Four Decades Later, No City for Women Echoes the Enduring Impact of Yugantar Film Collective’s Path-Breaking Documentaries

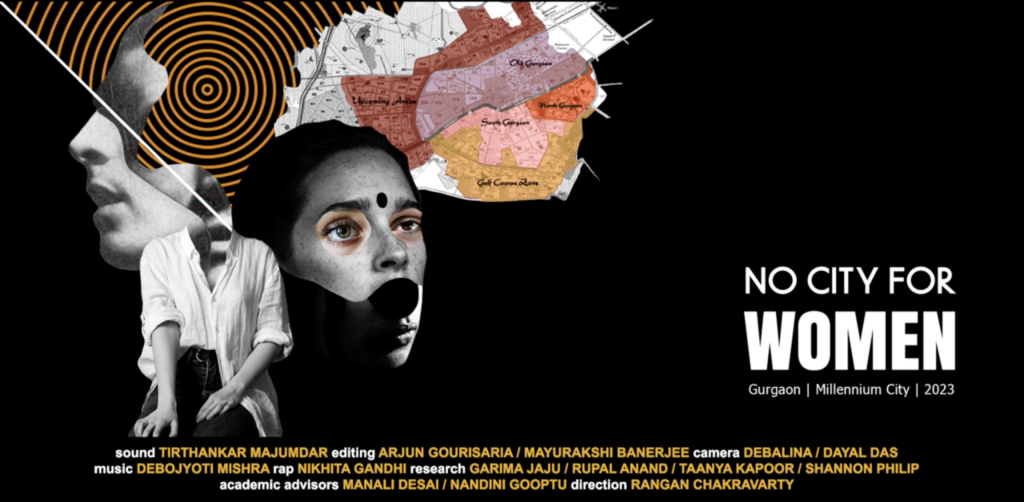

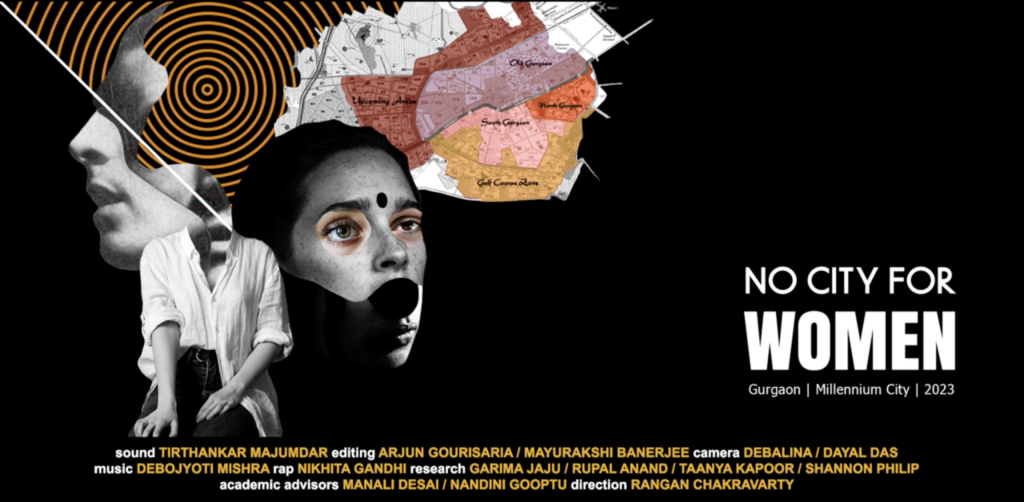

At the end of Dr. Rangan Chakravarty’s documentary film No City for Women—a piercing look at modern day Gurgaon, its beginnings, and its growth into an unsafe concrete jungle—we see three women around a table. In the middle is the upper-class homeowner and employer living in one of the city’s ubiquitous gated communities. Two domestic workers, both women, are at her side. The interviewer behind the camera asks, “Is there a new mindset in Gurgaon?”

The woman on the right nods and explains how there is an expectation and demand for domestic workers who dress well (“pant-shirt wale”) and are smart and light-skinned. Their employer has a horrified look on her face. “To work?!” she exclaims. The woman on the right tells her, only half-jokingly, that one of her employer’s friends is among them. “Are you serious?” the employer responds. “Whisper her name to me!” The woman bursts into laughter but does not divulge.

No City for Women premiered in 2023 at Beyond Borders Feminist Film Festival held in New Delhi. The film is not about domestic workers—it looks, instead, at the larger plight of women navigating the unsafe city of Gurgaon. But the concerns of the domestic workers and working-class women in the film harks back to Molkarin (Maid Servant), one of several short documentaries made by Yugantar Film Collective in 1981.

