Suddenly Stateless Conversation Series V: Procedure as Violence.

Suchitra Vijayan: Suraj, before we start, could you lay out to our listeners what the NRC is and what this process entails?

Suraj Gogoi: Sure, so the NRC was a document that was prepared in the state of Assam in 1951. It was meant to be a rough notebook that listed out names of people in Assam at that point in time, which certain enumerators carried out, but it was not meant to be used in any form. But later on, it became the basis of NRC Assam as we see in its current form. This process intended to identify “illegal immigrants” or illegal citizens or people within Assam. These so-called illegal people or citizens were primarily thought to be migrants from erstwhile East Bengal, today’s present-day Bangladesh. Now, NRC Assam took a long time to register—close to 60 million documents to identify whether one is legal or illegal, you know, people living in the state of Assam. This process also witnessed a lot of events in the last 2-3 years. The whole process was carried out in Assam… from 2015 onwards.

Right now, as it stands, we have about 1.9 million people or 19 lakh people, who are left out of this register, and their citizenship remains uncertain at this point. This NRC now becomes the basis for the National Population Register that the Indian state is planning to carry out in the entire Union of India. I suppose this sort of exercise will cause a lot of trauma and pain and cost heavily for people coming from the underclass, people who are poor. It’s often said that people who are poor are also document-poor, and NRC is an exercise that rests heavily on documents. In Assam, we had something called the Legacy Data, which originally comprised about 15 documents, which could be anything from your electoral rolls to land and tenancy records, citizenship certificates, refugee registration certificates, birth certificates, and educational documents from state or universities. In Assam, permanent residence certificates and bank records were a list of documents considered valid documents to prove one’s citizenship. There was a time frame which decided someone was a citizen of Assam. So, that time frame was from 1951 to the 24th of March 1971. So, this time frame is when all these documents would then be verified to locate whether your ancestors did belong to Assam or were part of Assam or India known as Legacy Data.

So, as you can see, there is a retrospective understanding of looking at a body or a citizen which is highly dependent on documents; now, no one imagined that such old documents would be of such value in the future, so much so that your entire existence, your civility and your political rights and economic rights will rest on these documents.

Q: Suraj, I quickly want to jump in and talk about the NRC process because I think you are already talking…going towards it… the process is not only something that is overwhelming, but the process is also deeply flawed and unconstitutional.

A: Sure…I mean to start with the NRC changes in legal terms the very basis of citizenship, which makes it very problematic and perhaps even unfair and illegal for many. So, in terms of changing the basic structure of the Constitution itself, strictly speaking in terms of how the idea of citizen is formulated or based on, it changes from jus soli to jus sanguinis. So, which means it carries a lot of implications. The first implication is that the proof of one’s identity or citizenship now solely rests on something called the Family Tree, which will be traced back to the different kinds of Legacy Documents I was talking about. That very basis when someone is supposed to prove one’s citizenship is not based on one’s birth. it’s rather based on one’s ethnic lineage or one’s family lineage. So, it’s no longer just based on the person. that is the first point of departure. So, even if someone is born in 1972 in Assam, it is not necessary that that person is a citizen. That’s the first, sort of, change.

Second, we can see India is shifting towards a very patrilineal understanding of citizenship in itself, where the family tree is the father’s Family Tree. It’s not the mother’s Family Tree. So, you see another point of departure here where earlier in jus soli, we see, you know, a person’s identity being the core of one’s citizenship. Now here, your own identity, your own being, becomes valueless unless you can prove and show that, you know, you belong to a family that carries some kind of documentation between these two years of 1951 and 1971.

Now, to get back to your specific query in terms of how it is unfair to a lot of people and how, perhaps in a way, one can also talk about the different biases of the NRC process. one has to consider the history of Assam, and if you talk about the political history of Assam, we do have to go back to the Assam Movement and even before…if not that far back, at least the Assam Movement. NRC in itself didn’t fall off from the sky. It was a certain desire of a certain section of people, and in this case, in Assam, it was the Assamese nationalists who wanted a certain kind of society, culture, and language to be embedded (within) its political boundary. And, so, this Assamese nationalism is at the core, which demanded something like NRC. there is a soul of NRC, and it is to be located in Assamese nationalism framed a very distinct idea of belonging of who belongs to Assam, who is an Assamese, who is not, who is an outsider, who is illegal. So, the whole history of Assamese nationalism defined the different measurements of culture, identity, and language as solely responsible for having NRC in the first place. So, if that is the case, then you see the different kinds of hatred towards the outsider, the stigma that is carried against the outsider, here, “Bangladeshi” and the Bangladeshi here in the majority are Muslim Bengalis. So, you see a kind of, you know, hate, a kind of gaze being constructed around this foreigner who finds through NRC a legitimate expression. This NRC, in a way, then legitimizes the kind of hatred, the kind of stigma that is present within Assamese nationalism. And this is the root of all evil. The philosophy of bias then gets legitimized through something like the NRC machine, which is operated by different levels of bureaucracy involved. At each level, we see a penetration of that kind of sentiment that these officers share. There are, of course, a lot of sympathizers to that kind of imagination of society, culture, and language. Someone from Barak Valley or Muslim Muslim-dominated districts goes and files an application for the NRC process or, say, appears before the judge in a Foreigners Tribunal — the moment you see and identify that one is a Bengali and one is a Muslim, there is a certain stigma already attached. This system then becomes automatically a machine that differentiates people and distinguishes people.

Now, oftentimes, we hear people who support NRC say that NRC is a Supreme Court-mandated process. Yes, it is a Supreme Court-mandated process, but that does not take away the fact that it is a legitimate expression of Assamese nationalism, which is biased towards a certain section of people, and that remains. I think that is very crucial in terms of how we frame, understand, or even explain the bias that is inherent in the NRC process.

Q: Suraj, one of the arguments that is consistently being made within the Assamese academic and scholarly circles is this idea that there is an inherent difference between mainland scholarship and Assamese scholarship and that somehow mainland scholarship, while talks about Assamese nationalism, even ethnonationalism, refuses to understand the genuine fear of the Assamese people and the fear of erasure of their identity and history and politics. What do you make of that strain of argument? Can you lay that out for us?

A: Right…no, that is a very pertinent concern that sympathizers of Assamese nationalism share and I personally stand against this binary, and I don’t think that there is any rational and reasonable basis on which these arguments are made. Let me try to show how Assamese intellectual discourse’s whole assertion and complaint points to that sort of argument.

To start with, we often come across a very typical argument that people accuse us, generally all academics, that you are not grounded enough; your data doesn’t speak of ground realities. I believe that kind of an argument that if we are saying that you are being xenophobic, you are chauvinistic, then they would respond by saying that, no, you don’t understand us, and there is this often quoted statement that you don’t understand our emotions, you don’t understand our grounds. Now I feel that is a very lazy kind of assertion.

One, to start with, they resort to something called settler colonialism. The subject of this argument is the so-called Bengali peasants who settled in different parts of the Brahmaputra valley in the early decades of the 20th century. And this didn’t happen, you know, it didn’t happen in a decade. The migration pattern is spread out. Now, the Assamese nationalists often suggest that these people are settler colonialists. Now, the very premise of settler colonialism assumes or rather presupposes two things, if not more: that they are powerful – the settlers, and they come with the intent of capturing the land, and they assert their independence or sovereignty in those lands. secondly, in terms of settler colonialism, one of the other presuppositions is that it is not an event. It’s more of a structural issue here when discussing settler colonialism. And along with sovereignty, they want to assert control of the land.

