The Elgar prisoners’ latest hunger strike marks a momentous victory for prison rights

On 24 October, the lawyers and activists accused in the Elgar Parishad/Bhima Koregaon case were brought to court from Taloja Central Jail for their hearing. This bare minimum satisfaction of their basic legal right to be present for their case had become far from routine. It happened for the first time in nearly two months, after many hearings held in their absence, and despite specific directions from the court for their production. In fact, it took a hunger strike by seven of the accused—the latest of numerous protests by the BK-16 over the denial of bare necessities and basic rights—for the prison administration to concede to their demands. This latest strike stands out, not only for the significance of what was achieved, but for the manner in which it was executed and the swiftness with which it delivered success.

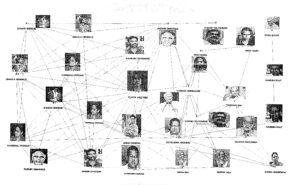

Six days before their production, on 18 October, the case had been listed for hearing, and they were not taken to court. That day, the seven men among the BK-16 who have still not been released on bail—Sudhir Dhawale, Surendra Gadling, Hany Babu, Rona Wilson, Sagar Gorkhe, Ramesh Gaichor and Mahesh Raut—launched their hunger strike.

Despite being incarcerated in different barracks of Taloja Central Jail, the seven prisoners somehow manoeuvred their way to the jail compound’s inner main gate, bypassing various internal checkpoints to be within earshot of the prison superintendent and senior jailers, and raised slogans against the Mumbai Police for not producing them in court. The prisoners raised slogans from the inner main gate, collectively, announcing an indefinite hunger strike.

It is important to stress the significance of this protest. Usually, to go anywhere near the two main gates of a prison, where the main offices of the superintendent, deputy superintendent and two or three senior jailors are located, even a single prisoner needs to take special permission from the jailor in charge of the circle in which he is lodged.

A typical circle comprises many yards, and in turn, each yard consists of several barracks, each of which houses hundreds of prisoners. Often, it takes hours to even access the circle jailor, for which a prisoner has to first go through the warder of his barrack, and then through the constable and head constable in charge of the yard. The warders are usually convicts themselves who are entrusted with security and other tasks, in the capacity of an accountable official, whereas constables are regular employees reporting to the jailor, or the head constable.

For prisoners branded as “naxals” in Maharashtra prisons, the jailors seldom permit their movements outside the respective yard of barracks, much less outside the circle. In large prisons, like the one at Taloja, there is more than one circle, and movements of prisoners from within any of the circles towards the jail gate would be severely restricted and controlled with utmost caution. Only if a certain individual or a category of prisoners had proven themselves to be trustworthy would the strictures be relaxed to some extent.

The question of allowing prisoners to go towards the inner jail gate, or even close to it, does not arise. It would require an individual prisoner to have some urgent and bona fide work to be conducted in the jail office, situated right between the prison’s huge outer and inner gates, for such an exception to be made. Even when prisoners attend meetings with their visitors, the prison officials take great care to ensure that the inmates do not loiter around anywhere. Casually approaching the inside of the inner gate is never an option. Even when a jailor or senior jailor in charge of a circle allows a prisoner to go to the jail office, they remain under constant observation, with “naxal” prisoners escorted by an accountable officer, whether a constable or a warder.

The fact that seven Elgar Parishad/Bhima Koregaon accused succeeded in making their way to the inner gate from different barracks to raise their protest is remarkable, to say the least.

