A New Economy: How Van Gujjars in Uttarakhand are trapped in a cycle of debt and dependence

Sharafat Ali Kasana lost his father, Noor Deen, in 2002. Deen, the head of the household at the time, led his family and other Van Gujjars to the alpine mountains in the summer for their annual migration from the Rajaji forest in Uttarakhand. He died during this migration, and Kasana still regrets that his father was not cremated until the day after his death, because they could not find a suitable burial ground, shroud, or anyone to lead the cremation prayers. “That was the last time we migrated to the mountains,” Kasana recalled. Over the decades, as restrictions on the free movement of Van Gujjars grew, the community was forced to adapt their migratory patterns for the benefit of their cattle, but the change has come at a grave cost—a cycle of perpetual debt.

The Van Gujjars are a Muslim, semi-nomadic, pastoralist community of Gujjars (also spelled Gurjars) spread across the forests of Himachal Pradesh, Uttarakhand, Uttar Pradesh, and Jammu and Kashmir. Their primary occupation is rearing a breed of mountain buffaloes commonly known as Gojri. As a transhumant community, the Van Gujjars migrate to the alpine forests of the upper Himalayas in the summer, and return to the hilly terrain of the Shivalik forest, which now falls within the Rajaji National Park, in the winters. The main purpose of the Van Gujjar migration, as I previously reported, is to find grasslands for their cattle while allowing the jungles in the lower Himalayas to rejuvenate, grow, and heal after a season of grazing and lopping—a traditional and sustainable method of tree shedding practised by Van Gujjars, also known as “rotational grazing.”

To sustain themselves, the Van Gujjars would sell milk products to towns and villages along their route, and buy their essentials in return, traditionally engaging in a barter practice, which evolved into a cash transaction, but nonetheless forming a self-sufficient economy. For several generations, the Van Gujjars were involved in this trade. Kasana’s grandparents would freely graze and use other resources of the forest for themselves and their cattle. “It all began to change when our movement within the forests was restricted,” said Shamshad, a local Van Gujjar community leader. “Now the Van Gujjars simply cannot depend on forest resources for feeding out cattle and we’ve to buy cattle feed from markets.” As a result, in recent decades, their traditional lifestyle has come under threat.

With the forests declared as national parks and tiger reserves, and the expansion of tourism projects associated to them, the Van Gujjars lost much of the access to their grazing lands. Even with grazing permits, they continue to face hostility from forest officials. Now, with fewer places to graze their cattle, they must rely on expensive market supplements and bulk purchases of cattle feed, which force them to take loans from local milk traders. These traders exploit the Van Gujjars by paying them a low price for their milk, transforming the self-sufficient, mutually beneficial economy into one of debt and dependence. In the process, the Van Gujjars have lost autonomy over their produce, and struggle to preserve their traditional way of life, adapting to the challenges and economic pressures of modern development.

Years before Deen’s death, Kasana and others had begun contemplating stopping their alpine migration because of the increasing hostility and restrictions. But his community still migrates from the Rajaji and Shivalik forests to Khaddar Ka Tapu—the floodplain of the river Ganga—in the Bijnore district of Uttar Pradesh for three months every year. The Gojri buffaloes cannot survive the extreme summers of the lower Himalayas, which for the past several years has been witnessing extreme rises in temperatures causing forest fires. “Even if our buffaloes could survive the harsh summer, it is economically impossible for us to stay in the jungle during summers,” Kasana said.

The transformation of the Van Gujjar economy

Meer Hamja, the founder of Van Gujjar Tribal Yuva Sangathan—a youth organisation of Van Gujjars working towards achieving forest rights for the community—believes the erosion of their rights began five decades ago. “The whole process of categorisation of forests into sanctuaries, parks, and reserves begun in 1974,” Hamja said. “Several conservation committees were formed and the forest department began to vigilantly curtail our movement within the forest we have freely lived in since generations. Slowly, with time, less and less grazing grounds were made available to us, and our sense of ownership to the jungle began to erode as we simply couldn’t rely on the forests for our survival.”

Hamja, like Kasana, comes from one among the several dozen Van Gujjar families who still live in the Rajaji forest, in the lower foothills of Himalayas, encompassing the cities of Haridwar and Rishikesh. In 1992, following its designation as a national park, the Uttarakhand forest department relocated 1,300 families from the Motichur and Ranipur areas of Rajaji forest to Patri and Gendi Khata villages of Haridwar, just near the borders of Bijnore district of Uttar Pradesh. A Mongabay report noted that another 1,300-1,600 people were relocated from the forests but without lands, forcing them to build temporary shelters near river banks across the valleys of Haridwar and Rishikesh. Gulam Rasool, a 44-year-old Van Gujjar I met at Kasana’s dera, told me that his brother was allotted land in Gendi Khata but he was not, forcing him to seek shelter at various places temporarily, often at the mercy of fellow Gujjars.

