The politics of biography: Ram Guha’s concluding Gandhi bio is a familiar exercise in deifying him, reinforcing inequality — A book review

The celebrity Indian historian’s refusal to triangulate Gandhi’s own recollections and memoirs and the sources contemporaneous to his times with more recent scholarship leaves us with a biography intellectually thin and long on anecdote. Gandhi’s uncritical internalization of the separation between the political and the social on which the book rests impoverishes Guha’s analysis of both Gandhi and his foremost intellectual and political adversaries like Jinnah and Ambedkar. In the end, an adroit strategy of guilt-by-association clears the space for Guha the moderate biographer to consolidate Gandhi’s towering place in history.

Every conservative Hindu house is a South Africa (a domain of apartheid) for a poor untouchable who is still being crushed under the heels of Hindu imperialism.

—Balwant Singh, An untouchable in the IAS.[efn_note] Balwant Singh, An Untouchable in the IAS (Saharanpur, n.d.) page 224-227, quoted in Gyanendra Pandey, A History of Prejudice (Cambridge University Press, 2013), page 70.

… even after sixty years of constitutional and legal support there is still … discrimination against Dalits … The only parallel [is] apartheid.

—Prime Minister Manmohan Singh.[efn_note] Indian Prime Minister Manmohan Singh quoted in Rupa Viswanath, The Pariah Question: caste, religion and the social question in modern India (Columbia University Press, 2014), page 21.

On 22 September 1932, the Dalit leader B. R. Ambedkar met Mohandas Gandhi in Yerwada Jail in Pune, Maharashtra. Gandhi was into the third day of his fast unto death against the British colonial administration’s Communal Award that created separate electorates for Muslims, Sikhs, and the “Depressed Classes” (as Dalits were then termed). Gandhi’s objection was not to the awarding of separate electorates to Muslims and Sikhs but to Dalits. Since the Depressed Classes totaled about 50 million or approximately 20 percent of India’s population at this time, their recognition as a distinct or separate category would severely compromise Gandhi’s, and the Congress Party’s, claim to speak for all, or at least the vast majority of, Indians. While the separate electorate would greatly strengthen Dalits in their effort to redress their horrendous socio-economic status, one that had endured for centuries if not millennia, Gandhi was against such a political solution to what he regarded as a social or even a moral problem. He considered Dalits to be Hindu and his preference was for ‘Harijan uplift’ or social reform—changing the minds and hearts of Caste Hindus about untouchability. According to the media at the time, the nation was in a frenzy as Gandhi’s health was deteriorating fast. The pressure on Ambedkar to “save the life of the Mahatma” by giving up the separate electorate the Dalits had been awarded, and to settle for a diluted version of it, can only be imagined.

At one point in their negotiations in Yerwada, Gandhi said to Ambedkar, “You are born an untouchable but I am an untouchable by adoption. And as a new convert, I feel more for the welfare of the community than those who are already there.” Ramachandra Guha, Gandhi: The Years that Changed the World, 1914-1948 (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2018), page 417. All future references to this work will just list the page number in parenthesis rather than author, title, and book. Picture, if you will, President Lyndon Johnson telling Martin Luther King Jr. during the mid-1960s that though he was not black, as someone successfully chaperoning the Civil Rights Act and the Voting Rights Act through the US Congress at that very moment, he (Johnson) felt more for the welfare of African-Americans than King possibly could, for after all the latter’s blackness was merely an accident of birth.

Picture, if you will, President Lyndon Johnson telling Martin Luther King Jr. during the mid-1960s that though he was not black, as someone successfully chaperoning the Civil Rights Act and the Voting Rights Act through the US Congress at that very moment, he (Johnson) felt more for the welfare of African-Americans than King possibly could, for after all the latter’s blackness was merely an accident of birth.

The disbelief and outrage that the latter hypothetical example would create has to be contrasted with the absence of any real outrage, then or now, at the audacity of Gandhi’s statement to Ambedkar in real life. This absence of outrage is a consequence of the deification of Mohandas Gandhi to “Mahatma”—besides indexing the powerlessness of Dalits. In the second of his two-volume biography of Gandhi, Ramachandra Guha perpetuates this deification at over a thousand pages. Guha’s biography is chronologically structured, moving from the pivotal years of 1913-14 when Gandhi went back to India from South Africa, traversing the familiar triad of Champaran-Kheda-Ahmedabad, on to Rowlatt and Non-Cooperation, through the Round Table Conferences of the early 1930s and thereafter Quit India, Partition, and martyrdom at the hands of a right-wing Hindu assassin. Throughout, the biography is marked by three prominent characteristics.

First, there is a persistent tendency to mine the archive for quotes from various interlocutors (mostly western and white, predominately English and American) ranging from celebrities and politicians to journalists and obscure autodidacts. For the most part, these nuggets praise (and occasionally vilify) Gandhi or demonstrate his endearing, if also already well-known, eccentricities. In this regard, Guha’s biography is evocative of Richard Attenborough’s movie Gandhi (1982) where his life is narrated through a series of encounters with whites—starting with the Rev. C. F. Andrews and General Smuts in South Africa, and thereafter with assorted colonial officials, journalists, judges, and acolytes down the years, ending with the Life magazine’s photojournalist Margaret Bourke-White. Each of these white interlocutors serves as a foil, propels the story through time, and translates or “explains” Gandhi and India to a non-Indian world. As an Anglophone movie about an Indian leader targeting a western Anglo-American audience, such a racial structuring made commercial sense. And it paid off: not only did Gandhi become one of the biggest grossing films of all time, it swept the Oscars and renewed Gandhi’s status as Mahatma for younger generations and across a larger section of the world than ever before. This similarity of narrative structures raises the question: who is the target audience for Guha’s book? One could argue it seeks to solidify Gandhi as Mahatma within a liberal, white public sphere internationally and an Indian middle class of largely upper-caste provenance distributed between the nation and its diaspora. The locus of enunciation is not so much a scholarly one as it is journalistic, and the audience is only tangentially academia.

Secondly, Guha’s biography, despite its humongous bulk, is rarely intellectually taxing as it’s not about ideas as much as it is about personalities. The reading is fast as the work moves chronologically and descriptively, framed as encounters between Gandhi and various allies, antagonists, and ashramites. These are related in a chatty style that elevates personality over principle and does not delve into the complexity of issues that divided Gandhi from many around him. Not unlike the movie, Jinnah comes across as vain, ambitious and obstreperous rather than someone with a different vantage on nationalism from Gandhi or the Congress. Ambedkar is shown as a prickly personality who resented Gandhi’s popularity and was unwilling to kowtow to his leadership, as distinct from someone whose understanding of caste and democracy was of a different order—not degree—from most nationalists. This reduction of substantive differences on caste, race, class, nationalism, gender, history, religion, and civilization to the domain of personality is accompanied by a strategy wherein Guha himself rarely disparages Jinnah or Ambedkar. Rather, he does so by citing a seemingly unbiased or neutral voice from the archive ventriloquizing that view.

And thirdly, the biography’s overwhelming reliance on sources contemporary to the years it covers (1914-48), and especially Gandhi’s own self-exculpatory renditions of events, gives it a strangely freeze-dried flavor. It allows Guha to not engage with rich veins of scholarship in fields such as history, political science, and biography that analyze Gandhi and his contemporaries through renewed eyes and a wider range of sources. Guha’s defense of his approach (mentioned in the context of a discussion of whether separate electorates for Muslims, granted as early as 1909, laid the ground for the later Partition of the subcontinent) is: “I have my own answers to these (admittedly) important questions, but this is not the place to offer them. The biographer’s task is to document what happened at the time, not to pose counterfactuals” (page 811).

This reduction of the “biographer’s task” to a sort of Rankean historical reportage (“what happened at the time”) is a choice that Guha makes, not something intrinsic to the genre of biography itself, and there is a political import to this choice. As we see below, well substantiated historical documentation regarding key events in Gandhi’s life that run contrary to his recollections or Guha’s deific narrative cannot be ignored or brushed under the carpet through a professed disinclination for “posing counterfactuals.” This scholarship requires a serious reappraisal of Mohandas Gandhi, to make a more balanced and informed judgement about the man and his actions then and their implications now—and that is surely part of the brief for any biographer? Guha’s refusal to triangulate Gandhi’s own recollections and memoirs and the sources contemporaneous to his times with more recent scholarship renders his biography intellectually thin: it reduces Gandhi’s encounters with his political, moral, and ethical adversaries and issues to matters of personality (jealousy, rivalry, prickliness, etc.) rather than engaging them in terms of their historical and political substance.

