The Imaginary Institution of India re-narrates the nation through art from 1975-1998.

The verb “imagining”, to me, is one of the most significant in the human vocabulary. It comes from the Latin imaginari, meaning “to form a mental picture” or “to picture to oneself,” with the Proto-Indo-European root aim- or aimo- relating to copying, imitation, or representation. Imagination enables us to build ourselves off the past—our dreams, systems, relationships—so it’s what drives and catalyzes any political force.

In 1983, political scientist Benedict Anderson famously coined the term “imagined communities” to describe the concept of nations. He called the bluff, arguing that a nation is inherently imagined or made up, a group of men drawing up lines on a table. I could never possibly meet every member of my country, yet those lines and my place within them, dictated by a document, could bind us in solidarity, patriotism, or nostalgia. Dulce et decorum est pro patria mori (It is sweet and fitting to die for one’s country)—all for a social construct.

This year at London’s Barbican Centre, an exhibition titled The Imaginary Institution of India: Art 1975-1998 (5 October 2024 – 5 January 2025) unfurls those years in which Anderson was ideating and my mother was discovering Michael Jackson, migrating out of India to southern Africa, and having me—years that exist, to me, just in my imagination. The exhibition’s title comes from a 1991 book by Sudipta Kaviraj of the same name, which discusses the formation of India as a political entity—or imagined community—and how the nation evolved post-colonization.

Four themes mold the show: “the rise of communal violence, gender and sexuality, urbanization and shifting class structures, and a growing connection with Indigenism.” The mediums are varied, from traditional oil on canvas to giclée prints, video, multimedia installations, textiles, wood, pigments, cow dung, pastel, indigo, and more. Such a lush range of materiality offers a visceral connection with the actual, variegated land of India, albeit from afar. And it gives a shape, a concreteness, to the differing emotional paths the artworks lead viewers down.

Works by 30 Indian artists explore over two decades of instability, tearing, and suturing in the country—a period with immense resonance for India today under Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). The 1970s-90s saw independent India’s first brush with authoritarianism; similar suppression of dissent, targeting of dissidents, and a more concentrated centralization of power occur now. The BJP’s focal ideology of Hindu nationalism also saw its beginnings pre-millennium, its flashpoint being the Ram Janmabhoomi movement and the consequent demolition of the Babri Masjid in 1992.

It might be difficult to imagine the exhibition’s diverse lineup being allowed to be feted within India now. Jangarh Singh Shyam, Sheba Chhachhi, Tyeb Mehta, Gulammohammed Sheikh, Arpita Singh, Vivan Sundaram, Meera Mukherjee, Jitish Kallat, and more. There are established names, internationally undersung pioneers, and names that could have been buried, revivified here. For all their plurality, as well as many of their radical, leftist, and Marxist politics, these artists often appear in near-complete opposition to the BJP’s aggressive right-wing approaches, which, as we discover, many of these artists have felt in the past.

This may explain why the exhibition is not currently traveling to India. One of the nation’s premier contemporary art institutions, New Delhi-based Kiran Nadar Museum of Art, has offered generous support through loaning works and expertise as the Barbican’s collaborators but is not slated to host the show.

Competing Imaginations: Ambedkar, Hindutva, and the Colonial Specter

Emerging from the aftermath of brutal British colonialism and a traumatic partition in 1947, India—like most postcolonial nations—was a project in need of reimagining. The main custodian of this task, Dr. B.R. Ambedkar drafted one of the most detailed constitutions in the world, espousing democracy, secularism, inclusivity, and rule of law while eschewing divisive ways of belonging upon religion, caste, gender, or place of birth.

But if a country is an imagined community, even the strongest constitution struggles to cohere the thousand babbling interpretations of what that nation could be instead. What happens when one’s imagination conflicts with another, when people have differing notions of harmony, peace, or community? Where Ambedkar’s constitution sought to celebrate pluralism, reveling in the notion that there is no single, fixed “India” or “Indian”, others laid plans for a far more homogenous state, what scholar Sara Ahmed would call a “harder touch.”

For instance, Vinayak Damodar Savarkar’s 1923 pamphlet Essentials of Hindutva “called for Hindus, hopelessly divided by caste, to come together…and reclaim their ancient homeland from… outsiders, primarily the Muslims.” Savarkar’s views became central to the formation of the BJP’s parent organization, the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), which positions him as a “nationalist icon.”

The Imaginary Institution of India is bookended by two major historical events—the 1975 Emergency declared by then-Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, which temporarily suspended democracy through autocratic rule, and the 1998 Pokhran nuclear tests, which effectively made India a nuclear power. Economic and social upheaval abounded in both private and public spheres. High communal tensions, rising unemployment, and etched patriarchal, religious, and casteist divisions flared.

This period of Indian history has never been explored before, and so thoroughly, in a major arts institution. Most often, instead of spotlighting modern and contemporary artists responding to how India has shaped itself post-independence, UK institutions huddle in the perceived neutral safety of objects, ruins, and histories so old and distant they nearly defy imagination. This results in gorgeous yet faintly Orientalised and politically antiseptic shows, like the recent The Great Mughals: Art, Architecture and Opulence at the Victoria and Albert Museum, sumptuous as it is.

During my visit, I was instantly awed by the exquisite remnants displayed from the reigns of three Mughal emperors—Akbar, Jahangir, and Shah Jahan. About thirty minutes in, however, I noticed the awe of other people around me and simultaneously, the distance of feeling between us.

Every work on display was owned and kept outside the Indian subcontinent, in collections spanning the UK, North America, and the Gulf. I was staring at pieces of history that felt like they should have belonged to me too, to my imagined community. Yet, even in their presence, I felt a complicated sense of alienation and loss—a glass vitrine and an imperialist nation stood between us. It’s a cognitive discord filmmaker Mati Diop explores in this year’s magical documentary Dahomey, questioning the role of art and objects in nation formation and continuity.

The Imaginary Institution of India’s curator Shanay Jhaveri is “the first non-white and non-British person to serve as the Barbican’s Head of Visual Arts” since its establishment in 1982. For this show, he has worked alongside research associate Qamoos Bukhari, who is Kashmiri Muslim, and curatorial assistant Amber Li. Jhaveri’s appointment serves as a model not only for aspiring and early-career South Asian cultural practitioners but also for visually narrating a nation with both rigor and intimacy.

As Jhaveri states in a recent video, “This exhibition has been long overdue.”