Now, if you look at the kind of settlements that took place in Assam, strictly speaking in terms of Bengali peasants, it was neither. They have never asserted sovereignty nor tried to own legal control over the lands they cultivate and get by with different productive activities. And these people who migrated, if you look at their profile – they were the social underclass, and they migrated from erstwhile East Bengal, which was then part of India, for various reasons. At that point, Bengal had the Zamindari System, and Assam had a different kind of land regulation, which was thought to be less exploitative. There was also a lot of political interest in settling these people or, rather, allowing them to settle in the Brahmaputra valley. But, at the same time, these were poor and landless peasants. So, they certainly didn’t have any power in terms of their assertion on land or political assertions of other kinds.

Now, if you look into the area of their settlement, which are in Assamese known as Char Chaporis or these are riverine areas in the Brahmaputra Valley. if you look into the composition of these areas, they are constantly flooded areas, and they keep shifting and changing with every flood. The Brahmaputra is a river that is known for its floods multiple times a year. Now these areas, most of these areas have never been surveyed by the government. No revenue survey is done on these areas, meaning there are no land documents for these areas. So, how can settler colonialism function when there are no land documents of most of these places where these so-called settlers settled or cultivated and got by? So, this is one of the first myths Assamese intelligentsia tried to build over time, and this is not just the current intellectual discourse that we find. This embedding of a kind of a myth was seen by historians who were writing, you know, trying to re-write Assamese history through the lens of the Ahom history from the early decades of the 20th century.

Now, that sort of intellectual tradition is inherited by a lot of people and a lot of writers that we find in Assam today. For me, they have been very dishonest with the kind of history and the organization or the configuration of society we find in Assam. This dishonesty is also seen in terms of how they blur and romanticize one’s identity, of the indigenous. Romanticism, for me, as many authors have pointed out, is also when someone ignores the internal differences and internal hierarchies that exist in our society. Now, it is written in almost all kinds of critical writings on Assam, be it history, in political science, or sociology. One of the main characteristics of Assamese identity is that it is highly driven by a particular middle class who are of upper caste. So often, you see this statement – caste Assamese middle class.

Now, that identity is being preserved and also hidden by this intellectual class in asserting a certain kind of indigenous identity…a kind of ‘son of the soil’ identity where they tried to glorify a kind of society that we find here in terms of the indigenous, where all other forms of diversities that make up Assamese political, cultural landscape gets erased in the process. At the same time, the domination of a particular class and caste of people within Assam remains, which this intellectual class have tried very hard to hide.

And, yes, I mean, there is no denying that there is this whole argument about how mainland India or the mainland gaze of a large section of literature or society on the East remains problematic, and there is no denying that. How even the Indian state has treated the region also remains deeply problematic and divided, and people like Bimol Akoijam and Prasenjit Biswas have written about this ‘exceptionality’ of North Eastern India. But, at the same time, while we remain critical of the gaze of the Indian state and the “mainland” about the region, the racial gaze portrayed on the region should remain a point of critical enquiry and criticism. But at the same time, this dishonesty of the intellectual class in hiding their own domination and hegemony and presenting a very sanitized history remains problematic. I think, which is where this whole conflict between the son of the soil or Assamese nationalists vis-à-vis the so-called, you know, Delhi-based voices collide.

Q: Can we quickly move into this idea of procedural and institutional violence that you have talked about and written quite extensively about? I was wondering if you could walk us through that, that institutional violence and procedural violence but also in relationship the detention camps that are coming…that have already come up in Assam…

A: Right, right…so you mean procedural violence just strictly in terms of the NRC?

Q: Yes, the NRC, but also the detention because, correct me if I am wrong, the NRC is not just NRC, but we also have the process in which you have a vast number of people who are now being detained in these various detention camps. So, I was wondering if you could make the connection for us but also ground this idea of procedural and institutional violence in the background.

A: Sure. So, a couple of institutions are crucial for the NRC process for its functioning. One is the Foreigner’s Tribunal, the other is the institution of Border Police, and then, of course, you have the main NRC itself and the detention centres or sort of, like jails where these detained people are kept. If we talk about procedural violence, I think all these four institutions become crucial in terms of understanding how an illegal body is identified.

I think the first kind of violence is to be located in terms of forcing people to prove their citizenship. I think that is the first instance of violence. It is the first instance because one is made to undergo a whole lot of paperwork on their own, and there is no support of any kind until the state came up with a list of guidelines after the final list was published on 31st August last year, saying that they will provide legal aid. But, before that, people were on their own, and of course, there were a lot of illiterate people. This is a rather cumbersome process, and this whole process of documents will certainly require a lot of help from people. Forget about finding the document, just the file, and you know, to come and submit itself is an uphill task. Now, if there is a mistake in the document, you get notified. That correction procedure takes another whole lot of journey. So, in one such instance, when you are being notified by the Foreigner’s Tribunal, there’s a hearing of your case, and people are made to travel almost 400-500 kilometres on a notice period of 24 hours or 48 hours. And, I think, last year there were a couple of road accidents of people travelling to present themselves in these cases. And I think close to 68000 ex-parte judgements being made where these people were declared foreigners when they were not even there to defend themselves. So, I think that kind of impatience on the part of the state signals a lot within the system, but, at the same time, people have been thrown everywhere to just run around for a piece of paper to prove their identity.

The other thing related to that is violence in terms of how people are deeply affected by it psychologically and the number of suicides that have taken place in the past 2-3 years in Assam. People are being made to undergo so much pain that they have decided to kill themselves. These are hard, physical evidence of trauma and anxiety, but I am sure many more are deeply troubled. If you look into the cases of suicides, you know there are different kinds. It’s not only people who are victims of the NRC process, meaning those who are not able to prove their identity and were declared foreigners or were in an uncertain limbo, sort of a phase, and they decided to kill themselves.

I think the third kind of violation is people who are detained and kept in detention centres, as you pointed out. They are being subjected to more than inhuman treatment in these centres, and there is no aid of any kind, and they have been kept away from their families, from their kids. I think there were a couple of cases where both the newborn and the mother had to be in detention, kept away from family. And so far, if I am not mistaken, there have been 25 cases of death in detention…

Q: We have been following that, and I think right now the number of deaths in detention is 31, if I am not mistaken…

A: I See. Okay.

I guess…I mean, these cases have only increased over time, and I think there were families who refused to receive the dead bodies in a couple of cases. In at least three cases they won’t receive their family member because they were declared as a Bangladeshi or a foreigner, and unless and until they declare them as Indian, they won’t accept their bodies. And I think in one case, two ministers from the state ensured that they would do everything to handle the case and see that the person was declared as Indian and only then the family accepted the body.

So, this kind of posthumous citizenship is not something new, and it can go a long way in healing the pain of these victims and their families. Israel, in 1985, gave posthumous citizenship to all 6 million Jews, and there are lots of cases of posthumous citizenship being granted to undocumented soldiers who either suffer death or any kind of serious injuries in war in America. So, we can certainly sort of talk about the possibilities of posthumous citizenship, at least in the context of NRC, where these people are severely undergoing different kinds of trauma.