In this review, I focus on two themes. One, Guha’s depiction of the formative influence of South Africa on Gandhi’s politics and ethics. And, two, the differences between Gandhi and Ambedkar on caste, Dalits, and the nation. Focusing on these two themes—race and caste—allows us to see how works like Guha’s are central to the reproduction of Gandhi as Mahatma but obscure our understanding of Gandhi the man.

Whitewashing South Africa

At various points in his book, Guha repeats claims that can no longer be sustained, viz., that Gandhi’s South African years (1893 to 1914) were spent fighting for the rights of “Indians” in that country, that the South African prelude ended with Gandhi perfecting his technique of non-violent “satyagraha,” and that he left that country on a high note having led a successful strike by miners and plantation workers in late 1913 and early 1914 culminating in an agreement that secured their victory. Works by, among others, Maureen Swan, Kathryn Tidrick, Joseph Lelyveld, and especially two recent books by South African scholars, Ashwin Desai and Goolam Vahed, most of which Guha inexplicably ignores or deals with perfunctorily, paint a very different picture of Gandhi in South Africa.

The following sentences are typical of Guha on Gandhi’s politics in South Africa:

“He had been the unquestioned leader of the small Indian community…” (page 3);

“he moved from lawyering to activism, leading campaigns … against racial laws that bore down heavily on Indians” (page 4);

“… he had fought for the rights of plantation workers” (page 43);

“In South Africa, Gandhi’s first struggles against racial discrimination…” (page 93);

“In November 1913, he had led a slow, peaceful and yet spectacular march of several thousand Indians in Natal, who defied racial laws by crossing provincial boundaries into the Transvaal and courting arrest. By marching and sleeping in the open, and cooking their own food, and thus voluntarily inflicting suffering on themselves, the satyagrahis could draw attention to, and garner support for, their cause” (page 207);

“From 1893 to 1914, he had fought steadily for greater rights for Indians in South Africa” (page 628, all emphases mine).

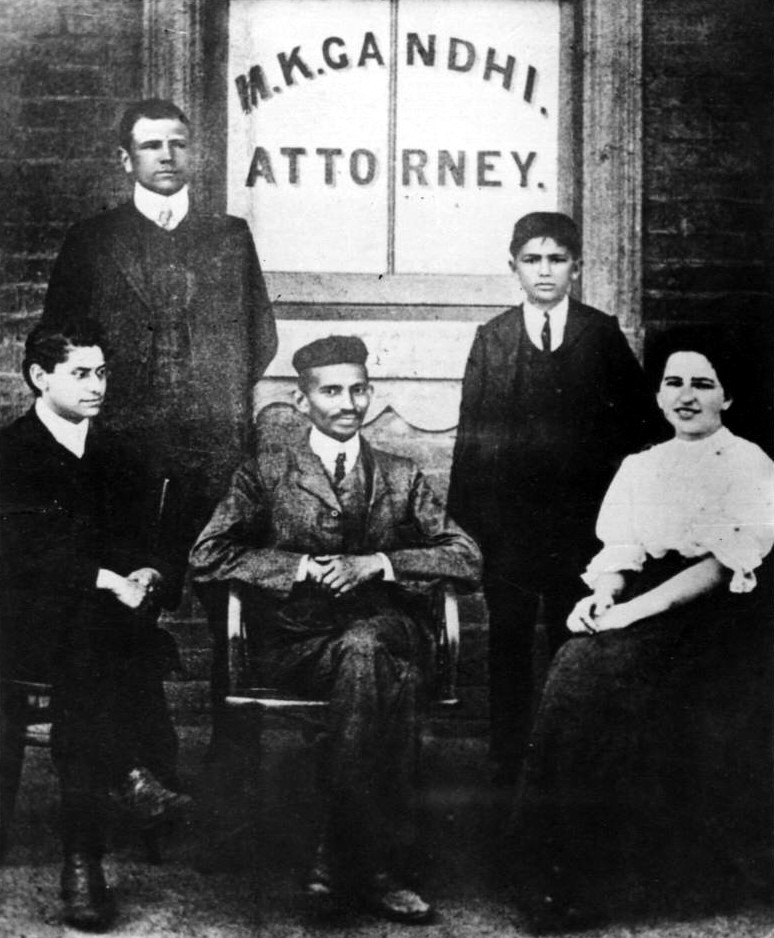

Gandhi went to South Africa as a lawyer representing a Muslim merchant, and his main qualification was his fluency in both English and Gujarati as well as his training in English law. (Gandhi would describe his years in South Africa as a “self-imposed exile” (page 516). He had tried and failed to launch a career as a lawyer in India after his return from England and went to South Africa for economic reasons. Endowing that decision to seek employment abroad with the halo of “exile”—even with the qualifier “self-imposed”—also seems disingenuous.) The category “Indian” as used by Guha in many of the quotes above is misleading. Gandhi represented the small mercantile and professional community of Indians in South Africa: they were the only “Indians” he was concerned with for nearly all his time in that country. He made it clear in all his petitioning to South African authorities that he held no brief for the vast majority of Indians in South Africa: indentured laborers who worked in the plantations and mines, or those who had recently come out of their servitude but chose to stay on in that country and were part of a growing underclass there.

Gandhi’s views about indentured laborers were identical to caste Indian views of Dalits back home that, similarly, blamed the victim. The only group even further down the ladder of inferiority in Gandhi’s view was native Africans whom he referred to as “kaffirs” throughout his time in South Africa. Gandhi’s views about these ex- and indentured Indians were indistinguishable from the worst racial stereotypes entertained about them by whites: he considered them dirty, untrustworthy, infantile, and prone to drunkenness, adultery, crime, and sloth. He regarded their benighted condition as moral failings and, owing to sins committed in past lives, as distinct from their being virtually slaves in a settler colony. His views about indentured laborers in other words were identical to caste Indian views of Dalits back home that, similarly, blamed the victim. The only group even further down the ladder of inferiority in Gandhi’s view was native Africans whom he referred to as “kaffirs” throughout his time in South Africa.

Gandhi interacted mainly—almost exclusively—with a small group of white friends and colleagues in South Africa. They shared his view about coolie Indians and kaffir Africans, and that Indians like himself were racially and civilizationally far closer to whites than they were to either of those two. Guha devotes a fair amount of space to Gandhi’s interactions with these individuals even after he returned to India (Kallenbach, Polak, and others) but makes little mention of their racial ordering of the world. While Guha acknowledges that Gandhi’s interactions with black South Africans was non-existent, he never makes explicit that the situation was not very different when it came to his interactions with the ex- and indentured laborers. Rather, the loosely used category “Indian” papers over class and caste distinctions that were very important to Gandhi at this time, and gives the erroneous impression that he fought against the white settler regime for the rights and prospects of all Indians there as distinct from the tiny class fraction he mostly represented.

Gandhi twice served as head of a volunteer “Indian” stretcher corps that he himself proposed and mobilized: on the first occasion on the side of the British against the Afrikaners in the Boer War (1899-1902), and the second in 1913 on the side of the white Anglo-Boer regime against Zulus when the latter rebelled against the Union of South Africa, which had forced their alienation from their own lands. On both occasions, Gandhi sought favours for his constituency of upper class and caste Indians by proving his loyalty to white empire—literally over black bodies. On both occasions, as well, the stretcher corps was seen by him as a consolation prize—he would much rather have served as an armed combatant to prove the worthiness (manliness) of Indians like him, and their parity with the colonizer in killing native Africans. The centrality of violence as a means to human being, and its role in the racial hierarchy in Gandhi’s thinking at this time, was no aberration. When he stopped in England in 1914 on his way back to India and as the Great War looked imminent, he threw himself into efforts to mobilize volunteers for that conflict to the amazement of many who had taken his many pronouncements on non-violence at his word. Violence as a cleansing and annealing force in attaining manhood or nationhood resurfaces repeatedly in his writings thereafter, recurs in his praise for Adolf Hitler as late as 1939, and informs his ardent desire to die a violent death at the hands of an assassin rather than of illness or old age.