Labor, Love, and India’s Workers

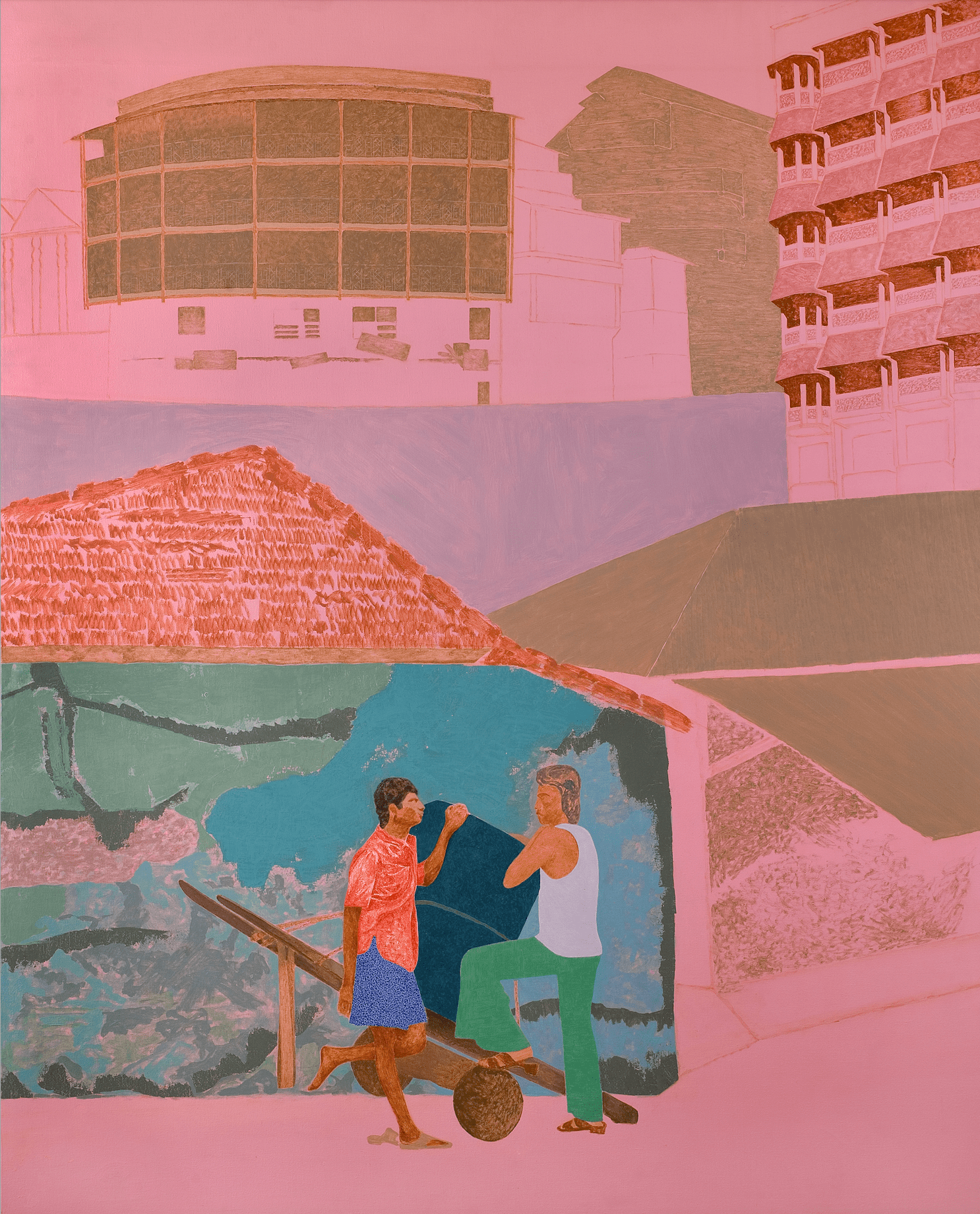

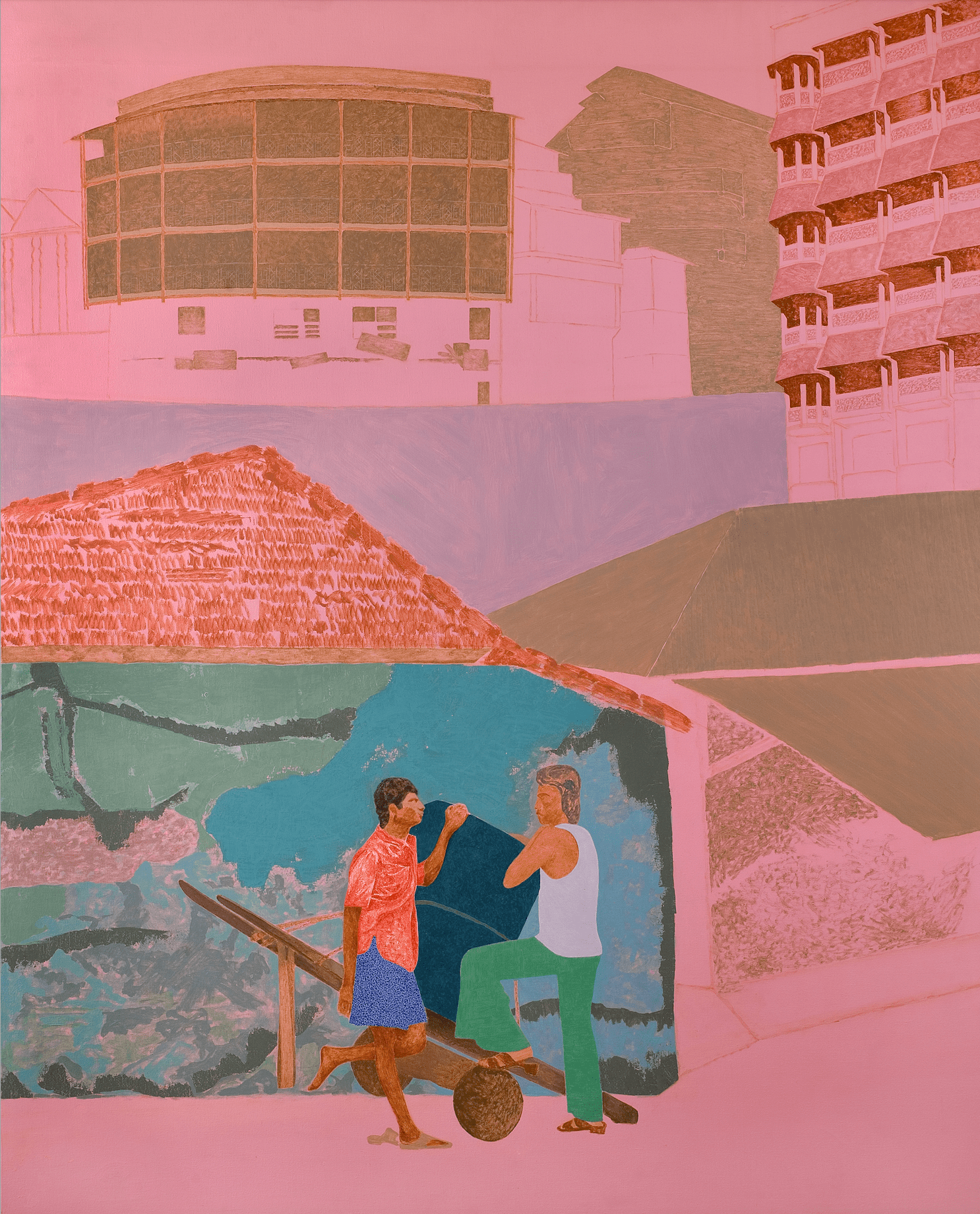

In The Imaginary Institution of India, there is no wall text. Small stacks of hot pink catalog booklets, the comfortable size of slim paperbacks, lie in wait at the entrance. Beside them is the opening artwork, Gieve Patel’s Two Men with Hand Cart (1979), donned by all the exhibition posters. It depicts two male laborers breaking to chat against a pink sky, with Bombay’s buildings burgeoning behind them. We presume they are part of the construction, this overwhelming execution of the imagination. An immediate tone is set: the show’s prevalent focus on workers’ lives, and those forgotten yet foundational to a country. A simultaneous sense of softness and pain is evoked by the pink—the color of a sunset’s aftermath.

Gieve Patel was primarily a physician, similar to Sudhir Patwardhan, a radiologist painter. The medical profession required enormous intimacy with the city’s poorest and sickest, resulting in constant close contact with the realities of the widening class divide and the healthcare system’s flaws. Alongside paintings by Patel and Patwardhan, Navjot Altaf’s Factory series (1982) addressing the 1982-83 textile strikes, and Nalini Malani’s video gaze on city slums, The Imaginary Institution of India often props Bombay as a microcosm of the country itself. The city-as-state’s workers, many of whom have migrated in thousands from rural homes, are foregrounded for viewers to experience the subjectivity of their daily lives, which are shaped but not solely defined by the value of their labor.

