Learning the Ropes of the Ram Rajya: How the children of Bihar are taught religious hatred

On his way from the playground discussing Friday prayers with his brother, an 11-year-old boy was taking the same route he took every day, when another boy on a cycle, only a few years older than him, stopped right in front of him and slapped him. “You are a Muslim,” the 11-year-old recounted what the older boy had said. “I’ll hit you more if I ever see you in the Brahmin colony.”

The 11-year-old and his brother did not retaliate. They both knew the older boy was from the Brahmin colony, just 500 metres from their own neighbourhood, both located in Araria district, in eastern Bihar’s Seemanchal region. They knew that when the incident occurred, they were neither near the Brahmin neighbourhood at the time, nor returning from a playground there, nor would they pass through it on their way to the mosque. They knew they had not done anything to provoke the slap. They did not retaliate because it was 22 January, and while they did not know what heightened tensions a retaliation may have triggered, they did not want to find out. They just stood on the spot, aghast and afraid, as the older boy drove away on his cycle.

Araria is one of few districts in India’s Hindi belt where the margin of the Hindu majority is slim, with Hindus constituting 56 percent of the district and the Muslims comprising 43 percent, according to the census of 2011. Yet, on that day, Hindu supremacist rallies swarmed the district, celebrating the long-awaited consecration of the Ram Temple in Ayodhya. The temple was inaugurated while under construction—ostensibly bearing in mind the electoral dividends it promises for the general elections this year—over three decades after the demolition of the Babri Masjid that once stood in its place. The demolition marked the violent peak of the Ram Janmabhoomi movement, which claimed that the 16th century mosque was built after destroying a temple at the birthplace of the Hindu deity Ram.

Led by the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh, the fountainhead of Hindu nationalism in India, and its political wing, the Bharatiya Janata Party, the Ram Janmabhoomi movement has long sought the erection of a temple at the site in Ayodhya. Unsurprisingly, its consecration was an epochal moment in the Hindu nationalist movement and the prime ministership of Narendra Modi. In his speech, Modi made thinly veiled remarks about the temple’s significance in the establishment of a Hindu Rashtra—a Hindu nation. “We have to expand our consciousness from deity to nation, from Ram to rashtra,” he declared.

On 22 January, the nation rejoiced in the construction of a temple at the site of a demolished mosque. Loud chants of “Jai Shri Ram”—Hail Lord Ram—could be heard across the country. In answer to Modi’s call to celebrate the day as Diwali—the mythological festival that marks the return of Ram to his homeland—cities across India were lit up with diyas and decorated with saffron flags, swastikas, bows and arrows. Weeks after the consecration, the BJP passed a resolution declaring that the temple “heralds the establishment of Ram Rajya in India for the next 1,000 years.”

For Muslim children in Seemanchal, this Ram Rajya began with a new, brazen hostility. We spoke to over a dozen children from the region—both Hindus and Muslims, all below the age of 14, and from low-income families of daily-wage labourers or small farmers—and observed this sentiment across the conversations. (We are choosing not to disclose their identities at the request of their parents and to protect the children from repercussions.) The hostility was most often reflected in aggressive remarks, targeted towards not just Muslim children, but even teachers. While the Ram Mandir led to a new, unabashed religious intolerance among children, surrounding factors played a crucial role, especially a parallel rise in polarising videos. The effect was a distinct feeling of alienation from even those whom they considered friends. “Santosh chacha’s son told me that when the doomsday comes, all Muslims will be driven away and all mosques will be replaced by temples,” the 11-year-old said, referring to a friend in his own neighbourhood. “Next, it’s the turn of the Taj Mahal.”

The significance of the Ram Mandir consecration in contemporary Indian politics cannot be understated. The attendees included RSS chief Mohan Bhagwat, and leading figures from the film and cricket industry including Amitabh Bachchan, Ranbir Kapoor, Alia Bhatt, Sachin Tendulkar, and Rajnikanth. “It seemed like the day of foundation for a Hindu Rashtra,” said Bhanwar Megwanshi, a Dalit activist and author who wrote a memoir, I Could Not Be Hindu, about quitting the RSS upon recognising the pervasive Brahminism within the Sangh. “It has to be acknowledged that in the last 100 years, RSS has never received as much recognition as it did on this day.”

For the children of Seemanchal, too, it was an important day, even if they did not understand the politics behind it. The Hindu children shared how the consecration ceremony was celebrated with joy and festivities at par with Diwali. For the Muslim children, on the other hand, the day was a sombre occasion at home. Two 12-year-old boys from the Araria town recalled how their families and other Muslim households in their neighbourhood observed a fast on the day. One of them noted that nobody on the live telecast of the consecration ceremony was Muslim. “It felt very alienating as we thought that no one stood with us,” one of them said. “My mother didn’t let me go out to play or use the phone that day.”

The other 12-year-old had gone to the market with his mother that day. He described seeing a group of boys walking around carrying saffron flags in their hands and playing loud Hindutva songs. “It seemed as if they had come to fight,” the 12-year-old said. “If there were some older Muslim boys there, then there would have been a fight.” He remembered the day vividly. “The whole street was filled with such flags. The police were standing right there but they didn’t do anything about the loud music. Later after some time, I saw that the police vehicle also had the same saffron flag on it.” (A police car with a Jai Shri Ram sticker was recently reported in Patna.)

In the Hindu children’s memory of the day, too, the alienation of Muslims featured prominently. An 11-year-old from Narpatganj town, in Araria district, said the inauguration ceremony was celebrated in his village with a feast. “While we were having food, I saw a few Muslims come to join us but they were asked to run away.” Another 11-year-old from Seemanchal’s Katihar city recalled how his village had organised a DJ to celebrate the ceremony, who played communal music despite ongoing tensions between his neighbourhood and a nearby Muslim neighbourhood. A 13-year-old from Araria town, who was otherwise shy and reserved, broke into song, “Awadh mein gao khoob badhai, ghadi mandir banne ki aayi”—Sing praises in Ayodhya as it is time to build the Ram temple. The 13-year-old added, “Muslims should be thrown out of the nation because they have their own country.”

All children appeared to unconsciously adopt such popular polarising narratives. One 12-year-old from Katihar expressed these anti-Muslim sentiments despite hailing from the Santhal tribe, and as such being outside the Hindu fold. His community worships the local deity Lankhi Mata during the harvest season and the goddess Kaali on Diwali. The 12-year-old had not even seen an idol of Ram in his village, and yet, joined his village in lighting diyas on 22 January to celebrate the consecration ceremony. “Muslims are considered bad people in our village because people say they eat cow meat,” he said.

In stark contrast to the boys, the girls we spoke to appeared to have very basic information about the Ram Temple, and did not reflect the same communal sentiments. Our conversations suggested two primary reasons for this: firstly, the gendered nature of household work resulted in the girls usually being occupied with chores at home after school, whereas the boys were freer to be social and unobserved. Secondly, and consequently, the girls had lesser access to mobile phones, while the boys were regularly using the phones of their family members, which seemed to be one of the strongest influences of the growing religious intolerance among children.

Education through YouTube Shorts

The brazen hostility among children witnessed in the weeks surrounding the Ram Mandir consecration was a new phenomenon. One explanation to emerge from the reporting was the internet consumption by the children, and the staggering popularity of hateful videos that the children began watching at a young age. The children had gained increasing access to use their family’s mobile phones during the pandemic, with the teaching conducted online, which simultaneously led to greater comfort with navigating the internet. That year, YouTube launched its Shorts section in India, which quickly became a favourite among the children. The primary form of entertainment for the children of the Seemanchal region were YouTube Shorts, Instagram reels and pop music videos, all of which presented distorted and over-simplified versions of history, each with an undercurrent of Hindu nationalist pride.

