What does it mean to live under the constant fear of being declared a foreigner in your own country? Personal notes on citizenship and belonging

In this personal narrative, Ambarien Alqadar reflects on her experience as an Indian Muslim in light of the establishment of the National Register of Citizens and the Citizenship Amendment Act.

Few months ago, I got a call from my brother in New Delhi, India. He wanted to know if I had documents from our father’s briefcase that proved he was in India before the midnight of 24 March 1971, a day before East Pakistan declared war on West Pakistan. That war concluded with East Pakistan formally changing its name to Bangladesh. It is believed that many people crossed into the bordering Indian state of Assam during this time. In 2013 the Indian State began scrutinizing the citizenship status of the 33 million residents in Assam, which it believed had been illegally infiltrated by Muslims. The goal of the National Register of Citizens (NRC) was to identify Indians and separate them from the migrant Muslims. At the end of August 2019, the final list was published, with 1.9 million people unable to prove their citizenship. And while the exercise drew strong reactions from the international human rights communityover the fate of millions of stateless citizens under The Citizenship Amendment Act 2019, the Indian government announced its plans to conduct it at a national level.

My father passed away in 2013 and I moved to the United States in 2015 to pursue a full-time teaching position. Every summer since then I have gone back to India – the land of my ancestors, my ‘motherland.’ United States of America in my imagination is my ‘homeland.’ On one such visit earlier last summer I opened my father’s briefcase that had remained closed for a long time. Dust and mold had set into deep corners, but the tan colored Samsonite briefcase in hard-shell from the 1970s had clearly stood the test of time. My father bought it as a gift for himself when he landed his first teaching job at the University of Tripoli, Libya. My mother tells me he was so proud of it that he would pose with it in pictures. This explains the mystery of the tan colored hard-shell briefcase making an appearance in our family album.

The briefcase smelled musty, full of duty-free airport perfumes from the time he had travelled. I found tickets, boarding passes, passports, photocopies, work permits and IDs. Tucked in between those was a stack of letters. Written over a period of three years, they were addressed to my mother while she was in India giving birth to me and my brother. There were letters giving detailed instructions on how to board airplanes and take connecting flights with infants. Then, there were those telling her to pack light but carry his favorite things. If there was a way India could be touched and felt on the Mediterranean Sea shore, it was through the sight and smells of pickle jars, sweets and jam bottles. While living in subsidized university housing with shared kitchen and bath, my father felt he had built a good life. In one of the letters, he wrote about how the university had offered to pay a family return ticket to India once a year. Though the job itself was not ideal, this one benefit made the offer irresistible.

My father was born in Sultanpur, a Muslim village of approximately 50 families in Azamgarh district in the Indian state of Uttar Pradesh sometime before 1947. The nearest public high school was about 5 miles from the village. Along with his older brother, my father became a local legend for walking barefoot to school on hot summer afternoons. This made him a first-generation learner not only in my family, but in the entire village. After a bachelors’ degree in Mechanical Engineering from the Aligarh Muslim University, my father did his Masters from the Indian Institute of Technology, New Delhi. This actually made his marriage offer to my maternal grandfather very attractive. There was a rare consensus in my family that my father displayed the traits of what we called a ‘good Indian Muslim.’

I grew up unravelling the meaning of the term through passionate, post-dinner, living room conversations. It meant an unflinching belief in India as a pluralistic nation.I grew up unravelling the meaning of the term through passionate, post-dinner, living room conversations. It meant an unflinching belief in India as a pluralistic nation. My father proudly cheered for the Indian cricket team when it played Pakistan and taught me and my brother how to sing patriotic songs. He took pride that his family was one of the thirty-five million Muslims who stayed back in India after the Partition even though some sixty million of her ninety-five million Muslims (one in four Indians) became Pakistanis in 1947. This made us the largest Muslim minority in a non-Muslim state. And even though both my parents lost family members to the other side – cousins, uncles, aunts whom they never saw again – they never weighed that pain against what India meant to them.

