The laws of sedition still occupy the dark statute books / Draconian laws run amok lawlessly / Free speech is as elusive as ever, social justice a mirage – A profile of GN Saibaba

“At no time have governments been moralists. They never imprisoned people and executed them for having done something. They imprisoned and executed them to keep them from doing something. They imprisoned all those prisoners of war, of course, not for treason to the motherland…They imprisoned all of them to keep them from telling their fellow villagers about Europe. What the eye doesn’t see, the heart doesn’t grieve for.”

― Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, The Gulag Archipelago, 1918-1956

‘Political Prisoner’ is a category of criminal offense that sits most egregiously in any civilized society, especially in countries that call themselves liberal democracies. It is a thought crime: the crime of thinking, acting, speaking, probing, reporting, questioning, demanding rights, and, more importantly, exercising one’s citizenship. But these inhumane incarcerations do not just target private acts of courage, they are bound together with the fundamental questions of citizenship, and with people’s capacity to hold the State accountable. Especially States that are unilaterally and fundamentally remaking their relationship with their people. The assault on the fundamental rights has been consistent and ongoing at a global level and rights-bearing citizens are transformed into consuming subjects of a surveillance State.

In this transforming landscape, dissent is sedition, and resistance is treason.

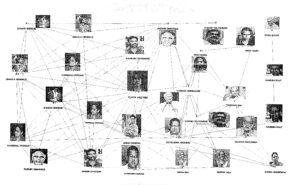

While the Indian State has a long history of ruthlessly crushing dissent, a new wave of arrests began in 2018. Eleven prominent writers, poets, activists, and human rights defenders have been in prison, held under the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act. They are accused of being members of a banned Maoist organization, plotting to kill Prime Minister Narendra Modi, and inciting violent protests in Bhima Koregaon. To date, no credible evidence has been produced by the investigating agency, and those accused remain incarcerated without bail. Since the anti-Citizenship Amendment Act protest began in December 2019, students, activists, and peaceful protesters have been charged with sedition, targeted with violence, and subjected to arrests. Since then, more arrests have followed specifically targeting local Muslim students leader and protestors, including twenty-seven-year-old student leader Safoora Zargar, who is currently pregnant.

Since the COVID-19 lockdown was announced, India’s leading public intellectuals, opposition leaders, writers, thinkers, activists, and scholars have written various appeals to the Narendra Modi government for the release of India’s political prisoners. They are vulnerable to COVID-19 contagion in the country’s overcrowded jails, where three coronavirus-related deaths have already been reported. In response, the State has doubled down and rejected all the bail applications. It also shifted the seventy-year-old journalist Gautham Navlakha from Delhi’s Tihar Jail to Taloja, without any notice or due process – Taloja is one of the prisons where a convict has already died of COVID-19.

A fearful, weak State silences the voice of dissent. Once it has established repression as a response to critique, it has only one way to go: become a regime of authoritarian terror, where it is the source of dread and fear to its citizens.

How do we live, survive, and respond to this moment?

In collaboration with maraa, The Polis Project is launching Profiles of Dissent. This new series centers on remarkable voices of dissent and courage, and their personal and political histories, as a way to reclaim our public spaces.

Profiles of Dissent is a way to question and critique the State that has used legal means to crush dissent illegally. It also intends to ground the idea that, despite the repression, voices of resistance continue to emerge every day.

The following excerpt is published from maraa, READ ALOUD: Ideas Can Never Be Arrested. You can read Varavara Rao’s profile here and the profile of Sudha Bharadwaj here.

G.N. SAIBABA

Growing up the polio-stricken son of a rural South Indian farmer, G.N. Saibaba experienced prejudice firsthand and decided to devote his life to fighting for the rights of the most marginalized groups in India. Born in Andhra’s Amalapuram in 1967, Saibaba hailed from a poor family. Unable to afford more than basic schooling, his academic rigor ensured scholarships throughout—so much so that he finished at the top of his university. Later, as an activist of the All India People’s Resistance Forum (AIPRF), he traveled over two hundred thousand kilometers to speak in support of liberation movements in Kashmir and the Northeast, and campaign for Dalit and Adivasi rights.

He taught at Sri Venkateswara College for three months in 2003, before moving to Ram Lal Anand College in Delhi University. Saibaba has also been a vocal critic of “Operation Greenhunt”, a clean-up operation by paramilitary forces against Maoists in the jungles of central India.

Saibaba’s activism was deeply ingrained in his practice of teaching. His Ph.D. was on the elite bias toward English writing in Indian Literature. Students recollect that he would come for classes even when there was only one student enrolled. He was never late and, in spite of his physical condition, rarely missed a day of teaching.