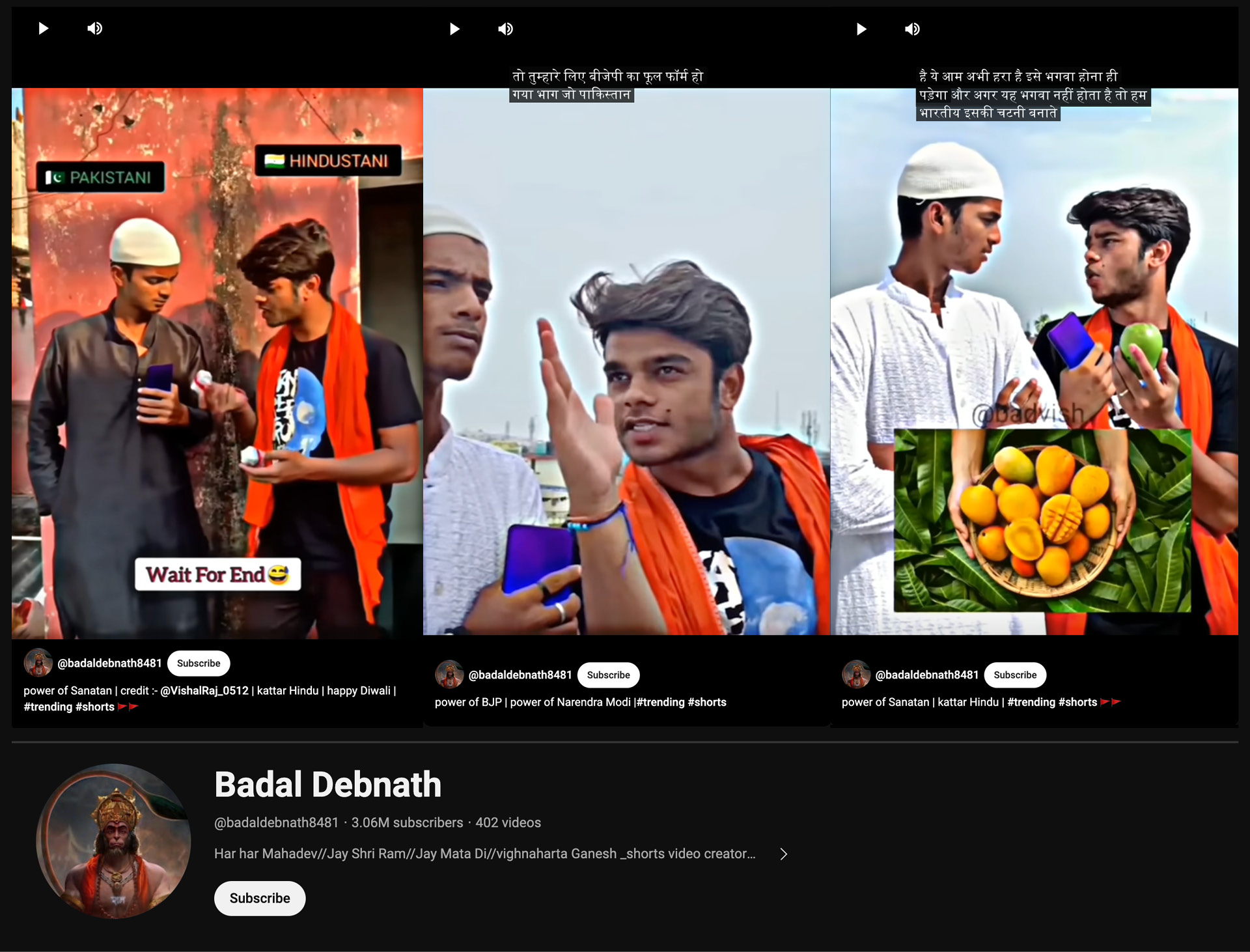

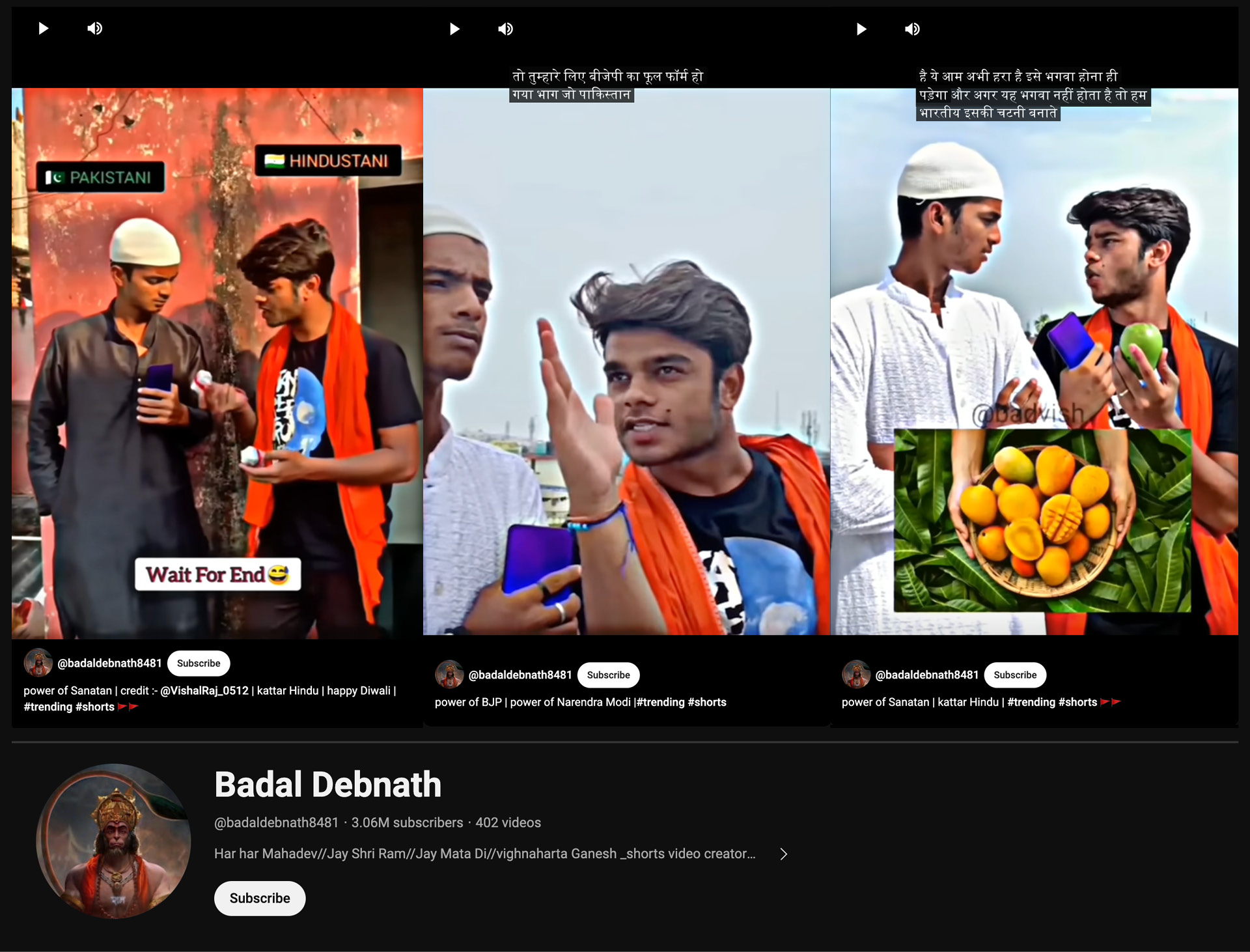

One 11-year-old from Narpatganj confessed to being hooked to YouTube Shorts of Hindu-Muslim clashes. He described one of his favourite videos with great excitement, repeating each line verbatim. “There is one video where one boy represents India and another boy in Muslim attire represents Pakistan, and the Hindu boy tells the Muslim boy, “Jitne tumhare yahan sainik hain, utne toh hamare yahan kaidi hain, shaam ko kaidi ki rehayi aur subah Pakistan ki safai.” (We have as many prisoners as you have army men. We will release our prisoners in the evening and by morning the entire Pakistan will be cleaned out.)

All the children we interviewed had watched such short videos with India-Pakistan representations, which invariably created an image in the children’s minds that anyone who wears a skull cap and a kurta-pyjama is a Muslim, and therefore, a Pakistani. Meanwhile, someone who wears a tilak and a saffron-coloured cloth around their neck becomes a “Hindustani.” The video described by the 11-year-old from Narpatganj had over 1.3 crore views.