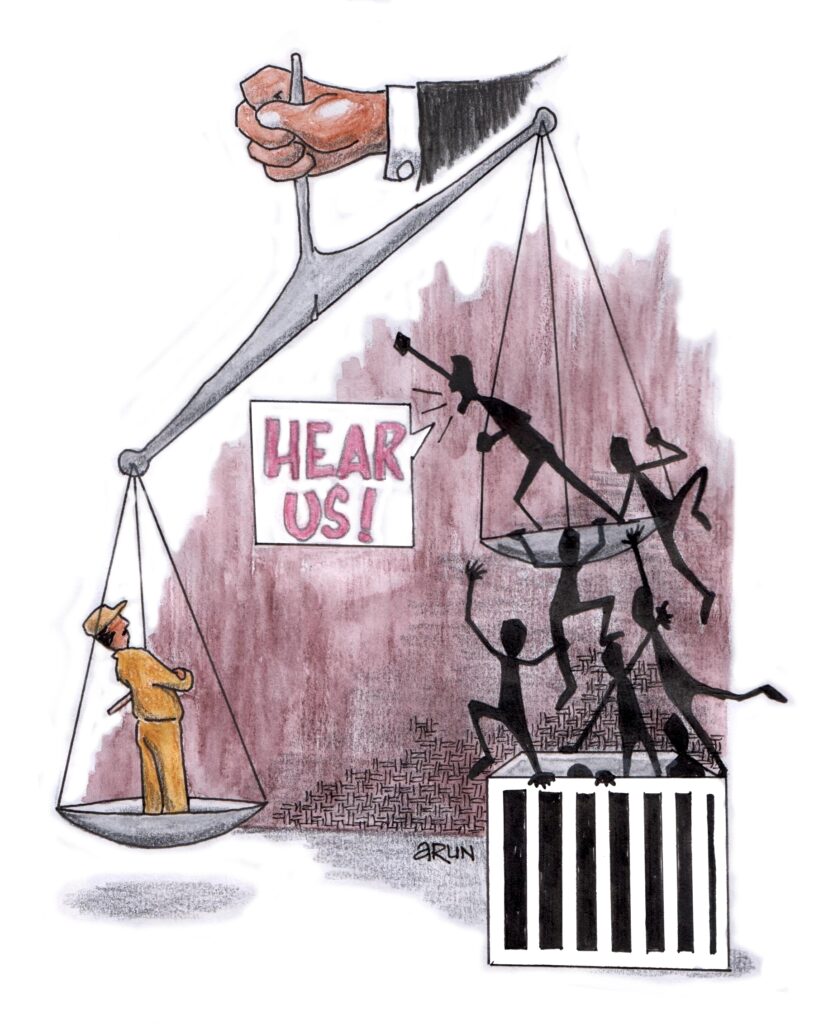

While the how remains a mystery, there are no two opinions about the why—production in court is a basic legal right of all prisoners under normal circumstances. Among the Elgar Parishad prisoners, this denial is particularly consequential for Surendra Gadling, a renowned lawyer who has been consistently representing himself in court during the proceedings. The prison and police officials’ failure to produce him in court without any sound reason for nearly two months is a violation of his fundamental right to a free and fair trial guaranteed under Article 21 of the Constitution.

The Elgar Parishad case, though currently in the pre-trial stage, has proceedings, including challenges to the chargesheet, being heard before the special NIA court adjudicating it. Moreover, there are also other proceedings, including two to quash the case, filed separately by Rona Wilson and on behalf of late Stan Swamy, pending before the Bombay High Court. For the Elgar Parishad accused who have not yet been released on bail—the seven men and Jyoti Jagtap, held in Byculla Women’s Jail—the non-production amounted to a vital severing of links with their lawyers and the ongoing judicial process. Despite the stipulations in the statutes and the pressing need for their court production to continue, the Commissioner of Police for Navi Mumbai refused to comply, citing a paucity of personnel to escort the prisoners to court.

It is important to contextualise the sudden non-production by the prison and police officials. After a recent spate of protests against corrupt practices within the prison, the assertion of the seven male undertrial prisoners inside the Taloja prison had escalated. In July, Sagar Gorkhe filed a complaint to the Navi Mumbai Police Commissioner accusing the senior jailor, Sunil Patil, of rampant corruption in running the jail canteen. Gorkhe noted that Patil was preparing lavish dishes to be sold at high prices to the wealthy prisoners, at the cost of the other prisoners. “This is eating into the ration for all prisoners, and the quality of food being given to other prisoners has deteriorated,” Gorkhe wrote in the complaint.