Date of Arrest: 9 May 2014

Charges: In May 2014, as Saibaba was being driven home from college, a van abruptly stopped his vehicle and a man dressed as a civilian yanked the driver from the seat whilst two others took Saibaba into the van and drove off. When he didn’t return for lunch, his wife tried to contact the driver but without any success. She later received a call from an unknown man who told her Saibaba was in the custody of the Maharashtra state police. His arrest had been preceded by a raid in 2013, during which his books, laptops, and hard disks were seized. Saibaba was charged under the UAPA with Sections 13 (taking part in advocating / abetting / inciting the commission of unlawful activity), Section 18 (conspiring/attempting to commit a terrorist act), Section 20 (being a member of a terrorist gang or organization), Section 38 (associating with a terrorist organization with intention to further its activities), and Section 39 (inviting support and addressing meetings for the purpose of (encouraging support for a terrorist organization).

He remains imprisoned to date and has been denied adequate health care which has led to a deterioration of his physical, emotional, and mental state. Saibaba was handed a life sentence on 7 March 2018. He suffers from a number of life-threatening ailments and has lost most of the functioning of both his hands since being imprisoned.

Update: Having had polio since he was five, Saibaba is wheelchair-bound and his body is ninety percent paralyzed. He remains imprisoned to date and has been denied adequate health care which has led to a deterioration of his physical, emotional, and mental state. Saibaba was handed a life sentence on 7 March 2018. He suffers from a number of life-threatening ailments and has lost most of the functioning of both his hands since being imprisoned.

Location of Work: New Delhi

Update 15 June 2020: On 22 May 2020, the Bombay High Court preceded by justice RK Deshpande and justice Amit Borkar rejected a plea for parole leave filed by professor GN Saibaba on the grounds that, given his deteriorating medical condition, the COVID-19 pandemic would put him at further risk and that he would need to assist his mother, who is suffering from cancer.

In June 2020, in response to the rejection of his parole, about 100 renowned intellectuals from across the world appealed to the Indian President Ram Nath Kovind and the Chief Justice of India S.A. Bobde to release Professor GN Saibaba and activist Varavara Rao, saying they have been imprisoned in “fabricated cases” and that they are vulnerable to infection in the “overcrowded Maharashtra prisons.” Among the signatories are Noam Chomsky, Judith Butler, Partha Chatterjee, Homi K. Bhabha, Bruno Latour, Gerald Horne, and Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o. They said that Saibaba, who is 90% disabled with post-polio syndrome, does not have proper access to medical care: “The continued negligence of jail authorities is effectively a death sentence for him during the COVID-19 pandemic.”

***

The Persecution of GN Saibaba and India’s annihilation of the resistance – excerpted from an article by Tekendra Parmar

In the summer of 2017, in a small redbrick duplex off of south Delhi’s Nelson Mandela Road, I met AS Vasantha, Saibaba’s partner of fifteen years. Vasantha told me of how their ordeal began on a mid-September afternoon in 2013. Saibaba had just returned home after a day of lecturing when a joint task force of the local police and the country’s anti-terrorism unit raided their home.

The police took him to Nagpur Central Prison in Maharashtra, where he would spend nearly two years as an under-trial, a kind of legal purgatory in which the accused remains imprisoned until the resolution of the case. Saibaba was held in the notorious and a cell reserved for the most notorious of criminals and terrorists. He was also denied adequate medical care. More than forty officers surrounded the building while seven rushed into the house, seizing the professor’s cell phone and blocking the entrances. “They were looking for all our books with red bindings,” Vasantha said, referring to the left-wing magazines and pamphlets strewn across the couple’s dining and coffee tables. Under Indian criminal law, searches and seizures must happen in the presence of a civilian witness. Knowing this, the professor asked the investigating officer to allow his university colleagues or his lawyer to witness the search. The officers denied him on both counts. Instead, according to Vasantha, two illiterate barbers were stationed outside the residence and made to sign off on a seizure list they could not read. The police confiscated laptops, hard drives, pen drives containing the professor’s Ph.D. work, three books he was writing, family photos, and even Saibaba and Vasantha’s fifteen-year-old daughter’s homework assignments. Speaking to the press after the raid, Saibaba was nonchalant. He told a local paper, “I’ve said I’m willing to cooperate and asked them to let me know the timing, so my teaching is not disrupted.”

The police took him to Nagpur Central Prison in Maharashtra, where he would spend nearly two years as an under-trial, a kind of legal purgatory in which the accused remains imprisoned until the resolution of the case. Saibaba was held in the notorious and a cell reserved for the most notorious of criminals and terrorists. He was also denied adequate medical care.