Many years ago, Ashis Nandy had commented astutely on the centrality of violence to Gandhi’s ethics and politics (see his essay “Final Encounter: the politics of Gandhi’s assassination” in his At the Edge of Psychology: essays in politics and culture).[efn_note] Delhi: Oxford University Press, 1980: 73-87. [/efn_note] This centrality has been further explored by Faisal Devji in his recent The Impossible Indian: Gandhi and the Temptation of Violence.[efn_note] Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press, 2012. [/efn_note] What these works, alongside others mentioned in note 4, would seem to necessitate is a reappraisal of the ethics of Gandhian non-violence. While considerations of space preempt a fuller analysis here, at minimum it appears that (a) Gandhi was quite enamored of peoples, races, castes and nations that had the capacity and the will to inflict violence on others; (b) that he never quite outgrew his admiration for violence as an index of strength and masculinity even into his final years; and (c) non-violence was a moral, cleansing and ethical force only when exercised by the strong, that is, upper castes and superior races, and not when exercised by those in positions of inferiority or weakness.

This imbrication of the morality of violence with the hierarchies of caste (and race) is something that Ambedkar alluded to in his many engagements with Gandhi, and is something that awaits fuller historical and intellectual investigation. I merely note it here at this moment.

Violence as a cleansing and annealing force in attaining manhood or nationhood resurfaces repeatedly in his writings thereafter, recurs in his praise for Adolf Hitler as late as 1939, and informs his ardent desire to die a violent death at the hands of an assassin rather than of illness or old age. Later, in his memoir on his South African years, Gandhi would make much of the impact the slaughter of the Zulus had upon his conscience—something Lelyveld (2011: 71) bluntly describes as a “retrospective tidying up” but which Guha sees as proof of Gandhi’s overcoming his racism. Yet, in South Africa, he constantly and obsequiously entreated the regime for equal opportunity for Indians like him to join combat against the outgunned Zulus. The casualties from the “war” to suppress them were so lopsided that even a sanguinary imperialist and white supremacist like Winston Churchill, at that time a young reporter, filed back to London objecting to the indiscriminate slaughter. Gandhi repeatedly admired the bloodlust of English soldiers, something he saw as explaining, even justifying, their rule over much of the world including India. Incredibly, at this time Gandhi was preaching non-violent resistance to the soon-to-be-killed Zulu chief Bhambatha and his followers in his newspaper columns while simultaneously pleading with the white regime to allow Indians like himself to ditch the stretchers and take up arms against the Zulu.

The depth and mendacity of Gandhi’s racism, his casteist and patronizing attitude towards the ex- and indentured Indians, and his unceasing effort to ingratiate himself with whites as a civilizational equal, are all muted in Guha’s biography. Instead, South Africa is inscribed as a prolepsis for Gandhi’s struggle against colonialism and caste inequality after his return to homeland.

A large part of the case for regarding South Africa as the crucible for Gandhi’s technique of non-violent resistance or satyagraha comes down to his final year there. In late 1913, the country was rocked by one of the most militant and sweeping movements for economic justice by indentured laborers who went on a strike that paralyzed the country. The strike spread from the plantations and mines to include both black and white working classes and across a variety of other sectors of the economy. This was the only struggle in his 21 years in South Africa in which Gandhi allied himself with the laboring classes of Indians in that country, and its allegedly successful resolution enabled him to return to India as a leader of consequence.

Gandhi sought favours for his constituency of upper class and caste Indians by proving his loyalty to white empire—literally over black bodies. It’s worth noting that a few months prior to this strike in late 1913, the mercantile class that had constituted his core constituency in South Africa had a falling out with Gandhi over his vacillating leadership and propensity to package craven compromises as tactical victories in his parleys with the regime. In other words, Gandhi’s brief flirtation with the class politics of indentured labor came only after having burned his bridges with the ‘better’ class of Indians he had proudly represented until then. Even so, Gandhi made it clear that the striking laborers should not make common cause with the Africans, many of whom were on strike as well. By this time, he was mentally packing his bags for India as his South African sojourn seemed to be reaching a political and economic dead end for him. This would also be the moment when Gandhi’s politics would take on a more explicitly Hindu coloration, something held in check so long as his paymasters were Muslim merchants.

Gandhi’s final months in South Africa were not quite the militant crescendo followed by triumphant farewell that Guha portrays. Firstly, there is ample evidence that far from leading this struggle, Gandhi was caught by surprise at the rapidity with which the strikes spread through the plantations and mines, as well as the extent of their violent militancy. As Desai and Vahed note in their book: “Clearly Gandhi did not envisage the scale of involvement of the miners. It was, after all, not a constituency he had worked with or on behalf. He told the Rand Daily Mail on October 23, 1913, that he had ‘never expected that the response would be so spontaneous, sudden and large.” [efn_note] Desai and Vahed, 2015: 150. [/efn_note] Gandhi repeatedly exhorted laborers to moderation, to respect the property of plantation and mine owners, and to refrain from violence even in face of the most extreme provocation by police or the armed foremen. The solicitude Gandhi shows for the property of mine and plantation owners in an economy built on African and Indian slave labor is really quite remarkable, and it’s a solicitousness that would mark his politics to the very end of his life.

Secondly, Guha makes much of the fact that the miners slept out in the open and established community kitchens to feed themselves, and argues this was a part of their training as satyagrahis inspired by Gandhi. Yet, as Desai and Vahed note, indentured laborers in South Africa had a long history of resistance, both in its everyday forms and with occasional irruptions into violence and strikes against what was slavery by another name. This tradition of resistance predated Gandhi’s arrival in their midst and would endure long after he had left. There is not much evidence that they saw themselves as satyagrahis pursuing his plans, besides Gandhi’s own self-aggrandizing claims in this regard and now cemented into history by repetition in various hagiographies.

In a passage emblematic of the distance that separated Gandhi’s politics from their militancy, Desai and Vahed note:

“Most accounts of the strike reinforce the Gandhi-centric story by focusing on the ‘epic’ march across the border of Natal and the Transvaal. But the strikes spread across caste, class and gender lines; engulfed large parts of the province; and was often outside the control of Gandhi and his coterie of leaders … The methods of strikers in coastal areas were frequently far removed from the notion of passive resistance, the dominant discourse in which the strike is narrated. Whatever Gandhi’s original intentions, phases of the strike were anything but passive. This part of the story has not been given sufficient prominence in the historiography. This may partly be a result of basing the narrative around Gandhi, which is understandable given the reliance on his autobiographical writings and the works of his associates. The focus on Gandhi may also have been prompted by his subsequent role in the anti-colonial struggle in India, or the power of satyagraha (passive resistance) as a moral force in ‘our times.’ As our narrative reveals, strikers were not necessarily imbued with the spirit of satyagraha. This is not to discount the massive influence of Gandhi, but rather to write back into history the fertile texture of the historical experience of the indentured, who dug deep into memories of past collective and individual resistances and ‘invisible’ networks to mount a serious challenge to authority and, for a short while, caused panic in the ranks of employers. The strike spread to the coastal areas in spite of, not because of, Gandhi who wanted to contain it. … There were experiments with armed struggle. Sticks and knife caches were hidden along roads, cane fields were torched, policemen ambushed, white farmers besieged and taken hostage. So threatening did these attacks become that reinforcements were sent from as far afield as the Eastern Cape. While organization and coordination was poor, and repression brutal, the passive resistance campaign was, in large swathes of the former Natal, an uprising, and a fairly militant one at that” (Desai and Vahed, 2010, page 399).

Amidst this militancy, Gandhi’s concerns were, as would be typical of him till his dying day, about the inviolable rights of the propertied. As Desai and Vahed note in their more recent (2015) book:

“Gandhi stated that strikers were urged to leave the mines because it was ‘improper to live on mine rations when we don’t work’. This must have sounded hollow to mine workers. Their owners oversaw a brutal labour regime enforced by white foremen who often acted as gangsters. Miners had risked everything in taking on their employers, yet Gandhi was preaching in moralistic tones about taking rations from owners who had taken their very blood” (page 154).