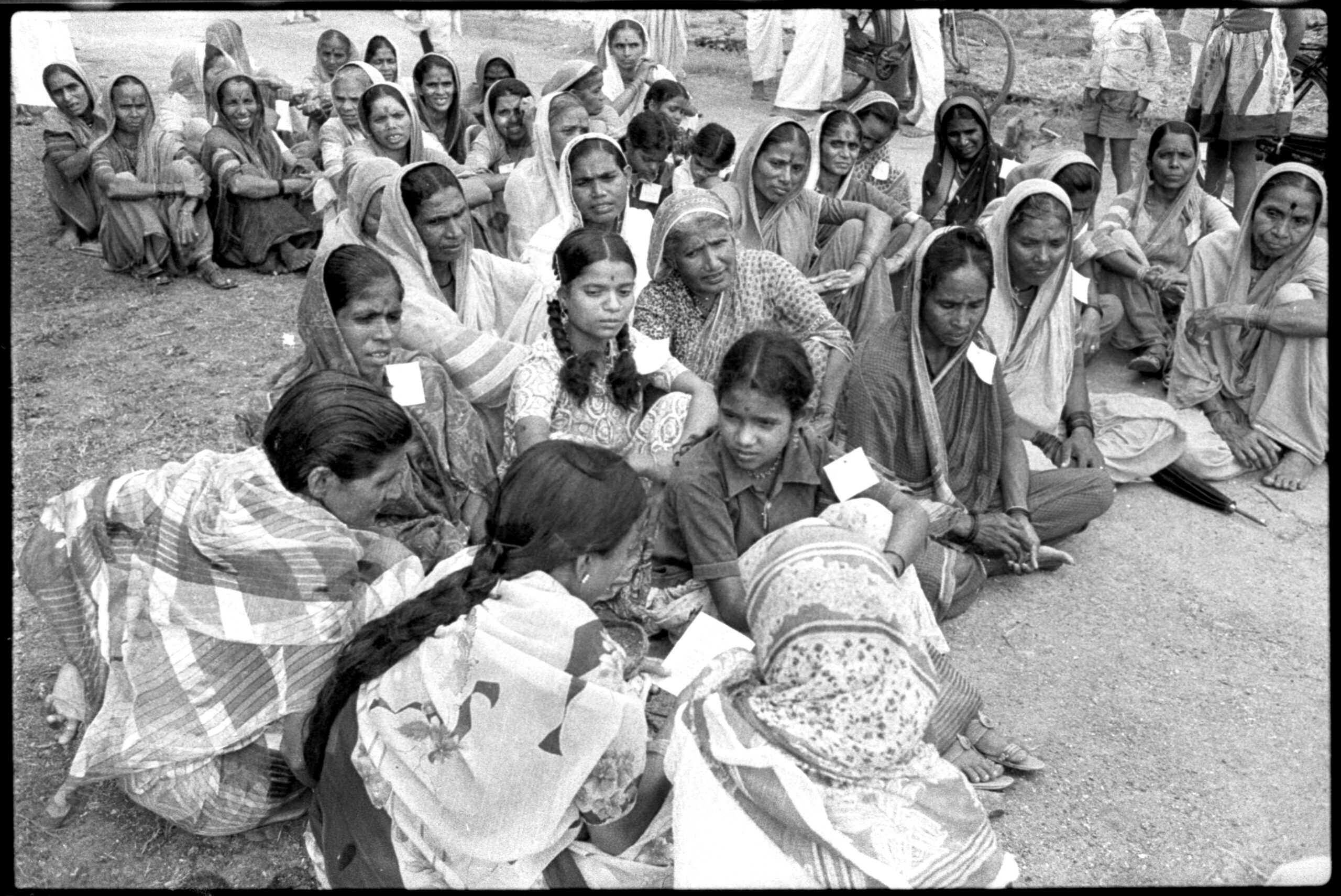

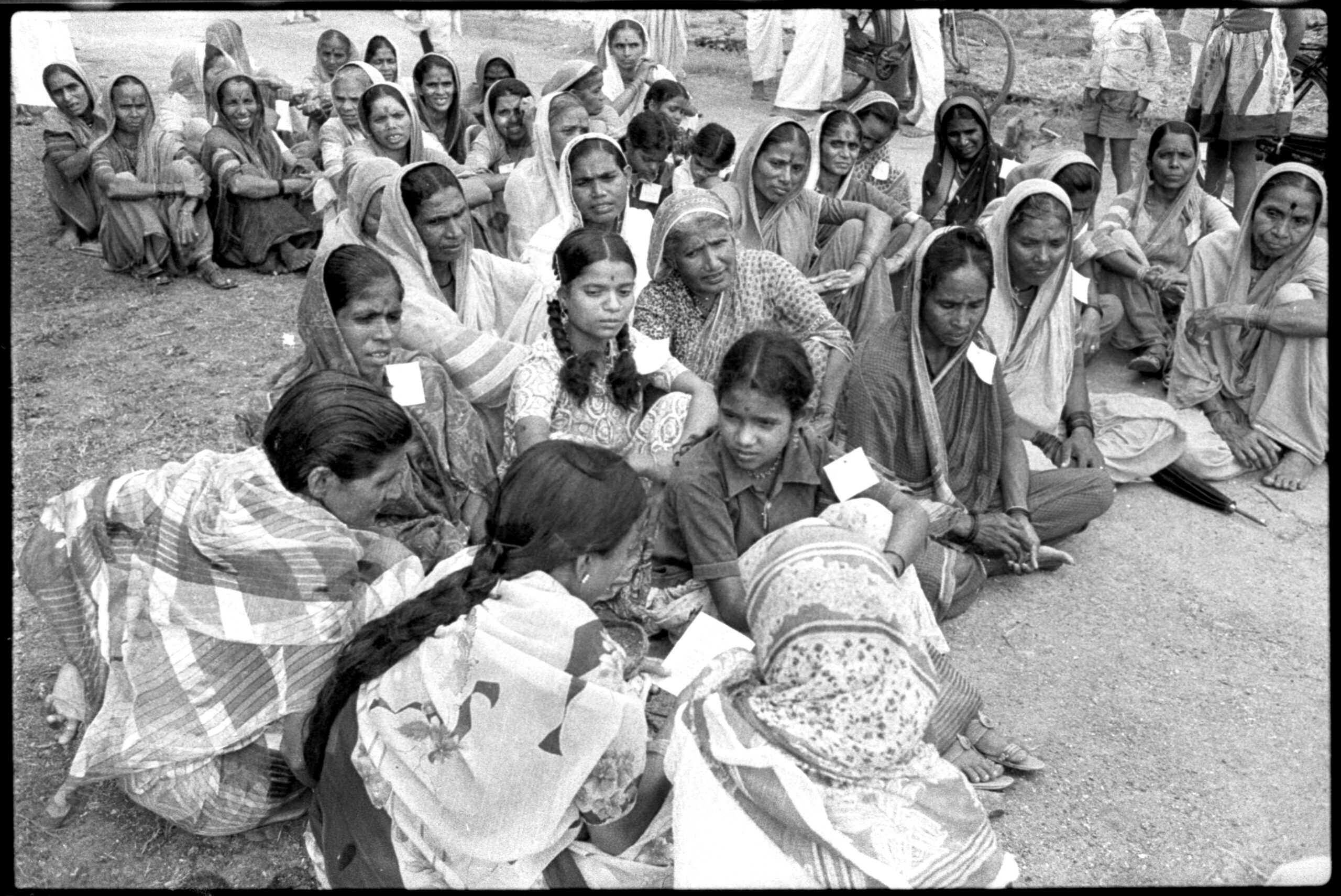

Molkarin documents the protests and unionizing efforts of domestic workers in Pune, and their demand for rights and better working conditions. The film exposes not just the low wages of these workers, but also hostile treatment by employers, lack of holidays, and everyday casteism in the workplace.

About four decades separate Molkarin and No City for Women. In the intervening period, India has gone through several churns: from the rise of Hindutva, economic liberalization, and an endless wave of free market capitalism, to the present state of dictatorial democracy dominated by BJP’s Hindu right-wing government that actively works towards disenfranchising minorities.

India’s first feminist film collective, Yugantar was founded in 1980 by filmmakers and activists Deepa Dhanraj, Abha Bhaiya, Navroze Contractor, and Meera Rao in Bangalore. It was the first documentarian effort that highlighted feminist discourse, underlining caste and intersectionality that permeates social, political, and economic transactions in India.

The period of Yugantar’s foundation was an inchoate one of ideological shifts, since the country was coming to terms with the failure of the Nehruvian development model. It was marked by Indira Gandhi’s Emergency (1975-1977), which occurred with the nascent Naxalite movement, protests in Gujarat amidst an economic crisis, suppressed student movements in Bihar, and the quelled strike of the railway employees’ union. Movements like Nav Nirman saw women enter the protests in a big way, backed by the organizations they had formed. The post-Emergency period was colored by weary socialist leaders with neither drive nor popular support, and the opportunists who renewed their dreams for an India redrawn as a Hindu society.

It is a film movement that mirrored the reality of women entering public life in different roles and across demographics. Several women-led organizations came into their own for collective action during this period. For example, the Self-Employed Women’s Association was established as a trade union in Ahmedabad in 1972. Other women’s groups—like Progressive Organization of Women in Hyderabad, Stree Sangharsh, and Mahila Dakshata Samiti—came together for anti-dowry movements in the late 1970s.

