Resistance and pain beyond words — Challenging the narrative warfare in Kashmir

Starting from The Last Call: Audio Postcards from Kashmir, Suchitra Vijayan and Uzma Falak discuss the “impossibility” of speaking about violence in the context of the occupation in Kashmir, the role of poetry and visualization, and the space of singularity as a site of cultural and political resistance. Uzma Falak is a DAAD Doctoral Fellow at the University of Heidelberg where she is pursuing her PhD in Anthropology. She tweets @Uzma_Falak

“These narratives of death and departure

are in fact narratives of life and arrival”

Suchitra Vijayan: Writers like Sebald have used ‘found images’ as a way of bridging the gap between the reality of the terror they witnessed (in case of Sebald, the Holocaust and post-war Germany loom large in his work) and the inadequacy of language. Similarly, Orson Welles used found footage of Elmyr de Hory from a BBC documentary for his F for Fake.

Can you tell us what made you use these visceral audio goodbyes to write about the nature of violence and resistance in Kashmir?

Uzma Falak: I am incapable of telling a story. I experience and witness the world in fragments. Through my work I attempt to record this fragmentariness. The Last Call: Audio Postcards from Kashmir is also a fragmentary chronicle — several disjointed pieces on the verge of a story. It is a chronicle of an ongoing war that is constantly inscribing itself onto us and turning both remembering and forgetting into a complex entangle.

This work was born out of an almost mournful disquiet surrounding the notion of time. A crisis of time. This is in turn linked to the questions of language and witnessing.

Let me unpack this a bit: I feel loss slows down time. But our world is characterised by an accelerated time — an official statist time driven by the rationale of the market; a militaristic, occupational, neoliberal time marked by linearity. This temporality permanently tends towards ‘moving-forward’. There is a discordance between the temporality of loss and the official temporality. It is this crisis I grapple with. These found audio-recordings also foreground this discordance.

In 2012, members of ‘India Inc.’ visited Kashmir and one of its executives told the people: “Forget the past and try and make up for the lost time”.

In March 2018, entrepreneur-guru and Art of Living founder Ravi Shankar (self-anointed Sri Sri), acting as the Indian State’s go-between addressed a gathering in Kashmir and pontificated: “Forget the past and move forward.”

This systematic and ideological prescription to move forward is indicative of the State’s desire to continue its military occupation in Kashmir while making it a marketable commodity. But what does it mean to move forward in a militarily occupied region where, for instance, people’s mobility even in its literal sense is impeded and feared? Where people embody a temporality of loss? It is the refusal to comply with the statist vision of moving forward, the refusal to embody a statist temporality, which is at the heart of people’s resistance in Kashmir.

There is also a chasm between experiencing a loss, witnessing it, transcribing and translating it through language. We find ourselves repeatedly caught between a feelinglessness imposed by the moving forward regime and an obligation, an urge to feel; between exhaustion and urgency.

These farewell phone calls engender a haunting affectivity that constitutes alternative ways of knowing by challenging established temporalities, spatialities and modes of being characterised by linearity, homogeneity and presence. These calls enable us to traverse other temporalities and modalities of being marked by complex relations to past, present and future, presence and absence. Resistance is this in this chasm, in this in-betweeness shaped by the struggle of and with time, loss and language, incompleteness and inadequacy and it abounds with radical possibilities. It is here, for instance, that the poetic dwells. By poetic, I don’t necessarily mean poetry bound in a written word. I mean an encounter with the poetic in an everyday, embodied sense. A body in pain, I write elsewhere, is both a site of destruction and an invention of language. For example, screams, shrieks, grunts, cries are all utterances of pain as well as a resistance to language caged in grammar. In its articulation of pain through language, a body in pain, evokes metaphors and experiments with forms, experiences, senses. In Kashmir we have exhausted all metaphors of pain. Kashmir itself has become a metaphor of pain.

The Last Call: Audio Postcards from Kashmir is an extra-linguistic cry, an utterance formed by the radical potentialities of the chasm I attempted to sketch above:

Last words that beckon all words to assemble in grief

ripping their apparels of meaning apart

donning instead shrouds of incomprehensibility

setting language free — Wai

It is a plea for the time to stop:

If time had feet they would forget how to march ahead

callously across the delusional seasons

They would instead keep walking backwards

back

back

reversing its own forgetful stampede.

If time had a heart of the occupied

it would forget to tick away

just like that

These farewell phone calls are impossible conversations, marked by unfathomable ease, patience, silence, love and ordinariness. And in a way, the piece addresses its own impossibility: this is not a poem or last words that make a poem difficult.

Found material has a long history across disciplines and has been used in several contexts including poetry, towards various possibilities of criticality and subversion. Sebald used found photographs for their mnemonic capacities. Even though his work problematises the questions of authenticity, for him the indexicality and referentiality of the photographs were still of primary importance.

The found audios I worked with question the very authenticity of history and history writing; they also problematise the notions of archive and memory. These found audios challenge the grand narratives which look at Kashmir as a territorial dispute or a security issue, where the people of Kashmir are absent thus masking their histories. They undo the statist project of dehumanisation, victimisation and pathologisation of the resistors, who are reduced to numbers by the State. These recording set forth a process of restoration and rebuilding. In my exploration of writing as site of loss, struggle and survival, I attempted to work through an intertexuality between these conversations, my own complex encounter with them, the State’s security and military jargon and perception management by the media strategies. I attempt to create several layers of meaning, to enable a poetry of witness, poetry as witness and to foreground the testimonial force of these phone calls and their transcripts.

Through this work, I initiate and join a human chain of witnesses within (and beyond) the space of writing itself and I allow it to extend its hands to other witnesses.

SV: How did the material come together?

UF: It’s been a few years since I have been listening to and collecting the recordings of these last phone calls. In April, when I had woken up to the sound of spring rain inscribing itself on the remnants of German winters, 17 people had been buried in Kashmir. Rain has an uncanny relation to death and funerals in Kashmir; ro raha hai aasmaan (the skies are weeping) is a resonating cry at the funerals of martyrs. As it rained in Heidelberg, and the audio-recording of Aitmaad’s last call reached me at my breakfast table, I felt an intense haunting and was unable to carry on after what I had heard: a boy with a bullet in his head speaking over the phone: “Excuse me I am stammering, I have a bullet in my head. Do you have my father’s number?” The manner in which these recordings punctuated the ordinary moment of an ordinary morning rupturing a superficial continuity by resurfacing loss as well as the record of the ordinariness in the calls itself left me unsettled.

