In this essay, Anuja Jaiswal looks at the political and legal fallout of Yahya Jammeh’s regime and the constitutional crisis triggered by his refusal to leave office in 2017. Jaiswal examines how the civil society continues to seek justice for Jammeh’s overreaches, how it can impacted the fabric of Gambian society and what the way forward could look like.

Saul Ndow, a Gambian businessman, disappeared in April 2013. He was killed by military officers allegedly acting on behalf of President Yahya Jammeh. It took over three years for his family to learn the truth about his death. His daughter, Nana-Jo Ndow, launched the Jammeh2Justice campaign with other victims and founded the African Network Against Extrajudicial Killings and Enforced Disappearances (ANEKED).

Between 1994 and 2017, Yahya Jammeh used every tool at his disposal to entrench himself in power. He bent The Gambia’s state machinery to his will freely employing draconian tactics against civilians. Victims suffered arbitrary arrest and detentions, enforced disappearances, extrajudicial killings and torture, while their perpetrators thrived. In December 2016, when a new President Adama Barrow was elected to office, Yahya Jammeh’s refusal to concede the presidency triggered a constitutional crisis. On the ground, activists mobilized to defend the results, uniting under the umbrella of the #GambiaHasDecided movement while the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) threatened a military intervention. After 22 years of human rights violations, Jammeh finally left The Gambia in January 2017, fleeing to Equatorial Guinea. Although Jammeh was gone, his legacy remained in the form of a compromised state apparatus, eroded by over two decades of abuse, severely depleted public resources and an inestimable number of victims waiting for justice and redress.

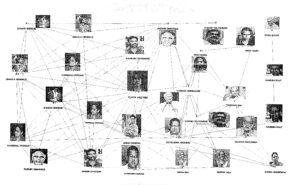

Immediately after Jammeh’s ousting, victims began organizing for justice, setting up the Gambian Center for Victims of Human Rights Violations. A coalition of national and international rights groups converged under the label Jammeh2Justice to gather victims’ accounts and build political pressure for criminal prosecutions. They were aware that a trial for Yahya Jammeh could take years to materialize yet were determined to seek justice. With a bottom-up approach, they worked to raise awareness about human rights violations and reach lesser known victims. The Center registered around 250 victims in October 2017 and the number rose to 1,000 by January 2018.

On the other hand, the Gambian government emphasized truth seeking and reconciliation. From the outset, the victims and the new government seemed to have different priorities. The government mandated a Truth, Reconciliation and Reparations Commission (TRRC), an independent truth seeking body to create a historical record of the human rights violations committed between 1994 and 2017, choosing to delay criminal prosecutions until after the Commission submitted their final report and recommendations. Although the Commission was tasked with identifying and recommending people for prosecution, it did not preclude the government’s ability and responsibility to carry out legal investigations. Moreover, not all victims required the Commission to establish the facts underlying their cases and many victims, Civil Society Organizations (CSOs) and intergovernmental bodies urged the Gambian government to implement the TRRC alongside criminal prosecution. The UN Working Group on Enforced or Involuntary Disappearances (WGEID) highlighted multiple times the importance of such synchronicity. Regardless, the government adopted a sequential approach.

Despite the government’s reluctance to pursue legal recourse, victims continued pushing for justice. Martin Kyere, the sole known survivor of the 2005 West African Migrants Massacre, where 59 migrants were forcibly disappeared and killed on Gambian soil, helped launch Jammeh2Justice Ghana. In May 2018, a joint investigation by TRIAL International and Human Rights Watch effectively tied Yahya Jammeh to the murders, refuting a 2008 UN-ECOWAS report that cleared him of responsibility. Calls for The Ghana Government to prosecute Jammeh intensified and victims urged Senegal and Togo, that also lost migrants, to join the movement. At the same time, the Gambian government was preoccupied with working out practicalities, such as choosing members and securing funds for the Commission.

The first public hearing of the TRRC took place on 7 January 2019, nearly two years after Yahya Jammeh’s departure. Every public testimony was broadcast and streamed live. By its conclusion in May 2021, the Commission had heard from 392 witnesses, including victims, perpetrators and experts. Former “Junglers” – a group of military officers who acted as Yahya Jammeh’s personal hit squad – narrated (and in some cases confessed to) multiple tortures, arbitrary detentions, enforced disappearances and extrajudicial killings allegedly carried out on Jammeh’s orders. Victims detailed the brutality of the April 2000 student protests, when security forces fired at unarmed students. Survivors and former employees disclosed how Yahya Jammeh allegedly raped and sexually assaulted multiple women. Former security officials revealed that the murder of 59 West African migrants was meticulously covered up, misleading the 2008 UN-ECOWAS investigation into clearing Yahya Jammeh of all responsibility. Lawyers outlined how the Gambian judiciary was systemically compromised by “mercenary judges,” allowing the State to wrongfully convict and disappear anyone considered an opponent.

