangladeshi origin, planned to be extended to the rest of India. The mass census in Assam has turned out excluding almost 2 million people and, among them, many individuals from the trans community whose documentation is hardly consistent in terms of name and, hence, descent. When Section 377 was read down lifting the ban on homosexuality in India, Justice Indu Malhotra used these words: “History owes an apology to the members of this community and their families for the ignominy and ostracism that they have suffered through the centuries. The members of this community were compelled to live a life full of fear of reprisal and persecution”. An apology that is yet to fully come.

Related Posts

Young, bold and queer: India’s LGBTQIA+ young generation fighting for their rights

Naveen gestures as to ease the words out, while lining up the events of his life. As a kid he used to wear his mom and aunt’s sarees – he was fascinated by the bangles and the bindi on the forehead. At some point tough, his parents forbade him to dress up in girl’s clothes. He kept on doing it in secret, when he was home alone. He couldn’t avoid it. Naveen, now 25, says that his effeminate nature was the reason why he has always been bullied, humiliated and called names also from his teachers. His school years turned into a nightmare. “Back then I didn’t know I was gay: I only knew I was an effeminate guy and people made fun of me. I didn’t talk to anyone. I had no friends. I changed school, but it was all the same”, he says shooting his gaze somewhere above his head, looking for the right words. “I moved to Jaipur for my graduation, I wanted to leave everything behind and start a new chapter, but it was terrible. I lived in a hostel and there the bullying was 24/7. There were times I was fighting back and other times that I just wanted to take my life. I never thought about suicide, but they pushed me to consider it.” When he became aware of being homosexual, he didn’t explore his sexuality out of fear he would be further bullied.

Internet, technology and a wider community of people sharing similar experiences became his shelter from the outside world and gave him the courage to hang on. Naveen went for counselling and started instead considering his strengths. Despite the difficulties, he pursued his studies and eventually became a teacher – his childhood’s dream. Internet, technology and a wider community of people sharing similar experiences became his shelter from the outside world and gave him the courage to hang on. When he tried to come out to his family, he got bashed. They shouted at him saying that he was shaming the family, that he was a “sinner”. Nevertheless, he kept on exploring his identity and sexuality, pushing the walls he always felt growing around him. A few years ago, some friends decided to shoot a movie about his life that was screened at the 2016 Delhi International Queer Theater and Film Festival. “When they called me on stage I was crying,” he says with a shy smile. He cried during the whole screening as he saw his life rolling in front of his eyes and the audience. “People called me brave, but I’m not brave,” he argues. “Only when my family will change their mentality and accept me, I will be brave. These people were supporting me, and this simple fact made me feel relieved.” Now, beside teaching in school, he runs Miss Woomaniya Production with a group of friends: their work aims at spreading awareness and educating the society on LGBTQ issues through movies, videos and interviews. He never got support from his family or siblings: when his family found out about the movie, he got beaten black and blue.

A generation that has pushed the walls of traditional and patriarchal Indian society by challenging its heteronormativity and binary structure. Social media and internet have played a great role in creating a safe space (although virtual): a transversal network of individuals sharing similar issues and experiences. Naveen belongs to a generation of Indian urban millennials identifying as queer – an umbrella term that embraces the whole LGBTQIA+ (acronym for lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans, queer, intersex, a-sexual) spectrum – that has grown up under a colonial law criminalizing their sexual orientation. A generation that has pushed the walls of traditional and patriarchal Indian society by challenging its heteronormativity and binary structure. Social media and internet have played a great role in creating a safe space (although virtual): a transversal network of individuals sharing similar issues and experiences. The ban on homosexual intercourse in the years of digital connectivity triggered the spread of a number of chats, platforms and online dating apps that came to a lifeline in countries where being gay was (or is) illegal. Bucking the trend of other Southeast Asian countries such as Bangladesh, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Malaysia, Indonesia, Brunei or Myanmar, on 6 September 2018 the Indian Supreme Court, after a long legal battle, has finally decriminalized homosexual activities among consenting adults.

Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code, a law dated 1861, prescribed prison sentences up to ten years for activities “against the order of nature” – meaning homosexual intercourses – that were likened to zoophilia and paedophilia, and resulted in years of intimidation, blackmail and abuse from the police or even in the private sphere, like from landlords towards an entire community, especially its weakest segments. The abrogation of the British era law in the Commonwealth’s largest country spread hope also in other former British colonies, where draconian laws against homosexuality are still in force.

In a vast country like India, marked by enormous diversities, the attitudes towards LGBT issues and the experiences of individuals identifying in the LGBT spectrum may vary a lot from region to region. The gap between urban and rural reality, and the differences based on language, caste, class and gender, add further layers and complexities to the topic. “Despite the recent decriminalization of homosexuality, India is still a tough place to be queer, homophobia and transphobia are imbued in our patriarchal society. We just want a place in the society, to feel citizens like the others”, argues Prateek, 25, AKA Betta Naan Stop, a gay dancer who performs as a drag queen all over India. He was recently featured on the cover of Vogue India with his distinctive blonde wig and a glittering golden dress. “Some people think that being gay is not part of our culture, they blame Western influences, but homosexuality has always been there, also in ancient India, it’s part of life,” he adds. “But it’s a taboo here, so it’s sex, there is no talk about it in the society.” In a vast country like India, marked by enormous diversities, the attitudes towards LGBT issues and the experiences of individuals identifying in the LGBT spectrum may vary a lot from region to region. The gap between urban and rural reality, and the differences based on language, caste, class and gender, add further layers and complexities to the topic, according to Zainab Patel, a transgender activist who has worked with United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and was among the petitioners in the National Legal Services Authority (NALSA) vs. Union of India case, better known as the NALSA judgement, a landmark judgement in the protection of transgender rights that reflects similar legislations in force in Nepal, Pakistan and Bangladesh.

These events became like a platform where people got together to oppose every form of violence that the patriarchal society forces upon people who challenge socially constructed norms on gender and sexuality. Propelled by the HIV/AIDS epidemic, India witnessed its first gay-rights protest in the early 90s. The first Pride was held in 1999 in Kolkata, when the Friendship Walk, with an attendance of barely 15 people who took to the streets made history also as South Asia’s first event of its kind. Far from the glitters of today’s prides, the walk did set an enormous milestone in the region. But it’s only in early 2000s that the movement got momentum in India. People and activists started to publicly raise their voice against the criminalization of their sexual orientation and demanded for the abrogation of anti-homosexual laws. The “walks” slowly spread to other big cities and, later on, at a different scale, they also reached smaller ones. These events became like a platform where people got together to oppose every form of violence that the patriarchal society forces upon people who challenge socially constructed norms on gender and sexuality. In 2008, for the first time, coordinated walks were held in four cities: New Delhi, Bangalore, Pondicherry and Calcutta. The movement became more and more like a network spanning among different cities, communities and groups.

The long and strenuous legal battle for the abrogation of Section 377 ended with a verdict that finally struck down much of the section as unconstitutional, rendering homosexuality no longer a crime in India. It was 2 July 2009, a historic moment for the country and its queer community. Treating the relation between adults of the same sex as a crime, is a violation of the fundamental rights granted by the Indian Constitution this was the main point of the petition filed by the NGO Naz Foundation to the Delhi High Court in 2001. The long and strenuous legal battle for the abrogation of Section 377 ended with a verdict that finally struck down much of the section as unconstitutional, rendering homosexuality no longer a crime in India. It was 2 July 2009, a historic moment for the country and its queer community. The joy brought by this huge victory was however soon to be overshadowed. The decision was in fact overturned by a Supreme Court ruling in 2013 – following appeals filed by religious organizations – that reinstated the ban, until the epilogue dated September 2018, which put an end to a 17-years long legal battle. “While in a narrow sense today’s judgment is about Section 377, it is so much more than that. Like the LGBT movement in India, this case was borne out of the need to address everyday structural and endemic forms of violence”, wrote Mayur Suresh, lecturer in Law at the SOAS in London, in an article on The Guardian when the homosexuality was finally rendered legal in India.

