The battle to protect Adivasis’ right to the land – A profile of Father Stan Swamy

“At no time have governments been moralists. They never imprisoned people and executed them for having done something. They imprisoned and executed them to keep them from doing something. They imprisoned all those prisoners of war, of course, not for treason to the motherland…They imprisoned all of them to keep them from telling their fellow villagers about Europe. What the eye doesn’t see, the heart doesn’t grieve for.”

― Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, The Gulag Archipelago, 1918-1956

‘Political Prisoner’ is a category of criminal offense that sits most egregiously in any civilized society, especially in countries that call themselves liberal democracies. It is a thought crime: the crime of thinking, acting, speaking, probing, reporting, questioning, demanding rights, and, more importantly, exercising one’s citizenship. But these inhumane incarcerations do not just target private acts of courage, they are bound together with the fundamental questions of citizenship, and with people’s capacity to hold the State accountable. Especially States that are unilaterally and fundamentally remaking their relationship with their people. The assault on the fundamental rights has been consistent and ongoing at a global level and rights-bearing citizens are transformed into consuming subjects of a surveillance State.

In this transforming landscape, dissent is sedition, and resistance is treason.

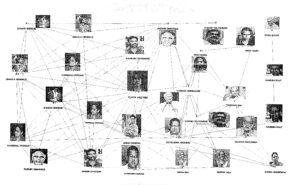

While the Indian State has a long history of ruthlessly crushing dissent, a new wave of arrests began in 2018. Eleven prominent writers, poets, activists, and human rights defenders have been in prison, held under the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act. They are accused of being members of a banned Maoist organization, plotting to kill Prime Minister Narendra Modi, and inciting violent protests in Bhima Koregaon. To date, no credible evidence has been produced by the investigating agency, and those accused remain incarcerated without bail. Since the anti-Citizenship Amendment Act protest began in December 2019, students, activists, and peaceful protesters have been charged with sedition, targeted with violence, and subjected to arrests. Since then, more arrests have followed specifically targeting local Muslim students leader and protestors, including twenty-seven-year-old student leader Safoora Zargar, who is currently pregnant.

Since the COVID-19 lockdown was announced, India’s leading public intellectuals, opposition leaders, writers, thinkers, activists, and scholars have written various appeals to the Narendra Modi government for the release of India’s political prisoners. They are vulnerable to COVID-19 contagion in the country’s overcrowded jails, where three coronavirus-related deaths have already been reported. In response, the State has doubled down and rejected all the bail applications. It also shifted the seventy-year-old journalist Gautham Navlakha from Delhi’s Tihar Jail to Taloja, without any notice or due process – Taloja is one of the prisons where a convict has already died of COVID-19.

A fearful, weak State silences the voice of dissent. Once it has established repression as a response to critique, it has only one way to go: become a regime of authoritarian terror, where it is the source of dread and fear to its citizens.

How do we live, survive, and respond to this moment?

In collaboration with maraa, The Polis Project is launching Profiles of Dissent. This new series centers on remarkable voices of dissent and courage, and their personal and political histories, as a way to reclaim our public spaces.

Profiles of Dissent is a way to question and critique the State that has used legal means to crush dissent illegally. It also intends to ground the idea that, despite the repression, voices of resistance continue to emerge every day.

You can read Varavara Rao’s profile here, the profile of Sudha Bharadwaj here, that of GN Saibaba here, Gautham Navlakha’s profile here, Anand Teltumbde here, Sharjeel Usmani here, Shoma Sen here, Surendra Gadling here, Asif Iqbal Tanha here, Rona Wilson here, Sudhir Dhawale here, Sharjeel Imam here, Arun Ferreira here and Umar Khalid here.

FATHER STAN SWAMY

Fr. Stan Swamy is an indigenous people’s rights defender. He is the founder of Vistapan Virodhi Janvikash Andolan (VVJA), an all India platform for different movements that are campaigning against human rights violations caused by the displacement of Adivasis, Dalits, and farmers from their lands. The platform has supported vulnerable communities faced with displacement from extractive industry projects in securing their land rights and proposing sustainable development models instead. Swamy has also been involved in numerous fact-finding missions including putting together a report highlighting the illegal methods used by the government against Dalits and Adivasis.

