Walking the talk on women’s freedom and social equality: A profile of Devangana Kalita

“At no time have governments been moralists. They never imprisoned people and executed them for having done something. They imprisoned and executed them to keep them from doing something. They imprisoned all those prisoners of war, of course, not for treason to the motherland […] They imprisoned all of them to keep them from telling their fellow villagers about Europe. What the eye doesn’t see, the heart doesn’t grieve for.”― Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, The Gulag Archipelago, 1918-1956

A political prisoner is a person who is imprisoned for their belief. Regimes across the globe arrest people for who they are and not for what they have done, thus making the category of the political prisoner into a criminal offense. It is a thought crime: the crime of thinking, acting, speaking, probing, reporting, questioning, demanding rights and, more importantly, exercizing citizenship. It is also a crime of existing in a Black, Brown, Muslim body that can be targeted and punished for who they are, or what they represent.

These inhumane incarcerations do not just target private acts of courage, they are bound together with the fundamental questions of citizenship, and with people’s capacity to hold the State accountable – especially States that are unilaterally and fundamentally remaking their relationship with their people.

The assault on the fundamental rights has been consistent and ongoing at a global level and rights-bearing citizens are transformed into subjects of a surveillance State.

In this transforming landscape, dissent is sedition, and resistance is treason.

A fearful, weak State silences the voice of dissent. Once it has established repression as a response to critique, it has only one way to go: to become a regime of authoritarian terror, a source of dread and fear for its citizens.

How do we live, survive, and respond to this moment?

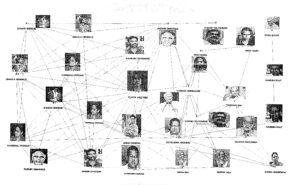

With Profiles of Dissent, The Polis Project works with individuals and organizations across the world to question and critique the State that has used legal means to crush dissent illegally and eliminate questioning voices.

It also intends to ground the idea that, despite the repression, voices of resistance continue to emerge every day.

DEVANGANA KALITA

Devangana Kalita is a 31-year-old feminist activist and research scholar. She is a founding member of the women students’ collective Pinjra Tod and has been involved in women’s and students’ movements for over thirteen years. She studied English Literature at Delhi University, completed a Masters in Women and Development at the Institute of Development Studies (IDS), University of Sussex, UK and a Masters in History at Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU) in Delhi. She is presently writing her MPhil dissertation at the Centre for Women Studies (JNU) on women’s histories of labor and resistance, focusing on women tea plantation workers in Assam. Her research work, like her activism, looks at women’s political participation and the intersection of patriarchy with other structures of economic, social and cultural oppression.

Devangana Kalita grew up in Dibrugarh, Assam. Her childhood was deeply influenced by the secular outlook of her father, who introduced her to a world of progressive literature and ideas questioning social disparities. Yet such ideas were soon confronted with the reality of discriminatory cultural practices, humiliation and loss of agency faced by women and with the struggles of her mother and other women around her, who despite their education and profession, continued to have to battle for their independence, equality and dignity. The contradiction between the promise of women’s freedom and dignity and its constant undermining through family, community and state institutions remains a central political concern for Kalita, who turned her education into a means to connect more deeply with society, constantly looking for opportunities to understand and work on various social and political questions.

Her postgraduate studies in the UK helped Devangana Kalita expand her political horizon: engagement with issues of race, geopolitical conflicts, dispossession and ecology came not as an academic exercise but through deep friendships and exchanges with people from diverse backgrounds and different parts of the world.

When she returned to India, Kalita continued her engagement with women tea plantation workers in Assam as well as her solidarity work, particularly with the ongoing movement in Niyamgiri. By 2014, the formation of the Modi government rapidly transformed the political terrain in India, defining a new ground for women’s rights, security and freedoms under an increasingly misogynist rightwing regime.