I began writing out of a desperate and compulsive personal sense of urgency. The work came to life in fragments and is divided into eight sections. I first wrote fragments Three and Four in my attempt to come terms (or not) with the impossibility of these conversations. I soon found myself entering a strange territory. I heard Aitmaad’s call several times. This was followed by listening to the ones I had already collected. This continued for several days. Each day I would carefully listen to the calls, one after the other, transcribe them followed by translations, which I wrote and rewrote several times. The loss and resistance in the everyday expressions in Koshur, Kashmir’s native language, struggled to find a home in English. I wanted to foreground this violence and I retained some expressions in Koshur. There was much that couldn’t be transcribed like the silences, or some utterances which defy expression, or the grain, rhythm and tonality of voices, the texture of the recordings which contributes to the visceral affectivity of these calls. The feeling of incompleteness was intense and, in the end, I gave up as I understood the poignancy in incompleteness. This incompleteness is an important marker of these phone calls. There is no closure even when the call ends. When one tries to scavenge presence (of something lost) from the bottomless pit of absence, one actually becomes a scavenger of absence and there is no end to fathoming the absent. It is an enormity that manifests itself into the infinitesimally minuscule and always elusive, but at the same time it resists exhaustion. In this sense, coming to terms with incompleteness and employing it as a formal choice and method hopes to do justice to such elusiveness.

The transcriptions and translations are not unmediated and I attempted to foreground my own encounter with these recordings, exploring my own vulnerability as a vehement, critical force. I was working with multiple voices and silences including my own; with multiple languages, texts and contexts. Not only did I feel uneasy about the translations, but also about the image of the text. No appearance seemed adequate enough to inhabit the nature of these calls. I dismembered and rearranged the text each time I revisited it. This struggle is not unrelated to the ‘unspeakability’ and inadequacy of language and form. I wanted to visualise this tension by rendering the form itself, in a way, hysteric, without losing sight of the criticality and the ethical-political engagement. In the end, I settled with dividing each phone call into the voice of the Witness, the insurgents, and the voices of the Witness to the Witness, friends and family who received these phone calls. I deployed a theatrical idiom to foreground my encounter with these phone calls as impossible. Words like Enter and Exit, for instance, enabled the text to dangle between the possible and impossible. Call Ends became a way of bridging the phone calls while capturing a difficult rupture in these intimate conversations in a matter of fact way. This ordinariness brought to fore the intensity of loss in the precise moment when the phone gets or is disconnected. Similarly, the indication of Call waiting tone or the interjections within parenthesis act as both interruptions and ways of limning the textures of loss and survival.

In Fragment Five I list the names of the military operations in Kashmir. In Fragment Six I subvert the statist jargon, interrogate it, and re-deploy it in the context of my piece to create a contrapuntal narrative and explore possibilities of subversion and resistance within language, challenging binaries associated with both resistance and ‘art’, and attempting to re-imagine the terrain of the poem itself.

The bench for the wayfarers, lovers and homeless, in the last fragment Marginalia, became a way to register my own voice, recording my quotidian encounter with the bench— a place away from home, where, both physically and symbolically, these dispatches from home could be received. The final portion in Marginalia was added much later, in fact, after I submitted my initial draft to Warscapes magazine as a voice of absence, a plea and a prayer, where I had to accept myself as one of the Witness to the Witness.

SV: Audio Postcards – the phrase is evocative and conjures many metaphors. What made you use this title for this work?

UF: Kashmir has been constructed as a postcard-perfect Paradise on Earth; a romantic, syncretic antiquity frozen in time. This colonial project of exoticization, commodification and fetishization has been systematically executed to normalize the military occupation in Kashmir and has led to an erasure of people’s histories. Tourism and statist cultural production have been instrumental in strengthening the facade of ‘normalcy’ and ‘peace’.

As I write elsewhere: “Our lives have two versions. We live in two contested worlds – the one we breathe, see, taste, feel, hear, smell and the one which settles on our skin like a fragile layer of dust. A world born out of the Indian state’s violent cartographic act through which it claims Kashmir to be its atoot aangh, integral part; a world characterized by the absence of our histories and stories”. The portrayal of Kashmir as happy and normal and its construction as a paradisiac landscape is linked to the Indian State’s claim of Kashmir being its integral part.

Such a project is also systematically used to evoke a desire for Kashmir. This desire is channelled to produce anxiety for the idyllic Valley, which is further employed to engineer consent and justify the occupation and the statist violence in Kashmir, a place which haunts India’s sovereignty and post-coloniality.

Visuality has been an important tool in this machinery for the production of desire, anxiety and consent by the colonial-state-security-military-industrial-media complex in Kashmir. An oppressive, militarist, colonial regime or a right-wing populist regime, is essentially a visual regime sustained by image-building, advertising and public relations. Think for instance about Vibrant Gujarat and Narendra Modi’s image improvement by APCO Wordlwide or to the attention to details in his election campaigns: dress-code, body language, gestures, gaze, are all quintessential to the advertising and publicity toolkit.

In addition to imperious visuality, State’s efforts have been directed towards rendering Kashmir soundless and turning it into a sound-proof zone. However, the people of Kashmir have worked to create an alternative visuality and aurality undoing these processes of erasure. The phrase ‘audio postcards’ for these dispatches from Kashmir addresses these complexities and offers a counter-narrative to the State’s hegemonic cultural production, memory and archival practices.

SV: You have used the recording of Dar and Lone in your visualization, can you tell us little about these two men and about events leading up to the last recordings.