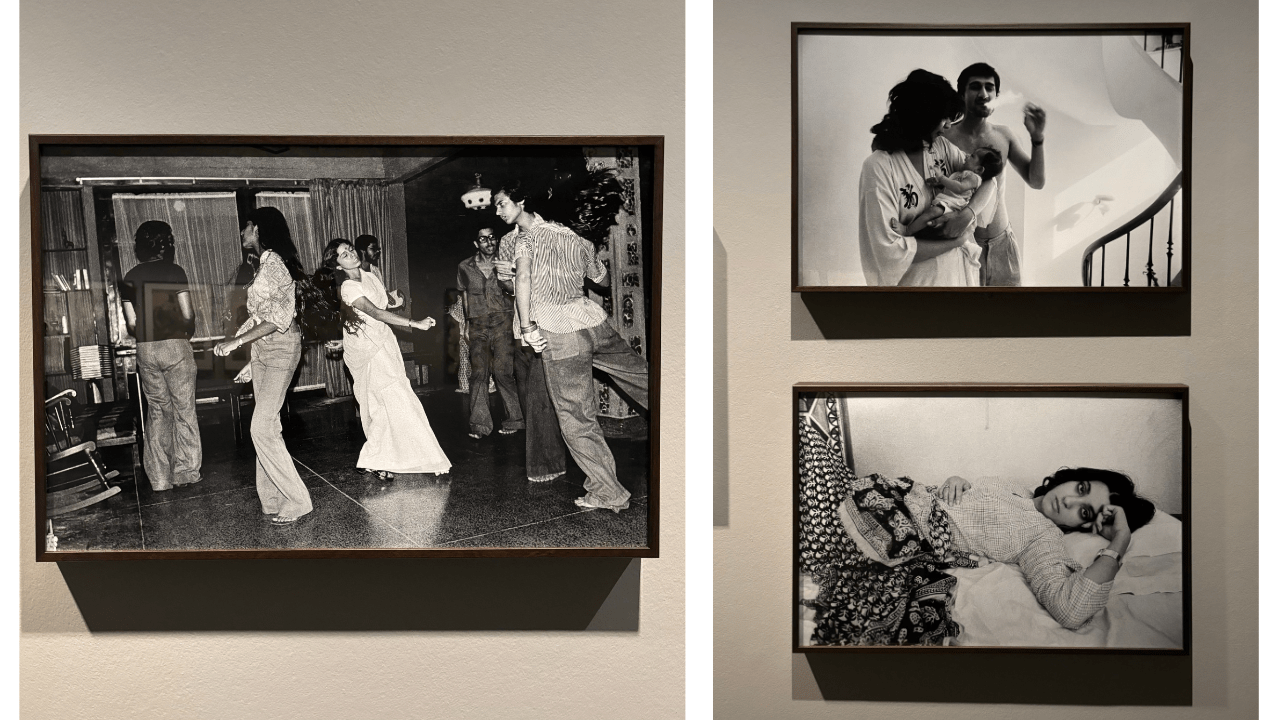

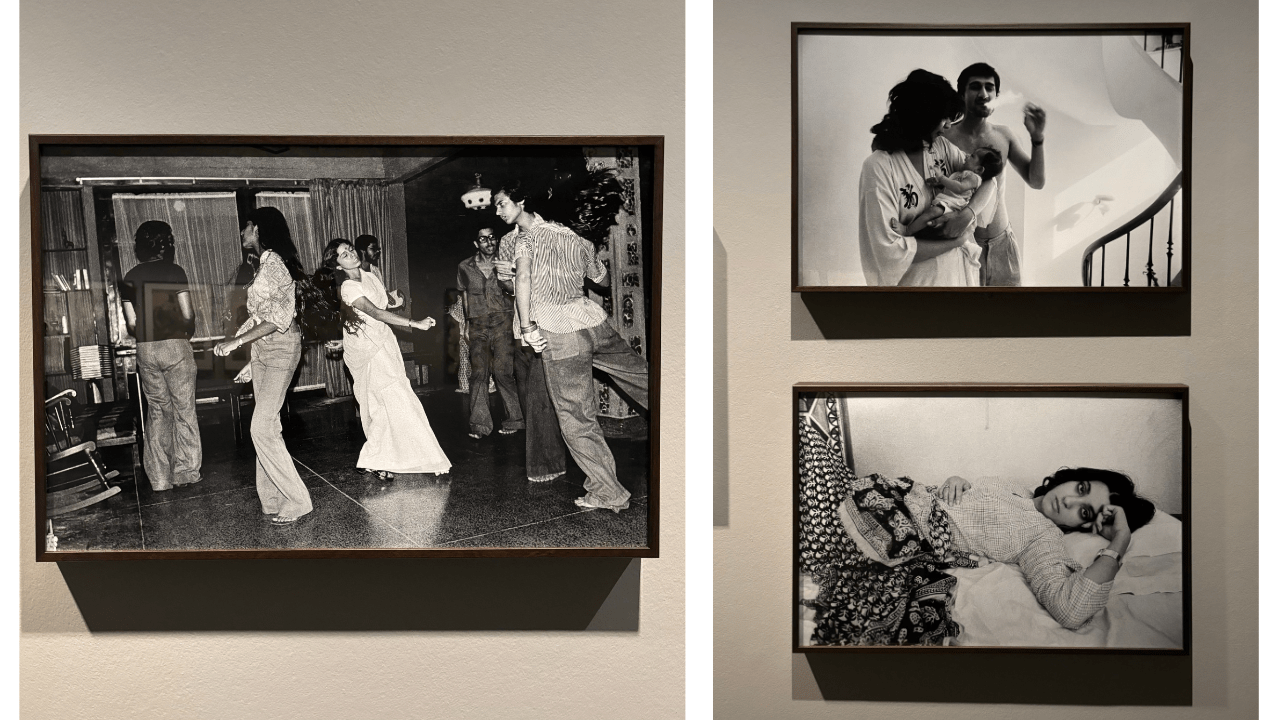

Although we see the various, grueling ways in which the country flushes its workers through its systems—like a heart does blood—these artworks also illuminate their subjects’ leisures, pleasures, and routines built around and off their work. For instance, photojournalist Pablo Bartholomew’s images of young people in Bombay and Delhi at the height of the Emergency portray the bits of life’s glitter youth especially seized within private spaces. They lounge, laugh, dance, smoke in bed, have debates, indulge in friendships, parties, and romance, following their desires away from a tense, repressive public environment that wants to constrain them.

Such themes form the nearly identical premise of this year’s Cannes Grand Prix-winning film All We Imagine As Light, directed by Malani’s daughter, Payal Kapadia. The multilingual film follows two female nurses and a cook, long-term migrants working in the same Mumbai hospital. Warm jazz and monsoon blues bathe these women as they live within their world’s hierarchies—urban gentrification, patriarchy, language, religion, and social taboos—while trying to experience love and pleasure in all forms. The movie is breathlessly beautiful, yet quietly scathing about the obstacles inhibiting free love among Indians across social strata, much like Arundhati Roy’s 1997 novel The God of Small Things.

An effective state might try to alleviate these divides. Yet over the years, India has seen the governance of different moneyed, hate-mongering thumbs; there is subtle continuity from The Imaginary Institution of India’s focal history to the present. The care with which it curatorially unfolds is nothing short of a rich screenplay like Kapadia’s or other unconventional filmmakers, many of whom are included in an accompanying film programme. This way, the exhibition also makes ideal use of the Barbican’s cinema model.

Indian Parallel Cinema in Dialogue with the Exhibition Space

The film programme chronicles the rise of Indian Parallel Cinema, one of South Asia’s first postcolonial film movements, which “gave agency to themes, narratives and groups … rendered invisible or marginalized on screen.” Among the included films are Amma Ariyan (dir. John Abraham, 1986), situated amid leftist political activity in Kerala; Deewaar (dir. Yash Chopra, 1975), which established the Angry Young Man trope popularized by Amitabh Bachchan, symbolizing a generation’s “collective angst…with socio-economic inequities”; and Ram Ke Naam (dir. Anand Patwardan, 1992), a documentary still restricted in India for exploring the Babri Masjid’s razing by a right-wing mob.

These films extend the conversations begun in the exhibition space. Further supplementing the well-researched, eloquently written catalog is a patient yet exhaustive audio guide that can be accessed from one’s phone. The experience of the exhibition becomes less of a tiring day at the museum then, to something more immersive, like submerging oneself within one of these films.

The Angry Young Man trope builds upon searing works by Patel, Patwardhan, Malini, and Altaf, among others. For instance, Altaf is also showing her 1976 Emergency Poster series, “inspired by the visual language of Cuban political propaganda” and meant to be used for activist demonstrations “against government corruption.” Free speech and dissidence—the existence of which measures a democracy’s health—are currently under heavy crackdown. Yet Altaf’s posters remind us that protest culture has existed, flourished, and evolved from its own distinct past in India.

Meanwhile, the themes of Ram Ke Naam expand a dialogue on communal politics fueled especially poignantly by M.F. Husain, one of India’s most renowned modern artists. He was forced into exile in 2006 largely due to threats from a Hindu nationalist group, the Vishwa Hindu Prasad, and the BJP.

Husain’s 1986 painting Safdar Hashmi depicts the killing of the titular political activist, actor, and playwright while performing a street play outside Delhi. Hashmi was a major theatre figure, founding the Jana Natya Manch, or “people’s theatre forum”, which “staged plays in public spaces and working-class neighborhoods to counter attempts by the ruling class to suppress dissent.”

Husain depicts Hashmi’s death with deep dignity and emotion while emphasizing its brutality—Hashmi’s limbs are broken severely, rigid scarlet lines ramming through the image. He is shown as less of a person than a vehicle of ideas so forceful and fearless it had to be shattered and taken apart.

I stood for a long while in front of this painting, my chest thick and full as if welling with water. The image before me did not feel new, yet Husain made it feel so. Today, social media and other digital platforms flood with visuals of public assaults and lynchings of Muslims for the tiniest “transgressions,” like possessing beef or simply walking down the street in parts of India. That they proliferate so much hardly radicalizes but inures us against their impact. The more ubiquitous the images, the quicker their force drains out of our collective vision.

But many of these artworks in The Imaginary Institution of India restore the viscerality of the pain, so cushioned by our algorithms, that we have long inflicted on each other. Artist Rummana Hussain, who had to flee her Bombay home amid riots following the Babri Masjid demolition, displays her 1993 series of broken terracotta pots, littered with gheru (powdered red clay) and rubble spilling on fragmented mirrors. The result is trauma as a kaleidoscope: the viewer sees shattered domes, bodies, land, and earth refracted together.