Two YouTube channels that repeatedly came up in our conversations were Badal Debnath and Rahul indian boy, who had over 30 lakh and 8.5 lakh subscribers respectively, at the time of publishing. Even a cursory look at these channels reveals communal, misogynistic and hateful content. For instance, Rahul indian boy’s videos frequently showed Muslims as terrorists, often beating up an Indian army man. The videos were often violent, and included child actors dressed up as soldiers wearing skull caps, and acting out scenes of brutal murders of Indian soldiers with knives and rifles. The general tone and aim of the videos seemed to invoke patriotic fervour.

On the other hand, Badal Debnath channel compiles videos from different channels with a running theme of Hindu supremacy over Muslims, and generally pertain to Indian politics. Vishal Raj is a creator whose videos frequent the channel and are among its most popular. In most of Raj’s videos, the word “Pakistani” is often written above the Muslim character, played by a Hindu actor, and “Hindustani” above the Hindu characters. In one video, the Hindu character comes to the Muslim character and says, “There is good news for you and there is sad news. The good news is that the Ram temple has been built, the sad news is that now it is the turn of Kashi Mathura.” In another video, which has 4.5 crore views, a Muslim character says, “Brother, look, even the colour of mango is green.” The Hindu character responds, “It is green right now but it will have to turn saffron. If it doesn’t, then we Indians make chutney out of it.”

The Badal Debnath channel has uploaded over 380 videos since its launch in February 2023, all in the YouTube Shorts section, launched by the platform in September 2020. The channel’s early videos were edited clips of speeches by Modi and Dhirendra Krishna Shastri, a self-styled godman popularly known as Bageshwar Dham Sarkar. The Badal Debnath channel started posting Raj’s videos last June, which grew increasingly popular, and by August, one of the videos had received over 35 lakh views. In it, a boy in Muslim attire asks a Hindu boy, “What is the full form of BJP?” The Hindu boy replies, “The full form is Bharatiya Janata Party, but if you have a problem with BJP, then for people like you, it is Bhag Jao Pakistan.’” In the last eight months, the channel uploaded several videos by Raj targeting Muslims and asserting Hindu dominance.

On 30 September, the channel uploaded a video on the demolition of a mosque and the construction of a temple on the same site. The Hindu character then declares that even if the Muslim character produces documents to establish its title over the property, the records can be changed in parliament. The video received around 54 lakh views. It was among the channel’s most-viewed videos posted till then, and its subsequent Shorts focused more on the Hindu-Muslim divide and videos related to Hindu supremacy, which received high engagement.

Raj is an aspiring actor and dancer from Patna. Around one year ago, the 20-year-old teamed up with two friends, Aarav and Sahil, and started making sketch-comedy videos, some of which focused on Hindu supremacy, to post on their Instagram page, “badvish_.” He discovered that his communal videos were an instant hit. “Our first such video roasting Muslims was on the film The Kerala Story, which went viral and garnered 1 crore views,” Raj told us. “After that we realised how much people enjoy such videos so we kept making them.” He also mentioned that his Instagram page which had 96000 followers was removed by the platform but he made another page with the handle “_badvish_al,” and continues to post videos from it. Raj said that his family has tried to dissuade him from making videos targeting Muslims. “We don’t have any ill-intent towards the Muslim community, but our videos do well when we roast Muslims so we keep making these videos,” he added.

On the other hand, Raj was vocal about his support for the BJP and its authoritarian Hindutva politics. In reference to one of his videos about the Enforcement Directorate dropping cases against opposition politicians once they join the BJP, he said, “We enjoy the bulldozer politics and ED raids on opposition leaders.” Raj has even tried making a few videos on Hindu-Muslim unity but he said that his viewers widely criticised him for it. “They simply don’t work,” he said. “People start questioning our intent and troll us so we stick to roasting Abdul videos.”

Despite the highly political content of their videos, and even claiming to have received words of encouragement and promise of support from a local BJP leader on Instagram, Raj is uninterested in joining politics. He is currently in his second year of a Bachelor of Arts programme in a Patna college, but his dream is to break into the South Indian movie industry. He spends much of his time travelling through Uttar Pradesh and Bihar for small acting and dancing assignments. “I don’t want to be an Instagrammer or a Youtuber,” he said. “I’ll quit these platforms once I complete my studies and join the National School of Drama.”

Raj gave little thought to the impact of his videos on children. He acknowledged that the analytics of their Instagram channel had revealed that viewers in their early teens were their most popular demographic. Yet, he appeared surprised when informed that his videos were shaping the ideas of religion and communities for the young boys of Seemanchal. “I don’t know if I should feel happy or sad about this,” he said.

The Hindu children of Seemanchal all said the algorithm recommended Shorts from these channels, and that they enjoyed them because the videos were entertaining and instilled a sense of nationalistic pride. These videos were usually produced in a standardised format, with high-paced soundtracks and memes that disguised their hateful content as laughable entertainment. The format was efficient, given that the children all chuckled as they recalled the videos.

The Muslim children had seen the videos as well. The 12-year-old from Araria spoke about how the videos “make fun of my community and my God.” One video that stayed with him is one where the Hindu character complains to the Muslim character that a firecracker he bought does not burst, and asks him how he does it. The Muslim responds by demonstrating—he chants “Allahu Akbar”—God is great—and throws the firecracker, which immediately bursts. He then tells the Hindu character, “Do you see? The bomb blasts only after you say, ‘Allahu Akbar.’” The Hindu character asks him to repeat it, and then throws a cracker at him. At the time of publishing, this video had a staggering 3.8 crore views, 15 lakh likes and over 16,000 comments.

The most popular videos among the Muslim children also had heavy religious undertones, though they did not demonise the Hindu community. They primarily revolved around Islamic customs and the significance of being a good Muslim. In one video with over 2.4 crores views, by the channel “Insta team 0009,” which has 22.7 lakh subscribers, a milkman who swears falsely on Allah loses his tongue. “Mansoor official_22” is another popular channel with 97 lakh subscribers. In his second-most watched video, with over nine crore views, a Hindu boy returns a piggy bank lost by his Muslim neighbour, noting that money has no religion. Another video with over 89 lakh views compares two kinds of Muslims, one who goes to a public school and another who goes to a Madarsa, and ultimately shows how the latter is the better Muslim.

Bhojpuri Hindutva pop music also has a large viewership among boys in Bihar. These songs are repeatedly blared during rallies and processions by Hindu supremacist groups across the state. Songs such as “Har ghar bhagwa chhayega, Ram Rajya ab aayega” (Every house will be coloured in saffron and the rule of Ram will now come) and “Bharat ka baccha baccha Jai Shree Ram bolega (Every child of India will chant Jai Shree Ram) have replaced mainstream pop music in India’s hinterland. These songs, too, have gained in popularity amid the Ram Mandir celebrations, with new singers and musicians entering the fray. The songs often call upon Hindus to transform the nation into a Ram Rajya, and to wake up and point their swords at their enemies. The songs have viewership going into the millions.

Kunal Purohit, who recently wrote the book, H-Pop: The Secretive World of Hindutva Pop Stars, spoke to us about the youth audience of these musicians. “One of the insights my characters, the Popstars, would often lend me is that the young were a very crucial audience for them,” Purohit said. “In events that I attended with some of them, the young were integral and visibly active participants. However, I wouldn’t necessarily categorise them as children, but possibly in their teens/late teens and young adulthood. However, in Ram Navami rallies or in processions that were often brought out or supported by Hindu right-wing organisations, I spotted children playing an active role and, often, singing along to Hindutva pop songs that were being played by the DJ. This was something that was not restricted to rural, semi-rural areas but a phenomenon that I noticed in the heart of Mumbai.”

Purohit said that at its core, the popularity of H-Pop lay in its simplification of complex issues in a format that created easy, convenient narratives and opinions, for an audience that is not inclined to grapple with the nuances involved. “H-Pop captures them young and early and sets narratives about such characters and events so that they leave deep imprints on young minds,” he said.

Shifa Haq, an assistant professor of psychology-psychotherapy at the School of Human Studies at Ambedkar University, Delhi, spoke about the impact that such videos and interactions could have on children. “They negotiate feelings of love and attachment, sadness and insecurities,” Haq said. “If the outside environment is so hostile and overwhelming, not only do they not get help to cope with their complex feelings, they might repeat experiences of hate or be hated by scrolling through hate-filled short videos or messages that validate their feelings but do not offer any way out. This might keep them trapped, or give a fantasy of mastery in a provocative environment.”