Gandhi wrote of this movement at the height of its militancy that “they struck not as indentured laborers but as servants of India. They were taking part in a religious war.” In his recollection, many of the common slogans raised during the protests were in the vein of “Victory to Ramachandra,” “Victory to Dwarakanath,” and “Vande Mataram.” It is noteworthy that after having spent two decades denying the Indian-ness of these laborers, Gandhi now elevated their national identity over class. Further, freed of his Muslim sponsors, he misrecognizes them as participating in a “religious war.”

Gandhi’s equation of these “servants of India” with Hindu “religious warriors” and his explicit disavowal of any notion of class identity in their politics add up to a vexing brew. It indexed an understanding of the Indian nation as one inextricable from a Hindu ethos, and a distaste for political action motivated by resistance to economic or class exploitation. His politics revealed a highly top-down and pedagogical approach to leadership even as those he claimed to represent frequently outflanked him. As Lelyveld (2011: 128) notes in regard to his equation with the Indian underclass in South Africa: “he could speak of them and for them, but mostly, he wasn’t speaking to them.”

To Guha, Gandhi’s patronizing comments about indentured laborers, about their docility and simplicity, for example, are regrettable aberrations in one of the first successful experiments in satyagraha. But in light of evidence presented in the works cited here, they are not aberrations but constitutive of his political ethos and method, then and later after his return to India. Guha makes much of a few pronouncements by Gandhi in the last three decades of his life that may be interpreted as a revision of his earlier racism and casteism, and he touts the fact that Black American civil rights activists visited him to pay their respects during these decades as further proof of such a transformation. Yet, looking at Gandhi’s vacillations on a host of matters pertaining to race, caste, gender, and class right until his death, Guha’s case does not sound very persuasive.

Between them these works that Guha chooses to largely elide also incontrovertibly establish that: one, the final settlement that Gandhi negotiated with Gen. Smuts—the Indian Relief Act—riding on the extraordinary militancy of the strikes was one that failed to deliver on most of their demands and over the longer run may have even worsened their situation; two, Gandhi consistently presented himself to the white settler state as a moderate whose usefulness lay in dampening the threat of militant labor to a racialized political economy; three, that his status in their eyes as an equal or worthy adversary mattered more to him than delivering to the people he ostensibly represented; and, four, that the chain of farewell ceremonies in the weeks prior to his leaving South Africa on 18 July 1914 were marked by profuse thanks extended to him by white property owners and racist state officials—and a sense of betrayal on the part of indentured laborers whose militancy he was riding, not to mention the complete invisibility of any indigenous Africans.

Contrary to claims by Guha that Gandhi gradually evolved into a patriot and an anti-imperialist by the end of his South African sojourn, Desai and Vahed (2015: 216) note, “the core of Gandhi’s life in South Africa” lay in repeatedly demonstrating his “loyalty as an Indian to Empire … the fact that Gandhi’s loyalty to Empire was emphasized time and again during his farewell tour by his well-wishers, which he affirmed, points in the opposite direction.”

South Africa did represent in many ways the crucible for Gandhi’s politics in the 34 years that followed his departure from there but not in the sense that Guha suggests. It is not the perfection of strategies of satyagraha or the ability to mobilize large numbers of people into disciplined acts of resistance that shines through his South African years but rather his troubling views about race and caste, his desire to ingratiate himself with those in power, his fear of militant labor, and the centrality of violence to his understanding of manhood and nationhood. Constraints of space don’t allow a discussion on two other salient matters in this regard: Gandhi’s deeply problematic understanding of gender, and the sources of Gandhi’s conviction that he was a chosen one, someone destined to become a Mahatma over his lifetime. (The works of Maureen Swan and (especially) Kathryn Tidrick cited above are very insightful in the latter regard.) By eschewing engagement with these recent works, Guha’s biography replicates Gandhi’s own exculpatory and selective retrospection of this period.

The political is more than the personal

Guha indexes the shift through this sentence: “From social reform, Gandhi plunged straight into politics.” This seemingly innocuous sentence sequesters untouchability in the realm of “social reform” and equates “politics” with the anticolonial movement and in so doing replicates a division central to Gandhi and the national movement at large.On page 125 of his biography, after describing Gandhi’s views on untouchability and his call for a cautious and incremental reform of the practice, Guha moves on to his speech to the Congress party on 30 December 1920, on the non-cooperation resolution. Guha indexes the shift through this sentence: “From social reform, Gandhi plunged straight into politics.” This seemingly innocuous sentence sequesters untouchability in the realm of “social reform” and equates “politics” with the anticolonial movement and in so doing replicates a division central to Gandhi and the national movement at large. The main import of this distinction was a deferral of thorny or divisive issues like caste, class, and gender inequality to a post-independence order in which they could be redressed under self-government while focusing on anticolonialism in the meanwhile.

While there is a case to be made (one that has been made ad nauseam) that prioritizing national independence over “divisive” social issues was tactically astute, the uncritical internalization of the separation between the political and the social on which it rests impoverishes Guha’s analysis of both Gandhi and his foremost intellectual and political adversaries like Jinnah and Ambedkar. In a brief review, I can do no more than illustrate how this sequestering of caste/untouchability to the domain of social reform, and reserving the political for the anticolonial struggle, contributes to Guha’s thin and personalistic analysis of the encounter between Gandhi and Ambedkar.

In closely argued texts with slightly different inflections, Anupama Rao and Aishwary Kumar detail the ethical consequences of a separation of the social and the political, something that cut to the heart of Ambedkar’s view of caste society and the impossibility of democracy therein.[efn_note] Anupama Rao, The Caste Question (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2009); Aishwary Kumar, Radical Equality: Ambedkar, Gandhi and the Risk of Democracy (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2015). [/efn_note] Ambedkar disagreed with Gandhi’s view that a politics bereft of religion was no politics at all, and his dictum that Hinduism like any other religion ought to be assessed by what was best about it rather than its worst aspects (like Untouchability.) Instead, Ambedkar saw the Hindu religion as an ossified sediment or residue, consecrated by passage of time and habit, of an originary violence that hierarchized society into the twice-born and the rest, a hierarchy now manifest as an unthinking set of discriminatory practices, rituals, customs, and taboos. The birth of any legal order was marked not by a social contract willingly entered into by putative equals; rather every legal order originated in violence, by the monopolization of power by a fraction of society which thereafter sanctified and reproduced this monopoly on power through the realms of the social and the religious. To uncritically separate the social from the political, then, was to further mystify the illegal, immoral, and violent foundations of any given order, and to partake in its further entrenchment as sacred custom.

If such an originary violence followed by the willed amnesia of ritual was common to every politico-legal order, India and Hindu society, Ambedkar argued, would appear to be its apotheosis. No other society divided man from man with the degree of inhumanity as did caste and nowhere else were the principles of hierarchy encased in so much arcane ritual. Caste militated against any possibility of egalitarian fraternity because it kept each endogamous jati in conflictual wariness of those below or on a par with itself, while aspiring to join those above through mimesis. Hence, in Ambedkar’s powerful metaphor, Hindus were denizens of a multistory building bereft of stairs or elevators. Further, about 50 million of them, Dalits, were consigned to an airless basement and whose mere touch was regarded as polluting.

The maintenance of this order required not merely an elaborate set of quotidian practices centered on distinctions of purity and pollution but, more importantly, continuous and egregious violence against anyone, especially the Dalit, who sought to renegotiate their ascribed status. Violence, then, was not an aberration in this religio-legal order; it was constitutive of it and central to its reproduction. It served as a deterrent to any who dare even imagine altering it, let alone act on that imagination. It was this peculiar status of the Dalit being outside the caste system, but through his negative presence integral to its constitution and reproduction, that occasioned Ambedkar’s insight that Dalits were “a part apart” of the Hindu fold.

The key difference here between Gandhi and Ambedkar is the latter’s understanding that the “political” was inextricable from the “social,” that the latter was the site of everyday practices sanctified by tradition and custom that sought to erase the memory—but replicate the violence—of the establishment of this unequal political, legal, or moral order. To “reform” this through a focus on the social abstracted from the political through changing the minds and hearts of Caste Indians, as Gandhi would have it, was to misunderstand the braided inextricability of the two domains. Reforming caste in this way would be impossible and immeasurable because it focused on everyday practices while leaving the structures of domination intact, hence Ambedkar’s clarity that caste needed to be annihilated, not reformed.