Towards Equality: Womanhood and Queerness

Where there was an Angry Young Man, there were many, many Angry Young Women. In 1974, a government report titled Towards Equality stated that women were “far from enjoying the rights…guaranteed to them by the constitution,” sparking a wave of nationwide women’s movements. Various female artists, each with their own feminist thinking and positionality within the country’s social landscape, created works in response. Some are more documentarian and radical, while others turn inward to desires, fantasies, and imaginings.

Part of these movements was Sheba Chhachhi, whose stunning black-and-white photographs Seven Lives and a Dream (1980-91) follow seven women activists protesting anti-dowry violence. What’s striking about the series is that—in addition to these intensely emotional images—Chhachhi returns to her subjects a decade later, letting themselves choose how they want to be photographed in the aftermath of who they once were. Some occupied the private sphere, surrounded by personal items like typewriters. Others retained being seen in the public arena. One activist named Sathyarani sat on the steps of the Indian Supreme Court; from here, she had spent decades fighting for justice for her murdered daughter.

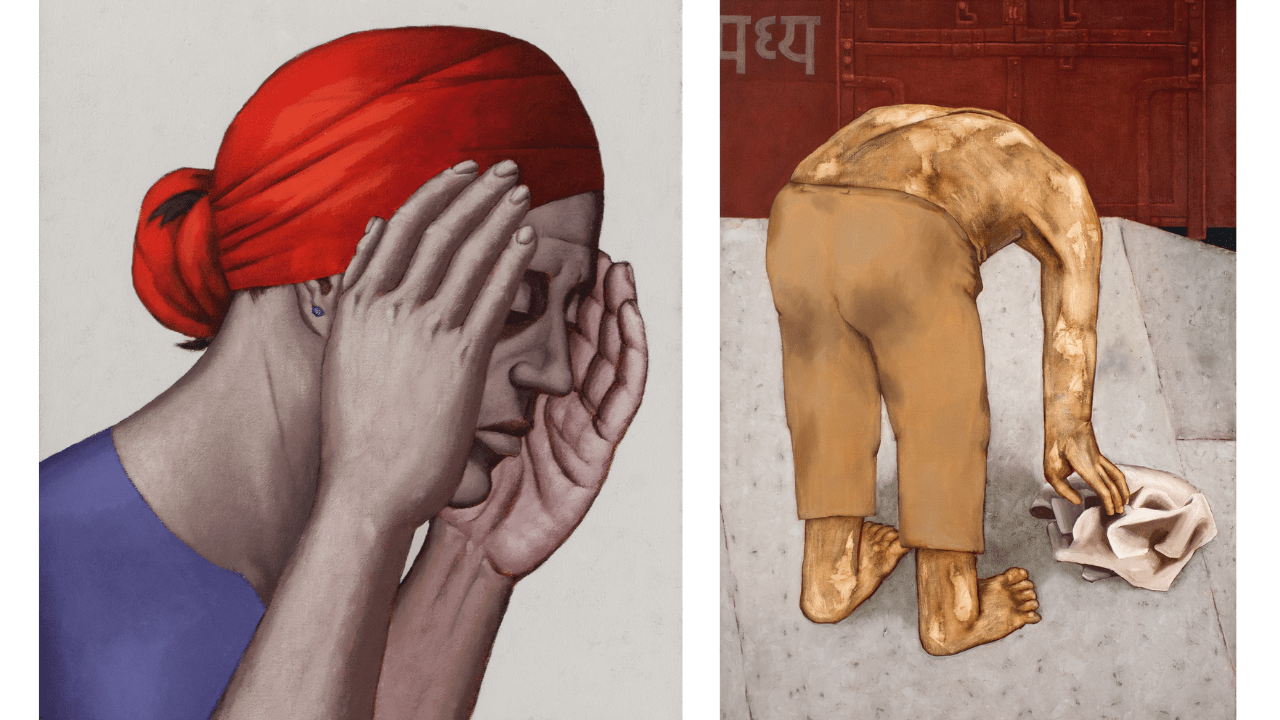

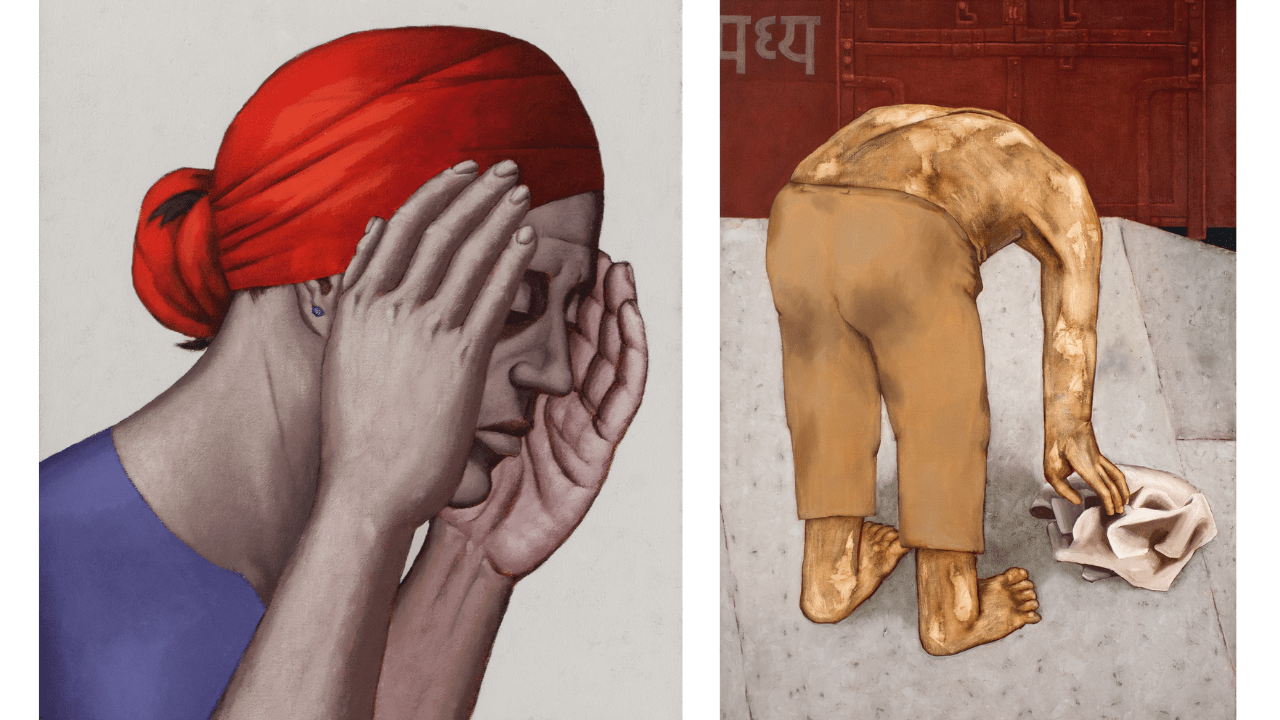

Prominent artist Nilima Sheikh presents some standout works from The Imaginary Institution of India. Her series of 12 narrative paintings, made with tempera on Sanganeri paper, chronicles the life of a teenage girl named Champa, titled When Champa Grew Up (1984-5). The images are childlike and naive, yet their content is progressively harrowing. Sheikh personally knew the girl in the story, who was married as a child into an abusive family and eventually murdered by them for dowry-related issues.

The tale is disturbingly similar to one of the plots in Anita Desai’s 1999 novel Fasting, Feasting, in which a young Indian girl has to forgo an Oxford scholarship for marriage. Her husband treats her as a servant when she cannot bear children, and it is heavily implied that he and his family then burn her to death.

But the exhibition’s representation of Indian women is not just limited to trauma. Another of Sheikh’s works, an enormous double-sided painted canopy, forms an installation one can walk in and around to visit different life experiences of Indian women. Shamiana (1996), named for the South Asian ceremonial tent used for festive occasions, depicts moments of pleasure, community, solitude, dance, domesticity, suffering, and more. Sheikh’s work celebrates Indian women as whole, distinct subjects, rather than flat objects upon which society projects its pitfalls.