The 2019 Pride, rather than a walk, turned into a peaceful protest in many Indian cities. The community came together to raise its voice against the Transgender Persons (Protection of Rights) Bill 2019, a law that, according to activists, is actually promoting transphobia and stigmatization and has been rejected by the very people it claims to protect. “The bill goes against the core principle of the Supreme Court’s judgement, which accords citizens the right to identify as male, female or transgender, irrespective of gender affirming surgeries or hormonal therapy,” explains Zainab Patel. “When the bill was first introduced there was a lot uproar over the fact that they tried to medicalize the entire gender transition, while the bill was meant to protect the trans community and the right to self-identification.”

In the 2014 NALSA judgement, the Supreme Court had in fact affirmed that the fundamental rights granted under the Constitution will be equally applicable to transgender people and gave them the right to self-determinate their own gender while it also prescribed affirmative action to address economic inequalities. In 2017, the Court also ruled that the individual privacy is a fundamental right and that “sexual orientation is an essential attribute of privacy.” Yet, under the new Bill, a two-step process has been introduced: a person has to first get a certificate from a local government official proving one’s identity as transgender. Then, to identify as male or female, a transgender person has to undergo surgery and then have the certificate revised from the magistrate. “I feel that instead of promoting our rights and entitlements, the government has taken away our right to self-identification,” comments Zainab. Under the new provisions, surgery seems to become mandatory to be identified according to one’s gender.

Access is more difficult for trans men from Dalit and Adivasi backgrounds, who neither have access to these virtual groups nor financial stability. But, in some instances, we have been able to fund raise and support many people who could otherwise not afford these procedures. I met Gee in a Delhi park on a warm April day. He is a 32-year-old trans man activist from the southern state of Kerala, who speaks about his journey with incredible strength. “There is no particular moment that you can point out, transitioning is rather a process. Studies show have a sense of gender by the age of 5, even 3 sometimes,” he says while sitting on a bench in the afternoon light. He recalls how during his puberty he failed at performing the “femininity the society was expecting from him.” Like many people, at the beginning he thought that he was homosexual. Gee was very open about it and he was made to feel that he was “betraying the feminism he believed in, by going to the oppressor’s side.” There was a lot of transphobia among gay and lesbian circles at the time, he says. He was brought up by a single mother who knew everything before Gee even told her. He recalls how, before the internet, information on transition, sex reassignment surgery (SRS) and name changing were more difficult to come by. “Now it’s all on the internet and WhatsApp groups. I remember how my trans partner and I went all over India by train to map where the doctors for SRS were. We put out the information [on trans forums], so a lot of guys could access surgery. Access is more difficult for trans men from Dalit and Adivasi backgrounds, who neither have access to these virtual groups nor financial stability. But, in some instances, we have been able to fund raise and support many people who could otherwise not afford these procedures. I went to do mine in Mumbai, but it was botched,” he says. “I underwent two surgeries in Mumbai. I felt suicidal because you wait for this moment all your life and then things go wrong. It was a case of medical negligence. The doctor had no expertise and wanted to make money off us and she did this to many other trans men too. My mum and my partner were very supportive and took care of me and I came back to life.” Gee finally got his third surgery done in the US. “This is the state of trans health system in India,” he comments. “There is a lot of rumor in the media about funds available from the government but, except for Kerala, it’s not true. Nothing is available, even doctors are exploiting the situation by charging ridicule prices for very poorly done surgeries.”

“When I first started hormones, no doctors would prescribe them in the city I was in, so I was self-injecting. I spoke to other brothers abroad and got information on YouTube. It is pretty easy to inject although I was very bad at it and I have a lot of scars from that time. After some years I finally found a doctor who would prescribe the therapy,” he recalls. “Then I had to get the certificate for ‘gender disorder’, because in the medical frame you are always victimized and pathologized as if you have some abnormality. ‘I feel suicidal, I am depressed cause I don’t belong to this body, I have gender dysphoria’ – these are all the things psychiatrists wanted to hear from me. Finally I could get my surgery done.” Gender dysphoria is the distress a person feels due to a mismatch between their gender identity and their sex assigned at birth. The label gender identity disorder was officially renamed gender dysphoria in 2013 in an attempt to remove the stigma associated with the term disorder. “I am still excluded in my family, from photos for example. They can’t explain who this new guy in the family is so, you see, it’s a collective process: it’s not just about you, your family has to transition with you too. My mother has been a rock, and I am alive because of her. I avoid confessional narratives of trauma and this often disappoints journalists who look for such stories,” he says with lively eyes. He has settled in Bangalore now where there is a very strong community of trans men. “We are a big family, which is very important for transgender people who lose their biological family. Chosen families are the way in which we survive, the hijra family structure has existed for many centuries. Despite hierarchies within, we need a family to survive, and this is the only system that works to whatever extent possible given the circumstances.”