Gorkhe and Mahesh Raut had raised the issue with the prison authorities first. In response, on 18 June, Patil reportedly summoned the duo into the superintendent’s office and threatened them to stay out of the matter, warning them of dire consequences. Patil had turned the jail canteen that is supposed to be run on a “no profit, no loss” basis into a “business worth lakhs,” the Kabir Kala Manch activist noted.

Then, on 30 July, Surendra Gadling filed a complaint before the Maharashtra police’s Anti-Corruption Bureau. Gadling reiterated Gorkhe, stating that Patil used rations meant for the general prison population to prepare special dishes for the wealthy prisoners, and made exorbitant profits in the process. Gadling’s complaint even detailed the logistics of the corrupt practice. He noted that while most jail inmates can only use a Prisoners Personal Cash account for any purchases, which is capped at Rs 10,000, the wealthy inmates are allowed to smuggle in cash to pay for their lavish dishes. According to the complaint, Patil would take 40 percent of the cash as his own cut, from which he would give 10 percent to the jail middleman who would give the remaining 60 percent to the wealthy prisoners.

Gadling and Gorkhe continued to escalate the issue in August, with complaints to the police, the court and the Deputy Inspector General of Prisons in Maharashtra, while protests continued within the prison. Gadling also accused Patil of forging a complaint, under Gadling’s name, against some gangsters inside the prison. These gangsters were known for indulging with prison officials to procure the exorbitantly priced lavish meals prepared by Patil. But Gadling responded promptly with a written complaint recording Patil’s forgery, a copy of which I have seen, adding that it was an attempt to create a rift between the gangsters and the political prisoners accused in the Elgar Parishad case.

Gadling’s quick submission averted the possibility of the gangsters turning against them. Among long-time jail servers, it is common knowledge that such misunderstandings among disparate prisoners are routinely created by some administrators, as part of a time-tested divide-and-rule practice. Following the complaints, the prison administration requested the Elgar Parishad prisoners, especially Gadling, to withdraw the corruption and forgery complaints. None of them has reportedly agreed to strike any sort of compromise with the officials.

The next month, in the wake of media reports on the corrupt practices in prison and the protests against those, the Navi Mumbai Police unilaterally suspended the seven prisoners’ production in court. Yet, the morale of the political prisoners vis-a-vis the prison administration is said to be higher than ever before, since the latter initiated efforts to strike a compromise. Moreover, in early July, those among the Elgar Parishad prisoners lodged in the high-security Anda cell at Taloja were removed to the common barracks, ending their segregation from the rest of the prisoners. While the reason given was that the high-security enclosure needed to be demolished for repairs, it is pertinent to note that it is the newest one in the state.

The hunger strike, too, must be seen in the context of these developments between the political prisoners and the prison authorities. On 19 October, within 24 hours of them launching the protest, the political prisoners were assured that their court production would resume. This decision would likely have required consultation between the Navi Mumbai Police, the Taloja prison authorities, and the National Investigation Agency, which is prosecuting the case. The fact that this assurance was provided within a day speaks of the powerful impact of the protests and activism of the political prisoners from within jail. Following the assurance, the seven prisoners unanimously withdrew their hunger strike. They were all produced on the next scheduled date, five days later.

In the BK-16 Prison Diaries project, a series of essays by the Elgar Parishad prisoners published by The Polis Project, Ramesh Gaichor and Varavara Rao have written about the importance and necessity of hunger strikes inside the same prison. Gaichor writes:

The struggle against the prison is a daily occurrence here. Every day, the system creates new obstacles, new rules, new problems. Thus, this ongoing battle is composed of several varied struggles. There were never any alternatives but to struggle.