For over two and a half years, the Gambian society was inundated with accounts of human rights violations. The continual discovery and spotlighting of past abuses enhanced the urgency of calls for justice even as TRRC hearings and recommendations were repeatedly postponed due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

*

Although the majority of the Junglers fled Gambia after Jammeh’s fall, at least six were taken into custody in 2017. In July 2019, former Junglers Malick Jatta, Omar “Oya” Jallow, Amadou Badjie and Pa Ousman Sanneh testified at the TRRC. They shocked the world with gruesome details of their involvement in numerous murders and enforced disappearances. A few days later, they were released from detention.

The decision to free them came to light in a leaked letter, plunging the country into a state of rage and confusion. Then Minister of Justice Abubacarr Tambadou assured victims that the release did not mean amnesty and that every decision was in their interest. He asked that victims give the Commission time to make their recommendations. Despite promises that the release was conditional, many found the idea of letting confessed killers back into civil society troubling. Some were afraid of encountering them, while others feared that their release would cause unrest and violence.

Abubacarr Tambadou highlighted that the Junglers were truthful before the Commission and insisted that he could not keep them in detention without charges. However, two other Junglers who had testified, Ismaila Jammeh and Alieu Jeng, stayed in detention ostensibly for lying before the Commission. The visible difference implied that honest testimony would lead to freedom whilst lying meant imprisonment thus setting an unclear standard.

The Junglers’ release was made even more confusing by parallel events. In early July 2019, Yankuba Touray, Minister of Local Government in the Jammeh regime’s early days, refused to testify at the TRRC. He was subsequently charged with contempt and arrested. A few days later, the Ministry of Justice charged him with the murder of Ousman Koro Ceesay. After two years of trial, he was sentenced to death. Many touted Yankuba Touray’s conviction as a momentous example of long overdue justice. However, it also raised the question of why the State could not pursue similar charges in the Junglers’ cases.

Based on the contrasting treatment of Malick Jatta, Ismaila Jammeh and Yankuba Touray, it seemed that telling the truth set you free, lying kept you in detention and refusing to testify led to prosecution, but the rationale behind these decisions remained unexplained. The Executive Secretary of the TRRC Baba Galleh Jallow affirmed that the Commission was not consulted on the matter.

In January 2022, former Junglers Saul Badjie, Landing Tamba and Musa Badjie were arrested upon their return from Equatorial Guinea, but the Ministry of Justice did not press any charges against them. A month later, High Court judge Zainab Jawara ordered their release, asserting that continuing to detain them without charge was a violation of their fundamental rights. In late March, Ismaila Jammeh and Alieu Jeng were released on the same grounds.

In September 2021, ahead of the general elections in December, Yahya Jammeh’s former party, the Alliance for Patriotic Reorientation and Construction (APRC), announced a coalition with incumbent President Adama Barrow’s National People’s Party (NPP). The agreement between the parties was not made public, but the APRC’s loyalty to Jammeh suggested impunity was on the table. The APRC had spent years calling for Yahya Jammeh’s return – with amnesty and all the benefits afforded to a head of state. Party leader Fabakary Tombong Jatta publicly declared that the TRRC Final Report – the document the government had spent years telling victims to wait for before prosecutions – should be “put in a wastepaper basket.” The NPP issued a statement denying that Jammeh’s return was part of the deal, but Ousman Jatta, deputy party-leader of the APRC, refuted it a few days later.

After years of being told to wait for justice and suspecting that Barrow’s government lacked the political will to pursue it, news of the coalition elicited anger and disappointment. Activist Madi Jobarteh called it “the worst betrayal on earth.” Victims and CSOs immediately mobilized condemning impunity. After re-election, Adama Barrow assured the victims that justice would be done. The TRRC released its much awaited final report in late 2021, which included the notable recommendation to prosecute Yahya Jammeh for multiple human rights violations and crimes against humanity. The report named 69 others for prosecution. Several of them – including those accused of crimes against humanity – applied for amnesty.