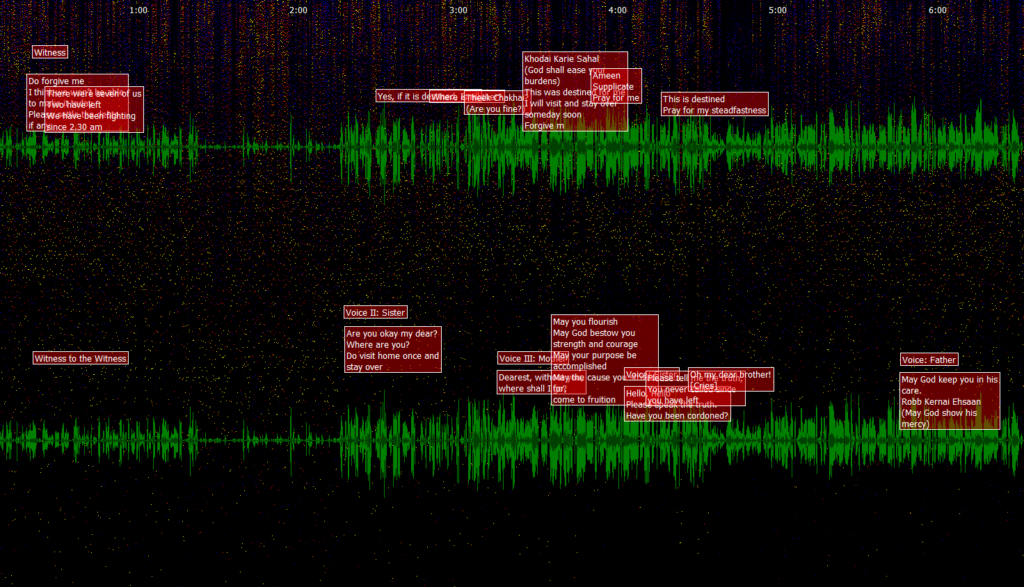

UF: Through the visualizations of the recordings, I worked towards an alternative visuality. For instance, the undulations of the sound waves and the shape of the waveforms symbolically evoke the mountains and rivers of greetings and supplications, gorges and crevices of farewells and promises, and pastures of silence— wai, lagya vanidth, varie, salaam, the crests and troughs of resistance.

On April 1, 2018, thirteen insurgents and four civilians were killed in three separate encounters — two in Shopian and one in Islamabad — in Kashmir.

The visualizations are about the audio-recordings of the last phone calls that Aitmaad Hussain Dar and Sameer Lone made to their families from the encounter sites few hours before their death. Aitimaad and Sameer were part of a group of seven militants, who sought refuge in the home of Mohammad Maqbool Lone, a farmer, on March 31; they both were killed in an encounter in Kachdoor village of Shopian.

The armed forces had launched a series of search and cordon operations and had laid siege around a cluster of houses. Two of the seven insurgents managed to break the cordon while the other five, including Aitimaad and Sameer, were restricted inside and had taken positions in the second floor of the house. Maqbool, with the other fourteen members of the family, including an elderly couple and children, were trapped inside the house, surrounded by the heavy presence of armed troopers for about 10 hours and were only able to leave in the morning.

Aitmaad and Sameer had borrowed Maqbool’s phone to call their families for their departing conversations.

A resident of Amishpore in Shopian, Aitmaad, in his late twenties, had joined the insurgents on Nov 5, 2017. His father, an apple farmer, says he had “lost a debate” about life and death with his son and couldn’t stop him from picking up arms. “I asked him to rethink about the path he chose. However, my son said he would return if I promised him he would never face the reality of death. I could not convince him,” his father was quoted in a news report. Aitmaad had returned to Kashmir after completing his MPhil in Urdu from Hyderabad University and wanted to pursue a PhD before he joined the militants. An undergraduate student, Sameer who is heard speaking to his parents and siblings in the recording, was a resident of Hillow village in Shopian and had joined the militants only a month before the encounter.

Over 200 people were injured in the protests and funeral processions that followed and several people were hit by pellets in their eyes. Maqbool’s house was completely destroyed. The morning saw remnants of a charred home and the dead.

SV: The nature of artefacts, archive, and memorialization are rapidly transforming in the age of WhatsApp. These dispatches from the encounter sites, as you argue, are widely downloaded and shared despite internet and digital crackdown. Can you tell us a little more about how these recordings have become a part of the Kashmiri collective consciousness and resistance?

UF: These recordings capture ordinary details of departing lives. These affective practices of speaking and listening, these intimate, mournful and poignant conversations are people’s archives and memorials constituting a counter-public. As opposed to the State’s fossilized, static and closed archives marked by colonial obsession, chronology, continuity and repressive erasure, these people’s archives rupture the statist continuity and challenge historiography. The strength of these people’s archives lies in their ephemerality and openness that offer critical possibilities. These recordings lie at the intersection of history and memory, they imbue both with new meanings and offer alternative imaginations of past, present and future.

In Kashmir, the State has exercised a monopoly over which lives are deemed grievable. It has thwarted funeral processions and funeral prayers, opened fire on mourners, delayed handing over of the dead to their families and sometimes denied it altogether (an open grave in Kashmir still awaits the mortal remains of both Mohammad Afzal Guru and Mohammad Maqbool Bhat who were sent to gallows in New Delhi’s fortified Tihar prison). Amid such clampdown, these recordings of the last phone calls are important conversations that allow people to mourn and enable the transformative possibilities of mourning. These recordings challenge the State’s efforts to deny people the parting words and accounts of their loved ones and the witnesses – Afzal Guru’s wife and son weren’t informed of his execution and were denied a last meeting. The callers – the insurgents – through these conversations claim the familial bond and trust which the State attempts to rupture. These conversations reinforce the trellis of support and care that nurtures the resistance in Kashmir, they transform the familial relations and imbue them with new meanings, creating a greater family, beyond blood ties: a network of solidarity, a human chain of witnesses and resistors.

While the State fosters mistrust and barbarity, these recordings and their dissemination reverses this process and forges compassion. It is this poignant force of compassion and resistance, compassion of resistance and compassion as resistance that the State is anxious about. A police officer, referring to these phone calls and their wide circulation, told the press: “It is a dangerous pointer. It shows how dying is being glorified by the parents themselves and the family support lent to trapped militants.”