This was also the reason why Ambedkar saw the award of a separate electorate to the Dalits in 1932 as a huge opportunity to leverage the political to effect structural change. His bitterness at having succumbed to Gandhi’s passive-aggressive blackmail in this regard would only increase over the remainder of his life. The Poona pact that he was forced to accept diluted the reserved electorate to merely reserved constituencies in which only Dalit candidates could contest but whose electorate remained general. He correctly anticipated that such ostensibly Dalit representatives may end up as nothing more than moderates chosen for their pliancy to Caste Hindu leaders from the main political parties rather than for their autonomy. The extent of Ambedkar’s bitterness about Gandhi’s fast that blackmailed him into giving in to the Poona pact can be gleaned from this interview he gave to the BBC in the final months of his life.

As Ambedkar more than once acidly noted, he was not interested in temple entry or inter-dining qua themselves but only because they were public spaces and that meant everyone in a democratic and egalitarian society must have equal access to them. More than temple entry or inter-dining, Dalit demands focused on equal access to economic and educational opportunities and to real, consequential, or substantive political power. The Gandhian strategy of “Harijan uplift” further made it very clear that the purpose of this effort was the willed self-transformation of the Caste Hindu, as an act of moral self-making on his part. The Dalit was merely the mute and unthinking floormat for Gandhi’s ethical calisthenics in this regard.

A second important consequence of prioritizing the “anticolonial” political over the “divisive” social was that it wrote the likes of Ambedkar and Periyar into the category of the loyalist. In charging them with falling prey to the “divide and rule” tactics of the British colonial regime, this viewpoint assumed what had to be proven in the first place: that there existed a unity, a national social, to begin with, that was threatened by division and the machinations of an alien regime. Guha proffers Ambedkar’s joining the Viceroy’s Executive Council during the years of World War II, when Gandhi and other nationalist leaders were in prison, as a reason for their alienation from each other. Yet, from Ambedkar’s perspective, nothing about the status of the Untouchable in India gave him any reason to think he or the Dalits were included in the nation to begin with.

Caste Hindus began to count Dalits as part of their religion only in the early 20th century when it was becoming evident that power was going to be gradually devolved to the various communities of India on the basis of their size or percentage of the overall population. Number gained a new and unprecedented salience from about this time. Enfolding the Dalit into Hinduism and resisting their conversion to other faiths suddenly became important to the upper caste-dominated nationalist movement.

Caste Hindu solicitation for the Dalit—evident in the “shuddhi” (reconversion) movement in the early 20th century for instance—was instrumental and expedient, and emerged not out of any sense of fraternity with them. Thirdly, Gandhian tactics of “Harijan uplift” may have appeared innovative and cut from the larger cloth of his eclectic inspirations ranging from Tolstoy and Thoreau to the Bhagavad Gita and his mother. This eclecticism has been much ballyhooed and praised. But, as the recent work of Rupa Viswanath (see note 2) on the Madras presidency shows, in actuality, they were remarkably similar to Caste Hindu and Christian missionary attempts to address the “pariah problem” in the Madras presidency of the late 19th century. Pariahs at that time were not regarded as a part of the Hindu fold and frequently not even regarded as Tamil. Yet, their captive and coerced labor constituted the foundation of both the Raj’s land revenue collection and the wealth of landed upper castes. In seeking to ameliorate the condition of pariahs, the colonial administration and Christian missionaries could not in any way alter the political economy of agrarian servitude or bond slavery upon which it ultimately rested. To do so would both antagonize landed upper castes and adversely impact land revenue. Predictably then, solutions to the “pariah problem” in the Madras Presidency rapidly devolved into reforming their alleged propensity to drink, their lack of cleanliness, their violent disposition, and a familiar litany of subaltern sins.

Viswanath uses the term “spiritualization of caste” to describe the eschewal of substantive solutions such as land redistribution, release from bonded labor, home ownership, or access to education as solutions to the “pariah problem” and focus instead on their cleanliness, drunkenness, sloth, and criminality as impediments to their progress. It is precisely such a willed ignorance of the political economy of servitude and a leap to addressing their alleged moral deficits that characterized Gandhi’s politics towards coolies in South Africa and that he now continued in India on the Dalit question. In other words, the continuity in Gandhi’s politics from South Africa to India lay not in satyagraha or strategies of non-violent resistance but in consistently deflecting the focus from material, class, and caste inequalities to moral and spiritual uplift and reform that essentially blamed the victim and reposed faith in the morals and values of the oppressor.

The rich and textured reading of the encounter between Gandhi and Ambedkar, between Caste Indians and Dalits, enabled by Kumar, Rao, and Viswanath (and there are many more such works) stand in sharp contrast to the anemic and personalistic account in Guha. To give a flavor of his take on the matter, consider these examples:

“He (Ambedkar) saw no further future for himself in Congress, where—like everyone else in that organization—he would have to subordinate himself to Gandhi. So he decided to work outside and even in opposition to it” (page 292).

“Having worked for decades for the same cause, Gandhi was patronizing towards someone he saw as a fresh convert, a johnny-come-lately, whereas Ambedkar was in fact an ‘untouchable’ who had experienced acute discrimination himself. Gandhi’s tone offended Ambedkar, souring the relationship at the start” (page 376).

“Of Gandhi’s long-standing commitment to ending untouchability, there could be no question. Even so, this moving account of how he had arrived at this decision was marred by the use of that unfortunate adjective, ‘helpless’. It sounded patronizing, robbing ‘untouchables’ of agency, of being able to articulate their own demands and grievances. This was precisely the kind of attitude that Ambedkar was protesting against” (page 416).

“Had Ambedkar been less independent-minded, he would have either joined the Congress or taken a secure, well-paying job in the colonial administration. But in the former case, he knew he would have to play second-fiddle to Gandhi, while in the latter he would not be free to express his views. In charting his own path, Ambedkar had come into conflict with the country’s major political party and even with senior leaders of his own Depressed Classes” (page 419).

“Ambedkar’s dislike for Gandhi was intense” (page 757).

Such quotes are emblematic of Guha’s thin understanding of the issues that divided Gandhi and Ambedkar in terms of personal rivalry and the latter’s thwarted ambition. Yet, as the extended discussion above suggests, the two men entertained vastly different conceptions of the nation, of democracy and egalitarianism, and their differences were deep and substantive. Guha’s avoidance of much of the recent literature on such matters, as in his neglect of works on the South African Gandhi, leaves us with a biography long (very long) on anecdote and the bon mot but superficial in its understanding of the life of its protagonist and the depth and complexity of his various encounters with the others of his time.

Of Mahatmas and moderation

A critical component of Guha’s credibility is his self-fashioning as an impartial and balanced biographer who abjures the extremism of both left and right. He rightly lambastes the pamphleteering pseudohistory of someone like Arun Shourie for its rendition of Ambedkar as a British stooge[efn_note] See Arun Shourie, Worshipping False Gods (New Delhi: Harper Collins, 2012). [/efn_note] but follows that by describing Arundhati Roy as Shourie’s left-wing counterpart for her recent work on Gandhi and Ambedkar. Roy’s work—incorporating as it does precisely the literature on Gandhi in South Africa that Guha chooses to ignore and in conversation with a growing public sphere of Dalit intellectuals and their assessments of Gandhi—is of a different order from that of Shourie.[efn_note] See Arundhati Roy, “Introduction” in B. R. Ambedkar, Annihilation of Caste: the annotated, critical edition (Original: 1936; London: Verso, 2016) as well as Arundhati Roy, The Doctor and the Saint: Caste, Race, and the Annihilation of Caste, the debate between B. R. Ambedkar and M. K. Gandhi (Haymarket Books, 2017).[/efn_note]

In contrast to Guha, who avers that even if Gandhi may have been racist towards blacks in South Africa or not adequately empathetic to the situation of Dalits soon after his return to India, his public pronouncements on race and caste over the last two decades of his life show that he had overcome his racism and casteism, Roy, following on the lines of much of the academic scholarship on Gandhi in recent decades, demonstrates that his politics retained an inordinate and baffling belief in the sanctity of social and racial hierarchy, showed a stubborn deference to the rights of the propertied over that of the underclasses, and remained deeply patronizing and suspicious of any signs of autonomy or initiative on the part of the subaltern classes. Roy’s work, while hardly the first to do so, is also important in the linkages it traces between the limits of Gandhian politics on issues of social inequality during the nationalist movement and the contemporary status of Dalits in India. That is to say, Roy’s work is attentive to the historical consequences of privileging the political (anti-colonial) over the social (anti-caste) that Guha uncritically glides past. His equation of Shourie’s work with that of Roy serves to discredit both and position them at opposite and extreme ends of a spectrum, while he himself occupies the moderate middle ground.