Since 2015, Pinjra Tod has been Kalita’s primary focus. The collective emerged out of a recognition that young women in universities in Delhi face discrimination, sexual harassment, inadequate resources, paternalism, moral policing and have little space to raise these issues collectively. Pinjra Tod was also an inclusive space of friendship and mutual support for women discovering their independence from their families and patriarchal institutions. The movement brought many young women to the forefront of student activism on campus, becoming a strong voice of opposition to the Akhil Bharatiya Vidyarthi Parishad (ABVP) in Delhi University and confronting their sexism and hooliganism on various occasions. At the same time, the collective sought to connect everyday discrimination faced by young women with larger structures of caste and neo-liberal exploitation.

When the central government passed the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) in December 2019, Kalita was among the thousands of students who took to the streets against the draconian act, challenging it as discriminatory, divisive and unconstitutional. As a witness to the unflinching resolve of the Muslim women who were leading the protests in the capital and across the country, Kalita stood as an ally. It was the strength of this togetherness that brought the wrath of the Police and the State administration upon Devangana Kalita, along with other women protestors.

On 19 April 2020, the Delhi Police visited Kalita’s residence and seized her and her flat mate Natasha Narwal’s phones. The following month, they received a notice for interrogation under the Unlawful Activities Prevention Act (UAPA) and were questioned for over two hours by the Delhi Police Crime Branch. Minutes after the interrogation ended, another team from the Jafrabad Police station arrived at their house and took them under arrest.

Date of arrest: 24 May 2020

Charges: Booked with more than fifty charges, Devangana Kalita has been arrested under four First Information Reports (FIRs). She was first booked on 23 May 2020, in FIR 48/2020 by the Jaffrabad Police Station where she has been charged for participating in a road block under the Jaffrabad metro station on 22 February 2020. The FIR contains charges of obstructing and disobeying a public servant, hate speech, use of assault or criminal force to deter public servant in the course of duty, danger or obstruction of public way and rioting. Subsequently, on 24 May 2020, she was booked by the Jaffrabad Police in FIR 50/2020, which also pertains to the Jaffrabad roadblock and contains accusations of rioting with deadly weapons, voluntarily causing hurt, attempt to murder, murder and criminal conspiracy among other charges. The third FIR (250/2019) has been filed by the Daryaganj Police Station on 30 May 2020 in relation to a protest march in the area and contains charges of voluntarily causing grievous hurt and assault to deter public servant from discharging the duty. The fourth FIR (59/2020) frames the Delhi riots as a premeditated conspiracy and identifies Kalita among the conspirators of the riots along with other students and activists. This FIR was filed by the Crime Branch and is being investigated by the Special Cell. It books Kalita under sections of the UAPA including terrorism and includes penal charges of rioting, attempt to murder, murder and criminal conspiracy.

Location of work: Delhi

Update: Devangana Kalita is currently lodged in Tihar Jail; her bail hearing for the UAPA case is presently ongoing in the Delhi High Court. She has been granted bail in three of the four cases against her. Kalita has filed a writ petition for prison reform while in jail, asking for – among other things – increasing inmates access to virtual and physical meetings with longer duration, reducing the time required for visitors to complete meeting formalities, provisions to increase women prisoners’ ability to connect with their families, guaranteeing inmates’ access to relevant legal materials, communications and updates on their cases. She remains in jail where she keeps busy working on her MPhil dissertation, helping out with legal support and teaching and playing with the many small children who live with their mothers inside the jail. Along with her fellow inmates Natasha Narwal and Gulfisha Fatima, she helped organize an event for International Women’s Day, engaging her fellow inmates in singing, dancing and theatre performances, all focused on understanding and spreading awareness of women’s issues and struggles.

Her arrest has been condemned by various platforms and organizations in India and internationally, including the World Alliance of Citizen Participation, Frontline Defenders and the Director of the Institute of Development Studies – Kalita’s alma mater.

Excerpts from Devangana Kalita’s letters from jail to PT

The unknown awaits us, we will have to embrace it with all the courage we can muster together, open ourselves to new beginnings and the harshest of challenges, a new reality that has arrived too soon, too suddenly, it’s incredibly daunting and scary, but I believe we are together slowly learning to navigate and inhabit it. What can we do but move forward, learning from the history of the world and our own, to equip ourselves to handle what is unfolding and awaits; it is also a graver responsibility.