While in many societies and cultures death and the dead remain a taboo, in Kashmir death, the dead and narratives of death are part of the everyday. In this sense, these audio recordings of the last phone calls invoke and cite a transformative eschatology allowing the family and friends and the larger circle of supporters to come to terms with their separation thus allowing a sense of continuity. These conversations cite death as a continuation or a transition. The transiency of life and the certainty of death are evoked, to define an ethicality of living. The callers bind their family and the listeners into an ethical-political engagement that constitutes them as ethically responsible beings. Families are reminded to settle their debts, forgiveness is sought for broken promises, while new promises are given and taken, reassurances of meeting again are pronounced, and the value of a life fighting oppression and falsehood is emphasized. These phone calls imbue a new meaning to closure. In these last moments of death, life is lived converging the power and promises of past, present and future. These fearless conversations reaffirm the certainty of death, but also reaffirm life. These narratives of death and departure are in fact narratives of life and arrival.

SV: The nature of unmitigated violence in Kashmir sometimes makes narrating this violence and its repetition difficult. Do you see new narrative forms of expression emerging?

UF: There are several layers to this question. In your first question you talk about the inadequacy of language in relation to the Holocaust. I think this is also relevant here.

Jean-Francois Lyotard compares Auschwitz to an “earthquake that destroys not only lives, buildings and objects but also the instruments used to measure earthquakes directly or indirectly.” He further notes: “The impossibility of quantitatively measuring it does not prohibit, but rather inspires in the minds of the survivors the idea of a very great seismic force”. Prompting considerable debate, Theodor Adorno wrote: “To write poetry after Auschwitz is barbaric,” which he later retracted by saying: “Perennial suffering has as much right to expression as a tortured man has to scream; hence it may have been wrong to say that after Auschwitz you could no longer write poems.” Though one must be critical of dividing the history into before and after Holocaust and challenge its centrality to history writing without diminishing the horror of violence and persecution (of not only Jews but other minorities as well, like the Sinti and Roma), I think Adorno’s statement and his later retraction and Lyotard’s reflection point out to the inadequacy and limits of language, the unspeakability, the impossibility of narration in such circumstances. However, in some sense, it is the “great seismic force” of unquantifiable and unfathomable unspeakability that eventually displaces the ground of impossibility, consuming it in its own force – making the ‘scream’ possible.

Even though poetry was written during and after the Holocaust and continues to be written amid utmost barbarity— in the cells of Guantanamo, amid airstrikes in Syria, under siege in Palestine, massacres in Kashmir, lynching in India, and several other ‘nameless’ places which haunt the dominant history and history writing practices – impossibility as a motif is a profound marker of such narrations. Such work employs self-referentiality and points to its own impossibility.

For example, in Poems from Guantanamo, Sami Al Haj, a Sudanese journalist who was covering the war in Afghanistan in 2001 and was tortured at Bagram air base and Kandahar before he was shifted to Gauntanamo, writes in one of his poems:

I was humiliated in the shackles

How can I now compose verses?

How can I now write? After the shackles and the nights and the suffering and the tears,

How can I write poetry?

Similarly, Abdulla Majid Al Noaimi — a citizen of Bahrain who after an unsuccessful search for a missing family member in Afghanistan made his way to the Pakistani border where he asked the authorities that he be taken to the Bahrain embassy but instead the Pakistani authorities turned him over to the U.S military— writes in one of his poems collected in Poems from Guantanamo:

So I set out to write but I could not concentrate on the poem. I put poetry writing aside and turned to memorising the Quran. But then I could not concentrate on the Quran, because my mind was occupied with the poem. With my mind divided, time began to pass. And then I was inspired: My heart was wounded by the strangeness

Now poetry has rolled up his sleeves, showing a long arm

These haunting poems from Guantanamo emerge from, as Ariel Dorfman writes in the epilogue to the book, “the simple, almost primeval, arithmetic of breathing in and breathing out”. In Kashmir too, the source of these narratives is a fierce sense of hope and survival, and these are chronicles of the impossible “arithmetic of breathing in and breathing out”, even though the conditions for breathing (both literally and figuratively) are made impossible, unthinkable.

In Kashmir the State’s war on people manifests itself not only as a direct military control but as a systematic, ideological war; a cultural war, a war of narratives and words, a war waged to control desires, choices and wills, bodies, resources and land. Understanding violence, unpacking its knowability and unknowability is an uphill struggle. More so when the nature of such violence, as you point out, is repetitive and unmitigated, marked by a constant and repeated inscribing and re-inscribing. Incomprehensibility and unspeakability in relation to loss are intense experiences, sometimes exceeding or amplifying the intensity of loss itself. In addition to these quandaries and the enormity of violence, the state’s efforts in Kashmir are also aimed at systematically destroying the instruments to measure violence, co-opt the mechanisms of resistance, seize and destroy language, impose a narrative control, gag and exhaust the witness. It is a State that kills, blinds and maims, that uses torture and rape as weapons of war and organizes art camps “nurturing cultural heritage and identifying young talent, exposing youth to modern and contemporary art.” It is a State that portrays itself as a champion of women empowerment and organizes motivational talks and psychological and counselling programs. This militaristic humanism has been vital to its war on people.

The State’s stringent narrative warfare that aimed at perception management and public relations is a whitewashing tactic. In this enterprise of narrative warfare, repetition has been a systemic strategy of the occupying regime’s war on people. In the manual of oppression and the templates of violence, repetition is a structural force. Life and death have been subjected to brutal repetition in Kashmir. India’s oft-repeated question What do Kashmiris want? is not merely a buying-time tactic or an entrapment, but it is indicative of how the occupying State exercises repetition as a tool of its sustenance.

The efforts of people’s resistance in Kashmir, on the other hand, have been directed towards retrieving the singularity of every such act of violence. The resistance and its narratives in Kashmir have limned and pointed to a distinct home, a distinct room, a wall, a street, a window, a bullet, a grave, a tree, a body, an eye, a limb, a bone, a life. And at the same time these singular narratives have been strung together into a resonance. In the wake of the State’s homogenizing brutality, its repeated violence and the exhaustion it imposes, the challenge has been to not lose the criticality of this singularity. People’s resistance in Kashmir has reclaimed repetition and used it as a liberatory practice to foster a multiplicity of voices and resonance.

The emerging narrative forms are in a continuum with the rich repertoires of resistance that have existed in Kashmir. These grassroots narratives have employed visuality, aurality and orality encoding resistance into cultural memory. Everyday practices and projects of memory and memorialization are integral to these repertories. The strength of these narratives also lies in their radical lack of closure amid a perpetual war.