Guha’s work adds a scholarly heft to this deification of Gandhi and there is little doubt that his biography will find its place on many a bookshelf as the authoritative source on the life and times of the Mahatma. Those looking for a more intellectually challenging, historically accurate and less adulatory appraisal of Mohandas Gandhi will not find it here. In similar vein, one of Ambedkar’s many excoriations of Gandhi for his inability to comprehend the Dalit question is juxtaposed by Guha to a racist rant against Gandhi and Indians in general by Winston Churchill. The implied equation of a Dalit leader and intellectual with a white war criminal and imperialist is sutured by the phrase “while Ambedkar attacked Gandhi, in India, others were attacking him abroad” (page 662).

This adroit strategy of guilt-by-association clears the space for Guha the moderate biographer to consolidate Gandhi’s towering place in history. Gandhi-as-icon has increasingly come to stand for a free-floating and politically vacuous commitment to peaceful, non-violent change, especially within a self-professed liberal public sphere both internationally and among middle class Indians. Guha’s work adds a scholarly heft to this deification of Gandhi and there is little doubt that his biography will find its place on many a bookshelf as the authoritative source on the life and times of the Mahatma. Those looking for a more intellectually challenging, historically accurate and less adulatory appraisal of Mohandas Gandhi will not find it here.

Related Posts

The politics of biography: Ram Guha’s concluding Gandhi bio is a familiar exercise in deifying him, reinforcing inequality — A book review

The celebrity Indian historian’s refusal to triangulate Gandhi’s own recollections and memoirs and the sources contemporaneous to his times with more recent scholarship leaves us with a biography intellectually thin and long on anecdote. Gandhi’s uncritical internalization of the separation between the political and the social on which the book rests impoverishes Guha’s analysis of both Gandhi and his foremost intellectual and political adversaries like Jinnah and Ambedkar. In the end, an adroit strategy of guilt-by-association clears the space for Guha the moderate biographer to consolidate Gandhi’s towering place in history.

Every conservative Hindu house is a South Africa (a domain of apartheid) for a poor untouchable who is still being crushed under the heels of Hindu imperialism.

—Balwant Singh, An untouchable in the IAS.[efn_note] Balwant Singh, An Untouchable in the IAS (Saharanpur, n.d.) page 224-227, quoted in Gyanendra Pandey, A History of Prejudice (Cambridge University Press, 2013), page 70.

… even after sixty years of constitutional and legal support there is still … discrimination against Dalits … The only parallel [is] apartheid.

—Prime Minister Manmohan Singh.[efn_note] Indian Prime Minister Manmohan Singh quoted in Rupa Viswanath, The Pariah Question: caste, religion and the social question in modern India (Columbia University Press, 2014), page 21.

On 22 September 1932, the Dalit leader B. R. Ambedkar met Mohandas Gandhi in Yerwada Jail in Pune, Maharashtra. Gandhi was into the third day of his fast unto death against the British colonial administration’s Communal Award that created separate electorates for Muslims, Sikhs, and the “Depressed Classes” (as Dalits were then termed). Gandhi’s objection was not to the awarding of separate electorates to Muslims and Sikhs but to Dalits. Since the Depressed Classes totaled about 50 million or approximately 20 percent of India’s population at this time, their recognition as a distinct or separate category would severely compromise Gandhi’s, and the Congress Party’s, claim to speak for all, or at least the vast majority of, Indians. While the separate electorate would greatly strengthen Dalits in their effort to redress their horrendous socio-economic status, one that had endured for centuries if not millennia, Gandhi was against such a political solution to what he regarded as a social or even a moral problem. He considered Dalits to be Hindu and his preference was for ‘Harijan uplift’ or social reform—changing the minds and hearts of Caste Hindus about untouchability. According to the media at the time, the nation was in a frenzy as Gandhi’s health was deteriorating fast. The pressure on Ambedkar to “save the life of the Mahatma” by giving up the separate electorate the Dalits had been awarded, and to settle for a diluted version of it, can only be imagined.

At one point in their negotiations in Yerwada, Gandhi said to Ambedkar, “You are born an untouchable but I am an untouchable by adoption. And as a new convert, I feel more for the welfare of the community than those who are already there.” Ramachandra Guha, Gandhi: The Years that Changed the World, 1914-1948 (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2018), page 417. All future references to this work will just list the page number in parenthesis rather than author, title, and book. Picture, if you will, President Lyndon Johnson telling Martin Luther King Jr. during the mid-1960s that though he was not black, as someone successfully chaperoning the Civil Rights Act and the Voting Rights Act through the US Congress at that very moment, he (Johnson) felt more for the welfare of African-Americans than King possibly could, for after all the latter’s blackness was merely an accident of birth.

Picture, if you will, President Lyndon Johnson telling Martin Luther King Jr. during the mid-1960s that though he was not black, as someone successfully chaperoning the Civil Rights Act and the Voting Rights Act through the US Congress at that very moment, he (Johnson) felt more for the welfare of African-Americans than King possibly could, for after all the latter’s blackness was merely an accident of birth.

The disbelief and outrage that the latter hypothetical example would create has to be contrasted with the absence of any real outrage, then or now, at the audacity of Gandhi’s statement to Ambedkar in real life. This absence of outrage is a consequence of the deification of Mohandas Gandhi to “Mahatma”—besides indexing the powerlessness of Dalits. In the second of his two-volume biography of Gandhi, Ramachandra Guha perpetuates this deification at over a thousand pages. Guha’s biography is chronologically structured, moving from the pivotal years of 1913-14 when Gandhi went back to India from South Africa, traversing the familiar triad of Champaran-Kheda-Ahmedabad, on to Rowlatt and Non-Cooperation, through the Round Table Conferences of the early 1930s and thereafter Quit India, Partition, and martyrdom at the hands of a right-wing Hindu assassin. Throughout, the biography is marked by three prominent characteristics.

First, there is a persistent tendency to mine the archive for quotes from various interlocutors (mostly western and white, predominately English and American) ranging from celebrities and politicians to journalists and obscure autodidacts. For the most part, these nuggets praise (and occasionally vilify) Gandhi or demonstrate his endearing, if also already well-known, eccentricities. In this regard, Guha’s biography is evocative of Richard Attenborough’s movie Gandhi (1982) where his life is narrated through a series of encounters with whites—starting with the Rev. C. F. Andrews and General Smuts in South Africa, and thereafter with assorted colonial officials, journalists, judges, and acolytes down the years, ending with the Life magazine’s photojournalist Margaret Bourke-White. Each of these white interlocutors serves as a foil, propels the story through time, and translates or “explains” Gandhi and India to a non-Indian world. As an Anglophone movie about an Indian leader targeting a western Anglo-American audience, such a racial structuring made commercial sense. And it paid off: not only did Gandhi become one of the biggest grossing films of all time, it swept the Oscars and renewed Gandhi’s status as Mahatma for younger generations and across a larger section of the world than ever before. This similarity of narrative structures raises the question: who is the target audience for Guha’s book? One could argue it seeks to solidify Gandhi as Mahatma within a liberal, white public sphere internationally and an Indian middle class of largely upper-caste provenance distributed between the nation and its diaspora. The locus of enunciation is not so much a scholarly one as it is journalistic, and the audience is only tangentially academia.

Secondly, Guha’s biography, despite its humongous bulk, is rarely intellectually taxing as it’s not about ideas as much as it is about personalities. The reading is fast as the work moves chronologically and descriptively, framed as encounters between Gandhi and various allies, antagonists, and ashramites. These are related in a chatty style that elevates personality over principle and does not delve into the complexity of issues that divided Gandhi from many around him. Not unlike the movie, Jinnah comes across as vain, ambitious and obstreperous rather than someone with a different vantage on nationalism from Gandhi or the Congress. Ambedkar is shown as a prickly personality who resented Gandhi’s popularity and was unwilling to kowtow to his leadership, as distinct from someone whose understanding of caste and democracy was of a different order—not degree—from most nationalists. This reduction of substantive differences on caste, race, class, nationalism, gender, history, religion, and civilization to the domain of personality is accompanied by a strategy wherein Guha himself rarely disparages Jinnah or Ambedkar. Rather, he does so by citing a seemingly unbiased or neutral voice from the archive ventriloquizing that view.