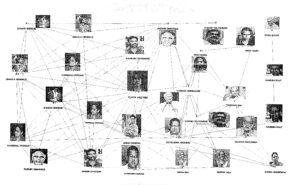

So, this procedural violence can then be located through these different institutions, which refuse to hear the pain of these people and have remained very problematic. I have come across a case where this person defended his case seven times in the foreigner’s tribunal, and each time, he could prove he was not illegal. So, these cases keep bouncing back, and there is no accountability whatsoever, and people are made to run pillar to post and spend so much money. I think the kind of expenditure made just to become a citizen in Assam is mind-blowing. This image is of a Muslim man trying to dry his papers in a flood relief camp in Bodoland. And that image was very gripping because oftentimes you see people leaving their homes, trying to guard their cattle and their grain and maybe some other valuable things to go and stay in the relief camp till the flood water recedes. But in this case, there is no such thing. This person was grabbing onto the documents and was sort of laying it out in the open to dry. I think this speaks a lot of volumes about how people are reduced to these documents as if there is nothing more to life than proving one’s identity. What can that sort of a mentality suggest, in terms of one’s urge or one’s love to belong to a particular place, than to, you know, to suffer in terms of how these papers have taken over their lives? I think that’s proof of a kind of nationalism. That is the highest proof that one can have regarding a citizen and how they relate to a place.

Q: But it is also a kind of deep fear of annihilation, correct?

A: Yes.

Q: That, it’s very interesting that you brought up this document because 2-3 years ago, when I was in Assam, travelling. This was before the NRC had happened. I was going to a village to interview someone and …The monsoon had just happened, and a very similar image where the family of the woman I was going to interview, you know, had just again taken these things out, and she was just drying everything. She was drying old ID cards because she was very worried that, you know, the thing would happen…what does the NRC exercise, in your opinion and of course the recent Citizenship Amendment Act mean for the ideas of citizenship?

Also, you very eloquently talk about this as the highest form of nationalism. For me, it is also a point where…for many in India now, this is also a point of absolute annihilation—absolutely manufacturing a class of undocumented class of stateless people. So talk to us about this idea of citizenship after NRC, after the Citizenship Amendment Act.

A: Right. I mean, I think it’s kind of an irony. It’s often said that South Asia is the graveyard of social theory, where all kinds of analysis fall apart. But it now appears that Assam is the graveyard of Indian citizenship and democracy. Now, I suppose there are a lot of implications as we can already see that I have tried also to put it out that there is a very organic link between NRC and CAA or CAB earlier because the Citizenship Amendment Bill (CAB) 2016 was primarily introduced to accommodate the Hindu “Bangladeshis” who could have been left out of the NRC process. So, you can see that CAB’s main intention was to accommodate these people who belong to a particular religious group within the so-called illegal citizens, illegal people. Now, if you look at that organic link, you can see how the NRC becomes the main point from which everything gets pulled out.

Now, the Indian state wants to conduct an all-India NRC, but right now, they are calling it NPR. They are trying to push this idea that this is not NRC. But there are a lot of similarities if we go back to the 1951 NRC with the NPR, which is just a documentation of people in various districts in India. So, this will seem as if, it is a census-like document, but then this will become the basis of a full-fledged NRC at some point.

Now, if I may digress a little bit before I come to your question, here I am just speculating why 1951 became the base year for NRC; why not any other year? And I started looking for reasons because you can see a lot of assertions being made by different kinds of actors and institutions even to push the Assam NRC date to 1826 when, you know, the Treaty of Yandabo was signed, and formally British came into the North East. So, why not, say, for instance, 1901 or 1921? I think the rationale for 1951 NRC is not in 1951 NRC, but 1951 becomes a date for a base year rather for NRC, and the rationale is to be found in the Census of India — the way you know, the census changed in India.

So, there is a very interesting study by the scholar in JNU who wrote this dissertation in 1977 – Neelufar Ahmed. Ahmed talks about the problems of the census data. And the study by Ahmed was conducted between 1891-1931. Now, there are a couple of problems. To start with, back then, districts were the smallest unit of measure in the census, and districts were quite huge at that point in time. There were only ten districts in Assam in 1891, which has now grown. The second problem then associated with the bigger districts had to do with how many states were carved out of Assam–Meghalaya and a couple of other states. So, lot of shifting of boundaries and districts – not only district boundaries but also state boundaries took place. The third problem, Ahmed points out, is that only in-migration could be documented. So, the place of birth of a person was never documented in the census earlier on, so out-migration is not possible to be located within this data. The fourth problem associated with the census till 1931 is that…also the motive of the migrant was not listed. Now, these four things combined pose a problem. So, until 1931, these problems remained, and I think this is extremely crucial in understanding why the year cannot be pushed beyond 1951. And now there is an associated problem along with this problem. The other crucial thing to note here is that the nature of the census also underwent a change. For the first time in 1941, we see that the census started sort of also documenting certain changes within these four things I spoke about. So, there was a lot of reorganization within the state, and also, the kind of migration flows were increasing into Assam.

Earlier, you know, a lot of migrants were mostly settling in places like Goalpara 48:08-48:10 unclear district and its adjoining areas but changed later on. It’s very interesting to note that a term like ‘invasion’ was used not to designate migrants coming outside the state but was used rather to designate migration within districts. So, you see how this sort of outlook changes. Or rather, this outlook of…which is usually now attached to so-called illegal migrants, was not really to designate with that intent. It was not used with that intent in the census, but then it became something else. it is not possible to push beyond 1951 precisely because, prior to 1931, you cannot tell who migrated from where. So, that is precisely one of the reasons why 1951 became the base year because in 1941…again, there is a problem because of war. The census remained incomplete in India. So, the data, the kind of data that is required, is not available throughout India, and most likely, it also did affect Assam in many ways.

So, I think, again, I am saying this is mere speculation on my part here to look at why one is unable to push the base year beyond 1951. But then, I think this carries a lot of implications in terms of nationwide NRC. Now, if 1951 is the base for Assam, then what will be the base for India or if at all, there will be a sort of time-frame given for the rest of India like it was in the case of Assam between 51 and 71?

So, what remains crucial is that this becomes like our ex-Chief Justice pointed out that NRC is a future document. So, this becomes a referent in a way for future NRC on an all-India scale. And I think this again for me is very problematic, and like you said, we are sort of underwriting our own annihilation in the process, and whether we participate in this process or not is a different thing. that whole poem that goes around – kaghaz nahi dikhayenge but I think not to be able to show, I mean that itself carries a lot of weight. To not show…

Q: And privilege of caste and class…

A: Yes, exactly. To not show implies that you have the document, whereas there are large sections of people who do not have it and that in no way suggests that they are illegal or it is just that we have migrated so much. Our entire labour class, the social underclass that we find in cities in India, have migrated from different rural areas in India and like Ashish Nandy puts it, in these ambiguous journeys people have made, there was no culture of preserving documents, and we were never told that after 7-8 decades of independence, one will be asked to prove ones belonging which is preposterous. I think this is the pinnacle of humiliation one can undergo –to be told to prove that you don’t or rather told that you don’t belong here after having lived for so many years.

Q: Also, the basis that all those residing within the territorial borders of India are assumed illegal before proof also goes against the fundamentals of a “secular constitution”. Having said that, I very quickly want to go on to this idea again of characterizing the NRC as… a very exceptional or a totalitarian nightmare, but in reality, it is neither exceptional nor totalitarian but something that is procedural violence with a having a long history. Can you speak to us about this nature of unexceptional but ongoing violence that is the NRC and how institutional bodies have inflicted this on the people of Assam and now throughout India?