At the trial, Saibaba said, “Even the senior police officers who attended the trial … couldn’t control themselves but to laugh at the kind of evidence that came up before the court.” He was released on bail in 2016. However, his release was short-lived. The final verdict found Saibaba guilty on all counts, “including” murders, abductions, and arson. Most controversially, the prosecution claimed the Revolutionary Democratic Front (RDF), an organization dedicated to various progressive causes, in which Saibaba held the position of joint secretary, was actually a Maoist front. While admitting it shares similar concerns for Adivasi rights, the RDF has denied any association with the banned Maoist Party.

For his part, Saibaba has also condemned Naxal violence, having written a piece in 2010, titled “Revolutionaries Do Not Kill Policemen,” that denounced the murder of a police officer by Maoists. At the trial, Saibaba said, “Even the senior police officers who attended the trial … couldn’t control themselves but to laugh at the kind of evidence that came up before the court.”

In prison, Saibaba’s health was deteriorating rapidly… The professor tried to assure his family that he was fine, shifting the conversation to their daughter’s schooling and to a translation of Ngugi wa Thiong’o’s “Dreams in a Time of War” into the Telugu that he was secretly working on. In prison, Saibaba’s health was deteriorating rapidly… The professor tried to assure his family that he was fine, shifting the conversation to their daughter’s schooling and to a translation of Ngugi wa Thiong’o’s “Dreams in a Time of War” into the Telugu that he was secretly working on. In his anda cell, Saibaba would write on reams of paper hidden from the prison guards—much like the Kenyan author himself, who secretly wrote on toilet-paper while incarcerated for his outspoken political beliefs.

In April 2016, after he was granted bail, Saibaba returned to visit his students and appeal for his reinstatement but he faced the sorts of slurs that are now a familiar part of Indian public life. Akhil Bharatiya Vidyarthi Parishad (ABVP) members shouted insults, labeling Saibaba a “desh-drohi,” or traitor, as others tried to physically attack him. Students who supported him formed a human chain around the disabled professor to protect him, but during the scuffle, he was burned by a cup of scalding tea. Administrators chastised Saibaba for returning to campus, and the professor’s appeal for reinstatement was denied. Through Surendra Gadling, his lawyer at the time, and the professor’s family, I started writing letters to Saibaba.

In our first exchange, Saibaba confirmed rumors that he wasn’t receiving the medicine necessary for his survival: “When I wrote a complaint letter to jail higher officials…I have gotten threats on my life.” He told me that he longs to go back to academia: “Because of my disability it took a lot of time for me to establish a base for my studies,” Saibaba wrote, referring to the early discrimination he felt as a wheelchair-bound academic. Before his conviction, the professor was mentoring seven Ph.D. candidates and writing a book about 200 years of Indian literature written in English.

Now, he wrote to me, “All my dreams and plans have been scuttled. Many a time I feel despaired sitting alone in my solitary cell. The more I think about all this, the more I get despaired. On the weather inside his cell: “I must say it’s a great architecture, when you need the sun there is no sun at all. When you try to protect yourself from the sun, the sun is all over you.”Now, he wrote to me, “All my dreams and plans have been scuttled. Many a time I feel despaired sitting alone in my solitary cell. The more I think about all this, the more I get despaired. On the weather inside his cell: “I must say it’s a great architecture, when you need the sun there is no sun at all. When you try to protect yourself from the sun, the sun is all over you.” These days Saibaba still writes poetry about his desire to reunite with his family and to return to the classroom. But when the time came to answer my questions, despite releasing statements on controversial issues from prison in the past, the professor told me he now had to choose his words carefully:

“If I want my letter to reach you, I better censor my own words.”

“Waiting is a game, a cruel game. Pain and suffering consume [me],” he writes toward the end of our last exchange.

“I once again thank you for your letter. Unfortunately, I can’t write more than this.

My hands heart and mind are under fetters.

Related Posts

The laws of sedition still occupy the dark statute books / Draconian laws run amok lawlessly / Free speech is as elusive as ever, social justice a mirage – A profile of GN Saibaba

G.N. SAIBABA

Growing up the polio-stricken son of a rural South Indian farmer, G.N. Saibaba experienced prejudice firsthand and decided to devote his life to fighting for the rights of the most marginalized groups in India. Born in Andhra’s Amalapuram in 1967, Saibaba hailed from a poor family. Unable to afford more than basic schooling, his academic rigor ensured scholarships throughout—so much so that he finished at the top of his university. Later, as an activist of the All India People’s Resistance Forum (AIPRF), he traveled over two hundred thousand kilometers to speak in support of liberation movements in Kashmir and the Northeast, and campaign for Dalit and Adivasi rights.