According to the report ninety-seven percent of the 102 under- trials accused of being Maoists or “helpers of Maoists” when interviewed, reiterated that allegations against them were wrong. A large number of fake cases under the Unlawful Activities Prevention Act (UAPA) and stringent sections of the Indian Penal code were imposed upon Adivasis and Dalits without evidence. About 96% of the respondents earned less than Rs 5,000 a month—indicating low productivity of their landholdings. The study exposed the misuse of criminal justice procedures to repress the under trial detainees in the prisons. A large proportion of acquittals further corroborate the routine harassment that many innocent Adivasis are put through in the name of quashing “Maoism”.

Date of raids: 28 August 2018 and 12 June 2019

Charges: Father Stan Swamy’s house was raided in the morning on 28th August 2018. The police confiscated his laptop, mobile phone, and CDs. He was raided based on a fabricated connection to the Bhima Koregaon violence and his connection to Elgaar Parishaad. The police came to my house with something written in Marathi” and didn’t even bother to provide a copy of this FIR in which they named me,” Swamy said at a press conference, organised after the raids on Tuesday at his house in Bagaicha in Ranchi’s Namkum area to express support for those arrested and raided by teams of the Pune Police. “I neither have any connection with Elgar Parishad nor the violence that took place in Bhima Koregaon in January.” Dubbing the police action against eminent scholars and social activists a “naked dance of power”, Father Swamy said that while he personally knew Sudha Bharadwaj, Arun Ferreira and Vernon Gonsalves—who were among the activists whose homes were raided in connection with the Bhima Koregaon investigation—he has no connection with the others who were arrested. “Freedom of dissent is being suppressed by the government, which bodes ill for the future of the country,” he warned.

Update 12 October 2020: On 12 June 2019, an eight-member team of the Pune city police raided Father Stan Swamy in the early hours for the second time since August 2018. Swamy was questioned multiple times by the NIA at his residence in Bagaicha and according to him was interrogated for fifteen hours at a stretch. In the charge sheet, the agency has claimed that he is a CPI (Maoist) cadre and was actively involved in its activities. It was also claimed that he was in communication with other cadres and had received funds from them. The NIA also claimed that he was a convenor of the Persecuted Prisoners Solidarity Committee (PPSC), which it claimed was a frontal organization of CPI (Maoists). The NIA has also claimed that it had recovered incriminating documents, literature, and propaganda from him. Swamy has denied these charges , allegations of Maoist links, and said in the video that he recorded before his arrest has never been to Bhima Koregaon. In a statement, Swamy stated that the NIA placed several documents before him claiming they were taken from his computer implicating his connection to Maoists. “I told them all these were fabrications stealthily put into my computer and I disowned them.”

“I would just add that what is happening to me is not unique. Many activists, lawyers, writers, journalists, student leaders, poets, intellectuals, and others who stand for the rights of Adivasis, Dalits, and the marginalized and express their dissent to the ruling powers of the country are being targeted,” he said.

On 9 October 2020, Father stan Swamy was flown to Mumbai from Ranchi and produced before the court. The NIA did not seek his custody. Swamy was sent to judicial custody till 23 October in the middle of a global pandemic.

You can watch the video he recorded before his arrest here:

Location of work: Jharkhand

Fr. Stan Swamy: The Jharkhand Priest who made People his Religion by Sushmita

On the morning of August 28 just as the people of Ranchi city were waking up to a clear sky after heavy downpours in the previous days, and preparing themselves for the day’s chores, they were taken aback by the abrupt raid on the home of Father Stan Swamy, one of the city’s prominent social and political activists.

The Bagaicha campus, which is also the residence of Father Stan Swamy, was raided by the Maharashtra and Jharkhand police around 6 am and the search operations continued for several hours. The police confiscated Father Stan’s mobile, laptop, some audio cassettes, some CDs, and a recent press release on the Pathalgadi movement by Women against Sexual Violence and State repression (WSS). Father Stan was not told about the details of the charges against him. The police video-recorded the entire event.

This raid comes just a few weeks after Father Stan and 19 other persons including activists, journalists and intellectuals were booked on charges of sedition by the Jharkhand government. The police have cited their Facebook posts as evidence of their role in the Pathalgadi movement in Khunti. Among other sections, they have been booked under 66A of the Information Technology Act, 2000 which was repealed by the Supreme Court in 2015!