In Kashmir, as violence is constantly inscribed on bodies, landscapes, homes and streets, skies and earth, resistance too writes itself over these same sites turning them into critical notions of justice and liberation, into sites of and for narratives rooted in people’s memory. Every home is a memorial, an address of loss, a story of survival. These transformative and restorative narrative practices challenge the State’s narrative warfare.

Language too is one such sites, which shapes and is shaped by people’s experiences and memories of oppression and resistance. In this sense, language not only is a carrier of narratives, but it is a narrative in itself. Silence – as a formal interlude and as a technique in people’s narratives and as an everyday articulation – is one of repertoires of resistance in Kashmir. This silence, redefined beyond the contours of absence and passivity and capturing both the limits of language and the intense force of unspeakability, is agential in its myriad meanings.

Even though narrative forms emerging from Kashmir could be read and discussed within the framework of aesthetics, their strength lies in telling truth to power amid widespread persecution and systemic violence. They inform and are informed by a powerful aesthetics of loss, survival, hope, subversion and resistance.

Related Posts

Resistance and pain beyond words — Challenging the narrative warfare in Kashmir

“These narratives of death and departure

are in fact narratives of life and arrival”

Suchitra Vijayan: Writers like Sebald have used ‘found images’ as a way of bridging the gap between the reality of the terror they witnessed (in case of Sebald, the Holocaust and post-war Germany loom large in his work) and the inadequacy of language. Similarly, Orson Welles used found footage of Elmyr de Hory from a BBC documentary for his F for Fake.

Can you tell us what made you use these visceral audio goodbyes to write about the nature of violence and resistance in Kashmir?

Uzma Falak: I am incapable of telling a story. I experience and witness the world in fragments. Through my work I attempt to record this fragmentariness. The Last Call: Audio Postcards from Kashmir is also a fragmentary chronicle — several disjointed pieces on the verge of a story. It is a chronicle of an ongoing war that is constantly inscribing itself onto us and turning both remembering and forgetting into a complex entangle.

This work was born out of an almost mournful disquiet surrounding the notion of time. A crisis of time. This is in turn linked to the questions of language and witnessing.

Let me unpack this a bit: I feel loss slows down time. But our world is characterised by an accelerated time — an official statist time driven by the rationale of the market; a militaristic, occupational, neoliberal time marked by linearity. This temporality permanently tends towards ‘moving-forward’. There is a discordance between the temporality of loss and the official temporality. It is this crisis I grapple with. These found audio-recordings also foreground this discordance.

In 2012, members of ‘India Inc.’ visited Kashmir and one of its executives told the people: “Forget the past and try and make up for the lost time”.

In March 2018, entrepreneur-guru and Art of Living founder Ravi Shankar (self-anointed Sri Sri), acting as the Indian State’s go-between addressed a gathering in Kashmir and pontificated: “Forget the past and move forward.”

This systematic and ideological prescription to move forward is indicative of the State’s desire to continue its military occupation in Kashmir while making it a marketable commodity. But what does it mean to move forward in a militarily occupied region where, for instance, people’s mobility even in its literal sense is impeded and feared? Where people embody a temporality of loss? It is the refusal to comply with the statist vision of moving forward, the refusal to embody a statist temporality, which is at the heart of people’s resistance in Kashmir.

There is also a chasm between experiencing a loss, witnessing it, transcribing and translating it through language. We find ourselves repeatedly caught between a feelinglessness imposed by the moving forward regime and an obligation, an urge to feel; between exhaustion and urgency.

These farewell phone calls engender a haunting affectivity that constitutes alternative ways of knowing by challenging established temporalities, spatialities and modes of being characterised by linearity, homogeneity and presence. These calls enable us to traverse other temporalities and modalities of being marked by complex relations to past, present and future, presence and absence. Resistance is this in this chasm, in this in-betweeness shaped by the struggle of and with time, loss and language, incompleteness and inadequacy and it abounds with radical possibilities. It is here, for instance, that the poetic dwells. By poetic, I don’t necessarily mean poetry bound in a written word. I mean an encounter with the poetic in an everyday, embodied sense. A body in pain, I write elsewhere, is both a site of destruction and an invention of language. For example, screams, shrieks, grunts, cries are all utterances of pain as well as a resistance to language caged in grammar. In its articulation of pain through language, a body in pain, evokes metaphors and experiments with forms, experiences, senses. In Kashmir we have exhausted all metaphors of pain. Kashmir itself has become a metaphor of pain.

The Last Call: Audio Postcards from Kashmir is an extra-linguistic cry, an utterance formed by the radical potentialities of the chasm I attempted to sketch above:

Last words that beckon all words to assemble in grief

ripping their apparels of meaning apart

donning instead shrouds of incomprehensibility

setting language free — Wai

It is a plea for the time to stop:

If time had feet they would forget how to march ahead

callously across the delusional seasons

They would instead keep walking backwards

back

back

reversing its own forgetful stampede.

If time had a heart of the occupied

it would forget to tick away

just like that

These farewell phone calls are impossible conversations, marked by unfathomable ease, patience, silence, love and ordinariness. And in a way, the piece addresses its own impossibility: this is not a poem or last words that make a poem difficult.

Found material has a long history across disciplines and has been used in several contexts including poetry, towards various possibilities of criticality and subversion. Sebald used found photographs for their mnemonic capacities. Even though his work problematises the questions of authenticity, for him the indexicality and referentiality of the photographs were still of primary importance.

The found audios I worked with question the very authenticity of history and history writing; they also problematise the notions of archive and memory. These found audios challenge the grand narratives which look at Kashmir as a territorial dispute or a security issue, where the people of Kashmir are absent thus masking their histories. They undo the statist project of dehumanisation, victimisation and pathologisation of the resistors, who are reduced to numbers by the State. These recording set forth a process of restoration and rebuilding. In my exploration of writing as site of loss, struggle and survival, I attempted to work through an intertexuality between these conversations, my own complex encounter with them, the State’s security and military jargon and perception management by the media strategies. I attempt to create several layers of meaning, to enable a poetry of witness, poetry as witness and to foreground the testimonial force of these phone calls and their transcripts.