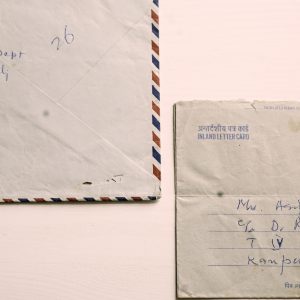

I was about three years old when my father’s teaching contract at the University of Tripoli ended. My mother was back in India waiting for my younger brother to arrive while he was sharing an apartment with Mr. Singh, a close family friend. Upset, Singh Uncle, as I called him, made a long-distance phone call to my mother telling her how my father had made a secret plan to move back to India. Singh Uncle believed Muslims in India will always remain what he called “second class citizens.” My mother recalls how the stress of that call sent her into premature labor. To keep Singh Uncle happy, my father applied for teaching positions in Canada. Looking through the briefcase, I found moth eaten job offer letters; too fragile to be held or read. I also found a frayed admission letter to the graduate school at the Tuskegee University, Alabama. My mother’s voice quivered when she held a light blue, stamped aerogramme in her hand. She recalled how my father wrote how much he missed India. And that he had saved enough money to build a home and wanted to raise his family in the place he belonged. His final words on this last letter before my family moved to India were that it was better being a minority in one’s motherland rather than becoming a mohajir[immigrant] in an adopted homeland.

My childhood memories in New Delhi are full of waking up to the sound of distant temple bells layered with the muezzin’s early morning call to prayer. Eid brought me the same happiness as did Durga Puja and Diwali. For all the love for non-vegetarian recipes passed on through generations in my family, beef was never served on our dinner table. We were taught to respect the Hindu belief of the cow as a sacred animal so much so that even now when I walk by The Five Guys serving hamburgers my spine shivers. Fearing the tag of the ‘meat eating Muslims,’ my mother spent afternoons experimenting with delicious vegetarian replacements. At bed time she told us stories from the life of Lord Krishna, whom she believed was the heavenly messenger sent to the East, much like Moses, Jesus and Prophet Muhammed, to enlighten the world. I came of age wearing two skirts to school – an ankle length covered a shorter one which sat six inches above my knees. The tent like, long skirt allowed me the anonymity of the good Muslim girl as I traversed my dense neighborhood full of onlookers on my way to school. Once on the school bus and beyond what my friends called the ‘border,’ I would take it off; actively reinventing myself as an assimilated Indian Muslim.

What did we do to deserve this? What does it mean to live under the constant fear of being declared a foreigner in your own country?Later in life with an onslaught of Parkinson’s and dementia, my father recalled the trains. He spoke of them ominously cutting through rural landscapes and sometimes arriving at stations full of the mutilated and disfigured bodies of uprooted refugees, who were crossing over to the other side of the border during the Partition of 1947. I wonder why he buried this image so deep and why it erupted as a repressed memory. He passed away few months before the Bharatiya Janata Party, led by its agenda to redefine India as a Hindu nation, came to power. Though I miss my father deeply, I’m happy he is not here to see the rising tide of hatred against Muslims, who are forced to face a hyper-nationalist narrative that criminalizes them, subjects them to excessive law enforcement and projects them as outsiders. The NRC unlocked a national conversation on the spectrum of legality and illegality of being Indian. The Indian Citizenship (Amendment) Act 2019 promises citizenship to migrants from all other communities except Muslims. What did we do to deserve this? What does it mean to live under the constant fear of being declared a foreigner in your own country? Where does this dispossession from the social and political life of your nation take you? What are the limits to this dispossession and what toll does it take on mental and emotional health? I don’t have answers to these questions.

Looking at the barren trees through my study window, I’m haunted by the specter of detention centers being built in far-flung corners of India. On my Facebook feed, viral videos of Muslim men being openly lynched make my stomach turn. I don’t have a language to articulate that fear except that I can hear its heavy steps draw near. On many days I find it hard to make sense of the ‘here’ and ‘there’ of my existence. As I held scraps of the letters in my hands, I asked myself what could they prove, if anything at all? And in that moment, the personal archive of my father became a proof of his belief in an inclusive idea of India. I thought of the millions of other Muslim families frantically searching through family documents – birth records, ancestry and residency documents to prove they are Indians. I can only imagine what this moment means to them. What about the poor who lost those documents in floods, fires or earthquakes? What will they have to sell from the little that remains to get duplicate copies done? I folded the letters neatly and packed them in my carry-on luggage alongwith his reading glasses that still smell of him.

I had just finished teaching for the day. A colleague walked into my office and asked me how I was doing. I had hugged her and cried a few weeks ago. I told her that things were not so bad and that I was getting paranoid. Coming to terms with my own status as an ‘alien,’ I wondered if my paranoia was an end in itself. Fearing surveillance, I watched my words when I talked to my family over the next few days. To my brother’s question on the phone, I told him I had the letters and how often I read them. We joked and then there was a long silence. I told myself this was not just my story, or the story of my family, but this is the story of 14 percent of India’s people.

I was just beginning to take this as my new normal when my city, New Delhi, erupted into a gruesome episode of anti-Muslim violence and I received another call from my brother.