Rapid industrialization in Jharkhand

Ranchi, the capital city of Jharkhand, is a city with developmental aspirations. The landscape can be seen slowly transforming after it became the capital of the newly formed Jharkhand state in 2000. It accounts for more than 40% of the mineral resources of India, but it suffers widespread poverty as 39.1% of the population is below the poverty line and 19.6% of the children under five years of age are malnourished. The state is primarily rural, with only 24% of the population living in cities. The interests of Adivasis were never taken into account and the state saw several unstable and allegedly corrupt governments. But the exploitation of Adivasis especially increased after the BJP government came to power at the centre in 2014 and the aspirations of industrialization have seen an aggressive push by the state government since then. About 209 MoUs worth Rs. 3 lakh crores were signed last year itself, in an Investors Summit held in Ranchi in 2017. Rapid industrialization meant land had to be occupied and the rich minerals excavated from Jharkhand’s soil, by hook or crook, by legal or illegal mechanisms. It appears that force, rather than dialogue and negotiations has been given preference over everything with thousands of people displaced from their lands without adequate compensation or rehabilitation.

Owner of the land is also the owner of sub-soil mineral

The SC order that ‘Owner of the land is also the owner of sub-soil mineral’ [SC: Civil Appeal No 4549 of 2000] wherein the SC said that.We are of the opinion that there is nothing in”

the law which declares that all mineral wealth sub- soil rights vest in the State, on the other hand, the ownership of sub-soil/mineral wealth should normally follow the ownership of the land, unless the owner of the land is deprived of the same by some valid process”. Despite this, the rich land possessed by Adivasis have come under severe attack. And though the Supreme Court declared 214 out of the 219 coal blocks in the country illegal, ordering their closure and levying a fine, the Central and state governments allegedly re-allot the illegal mines through auction to make it look legal.

Father Stan Swamy’s extensive work

It is in this context that Father Stan Swamy has extensively worked in Jharkhand for the rights of the Adivasis. One of the major campaigns he was associated with was the Jharkhand Organisation Against Uranium Radiation (JOAR), a campaign against Uranium Corporation India Limited in 96. The campaign successfully stopped the construction of a tailing dam in Chaibasa which, if constructed, would lead to the displacement of adivasis in Jadugoda’s Chatikocha area. After vociferously raising these issues, he moved to work with the displaced people of Bukaro, Santhal Parganas and Koderma and has continued to work for them.

The plight of under-trials and fabricated arrests in Jharkhand

In 2010 he published a book titled, ‘Jail Mein Band Qaidiyon ka Sach’ exposing the arbitrary

and unlawful arrests of tribal youths with alleged links to the Naxal Movement. In his book, he highlighted that in 97% of the cases, the family income of the youths arrested was less than Rs. 5000 and they could not even afford lawyers to represent their cases. In 2014 when a report was published discussing the plight of the arrested youths, Father Stan came into the State machinery’s radar. According to the report 98% of the 3000 arrested were falsely implicated and had no links to the Naxal Movement. Some served years in jail without a trial. He has selfless contributed to pay for the youth’s bail bonds and approached lawyers to represent these cases in the court of law.

Uncomfortable questions

Father Stan Swamy was questioning the non- implementation of the Vth Schedule of the Constitution that stipulates that a ‘Tribes Advisory Council’ (TAC) composed solely of members from the Adivasi community should be constituted and it would advise the Governor of the State about the well being and development of the Adivasi communities. However, Father believed that despite seven decades since the Constitution came into force, none of the Governors (the discretionary heads of these councils) ever reached out to Adivasis to understand and work on their problems. Father also highlighted how Panchayats (Extension to Scheduled Areas) Act [PESA], 1996 was “neatly ignored” and “had deliberately been left unimplemented in all the nine states.” This Act, for the first time recognized the fact that the Adivasi communities in India have had a rich social and cultural tradition of self governance through the Gram Sabha. He tirelessly organised the adivasis to fight for the rights granted to them under (PESA). This transpired into the Pathalgadi movement in 2017. The Pathalgadi movement played an important role in highlighting the State’s methodical negligence to implement PESA. About the movement he said something very crucial: “As for the Pathalgadi issue, I have asked the question ‘Why are Adivasis doing this?’ I believe they have been exploited and oppressed beyond tolerance. The rich minerals which are excavated in their land have enriched outsider industrialists and businessmen and impoverished the Adivasi people to the extent there are starvation deaths taking place.”