All the Van Gujjars I spoke with said they used to go to the alpine forests in Uttarkashi and Tehri Garhwal for their annual migration in the summers, until they were abruptly prevented from taking their usual routes from within the forest. Rasool last went to the alpine bugyals (grasslands) two decades ago in the early 2000s. “The journey itself was hard enough as it was, but the restrictions and other issues made it a lot more difficult,” he said. “It was not worth it even for our cattle.”

The Van Gujjars’ old migratory routes, such as those followed by Deen until his death, would often take a month to complete. The journey was marked by open spaces and forests that the transhumant pastoralists would traverse using set, predetermined routes and timetables, halting at the common lands of several villages along the way. The villagers relied on the Van Gujjars for milk products, like butter and ghee, in the absence of commercial markets in the higher altitudes.

“Those were different days,” Hamja said. “The villagers used to wait for us not only for our milk products but to sell their grass to us. They’d also buy jhotas”— male buffaloes—“from us for breeding purposed and used to barter their beef cow to us in exchange of ghee. Moreover, when we left, our herds used to leave them a substantial amount of dung, which they would use as manure.” Meer described the relation as one of mutual dependence with the villagers. “Earlier both of us were the same. Both were poor.”

All of this changed with the formation of the Uttarakhand state in 2000, and the plethora of development projects that came in the newly-formed state. A 2011 research study, titled “Adaptation and Coexistence of Van Gujjars in the Forests: A Success Story,” argues that despite forest restrictions and diversions, “the Van Gujjars have proved to be resilient and have an intact social structures and mechanisms for mutual sharing of resources for sedentary purposes.” The researchers, Rubina Nusrat, BK Pattanaik and Nehal A Farooqui, note that the Himalayan states have undergone drastic infrastructure developments in recent decades for the purposes of tourism, hotels, road construction, hydropower plants, and more. For defence purposes alone, the study found, a total of 16,653 kilometres of metalled and 2,593 kilometres of non-metalled roads were constructed in the region. “As a result, the Van Gujjars have had to alter their migratory routes and face problems of livestock being killed on roads, thefts and a constant pressure to move,” the researchers wrote. “There are instances where animals die due to eating noxious weeds growing close to the roads on degraded land.”

These developmental projects also improved the socio-economic conditions of the villagers with whom the Van Gujjars used to trade. The higher altitude areas in the state with better road connectivity saw a boom in the tourism industry creating more economic opportunities for the villagers. “The villagers left their old jobs and became sahabs (bosses) who were disgusted by even looking at cow dung,” Hamja said. Aman Chechi, the current president of Van Gujjar youth group, echoed the organisation’s founder. “After the development drive, the places where we previously had our traditional migration trails had pakka roads built over it now,” he said. “Our resting places had become hotels or dumping grounds for those hotels. Our presence there was not a good look for the villagers now.”

In addition, the increasing restrictions of movement within the forests due to the notification of national parks and sanctuaries further exacerbated the struggle of the Gujjars in their migration. In the years that followed, the Van Gujjars sought to continue their annual migration to the alpine meadows, adapting to new routes along roads. To avoid the heavy traffic that makes the mountainous terrain perilous, they travelled mostly at night, resting during the day. However, this shift brought its own challenges. While they once relied on grazing grass provided by villagers along the way, they were now forced to purchase expensive food supplements from the market to sustain their cattle.

The traditional barter system, where they exchanged milk products for essentials, had largely collapsed, leaving them struggling to find new markets for their dairy produce. The journey became even more arduous during the scorching summer heat, as they constantly had to search for water sources and suitable resting spots for their caravan of people and livestock. These adjustments added layers of complexity to an already difficult migration. This meant that, due to limited resources, they were forced to reduce the number of stops they could make along the way, pushing themselves to complete the journey with minimal supplies and greater strain.

Eventually, most Van Gujjars in the Shivalik region abandoned migrating to the alpines for a much nearer and much shorter migration to Bijnore for three months every year. However, back in the lower Himalayas, when the Gujjars return from the migration, they find hard to access the grasslands even with grazing permits and continue to be harassed by the forest rangers. Limiting their access to the forest with no grasslands has forced the Gujjars to buy feed for their cattle from the market.