A: Right. So, let me start with an example from my hometown, Sadiya, in the easternmost part of Assam. During my doctoral fieldwork, I have encountered a couple of families who are currently Muslims. They write usual titles like Ali, Khan, and so on and so forth. And then, I have also met a set of people, a couple of families, who write typical “Assamese” surnames like Dutta, Baruah and others. Now, during the NRC verification process, it has come to light that their ancestors who were living in Sadiya belong to opposite religions. The people who are now Muslims were caste Assamese, and the people who aren’t, who are Assamese right now, were actually Muslim Bengalis. Now, these people, particularly the ones who are Assamese and were Muslims earlier on, have come to face a lot of, if not ostracization, but avoidance from a lot of people knowing that they were Muslims.

Now, you see, I would say NRC has opened up these unnecessary wounds. This very fact of people having to change their cultural identity, even religious identity in Assam, in the face of different kinds of nationalistic oppositions from different actors was highlighted by a lot of commentators and reporters back in the days of the Assam Movement, and one of them is the very brave, Nirupama Borgohain who also suffered a lot at the hands of the nationalists. She pointed out during her report that many Bengali families who converted to Assamese have given up their language and culture to remain safe. Does this sound very familiar to the kind of fascist onslaught we see or hear, say from Gujrat or even UP? This, I think, is an extremely problematic and deeply traumatizing development or rather a history and something very similar if not changing or acquiring different cultural and religious domains.

A lot of research also has shown how there was an increase in ghettoization of people in UP after Ayodhya, which wasn’t so apparent before Ayodhya. So, something very similar is happening here, and of course it’s not replicated in this same manner, but the history of Assamese nationalism shows that this kind of animosity between different groups, religious, cultural and linguistic, has led to very traumatic experiences for the minorities in the state. Oftentimes, if we speak about the Nellie Massacre in Assam where thousands of people, I mean, the official numbers say stands at 2000, but I think the unofficial count goes up to a few more thousands were killed not with guns but with knives and other kinds of spears. And this happened at the peak hour of the Assam Movement, and who is responsible for this? And of course, all the leaders, including Prafulla Kumar Mahanta and the Assam Sahitya Sabha – the cultural, literary body in Assam and all others tried to absolve themselves of this whole heinous act of murder and annihilation of people and these people who were targeted belong to a particular community, and there is no denying that this kind of wounds will certainly be opened up and this whole NRC process has sort of antagonized a lot of people and also woken up and a lot of this kind of ethno-nationalist sentiments and particularly with the…Citizenship Amendment Act protest, we see in Assam, it’s deeply disturbing for many of us and for people here and they often say that the protest in North East or Assam is very different from rest of India. But before we go into that, one can, I mean, one should really look into the nature of protest that is happening in the East, and it fascinates me.

I have been to a couple of them to see public protests and how they are being organized, and what I saw was deeply tumblehome. I mean, it was worrying to see how as if hate has become respectable in our society and hate for the outsider was sold out like commodities by these artists in Assam. And I think with the CAA protest, a whole new generation of students, particularly students and the younger generation in Assam and North East, is being baptized by the same kind of leadership, the same kind of regressive leadership that led the Assam Movement. The new generation is being baptized with the same kind of politics, to hate the outsider, and this is deeply problematic.

And even if you look into the aesthetics of the protests here, it’s so powerful. There are a lot of videos shared where young students from schools and colleges…undergrad colleges, were cutting their own arms, and with the blood, they were writing different anti-CAA posters into papers, into the gamacha – the cloth that you see with red borders and white background. And this invocation of blood and soil is very powerful and problematic at the same time. It remains very problematic in terms of the kind of discourse it appeals to, and that discourse is definitely one of martyrdom, and that martyr discourse then easily slips into the discourse of violence.

Often times you hear that the protest is different from mainland India and how it is organized here. They tend to say that we are very secular here. In a sense, they are saying that we don’t want both Muslims and Hindus, and that’s why we are secular. I think this is the very limited understanding of what is secular and what is communal. I mean, the understanding of secular is not only premised on religious grounds, but such an outlook for me lacks an appreciation of cultural diversity, history and a whole lot of things.

Q: I just want to finish our podcast with one last question. There have been a lot of complaints from Assam, especially from a generation of young scholars and activists saying how mainstream India does not document or report on these protests properly. For example, there has been immense violence on the protesters; there has been an imposition of curfew, you know, five protesters have been shot dead in Assam, there is teargas, there is a lathi charge, and of course, activist Akhil Gogoi has been arrested. It also puts one in this position where one is trying to understand, as you rightly talked about how you can’t have, you can’t say you are secular and say we don’t want either Muslims or Hindus, you know, but I was kind of wondering what your take on this was that do you feel that there is a protest movement that is happening that can actually be one that is not baptized by hate. Does that possibility still exist? What do you think about that, or do you think all of these protests are so now colored by a certain sense of Assamese nationalism?

A: Right. I mean, as far as I have seen, I haven’t seen anything but hate and this kind of coloring that you talk about, it’s far too powerful, and that is the dominant discourse. We are forever trapped in that discourse of the Assam Movement, and a new set of people are now followers of that discourse. And to give you an example, the artist society has come out and is leading the protest in Assam. One of the usual slogans used in protests, if I may roughly translate, it says — ‘O come out! Please, everyone, come out! Let’s chase the Bangladeshi!’ This keeps on reverberating and being used everywhere. These are some of the lyrics of the song, and there is much more problematic stuff in it. So, this kind of discourse is so powerful and sediments the kind of hate for the outsider and, here in this case, the “Bangladeshi”. I don’t see, as of now, any kind of protest outside this discourse, and this is also not to say that there isn’t a possibility outside this discourse. I mean, I do have hope or rather, I do say that there is a possibility beyond this dominant and ethno-nationalist discourse because there we have had a lot of intellectuals in the 40s and 50s who tried to appeal to people and did write different kinds of material, be it songs, be it music, be it plays, and so on and so forth, which spoke of a multilingual, multicultural Assam and in their articulations and here, I am referring to people like Jyoti Prasad Agarwala, Bishnu Rabha who did accommodate everyone to talk about cultural identity, talk about a linguistic identity of people and in their articulations we find, a celebration of the beautiful, celebration of a culture which is invested in beauty. And I think that sort of cultural philosophy one needs to really critically engage with, and I think the possibilities can come from people such as them who are also considered as cultural icons in Assam, but the way they are being used or rather appropriated creates a sensation of ethnonationalism and sanitizes the kind of multicultural accommodative politics they spoke of.

And to your last point about misreporting and underreporting, I think that is true to a large extent, and I would also like to add that underreporting is not just in the case of protests but it is a general sort of practice or experience and this underrepresentation is not just in terms of media but also in terms of intellectual practice that we find, the kinds of history that are written. How the histories of people, culture, society and language of North East never find mention in any curriculum in schools in India and even if they do, it’s perhaps very recent or just in passing.

So, these problems are more structural. They are inherent not just in terms of how the media reports them but also, I think, are present in different ways, which brings about a kind of lacuna and problem in understanding and explaining the whole region of the East.

And lastly, I think what I have sort of tried to highlight in my writings is that, yes, we do need to be critical about how we are being looked at or understood, written about by people from outside, but at the same time, it’s also very cynical and childish even to assume that someone who does not belong to North East cannot understand the concerns and commitments of people here. And at the same time, we need to be critical about our culture and society and how we look at the minorities in Assam or in North East, and I am not talking about minorities in terms of who is seen as a “foreigner”, but I am also talking about minorities in terms of different tribal groups, different indigenous groups who are not in that power structure, who do not command that kind of power in different states in North East. I think the focus is very, very necessary and not just a complaint on the part of how we are being thought of, imagined and are written from the outside but that internal differences and distinctions are also very necessary to be highlighted if we do think of critical scholarship in the future.