And thirdly, the biography’s overwhelming reliance on sources contemporary to the years it covers (1914-48), and especially Gandhi’s own self-exculpatory renditions of events, gives it a strangely freeze-dried flavor. It allows Guha to not engage with rich veins of scholarship in fields such as history, political science, and biography that analyze Gandhi and his contemporaries through renewed eyes and a wider range of sources. Guha’s defense of his approach (mentioned in the context of a discussion of whether separate electorates for Muslims, granted as early as 1909, laid the ground for the later Partition of the subcontinent) is: “I have my own answers to these (admittedly) important questions, but this is not the place to offer them. The biographer’s task is to document what happened at the time, not to pose counterfactuals” (page 811).

This reduction of the “biographer’s task” to a sort of Rankean historical reportage (“what happened at the time”) is a choice that Guha makes, not something intrinsic to the genre of biography itself, and there is a political import to this choice. As we see below, well substantiated historical documentation regarding key events in Gandhi’s life that run contrary to his recollections or Guha’s deific narrative cannot be ignored or brushed under the carpet through a professed disinclination for “posing counterfactuals.” This scholarship requires a serious reappraisal of Mohandas Gandhi, to make a more balanced and informed judgement about the man and his actions then and their implications now—and that is surely part of the brief for any biographer? Guha’s refusal to triangulate Gandhi’s own recollections and memoirs and the sources contemporaneous to his times with more recent scholarship renders his biography intellectually thin: it reduces Gandhi’s encounters with his political, moral, and ethical adversaries and issues to matters of personality (jealousy, rivalry, prickliness, etc.) rather than engaging them in terms of their historical and political substance.

In this review, I focus on two themes. One, Guha’s depiction of the formative influence of South Africa on Gandhi’s politics and ethics. And, two, the differences between Gandhi and Ambedkar on caste, Dalits, and the nation. Focusing on these two themes—race and caste—allows us to see how works like Guha’s are central to the reproduction of Gandhi as Mahatma but obscure our understanding of Gandhi the man.

Whitewashing South Africa

At various points in his book, Guha repeats claims that can no longer be sustained, viz., that Gandhi’s South African years (1893 to 1914) were spent fighting for the rights of “Indians” in that country, that the South African prelude ended with Gandhi perfecting his technique of non-violent “satyagraha,” and that he left that country on a high note having led a successful strike by miners and plantation workers in late 1913 and early 1914 culminating in an agreement that secured their victory. Works by, among others, Maureen Swan, Kathryn Tidrick, Joseph Lelyveld, and especially two recent books by South African scholars, Ashwin Desai and Goolam Vahed, most of which Guha inexplicably ignores or deals with perfunctorily, paint a very different picture of Gandhi in South Africa.

The following sentences are typical of Guha on Gandhi’s politics in South Africa:

“He had been the unquestioned leader of the small Indian community…” (page 3);

“he moved from lawyering to activism, leading campaigns … against racial laws that bore down heavily on Indians” (page 4);

“… he had fought for the rights of plantation workers” (page 43);

“In South Africa, Gandhi’s first struggles against racial discrimination…” (page 93);

“In November 1913, he had led a slow, peaceful and yet spectacular march of several thousand Indians in Natal, who defied racial laws by crossing provincial boundaries into the Transvaal and courting arrest. By marching and sleeping in the open, and cooking their own food, and thus voluntarily inflicting suffering on themselves, the satyagrahis could draw attention to, and garner support for, their cause” (page 207);

“From 1893 to 1914, he had fought steadily for greater rights for Indians in South Africa” (page 628, all emphases mine).

Gandhi went to South Africa as a lawyer representing a Muslim merchant, and his main qualification was his fluency in both English and Gujarati as well as his training in English law. (Gandhi would describe his years in South Africa as a “self-imposed exile” (page 516). He had tried and failed to launch a career as a lawyer in India after his return from England and went to South Africa for economic reasons. Endowing that decision to seek employment abroad with the halo of “exile”—even with the qualifier “self-imposed”—also seems disingenuous.) The category “Indian” as used by Guha in many of the quotes above is misleading. Gandhi represented the small mercantile and professional community of Indians in South Africa: they were the only “Indians” he was concerned with for nearly all his time in that country. He made it clear in all his petitioning to South African authorities that he held no brief for the vast majority of Indians in South Africa: indentured laborers who worked in the plantations and mines, or those who had recently come out of their servitude but chose to stay on in that country and were part of a growing underclass there.

Gandhi’s views about indentured laborers were identical to caste Indian views of Dalits back home that, similarly, blamed the victim. The only group even further down the ladder of inferiority in Gandhi’s view was native Africans whom he referred to as “kaffirs” throughout his time in South Africa. Gandhi’s views about these ex- and indentured Indians were indistinguishable from the worst racial stereotypes entertained about them by whites: he considered them dirty, untrustworthy, infantile, and prone to drunkenness, adultery, crime, and sloth. He regarded their benighted condition as moral failings and, owing to sins committed in past lives, as distinct from their being virtually slaves in a settler colony. His views about indentured laborers in other words were identical to caste Indian views of Dalits back home that, similarly, blamed the victim. The only group even further down the ladder of inferiority in Gandhi’s view was native Africans whom he referred to as “kaffirs” throughout his time in South Africa.

Gandhi interacted mainly—almost exclusively—with a small group of white friends and colleagues in South Africa. They shared his view about coolie Indians and kaffir Africans, and that Indians like himself were racially and civilizationally far closer to whites than they were to either of those two. Guha devotes a fair amount of space to Gandhi’s interactions with these individuals even after he returned to India (Kallenbach, Polak, and others) but makes little mention of their racial ordering of the world. While Guha acknowledges that Gandhi’s interactions with black South Africans was non-existent, he never makes explicit that the situation was not very different when it came to his interactions with the ex- and indentured laborers. Rather, the loosely used category “Indian” papers over class and caste distinctions that were very important to Gandhi at this time, and gives the erroneous impression that he fought against the white settler regime for the rights and prospects of all Indians there as distinct from the tiny class fraction he mostly represented.

Gandhi twice served as head of a volunteer “Indian” stretcher corps that he himself proposed and mobilized: on the first occasion on the side of the British against the Afrikaners in the Boer War (1899-1902), and the second in 1913 on the side of the white Anglo-Boer regime against Zulus when the latter rebelled against the Union of South Africa, which had forced their alienation from their own lands. On both occasions, Gandhi sought favours for his constituency of upper class and caste Indians by proving his loyalty to white empire—literally over black bodies. On both occasions, as well, the stretcher corps was seen by him as a consolation prize—he would much rather have served as an armed combatant to prove the worthiness (manliness) of Indians like him, and their parity with the colonizer in killing native Africans. The centrality of violence as a means to human being, and its role in the racial hierarchy in Gandhi’s thinking at this time, was no aberration. When he stopped in England in 1914 on his way back to India and as the Great War looked imminent, he threw himself into efforts to mobilize volunteers for that conflict to the amazement of many who had taken his many pronouncements on non-violence at his word. Violence as a cleansing and annealing force in attaining manhood or nationhood resurfaces repeatedly in his writings thereafter, recurs in his praise for Adolf Hitler as late as 1939, and informs his ardent desire to die a violent death at the hands of an assassin rather than of illness or old age.

Many years ago, Ashis Nandy had commented astutely on the centrality of violence to Gandhi’s ethics and politics (see his essay “Final Encounter: the politics of Gandhi’s assassination” in his At the Edge of Psychology: essays in politics and culture).[efn_note] Delhi: Oxford University Press, 1980: 73-87. [/efn_note] This centrality has been further explored by Faisal Devji in his recent The Impossible Indian: Gandhi and the Temptation of Violence.[efn_note] Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press, 2012. [/efn_note] What these works, alongside others mentioned in note 4, would seem to necessitate is a reappraisal of the ethics of Gandhian non-violence. While considerations of space preempt a fuller analysis here, at minimum it appears that (a) Gandhi was quite enamored of peoples, races, castes and nations that had the capacity and the will to inflict violence on others; (b) that he never quite outgrew his admiration for violence as an index of strength and masculinity even into his final years; and (c) non-violence was a moral, cleansing and ethical force only when exercised by the strong, that is, upper castes and superior races, and not when exercised by those in positions of inferiority or weakness.