Shockingly, in March 2022, the TRRC Amnesty committee recommended Sanna Sabally, Yahya Jammeh’s former vice-Chairman, for amnesty, citing his honest testimony and cooperation with the Commission. The committee report claimed that Sabally’s crimes precede the Rome Statute which “cannot be applied retroactively.” Sanna Sabally was instrumental in helping Jammeh seize power and complicit in many human rights violations, especially during the 11 November 1994 attacks. The Commission found Sanna Sabally responsible for torture, assault, arbitrary detention and the extrajudicial killings of at least 11 soldiers. The Victims’ Center and CSOs immediately issued a statement disavowing the recommendation, highlighting that Sanna Sabally’s victims were not consulted before the Committee made their decision. The statement also emphasized: “We would like to remind the Commission that victims are not incidental, but bona fide stakeholders with a key role to play and the right to participate in the transitional justice process, including any amnesty process. This has been reiterated on several occasions, yet the Commission and the government continue to disregard the victims over and over again.”

While victims continue to seek accountability for the abuses they suffered under a brutal regime, the new government lacks the resources and political will to pursue it. Victims are a vital part of The Gambia’s transitional justice process. The Government’s choice to delay prosecutions was worsened by the lack of transparency and shared ownership of decisions. By delaying justice, the Government is creating long-term consequences for society.

I spoke to Nana-Jo and Sirra Ndow, ANEKED’s country director, about the current situation in The Gambia. Yahya Jammeh ruled for 22 years. For many young people, his version of The Gambia is all they have known. Nana-Jo views accountability as an “absolutely crucial” step in rebuilding society. As The Gambia did not emerge from a civil war or major post-election violence, it is seemingly easy to think that all is well once the dictator is ousted. Accountability, however, ensures that perpetrators understand the consequences of their actions and, more importantly, it signals that such atrocities are unacceptable going forward.

Sirra explains that Gambian society and culture are already primed towards impunity: a broken justice system actively deters people from seeking accountability while the expenses and time to pursue a case are a serious obstacle. The importance of forgiveness in Christianity and Islam, The Gambia’s major faiths, also makes seeking justice and holding onto past wrongs, however heinous, look morally dubious. Sirra emphasizes that the culture of impunity existed before Yahya Jammeh and persists even now, so the country needs to reverse the pattern to avoid becoming vulnerable to similar events in the future. Delaying prosecutions has further entrenched impunity. Victims are discouraged from pursuing justice; Nana-Jo points out that there was widespread outrage when the first Junglers were released in 2019, but the recent releases sparked a much smaller outcry.

*

Yusupha Mbye testified during Session 8 of the TRRC. On 10 April 2000, he had joined fellow students at a protest. He was 17 at the time. The Police Intervention Unit (PIU) officers released teargas and chased them. News of students being shot spread through the crowd – suddenly, paramilitary officers opened fire. Yusupha Mbye woke up in excruciating pain. A bullet had struck his neck and lodged in his spine. He was completely paralyzed. He spent the next decade struggling to get adequate healthcare and redress for his injuries, with no aid or even acknowledgement from the Government.

19 years later, during his testimony, Yusupha Mbye expressed anger that the people who did this to him never faced any punishment. He emphasized that reconciliation was not possible without justice and questioned why prosecutions were not implemented alongside the TRRC. Several witnesses echoed his feelings.

Considering the multitude of violent incidents that occurred during Yahya Jammeh’s reign, victims have been awaiting justice for decades. Multiple perpetrators, including several Junglers, have returned to civil society and are likely running into their victims. This is a situation that is bound to explode. As Nana-Jo put it, you cannot ignore the past: “If you do not deal with it, it will come back and slap you in the face.”

As Gambian society is in transition, continuing to push for reconciliation without justice only deepens the divide between people and the State. Sirra points out that “reconciliation and forgiveness are in [Gambia’s] DNA, […] the missing element is accountability.”

Setting truth commissions immediately after military dictatorships or armed conflicts actively precludes the possibility of judicial recourse, sometimes resulting in zero prosecutions. For example, the truth-seeking exercise in Liberia was followed by no prosecutions within the country – the only prosecutions took place outside Liberia. A similar pattern is emerging in The Gambia (with the exception of Yankuba Touray), exacerbated by the fact that many recommended for prosecution live outside the country and multiple perpetrators currently work with Gambian security agencies.

Three alleged perpetrators were apprehended abroad. Former Minister of Interior Ousman Sonko is under investigation in Switzerland and former Junglers Michael Correa and Bai Lowe were indicted in the United States and Germany respectively. However, Nana-Jo emphasizes that victims cannot constantly rely on other governments for justice. Local ownership is crucial in transitional justice. To move forward as a nation, Gambians need to see prosecutions within their own borders.