Related Posts

Suchitra Vijayan: Suraj, before we start, could you lay out to our listeners what the NRC is and what this process entails?

Suraj Gogoi: Sure, so the NRC was a document that was prepared in the state of Assam in 1951. It was meant to be a rough notebook that listed out names of people in Assam at that point in time, which certain enumerators carried out, but it was not meant to be used in any form. But later on, it became the basis of NRC Assam as we see in its current form. This process intended to identify “illegal immigrants” or illegal citizens or people within Assam. These so-called illegal people or citizens were primarily thought to be migrants from erstwhile East Bengal, today’s present-day Bangladesh. Now, NRC Assam took a long time to register—close to 60 million documents to identify whether one is legal or illegal, you know, people living in the state of Assam. This process also witnessed a lot of events in the last 2-3 years. The whole process was carried out in Assam… from 2015 onwards.

Right now, as it stands, we have about 1.9 million people or 19 lakh people, who are left out of this register, and their citizenship remains uncertain at this point. This NRC now becomes the basis for the National Population Register that the Indian state is planning to carry out in the entire Union of India. I suppose this sort of exercise will cause a lot of trauma and pain and cost heavily for people coming from the underclass, people who are poor. It’s often said that people who are poor are also document-poor, and NRC is an exercise that rests heavily on documents. In Assam, we had something called the Legacy Data, which originally comprised about 15 documents, which could be anything from your electoral rolls to land and tenancy records, citizenship certificates, refugee registration certificates, birth certificates, and educational documents from state or universities. In Assam, permanent residence certificates and bank records were a list of documents considered valid documents to prove one’s citizenship. There was a time frame which decided someone was a citizen of Assam. So, that time frame was from 1951 to the 24th of March 1971. So, this time frame is when all these documents would then be verified to locate whether your ancestors did belong to Assam or were part of Assam or India known as Legacy Data.

So, as you can see, there is a retrospective understanding of looking at a body or a citizen which is highly dependent on documents; now, no one imagined that such old documents would be of such value in the future, so much so that your entire existence, your civility and your political rights and economic rights will rest on these documents.

Q: Suraj, I quickly want to jump in and talk about the NRC process because I think you are already talking…going towards it… the process is not only something that is overwhelming, but the process is also deeply flawed and unconstitutional.

A: Sure…I mean to start with the NRC changes in legal terms the very basis of citizenship, which makes it very problematic and perhaps even unfair and illegal for many. So, in terms of changing the basic structure of the Constitution itself, strictly speaking in terms of how the idea of citizen is formulated or based on, it changes from jus soli to jus sanguinis. So, which means it carries a lot of implications. The first implication is that the proof of one’s identity or citizenship now solely rests on something called the Family Tree, which will be traced back to the different kinds of Legacy Documents I was talking about. That very basis when someone is supposed to prove one’s citizenship is not based on one’s birth. it’s rather based on one’s ethnic lineage or one’s family lineage. So, it’s no longer just based on the person. that is the first point of departure. So, even if someone is born in 1972 in Assam, it is not necessary that that person is a citizen. That’s the first, sort of, change.

Second, we can see India is shifting towards a very patrilineal understanding of citizenship in itself, where the family tree is the father’s Family Tree. It’s not the mother’s Family Tree. So, you see another point of departure here where earlier in jus soli, we see, you know, a person’s identity being the core of one’s citizenship. Now here, your own identity, your own being, becomes valueless unless you can prove and show that, you know, you belong to a family that carries some kind of documentation between these two years of 1951 and 1971.

Now, to get back to your specific query in terms of how it is unfair to a lot of people and how, perhaps in a way, one can also talk about the different biases of the NRC process. one has to consider the history of Assam, and if you talk about the political history of Assam, we do have to go back to the Assam Movement and even before…if not that far back, at least the Assam Movement. NRC in itself didn’t fall off from the sky. It was a certain desire of a certain section of people, and in this case, in Assam, it was the Assamese nationalists who wanted a certain kind of society, culture, and language to be embedded (within) its political boundary. And, so, this Assamese nationalism is at the core, which demanded something like NRC. there is a soul of NRC, and it is to be located in Assamese nationalism framed a very distinct idea of belonging of who belongs to Assam, who is an Assamese, who is not, who is an outsider, who is illegal. So, the whole history of Assamese nationalism defined the different measurements of culture, identity, and language as solely responsible for having NRC in the first place. So, if that is the case, then you see the different kinds of hatred towards the outsider, the stigma that is carried against the outsider, here, “Bangladeshi” and the Bangladeshi here in the majority are Muslim Bengalis. So, you see a kind of, you know, hate, a kind of gaze being constructed around this foreigner who finds through NRC a legitimate expression. This NRC, in a way, then legitimizes the kind of hatred, the kind of stigma that is present within Assamese nationalism. And this is the root of all evil. The philosophy of bias then gets legitimized through something like the NRC machine, which is operated by different levels of bureaucracy involved. At each level, we see a penetration of that kind of sentiment that these officers share. There are, of course, a lot of sympathizers to that kind of imagination of society, culture, and language. Someone from Barak Valley or Muslim Muslim-dominated districts goes and files an application for the NRC process or, say, appears before the judge in a Foreigners Tribunal — the moment you see and identify that one is a Bengali and one is a Muslim, there is a certain stigma already attached. This system then becomes automatically a machine that differentiates people and distinguishes people.

Now, oftentimes, we hear people who support NRC say that NRC is a Supreme Court-mandated process. Yes, it is a Supreme Court-mandated process, but that does not take away the fact that it is a legitimate expression of Assamese nationalism, which is biased towards a certain section of people, and that remains. I think that is very crucial in terms of how we frame, understand, or even explain the bias that is inherent in the NRC process.

Q: Suraj, one of the arguments that is consistently being made within the Assamese academic and scholarly circles is this idea that there is an inherent difference between mainland scholarship and Assamese scholarship and that somehow mainland scholarship, while talks about Assamese nationalism, even ethnonationalism, refuses to understand the genuine fear of the Assamese people and the fear of erasure of their identity and history and politics. What do you make of that strain of argument? Can you lay that out for us?

A: Right…no, that is a very pertinent concern that sympathizers of Assamese nationalism share and I personally stand against this binary, and I don’t think that there is any rational and reasonable basis on which these arguments are made. Let me try to show how Assamese intellectual discourse’s whole assertion and complaint points to that sort of argument.

To start with, we often come across a very typical argument that people accuse us, generally all academics, that you are not grounded enough; your data doesn’t speak of ground realities. I believe that kind of an argument that if we are saying that you are being xenophobic, you are chauvinistic, then they would respond by saying that, no, you don’t understand us, and there is this often quoted statement that you don’t understand our emotions, you don’t understand our grounds. Now I feel that is a very lazy kind of assertion.

One, to start with, they resort to something called settler colonialism. The subject of this argument is the so-called Bengali peasants who settled in different parts of the Brahmaputra valley in the early decades of the 20th century. And this didn’t happen, you know, it didn’t happen in a decade. The migration pattern is spread out. Now, the Assamese nationalists often suggest that these people are settler colonialists. Now, the very premise of settler colonialism assumes or rather presupposes two things, if not more: that they are powerful – the settlers, and they come with the intent of capturing the land, and they assert their independence or sovereignty in those lands. secondly, in terms of settler colonialism, one of the other presuppositions is that it is not an event. It’s more of a structural issue here when discussing settler colonialism. And along with sovereignty, they want to assert control of the land.