This imbrication of the morality of violence with the hierarchies of caste (and race) is something that Ambedkar alluded to in his many engagements with Gandhi, and is something that awaits fuller historical and intellectual investigation. I merely note it here at this moment.

Violence as a cleansing and annealing force in attaining manhood or nationhood resurfaces repeatedly in his writings thereafter, recurs in his praise for Adolf Hitler as late as 1939, and informs his ardent desire to die a violent death at the hands of an assassin rather than of illness or old age. Later, in his memoir on his South African years, Gandhi would make much of the impact the slaughter of the Zulus had upon his conscience—something Lelyveld (2011: 71) bluntly describes as a “retrospective tidying up” but which Guha sees as proof of Gandhi’s overcoming his racism. Yet, in South Africa, he constantly and obsequiously entreated the regime for equal opportunity for Indians like him to join combat against the outgunned Zulus. The casualties from the “war” to suppress them were so lopsided that even a sanguinary imperialist and white supremacist like Winston Churchill, at that time a young reporter, filed back to London objecting to the indiscriminate slaughter. Gandhi repeatedly admired the bloodlust of English soldiers, something he saw as explaining, even justifying, their rule over much of the world including India. Incredibly, at this time Gandhi was preaching non-violent resistance to the soon-to-be-killed Zulu chief Bhambatha and his followers in his newspaper columns while simultaneously pleading with the white regime to allow Indians like himself to ditch the stretchers and take up arms against the Zulu.

The depth and mendacity of Gandhi’s racism, his casteist and patronizing attitude towards the ex- and indentured Indians, and his unceasing effort to ingratiate himself with whites as a civilizational equal, are all muted in Guha’s biography. Instead, South Africa is inscribed as a prolepsis for Gandhi’s struggle against colonialism and caste inequality after his return to homeland.

A large part of the case for regarding South Africa as the crucible for Gandhi’s technique of non-violent resistance or satyagraha comes down to his final year there. In late 1913, the country was rocked by one of the most militant and sweeping movements for economic justice by indentured laborers who went on a strike that paralyzed the country. The strike spread from the plantations and mines to include both black and white working classes and across a variety of other sectors of the economy. This was the only struggle in his 21 years in South Africa in which Gandhi allied himself with the laboring classes of Indians in that country, and its allegedly successful resolution enabled him to return to India as a leader of consequence.

Gandhi sought favours for his constituency of upper class and caste Indians by proving his loyalty to white empire—literally over black bodies. It’s worth noting that a few months prior to this strike in late 1913, the mercantile class that had constituted his core constituency in South Africa had a falling out with Gandhi over his vacillating leadership and propensity to package craven compromises as tactical victories in his parleys with the regime. In other words, Gandhi’s brief flirtation with the class politics of indentured labor came only after having burned his bridges with the ‘better’ class of Indians he had proudly represented until then. Even so, Gandhi made it clear that the striking laborers should not make common cause with the Africans, many of whom were on strike as well. By this time, he was mentally packing his bags for India as his South African sojourn seemed to be reaching a political and economic dead end for him. This would also be the moment when Gandhi’s politics would take on a more explicitly Hindu coloration, something held in check so long as his paymasters were Muslim merchants.

Gandhi’s final months in South Africa were not quite the militant crescendo followed by triumphant farewell that Guha portrays. Firstly, there is ample evidence that far from leading this struggle, Gandhi was caught by surprise at the rapidity with which the strikes spread through the plantations and mines, as well as the extent of their violent militancy. As Desai and Vahed note in their book: “Clearly Gandhi did not envisage the scale of involvement of the miners. It was, after all, not a constituency he had worked with or on behalf. He told the Rand Daily Mail on October 23, 1913, that he had ‘never expected that the response would be so spontaneous, sudden and large.” [efn_note] Desai and Vahed, 2015: 150. [/efn_note] Gandhi repeatedly exhorted laborers to moderation, to respect the property of plantation and mine owners, and to refrain from violence even in face of the most extreme provocation by police or the armed foremen. The solicitude Gandhi shows for the property of mine and plantation owners in an economy built on African and Indian slave labor is really quite remarkable, and it’s a solicitousness that would mark his politics to the very end of his life.

Secondly, Guha makes much of the fact that the miners slept out in the open and established community kitchens to feed themselves, and argues this was a part of their training as satyagrahis inspired by Gandhi. Yet, as Desai and Vahed note, indentured laborers in South Africa had a long history of resistance, both in its everyday forms and with occasional irruptions into violence and strikes against what was slavery by another name. This tradition of resistance predated Gandhi’s arrival in their midst and would endure long after he had left. There is not much evidence that they saw themselves as satyagrahis pursuing his plans, besides Gandhi’s own self-aggrandizing claims in this regard and now cemented into history by repetition in various hagiographies.

In a passage emblematic of the distance that separated Gandhi’s politics from their militancy, Desai and Vahed note:

“Most accounts of the strike reinforce the Gandhi-centric story by focusing on the ‘epic’ march across the border of Natal and the Transvaal. But the strikes spread across caste, class and gender lines; engulfed large parts of the province; and was often outside the control of Gandhi and his coterie of leaders … The methods of strikers in coastal areas were frequently far removed from the notion of passive resistance, the dominant discourse in which the strike is narrated. Whatever Gandhi’s original intentions, phases of the strike were anything but passive. This part of the story has not been given sufficient prominence in the historiography. This may partly be a result of basing the narrative around Gandhi, which is understandable given the reliance on his autobiographical writings and the works of his associates. The focus on Gandhi may also have been prompted by his subsequent role in the anti-colonial struggle in India, or the power of satyagraha (passive resistance) as a moral force in ‘our times.’ As our narrative reveals, strikers were not necessarily imbued with the spirit of satyagraha. This is not to discount the massive influence of Gandhi, but rather to write back into history the fertile texture of the historical experience of the indentured, who dug deep into memories of past collective and individual resistances and ‘invisible’ networks to mount a serious challenge to authority and, for a short while, caused panic in the ranks of employers. The strike spread to the coastal areas in spite of, not because of, Gandhi who wanted to contain it. … There were experiments with armed struggle. Sticks and knife caches were hidden along roads, cane fields were torched, policemen ambushed, white farmers besieged and taken hostage. So threatening did these attacks become that reinforcements were sent from as far afield as the Eastern Cape. While organization and coordination was poor, and repression brutal, the passive resistance campaign was, in large swathes of the former Natal, an uprising, and a fairly militant one at that” (Desai and Vahed, 2010, page 399).

Amidst this militancy, Gandhi’s concerns were, as would be typical of him till his dying day, about the inviolable rights of the propertied. As Desai and Vahed note in their more recent (2015) book:

“Gandhi stated that strikers were urged to leave the mines because it was ‘improper to live on mine rations when we don’t work’. This must have sounded hollow to mine workers. Their owners oversaw a brutal labour regime enforced by white foremen who often acted as gangsters. Miners had risked everything in taking on their employers, yet Gandhi was preaching in moralistic tones about taking rations from owners who had taken their very blood” (page 154).

Gandhi wrote of this movement at the height of its militancy that “they struck not as indentured laborers but as servants of India. They were taking part in a religious war.” In his recollection, many of the common slogans raised during the protests were in the vein of “Victory to Ramachandra,” “Victory to Dwarakanath,” and “Vande Mataram.” It is noteworthy that after having spent two decades denying the Indian-ness of these laborers, Gandhi now elevated their national identity over class. Further, freed of his Muslim sponsors, he misrecognizes them as participating in a “religious war.”

Gandhi’s equation of these “servants of India” with Hindu “religious warriors” and his explicit disavowal of any notion of class identity in their politics add up to a vexing brew. It indexed an understanding of the Indian nation as one inextricable from a Hindu ethos, and a distaste for political action motivated by resistance to economic or class exploitation. His politics revealed a highly top-down and pedagogical approach to leadership even as those he claimed to represent frequently outflanked him. As Lelyveld (2011: 128) notes in regard to his equation with the Indian underclass in South Africa: “he could speak of them and for them, but mostly, he wasn’t speaking to them.”