Related Posts

Auto Queens: Circles of Labor, Form, and Survival

Lav Diaz on How ‘Magellan’ Subverts the Colonial Gaze

Saul Ndow, a Gambian businessman, disappeared in April 2013. He was killed by military officers allegedly acting on behalf of President Yahya Jammeh. It took over three years for his family to learn the truth about his death. His daughter, Nana-Jo Ndow, launched the Jammeh2Justice campaign with other victims and founded the African Network Against Extrajudicial Killings and Enforced Disappearances (ANEKED).

Between 1994 and 2017, Yahya Jammeh used every tool at his disposal to entrench himself in power. He bent The Gambia’s state machinery to his will freely employing draconian tactics against civilians. Victims suffered arbitrary arrest and detentions, enforced disappearances, extrajudicial killings and torture, while their perpetrators thrived. In December 2016, when a new President Adama Barrow was elected to office, Yahya Jammeh’s refusal to concede the presidency triggered a constitutional crisis. On the ground, activists mobilized to defend the results, uniting under the umbrella of the #GambiaHasDecided movement while the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) threatened a military intervention. After 22 years of human rights violations, Jammeh finally left The Gambia in January 2017, fleeing to Equatorial Guinea. Although Jammeh was gone, his legacy remained in the form of a compromised state apparatus, eroded by over two decades of abuse, severely depleted public resources and an inestimable number of victims waiting for justice and redress.

Immediately after Jammeh’s ousting, victims began organizing for justice, setting up the Gambian Center for Victims of Human Rights Violations. A coalition of national and international rights groups converged under the label Jammeh2Justice to gather victims’ accounts and build political pressure for criminal prosecutions. They were aware that a trial for Yahya Jammeh could take years to materialize yet were determined to seek justice. With a bottom-up approach, they worked to raise awareness about human rights violations and reach lesser known victims. The Center registered around 250 victims in October 2017 and the number rose to 1,000 by January 2018.

On the other hand, the Gambian government emphasized truth seeking and reconciliation. From the outset, the victims and the new government seemed to have different priorities. The government mandated a Truth, Reconciliation and Reparations Commission (TRRC), an independent truth seeking body to create a historical record of the human rights violations committed between 1994 and 2017, choosing to delay criminal prosecutions until after the Commission submitted their final report and recommendations. Although the Commission was tasked with identifying and recommending people for prosecution, it did not preclude the government’s ability and responsibility to carry out legal investigations. Moreover, not all victims required the Commission to establish the facts underlying their cases and many victims, Civil Society Organizations (CSOs) and intergovernmental bodies urged the Gambian government to implement the TRRC alongside criminal prosecution. The UN Working Group on Enforced or Involuntary Disappearances (WGEID) highlighted multiple times the importance of such synchronicity. Regardless, the government adopted a sequential approach.

Despite the government’s reluctance to pursue legal recourse, victims continued pushing for justice. Martin Kyere, the sole known survivor of the 2005 West African Migrants Massacre, where 59 migrants were forcibly disappeared and killed on Gambian soil, helped launch Jammeh2Justice Ghana. In May 2018, a joint investigation by TRIAL International and Human Rights Watch effectively tied Yahya Jammeh to the murders, refuting a 2008 UN-ECOWAS report that cleared him of responsibility. Calls for The Ghana Government to prosecute Jammeh intensified and victims urged Senegal and Togo, that also lost migrants, to join the movement. At the same time, the Gambian government was preoccupied with working out practicalities, such as choosing members and securing funds for the Commission.

The first public hearing of the TRRC took place on 7 January 2019, nearly two years after Yahya Jammeh’s departure. Every public testimony was broadcast and streamed live. By its conclusion in May 2021, the Commission had heard from 392 witnesses, including victims, perpetrators and experts. Former “Junglers” – a group of military officers who acted as Yahya Jammeh’s personal hit squad – narrated (and in some cases confessed to) multiple tortures, arbitrary detentions, enforced disappearances and extrajudicial killings allegedly carried out on Jammeh’s orders. Victims detailed the brutality of the April 2000 student protests, when security forces fired at unarmed students. Survivors and former employees disclosed how Yahya Jammeh allegedly raped and sexually assaulted multiple women. Former security officials revealed that the murder of 59 West African migrants was meticulously covered up, misleading the 2008 UN-ECOWAS investigation into clearing Yahya Jammeh of all responsibility. Lawyers outlined how the Gambian judiciary was systemically compromised by “mercenary judges,” allowing the State to wrongfully convict and disappear anyone considered an opponent.