Through this work, I initiate and join a human chain of witnesses within (and beyond) the space of writing itself and I allow it to extend its hands to other witnesses.

SV: How did the material come together?

UF: It’s been a few years since I have been listening to and collecting the recordings of these last phone calls. In April, when I had woken up to the sound of spring rain inscribing itself on the remnants of German winters, 17 people had been buried in Kashmir. Rain has an uncanny relation to death and funerals in Kashmir; ro raha hai aasmaan (the skies are weeping) is a resonating cry at the funerals of martyrs. As it rained in Heidelberg, and the audio-recording of Aitmaad’s last call reached me at my breakfast table, I felt an intense haunting and was unable to carry on after what I had heard: a boy with a bullet in his head speaking over the phone: “Excuse me I am stammering, I have a bullet in my head. Do you have my father’s number?” The manner in which these recordings punctuated the ordinary moment of an ordinary morning rupturing a superficial continuity by resurfacing loss as well as the record of the ordinariness in the calls itself left me unsettled.

I began writing out of a desperate and compulsive personal sense of urgency. The work came to life in fragments and is divided into eight sections. I first wrote fragments Three and Four in my attempt to come terms (or not) with the impossibility of these conversations. I soon found myself entering a strange territory. I heard Aitmaad’s call several times. This was followed by listening to the ones I had already collected. This continued for several days. Each day I would carefully listen to the calls, one after the other, transcribe them followed by translations, which I wrote and rewrote several times. The loss and resistance in the everyday expressions in Koshur, Kashmir’s native language, struggled to find a home in English. I wanted to foreground this violence and I retained some expressions in Koshur. There was much that couldn’t be transcribed like the silences, or some utterances which defy expression, or the grain, rhythm and tonality of voices, the texture of the recordings which contributes to the visceral affectivity of these calls. The feeling of incompleteness was intense and, in the end, I gave up as I understood the poignancy in incompleteness. This incompleteness is an important marker of these phone calls. There is no closure even when the call ends. When one tries to scavenge presence (of something lost) from the bottomless pit of absence, one actually becomes a scavenger of absence and there is no end to fathoming the absent. It is an enormity that manifests itself into the infinitesimally minuscule and always elusive, but at the same time it resists exhaustion. In this sense, coming to terms with incompleteness and employing it as a formal choice and method hopes to do justice to such elusiveness.

The transcriptions and translations are not unmediated and I attempted to foreground my own encounter with these recordings, exploring my own vulnerability as a vehement, critical force. I was working with multiple voices and silences including my own; with multiple languages, texts and contexts. Not only did I feel uneasy about the translations, but also about the image of the text. No appearance seemed adequate enough to inhabit the nature of these calls. I dismembered and rearranged the text each time I revisited it. This struggle is not unrelated to the ‘unspeakability’ and inadequacy of language and form. I wanted to visualise this tension by rendering the form itself, in a way, hysteric, without losing sight of the criticality and the ethical-political engagement. In the end, I settled with dividing each phone call into the voice of the Witness, the insurgents, and the voices of the Witness to the Witness, friends and family who received these phone calls. I deployed a theatrical idiom to foreground my encounter with these phone calls as impossible. Words like Enter and Exit, for instance, enabled the text to dangle between the possible and impossible. Call Ends became a way of bridging the phone calls while capturing a difficult rupture in these intimate conversations in a matter of fact way. This ordinariness brought to fore the intensity of loss in the precise moment when the phone gets or is disconnected. Similarly, the indication of Call waiting tone or the interjections within parenthesis act as both interruptions and ways of limning the textures of loss and survival.

In Fragment Five I list the names of the military operations in Kashmir. In Fragment Six I subvert the statist jargon, interrogate it, and re-deploy it in the context of my piece to create a contrapuntal narrative and explore possibilities of subversion and resistance within language, challenging binaries associated with both resistance and ‘art’, and attempting to re-imagine the terrain of the poem itself.

The bench for the wayfarers, lovers and homeless, in the last fragment Marginalia, became a way to register my own voice, recording my quotidian encounter with the bench— a place away from home, where, both physically and symbolically, these dispatches from home could be received. The final portion in Marginalia was added much later, in fact, after I submitted my initial draft to Warscapes magazine as a voice of absence, a plea and a prayer, where I had to accept myself as one of the Witness to the Witness.

SV: Audio Postcards – the phrase is evocative and conjures many metaphors. What made you use this title for this work?

UF: Kashmir has been constructed as a postcard-perfect Paradise on Earth; a romantic, syncretic antiquity frozen in time. This colonial project of exoticization, commodification and fetishization has been systematically executed to normalize the military occupation in Kashmir and has led to an erasure of people’s histories. Tourism and statist cultural production have been instrumental in strengthening the facade of ‘normalcy’ and ‘peace’.

As I write elsewhere: “Our lives have two versions. We live in two contested worlds – the one we breathe, see, taste, feel, hear, smell and the one which settles on our skin like a fragile layer of dust. A world born out of the Indian state’s violent cartographic act through which it claims Kashmir to be its atoot aangh, integral part; a world characterized by the absence of our histories and stories”. The portrayal of Kashmir as happy and normal and its construction as a paradisiac landscape is linked to the Indian State’s claim of Kashmir being its integral part.

Such a project is also systematically used to evoke a desire for Kashmir. This desire is channelled to produce anxiety for the idyllic Valley, which is further employed to engineer consent and justify the occupation and the statist violence in Kashmir, a place which haunts India’s sovereignty and post-coloniality.

Visuality has been an important tool in this machinery for the production of desire, anxiety and consent by the colonial-state-security-military-industrial-media complex in Kashmir. An oppressive, militarist, colonial regime or a right-wing populist regime, is essentially a visual regime sustained by image-building, advertising and public relations. Think for instance about Vibrant Gujarat and Narendra Modi’s image improvement by APCO Wordlwide or to the attention to details in his election campaigns: dress-code, body language, gestures, gaze, are all quintessential to the advertising and publicity toolkit.

In addition to imperious visuality, State’s efforts have been directed towards rendering Kashmir soundless and turning it into a sound-proof zone. However, the people of Kashmir have worked to create an alternative visuality and aurality undoing these processes of erasure. The phrase ‘audio postcards’ for these dispatches from Kashmir addresses these complexities and offers a counter-narrative to the State’s hegemonic cultural production, memory and archival practices.