Father Stan questioned the silence of the government on the Samatha Judgement 1997 of the Supreme Court which provided significant safeguards for the Adivasis to control the excavation of minerals in their lands and to help develop themselves. The judgment came at a time when consequent to the policy of globalization, liberalization, privatisation, national and international corporate houses started to invade particularly the Adivasi areas in central India to mine the mineral riches. Not only this, Father Stan questioned the lack of implementation of the Forest Rights Act (FRA) 2006. As per his findings, from 2006 to 2011, about 30 lakh applications were made under FRA all over the country for title-deeds, of which 11 lakhs were approved but 14 lakhs were rejected and five lakhs were pending. He also found out that the Jharkhand govt is trying to bypass the Gram Sabha in the process of acquiring forest land for industrial set up. More recently, he was questioning the recently enacted Amendment to “Land Acquisition Act 2013” by Jharkhand govt. Which he called as “death knell” for the Adivasis. He insisted that it did away with the requirement for “Social Impact Assessment” which was aimed at safeguarding the environment, social relations and cultural values of affected people. The most damaging factor, in his words, is that the government can allow any agricultural land for non-agricultural purposes. He also questioned ‘Land Bank’ which he sees as the most recent plot to annihilate the Adivasi people.

Stan Swamy’s work an Oasis in the Desert

Because of Father Stan Swamy’s exceptional commitment to the most marginalised and vulnerable people, some of the news about atrocities and incidents of human rights violations in Jharkhand, a state otherwise largely ignored by mainstream media, started seeing the light of the day in the past two decades. His astounding documentation skills combined with his ability to network with other human rights groups ensured that there were several initiatives meant for the real development of a state like Jharkhand. He identified himself with Adivasi people and their struggle for a life of dignity. As a writer he expressed his critique of several of the government’s policies. Not only that, his silent and steady work with his humble and polite attitude made him dear to a lot of people he worked with. A group of activists that released a statement recently, said “Stan has been a vocal critic of the government’s attempts to amend land laws and the land acquisition act in Jharkhand, and a strong advocate of the Forest Rights Act, PESA and related laws. We know Stan as an exceptionally gentle, honest and public-spirited person. We have the highest regard for him and his work.”

Related Posts

The battle to protect Adivasis’ right to the land – A profile of Father Stan Swamy

FATHER STAN SWAMY

Fr. Stan Swamy is an indigenous people’s rights defender. He is the founder of Vistapan Virodhi Janvikash Andolan (VVJA), an all India platform for different movements that are campaigning against human rights violations caused by the displacement of Adivasis, Dalits, and farmers from their lands. The platform has supported vulnerable communities faced with displacement from extractive industry projects in securing their land rights and proposing sustainable development models instead. Swamy has also been involved in numerous fact-finding missions including putting together a report highlighting the illegal methods used by the government against Dalits and Adivasis.

According to the report ninety-seven percent of the 102 under- trials accused of being Maoists or “helpers of Maoists” when interviewed, reiterated that allegations against them were wrong. A large number of fake cases under the Unlawful Activities Prevention Act (UAPA) and stringent sections of the Indian Penal code were imposed upon Adivasis and Dalits without evidence. About 96% of the respondents earned less than Rs 5,000 a month—indicating low productivity of their landholdings. The study exposed the misuse of criminal justice procedures to repress the under trial detainees in the prisons. A large proportion of acquittals further corroborate the routine harassment that many innocent Adivasis are put through in the name of quashing “Maoism”.

Date of raids: 28 August 2018 and 12 June 2019

Charges: Father Stan Swamy’s house was raided in the morning on 28th August 2018. The police confiscated his laptop, mobile phone, and CDs. He was raided based on a fabricated connection to the Bhima Koregaon violence and his connection to Elgaar Parishaad. The police came to my house with something written in Marathi” and didn’t even bother to provide a copy of this FIR in which they named me,” Swamy said at a press conference, organised after the raids on Tuesday at his house in Bagaicha in Ranchi’s Namkum area to express support for those arrested and raided by teams of the Pune Police. “I neither have any connection with Elgar Parishad nor the violence that took place in Bhima Koregaon in January.” Dubbing the police action against eminent scholars and social activists a “naked dance of power”, Father Swamy said that while he personally knew Sudha Bharadwaj, Arun Ferreira and Vernon Gonsalves—who were among the activists whose homes were raided in connection with the Bhima Koregaon investigation—he has no connection with the others who were arrested. “Freedom of dissent is being suppressed by the government, which bodes ill for the future of the country,” he warned.