Now, if you look at the kind of settlements that took place in Assam, strictly speaking in terms of Bengali peasants, it was neither. They have never asserted sovereignty nor tried to own legal control over the lands they cultivate and get by with different productive activities. And these people who migrated, if you look at their profile – they were the social underclass, and they migrated from erstwhile East Bengal, which was then part of India, for various reasons. At that point, Bengal had the Zamindari System, and Assam had a different kind of land regulation, which was thought to be less exploitative. There was also a lot of political interest in settling these people or, rather, allowing them to settle in the Brahmaputra valley. But, at the same time, these were poor and landless peasants. So, they certainly didn’t have any power in terms of their assertion on land or political assertions of other kinds.

Now, if you look into the area of their settlement, which are in Assamese known as Char Chaporis or these are riverine areas in the Brahmaputra Valley. if you look into the composition of these areas, they are constantly flooded areas, and they keep shifting and changing with every flood. The Brahmaputra is a river that is known for its floods multiple times a year. Now these areas, most of these areas have never been surveyed by the government. No revenue survey is done on these areas, meaning there are no land documents for these areas. So, how can settler colonialism function when there are no land documents of most of these places where these so-called settlers settled or cultivated and got by? So, this is one of the first myths Assamese intelligentsia tried to build over time, and this is not just the current intellectual discourse that we find. This embedding of a kind of a myth was seen by historians who were writing, you know, trying to re-write Assamese history through the lens of the Ahom history from the early decades of the 20th century.

Now, that sort of intellectual tradition is inherited by a lot of people and a lot of writers that we find in Assam today. For me, they have been very dishonest with the kind of history and the organization or the configuration of society we find in Assam. This dishonesty is also seen in terms of how they blur and romanticize one’s identity, of the indigenous. Romanticism, for me, as many authors have pointed out, is also when someone ignores the internal differences and internal hierarchies that exist in our society. Now, it is written in almost all kinds of critical writings on Assam, be it history, in political science, or sociology. One of the main characteristics of Assamese identity is that it is highly driven by a particular middle class who are of upper caste. So often, you see this statement – caste Assamese middle class.

Now, that identity is being preserved and also hidden by this intellectual class in asserting a certain kind of indigenous identity…a kind of ‘son of the soil’ identity where they tried to glorify a kind of society that we find here in terms of the indigenous, where all other forms of diversities that make up Assamese political, cultural landscape gets erased in the process. At the same time, the domination of a particular class and caste of people within Assam remains, which this intellectual class have tried very hard to hide.

And, yes, I mean, there is no denying that there is this whole argument about how mainland India or the mainland gaze of a large section of literature or society on the East remains problematic, and there is no denying that. How even the Indian state has treated the region also remains deeply problematic and divided, and people like Bimol Akoijam and Prasenjit Biswas have written about this ‘exceptionality’ of North Eastern India. But, at the same time, while we remain critical of the gaze of the Indian state and the “mainland” about the region, the racial gaze portrayed on the region should remain a point of critical enquiry and criticism. But at the same time, this dishonesty of the intellectual class in hiding their own domination and hegemony and presenting a very sanitized history remains problematic. I think, which is where this whole conflict between the son of the soil or Assamese nationalists vis-à-vis the so-called, you know, Delhi-based voices collide.

Q: Can we quickly move into this idea of procedural and institutional violence that you have talked about and written quite extensively about? I was wondering if you could walk us through that, that institutional violence and procedural violence but also in relationship the detention camps that are coming…that have already come up in Assam…

A: Right, right…so you mean procedural violence just strictly in terms of the NRC?

Q: Yes, the NRC, but also the detention because, correct me if I am wrong, the NRC is not just NRC, but we also have the process in which you have a vast number of people who are now being detained in these various detention camps. So, I was wondering if you could make the connection for us but also ground this idea of procedural and institutional violence in the background.

A: Sure. So, a couple of institutions are crucial for the NRC process for its functioning. One is the Foreigner’s Tribunal, the other is the institution of Border Police, and then, of course, you have the main NRC itself and the detention centres or sort of, like jails where these detained people are kept. If we talk about procedural violence, I think all these four institutions become crucial in terms of understanding how an illegal body is identified.

I think the first kind of violence is to be located in terms of forcing people to prove their citizenship. I think that is the first instance of violence. It is the first instance because one is made to undergo a whole lot of paperwork on their own, and there is no support of any kind until the state came up with a list of guidelines after the final list was published on 31st August last year, saying that they will provide legal aid. But, before that, people were on their own, and of course, there were a lot of illiterate people. This is a rather cumbersome process, and this whole process of documents will certainly require a lot of help from people. Forget about finding the document, just the file, and you know, to come and submit itself is an uphill task. Now, if there is a mistake in the document, you get notified. That correction procedure takes another whole lot of journey. So, in one such instance, when you are being notified by the Foreigner’s Tribunal, there’s a hearing of your case, and people are made to travel almost 400-500 kilometres on a notice period of 24 hours or 48 hours. And, I think, last year there were a couple of road accidents of people travelling to present themselves in these cases. And I think close to 68000 ex-parte judgements being made where these people were declared foreigners when they were not even there to defend themselves. So, I think that kind of impatience on the part of the state signals a lot within the system, but, at the same time, people have been thrown everywhere to just run around for a piece of paper to prove their identity.

The other thing related to that is violence in terms of how people are deeply affected by it psychologically and the number of suicides that have taken place in the past 2-3 years in Assam. People are being made to undergo so much pain that they have decided to kill themselves. These are hard, physical evidence of trauma and anxiety, but I am sure many more are deeply troubled. If you look into the cases of suicides, you know there are different kinds. It’s not only people who are victims of the NRC process, meaning those who are not able to prove their identity and were declared foreigners or were in an uncertain limbo, sort of a phase, and they decided to kill themselves.

I think the third kind of violation is people who are detained and kept in detention centres, as you pointed out. They are being subjected to more than inhuman treatment in these centres, and there is no aid of any kind, and they have been kept away from their families, from their kids. I think there were a couple of cases where both the newborn and the mother had to be in detention, kept away from family. And so far, if I am not mistaken, there have been 25 cases of death in detention…

Q: We have been following that, and I think right now the number of deaths in detention is 31, if I am not mistaken…

A: I See. Okay.

I guess…I mean, these cases have only increased over time, and I think there were families who refused to receive the dead bodies in a couple of cases. In at least three cases they won’t receive their family member because they were declared as a Bangladeshi or a foreigner, and unless and until they declare them as Indian, they won’t accept their bodies. And I think in one case, two ministers from the state ensured that they would do everything to handle the case and see that the person was declared as Indian and only then the family accepted the body.

So, this kind of posthumous citizenship is not something new, and it can go a long way in healing the pain of these victims and their families. Israel, in 1985, gave posthumous citizenship to all 6 million Jews, and there are lots of cases of posthumous citizenship being granted to undocumented soldiers who either suffer death or any kind of serious injuries in war in America. So, we can certainly sort of talk about the possibilities of posthumous citizenship, at least in the context of NRC, where these people are severely undergoing different kinds of trauma.