Just like a factory, a plantation, a hostel – it is yet another place that imprisons the working classes and imprisons women. Sometimes I feel like I am in a play, I am acting in it but also observing it, keenly and deeply. We practice almost the same scenes everyday, but yet there is difference, a new scene, a new story, a new role — there is life and struggle in its barest desperate forms constantly playing out, there is never stasis, at least not until now.

What is a woman’s life under patriarchy but a training for being in jail? What is a woman’s life under patriarchy but a training for being in jail? When a jail staff instructs you not to go here or there, it’s not extraordinary, women are always told by fathers, husbands, lovers to not go here or there. At least in jail, the exercise of power is clear and transparent, unlike in the case of family or society where there is all the paraphernalia of ‘love’, ‘honour’ etc. When the matrons come to lock our barracks at 6:30 pm and mark attendance, it does not feel alien, it feels exactly like being back in the hostel, a weird deja vu. The Jail Manual reads like a hostel rule book. Actually, it entitles you to better legal protection than hostel rules do!

It of course wasn’t easy initially given that in the ‘outside’ world, it is these exact structures and norms that one so relentlessly fought against, the irony of all the layers and layers of locks and chains and bars and CCTVs constantly staring at you, reminding you of this cruel joke each passing moment, was very difficult to take. There was also the shock of the initial rupture, it did take some time to absorb and ‘settle in’, to build spaces of autonomy, independence and collectivity, to understand how to tackle the task and responsibility of surviving incarceration.

It is women’s defiance and collectivity that helped one survive ‘outside’, it is the same that is crucial to surviving ‘inside’, in jail. There are so many life stories, a new world, a different world, pushing you constantly to think, there is so much to absorb, so much pain, so much despair, yet moments of joy, of singing, of surviving. Every day I draw strength from the women who have been here for many years, women who have no-one ‘outside’, who are endlessly waiting through long trials, women who are from far away countries and don’t even speak English or Hindi, women who have delivered their babies here and bring them up here, women who do not have money to hire lawyers and patiently negotiate the arduous process of the government legal aid system, women who have not spoken to anyone in their families for months because they just cannot remember or find a contact number and no one respond to their letters ‘home’, women who are as much ‘criminals’ as prisoners of structural oppressions. I cannot write about fellow inmates in letters, but I do have a name for the prison memoir, “Hum Gunehgar Auratein”.

Meanwhile another very reassuring thing has been to still have skies as our companion, we have a cute little park with birds, squirrels and butterflies, where we sat and observed many monsoon clouds pass by, on a magical evening, which incidentally happened to be the day of my High Court hearing in the 50/20 FIR, we even witnessed a clear full arc rainbow. The skies are visible from our barrack windows too where the full moon has diligently risen every month. So yeah, they could not snatch our blue skies, our bougainvilleas, our dreams, our songs, they never will be able to.

Related Posts

Walking the talk on women’s freedom and social equality: A profile of Devangana Kalita

DEVANGANA KALITA

Devangana Kalita is a 31-year-old feminist activist and research scholar. She is a founding member of the women students’ collective Pinjra Tod and has been involved in women’s and students’ movements for over thirteen years. She studied English Literature at Delhi University, completed a Masters in Women and Development at the Institute of Development Studies (IDS), University of Sussex, UK and a Masters in History at Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU) in Delhi. She is presently writing her MPhil dissertation at the Centre for Women Studies (JNU) on women’s histories of labor and resistance, focusing on women tea plantation workers in Assam. Her research work, like her activism, looks at women’s political participation and the intersection of patriarchy with other structures of economic, social and cultural oppression.

Devangana Kalita grew up in Dibrugarh, Assam. Her childhood was deeply influenced by the secular outlook of her father, who introduced her to a world of progressive literature and ideas questioning social disparities. Yet such ideas were soon confronted with the reality of discriminatory cultural practices, humiliation and loss of agency faced by women and with the struggles of her mother and other women around her, who despite their education and profession, continued to have to battle for their independence, equality and dignity. The contradiction between the promise of women’s freedom and dignity and its constant undermining through family, community and state institutions remains a central political concern for Kalita, who turned her education into a means to connect more deeply with society, constantly looking for opportunities to understand and work on various social and political questions.