An economy of debt, dependence and exploitation

Today, almost all Van Gujjars almost entirely rely on market products to feed their cattle. “There are no grasslands available for us,” Kasana said. “We cannot lop the trees anymore. How are we going to feed our cattle if we do not buy it from the market? The three months in Bijnore is the only time we don’t have to buy feed for our cattle.”

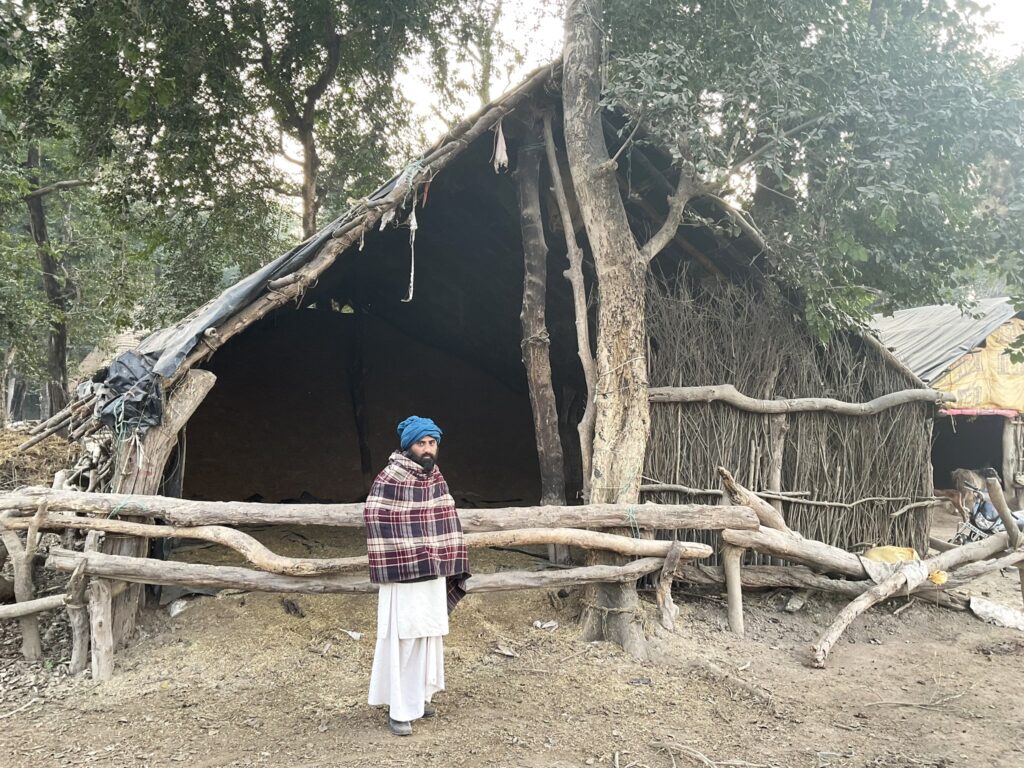

The Van Gujjars mostly buy four types of cattle feed for their buffaloes—mustard khal, chokar (wheat bran), pural and bhoosa (wheat straw). In Kasana’s dera—a small cluster of huts, built using mud and tree branches—each family has an additional hut to store these supplements. Sharafat needs khal and chokar worth Rs 8,50,000 every year, along with pural and bhoosa worth Rs 3,00,000, to feed his herd of 30 cattle, eight of whom give milk. “We don’t have the money to buy for our requirements in bulk. We have to seek help from the lalas.”

The lalas are how Van Gujjars refer to the milk traders who buy the milk from them. While the Van Gujjars could previously sell the milk to the different villagers along the way, it is now the lalas who have monopolised the market and control all purchases. In fact, the milk traders from the nearby city of Rishikesh and Haridwar have a peculiar business relation with the pastoralists—they not only buy the milk, but also provide loans to the Van Gujjars to buy the food supplements for their cattle.

Since the Van Gujjars are no longer travelling through numerous villages during their migration, they need to sell their milk and milk products at a wholesale scale, which is not possible for the villagers living near the Van Gujjars. It is this gap in the market that the milk traders have exploited, and instead of paying the herders, the lalas claim that the cost of the milk is offset against the price of the cattle feed they source and provide to the Van Gujjars. What appears to be a routine business practice has trapped the Van Gujjars in a cruel cycle of debt, dependence and exploitation.