He taught at Sri Venkateswara College for three months in 2003, before moving to Ram Lal Anand College in Delhi University. Saibaba has also been a vocal critic of “Operation Greenhunt”, a clean-up operation by paramilitary forces against Maoists in the jungles of central India.

Saibaba’s activism was deeply ingrained in his practice of teaching. His Ph.D. was on the elite bias toward English writing in Indian Literature. Students recollect that he would come for classes even when there was only one student enrolled. He was never late and, in spite of his physical condition, rarely missed a day of teaching.

Date of Arrest: 9 May 2014

Charges: In May 2014, as Saibaba was being driven home from college, a van abruptly stopped his vehicle and a man dressed as a civilian yanked the driver from the seat whilst two others took Saibaba into the van and drove off. When he didn’t return for lunch, his wife tried to contact the driver but without any success. She later received a call from an unknown man who told her Saibaba was in the custody of the Maharashtra state police. His arrest had been preceded by a raid in 2013, during which his books, laptops, and hard disks were seized. Saibaba was charged under the UAPA with Sections 13 (taking part in advocating / abetting / inciting the commission of unlawful activity), Section 18 (conspiring/attempting to commit a terrorist act), Section 20 (being a member of a terrorist gang or organization), Section 38 (associating with a terrorist organization with intention to further its activities), and Section 39 (inviting support and addressing meetings for the purpose of (encouraging support for a terrorist organization).

He remains imprisoned to date and has been denied adequate health care which has led to a deterioration of his physical, emotional, and mental state. Saibaba was handed a life sentence on 7 March 2018. He suffers from a number of life-threatening ailments and has lost most of the functioning of both his hands since being imprisoned.

Update: Having had polio since he was five, Saibaba is wheelchair-bound and his body is ninety percent paralyzed. He remains imprisoned to date and has been denied adequate health care which has led to a deterioration of his physical, emotional, and mental state. Saibaba was handed a life sentence on 7 March 2018. He suffers from a number of life-threatening ailments and has lost most of the functioning of both his hands since being imprisoned.

Location of Work: New Delhi

Update 15 June 2020: On 22 May 2020, the Bombay High Court preceded by justice RK Deshpande and justice Amit Borkar rejected a plea for parole leave filed by professor GN Saibaba on the grounds that, given his deteriorating medical condition, the COVID-19 pandemic would put him at further risk and that he would need to assist his mother, who is suffering from cancer.

In June 2020, in response to the rejection of his parole, about 100 renowned intellectuals from across the world appealed to the Indian President Ram Nath Kovind and the Chief Justice of India S.A. Bobde to release Professor GN Saibaba and activist Varavara Rao, saying they have been imprisoned in “fabricated cases” and that they are vulnerable to infection in the “overcrowded Maharashtra prisons.” Among the signatories are Noam Chomsky, Judith Butler, Partha Chatterjee, Homi K. Bhabha, Bruno Latour, Gerald Horne, and Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o. They said that Saibaba, who is 90% disabled with post-polio syndrome, does not have proper access to medical care: “The continued negligence of jail authorities is effectively a death sentence for him during the COVID-19 pandemic.”

***

The Persecution of GN Saibaba and India’s annihilation of the resistance – excerpted from an article by Tekendra Parmar

In the summer of 2017, in a small redbrick duplex off of south Delhi’s Nelson Mandela Road, I met AS Vasantha, Saibaba’s partner of fifteen years. Vasantha told me of how their ordeal began on a mid-September afternoon in 2013. Saibaba had just returned home after a day of lecturing when a joint task force of the local police and the country’s anti-terrorism unit raided their home.

The police took him to Nagpur Central Prison in Maharashtra, where he would spend nearly two years as an under-trial, a kind of legal purgatory in which the accused remains imprisoned until the resolution of the case. Saibaba was held in the notorious and a cell reserved for the most notorious of criminals and terrorists. He was also denied adequate medical care. More than forty officers surrounded the building while seven rushed into the house, seizing the professor’s cell phone and blocking the entrances. “They were looking for all our books with red bindings,” Vasantha said, referring to the left-wing magazines and pamphlets strewn across the couple’s dining and coffee tables. Under Indian criminal law, searches and seizures must happen in the presence of a civilian witness. Knowing this, the professor asked the investigating officer to allow his university colleagues or his lawyer to witness the search. The officers denied him on both counts. Instead, according to Vasantha, two illiterate barbers were stationed outside the residence and made to sign off on a seizure list they could not read. The police confiscated laptops, hard drives, pen drives containing the professor’s Ph.D. work, three books he was writing, family photos, and even Saibaba and Vasantha’s fifteen-year-old daughter’s homework assignments. Speaking to the press after the raid, Saibaba was nonchalant. He told a local paper, “I’ve said I’m willing to cooperate and asked them to let me know the timing, so my teaching is not disrupted.”