AltEd is an activity-based initiative on media and information literacy curriculum for kids aged 12-14, which works with seven schools in and around Kolkata, and conducts focus-group discussions with the school children. A team member of AltEd, who requested to remain anonymous, shared insights on the trends of internet usage among children. They shared that during AltEd’s focus groups, the children unanimously admitted to using their phones throughout the day, and primarily during meals and tuitions. “Largely, we saw that the time children spend on phones is enormous and cuts across different income groups,” the team member said. “YouTube and WhatsApp are the two apps that children use the most. Between social media platforms, YouTube remains the most watched platform and they share the links from YouTube the most.”

The team member noted that the more surprising detail they discovered was that the way children verify the information shared in a particular short video was to go into the comment section. If a large number of people supported the video, they believe it to be true as well. “YouTube is designed infrastructurally to give you the content and also gives you a mechanism to verify it,” the team member said. “It’s deeply concerning to think that children believe that the mechanism to verify facts is built within the platform. They don’t have to look anywhere outside of that.”

By all metrics, YouTube consumption in India is significant. According to a 2024 report co-published by the Federation of Indian Chambers of Commerce and Industry and Ernst & Young, Indians alone constitute over 18 percent of YouTube users, with nearly 467 million monthly users. It is not only the largest online platform in India, it has even surpassed television in Bihar and Jharkhand. The FICCI-EY report further revealed that YouTube is the most preferred social-media platform for news consumption. At Google India’s Brandcast 2023 event in September last year, the tech giant revealed that YouTube Shorts’ average daily views grew by 120% year-on-year. Another report found that India spent 6.1 trillion minutes watching online videos between January 2022 and March 2023, 88 percent of which was on YouTube.

Purohit argued that platforms such as YouTube do little to combat the spread of misinformation, communal tensions and religious bias propagated in these videos, and instead serve to not just help these artists survive, but flourish. “These platforms have actively aided, by way of funding the creation of content that, sometimes, incites violence and stokes anger and fear against minorities and critics,” he said. “Thanks to the monetisation that platforms like YouTube as well as audio-streaming platforms offer, such creators get a continuous, and lucrative stream of income that allows them to continue making such hateful content.”

YouTube’s policies sound earnest on paper. It claims to fight misinformation, curb extremist content, and prevent bias, among other things. It also has a three-strike policy where the first strike can freeze an account for a week, the second strike freezes an account for two weeks and the third consecutive strike will result in the termination of a channel. “We’ve heavily invested in our policies and systems to successfully combat hate speech, and harmful and dangerous content on YouTube,” a spokesperson told us.

However, despite the videos containing misinformation about the country’s historical facts, hate-mongering and extremism are being peddled on the platform without justified consequences. Sandeep Acharya, a member of the Hindu extremist group Hindu Yuva Vahini, has openly spoken about how he circumvents YouTube’s policy. “According to their terms and conditions, it is hate speech,” he told the German public broadcaster Deutsche Welle. “A lot of my channels are suspended. But our reach is very high on the platform, so once a channel is taken down, I make another.” The YouTube spokesperson identified different channels and videos by Acharya that had been removed, including those posted by other channels such as Mayur Music and Janta Musical and Pictures. However, several videos of Acharya posted by the latter were still in wide circulation, including one titled, “Kisi Ke Bap Ki Nhi Ayodhya”—Ayodhya does not belong to anyone’s father—with 13 million views, containing clear divisive, anti-Muslim undertones, and posted in 2018.

In a written response, the YouTube spokesperson responded to queries with generic statements about their Community Guidelines policy, which sometimes raised further questions. The spokesperson listed out the policy against hate speech, dangerous or illegal activities, and violent or graphic content, as well as the thousands of channels and videos removed globally for violating these policies. According to Google’s Transparency Report for the last quarter of 2023, the platform removed over 2.25 million videos from India—the highest across the world. The spokesperson also noted that sometimes, “content that would otherwise violate our Community Guidelines may stay on YouTube when it has Educational, Documentary, Scientific, or Artistic (EDSA) context.”

The spokesperson said that YouTube had removed one video by the channel Rahul indian boy “for violating our harmful and dangerous policies.” It was not one of the violent videos flagged by us to them, and the channel remains active with numerous graphic videos of child actors depicting religious violence. The spokesperson did not respond to repeated follow-up queries about whether other videos by the Rahul indian boy channel and the Badal Debnath channel did not violate the guidelines, or if it had received an EDSA exception.

Religious discrimination in schools

The schools in Seemanchal, too, struggle to remain secular spaces. A school principal of one of Purnea’s biggest private schools, who requested to remain anonymous out of fear of backlash, shared that the socio-political climate of the country impacts the school environment as well. “We consciously ensure that we don’t let the communal tension enter academic spaces,” the principal said. Yet, even the school faculty were not spared the communal bullying.

“In one incident, a Muslim teacher was targeted by some students of class eighth who raised slogans of ‘Jai Shree Ram’ whenever he was around,” the principal recalled. “There have been some more incidents like this, so we try to talk to students and tell them that school is not a place for such slogans.” A history teacher in the school said she had been similarly targeted for her Muslim identity. “They acted like a mob loudly chanting ‘Jai Shree Ram,’ so I asked them whether this act of theirs will make Lord Ram happy,” the teacher said. “They responded saying that I’m only saying this because I’m a Muslim.”

However, while the principal expressed concerns about the growing religious intolerance among the students, the secular practices of the school are debatable. Within its premises, there is a temple for the Hindu goddess of knowledge, Saraswati. But the principal asserted that it was a secular institution that sought to celebrate all religious festivals harmoniously. “Our Muslim students have two periods off on Fridays for their prayers,” he said. “We celebrate Saraswati puja annually, and last year, we had a Muslim student lead the puja along with the priest.”

The principal noted that while he had not spoken to the Muslim student about the puja personally, “I am sure that our school would never force children into doing anything forcefully.” He added, “I wish we could celebrate Muslim festivals with the same rigour as we celebrate Hindu festivals but the political climate isn’t conducive to do so right now.”

The Purnea school is not alone in conducting Saraswati puja within the premises. Gauri Sharma, a principal of a government school in Araria, similarly told us that while they do not discriminate between children on religious identity, the school performs Saraswati puja every year.

According to the educationist Devyani Bhardwaj, for an efficient learning experience, Indian schools and curricula adopt context-based education, which allows children to bring the values of their home and community into the classroom. “However, if a teacher who is not properly trained, has certain social biases against a community’s customs, food habits and history, then these contexts are prone to be misinterpreted,” Bhardwaj added.

This was reflected in the teachings surrounding the Ram Mandir consecration within schools in Seemanchal. The 11-year-old from Narpatganj recalled the classroom discussions on 22 January: “Mere school mein ek teacher keh rahe the ki ab Hindu ka jaat badhta jayega aur Muslim ka jaat neecha girte jayega”—A teacher in my school said that now the status of Hindus will grow while that of the Muslims will decline.

The concept of the “hidden curriculum,” as coined by the American-Canadian scholar and cultural critic Henry Giroux also helps understand these practices in schools, and its impact on the students. According to Giroux, the hidden curriculum is the “unstated norms, values and beliefs transmitted to students through the underlying structures of schooling.” More simply put, as explained by Shaima Amatullah, a researcher at National Institute of Advanced Studies, it is the environment within the school beyond academics. This includes how a teacher talks to students, what kind of culture and rituals are followed in the school, how chapters around religious subjects are taught, all of which come together to form the experience of a student.

Amatullah believed that the hidden curriculum plays a crucial role in the actual curriculum—in fact, Giroux argued that students learn more from the former than the latter. “Oftentimes, the hidden curriculum is so normalised in schools’ overall atmosphere that subtle discriminations based on religion, gender, caste, class etc. don’t even come up for debate,” she said. “These routine practices mirror practices of the majoritarian group while excluding minorities and thus creating ‘the other’. To prove that the Muslim child has imbibed secular values, s/he needs to join the religious practices at the school while the Hindu child’s secular identity is never challenged.”