Historians blame the British, with their bigotry and morality, for having tried to erase the “third gender” by imposing the criminalization of homosexuality and the marginalization of an ancient subculture like the hijras. Others point the finger against the caste system, the transphobia and prejudices of India’s patriarchal society, that added to the ostracization of gender non-conforming people. This resulted in an ambivalent approach with which the society treats this traditional cultural identity, yet the long-lasting criminalization of the entire community contributed to widespread abuses, violence and marginalization. Many hijras live in groups, under the leadership of an elder member called guru, a mother-like figure. Nisha, 26, hails from Malda, a small town in West Bengal and since the age of five has been living in a family of hijras, a term used to identify a community of gender non-conforming people who may include transgender people, non-binary gender and intersex individuals alike. Given the special place hijras enjoyed in Hindu tradition and Indian history, they used to be treated with reverence and respect in ancient times. Historians blame the British, with their bigotry and morality, for having tried to erase the “third gender” by imposing the criminalization of homosexuality and the marginalization of an ancient subculture like the hijras. Others point the finger against the caste system, the transphobia and prejudices of India’s patriarchal society, that added to the ostracization of gender non-conforming people. This resulted in an ambivalent approach with which the society treats this traditional cultural identity, yet the long-lasting criminalization of the entire community contributed to widespread abuses, violence and marginalization many hijras live in groups, under the leadership of an elder member called guru, a mother-like figure. Violence, lack of education (school dropouts are very common among trans people) and access to formal employment are stringent issues, both in rural and urban contexts. Away from courts and royal palaces where they used to have a “role”, in modern times this traditional cultural identity, faced with the endemic discriminatory structure of the Indian society and its hierarchical social division, was left with little space to survive. Besides some exceptions, begging and prostitution are the few available livelihoods for hijras. This is the case of Nisha, born in a poor family who “noticed her being different” as she was a toddler. A guru has taken care of her since she was a kid. She has never attended school nor is she familiar with the solidarity networks outside the hierarchy of her chosen family. “The amount of pain and suffering we go through is so much. We have nothing to look forward to. People harass us on the streets and everywhere we go, they even beat us. I have no will to live for long,” she says in a whisper.

“We are under gurus who check on our behavior so as not to put the community in a bad light. It’s a family, someone who is responsible for you,” tells me Rudrani, 40, a brilliant exception of a trans woman activist, model and actor, who is the founder and director of Mitr Trust, an organization that works on HIV/AIDS prevention. “It’s a system, if your family disowns you where do you go? Gurus are shelters, anchors, they protect us, groom us and teach us survival. They are teachers, parents and mentors.” Activists have opposed the Bill for forcibly trying to rehabilitate trans people with their biological families or shelter homes, for criminalizing the community for begging but it’s being silent on the issue of reservation in jobs and education, while watering down criminal provisions and laws for hate crimes and assaults on trans persons. The punishment for sexual violence against a transgender person is in fact substantially lower than that for rape and sexual assault against women (a maximum of 2 years compared to 7 for women). “The Bill doesn’t give any provision about the rampant issue of sexual violence. Rape and assaults of trans people are happening with an alarming frequency in India, but we don’t get enough media attention,” denounces Zainab. Despite the numerous recommendations deposed by trans groups, experts and legal advocacy groups to the Parliamentary Standing Committee, the Bill is regressive and presents a series of criticalities yet it contains a better description of transgender person than the one contained in the previous draft, which opened with a disturbing definition: “neither wholly female nor wholly male; or a combination of female or male; or neither female nor male.” A description that seems to describe intersex individuals rather than trans, and probably derives from the mythical figure of the Hindu god Ardhanarishvara, a form of the god Shiva composed of a half-male and half-female body. “The new Bill has finally adopted the definition of transgender persons as per the NALSA judgement. Yet, the problem is not the definition, but the provisions,” points out Zainab, “hijras in India are cut out of mainstream education and jobs, yet when it comes to addressing economic inequalities the government has no road map”. State and central governments have in fact disregarded the recommendations of the Supreme Court to extend reservation in education and employment to the transgender community. “This Bill makes a mockery of my personhood and will only add to everyday humiliation and violations”, she adds.