For over two and a half years, the Gambian society was inundated with accounts of human rights violations. The continual discovery and spotlighting of past abuses enhanced the urgency of calls for justice even as TRRC hearings and recommendations were repeatedly postponed due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

*

Although the majority of the Junglers fled Gambia after Jammeh’s fall, at least six were taken into custody in 2017. In July 2019, former Junglers Malick Jatta, Omar “Oya” Jallow, Amadou Badjie and Pa Ousman Sanneh testified at the TRRC. They shocked the world with gruesome details of their involvement in numerous murders and enforced disappearances. A few days later, they were released from detention.

The decision to free them came to light in a leaked letter, plunging the country into a state of rage and confusion. Then Minister of Justice Abubacarr Tambadou assured victims that the release did not mean amnesty and that every decision was in their interest. He asked that victims give the Commission time to make their recommendations. Despite promises that the release was conditional, many found the idea of letting confessed killers back into civil society troubling. Some were afraid of encountering them, while others feared that their release would cause unrest and violence.

Abubacarr Tambadou highlighted that the Junglers were truthful before the Commission and insisted that he could not keep them in detention without charges. However, two other Junglers who had testified, Ismaila Jammeh and Alieu Jeng, stayed in detention ostensibly for lying before the Commission. The visible difference implied that honest testimony would lead to freedom whilst lying meant imprisonment thus setting an unclear standard.

The Junglers’ release was made even more confusing by parallel events. In early July 2019, Yankuba Touray, Minister of Local Government in the Jammeh regime’s early days, refused to testify at the TRRC. He was subsequently charged with contempt and arrested. A few days later, the Ministry of Justice charged him with the murder of Ousman Koro Ceesay. After two years of trial, he was sentenced to death. Many touted Yankuba Touray’s conviction as a momentous example of long overdue justice. However, it also raised the question of why the State could not pursue similar charges in the Junglers’ cases.

Based on the contrasting treatment of Malick Jatta, Ismaila Jammeh and Yankuba Touray, it seemed that telling the truth set you free, lying kept you in detention and refusing to testify led to prosecution, but the rationale behind these decisions remained unexplained. The Executive Secretary of the TRRC Baba Galleh Jallow affirmed that the Commission was not consulted on the matter.

In January 2022, former Junglers Saul Badjie, Landing Tamba and Musa Badjie were arrested upon their return from Equatorial Guinea, but the Ministry of Justice did not press any charges against them. A month later, High Court judge Zainab Jawara ordered their release, asserting that continuing to detain them without charge was a violation of their fundamental rights. In late March, Ismaila Jammeh and Alieu Jeng were released on the same grounds.

In September 2021, ahead of the general elections in December, Yahya Jammeh’s former party, the Alliance for Patriotic Reorientation and Construction (APRC), announced a coalition with incumbent President Adama Barrow’s National People’s Party (NPP). The agreement between the parties was not made public, but the APRC’s loyalty to Jammeh suggested impunity was on the table. The APRC had spent years calling for Yahya Jammeh’s return – with amnesty and all the benefits afforded to a head of state. Party leader Fabakary Tombong Jatta publicly declared that the TRRC Final Report – the document the government had spent years telling victims to wait for before prosecutions – should be “put in a wastepaper basket.” The NPP issued a statement denying that Jammeh’s return was part of the deal, but Ousman Jatta, deputy party-leader of the APRC, refuted it a few days later.

After years of being told to wait for justice and suspecting that Barrow’s government lacked the political will to pursue it, news of the coalition elicited anger and disappointment. Activist Madi Jobarteh called it “the worst betrayal on earth.” Victims and CSOs immediately mobilized condemning impunity. After re-election, Adama Barrow assured the victims that justice would be done. The TRRC released its much awaited final report in late 2021, which included the notable recommendation to prosecute Yahya Jammeh for multiple human rights violations and crimes against humanity. The report named 69 others for prosecution. Several of them – including those accused of crimes against humanity – applied for amnesty.