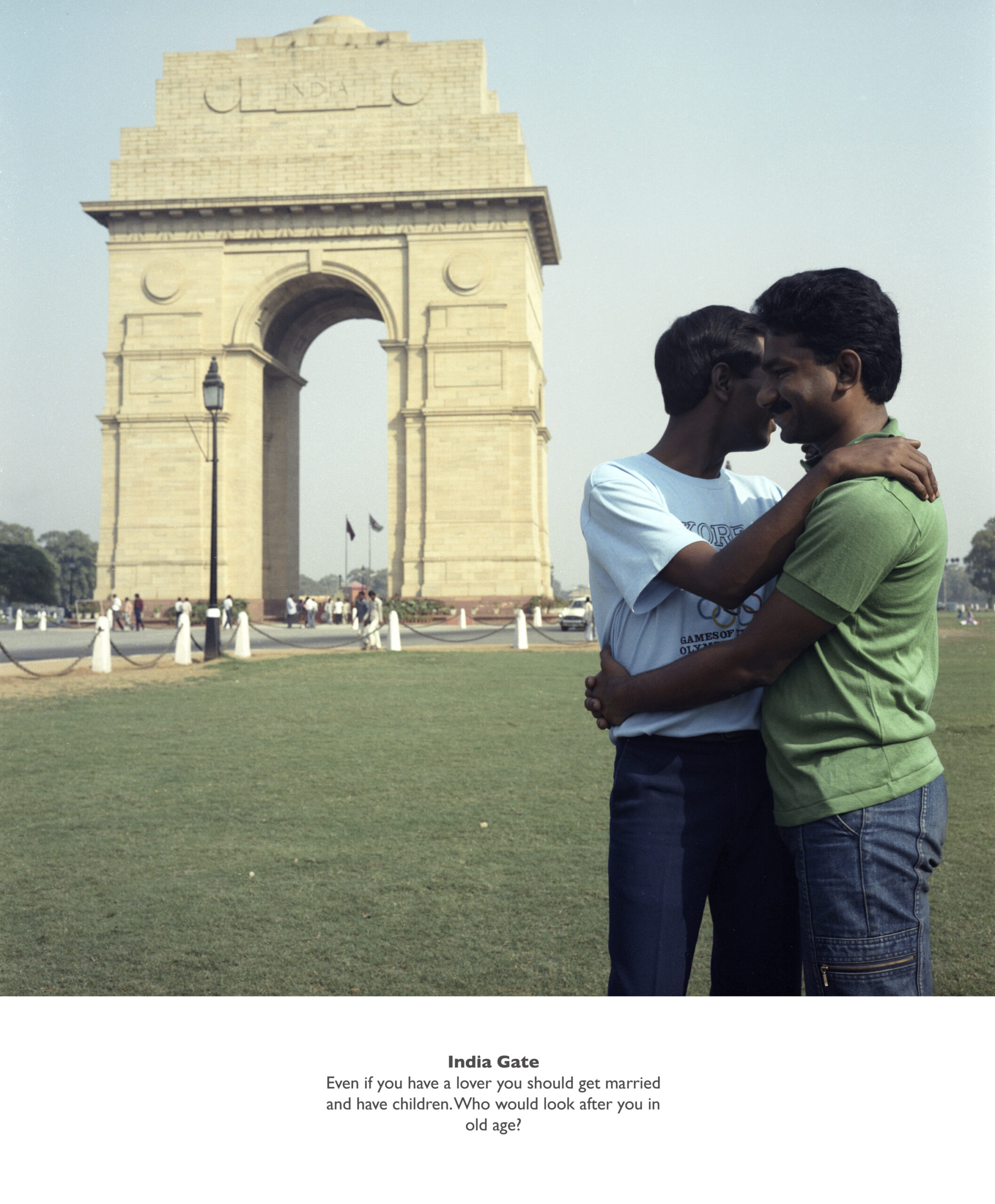

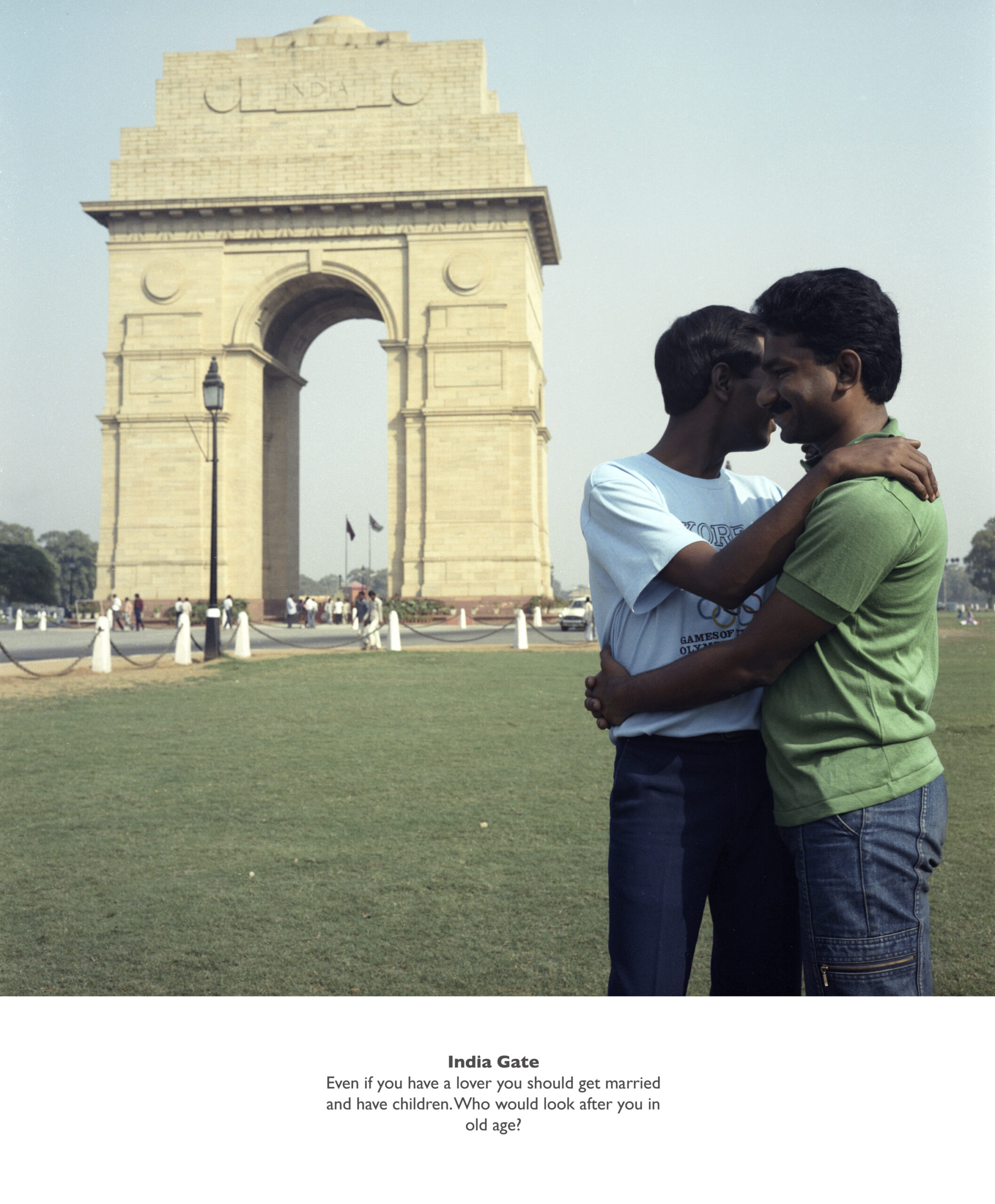

The Imaginary Institution of India approaches sexuality, too, with assertive joy and celebration above trauma. Since 1861, the colonial law Section 377 effectively criminalized homosexuality in India. It was only repealed in 2018, though queerness remains highly taboo. In Exiles (1987), photographer Sunil Gupta stages gay men at various New Delhi landmarks, with accompanying excerpts from their conversations. Some are snarky, some warm. At Nehru Park, the text reads: “Police operate here harassing people and intimidating them with beatings and extortion. Sometimes they just want a blow-job.” The series was never shown in India until 17 years later.

Similarly, queer artist Bhupen Khakhar’s work, particularly one of his finest paintings Two Men in Benares (1982), had to be stored away only two days after its unveiling at Bombay’s Gallery Chemould in 1987, fearing protests. The painting depicts two naked men entwined against a deep blue background, with smaller quotidian scenes around them. Benares, now Varanasi, is one of India’s holy cities for Hindus.

“By staging this sexual tryst within a religious context,” the catalog elegantly reads, Khakhar “knowingly props up the erotic against the sacred, and provocatively collapses the boundaries between private and public.” In Gupta’s photographs, Khakhar’s idylls, and elsewhere, there are wisps of utopia, imagining an alternative, dream world in which two men in Benares or Delhi can publicly love each other.