“I learned about intersexuality at the age of 22. But even before that I knew that I was different, that my body was different,” explains Chinju, 25, a Dalit and trans rights activist from Kerala. It’s when he attended a gender and sexuality workshop organized by a Dalit feminist group that he learned that “hermaphrodite” is the name doctors use when a person is born with a combination of male and female biological traits – the term is no longer in use, the correct one is intersex. He learned that the word is an umbrella term, like trans, which includes many variations. He cried after this eye-opening workshop. “I’m the only intersex person in Kerala to be out, but in India we are many,” he says. According to experts, around 1.7 per cent of the world population is born with intersex traits, yet people with these variations face stigmatization and discrimination, including infanticide, abandonment, abuse and corrective surgeries at early age. “My parents brought me up as a girl. They showed me to many doctors. At that time, they all suggested a corrective surgery. Only one doctor advised them to postpone it until I would be old enough to decide. I was lucky, my parents listened to him and when I turned 16 we consulted a surgeon, but I wanted to continue my studies. I knew I would have had problems if I had changed gender on my IDs” he says. “People asked many intrusive and inappropriate questions about my sexuality, my body. Often, I have no answers because I do not fit into their narrow binary mindset. When people bullied me, I started fighting back, I became very bold and handled many situations. At 22 I joined the queer movement.” Chinju, who has participated in Lok Sabha election 2019 from Kerala, has ever since been a very vocal LGBT and Dalit’s rights activist and has engaged in grassroots work advocating for an intersectional understanding of marginalities.

Discrimination is often the result of multiple and overlapping levels of oppression based on caste, sex, religion, language, and geography. According to feminist and Dalit scholars who acknowledge that gender identity and sexual orientation are not the only forms of selfhood and that people have multiple identities – it is important to look at gender issues and related violence in India (but not only) through the lens of intersectionality. Discrimination is often the result of multiple and overlapping levels of oppression based on caste, sex, religion, language, and geography. Aijaz is a social worker and LGBT ally and activist from Kashmir, where Indian forces de facto occupation in the region that resulted in widespread tortures, abuses, forced disappearing and extrajudicial killings. The 30-year-long occupation, who had, and still has, a great impact on civilians, was coronated last August when the Indian government stripped Kashmir of its autonomous status. The annexation of Kashmir and the military siege imposed in the region was accompanied by the longest internet shut down in history (140 days) whereas its main city, Srinagar, is considered the internet shut down capital of the world. “In Kashmir we have to maintain a very low profile because of the conflict, because of religious extremism,” argues Aijaz, “We have many layers of oppression here: the community, the Muslim identity and then the conflict, the caste system, the gender.” All these structural identities play a big role in the construction of a person: intersectionality studies show how interlocking systems of power and oppression affect the marginalized groups.

I realized I am not alone and there are so many more people like me, living freely. It was like a revelation. I felt the whole world into myself. R. is a 28-year-old lesbian-identifying Kashmiri girl who asked for her portrait not to show her face and name. “My family doesn’t know about me, very few people know who I am, what I do. I was never attracted to boys; I was never fitting to the image of a usual girl. Finally, in my college days I was exposed to more information and I came to know about the word ‘lesbian’. Reading a novel, I found this term, but I couldn’t find any reference to it in Kashmiri language. On the internet I finally read about people like myself, I had a definition for who I was. I realized I am not alone and there are so many more people like me, living freely. It was like a revelation. I felt the whole world into myself. I once talked to my siblings and their view was totally patriarchal and dogmatic, religion-biased and old-minded. ‘This is sin, you talk rubbish,’ they told me. Even my smaller brother judges me. My family makes me feel guilty, just the word lesbian makes them shiver,” she says staring the floor. “They would prefer to kill me [rather than accept my sexuality]. Here honor killings are not denounced, they don’t get called with their name. Some murders are portrayed as suicide. I fear for my life and I am dying a slow death”. Family support, or at least a non-hostile environment, can be big game-changers in the life of a queer person: acceptance is often a key factor in the well-being, resilience and self-esteem of young adults, who are forced to fight enormous battles to explore, and then affirm, their sexual or gender identity.