RK Yadav, a former social science teacher at a Kendriya Vidyalaya in Araria district, who retired in 2023 after two decades in service, emphasised that the teachers’ personal social and political ideology must not be delivered to the students. “Unfortunately, some teachers don’t adhere to this philosophy and let their personal views colour children’s minds as well,” Yadav added.

In this context too, the digital age has a major impact on the school experience. The history teacher from Purnea, noted the impact of the polarising media consumed by the students. “Previously there were discussions and debates in the classes, but now they speak whatever they listen on social media without verifying the factual basis of the information,” she said. “We are going through an acute educational crisis where the source of information for children is either YouTube or some WhatsApp forward. Recently, a student from my class told me he doesn’t like Gandhi because he begged from the Britishers. I’ve had students in my class who dissented against studying the Mughal Era, it’s bizarre.”

Not just the hidden curriculum, though, even the prescribed academic curriculum reinforces Hindutva narratives of history and society. Textbooks have long been a site of political contest in India, and the most recent edits point to a concerted effort to push the agenda of the Hindu nationalist ideology. In recent years, there have been significant revisions in the sections pertaining to the Mughal Era, the 2002 Gujarat pogrom and the caste system, with the most recent revisions concerning the section on the Ayodhya dispute in the NCERT’s Class XII political science textbook. The chapter spotlights the Ram Janmabhoomi movement and the Supreme Court verdict allowing the construction of the temple, while deleting at least three references to the demolition of the Babri Masjid that stood in its place.

It is important to also note how this religious radicalisation could impact various aspects of their lives growing up. Rachana Johari, a former professor at Ambedkar University whose research focused on psychology and gender, observed that due to the politics of religious polarisation, a sharp division of self and others starts forming in children, due to which they start developing stereotypes for various social categories. “They also learn that power and inequality is an integral part of the social structure,” Johri added. “If they have to control someone, then they should not control them with love, but by bullying or dehumanising them. They will do all this with the individuals or groups who do not form part of their self identity.”

On the other hand, the child psychologist Kalpana Purushottaman, who works with children in conflict with the law, noted that children from minority communities become so habituated to being attacked, threatened, or stereotyped, that their trauma response in any conversation is to be defensive. “On the other hand, children from dominant communities use their power and privilege to release their pent-up frustration on those coming from oppressed communities and are safe to hate,” she added. “As a society, we have created a scapegoat amongst Muslims.”

The constant bullying and harassment of children based on their Muslim identity can also lead to a responsive radicalisation. “This politics of hatred is also turning Muslim children against Hindus as well,” the social activist Shabnam Hashmi said. “Basically, children who develop this mindset don’t grow up to be humane human beings, but harbour violence and ultimately this violence will come out on everyone who they consider inferior to them including women.” Purushottaman reiterated this point, noting overt radicalisation reinforces misogyny and patriarchy in the society. “If the radicalisation is coming from children, it means that the younger generation is becoming even more conservative and patriarchal,” she added.

The old proverb “shared joy is double joy; shared sorrow is half a sorrow” loses meaning in the Ram Rajya, when the joy of the construction of a temple lies in the sorrow of the demolished mosque that stood in its place. While Hindu nationalism is much older than both the consecration of January 22 or even the Ram Janmabhoomi movement, the scale and vitriol of its penetration among children is a recent phenomenon. The children of Seemanchal have not been passive observers to this shift, but victims of religious hatred and alienation, taught by society to take joy in each other’s sorrows.

“I felt happy and excited by the happiness of the Hindus when they take out processions of Bol Bam or in celebration of the temple being built,” the 11-year-old from Araria town said. “But they say that now only Hindus can live in this area, it is hurtful.”

Editor’s Note: This article has been updated following an additional statement by YouTube, issued after the piece was published, about its actions concerning videos by Sandeep Acharya and the “Rahul indian boy” channel.

Related Posts

Learning the Ropes of the Ram Rajya: How the children of Bihar are taught religious hatred

On his way from the playground discussing Friday prayers with his brother, an 11-year-old boy was taking the same route he took every day, when another boy on a cycle, only a few years older than him, stopped right in front of him and slapped him. “You are a Muslim,” the 11-year-old recounted what the older boy had said. “I’ll hit you more if I ever see you in the Brahmin colony.”

The 11-year-old and his brother did not retaliate. They both knew the older boy was from the Brahmin colony, just 500 metres from their own neighbourhood, both located in Araria district, in eastern Bihar’s Seemanchal region. They knew that when the incident occurred, they were neither near the Brahmin neighbourhood at the time, nor returning from a playground there, nor would they pass through it on their way to the mosque. They knew they had not done anything to provoke the slap. They did not retaliate because it was 22 January, and while they did not know what heightened tensions a retaliation may have triggered, they did not want to find out. They just stood on the spot, aghast and afraid, as the older boy drove away on his cycle.

Araria is one of few districts in India’s Hindi belt where the margin of the Hindu majority is slim, with Hindus constituting 56 percent of the district and the Muslims comprising 43 percent, according to the census of 2011. Yet, on that day, Hindu supremacist rallies swarmed the district, celebrating the long-awaited consecration of the Ram Temple in Ayodhya. The temple was inaugurated while under construction—ostensibly bearing in mind the electoral dividends it promises for the general elections this year—over three decades after the demolition of the Babri Masjid that once stood in its place. The demolition marked the violent peak of the Ram Janmabhoomi movement, which claimed that the 16th century mosque was built after destroying a temple at the birthplace of the Hindu deity Ram.

Led by the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh, the fountainhead of Hindu nationalism in India, and its political wing, the Bharatiya Janata Party, the Ram Janmabhoomi movement has long sought the erection of a temple at the site in Ayodhya. Unsurprisingly, its consecration was an epochal moment in the Hindu nationalist movement and the prime ministership of Narendra Modi. In his speech, Modi made thinly veiled remarks about the temple’s significance in the establishment of a Hindu Rashtra—a Hindu nation. “We have to expand our consciousness from deity to nation, from Ram to rashtra,” he declared.

On 22 January, the nation rejoiced in the construction of a temple at the site of a demolished mosque. Loud chants of “Jai Shri Ram”—Hail Lord Ram—could be heard across the country. In answer to Modi’s call to celebrate the day as Diwali—the mythological festival that marks the return of Ram to his homeland—cities across India were lit up with diyas and decorated with saffron flags, swastikas, bows and arrows. Weeks after the consecration, the BJP passed a resolution declaring that the temple “heralds the establishment of Ram Rajya in India for the next 1,000 years.”

For Muslim children in Seemanchal, this Ram Rajya began with a new, brazen hostility. We spoke to over a dozen children from the region—both Hindus and Muslims, all below the age of 14, and from low-income families of daily-wage labourers or small farmers—and observed this sentiment across the conversations. (We are choosing not to disclose their identities at the request of their parents and to protect the children from repercussions.) The hostility was most often reflected in aggressive remarks, targeted towards not just Muslim children, but even teachers. While the Ram Mandir led to a new, unabashed religious intolerance among children, surrounding factors played a crucial role, especially a parallel rise in polarising videos. The effect was a distinct feeling of alienation from even those whom they considered friends. “Santosh chacha’s son told me that when the doomsday comes, all Muslims will be driven away and all mosques will be replaced by temples,” the 11-year-old said, referring to a friend in his own neighbourhood. “Next, it’s the turn of the Taj Mahal.”

The significance of the Ram Mandir consecration in contemporary Indian politics cannot be understated. The attendees included RSS chief Mohan Bhagwat, and leading figures from the film and cricket industry including Amitabh Bachchan, Ranbir Kapoor, Alia Bhatt, Sachin Tendulkar, and Rajnikanth. “It seemed like the day of foundation for a Hindu Rashtra,” said Bhanwar Megwanshi, a Dalit activist and author who wrote a memoir, I Could Not Be Hindu, about quitting the RSS upon recognising the pervasive Brahminism within the Sangh. “It has to be acknowledged that in the last 100 years, RSS has never received as much recognition as it did on this day.”