Among the various strikes listed in his essay from prison, Gaichor refers to a struggle launched by Sudhir Dhawale, Sagar Gorkhe and Gautam Navlakha (since released on bail) against the illegal feudal custom of prisoners being compelled to remove their footwear when standing before the prison superintendent or other senior officers. There is no such rule in the Prison Manual. He also refers to hunger strikes for adequate water for the prisoners, against the lack of any facilities for relatives of prisoners who came for prison visits, to start the system of phone calls, and against the absence of necessary medical treatment, too.

Gaichor also notes “the struggle in the video conferencing court against the superintendent’s arbitrary, revengeful, wrongful use of his post to arbitrarily decide against sending us to court despite a judicial order for production in court.” Observing the increasing prevalence of such protests, Varavara Rao writes in his essay:

Interestingly, for the first time in the history of political prisoners all over the country, we now see indefinite hunger strikes against corruption, unworthy food being supplied, solitary confinement and 24-hour lock-ups, transfers to distant prisons, not being allowed to sit for exams etc. It has spread from Taloja to the central prisons of Hyderabad (Chanchalguda), Kerala, and Bihar.

Those who resorted to hunger strikes, even on genuine issues, were routinely segregated from other prisoners, often transferred to another barrack, or even a distant jail. To justify the arbitrary transfers, hunger strikers were usually referred to as “machaandis,” meaning trouble-makers, those who created a ruckus over trivial or non-issues. And Gaichor writes, “We Elgar prisoners have led many a machaand.”

While not all the protests have been as successful, this time, the weapon of a hunger strike fetched a positive response with the quick decision to resume the court production, despite the ruse of a paucity of police personnel.

Related Posts

The Elgar prisoners’ latest hunger strike marks a momentous victory for prison rights

On 24 October, the lawyers and activists accused in the Elgar Parishad/Bhima Koregaon case were brought to court from Taloja Central Jail for their hearing. This bare minimum satisfaction of their basic legal right to be present for their case had become far from routine. It happened for the first time in nearly two months, after many hearings held in their absence, and despite specific directions from the court for their production. In fact, it took a hunger strike by seven of the accused—the latest of numerous protests by the BK-16 over the denial of bare necessities and basic rights—for the prison administration to concede to their demands. This latest strike stands out, not only for the significance of what was achieved, but for the manner in which it was executed and the swiftness with which it delivered success.

Six days before their production, on 18 October, the case had been listed for hearing, and they were not taken to court. That day, the seven men among the BK-16 who have still not been released on bail—Sudhir Dhawale, Surendra Gadling, Hany Babu, Rona Wilson, Sagar Gorkhe, Ramesh Gaichor and Mahesh Raut—launched their hunger strike.

Despite being incarcerated in different barracks of Taloja Central Jail, the seven prisoners somehow manoeuvred their way to the jail compound’s inner main gate, bypassing various internal checkpoints to be within earshot of the prison superintendent and senior jailers, and raised slogans against the Mumbai Police for not producing them in court. The prisoners raised slogans from the inner main gate, collectively, announcing an indefinite hunger strike.

It is important to stress the significance of this protest. Usually, to go anywhere near the two main gates of a prison, where the main offices of the superintendent, deputy superintendent and two or three senior jailors are located, even a single prisoner needs to take special permission from the jailor in charge of the circle in which he is lodged.

A typical circle comprises many yards, and in turn, each yard consists of several barracks, each of which houses hundreds of prisoners. Often, it takes hours to even access the circle jailor, for which a prisoner has to first go through the warder of his barrack, and then through the constable and head constable in charge of the yard. The warders are usually convicts themselves who are entrusted with security and other tasks, in the capacity of an accountable official, whereas constables are regular employees reporting to the jailor, or the head constable.

For prisoners branded as “naxals” in Maharashtra prisons, the jailors seldom permit their movements outside the respective yard of barracks, much less outside the circle. In large prisons, like the one at Taloja, there is more than one circle, and movements of prisoners from within any of the circles towards the jail gate would be severely restricted and controlled with utmost caution. Only if a certain individual or a category of prisoners had proven themselves to be trustworthy would the strictures be relaxed to some extent.