“In India we cannot understand queerness if we do not understand caste,” asserts Dhrubo Jyoti, 29, a Dalit and genderqueer journalist writing about gender, caste and sexuality. “Many members of what we call LGBT community are not just queer, but are also low caste, or Muslim, or Adivasi. They are already a minority. Or think about women. We know that lesbians and trans women face far more resistance and discrimination than gay men do. Also, in cities like Delhi women face alienation and discrimination even in queer spaces. So, we cannot understand LGBT issues if we don’t understand first the kind of oppression that comes from caste, gender and religion. We cannot think about a single, unified LGBT movement.” Indeed, many people reproach the movement for still not being fully inclusive and being divided into factions that cut across different lines based on class, caste, religion, rural/urban divide, education and gender. “In India the movement is multi-layered. Of course, it’s gay men who dominate the LGBT community: lesbian women, for example, they have this pressure, because we live in a patriarchal society, it’s difficult to be a woman in India. Many lesbians are not out because it’s more difficult for them. It’s definitely harder for women, as gay men we still have some privileges,” claims Sukhdeep, a gay-identifying IT professional, founder and editor of Gaylaxy, an online magazine on LGBT issues. When he first started publishing the magazine in 2010, he got an incredible response. “So many people in hetero relations, wrote about their personal stories and need to come out. The posts have been a source of hope for many people who feel alone in rural India, in oppressive families or in less open places than metro cities. Social media is the prime resource for queer people. For a very long time I was only connected to the community in virtual life. Forums help people feel more comfortable and give inspiration to come out,” he says.

]That the movement is divided and somehow crossed by different lines is in a way no surprise given the country’s variegated social fabric and profound divisions. Yet, it has achieved a lot in these twenty years thanks to the boldness of many people and it has succeeded in creating (virtually and physically) a space for queer individuals to come together and claim their role in society amidst the challenges, abuses and prejudices they face daily. “Yet now it’s not only about pride marches in India but the movement has further expanded creating other events like queer film festivals in Mumbai, Bangalore , Chennai and, from last year, also Queer literature festival. It started in Chennai, then Lucknow and this year Delhi also had one. “There were not only LGBT individuals attending the Rainbow Lit Festivalin Delhi but also many non-queer people from the civil society. It’s a very radical change and a very recent phenomenon,” asserts Sukhdeep.

That the society at large is opening up and becoming more inclusive is particularly true in big cities where diverse interactions as well as the urban anonymity leave far greater space for self-determination and identity building, of which sexual orientation and gender identity are fundamental parts. A generation of bold queer individuals who have pushed the walls around them breaking the gospel of patriarchal families and traditional structures. Despite all these breakthroughs, the way is still long to the full acceptance by the larger society and the recognition of the community’ rights, not least because of regressive laws such as the Trans Bill. Or the National Register of Citizens piloted in Assam: an exclusionary exercise to weed out “undocumented migrants” of Bangladeshi origin, planned to be extended to the rest of India. The mass census in Assam has turned out excluding almost 2 million people and, among them, many individuals from the trans community whose documentation is hardly consistent in terms of name and, hence, descent. When Section 377 was read down lifting the ban on homosexuality in India, Justice Indu Malhotra used these words: “History owes an apology to the members of this community and their families for the ignominy and ostracism that they have suffered through the centuries. The members of this community were compelled to live a life full of fear of reprisal and persecution”. An apology that is yet to fully come.

SUPPORT US

We like bringing the stories that don’t get told to you. For that, we need your support. However small, we would appreciate it.