Kasana’s calculation of Rs 11,50,000 annually for his cattle feed is a rough estimate. In reality, he has never made these purchases. Instead, his lala gets the feed delivered to his dera as and when it is necessary, so the actual purchase is made by the lala. In return, Sharafat and other Van Gujjars have to sell their milk to these traders at a relatively cheaper price.

But the Van Gujjars are never paid the amount for the milk they sell to their lalas upfront. Kasana sells 30 litres milk per day at Rs 50 per litre, but he has never been paid the daily earnings of Rs 1,500 that he is due, which roughly amounts to a monthly income of Rs 45,000 that is denied to him. Instead, Kasana and all other Van Gujjars I interviewed usually ask their lalas for money every once a while if they need anything, who gives them a meagre sum between Rs 500–1000, twice or thrice every week, in order to buy essentials. The rest of the money owed to the Van Gujjars as payment for the milk is treated as a part of repayment for the dues owed to the lala for the cattle feed.

I asked dozens of Van Gujjars whether they had any idea of how much money they owed to their lala, or how much their lala owed to them, or any specifics of the transactions between the two parties. None of them knew about the particularities of the business, even though they were doing transactions for years. “Most of the Van Gujjars are illiterate and they never kept records of the transactions,” Hamja said. He explained how the lalas treat the payment for the cattle feed as a huge, unquantified loan offered to the Van Gujjars. Consequently, every supply of milk is treated as a small repayment of this supposed loan, and Van Gujjars are effectively kept trapped in bonded labour, dependent on the lalas for their cattle feed, for the money for essential commodities, and forced to provide the milk at low rates and unable to sell it to anyone else.

“Now the situation is such that they are so afraid of their lalas that they fear asking for details,” Hamja added. While Kasana described his financial situation, another Van Gujjar added, “The loan never gets repaid. I know not a single person here who isn’t in debt from the lala.” Yet, as Hamja described, the Van Gujjar refused to be identified by name, out of fear that the lala would punish him for it. “It is a good business but only for the lala,” he continued. “He buys cattle feed for dozens of families here worth crores every year and avails huge discount on that but our loan is set on the market price. In return, he gets cheaper milk from us and we barely get enough to survive.” Kasana added, “The only benefit we receive from this milk trade is that we get the milk for our tea at home for free.”

The fear among the Van Gujjars of lalas was palpable in all conversations. All the Van Gujjars I spoke to refused to share the contact details of their respective milk traders out of fear that any reporting on them would have grave consequences for their daily livelihood.

One cold November afternoon in the Rajaji forest, when I was speaking to a group of Van Gujjars at a dera, our conversation was interrupted by the loud honk of a mini truck. It was the lala for the entire dera. The truck stopped at the farthest hut, two men quickly stepped out, and transferred the milk from a container kept outside one of the huts in the dera, into a container in the truck. The two then drove to the next hut, and then the next one, until the milk traders had taken the milk from all the Van Gujjar homes in the dera—around 20–30 in total. The entire collection was completed in less than an hour, without any exchange about the payment for the milk the lalas were collecting.

I sought to speak to the traders, but the Van Gujjars were vehemently opposed to the idea. I had to repeatedly assure them that I would ask simple questions that would not adversely affect them and their livelihood. Several of them followed me to the lala and surrounded the two of us to hear our conversation.

“The Van Gujjars tell me that you loan them tens of lakhs every year for their cattle feed, and take their milk at lower price as a form of repayment,” I said. “I did calculation of the loans you give and the milk you get in return from this dera. Why are you in a loss-making business?”

“I am only helping the Van Gujjars,” the milk trader answered. The trader, who runs a large dairy shop in Rishikesh city and buys around 700 litres of milk every day from the Van Gujjars, added that he too, like the Van Gujjars, was earning little and struggling to survive. The claim is difficult to believe, considering that the Van Gujjars’ estimates of the loans provided would suggest that the trader is owed over Rs 2 crore in that dera alone. But with the Van Gujjars surrounding me and their extreme fear of consequences, I could not challenge the lala’s claims.

Although the Van Gujjars still deeply identify with their transhumant lifestyle, many in the younger generation have started moving away from the milk economy. With barely enough money to survive, many Van Gujjars have to resort to selling their only source of income—their cattle. The significance of this cannot be understated.