Shockingly, in March 2022, the TRRC Amnesty committee recommended Sanna Sabally, Yahya Jammeh’s former vice-Chairman, for amnesty, citing his honest testimony and cooperation with the Commission. The committee report claimed that Sabally’s crimes precede the Rome Statute which “cannot be applied retroactively.” Sanna Sabally was instrumental in helping Jammeh seize power and complicit in many human rights violations, especially during the 11 November 1994 attacks. The Commission found Sanna Sabally responsible for torture, assault, arbitrary detention and the extrajudicial killings of at least 11 soldiers. The Victims’ Center and CSOs immediately issued a statement disavowing the recommendation, highlighting that Sanna Sabally’s victims were not consulted before the Committee made their decision. The statement also emphasized: “We would like to remind the Commission that victims are not incidental, but bona fide stakeholders with a key role to play and the right to participate in the transitional justice process, including any amnesty process. This has been reiterated on several occasions, yet the Commission and the government continue to disregard the victims over and over again.”

While victims continue to seek accountability for the abuses they suffered under a brutal regime, the new government lacks the resources and political will to pursue it. Victims are a vital part of The Gambia’s transitional justice process. The Government’s choice to delay prosecutions was worsened by the lack of transparency and shared ownership of decisions. By delaying justice, the Government is creating long-term consequences for society.

I spoke to Nana-Jo and Sirra Ndow, ANEKED’s country director, about the current situation in The Gambia. Yahya Jammeh ruled for 22 years. For many young people, his version of The Gambia is all they have known. Nana-Jo views accountability as an “absolutely crucial” step in rebuilding society. As The Gambia did not emerge from a civil war or major post-election violence, it is seemingly easy to think that all is well once the dictator is ousted. Accountability, however, ensures that perpetrators understand the consequences of their actions and, more importantly, it signals that such atrocities are unacceptable going forward.

Sirra explains that Gambian society and culture are already primed towards impunity: a broken justice system actively deters people from seeking accountability while the expenses and time to pursue a case are a serious obstacle. The importance of forgiveness in Christianity and Islam, The Gambia’s major faiths, also makes seeking justice and holding onto past wrongs, however heinous, look morally dubious. Sirra emphasizes that the culture of impunity existed before Yahya Jammeh and persists even now, so the country needs to reverse the pattern to avoid becoming vulnerable to similar events in the future. Delaying prosecutions has further entrenched impunity. Victims are discouraged from pursuing justice; Nana-Jo points out that there was widespread outrage when the first Junglers were released in 2019, but the recent releases sparked a much smaller outcry.

*

Yusupha Mbye testified during Session 8 of the TRRC. On 10 April 2000, he had joined fellow students at a protest. He was 17 at the time. The Police Intervention Unit (PIU) officers released teargas and chased them. News of students being shot spread through the crowd – suddenly, paramilitary officers opened fire. Yusupha Mbye woke up in excruciating pain. A bullet had struck his neck and lodged in his spine. He was completely paralyzed. He spent the next decade struggling to get adequate healthcare and redress for his injuries, with no aid or even acknowledgement from the Government.

19 years later, during his testimony, Yusupha Mbye expressed anger that the people who did this to him never faced any punishment. He emphasized that reconciliation was not possible without justice and questioned why prosecutions were not implemented alongside the TRRC. Several witnesses echoed his feelings.

Considering the multitude of violent incidents that occurred during Yahya Jammeh’s reign, victims have been awaiting justice for decades. Multiple perpetrators, including several Junglers, have returned to civil society and are likely running into their victims. This is a situation that is bound to explode. As Nana-Jo put it, you cannot ignore the past: “If you do not deal with it, it will come back and slap you in the face.”

As Gambian society is in transition, continuing to push for reconciliation without justice only deepens the divide between people and the State. Sirra points out that “reconciliation and forgiveness are in [Gambia’s] DNA, […] the missing element is accountability.”

Setting truth commissions immediately after military dictatorships or armed conflicts actively precludes the possibility of judicial recourse, sometimes resulting in zero prosecutions. For example, the truth-seeking exercise in Liberia was followed by no prosecutions within the country – the only prosecutions took place outside Liberia. A similar pattern is emerging in The Gambia (with the exception of Yankuba Touray), exacerbated by the fact that many recommended for prosecution live outside the country and multiple perpetrators currently work with Gambian security agencies.

Three alleged perpetrators were apprehended abroad. Former Minister of Interior Ousman Sonko is under investigation in Switzerland and former Junglers Michael Correa and Bai Lowe were indicted in the United States and Germany respectively. However, Nana-Jo emphasizes that victims cannot constantly rely on other governments for justice. Local ownership is crucial in transitional justice. To move forward as a nation, Gambians need to see prosecutions within their own borders.

SUPPORT US

We like bringing the stories that don’t get told to you. For that, we need your support. However small, we would appreciate it.