Her postgraduate studies in the UK helped Devangana Kalita expand her political horizon: engagement with issues of race, geopolitical conflicts, dispossession and ecology came not as an academic exercise but through deep friendships and exchanges with people from diverse backgrounds and different parts of the world.

When she returned to India, Kalita continued her engagement with women tea plantation workers in Assam as well as her solidarity work, particularly with the ongoing movement in Niyamgiri. By 2014, the formation of the Modi government rapidly transformed the political terrain in India, defining a new ground for women’s rights, security and freedoms under an increasingly misogynist rightwing regime.

Since 2015, Pinjra Tod has been Kalita’s primary focus. The collective emerged out of a recognition that young women in universities in Delhi face discrimination, sexual harassment, inadequate resources, paternalism, moral policing and have little space to raise these issues collectively. Pinjra Tod was also an inclusive space of friendship and mutual support for women discovering their independence from their families and patriarchal institutions. The movement brought many young women to the forefront of student activism on campus, becoming a strong voice of opposition to the Akhil Bharatiya Vidyarthi Parishad (ABVP) in Delhi University and confronting their sexism and hooliganism on various occasions. At the same time, the collective sought to connect everyday discrimination faced by young women with larger structures of caste and neo-liberal exploitation.

When the central government passed the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) in December 2019, Kalita was among the thousands of students who took to the streets against the draconian act, challenging it as discriminatory, divisive and unconstitutional. As a witness to the unflinching resolve of the Muslim women who were leading the protests in the capital and across the country, Kalita stood as an ally. It was the strength of this togetherness that brought the wrath of the Police and the State administration upon Devangana Kalita, along with other women protestors.

On 19 April 2020, the Delhi Police visited Kalita’s residence and seized her and her flat mate Natasha Narwal’s phones. The following month, they received a notice for interrogation under the Unlawful Activities Prevention Act (UAPA) and were questioned for over two hours by the Delhi Police Crime Branch. Minutes after the interrogation ended, another team from the Jafrabad Police station arrived at their house and took them under arrest.

Date of arrest: 24 May 2020

Charges: Booked with more than fifty charges, Devangana Kalita has been arrested under four First Information Reports (FIRs). She was first booked on 23 May 2020, in FIR 48/2020 by the Jaffrabad Police Station where she has been charged for participating in a road block under the Jaffrabad metro station on 22 February 2020. The FIR contains charges of obstructing and disobeying a public servant, hate speech, use of assault or criminal force to deter public servant in the course of duty, danger or obstruction of public way and rioting. Subsequently, on 24 May 2020, she was booked by the Jaffrabad Police in FIR 50/2020, which also pertains to the Jaffrabad roadblock and contains accusations of rioting with deadly weapons, voluntarily causing hurt, attempt to murder, murder and criminal conspiracy among other charges. The third FIR (250/2019) has been filed by the Daryaganj Police Station on 30 May 2020 in relation to a protest march in the area and contains charges of voluntarily causing grievous hurt and assault to deter public servant from discharging the duty. The fourth FIR (59/2020) frames the Delhi riots as a premeditated conspiracy and identifies Kalita among the conspirators of the riots along with other students and activists. This FIR was filed by the Crime Branch and is being investigated by the Special Cell. It books Kalita under sections of the UAPA including terrorism and includes penal charges of rioting, attempt to murder, murder and criminal conspiracy.

Location of work: Delhi

Update: Devangana Kalita is currently lodged in Tihar Jail; her bail hearing for the UAPA case is presently ongoing in the Delhi High Court. She has been granted bail in three of the four cases against her. Kalita has filed a writ petition for prison reform while in jail, asking for – among other things – increasing inmates access to virtual and physical meetings with longer duration, reducing the time required for visitors to complete meeting formalities, provisions to increase women prisoners’ ability to connect with their families, guaranteeing inmates’ access to relevant legal materials, communications and updates on their cases. She remains in jail where she keeps busy working on her MPhil dissertation, helping out with legal support and teaching and playing with the many small children who live with their mothers inside the jail. Along with her fellow inmates Natasha Narwal and Gulfisha Fatima, she helped organize an event for International Women’s Day, engaging her fellow inmates in singing, dancing and theatre performances, all focused on understanding and spreading awareness of women’s issues and struggles.