The Van Gujjars consider their cattle a part of their family—each one is assigned a name, just like the children in the family, and their lives practically revolve around their cattle. An elderly Van Gujjar I stayed with last September told me that their daily schedule is based on the cattle. They wake up early morning to feed the cattle, take them to graze and rest in the afternoon when the cattle rests. The same routine is followed in the evening. Most Van Gujjars do not consume meat out of respect for their cattle, except one religious day of the year, on Eid Ul Azha, when it is obligatory to sacrifice and eat cattle for those who can afford it. “The festival is about sacrifice and we sacrifice our most prized possession on the day,” 70-year-old Noor Mohammad told me. To sell their cattle, then, is almost unimaginable within the community, and telling of the infeasibility of the new milk economy they find themselves trapped in.

For a little extra income, several young Gujjars, especially from the Gendi Khata and Pathri resettlements, also travel to the city to do menial labour jobs, often taking their friends and relatives from the jungle with them. Gulam Rasool said he did know how this cycle of debt and dependence will end but also blames the younger generation for spending too much and abandoning their minimalistic lifestyle. “They spend 200-300 rupees on mobile recharge every month,” he added. Hamja, who is 26 years old, observed that Van Gujjars were known to be well off in the bygone days. It is only recent decades that this downfall has come. “It all began when our sense of ownership of the jungle was attacked. We weren’t in charge of the jungle, and by extension, our lives anymore.”

Related Posts

A New Economy: How Van Gujjars in Uttarakhand are trapped in a cycle of debt and dependence

Sharafat Ali Kasana lost his father, Noor Deen, in 2002. Deen, the head of the household at the time, led his family and other Van Gujjars to the alpine mountains in the summer for their annual migration from the Rajaji forest in Uttarakhand. He died during this migration, and Kasana still regrets that his father was not cremated until the day after his death, because they could not find a suitable burial ground, shroud, or anyone to lead the cremation prayers. “That was the last time we migrated to the mountains,” Kasana recalled. Over the decades, as restrictions on the free movement of Van Gujjars grew, the community was forced to adapt their migratory patterns for the benefit of their cattle, but the change has come at a grave cost—a cycle of perpetual debt.

The Van Gujjars are a Muslim, semi-nomadic, pastoralist community of Gujjars (also spelled Gurjars) spread across the forests of Himachal Pradesh, Uttarakhand, Uttar Pradesh, and Jammu and Kashmir. Their primary occupation is rearing a breed of mountain buffaloes commonly known as Gojri. As a transhumant community, the Van Gujjars migrate to the alpine forests of the upper Himalayas in the summer, and return to the hilly terrain of the Shivalik forest, which now falls within the Rajaji National Park, in the winters. The main purpose of the Van Gujjar migration, as I previously reported, is to find grasslands for their cattle while allowing the jungles in the lower Himalayas to rejuvenate, grow, and heal after a season of grazing and lopping—a traditional and sustainable method of tree shedding practised by Van Gujjars, also known as “rotational grazing.”

To sustain themselves, the Van Gujjars would sell milk products to towns and villages along their route, and buy their essentials in return, traditionally engaging in a barter practice, which evolved into a cash transaction, but nonetheless forming a self-sufficient economy. For several generations, the Van Gujjars were involved in this trade. Kasana’s grandparents would freely graze and use other resources of the forest for themselves and their cattle. “It all began to change when our movement within the forests was restricted,” said Shamshad, a local Van Gujjar community leader. “Now the Van Gujjars simply cannot depend on forest resources for feeding out cattle and we’ve to buy cattle feed from markets.” As a result, in recent decades, their traditional lifestyle has come under threat.

With the forests declared as national parks and tiger reserves, and the expansion of tourism projects associated to them, the Van Gujjars lost much of the access to their grazing lands. Even with grazing permits, they continue to face hostility from forest officials. Now, with fewer places to graze their cattle, they must rely on expensive market supplements and bulk purchases of cattle feed, which force them to take loans from local milk traders. These traders exploit the Van Gujjars by paying them a low price for their milk, transforming the self-sufficient, mutually beneficial economy into one of debt and dependence. In the process, the Van Gujjars have lost autonomy over their produce, and struggle to preserve their traditional way of life, adapting to the challenges and economic pressures of modern development.

Years before Deen’s death, Kasana and others had begun contemplating stopping their alpine migration because of the increasing hostility and restrictions. But his community still migrates from the Rajaji and Shivalik forests to Khaddar Ka Tapu—the floodplain of the river Ganga—in the Bijnore district of Uttar Pradesh for three months every year. The Gojri buffaloes cannot survive the extreme summers of the lower Himalayas, which for the past several years has been witnessing extreme rises in temperatures causing forest fires. “Even if our buffaloes could survive the harsh summer, it is economically impossible for us to stay in the jungle during summers,” Kasana said.