So, this procedural violence can then be located through these different institutions, which refuse to hear the pain of these people and have remained very problematic. I have come across a case where this person defended his case seven times in the foreigner’s tribunal, and each time, he could prove he was not illegal. So, these cases keep bouncing back, and there is no accountability whatsoever, and people are made to run pillar to post and spend so much money. I think the kind of expenditure made just to become a citizen in Assam is mind-blowing. This image is of a Muslim man trying to dry his papers in a flood relief camp in Bodoland. And that image was very gripping because oftentimes you see people leaving their homes, trying to guard their cattle and their grain and maybe some other valuable things to go and stay in the relief camp till the flood water recedes. But in this case, there is no such thing. This person was grabbing onto the documents and was sort of laying it out in the open to dry. I think this speaks a lot of volumes about how people are reduced to these documents as if there is nothing more to life than proving one’s identity. What can that sort of a mentality suggest, in terms of one’s urge or one’s love to belong to a particular place, than to, you know, to suffer in terms of how these papers have taken over their lives? I think that’s proof of a kind of nationalism. That is the highest proof that one can have regarding a citizen and how they relate to a place.

Q: But it is also a kind of deep fear of annihilation, correct?

A: Yes.

Q: That, it’s very interesting that you brought up this document because 2-3 years ago, when I was in Assam, travelling. This was before the NRC had happened. I was going to a village to interview someone and …The monsoon had just happened, and a very similar image where the family of the woman I was going to interview, you know, had just again taken these things out, and she was just drying everything. She was drying old ID cards because she was very worried that, you know, the thing would happen…what does the NRC exercise, in your opinion and of course the recent Citizenship Amendment Act mean for the ideas of citizenship?

Also, you very eloquently talk about this as the highest form of nationalism. For me, it is also a point where…for many in India now, this is also a point of absolute annihilation—absolutely manufacturing a class of undocumented class of stateless people. So talk to us about this idea of citizenship after NRC, after the Citizenship Amendment Act.

A: Right. I mean, I think it’s kind of an irony. It’s often said that South Asia is the graveyard of social theory, where all kinds of analysis fall apart. But it now appears that Assam is the graveyard of Indian citizenship and democracy. Now, I suppose there are a lot of implications as we can already see that I have tried also to put it out that there is a very organic link between NRC and CAA or CAB earlier because the Citizenship Amendment Bill (CAB) 2016 was primarily introduced to accommodate the Hindu “Bangladeshis” who could have been left out of the NRC process. So, you can see that CAB’s main intention was to accommodate these people who belong to a particular religious group within the so-called illegal citizens, illegal people. Now, if you look at that organic link, you can see how the NRC becomes the main point from which everything gets pulled out.

Now, the Indian state wants to conduct an all-India NRC, but right now, they are calling it NPR. They are trying to push this idea that this is not NRC. But there are a lot of similarities if we go back to the 1951 NRC with the NPR, which is just a documentation of people in various districts in India. So, this will seem as if, it is a census-like document, but then this will become the basis of a full-fledged NRC at some point.

Now, if I may digress a little bit before I come to your question, here I am just speculating why 1951 became the base year for NRC; why not any other year? And I started looking for reasons because you can see a lot of assertions being made by different kinds of actors and institutions even to push the Assam NRC date to 1826 when, you know, the Treaty of Yandabo was signed, and formally British came into the North East. So, why not, say, for instance, 1901 or 1921? I think the rationale for 1951 NRC is not in 1951 NRC, but 1951 becomes a date for a base year rather for NRC, and the rationale is to be found in the Census of India — the way you know, the census changed in India.

So, there is a very interesting study by the scholar in JNU who wrote this dissertation in 1977 – Neelufar Ahmed. Ahmed talks about the problems of the census data. And the study by Ahmed was conducted between 1891-1931. Now, there are a couple of problems. To start with, back then, districts were the smallest unit of measure in the census, and districts were quite huge at that point in time. There were only ten districts in Assam in 1891, which has now grown. The second problem then associated with the bigger districts had to do with how many states were carved out of Assam–Meghalaya and a couple of other states. So, lot of shifting of boundaries and districts – not only district boundaries but also state boundaries took place. The third problem, Ahmed points out, is that only in-migration could be documented. So, the place of birth of a person was never documented in the census earlier on, so out-migration is not possible to be located within this data. The fourth problem associated with the census till 1931 is that…also the motive of the migrant was not listed. Now, these four things combined pose a problem. So, until 1931, these problems remained, and I think this is extremely crucial in understanding why the year cannot be pushed beyond 1951. And now there is an associated problem along with this problem. The other crucial thing to note here is that the nature of the census also underwent a change. For the first time in 1941, we see that the census started sort of also documenting certain changes within these four things I spoke about. So, there was a lot of reorganization within the state, and also, the kind of migration flows were increasing into Assam.

Earlier, you know, a lot of migrants were mostly settling in places like Goalpara 48:08-48:10 unclear district and its adjoining areas but changed later on. It’s very interesting to note that a term like ‘invasion’ was used not to designate migrants coming outside the state but was used rather to designate migration within districts. So, you see how this sort of outlook changes. Or rather, this outlook of…which is usually now attached to so-called illegal migrants, was not really to designate with that intent. It was not used with that intent in the census, but then it became something else. it is not possible to push beyond 1951 precisely because, prior to 1931, you cannot tell who migrated from where. So, that is precisely one of the reasons why 1951 became the base year because in 1941…again, there is a problem because of war. The census remained incomplete in India. So, the data, the kind of data that is required, is not available throughout India, and most likely, it also did affect Assam in many ways.

So, I think, again, I am saying this is mere speculation on my part here to look at why one is unable to push the base year beyond 1951. But then, I think this carries a lot of implications in terms of nationwide NRC. Now, if 1951 is the base for Assam, then what will be the base for India or if at all, there will be a sort of time-frame given for the rest of India like it was in the case of Assam between 51 and 71?

So, what remains crucial is that this becomes like our ex-Chief Justice pointed out that NRC is a future document. So, this becomes a referent in a way for future NRC on an all-India scale. And I think this again for me is very problematic, and like you said, we are sort of underwriting our own annihilation in the process, and whether we participate in this process or not is a different thing. that whole poem that goes around – kaghaz nahi dikhayenge but I think not to be able to show, I mean that itself carries a lot of weight. To not show…

Q: And privilege of caste and class…

A: Yes, exactly. To not show implies that you have the document, whereas there are large sections of people who do not have it and that in no way suggests that they are illegal or it is just that we have migrated so much. Our entire labour class, the social underclass that we find in cities in India, have migrated from different rural areas in India and like Ashish Nandy puts it, in these ambiguous journeys people have made, there was no culture of preserving documents, and we were never told that after 7-8 decades of independence, one will be asked to prove ones belonging which is preposterous. I think this is the pinnacle of humiliation one can undergo –to be told to prove that you don’t or rather told that you don’t belong here after having lived for so many years.

Q: Also, the basis that all those residing within the territorial borders of India are assumed illegal before proof also goes against the fundamentals of a “secular constitution”. Having said that, I very quickly want to go on to this idea again of characterizing the NRC as… a very exceptional or a totalitarian nightmare, but in reality, it is neither exceptional nor totalitarian but something that is procedural violence with a having a long history. Can you speak to us about this nature of unexceptional but ongoing violence that is the NRC and how institutional bodies have inflicted this on the people of Assam and now throughout India?

A: Right. So, let me start with an example from my hometown, Sadiya, in the easternmost part of Assam. During my doctoral fieldwork, I have encountered a couple of families who are currently Muslims. They write usual titles like Ali, Khan, and so on and so forth. And then, I have also met a set of people, a couple of families, who write typical “Assamese” surnames like Dutta, Baruah and others. Now, during the NRC verification process, it has come to light that their ancestors who were living in Sadiya belong to opposite religions. The people who are now Muslims were caste Assamese, and the people who aren’t, who are Assamese right now, were actually Muslim Bengalis. Now, these people, particularly the ones who are Assamese and were Muslims earlier on, have come to face a lot of, if not ostracization, but avoidance from a lot of people knowing that they were Muslims.