Her arrest has been condemned by various platforms and organizations in India and internationally, including the World Alliance of Citizen Participation, Frontline Defenders and the Director of the Institute of Development Studies – Kalita’s alma mater.

Excerpts from Devangana Kalita’s letters from jail to PT

The unknown awaits us, we will have to embrace it with all the courage we can muster together, open ourselves to new beginnings and the harshest of challenges, a new reality that has arrived too soon, too suddenly, it’s incredibly daunting and scary, but I believe we are together slowly learning to navigate and inhabit it. What can we do but move forward, learning from the history of the world and our own, to equip ourselves to handle what is unfolding and awaits; it is also a graver responsibility.

Just like a factory, a plantation, a hostel – it is yet another place that imprisons the working classes and imprisons women. Sometimes I feel like I am in a play, I am acting in it but also observing it, keenly and deeply. We practice almost the same scenes everyday, but yet there is difference, a new scene, a new story, a new role — there is life and struggle in its barest desperate forms constantly playing out, there is never stasis, at least not until now.

What is a woman’s life under patriarchy but a training for being in jail? What is a woman’s life under patriarchy but a training for being in jail? When a jail staff instructs you not to go here or there, it’s not extraordinary, women are always told by fathers, husbands, lovers to not go here or there. At least in jail, the exercise of power is clear and transparent, unlike in the case of family or society where there is all the paraphernalia of ‘love’, ‘honour’ etc. When the matrons come to lock our barracks at 6:30 pm and mark attendance, it does not feel alien, it feels exactly like being back in the hostel, a weird deja vu. The Jail Manual reads like a hostel rule book. Actually, it entitles you to better legal protection than hostel rules do!

It of course wasn’t easy initially given that in the ‘outside’ world, it is these exact structures and norms that one so relentlessly fought against, the irony of all the layers and layers of locks and chains and bars and CCTVs constantly staring at you, reminding you of this cruel joke each passing moment, was very difficult to take. There was also the shock of the initial rupture, it did take some time to absorb and ‘settle in’, to build spaces of autonomy, independence and collectivity, to understand how to tackle the task and responsibility of surviving incarceration.

It is women’s defiance and collectivity that helped one survive ‘outside’, it is the same that is crucial to surviving ‘inside’, in jail. There are so many life stories, a new world, a different world, pushing you constantly to think, there is so much to absorb, so much pain, so much despair, yet moments of joy, of singing, of surviving. Every day I draw strength from the women who have been here for many years, women who have no-one ‘outside’, who are endlessly waiting through long trials, women who are from far away countries and don’t even speak English or Hindi, women who have delivered their babies here and bring them up here, women who do not have money to hire lawyers and patiently negotiate the arduous process of the government legal aid system, women who have not spoken to anyone in their families for months because they just cannot remember or find a contact number and no one respond to their letters ‘home’, women who are as much ‘criminals’ as prisoners of structural oppressions. I cannot write about fellow inmates in letters, but I do have a name for the prison memoir, “Hum Gunehgar Auratein”.

Meanwhile another very reassuring thing has been to still have skies as our companion, we have a cute little park with birds, squirrels and butterflies, where we sat and observed many monsoon clouds pass by, on a magical evening, which incidentally happened to be the day of my High Court hearing in the 50/20 FIR, we even witnessed a clear full arc rainbow. The skies are visible from our barrack windows too where the full moon has diligently risen every month. So yeah, they could not snatch our blue skies, our bougainvilleas, our dreams, our songs, they never will be able to.

SUPPORT US

We like bringing the stories that don’t get told to you. For that, we need your support. However small, we would appreciate it.