The police took him to Nagpur Central Prison in Maharashtra, where he would spend nearly two years as an under-trial, a kind of legal purgatory in which the accused remains imprisoned until the resolution of the case. Saibaba was held in the notorious and a cell reserved for the most notorious of criminals and terrorists. He was also denied adequate medical care.

At the trial, Saibaba said, “Even the senior police officers who attended the trial … couldn’t control themselves but to laugh at the kind of evidence that came up before the court.” He was released on bail in 2016. However, his release was short-lived. The final verdict found Saibaba guilty on all counts, “including” murders, abductions, and arson. Most controversially, the prosecution claimed the Revolutionary Democratic Front (RDF), an organization dedicated to various progressive causes, in which Saibaba held the position of joint secretary, was actually a Maoist front. While admitting it shares similar concerns for Adivasi rights, the RDF has denied any association with the banned Maoist Party.

For his part, Saibaba has also condemned Naxal violence, having written a piece in 2010, titled “Revolutionaries Do Not Kill Policemen,” that denounced the murder of a police officer by Maoists. At the trial, Saibaba said, “Even the senior police officers who attended the trial … couldn’t control themselves but to laugh at the kind of evidence that came up before the court.”

In prison, Saibaba’s health was deteriorating rapidly… The professor tried to assure his family that he was fine, shifting the conversation to their daughter’s schooling and to a translation of Ngugi wa Thiong’o’s “Dreams in a Time of War” into the Telugu that he was secretly working on. In prison, Saibaba’s health was deteriorating rapidly… The professor tried to assure his family that he was fine, shifting the conversation to their daughter’s schooling and to a translation of Ngugi wa Thiong’o’s “Dreams in a Time of War” into the Telugu that he was secretly working on. In his anda cell, Saibaba would write on reams of paper hidden from the prison guards—much like the Kenyan author himself, who secretly wrote on toilet-paper while incarcerated for his outspoken political beliefs.

In April 2016, after he was granted bail, Saibaba returned to visit his students and appeal for his reinstatement but he faced the sorts of slurs that are now a familiar part of Indian public life. Akhil Bharatiya Vidyarthi Parishad (ABVP) members shouted insults, labeling Saibaba a “desh-drohi,” or traitor, as others tried to physically attack him. Students who supported him formed a human chain around the disabled professor to protect him, but during the scuffle, he was burned by a cup of scalding tea. Administrators chastised Saibaba for returning to campus, and the professor’s appeal for reinstatement was denied. Through Surendra Gadling, his lawyer at the time, and the professor’s family, I started writing letters to Saibaba.

In our first exchange, Saibaba confirmed rumors that he wasn’t receiving the medicine necessary for his survival: “When I wrote a complaint letter to jail higher officials…I have gotten threats on my life.” He told me that he longs to go back to academia: “Because of my disability it took a lot of time for me to establish a base for my studies,” Saibaba wrote, referring to the early discrimination he felt as a wheelchair-bound academic. Before his conviction, the professor was mentoring seven Ph.D. candidates and writing a book about 200 years of Indian literature written in English.

Now, he wrote to me, “All my dreams and plans have been scuttled. Many a time I feel despaired sitting alone in my solitary cell. The more I think about all this, the more I get despaired. On the weather inside his cell: “I must say it’s a great architecture, when you need the sun there is no sun at all. When you try to protect yourself from the sun, the sun is all over you.”Now, he wrote to me, “All my dreams and plans have been scuttled. Many a time I feel despaired sitting alone in my solitary cell. The more I think about all this, the more I get despaired. On the weather inside his cell: “I must say it’s a great architecture, when you need the sun there is no sun at all. When you try to protect yourself from the sun, the sun is all over you.” These days Saibaba still writes poetry about his desire to reunite with his family and to return to the classroom. But when the time came to answer my questions, despite releasing statements on controversial issues from prison in the past, the professor told me he now had to choose his words carefully:

“If I want my letter to reach you, I better censor my own words.”

“Waiting is a game, a cruel game. Pain and suffering consume [me],” he writes toward the end of our last exchange.

“I once again thank you for your letter. Unfortunately, I can’t write more than this.

My hands heart and mind are under fetters.

SUPPORT US

We like bringing the stories that don’t get told to you. For that, we need your support. However small, we would appreciate it.