India’s Most Vulnerable: Caste, Indigeneity and the Environment

This yearning for a better elsewhere has only deepened with national dystopias. In 1984, one of the world’s worst chemical disasters occurred in Bhopal’s Union Carbide pesticide plant, spreading a dense, deadly gaseous fog all over the city. Thousands died within just three days and it is estimated that over 15,000 more succumbed in the following years, with countless more suffering from—and birthing children with—permanent disfigurements and disabilities. Pablo Bartholomew covered the incident and its aftermath for over 20 years. Four images from 1984, the immediate aftermath of the leak, are on show in The Imaginary Institution of India. Dead livestock abandoned on open land; a Union Carbide sign vandalized in red; a father burying his daughter.

The Bhopal tragedy presents a neat nexus of different issues that have plagued India from those decades to now, notably explored in Indra Sinha’s impeccable 2007 novel Animal’s People. The environmental disaster was attributed to human error, poor safety procedures, company negligence, and faulty equipment at an already understaffed plant. Union Carbide was a subsidiary of an American firm, which, along with the Indian government, has continually failed to take responsibility, properly clean up the site, or provide adequate compensation to victims even now. Fueling this decades-long catastrophe is the cruel, grinding engine of global capitalism, crushing all, but especially those most vulnerable.

To speak of India’s most vulnerable is to address its Adivasis, or indigenous and tribal inhabitants, and its Dalit population, among India’s most systematically marginalized. The Imaginary Institution of India dedicates decent space to Indigenous artworks, such as those by Jangarh Singh Shyam from the tribal Pardhan clan from Patangarh. Shyam depicts memories of his village life, drawing on its rituals, traditions, and myths to form a distinct visual vocabulary. This grows nostalgic as communities like his are impacted by capital-driven urbanization with many migrating to larger cities for work.

Similar themes emerge in Himmat Shah’s terracotta sculptures and Savindra Sawarker’s etchings of the daily lives of Dalit people. Sawarker became known for pioneering a Dalit and Ambedkarite artistic language, including iconography such as the matka (pot) and jhaadu (broom). Meanwhile, Shah was influenced by his birthplace of Lothal, Gujarat, one of the sites of the Indus Valley civilization. His use of clay stemmed from watching the Archaeological Survey of India excavate ancient pottery as a child and his own memories of the landscape. Through his sculpted heads, Shah “took an ancient material and brought it forward to give it a contemporary edge.”

The Master’s House: Indian Art in the UK

That such vast formal, historical, political, social, and cultural scope can be packed into a single exhibition’s portrait of a country at a particular time, is a more momentous feat than one can imagine. That it has arrived, the first of its kind, in the UK before India is unfortunate for those Indians who cannot see it in their own country, yet significant for the UK’s visual arts trajectory.

Beyond the mostly British critics who have reviewed the show favorably—albeit with distance from India itself as a political entity—what it could mean for British Indians, Indian diasporas, and visiting Indian audiences is as yet immeasurable. They have the potential to engage their country’s history as visualized by its diverse people, carrying its stories and lessons as beacons with which to navigate a fraught political present.

Indians comprise approximately three percent of the UK’s population and are its largest and most economically prosperous non-white demographic. Yet India as an educational and curatorial focus still manifests less as engaging with a complex country and more as a cabinet of curiosities for the British.

There have been some shows. A couple have focused directly on India and the UK’s colonial relationship while keeping Britain the primary locus—India in Britain: 1858–1950 and South Asian Modernists 1953–1963 at Whitworth Art Gallery, for instance. Others have shifted the lens of empire away from Britain to India’s more ancient, pre-colonial pasts, like Splendours of the Subcontinent: A Prince’s Tour of India 1875–76 in 2018, and India and the World: A History in Nine Stories at the British Museum, partnered with the Barbican.

Solo shows have offered a small panacea—the 2016 Bhupen Khakhar retrospective You Can’t Please All, for instance. Or Chila Kumari Singh Burman’s 2020 Tate Britain public commission Remembering a Brave New World, which joyfully splashed the “master’s house” with Bollywood, Hindu mythology, and feminist iconography in neon. This month, Scottish Sikh artist Jasleen Kaur won the prestigious Turner Prize for an installation including family photos and a doily-covered car.

It is no secret that cultural institutions in the UK, most notably the British Museum, established in 1753, have faced mounting criticism for their complicity within long-held colonial frameworks, from their corporate sponsors to the foreign artifacts they hoard. The Barbican, while being a post-war institution, has itself come under fire for suppressing pro-Palestinian voices and perpetuating systemic racism amid its programming and staff while positioning itself as progressively engaging postcolonial cultures with nuance.

The Imaginary Institution of India is a watershed moment for the uneven history of Indian visual arts in the UK, and Indian historiography overall in the global exhibitions space. It generously marries political heft, institutional progression, historical rigor, and curatorial depth. As an Indian working in a foreign art world, I only see this kind of work growing—whether through more record-breaking cinema, exhibitions, books, or other media—imagining and reimagining what a nation could become.

The Imaginary Institution of India: Art 1975-1998 is at the Barbican Art Gallery in London from 5 October 2024 – 5 January 2025.

Related Posts

All We Imagine As India: On the Barbican’s Latest Exhibition

The verb “imagining”, to me, is one of the most significant in the human vocabulary. It comes from the Latin imaginari, meaning “to form a mental picture” or “to picture to oneself,” with the Proto-Indo-European root aim- or aimo- relating to copying, imitation, or representation. Imagination enables us to build ourselves off the past—our dreams, systems, relationships—so it’s what drives and catalyzes any political force.

In 1983, political scientist Benedict Anderson famously coined the term “imagined communities” to describe the concept of nations. He called the bluff, arguing that a nation is inherently imagined or made up, a group of men drawing up lines on a table. I could never possibly meet every member of my country, yet those lines and my place within them, dictated by a document, could bind us in solidarity, patriotism, or nostalgia. Dulce et decorum est pro patria mori (It is sweet and fitting to die for one’s country)—all for a social construct.

This year at London’s Barbican Centre, an exhibition titled The Imaginary Institution of India: Art 1975-1998 (5 October 2024 – 5 January 2025) unfurls those years in which Anderson was ideating and my mother was discovering Michael Jackson, migrating out of India to southern Africa, and having me—years that exist, to me, just in my imagination. The exhibition’s title comes from a 1991 book by Sudipta Kaviraj of the same name, which discusses the formation of India as a political entity—or imagined community—and how the nation evolved post-colonization.

Four themes mold the show: “the rise of communal violence, gender and sexuality, urbanization and shifting class structures, and a growing connection with Indigenism.” The mediums are varied, from traditional oil on canvas to giclée prints, video, multimedia installations, textiles, wood, pigments, cow dung, pastel, indigo, and more. Such a lush range of materiality offers a visceral connection with the actual, variegated land of India, albeit from afar. And it gives a shape, a concreteness, to the differing emotional paths the artworks lead viewers down.

Works by 30 Indian artists explore over two decades of instability, tearing, and suturing in the country—a period with immense resonance for India today under Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). The 1970s-90s saw independent India’s first brush with authoritarianism; similar suppression of dissent, targeting of dissidents, and a more concentrated centralization of power occur now. The BJP’s focal ideology of Hindu nationalism also saw its beginnings pre-millennium, its flashpoint being the Ram Janmabhoomi movement and the consequent demolition of the Babri Masjid in 1992.

It might be difficult to imagine the exhibition’s diverse lineup being allowed to be feted within India now. Jangarh Singh Shyam, Sheba Chhachhi, Tyeb Mehta, Gulammohammed Sheikh, Arpita Singh, Vivan Sundaram, Meera Mukherjee, Jitish Kallat, and more. There are established names, internationally undersung pioneers, and names that could have been buried, revivified here. For all their plurality, as well as many of their radical, leftist, and Marxist politics, these artists often appear in near-complete opposition to the BJP’s aggressive right-wing approaches, which, as we discover, many of these artists have felt in the past.

This may explain why the exhibition is not currently traveling to India. One of the nation’s premier contemporary art institutions, New Delhi-based Kiran Nadar Museum of Art, has offered generous support through loaning works and expertise as the Barbican’s collaborators but is not slated to host the show.

Competing Imaginations: Ambedkar, Hindutva, and the Colonial Specter

Emerging from the aftermath of brutal British colonialism and a traumatic partition in 1947, India—like most postcolonial nations—was a project in need of reimagining. The main custodian of this task, Dr. B.R. Ambedkar drafted one of the most detailed constitutions in the world, espousing democracy, secularism, inclusivity, and rule of law while eschewing divisive ways of belonging upon religion, caste, gender, or place of birth.