Update 12 October 2020: On 12 June 2019, an eight-member team of the Pune city police raided Father Stan Swamy in the early hours for the second time since August 2018. Swamy was questioned multiple times by the NIA at his residence in Bagaicha and according to him was interrogated for fifteen hours at a stretch. In the charge sheet, the agency has claimed that he is a CPI (Maoist) cadre and was actively involved in its activities. It was also claimed that he was in communication with other cadres and had received funds from them. The NIA also claimed that he was a convenor of the Persecuted Prisoners Solidarity Committee (PPSC), which it claimed was a frontal organization of CPI (Maoists). The NIA has also claimed that it had recovered incriminating documents, literature, and propaganda from him. Swamy has denied these charges , allegations of Maoist links, and said in the video that he recorded before his arrest has never been to Bhima Koregaon. In a statement, Swamy stated that the NIA placed several documents before him claiming they were taken from his computer implicating his connection to Maoists. “I told them all these were fabrications stealthily put into my computer and I disowned them.”

“I would just add that what is happening to me is not unique. Many activists, lawyers, writers, journalists, student leaders, poets, intellectuals, and others who stand for the rights of Adivasis, Dalits, and the marginalized and express their dissent to the ruling powers of the country are being targeted,” he said.

On 9 October 2020, Father stan Swamy was flown to Mumbai from Ranchi and produced before the court. The NIA did not seek his custody. Swamy was sent to judicial custody till 23 October in the middle of a global pandemic.

You can watch the video he recorded before his arrest here:

Location of work: Jharkhand

Fr. Stan Swamy: The Jharkhand Priest who made People his Religion by Sushmita

On the morning of August 28 just as the people of Ranchi city were waking up to a clear sky after heavy downpours in the previous days, and preparing themselves for the day’s chores, they were taken aback by the abrupt raid on the home of Father Stan Swamy, one of the city’s prominent social and political activists.

The Bagaicha campus, which is also the residence of Father Stan Swamy, was raided by the Maharashtra and Jharkhand police around 6 am and the search operations continued for several hours. The police confiscated Father Stan’s mobile, laptop, some audio cassettes, some CDs, and a recent press release on the Pathalgadi movement by Women against Sexual Violence and State repression (WSS). Father Stan was not told about the details of the charges against him. The police video-recorded the entire event.

This raid comes just a few weeks after Father Stan and 19 other persons including activists, journalists and intellectuals were booked on charges of sedition by the Jharkhand government. The police have cited their Facebook posts as evidence of their role in the Pathalgadi movement in Khunti. Among other sections, they have been booked under 66A of the Information Technology Act, 2000 which was repealed by the Supreme Court in 2015!

Rapid industrialization in Jharkhand

Ranchi, the capital city of Jharkhand, is a city with developmental aspirations. The landscape can be seen slowly transforming after it became the capital of the newly formed Jharkhand state in 2000. It accounts for more than 40% of the mineral resources of India, but it suffers widespread poverty as 39.1% of the population is below the poverty line and 19.6% of the children under five years of age are malnourished. The state is primarily rural, with only 24% of the population living in cities. The interests of Adivasis were never taken into account and the state saw several unstable and allegedly corrupt governments. But the exploitation of Adivasis especially increased after the BJP government came to power at the centre in 2014 and the aspirations of industrialization have seen an aggressive push by the state government since then. About 209 MoUs worth Rs. 3 lakh crores were signed last year itself, in an Investors Summit held in Ranchi in 2017. Rapid industrialization meant land had to be occupied and the rich minerals excavated from Jharkhand’s soil, by hook or crook, by legal or illegal mechanisms. It appears that force, rather than dialogue and negotiations has been given preference over everything with thousands of people displaced from their lands without adequate compensation or rehabilitation.

Owner of the land is also the owner of sub-soil mineral

The SC order that ‘Owner of the land is also the owner of sub-soil mineral’ [SC: Civil Appeal No 4549 of 2000] wherein the SC said that.We are of the opinion that there is nothing in”

the law which declares that all mineral wealth sub- soil rights vest in the State, on the other hand, the ownership of sub-soil/mineral wealth should normally follow the ownership of the land, unless the owner of the land is deprived of the same by some valid process”. Despite this, the rich land possessed by Adivasis have come under severe attack. And though the Supreme Court declared 214 out of the 219 coal blocks in the country illegal, ordering their closure and levying a fine, the Central and state governments allegedly re-allot the illegal mines through auction to make it look legal.

Father Stan Swamy’s extensive work

It is in this context that Father Stan Swamy has extensively worked in Jharkhand for the rights of the Adivasis. One of the major campaigns he was associated with was the Jharkhand Organisation Against Uranium Radiation (JOAR), a campaign against Uranium Corporation India Limited in 96. The campaign successfully stopped the construction of a tailing dam in Chaibasa which, if constructed, would lead to the displacement of adivasis in Jadugoda’s Chatikocha area. After vociferously raising these issues, he moved to work with the displaced people of Bukaro, Santhal Parganas and Koderma and has continued to work for them.