The question of allowing prisoners to go towards the inner jail gate, or even close to it, does not arise. It would require an individual prisoner to have some urgent and bona fide work to be conducted in the jail office, situated right between the prison’s huge outer and inner gates, for such an exception to be made. Even when prisoners attend meetings with their visitors, the prison officials take great care to ensure that the inmates do not loiter around anywhere. Casually approaching the inside of the inner gate is never an option. Even when a jailor or senior jailor in charge of a circle allows a prisoner to go to the jail office, they remain under constant observation, with “naxal” prisoners escorted by an accountable officer, whether a constable or a warder.

The fact that seven Elgar Parishad/Bhima Koregaon accused succeeded in making their way to the inner gate from different barracks to raise their protest is remarkable, to say the least.

While the how remains a mystery, there are no two opinions about the why—production in court is a basic legal right of all prisoners under normal circumstances. Among the Elgar Parishad prisoners, this denial is particularly consequential for Surendra Gadling, a renowned lawyer who has been consistently representing himself in court during the proceedings. The prison and police officials’ failure to produce him in court without any sound reason for nearly two months is a violation of his fundamental right to a free and fair trial guaranteed under Article 21 of the Constitution.

The Elgar Parishad case, though currently in the pre-trial stage, has proceedings, including challenges to the chargesheet, being heard before the special NIA court adjudicating it. Moreover, there are also other proceedings, including two to quash the case, filed separately by Rona Wilson and on behalf of late Stan Swamy, pending before the Bombay High Court. For the Elgar Parishad accused who have not yet been released on bail—the seven men and Jyoti Jagtap, held in Byculla Women’s Jail—the non-production amounted to a vital severing of links with their lawyers and the ongoing judicial process. Despite the stipulations in the statutes and the pressing need for their court production to continue, the Commissioner of Police for Navi Mumbai refused to comply, citing a paucity of personnel to escort the prisoners to court.

It is important to contextualise the sudden non-production by the prison and police officials. After a recent spate of protests against corrupt practices within the prison, the assertion of the seven male undertrial prisoners inside the Taloja prison had escalated. In July, Sagar Gorkhe filed a complaint to the Navi Mumbai Police Commissioner accusing the senior jailor, Sunil Patil, of rampant corruption in running the jail canteen. Gorkhe noted that Patil was preparing lavish dishes to be sold at high prices to the wealthy prisoners, at the cost of the other prisoners. “This is eating into the ration for all prisoners, and the quality of food being given to other prisoners has deteriorated,” Gorkhe wrote in the complaint.

Gorkhe and Mahesh Raut had raised the issue with the prison authorities first. In response, on 18 June, Patil reportedly summoned the duo into the superintendent’s office and threatened them to stay out of the matter, warning them of dire consequences. Patil had turned the jail canteen that is supposed to be run on a “no profit, no loss” basis into a “business worth lakhs,” the Kabir Kala Manch activist noted.

Then, on 30 July, Surendra Gadling filed a complaint before the Maharashtra police’s Anti-Corruption Bureau. Gadling reiterated Gorkhe, stating that Patil used rations meant for the general prison population to prepare special dishes for the wealthy prisoners, and made exorbitant profits in the process. Gadling’s complaint even detailed the logistics of the corrupt practice. He noted that while most jail inmates can only use a Prisoners Personal Cash account for any purchases, which is capped at Rs 10,000, the wealthy inmates are allowed to smuggle in cash to pay for their lavish dishes. According to the complaint, Patil would take 40 percent of the cash as his own cut, from which he would give 10 percent to the jail middleman who would give the remaining 60 percent to the wealthy prisoners.

Gadling and Gorkhe continued to escalate the issue in August, with complaints to the police, the court and the Deputy Inspector General of Prisons in Maharashtra, while protests continued within the prison. Gadling also accused Patil of forging a complaint, under Gadling’s name, against some gangsters inside the prison. These gangsters were known for indulging with prison officials to procure the exorbitantly priced lavish meals prepared by Patil. But Gadling responded promptly with a written complaint recording Patil’s forgery, a copy of which I have seen, adding that it was an attempt to create a rift between the gangsters and the political prisoners accused in the Elgar Parishad case.