The transformation of the Van Gujjar economy

Meer Hamja, the founder of Van Gujjar Tribal Yuva Sangathan—a youth organisation of Van Gujjars working towards achieving forest rights for the community—believes the erosion of their rights began five decades ago. “The whole process of categorisation of forests into sanctuaries, parks, and reserves begun in 1974,” Hamja said. “Several conservation committees were formed and the forest department began to vigilantly curtail our movement within the forest we have freely lived in since generations. Slowly, with time, less and less grazing grounds were made available to us, and our sense of ownership to the jungle began to erode as we simply couldn’t rely on the forests for our survival.”

Hamja, like Kasana, comes from one among the several dozen Van Gujjar families who still live in the Rajaji forest, in the lower foothills of Himalayas, encompassing the cities of Haridwar and Rishikesh. In 1992, following its designation as a national park, the Uttarakhand forest department relocated 1,300 families from the Motichur and Ranipur areas of Rajaji forest to Patri and Gendi Khata villages of Haridwar, just near the borders of Bijnore district of Uttar Pradesh. A Mongabay report noted that another 1,300-1,600 people were relocated from the forests but without lands, forcing them to build temporary shelters near river banks across the valleys of Haridwar and Rishikesh. Gulam Rasool, a 44-year-old Van Gujjar I met at Kasana’s dera, told me that his brother was allotted land in Gendi Khata but he was not, forcing him to seek shelter at various places temporarily, often at the mercy of fellow Gujjars.

All the Van Gujjars I spoke with said they used to go to the alpine forests in Uttarkashi and Tehri Garhwal for their annual migration in the summers, until they were abruptly prevented from taking their usual routes from within the forest. Rasool last went to the alpine bugyals (grasslands) two decades ago in the early 2000s. “The journey itself was hard enough as it was, but the restrictions and other issues made it a lot more difficult,” he said. “It was not worth it even for our cattle.”

The Van Gujjars’ old migratory routes, such as those followed by Deen until his death, would often take a month to complete. The journey was marked by open spaces and forests that the transhumant pastoralists would traverse using set, predetermined routes and timetables, halting at the common lands of several villages along the way. The villagers relied on the Van Gujjars for milk products, like butter and ghee, in the absence of commercial markets in the higher altitudes.

“Those were different days,” Hamja said. “The villagers used to wait for us not only for our milk products but to sell their grass to us. They’d also buy jhotas”— male buffaloes—“from us for breeding purposed and used to barter their beef cow to us in exchange of ghee. Moreover, when we left, our herds used to leave them a substantial amount of dung, which they would use as manure.” Meer described the relation as one of mutual dependence with the villagers. “Earlier both of us were the same. Both were poor.”

All of this changed with the formation of the Uttarakhand state in 2000, and the plethora of development projects that came in the newly-formed state. A 2011 research study, titled “Adaptation and Coexistence of Van Gujjars in the Forests: A Success Story,” argues that despite forest restrictions and diversions, “the Van Gujjars have proved to be resilient and have an intact social structures and mechanisms for mutual sharing of resources for sedentary purposes.” The researchers, Rubina Nusrat, BK Pattanaik and Nehal A Farooqui, note that the Himalayan states have undergone drastic infrastructure developments in recent decades for the purposes of tourism, hotels, road construction, hydropower plants, and more. For defence purposes alone, the study found, a total of 16,653 kilometres of metalled and 2,593 kilometres of non-metalled roads were constructed in the region. “As a result, the Van Gujjars have had to alter their migratory routes and face problems of livestock being killed on roads, thefts and a constant pressure to move,” the researchers wrote. “There are instances where animals die due to eating noxious weeds growing close to the roads on degraded land.”

These developmental projects also improved the socio-economic conditions of the villagers with whom the Van Gujjars used to trade. The higher altitude areas in the state with better road connectivity saw a boom in the tourism industry creating more economic opportunities for the villagers. “The villagers left their old jobs and became sahabs (bosses) who were disgusted by even looking at cow dung,” Hamja said. Aman Chechi, the current president of Van Gujjar youth group, echoed the organisation’s founder. “After the development drive, the places where we previously had our traditional migration trails had pakka roads built over it now,” he said. “Our resting places had become hotels or dumping grounds for those hotels. Our presence there was not a good look for the villagers now.”