The plight of under-trials and fabricated arrests in Jharkhand

In 2010 he published a book titled, ‘Jail Mein Band Qaidiyon ka Sach’ exposing the arbitrary

and unlawful arrests of tribal youths with alleged links to the Naxal Movement. In his book, he highlighted that in 97% of the cases, the family income of the youths arrested was less than Rs. 5000 and they could not even afford lawyers to represent their cases. In 2014 when a report was published discussing the plight of the arrested youths, Father Stan came into the State machinery’s radar. According to the report 98% of the 3000 arrested were falsely implicated and had no links to the Naxal Movement. Some served years in jail without a trial. He has selfless contributed to pay for the youth’s bail bonds and approached lawyers to represent these cases in the court of law.

Uncomfortable questions

Father Stan Swamy was questioning the non- implementation of the Vth Schedule of the Constitution that stipulates that a ‘Tribes Advisory Council’ (TAC) composed solely of members from the Adivasi community should be constituted and it would advise the Governor of the State about the well being and development of the Adivasi communities. However, Father believed that despite seven decades since the Constitution came into force, none of the Governors (the discretionary heads of these councils) ever reached out to Adivasis to understand and work on their problems. Father also highlighted how Panchayats (Extension to Scheduled Areas) Act [PESA], 1996 was “neatly ignored” and “had deliberately been left unimplemented in all the nine states.” This Act, for the first time recognized the fact that the Adivasi communities in India have had a rich social and cultural tradition of self governance through the Gram Sabha. He tirelessly organised the adivasis to fight for the rights granted to them under (PESA). This transpired into the Pathalgadi movement in 2017. The Pathalgadi movement played an important role in highlighting the State’s methodical negligence to implement PESA. About the movement he said something very crucial: “As for the Pathalgadi issue, I have asked the question ‘Why are Adivasis doing this?’ I believe they have been exploited and oppressed beyond tolerance. The rich minerals which are excavated in their land have enriched outsider industrialists and businessmen and impoverished the Adivasi people to the extent there are starvation deaths taking place.”

Father Stan questioned the silence of the government on the Samatha Judgement 1997 of the Supreme Court which provided significant safeguards for the Adivasis to control the excavation of minerals in their lands and to help develop themselves. The judgment came at a time when consequent to the policy of globalization, liberalization, privatisation, national and international corporate houses started to invade particularly the Adivasi areas in central India to mine the mineral riches. Not only this, Father Stan questioned the lack of implementation of the Forest Rights Act (FRA) 2006. As per his findings, from 2006 to 2011, about 30 lakh applications were made under FRA all over the country for title-deeds, of which 11 lakhs were approved but 14 lakhs were rejected and five lakhs were pending. He also found out that the Jharkhand govt is trying to bypass the Gram Sabha in the process of acquiring forest land for industrial set up. More recently, he was questioning the recently enacted Amendment to “Land Acquisition Act 2013” by Jharkhand govt. Which he called as “death knell” for the Adivasis. He insisted that it did away with the requirement for “Social Impact Assessment” which was aimed at safeguarding the environment, social relations and cultural values of affected people. The most damaging factor, in his words, is that the government can allow any agricultural land for non-agricultural purposes. He also questioned ‘Land Bank’ which he sees as the most recent plot to annihilate the Adivasi people.

Stan Swamy’s work an Oasis in the Desert

Because of Father Stan Swamy’s exceptional commitment to the most marginalised and vulnerable people, some of the news about atrocities and incidents of human rights violations in Jharkhand, a state otherwise largely ignored by mainstream media, started seeing the light of the day in the past two decades. His astounding documentation skills combined with his ability to network with other human rights groups ensured that there were several initiatives meant for the real development of a state like Jharkhand. He identified himself with Adivasi people and their struggle for a life of dignity. As a writer he expressed his critique of several of the government’s policies. Not only that, his silent and steady work with his humble and polite attitude made him dear to a lot of people he worked with. A group of activists that released a statement recently, said “Stan has been a vocal critic of the government’s attempts to amend land laws and the land acquisition act in Jharkhand, and a strong advocate of the Forest Rights Act, PESA and related laws. We know Stan as an exceptionally gentle, honest and public-spirited person. We have the highest regard for him and his work.”

SUPPORT US

We like bringing the stories that don’t get told to you. For that, we need your support. However small, we would appreciate it.