Gadling’s quick submission averted the possibility of the gangsters turning against them. Among long-time jail servers, it is common knowledge that such misunderstandings among disparate prisoners are routinely created by some administrators, as part of a time-tested divide-and-rule practice. Following the complaints, the prison administration requested the Elgar Parishad prisoners, especially Gadling, to withdraw the corruption and forgery complaints. None of them has reportedly agreed to strike any sort of compromise with the officials.

The next month, in the wake of media reports on the corrupt practices in prison and the protests against those, the Navi Mumbai Police unilaterally suspended the seven prisoners’ production in court. Yet, the morale of the political prisoners vis-a-vis the prison administration is said to be higher than ever before, since the latter initiated efforts to strike a compromise. Moreover, in early July, those among the Elgar Parishad prisoners lodged in the high-security Anda cell at Taloja were removed to the common barracks, ending their segregation from the rest of the prisoners. While the reason given was that the high-security enclosure needed to be demolished for repairs, it is pertinent to note that it is the newest one in the state.

The hunger strike, too, must be seen in the context of these developments between the political prisoners and the prison authorities. On 19 October, within 24 hours of them launching the protest, the political prisoners were assured that their court production would resume. This decision would likely have required consultation between the Navi Mumbai Police, the Taloja prison authorities, and the National Investigation Agency, which is prosecuting the case. The fact that this assurance was provided within a day speaks of the powerful impact of the protests and activism of the political prisoners from within jail. Following the assurance, the seven prisoners unanimously withdrew their hunger strike. They were all produced on the next scheduled date, five days later.

In the BK-16 Prison Diaries project, a series of essays by the Elgar Parishad prisoners published by The Polis Project, Ramesh Gaichor and Varavara Rao have written about the importance and necessity of hunger strikes inside the same prison. Gaichor writes:

The struggle against the prison is a daily occurrence here. Every day, the system creates new obstacles, new rules, new problems. Thus, this ongoing battle is composed of several varied struggles. There were never any alternatives but to struggle.

Among the various strikes listed in his essay from prison, Gaichor refers to a struggle launched by Sudhir Dhawale, Sagar Gorkhe and Gautam Navlakha (since released on bail) against the illegal feudal custom of prisoners being compelled to remove their footwear when standing before the prison superintendent or other senior officers. There is no such rule in the Prison Manual. He also refers to hunger strikes for adequate water for the prisoners, against the lack of any facilities for relatives of prisoners who came for prison visits, to start the system of phone calls, and against the absence of necessary medical treatment, too.

Gaichor also notes “the struggle in the video conferencing court against the superintendent’s arbitrary, revengeful, wrongful use of his post to arbitrarily decide against sending us to court despite a judicial order for production in court.” Observing the increasing prevalence of such protests, Varavara Rao writes in his essay:

Interestingly, for the first time in the history of political prisoners all over the country, we now see indefinite hunger strikes against corruption, unworthy food being supplied, solitary confinement and 24-hour lock-ups, transfers to distant prisons, not being allowed to sit for exams etc. It has spread from Taloja to the central prisons of Hyderabad (Chanchalguda), Kerala, and Bihar.

Those who resorted to hunger strikes, even on genuine issues, were routinely segregated from other prisoners, often transferred to another barrack, or even a distant jail. To justify the arbitrary transfers, hunger strikers were usually referred to as “machaandis,” meaning trouble-makers, those who created a ruckus over trivial or non-issues. And Gaichor writes, “We Elgar prisoners have led many a machaand.”

While not all the protests have been as successful, this time, the weapon of a hunger strike fetched a positive response with the quick decision to resume the court production, despite the ruse of a paucity of police personnel.

SUPPORT US

We like bringing the stories that don’t get told to you. For that, we need your support. However small, we would appreciate it.