Now, you see, I would say NRC has opened up these unnecessary wounds. This very fact of people having to change their cultural identity, even religious identity in Assam, in the face of different kinds of nationalistic oppositions from different actors was highlighted by a lot of commentators and reporters back in the days of the Assam Movement, and one of them is the very brave, Nirupama Borgohain who also suffered a lot at the hands of the nationalists. She pointed out during her report that many Bengali families who converted to Assamese have given up their language and culture to remain safe. Does this sound very familiar to the kind of fascist onslaught we see or hear, say from Gujrat or even UP? This, I think, is an extremely problematic and deeply traumatizing development or rather a history and something very similar if not changing or acquiring different cultural and religious domains.

A lot of research also has shown how there was an increase in ghettoization of people in UP after Ayodhya, which wasn’t so apparent before Ayodhya. So, something very similar is happening here, and of course it’s not replicated in this same manner, but the history of Assamese nationalism shows that this kind of animosity between different groups, religious, cultural and linguistic, has led to very traumatic experiences for the minorities in the state. Oftentimes, if we speak about the Nellie Massacre in Assam where thousands of people, I mean, the official numbers say stands at 2000, but I think the unofficial count goes up to a few more thousands were killed not with guns but with knives and other kinds of spears. And this happened at the peak hour of the Assam Movement, and who is responsible for this? And of course, all the leaders, including Prafulla Kumar Mahanta and the Assam Sahitya Sabha – the cultural, literary body in Assam and all others tried to absolve themselves of this whole heinous act of murder and annihilation of people and these people who were targeted belong to a particular community, and there is no denying that this kind of wounds will certainly be opened up and this whole NRC process has sort of antagonized a lot of people and also woken up and a lot of this kind of ethno-nationalist sentiments and particularly with the…Citizenship Amendment Act protest, we see in Assam, it’s deeply disturbing for many of us and for people here and they often say that the protest in North East or Assam is very different from rest of India. But before we go into that, one can, I mean, one should really look into the nature of protest that is happening in the East, and it fascinates me.

I have been to a couple of them to see public protests and how they are being organized, and what I saw was deeply tumblehome. I mean, it was worrying to see how as if hate has become respectable in our society and hate for the outsider was sold out like commodities by these artists in Assam. And I think with the CAA protest, a whole new generation of students, particularly students and the younger generation in Assam and North East, is being baptized by the same kind of leadership, the same kind of regressive leadership that led the Assam Movement. The new generation is being baptized with the same kind of politics, to hate the outsider, and this is deeply problematic.

And even if you look into the aesthetics of the protests here, it’s so powerful. There are a lot of videos shared where young students from schools and colleges…undergrad colleges, were cutting their own arms, and with the blood, they were writing different anti-CAA posters into papers, into the gamacha – the cloth that you see with red borders and white background. And this invocation of blood and soil is very powerful and problematic at the same time. It remains very problematic in terms of the kind of discourse it appeals to, and that discourse is definitely one of martyrdom, and that martyr discourse then easily slips into the discourse of violence.

Often times you hear that the protest is different from mainland India and how it is organized here. They tend to say that we are very secular here. In a sense, they are saying that we don’t want both Muslims and Hindus, and that’s why we are secular. I think this is the very limited understanding of what is secular and what is communal. I mean, the understanding of secular is not only premised on religious grounds, but such an outlook for me lacks an appreciation of cultural diversity, history and a whole lot of things.

Q: I just want to finish our podcast with one last question. There have been a lot of complaints from Assam, especially from a generation of young scholars and activists saying how mainstream India does not document or report on these protests properly. For example, there has been immense violence on the protesters; there has been an imposition of curfew, you know, five protesters have been shot dead in Assam, there is teargas, there is a lathi charge, and of course, activist Akhil Gogoi has been arrested. It also puts one in this position where one is trying to understand, as you rightly talked about how you can’t have, you can’t say you are secular and say we don’t want either Muslims or Hindus, you know, but I was kind of wondering what your take on this was that do you feel that there is a protest movement that is happening that can actually be one that is not baptized by hate. Does that possibility still exist? What do you think about that, or do you think all of these protests are so now colored by a certain sense of Assamese nationalism?

A: Right. I mean, as far as I have seen, I haven’t seen anything but hate and this kind of coloring that you talk about, it’s far too powerful, and that is the dominant discourse. We are forever trapped in that discourse of the Assam Movement, and a new set of people are now followers of that discourse. And to give you an example, the artist society has come out and is leading the protest in Assam. One of the usual slogans used in protests, if I may roughly translate, it says — ‘O come out! Please, everyone, come out! Let’s chase the Bangladeshi!’ This keeps on reverberating and being used everywhere. These are some of the lyrics of the song, and there is much more problematic stuff in it. So, this kind of discourse is so powerful and sediments the kind of hate for the outsider and, here in this case, the “Bangladeshi”. I don’t see, as of now, any kind of protest outside this discourse, and this is also not to say that there isn’t a possibility outside this discourse. I mean, I do have hope or rather, I do say that there is a possibility beyond this dominant and ethno-nationalist discourse because there we have had a lot of intellectuals in the 40s and 50s who tried to appeal to people and did write different kinds of material, be it songs, be it music, be it plays, and so on and so forth, which spoke of a multilingual, multicultural Assam and in their articulations and here, I am referring to people like Jyoti Prasad Agarwala, Bishnu Rabha who did accommodate everyone to talk about cultural identity, talk about a linguistic identity of people and in their articulations we find, a celebration of the beautiful, celebration of a culture which is invested in beauty. And I think that sort of cultural philosophy one needs to really critically engage with, and I think the possibilities can come from people such as them who are also considered as cultural icons in Assam, but the way they are being used or rather appropriated creates a sensation of ethnonationalism and sanitizes the kind of multicultural accommodative politics they spoke of.

And to your last point about misreporting and underreporting, I think that is true to a large extent, and I would also like to add that underreporting is not just in the case of protests but it is a general sort of practice or experience and this underrepresentation is not just in terms of media but also in terms of intellectual practice that we find, the kinds of history that are written. How the histories of people, culture, society and language of North East never find mention in any curriculum in schools in India and even if they do, it’s perhaps very recent or just in passing.

So, these problems are more structural. They are inherent not just in terms of how the media reports them but also, I think, are present in different ways, which brings about a kind of lacuna and problem in understanding and explaining the whole region of the East.

And lastly, I think what I have sort of tried to highlight in my writings is that, yes, we do need to be critical about how we are being looked at or understood, written about by people from outside, but at the same time, it’s also very cynical and childish even to assume that someone who does not belong to North East cannot understand the concerns and commitments of people here. And at the same time, we need to be critical about our culture and society and how we look at the minorities in Assam or in North East, and I am not talking about minorities in terms of who is seen as a “foreigner”, but I am also talking about minorities in terms of different tribal groups, different indigenous groups who are not in that power structure, who do not command that kind of power in different states in North East. I think the focus is very, very necessary and not just a complaint on the part of how we are being thought of, imagined and are written from the outside but that internal differences and distinctions are also very necessary to be highlighted if we do think of critical scholarship in the future.

SUPPORT US

We like bringing the stories that don’t get told to you. For that, we need your support. However small, we would appreciate it.