But if a country is an imagined community, even the strongest constitution struggles to cohere the thousand babbling interpretations of what that nation could be instead. What happens when one’s imagination conflicts with another, when people have differing notions of harmony, peace, or community? Where Ambedkar’s constitution sought to celebrate pluralism, reveling in the notion that there is no single, fixed “India” or “Indian”, others laid plans for a far more homogenous state, what scholar Sara Ahmed would call a “harder touch.”

For instance, Vinayak Damodar Savarkar’s 1923 pamphlet Essentials of Hindutva “called for Hindus, hopelessly divided by caste, to come together…and reclaim their ancient homeland from… outsiders, primarily the Muslims.” Savarkar’s views became central to the formation of the BJP’s parent organization, the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), which positions him as a “nationalist icon.”

The Imaginary Institution of India is bookended by two major historical events—the 1975 Emergency declared by then-Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, which temporarily suspended democracy through autocratic rule, and the 1998 Pokhran nuclear tests, which effectively made India a nuclear power. Economic and social upheaval abounded in both private and public spheres. High communal tensions, rising unemployment, and etched patriarchal, religious, and casteist divisions flared.

This period of Indian history has never been explored before, and so thoroughly, in a major arts institution. Most often, instead of spotlighting modern and contemporary artists responding to how India has shaped itself post-independence, UK institutions huddle in the perceived neutral safety of objects, ruins, and histories so old and distant they nearly defy imagination. This results in gorgeous yet faintly Orientalised and politically antiseptic shows, like the recent The Great Mughals: Art, Architecture and Opulence at the Victoria and Albert Museum, sumptuous as it is.

During my visit, I was instantly awed by the exquisite remnants displayed from the reigns of three Mughal emperors—Akbar, Jahangir, and Shah Jahan. About thirty minutes in, however, I noticed the awe of other people around me and simultaneously, the distance of feeling between us.

Every work on display was owned and kept outside the Indian subcontinent, in collections spanning the UK, North America, and the Gulf. I was staring at pieces of history that felt like they should have belonged to me too, to my imagined community. Yet, even in their presence, I felt a complicated sense of alienation and loss—a glass vitrine and an imperialist nation stood between us. It’s a cognitive discord filmmaker Mati Diop explores in this year’s magical documentary Dahomey, questioning the role of art and objects in nation formation and continuity.

The Imaginary Institution of India’s curator Shanay Jhaveri is “the first non-white and non-British person to serve as the Barbican’s Head of Visual Arts” since its establishment in 1982. For this show, he has worked alongside research associate Qamoos Bukhari, who is Kashmiri Muslim, and curatorial assistant Amber Li. Jhaveri’s appointment serves as a model not only for aspiring and early-career South Asian cultural practitioners but also for visually narrating a nation with both rigor and intimacy.

As Jhaveri states in a recent video, “This exhibition has been long overdue.”

Labor, Love, and India’s Workers

In The Imaginary Institution of India, there is no wall text. Small stacks of hot pink catalog booklets, the comfortable size of slim paperbacks, lie in wait at the entrance. Beside them is the opening artwork, Gieve Patel’s Two Men with Hand Cart (1979), donned by all the exhibition posters. It depicts two male laborers breaking to chat against a pink sky, with Bombay’s buildings burgeoning behind them. We presume they are part of the construction, this overwhelming execution of the imagination. An immediate tone is set: the show’s prevalent focus on workers’ lives, and those forgotten yet foundational to a country. A simultaneous sense of softness and pain is evoked by the pink—the color of a sunset’s aftermath.

Gieve Patel was primarily a physician, similar to Sudhir Patwardhan, a radiologist painter. The medical profession required enormous intimacy with the city’s poorest and sickest, resulting in constant close contact with the realities of the widening class divide and the healthcare system’s flaws. Alongside paintings by Patel and Patwardhan, Navjot Altaf’s Factory series (1982) addressing the 1982-83 textile strikes, and Nalini Malani’s video gaze on city slums, The Imaginary Institution of India often props Bombay as a microcosm of the country itself. The city-as-state’s workers, many of whom have migrated in thousands from rural homes, are foregrounded for viewers to experience the subjectivity of their daily lives, which are shaped but not solely defined by the value of their labor.

Although we see the various, grueling ways in which the country flushes its workers through its systems—like a heart does blood—these artworks also illuminate their subjects’ leisures, pleasures, and routines built around and off their work. For instance, photojournalist Pablo Bartholomew’s images of young people in Bombay and Delhi at the height of the Emergency portray the bits of life’s glitter youth especially seized within private spaces. They lounge, laugh, dance, smoke in bed, have debates, indulge in friendships, parties, and romance, following their desires away from a tense, repressive public environment that wants to constrain them.

Such themes form the nearly identical premise of this year’s Cannes Grand Prix-winning film All We Imagine As Light, directed by Malani’s daughter, Payal Kapadia. The multilingual film follows two female nurses and a cook, long-term migrants working in the same Mumbai hospital. Warm jazz and monsoon blues bathe these women as they live within their world’s hierarchies—urban gentrification, patriarchy, language, religion, and social taboos—while trying to experience love and pleasure in all forms. The movie is breathlessly beautiful, yet quietly scathing about the obstacles inhibiting free love among Indians across social strata, much like Arundhati Roy’s 1997 novel The God of Small Things.

An effective state might try to alleviate these divides. Yet over the years, India has seen the governance of different moneyed, hate-mongering thumbs; there is subtle continuity from The Imaginary Institution of India’s focal history to the present. The care with which it curatorially unfolds is nothing short of a rich screenplay like Kapadia’s or other unconventional filmmakers, many of whom are included in an accompanying film programme. This way, the exhibition also makes ideal use of the Barbican’s cinema model.

Indian Parallel Cinema in Dialogue with the Exhibition Space

The film programme chronicles the rise of Indian Parallel Cinema, one of South Asia’s first postcolonial film movements, which “gave agency to themes, narratives and groups … rendered invisible or marginalized on screen.” Among the included films are Amma Ariyan (dir. John Abraham, 1986), situated amid leftist political activity in Kerala; Deewaar (dir. Yash Chopra, 1975), which established the Angry Young Man trope popularized by Amitabh Bachchan, symbolizing a generation’s “collective angst…with socio-economic inequities”; and Ram Ke Naam (dir. Anand Patwardan, 1992), a documentary still restricted in India for exploring the Babri Masjid’s razing by a right-wing mob.

These films extend the conversations begun in the exhibition space. Further supplementing the well-researched, eloquently written catalog is a patient yet exhaustive audio guide that can be accessed from one’s phone. The experience of the exhibition becomes less of a tiring day at the museum then, to something more immersive, like submerging oneself within one of these films.

The Angry Young Man trope builds upon searing works by Patel, Patwardhan, Malini, and Altaf, among others. For instance, Altaf is also showing her 1976 Emergency Poster series, “inspired by the visual language of Cuban political propaganda” and meant to be used for activist demonstrations “against government corruption.” Free speech and dissidence—the existence of which measures a democracy’s health—are currently under heavy crackdown. Yet Altaf’s posters remind us that protest culture has existed, flourished, and evolved from its own distinct past in India.

Meanwhile, the themes of Ram Ke Naam expand a dialogue on communal politics fueled especially poignantly by M.F. Husain, one of India’s most renowned modern artists. He was forced into exile in 2006 largely due to threats from a Hindu nationalist group, the Vishwa Hindu Prasad, and the BJP.

Husain’s 1986 painting Safdar Hashmi depicts the killing of the titular political activist, actor, and playwright while performing a street play outside Delhi. Hashmi was a major theatre figure, founding the Jana Natya Manch, or “people’s theatre forum”, which “staged plays in public spaces and working-class neighborhoods to counter attempts by the ruling class to suppress dissent.”

Husain depicts Hashmi’s death with deep dignity and emotion while emphasizing its brutality—Hashmi’s limbs are broken severely, rigid scarlet lines ramming through the image. He is shown as less of a person than a vehicle of ideas so forceful and fearless it had to be shattered and taken apart.

I stood for a long while in front of this painting, my chest thick and full as if welling with water. The image before me did not feel new, yet Husain made it feel so. Today, social media and other digital platforms flood with visuals of public assaults and lynchings of Muslims for the tiniest “transgressions,” like possessing beef or simply walking down the street in parts of India. That they proliferate so much hardly radicalizes but inures us against their impact. The more ubiquitous the images, the quicker their force drains out of our collective vision.

But many of these artworks in The Imaginary Institution of India restore the viscerality of the pain, so cushioned by our algorithms, that we have long inflicted on each other. Artist Rummana Hussain, who had to flee her Bombay home amid riots following the Babri Masjid demolition, displays her 1993 series of broken terracotta pots, littered with gheru (powdered red clay) and rubble spilling on fragmented mirrors. The result is trauma as a kaleidoscope: the viewer sees shattered domes, bodies, land, and earth refracted together.