In addition, the increasing restrictions of movement within the forests due to the notification of national parks and sanctuaries further exacerbated the struggle of the Gujjars in their migration. In the years that followed, the Van Gujjars sought to continue their annual migration to the alpine meadows, adapting to new routes along roads. To avoid the heavy traffic that makes the mountainous terrain perilous, they travelled mostly at night, resting during the day. However, this shift brought its own challenges. While they once relied on grazing grass provided by villagers along the way, they were now forced to purchase expensive food supplements from the market to sustain their cattle.

The traditional barter system, where they exchanged milk products for essentials, had largely collapsed, leaving them struggling to find new markets for their dairy produce. The journey became even more arduous during the scorching summer heat, as they constantly had to search for water sources and suitable resting spots for their caravan of people and livestock. These adjustments added layers of complexity to an already difficult migration. This meant that, due to limited resources, they were forced to reduce the number of stops they could make along the way, pushing themselves to complete the journey with minimal supplies and greater strain.

Eventually, most Van Gujjars in the Shivalik region abandoned migrating to the alpines for a much nearer and much shorter migration to Bijnore for three months every year. However, back in the lower Himalayas, when the Gujjars return from the migration, they find hard to access the grasslands even with grazing permits and continue to be harassed by the forest rangers. Limiting their access to the forest with no grasslands has forced the Gujjars to buy feed for their cattle from the market.

An economy of debt, dependence and exploitation

Today, almost all Van Gujjars almost entirely rely on market products to feed their cattle. “There are no grasslands available for us,” Kasana said. “We cannot lop the trees anymore. How are we going to feed our cattle if we do not buy it from the market? The three months in Bijnore is the only time we don’t have to buy feed for our cattle.”

The Van Gujjars mostly buy four types of cattle feed for their buffaloes—mustard khal, chokar (wheat bran), pural and bhoosa (wheat straw). In Kasana’s dera—a small cluster of huts, built using mud and tree branches—each family has an additional hut to store these supplements. Sharafat needs khal and chokar worth Rs 8,50,000 every year, along with pural and bhoosa worth Rs 3,00,000, to feed his herd of 30 cattle, eight of whom give milk. “We don’t have the money to buy for our requirements in bulk. We have to seek help from the lalas.”

The lalas are how Van Gujjars refer to the milk traders who buy the milk from them. While the Van Gujjars could previously sell the milk to the different villagers along the way, it is now the lalas who have monopolised the market and control all purchases. In fact, the milk traders from the nearby city of Rishikesh and Haridwar have a peculiar business relation with the pastoralists—they not only buy the milk, but also provide loans to the Van Gujjars to buy the food supplements for their cattle.

Since the Van Gujjars are no longer travelling through numerous villages during their migration, they need to sell their milk and milk products at a wholesale scale, which is not possible for the villagers living near the Van Gujjars. It is this gap in the market that the milk traders have exploited, and instead of paying the herders, the lalas claim that the cost of the milk is offset against the price of the cattle feed they source and provide to the Van Gujjars. What appears to be a routine business practice has trapped the Van Gujjars in a cruel cycle of debt, dependence and exploitation.

Kasana’s calculation of Rs 11,50,000 annually for his cattle feed is a rough estimate. In reality, he has never made these purchases. Instead, his lala gets the feed delivered to his dera as and when it is necessary, so the actual purchase is made by the lala. In return, Sharafat and other Van Gujjars have to sell their milk to these traders at a relatively cheaper price.

But the Van Gujjars are never paid the amount for the milk they sell to their lalas upfront. Kasana sells 30 litres milk per day at Rs 50 per litre, but he has never been paid the daily earnings of Rs 1,500 that he is due, which roughly amounts to a monthly income of Rs 45,000 that is denied to him. Instead, Kasana and all other Van Gujjars I interviewed usually ask their lalas for money every once a while if they need anything, who gives them a meagre sum between Rs 500–1000, twice or thrice every week, in order to buy essentials. The rest of the money owed to the Van Gujjars as payment for the milk is treated as a part of repayment for the dues owed to the lala for the cattle feed.

I asked dozens of Van Gujjars whether they had any idea of how much money they owed to their lala, or how much their lala owed to them, or any specifics of the transactions between the two parties. None of them knew about the particularities of the business, even though they were doing transactions for years. “Most of the Van Gujjars are illiterate and they never kept records of the transactions,” Hamja said. He explained how the lalas treat the payment for the cattle feed as a huge, unquantified loan offered to the Van Gujjars. Consequently, every supply of milk is treated as a small repayment of this supposed loan, and Van Gujjars are effectively kept trapped in bonded labour, dependent on the lalas for their cattle feed, for the money for essential commodities, and forced to provide the milk at low rates and unable to sell it to anyone else.