For the children of Seemanchal, too, it was an important day, even if they did not understand the politics behind it. The Hindu children shared how the consecration ceremony was celebrated with joy and festivities at par with Diwali. For the Muslim children, on the other hand, the day was a sombre occasion at home. Two 12-year-old boys from the Araria town recalled how their families and other Muslim households in their neighbourhood observed a fast on the day. One of them noted that nobody on the live telecast of the consecration ceremony was Muslim. “It felt very alienating as we thought that no one stood with us,” one of them said. “My mother didn’t let me go out to play or use the phone that day.”

The other 12-year-old had gone to the market with his mother that day. He described seeing a group of boys walking around carrying saffron flags in their hands and playing loud Hindutva songs. “It seemed as if they had come to fight,” the 12-year-old said. “If there were some older Muslim boys there, then there would have been a fight.” He remembered the day vividly. “The whole street was filled with such flags. The police were standing right there but they didn’t do anything about the loud music. Later after some time, I saw that the police vehicle also had the same saffron flag on it.” (A police car with a Jai Shri Ram sticker was recently reported in Patna.)

In the Hindu children’s memory of the day, too, the alienation of Muslims featured prominently. An 11-year-old from Narpatganj town, in Araria district, said the inauguration ceremony was celebrated in his village with a feast. “While we were having food, I saw a few Muslims come to join us but they were asked to run away.” Another 11-year-old from Seemanchal’s Katihar city recalled how his village had organised a DJ to celebrate the ceremony, who played communal music despite ongoing tensions between his neighbourhood and a nearby Muslim neighbourhood. A 13-year-old from Araria town, who was otherwise shy and reserved, broke into song, “Awadh mein gao khoob badhai, ghadi mandir banne ki aayi”—Sing praises in Ayodhya as it is time to build the Ram temple. The 13-year-old added, “Muslims should be thrown out of the nation because they have their own country.”

All children appeared to unconsciously adopt such popular polarising narratives. One 12-year-old from Katihar expressed these anti-Muslim sentiments despite hailing from the Santhal tribe, and as such being outside the Hindu fold. His community worships the local deity Lankhi Mata during the harvest season and the goddess Kaali on Diwali. The 12-year-old had not even seen an idol of Ram in his village, and yet, joined his village in lighting diyas on 22 January to celebrate the consecration ceremony. “Muslims are considered bad people in our village because people say they eat cow meat,” he said.

In stark contrast to the boys, the girls we spoke to appeared to have very basic information about the Ram Temple, and did not reflect the same communal sentiments. Our conversations suggested two primary reasons for this: firstly, the gendered nature of household work resulted in the girls usually being occupied with chores at home after school, whereas the boys were freer to be social and unobserved. Secondly, and consequently, the girls had lesser access to mobile phones, while the boys were regularly using the phones of their family members, which seemed to be one of the strongest influences of the growing religious intolerance among children.

Education through YouTube Shorts

The brazen hostility among children witnessed in the weeks surrounding the Ram Mandir consecration was a new phenomenon. One explanation to emerge from the reporting was the internet consumption by the children, and the staggering popularity of hateful videos that the children began watching at a young age. The children had gained increasing access to use their family’s mobile phones during the pandemic, with the teaching conducted online, which simultaneously led to greater comfort with navigating the internet. That year, YouTube launched its Shorts section in India, which quickly became a favourite among the children. The primary form of entertainment for the children of the Seemanchal region were YouTube Shorts, Instagram reels and pop music videos, all of which presented distorted and over-simplified versions of history, each with an undercurrent of Hindu nationalist pride.

One 11-year-old from Narpatganj confessed to being hooked to YouTube Shorts of Hindu-Muslim clashes. He described one of his favourite videos with great excitement, repeating each line verbatim. “There is one video where one boy represents India and another boy in Muslim attire represents Pakistan, and the Hindu boy tells the Muslim boy, “Jitne tumhare yahan sainik hain, utne toh hamare yahan kaidi hain, shaam ko kaidi ki rehayi aur subah Pakistan ki safai.” (We have as many prisoners as you have army men. We will release our prisoners in the evening and by morning the entire Pakistan will be cleaned out.)

All the children we interviewed had watched such short videos with India-Pakistan representations, which invariably created an image in the children’s minds that anyone who wears a skull cap and a kurta-pyjama is a Muslim, and therefore, a Pakistani. Meanwhile, someone who wears a tilak and a saffron-coloured cloth around their neck becomes a “Hindustani.” The video described by the 11-year-old from Narpatganj had over 1.3 crore views.

Two YouTube channels that repeatedly came up in our conversations were Badal Debnath and Rahul indian boy, who had over 30 lakh and 8.5 lakh subscribers respectively, at the time of publishing. Even a cursory look at these channels reveals communal, misogynistic and hateful content. For instance, Rahul indian boy’s videos frequently showed Muslims as terrorists, often beating up an Indian army man. The videos were often violent, and included child actors dressed up as soldiers wearing skull caps, and acting out scenes of brutal murders of Indian soldiers with knives and rifles. The general tone and aim of the videos seemed to invoke patriotic fervour.

On the other hand, Badal Debnath channel compiles videos from different channels with a running theme of Hindu supremacy over Muslims, and generally pertain to Indian politics. Vishal Raj is a creator whose videos frequent the channel and are among its most popular. In most of Raj’s videos, the word “Pakistani” is often written above the Muslim character, played by a Hindu actor, and “Hindustani” above the Hindu characters. In one video, the Hindu character comes to the Muslim character and says, “There is good news for you and there is sad news. The good news is that the Ram temple has been built, the sad news is that now it is the turn of Kashi Mathura.” In another video, which has 4.5 crore views, a Muslim character says, “Brother, look, even the colour of mango is green.” The Hindu character responds, “It is green right now but it will have to turn saffron. If it doesn’t, then we Indians make chutney out of it.”

The Badal Debnath channel has uploaded over 380 videos since its launch in February 2023, all in the YouTube Shorts section, launched by the platform in September 2020. The channel’s early videos were edited clips of speeches by Modi and Dhirendra Krishna Shastri, a self-styled godman popularly known as Bageshwar Dham Sarkar. The Badal Debnath channel started posting Raj’s videos last June, which grew increasingly popular, and by August, one of the videos had received over 35 lakh views. In it, a boy in Muslim attire asks a Hindu boy, “What is the full form of BJP?” The Hindu boy replies, “The full form is Bharatiya Janata Party, but if you have a problem with BJP, then for people like you, it is Bhag Jao Pakistan.’” In the last eight months, the channel uploaded several videos by Raj targeting Muslims and asserting Hindu dominance.

On 30 September, the channel uploaded a video on the demolition of a mosque and the construction of a temple on the same site. The Hindu character then declares that even if the Muslim character produces documents to establish its title over the property, the records can be changed in parliament. The video received around 54 lakh views. It was among the channel’s most-viewed videos posted till then, and its subsequent Shorts focused more on the Hindu-Muslim divide and videos related to Hindu supremacy, which received high engagement.

Raj is an aspiring actor and dancer from Patna. Around one year ago, the 20-year-old teamed up with two friends, Aarav and Sahil, and started making sketch-comedy videos, some of which focused on Hindu supremacy, to post on their Instagram page, “badvish_.” He discovered that his communal videos were an instant hit. “Our first such video roasting Muslims was on the film The Kerala Story, which went viral and garnered 1 crore views,” Raj told us. “After that we realised how much people enjoy such videos so we kept making them.” He also mentioned that his Instagram page which had 96000 followers was removed by the platform but he made another page with the handle “_badvish_al,” and continues to post videos from it. Raj said that his family has tried to dissuade him from making videos targeting Muslims. “We don’t have any ill-intent towards the Muslim community, but our videos do well when we roast Muslims so we keep making these videos,” he added.

On the other hand, Raj was vocal about his support for the BJP and its authoritarian Hindutva politics. In reference to one of his videos about the Enforcement Directorate dropping cases against opposition politicians once they join the BJP, he said, “We enjoy the bulldozer politics and ED raids on opposition leaders.” Raj has even tried making a few videos on Hindu-Muslim unity but he said that his viewers widely criticised him for it. “They simply don’t work,” he said. “People start questioning our intent and troll us so we stick to roasting Abdul videos.”