SV: You have used the recording of Dar and Lone in your visualization, can you tell us little about these two men and about events leading up to the last recordings.

UF: Through the visualizations of the recordings, I worked towards an alternative visuality. For instance, the undulations of the sound waves and the shape of the waveforms symbolically evoke the mountains and rivers of greetings and supplications, gorges and crevices of farewells and promises, and pastures of silence— wai, lagya vanidth, varie, salaam, the crests and troughs of resistance.

On April 1, 2018, thirteen insurgents and four civilians were killed in three separate encounters — two in Shopian and one in Islamabad — in Kashmir.

The visualizations are about the audio-recordings of the last phone calls that Aitmaad Hussain Dar and Sameer Lone made to their families from the encounter sites few hours before their death. Aitimaad and Sameer were part of a group of seven militants, who sought refuge in the home of Mohammad Maqbool Lone, a farmer, on March 31; they both were killed in an encounter in Kachdoor village of Shopian.

The armed forces had launched a series of search and cordon operations and had laid siege around a cluster of houses. Two of the seven insurgents managed to break the cordon while the other five, including Aitimaad and Sameer, were restricted inside and had taken positions in the second floor of the house. Maqbool, with the other fourteen members of the family, including an elderly couple and children, were trapped inside the house, surrounded by the heavy presence of armed troopers for about 10 hours and were only able to leave in the morning.

Aitmaad and Sameer had borrowed Maqbool’s phone to call their families for their departing conversations.

A resident of Amishpore in Shopian, Aitmaad, in his late twenties, had joined the insurgents on Nov 5, 2017. His father, an apple farmer, says he had “lost a debate” about life and death with his son and couldn’t stop him from picking up arms. “I asked him to rethink about the path he chose. However, my son said he would return if I promised him he would never face the reality of death. I could not convince him,” his father was quoted in a news report. Aitmaad had returned to Kashmir after completing his MPhil in Urdu from Hyderabad University and wanted to pursue a PhD before he joined the militants. An undergraduate student, Sameer who is heard speaking to his parents and siblings in the recording, was a resident of Hillow village in Shopian and had joined the militants only a month before the encounter.

Over 200 people were injured in the protests and funeral processions that followed and several people were hit by pellets in their eyes. Maqbool’s house was completely destroyed. The morning saw remnants of a charred home and the dead.

SV: The nature of artefacts, archive, and memorialization are rapidly transforming in the age of WhatsApp. These dispatches from the encounter sites, as you argue, are widely downloaded and shared despite internet and digital crackdown. Can you tell us a little more about how these recordings have become a part of the Kashmiri collective consciousness and resistance?

UF: These recordings capture ordinary details of departing lives. These affective practices of speaking and listening, these intimate, mournful and poignant conversations are people’s archives and memorials constituting a counter-public. As opposed to the State’s fossilized, static and closed archives marked by colonial obsession, chronology, continuity and repressive erasure, these people’s archives rupture the statist continuity and challenge historiography. The strength of these people’s archives lies in their ephemerality and openness that offer critical possibilities. These recordings lie at the intersection of history and memory, they imbue both with new meanings and offer alternative imaginations of past, present and future.

In Kashmir, the State has exercised a monopoly over which lives are deemed grievable. It has thwarted funeral processions and funeral prayers, opened fire on mourners, delayed handing over of the dead to their families and sometimes denied it altogether (an open grave in Kashmir still awaits the mortal remains of both Mohammad Afzal Guru and Mohammad Maqbool Bhat who were sent to gallows in New Delhi’s fortified Tihar prison). Amid such clampdown, these recordings of the last phone calls are important conversations that allow people to mourn and enable the transformative possibilities of mourning. These recordings challenge the State’s efforts to deny people the parting words and accounts of their loved ones and the witnesses – Afzal Guru’s wife and son weren’t informed of his execution and were denied a last meeting. The callers – the insurgents – through these conversations claim the familial bond and trust which the State attempts to rupture. These conversations reinforce the trellis of support and care that nurtures the resistance in Kashmir, they transform the familial relations and imbue them with new meanings, creating a greater family, beyond blood ties: a network of solidarity, a human chain of witnesses and resistors.

While the State fosters mistrust and barbarity, these recordings and their dissemination reverses this process and forges compassion. It is this poignant force of compassion and resistance, compassion of resistance and compassion as resistance that the State is anxious about. A police officer, referring to these phone calls and their wide circulation, told the press: “It is a dangerous pointer. It shows how dying is being glorified by the parents themselves and the family support lent to trapped militants.”

While in many societies and cultures death and the dead remain a taboo, in Kashmir death, the dead and narratives of death are part of the everyday. In this sense, these audio recordings of the last phone calls invoke and cite a transformative eschatology allowing the family and friends and the larger circle of supporters to come to terms with their separation thus allowing a sense of continuity. These conversations cite death as a continuation or a transition. The transiency of life and the certainty of death are evoked, to define an ethicality of living. The callers bind their family and the listeners into an ethical-political engagement that constitutes them as ethically responsible beings. Families are reminded to settle their debts, forgiveness is sought for broken promises, while new promises are given and taken, reassurances of meeting again are pronounced, and the value of a life fighting oppression and falsehood is emphasized. These phone calls imbue a new meaning to closure. In these last moments of death, life is lived converging the power and promises of past, present and future. These fearless conversations reaffirm the certainty of death, but also reaffirm life. These narratives of death and departure are in fact narratives of life and arrival.

SV: The nature of unmitigated violence in Kashmir sometimes makes narrating this violence and its repetition difficult. Do you see new narrative forms of expression emerging?

UF: There are several layers to this question. In your first question you talk about the inadequacy of language in relation to the Holocaust. I think this is also relevant here.