Towards Equality: Womanhood and Queerness

Where there was an Angry Young Man, there were many, many Angry Young Women. In 1974, a government report titled Towards Equality stated that women were “far from enjoying the rights…guaranteed to them by the constitution,” sparking a wave of nationwide women’s movements. Various female artists, each with their own feminist thinking and positionality within the country’s social landscape, created works in response. Some are more documentarian and radical, while others turn inward to desires, fantasies, and imaginings.

Part of these movements was Sheba Chhachhi, whose stunning black-and-white photographs Seven Lives and a Dream (1980-91) follow seven women activists protesting anti-dowry violence. What’s striking about the series is that—in addition to these intensely emotional images—Chhachhi returns to her subjects a decade later, letting themselves choose how they want to be photographed in the aftermath of who they once were. Some occupied the private sphere, surrounded by personal items like typewriters. Others retained being seen in the public arena. One activist named Sathyarani sat on the steps of the Indian Supreme Court; from here, she had spent decades fighting for justice for her murdered daughter.

Prominent artist Nilima Sheikh presents some standout works from The Imaginary Institution of India. Her series of 12 narrative paintings, made with tempera on Sanganeri paper, chronicles the life of a teenage girl named Champa, titled When Champa Grew Up (1984-5). The images are childlike and naive, yet their content is progressively harrowing. Sheikh personally knew the girl in the story, who was married as a child into an abusive family and eventually murdered by them for dowry-related issues.

The tale is disturbingly similar to one of the plots in Anita Desai’s 1999 novel Fasting, Feasting, in which a young Indian girl has to forgo an Oxford scholarship for marriage. Her husband treats her as a servant when she cannot bear children, and it is heavily implied that he and his family then burn her to death.

But the exhibition’s representation of Indian women is not just limited to trauma. Another of Sheikh’s works, an enormous double-sided painted canopy, forms an installation one can walk in and around to visit different life experiences of Indian women. Shamiana (1996), named for the South Asian ceremonial tent used for festive occasions, depicts moments of pleasure, community, solitude, dance, domesticity, suffering, and more. Sheikh’s work celebrates Indian women as whole, distinct subjects, rather than flat objects upon which society projects its pitfalls.

The Imaginary Institution of India approaches sexuality, too, with assertive joy and celebration above trauma. Since 1861, the colonial law Section 377 effectively criminalized homosexuality in India. It was only repealed in 2018, though queerness remains highly taboo. In Exiles (1987), photographer Sunil Gupta stages gay men at various New Delhi landmarks, with accompanying excerpts from their conversations. Some are snarky, some warm. At Nehru Park, the text reads: “Police operate here harassing people and intimidating them with beatings and extortion. Sometimes they just want a blow-job.” The series was never shown in India until 17 years later.

Similarly, queer artist Bhupen Khakhar’s work, particularly one of his finest paintings Two Men in Benares (1982), had to be stored away only two days after its unveiling at Bombay’s Gallery Chemould in 1987, fearing protests. The painting depicts two naked men entwined against a deep blue background, with smaller quotidian scenes around them. Benares, now Varanasi, is one of India’s holy cities for Hindus.

“By staging this sexual tryst within a religious context,” the catalog elegantly reads, Khakhar “knowingly props up the erotic against the sacred, and provocatively collapses the boundaries between private and public.” In Gupta’s photographs, Khakhar’s idylls, and elsewhere, there are wisps of utopia, imagining an alternative, dream world in which two men in Benares or Delhi can publicly love each other.

India’s Most Vulnerable: Caste, Indigeneity and the Environment

This yearning for a better elsewhere has only deepened with national dystopias. In 1984, one of the world’s worst chemical disasters occurred in Bhopal’s Union Carbide pesticide plant, spreading a dense, deadly gaseous fog all over the city. Thousands died within just three days and it is estimated that over 15,000 more succumbed in the following years, with countless more suffering from—and birthing children with—permanent disfigurements and disabilities. Pablo Bartholomew covered the incident and its aftermath for over 20 years. Four images from 1984, the immediate aftermath of the leak, are on show in The Imaginary Institution of India. Dead livestock abandoned on open land; a Union Carbide sign vandalized in red; a father burying his daughter.

The Bhopal tragedy presents a neat nexus of different issues that have plagued India from those decades to now, notably explored in Indra Sinha’s impeccable 2007 novel Animal’s People. The environmental disaster was attributed to human error, poor safety procedures, company negligence, and faulty equipment at an already understaffed plant. Union Carbide was a subsidiary of an American firm, which, along with the Indian government, has continually failed to take responsibility, properly clean up the site, or provide adequate compensation to victims even now. Fueling this decades-long catastrophe is the cruel, grinding engine of global capitalism, crushing all, but especially those most vulnerable.

To speak of India’s most vulnerable is to address its Adivasis, or indigenous and tribal inhabitants, and its Dalit population, among India’s most systematically marginalized. The Imaginary Institution of India dedicates decent space to Indigenous artworks, such as those by Jangarh Singh Shyam from the tribal Pardhan clan from Patangarh. Shyam depicts memories of his village life, drawing on its rituals, traditions, and myths to form a distinct visual vocabulary. This grows nostalgic as communities like his are impacted by capital-driven urbanization with many migrating to larger cities for work.

Similar themes emerge in Himmat Shah’s terracotta sculptures and Savindra Sawarker’s etchings of the daily lives of Dalit people. Sawarker became known for pioneering a Dalit and Ambedkarite artistic language, including iconography such as the matka (pot) and jhaadu (broom). Meanwhile, Shah was influenced by his birthplace of Lothal, Gujarat, one of the sites of the Indus Valley civilization. His use of clay stemmed from watching the Archaeological Survey of India excavate ancient pottery as a child and his own memories of the landscape. Through his sculpted heads, Shah “took an ancient material and brought it forward to give it a contemporary edge.”

The Master’s House: Indian Art in the UK

That such vast formal, historical, political, social, and cultural scope can be packed into a single exhibition’s portrait of a country at a particular time, is a more momentous feat than one can imagine. That it has arrived, the first of its kind, in the UK before India is unfortunate for those Indians who cannot see it in their own country, yet significant for the UK’s visual arts trajectory.

Beyond the mostly British critics who have reviewed the show favorably—albeit with distance from India itself as a political entity—what it could mean for British Indians, Indian diasporas, and visiting Indian audiences is as yet immeasurable. They have the potential to engage their country’s history as visualized by its diverse people, carrying its stories and lessons as beacons with which to navigate a fraught political present.

Indians comprise approximately three percent of the UK’s population and are its largest and most economically prosperous non-white demographic. Yet India as an educational and curatorial focus still manifests less as engaging with a complex country and more as a cabinet of curiosities for the British.

There have been some shows. A couple have focused directly on India and the UK’s colonial relationship while keeping Britain the primary locus—India in Britain: 1858–1950 and South Asian Modernists 1953–1963 at Whitworth Art Gallery, for instance. Others have shifted the lens of empire away from Britain to India’s more ancient, pre-colonial pasts, like Splendours of the Subcontinent: A Prince’s Tour of India 1875–76 in 2018, and India and the World: A History in Nine Stories at the British Museum, partnered with the Barbican.

Solo shows have offered a small panacea—the 2016 Bhupen Khakhar retrospective You Can’t Please All, for instance. Or Chila Kumari Singh Burman’s 2020 Tate Britain public commission Remembering a Brave New World, which joyfully splashed the “master’s house” with Bollywood, Hindu mythology, and feminist iconography in neon. This month, Scottish Sikh artist Jasleen Kaur won the prestigious Turner Prize for an installation including family photos and a doily-covered car.

It is no secret that cultural institutions in the UK, most notably the British Museum, established in 1753, have faced mounting criticism for their complicity within long-held colonial frameworks, from their corporate sponsors to the foreign artifacts they hoard. The Barbican, while being a post-war institution, has itself come under fire for suppressing pro-Palestinian voices and perpetuating systemic racism amid its programming and staff while positioning itself as progressively engaging postcolonial cultures with nuance.

The Imaginary Institution of India is a watershed moment for the uneven history of Indian visual arts in the UK, and Indian historiography overall in the global exhibitions space. It generously marries political heft, institutional progression, historical rigor, and curatorial depth. As an Indian working in a foreign art world, I only see this kind of work growing—whether through more record-breaking cinema, exhibitions, books, or other media—imagining and reimagining what a nation could become.

The Imaginary Institution of India: Art 1975-1998 is at the Barbican Art Gallery in London from 5 October 2024 – 5 January 2025.

SUPPORT US

We like bringing the stories that don’t get told to you. For that, we need your support. However small, we would appreciate it.