Despite the highly political content of their videos, and even claiming to have received words of encouragement and promise of support from a local BJP leader on Instagram, Raj is uninterested in joining politics. He is currently in his second year of a Bachelor of Arts programme in a Patna college, but his dream is to break into the South Indian movie industry. He spends much of his time travelling through Uttar Pradesh and Bihar for small acting and dancing assignments. “I don’t want to be an Instagrammer or a Youtuber,” he said. “I’ll quit these platforms once I complete my studies and join the National School of Drama.”

Raj gave little thought to the impact of his videos on children. He acknowledged that the analytics of their Instagram channel had revealed that viewers in their early teens were their most popular demographic. Yet, he appeared surprised when informed that his videos were shaping the ideas of religion and communities for the young boys of Seemanchal. “I don’t know if I should feel happy or sad about this,” he said.

The Hindu children of Seemanchal all said the algorithm recommended Shorts from these channels, and that they enjoyed them because the videos were entertaining and instilled a sense of nationalistic pride. These videos were usually produced in a standardised format, with high-paced soundtracks and memes that disguised their hateful content as laughable entertainment. The format was efficient, given that the children all chuckled as they recalled the videos.

The Muslim children had seen the videos as well. The 12-year-old from Araria spoke about how the videos “make fun of my community and my God.” One video that stayed with him is one where the Hindu character complains to the Muslim character that a firecracker he bought does not burst, and asks him how he does it. The Muslim responds by demonstrating—he chants “Allahu Akbar”—God is great—and throws the firecracker, which immediately bursts. He then tells the Hindu character, “Do you see? The bomb blasts only after you say, ‘Allahu Akbar.’” The Hindu character asks him to repeat it, and then throws a cracker at him. At the time of publishing, this video had a staggering 3.8 crore views, 15 lakh likes and over 16,000 comments.

The most popular videos among the Muslim children also had heavy religious undertones, though they did not demonise the Hindu community. They primarily revolved around Islamic customs and the significance of being a good Muslim. In one video with over 2.4 crores views, by the channel “Insta team 0009,” which has 22.7 lakh subscribers, a milkman who swears falsely on Allah loses his tongue. “Mansoor official_22” is another popular channel with 97 lakh subscribers. In his second-most watched video, with over nine crore views, a Hindu boy returns a piggy bank lost by his Muslim neighbour, noting that money has no religion. Another video with over 89 lakh views compares two kinds of Muslims, one who goes to a public school and another who goes to a Madarsa, and ultimately shows how the latter is the better Muslim.

Bhojpuri Hindutva pop music also has a large viewership among boys in Bihar. These songs are repeatedly blared during rallies and processions by Hindu supremacist groups across the state. Songs such as “Har ghar bhagwa chhayega, Ram Rajya ab aayega” (Every house will be coloured in saffron and the rule of Ram will now come) and “Bharat ka baccha baccha Jai Shree Ram bolega (Every child of India will chant Jai Shree Ram) have replaced mainstream pop music in India’s hinterland. These songs, too, have gained in popularity amid the Ram Mandir celebrations, with new singers and musicians entering the fray. The songs often call upon Hindus to transform the nation into a Ram Rajya, and to wake up and point their swords at their enemies. The songs have viewership going into the millions.

Kunal Purohit, who recently wrote the book, H-Pop: The Secretive World of Hindutva Pop Stars, spoke to us about the youth audience of these musicians. “One of the insights my characters, the Popstars, would often lend me is that the young were a very crucial audience for them,” Purohit said. “In events that I attended with some of them, the young were integral and visibly active participants. However, I wouldn’t necessarily categorise them as children, but possibly in their teens/late teens and young adulthood. However, in Ram Navami rallies or in processions that were often brought out or supported by Hindu right-wing organisations, I spotted children playing an active role and, often, singing along to Hindutva pop songs that were being played by the DJ. This was something that was not restricted to rural, semi-rural areas but a phenomenon that I noticed in the heart of Mumbai.”

Purohit said that at its core, the popularity of H-Pop lay in its simplification of complex issues in a format that created easy, convenient narratives and opinions, for an audience that is not inclined to grapple with the nuances involved. “H-Pop captures them young and early and sets narratives about such characters and events so that they leave deep imprints on young minds,” he said.

Shifa Haq, an assistant professor of psychology-psychotherapy at the School of Human Studies at Ambedkar University, Delhi, spoke about the impact that such videos and interactions could have on children. “They negotiate feelings of love and attachment, sadness and insecurities,” Haq said. “If the outside environment is so hostile and overwhelming, not only do they not get help to cope with their complex feelings, they might repeat experiences of hate or be hated by scrolling through hate-filled short videos or messages that validate their feelings but do not offer any way out. This might keep them trapped, or give a fantasy of mastery in a provocative environment.”

AltEd is an activity-based initiative on media and information literacy curriculum for kids aged 12-14, which works with seven schools in and around Kolkata, and conducts focus-group discussions with the school children. A team member of AltEd, who requested to remain anonymous, shared insights on the trends of internet usage among children. They shared that during AltEd’s focus groups, the children unanimously admitted to using their phones throughout the day, and primarily during meals and tuitions. “Largely, we saw that the time children spend on phones is enormous and cuts across different income groups,” the team member said. “YouTube and WhatsApp are the two apps that children use the most. Between social media platforms, YouTube remains the most watched platform and they share the links from YouTube the most.”

The team member noted that the more surprising detail they discovered was that the way children verify the information shared in a particular short video was to go into the comment section. If a large number of people supported the video, they believe it to be true as well. “YouTube is designed infrastructurally to give you the content and also gives you a mechanism to verify it,” the team member said. “It’s deeply concerning to think that children believe that the mechanism to verify facts is built within the platform. They don’t have to look anywhere outside of that.”

By all metrics, YouTube consumption in India is significant. According to a 2024 report co-published by the Federation of Indian Chambers of Commerce and Industry and Ernst & Young, Indians alone constitute over 18 percent of YouTube users, with nearly 467 million monthly users. It is not only the largest online platform in India, it has even surpassed television in Bihar and Jharkhand. The FICCI-EY report further revealed that YouTube is the most preferred social-media platform for news consumption. At Google India’s Brandcast 2023 event in September last year, the tech giant revealed that YouTube Shorts’ average daily views grew by 120% year-on-year. Another report found that India spent 6.1 trillion minutes watching online videos between January 2022 and March 2023, 88 percent of which was on YouTube.

Purohit argued that platforms such as YouTube do little to combat the spread of misinformation, communal tensions and religious bias propagated in these videos, and instead serve to not just help these artists survive, but flourish. “These platforms have actively aided, by way of funding the creation of content that, sometimes, incites violence and stokes anger and fear against minorities and critics,” he said. “Thanks to the monetisation that platforms like YouTube as well as audio-streaming platforms offer, such creators get a continuous, and lucrative stream of income that allows them to continue making such hateful content.”

YouTube’s policies sound earnest on paper. It claims to fight misinformation, curb extremist content, and prevent bias, among other things. It also has a three-strike policy where the first strike can freeze an account for a week, the second strike freezes an account for two weeks and the third consecutive strike will result in the termination of a channel. “We’ve heavily invested in our policies and systems to successfully combat hate speech, and harmful and dangerous content on YouTube,” a spokesperson told us.

However, despite the videos containing misinformation about the country’s historical facts, hate-mongering and extremism are being peddled on the platform without justified consequences. Sandeep Acharya, a member of the Hindu extremist group Hindu Yuva Vahini, has openly spoken about how he circumvents YouTube’s policy. “According to their terms and conditions, it is hate speech,” he told the German public broadcaster Deutsche Welle. “A lot of my channels are suspended. But our reach is very high on the platform, so once a channel is taken down, I make another.” The YouTube spokesperson identified different channels and videos by Acharya that had been removed, including those posted by other channels such as Mayur Music and Janta Musical and Pictures. However, several videos of Acharya posted by the latter were still in wide circulation, including one titled, “Kisi Ke Bap Ki Nhi Ayodhya”—Ayodhya does not belong to anyone’s father—with 13 million views, containing clear divisive, anti-Muslim undertones, and posted in 2018.

In a written response, the YouTube spokesperson responded to queries with generic statements about their Community Guidelines policy, which sometimes raised further questions. The spokesperson listed out the policy against hate speech, dangerous or illegal activities, and violent or graphic content, as well as the thousands of channels and videos removed globally for violating these policies. According to Google’s Transparency Report for the last quarter of 2023, the platform removed over 2.25 million videos from India—the highest across the world. The spokesperson also noted that sometimes, “content that would otherwise violate our Community Guidelines may stay on YouTube when it has Educational, Documentary, Scientific, or Artistic (EDSA) context.”