Jean-Francois Lyotard compares Auschwitz to an “earthquake that destroys not only lives, buildings and objects but also the instruments used to measure earthquakes directly or indirectly.” He further notes: “The impossibility of quantitatively measuring it does not prohibit, but rather inspires in the minds of the survivors the idea of a very great seismic force”. Prompting considerable debate, Theodor Adorno wrote: “To write poetry after Auschwitz is barbaric,” which he later retracted by saying: “Perennial suffering has as much right to expression as a tortured man has to scream; hence it may have been wrong to say that after Auschwitz you could no longer write poems.” Though one must be critical of dividing the history into before and after Holocaust and challenge its centrality to history writing without diminishing the horror of violence and persecution (of not only Jews but other minorities as well, like the Sinti and Roma), I think Adorno’s statement and his later retraction and Lyotard’s reflection point out to the inadequacy and limits of language, the unspeakability, the impossibility of narration in such circumstances. However, in some sense, it is the “great seismic force” of unquantifiable and unfathomable unspeakability that eventually displaces the ground of impossibility, consuming it in its own force – making the ‘scream’ possible.

Even though poetry was written during and after the Holocaust and continues to be written amid utmost barbarity— in the cells of Guantanamo, amid airstrikes in Syria, under siege in Palestine, massacres in Kashmir, lynching in India, and several other ‘nameless’ places which haunt the dominant history and history writing practices – impossibility as a motif is a profound marker of such narrations. Such work employs self-referentiality and points to its own impossibility.

For example, in Poems from Guantanamo, Sami Al Haj, a Sudanese journalist who was covering the war in Afghanistan in 2001 and was tortured at Bagram air base and Kandahar before he was shifted to Gauntanamo, writes in one of his poems:

I was humiliated in the shackles

How can I now compose verses?

How can I now write? After the shackles and the nights and the suffering and the tears,

How can I write poetry?

Similarly, Abdulla Majid Al Noaimi — a citizen of Bahrain who after an unsuccessful search for a missing family member in Afghanistan made his way to the Pakistani border where he asked the authorities that he be taken to the Bahrain embassy but instead the Pakistani authorities turned him over to the U.S military— writes in one of his poems collected in Poems from Guantanamo:

So I set out to write but I could not concentrate on the poem. I put poetry writing aside and turned to memorising the Quran. But then I could not concentrate on the Quran, because my mind was occupied with the poem. With my mind divided, time began to pass. And then I was inspired: My heart was wounded by the strangeness

Now poetry has rolled up his sleeves, showing a long arm

These haunting poems from Guantanamo emerge from, as Ariel Dorfman writes in the epilogue to the book, “the simple, almost primeval, arithmetic of breathing in and breathing out”. In Kashmir too, the source of these narratives is a fierce sense of hope and survival, and these are chronicles of the impossible “arithmetic of breathing in and breathing out”, even though the conditions for breathing (both literally and figuratively) are made impossible, unthinkable.

In Kashmir the State’s war on people manifests itself not only as a direct military control but as a systematic, ideological war; a cultural war, a war of narratives and words, a war waged to control desires, choices and wills, bodies, resources and land. Understanding violence, unpacking its knowability and unknowability is an uphill struggle. More so when the nature of such violence, as you point out, is repetitive and unmitigated, marked by a constant and repeated inscribing and re-inscribing. Incomprehensibility and unspeakability in relation to loss are intense experiences, sometimes exceeding or amplifying the intensity of loss itself. In addition to these quandaries and the enormity of violence, the state’s efforts in Kashmir are also aimed at systematically destroying the instruments to measure violence, co-opt the mechanisms of resistance, seize and destroy language, impose a narrative control, gag and exhaust the witness. It is a State that kills, blinds and maims, that uses torture and rape as weapons of war and organizes art camps “nurturing cultural heritage and identifying young talent, exposing youth to modern and contemporary art.” It is a State that portrays itself as a champion of women empowerment and organizes motivational talks and psychological and counselling programs. This militaristic humanism has been vital to its war on people.

The State’s stringent narrative warfare that aimed at perception management and public relations is a whitewashing tactic. In this enterprise of narrative warfare, repetition has been a systemic strategy of the occupying regime’s war on people. In the manual of oppression and the templates of violence, repetition is a structural force. Life and death have been subjected to brutal repetition in Kashmir. India’s oft-repeated question What do Kashmiris want? is not merely a buying-time tactic or an entrapment, but it is indicative of how the occupying State exercises repetition as a tool of its sustenance.

The efforts of people’s resistance in Kashmir, on the other hand, have been directed towards retrieving the singularity of every such act of violence. The resistance and its narratives in Kashmir have limned and pointed to a distinct home, a distinct room, a wall, a street, a window, a bullet, a grave, a tree, a body, an eye, a limb, a bone, a life. And at the same time these singular narratives have been strung together into a resonance. In the wake of the State’s homogenizing brutality, its repeated violence and the exhaustion it imposes, the challenge has been to not lose the criticality of this singularity. People’s resistance in Kashmir has reclaimed repetition and used it as a liberatory practice to foster a multiplicity of voices and resonance.

The emerging narrative forms are in a continuum with the rich repertoires of resistance that have existed in Kashmir. These grassroots narratives have employed visuality, aurality and orality encoding resistance into cultural memory. Everyday practices and projects of memory and memorialization are integral to these repertories. The strength of these narratives also lies in their radical lack of closure amid a perpetual war.

In Kashmir, as violence is constantly inscribed on bodies, landscapes, homes and streets, skies and earth, resistance too writes itself over these same sites turning them into critical notions of justice and liberation, into sites of and for narratives rooted in people’s memory. Every home is a memorial, an address of loss, a story of survival. These transformative and restorative narrative practices challenge the State’s narrative warfare.

Language too is one such sites, which shapes and is shaped by people’s experiences and memories of oppression and resistance. In this sense, language not only is a carrier of narratives, but it is a narrative in itself. Silence – as a formal interlude and as a technique in people’s narratives and as an everyday articulation – is one of repertoires of resistance in Kashmir. This silence, redefined beyond the contours of absence and passivity and capturing both the limits of language and the intense force of unspeakability, is agential in its myriad meanings.

Even though narrative forms emerging from Kashmir could be read and discussed within the framework of aesthetics, their strength lies in telling truth to power amid widespread persecution and systemic violence. They inform and are informed by a powerful aesthetics of loss, survival, hope, subversion and resistance.

SUPPORT US

We like bringing the stories that don’t get told to you. For that, we need your support. However small, we would appreciate it.