“Now the situation is such that they are so afraid of their lalas that they fear asking for details,” Hamja added. While Kasana described his financial situation, another Van Gujjar added, “The loan never gets repaid. I know not a single person here who isn’t in debt from the lala.” Yet, as Hamja described, the Van Gujjar refused to be identified by name, out of fear that the lala would punish him for it. “It is a good business but only for the lala,” he continued. “He buys cattle feed for dozens of families here worth crores every year and avails huge discount on that but our loan is set on the market price. In return, he gets cheaper milk from us and we barely get enough to survive.” Kasana added, “The only benefit we receive from this milk trade is that we get the milk for our tea at home for free.”

The fear among the Van Gujjars of lalas was palpable in all conversations. All the Van Gujjars I spoke to refused to share the contact details of their respective milk traders out of fear that any reporting on them would have grave consequences for their daily livelihood.

One cold November afternoon in the Rajaji forest, when I was speaking to a group of Van Gujjars at a dera, our conversation was interrupted by the loud honk of a mini truck. It was the lala for the entire dera. The truck stopped at the farthest hut, two men quickly stepped out, and transferred the milk from a container kept outside one of the huts in the dera, into a container in the truck. The two then drove to the next hut, and then the next one, until the milk traders had taken the milk from all the Van Gujjar homes in the dera—around 20–30 in total. The entire collection was completed in less than an hour, without any exchange about the payment for the milk the lalas were collecting.

I sought to speak to the traders, but the Van Gujjars were vehemently opposed to the idea. I had to repeatedly assure them that I would ask simple questions that would not adversely affect them and their livelihood. Several of them followed me to the lala and surrounded the two of us to hear our conversation.

“The Van Gujjars tell me that you loan them tens of lakhs every year for their cattle feed, and take their milk at lower price as a form of repayment,” I said. “I did calculation of the loans you give and the milk you get in return from this dera. Why are you in a loss-making business?”

“I am only helping the Van Gujjars,” the milk trader answered. The trader, who runs a large dairy shop in Rishikesh city and buys around 700 litres of milk every day from the Van Gujjars, added that he too, like the Van Gujjars, was earning little and struggling to survive. The claim is difficult to believe, considering that the Van Gujjars’ estimates of the loans provided would suggest that the trader is owed over Rs 2 crore in that dera alone. But with the Van Gujjars surrounding me and their extreme fear of consequences, I could not challenge the lala’s claims.

Although the Van Gujjars still deeply identify with their transhumant lifestyle, many in the younger generation have started moving away from the milk economy. With barely enough money to survive, many Van Gujjars have to resort to selling their only source of income—their cattle. The significance of this cannot be understated.

The Van Gujjars consider their cattle a part of their family—each one is assigned a name, just like the children in the family, and their lives practically revolve around their cattle. An elderly Van Gujjar I stayed with last September told me that their daily schedule is based on the cattle. They wake up early morning to feed the cattle, take them to graze and rest in the afternoon when the cattle rests. The same routine is followed in the evening. Most Van Gujjars do not consume meat out of respect for their cattle, except one religious day of the year, on Eid Ul Azha, when it is obligatory to sacrifice and eat cattle for those who can afford it. “The festival is about sacrifice and we sacrifice our most prized possession on the day,” 70-year-old Noor Mohammad told me. To sell their cattle, then, is almost unimaginable within the community, and telling of the infeasibility of the new milk economy they find themselves trapped in.

For a little extra income, several young Gujjars, especially from the Gendi Khata and Pathri resettlements, also travel to the city to do menial labour jobs, often taking their friends and relatives from the jungle with them. Gulam Rasool said he did know how this cycle of debt and dependence will end but also blames the younger generation for spending too much and abandoning their minimalistic lifestyle. “They spend 200-300 rupees on mobile recharge every month,” he added. Hamja, who is 26 years old, observed that Van Gujjars were known to be well off in the bygone days. It is only recent decades that this downfall has come. “It all began when our sense of ownership of the jungle was attacked. We weren’t in charge of the jungle, and by extension, our lives anymore.”

SUPPORT US

We like bringing the stories that don’t get told to you. For that, we need your support. However small, we would appreciate it.