The spokesperson said that YouTube had removed one video by the channel Rahul indian boy “for violating our harmful and dangerous policies.” It was not one of the violent videos flagged by us to them, and the channel remains active with numerous graphic videos of child actors depicting religious violence. The spokesperson did not respond to repeated follow-up queries about whether other videos by the Rahul indian boy channel and the Badal Debnath channel did not violate the guidelines, or if it had received an EDSA exception.

Religious discrimination in schools

The schools in Seemanchal, too, struggle to remain secular spaces. A school principal of one of Purnea’s biggest private schools, who requested to remain anonymous out of fear of backlash, shared that the socio-political climate of the country impacts the school environment as well. “We consciously ensure that we don’t let the communal tension enter academic spaces,” the principal said. Yet, even the school faculty were not spared the communal bullying.

“In one incident, a Muslim teacher was targeted by some students of class eighth who raised slogans of ‘Jai Shree Ram’ whenever he was around,” the principal recalled. “There have been some more incidents like this, so we try to talk to students and tell them that school is not a place for such slogans.” A history teacher in the school said she had been similarly targeted for her Muslim identity. “They acted like a mob loudly chanting ‘Jai Shree Ram,’ so I asked them whether this act of theirs will make Lord Ram happy,” the teacher said. “They responded saying that I’m only saying this because I’m a Muslim.”

However, while the principal expressed concerns about the growing religious intolerance among the students, the secular practices of the school are debatable. Within its premises, there is a temple for the Hindu goddess of knowledge, Saraswati. But the principal asserted that it was a secular institution that sought to celebrate all religious festivals harmoniously. “Our Muslim students have two periods off on Fridays for their prayers,” he said. “We celebrate Saraswati puja annually, and last year, we had a Muslim student lead the puja along with the priest.”

The principal noted that while he had not spoken to the Muslim student about the puja personally, “I am sure that our school would never force children into doing anything forcefully.” He added, “I wish we could celebrate Muslim festivals with the same rigour as we celebrate Hindu festivals but the political climate isn’t conducive to do so right now.”

The Purnea school is not alone in conducting Saraswati puja within the premises. Gauri Sharma, a principal of a government school in Araria, similarly told us that while they do not discriminate between children on religious identity, the school performs Saraswati puja every year.

According to the educationist Devyani Bhardwaj, for an efficient learning experience, Indian schools and curricula adopt context-based education, which allows children to bring the values of their home and community into the classroom. “However, if a teacher who is not properly trained, has certain social biases against a community’s customs, food habits and history, then these contexts are prone to be misinterpreted,” Bhardwaj added.

This was reflected in the teachings surrounding the Ram Mandir consecration within schools in Seemanchal. The 11-year-old from Narpatganj recalled the classroom discussions on 22 January: “Mere school mein ek teacher keh rahe the ki ab Hindu ka jaat badhta jayega aur Muslim ka jaat neecha girte jayega”—A teacher in my school said that now the status of Hindus will grow while that of the Muslims will decline.

The concept of the “hidden curriculum,” as coined by the American-Canadian scholar and cultural critic Henry Giroux also helps understand these practices in schools, and its impact on the students. According to Giroux, the hidden curriculum is the “unstated norms, values and beliefs transmitted to students through the underlying structures of schooling.” More simply put, as explained by Shaima Amatullah, a researcher at National Institute of Advanced Studies, it is the environment within the school beyond academics. This includes how a teacher talks to students, what kind of culture and rituals are followed in the school, how chapters around religious subjects are taught, all of which come together to form the experience of a student.

Amatullah believed that the hidden curriculum plays a crucial role in the actual curriculum—in fact, Giroux argued that students learn more from the former than the latter. “Oftentimes, the hidden curriculum is so normalised in schools’ overall atmosphere that subtle discriminations based on religion, gender, caste, class etc. don’t even come up for debate,” she said. “These routine practices mirror practices of the majoritarian group while excluding minorities and thus creating ‘the other’. To prove that the Muslim child has imbibed secular values, s/he needs to join the religious practices at the school while the Hindu child’s secular identity is never challenged.”

RK Yadav, a former social science teacher at a Kendriya Vidyalaya in Araria district, who retired in 2023 after two decades in service, emphasised that the teachers’ personal social and political ideology must not be delivered to the students. “Unfortunately, some teachers don’t adhere to this philosophy and let their personal views colour children’s minds as well,” Yadav added.

In this context too, the digital age has a major impact on the school experience. The history teacher from Purnea, noted the impact of the polarising media consumed by the students. “Previously there were discussions and debates in the classes, but now they speak whatever they listen on social media without verifying the factual basis of the information,” she said. “We are going through an acute educational crisis where the source of information for children is either YouTube or some WhatsApp forward. Recently, a student from my class told me he doesn’t like Gandhi because he begged from the Britishers. I’ve had students in my class who dissented against studying the Mughal Era, it’s bizarre.”

Not just the hidden curriculum, though, even the prescribed academic curriculum reinforces Hindutva narratives of history and society. Textbooks have long been a site of political contest in India, and the most recent edits point to a concerted effort to push the agenda of the Hindu nationalist ideology. In recent years, there have been significant revisions in the sections pertaining to the Mughal Era, the 2002 Gujarat pogrom and the caste system, with the most recent revisions concerning the section on the Ayodhya dispute in the NCERT’s Class XII political science textbook. The chapter spotlights the Ram Janmabhoomi movement and the Supreme Court verdict allowing the construction of the temple, while deleting at least three references to the demolition of the Babri Masjid that stood in its place.

It is important to also note how this religious radicalisation could impact various aspects of their lives growing up. Rachana Johari, a former professor at Ambedkar University whose research focused on psychology and gender, observed that due to the politics of religious polarisation, a sharp division of self and others starts forming in children, due to which they start developing stereotypes for various social categories. “They also learn that power and inequality is an integral part of the social structure,” Johri added. “If they have to control someone, then they should not control them with love, but by bullying or dehumanising them. They will do all this with the individuals or groups who do not form part of their self identity.”

On the other hand, the child psychologist Kalpana Purushottaman, who works with children in conflict with the law, noted that children from minority communities become so habituated to being attacked, threatened, or stereotyped, that their trauma response in any conversation is to be defensive. “On the other hand, children from dominant communities use their power and privilege to release their pent-up frustration on those coming from oppressed communities and are safe to hate,” she added. “As a society, we have created a scapegoat amongst Muslims.”

The constant bullying and harassment of children based on their Muslim identity can also lead to a responsive radicalisation. “This politics of hatred is also turning Muslim children against Hindus as well,” the social activist Shabnam Hashmi said. “Basically, children who develop this mindset don’t grow up to be humane human beings, but harbour violence and ultimately this violence will come out on everyone who they consider inferior to them including women.” Purushottaman reiterated this point, noting overt radicalisation reinforces misogyny and patriarchy in the society. “If the radicalisation is coming from children, it means that the younger generation is becoming even more conservative and patriarchal,” she added.

The old proverb “shared joy is double joy; shared sorrow is half a sorrow” loses meaning in the Ram Rajya, when the joy of the construction of a temple lies in the sorrow of the demolished mosque that stood in its place. While Hindu nationalism is much older than both the consecration of January 22 or even the Ram Janmabhoomi movement, the scale and vitriol of its penetration among children is a recent phenomenon. The children of Seemanchal have not been passive observers to this shift, but victims of religious hatred and alienation, taught by society to take joy in each other’s sorrows.

“I felt happy and excited by the happiness of the Hindus when they take out processions of Bol Bam or in celebration of the temple being built,” the 11-year-old from Araria town said. “But they say that now only Hindus can live in this area, it is hurtful.”

Editor’s Note: This article has been updated following an additional statement by YouTube, issued after the piece was published, about its actions concerning videos by Sandeep Acharya and the “Rahul indian boy” channel.

SUPPORT US

We like bringing the stories that don’t get told to you. For that, we need your support. However small, we would appreciate it.