Rooted in this time, the collective made four short documentaries between 1980 and 1983, filmed on 16mm, that captured an Indian society seldom given the privilege of image-making. Apart from Maid Servant, there are Tobacco Embers/Tambaku Chaakila Oob Ali (1982), Is This Just a Story/Idhi Katha Matramena (1983) and Sudesha (1983).

The documentaries blend fiction and non-fiction, with some rallying moments staged for recreation. In Maid Servant, Pune’s domestic workers form a union, Pune Shahar Molkarin Sanghatana (Pune City Domestic Workers Union), and express their righteous indignation at how poorly they are paid and treated. Their demands are not only just, but also sprawling: increase in wages, two holidays without pay cut, no pay cut if they go on leave, one month bonus, holidays for festivals, and no caste discrimination.

The last demand covers a gamut of societal issues—a domestic worker talks about how there are separate plates and glasses for them where they work. Blatant casteism is pervasive within the Indian middle and upper classes, and manifests in more nefarious ways today. Maid Servant also shows three generations of domestic workers in a family, all women, questioning why and how housework is traditionally considered women’s work and therefore undervalued.

In Sudesha, in the foothills of Himalayas far away from Maid Servant’s Pune, we meet Sudesha Devi who is an activist in the Chipko Movement fighting against deforestation and timber traders. Forestry remains their livelihood, and women carry the burden of the family. The film tracks Sudesha and other women working the fields, collecting bushes, crushing grains, cooking and cleaning at home, and routinely and sarcastically wondering if the men of the household will return for dinner. They are also active participants of the Chipko Movement, putting their bodies between the axe and the tree, for which they have been jailed. Sudesha mentions how, with the shrinking number of trees, every year they need to walk farther into the forest for firewood.

These films are not without the moments of levity. Like the woman pretending to be her drunk husband in Maid Servant, even Sudesha packs in tongue-in-cheek moments. The women declare that men can do nothing but plow—something the women can do themselves—and how their two weeks in jail was truly the best of times, as there was warm food, no work, and plenty of sleep.

More recently, No City for Women focuses heavily on Gurgaon’s gated communities: the upscale apartment complexes that are self-contained universes, with amenities for shopping as well as leisure. A resident jokes that a school inside is all that is needed. These gated communities are now present in every major city in India. Their proliferation has created two divergent worlds, one that is inside—insular, seemingly “safe” and disconnected—and the one that is outside, considered polluted and populated by the nebulous “other”, namely the working class, who the “insiders” view with disdain, disguised as fear.

Even within the “inside” world, these communities have separate elevators for gig and domestic workers, and mobile apps that control and surveil everyone’s entry and exit. The “inside” and the “outside” never mingle; this separation is desired. It creates a deeper class and caste divide that is more pronounced than the one we see in Maid Servant and Sudesha.

The Yugantar films from the early 1980s echo louder today, as the demands made by the domestic workers or the daily troubles of Sudesha sound almost quaint in 2024. Indian casteism has now made its way to diasporic communities abroad. Earlier this year, a Swiss court sentenced four members of the Hinduja family—one of the wealthiest families in the United Kingdom—to four years and six months in jail for trafficking and exploitation of their Indian domestic workers. State sponsored and endorsed targeting of minorities, coupled with violent suppression of dissenting voices, has emboldened the middle and upper classes in India to maintain their positions of power.

Yugantar began as an effort to separate documentary filmmaking from state funding, bringing it into the independent realm. This resulted in four important films that inspected fundamental fractures in Indian society, in which the subject-protagonists in front of the camera and the filmmaker-activists behind it were equal participants in a solidarity-building exercise.

Some of the sharpest political filmmaking in India today comes from documentaries. Yet, they lack reliable funding options and distribution networks, despite covering some of the most necessary stories. Films like Rintu Thomas and Sushmit Ghosh’s Writing with Fire, Payal Kapadia’s A Night of Knowing Nothing, Shaunak Sen’s All That Breathes, and Vinay Shukla’s While We Watched have faced challenges in funding as well as distribution within the country.

Watching Yugantar’s films makes one thing clear: an independently funded and produced film movement like Yugantar, that advocates for radical collective organizations that sustain mobilizing efforts of resistance, is essential today more than ever.

(Sudesha and Maid Servant will be screened at the Barbican Centre, London as part of the program on Indian parallel cinema—Rewriting the Rules: Pioneering Indian Cinema after 1970).

Four Decades Later, No City for Women Echoes the Enduring Impact of Yugantar Film Collective’s Path-Breaking Documentaries

At the end of Dr. Rangan Chakravarty’s documentary film No City for Women—a piercing look at modern day Gurgaon, its beginnings, and its growth into an unsafe concrete jungle—we see three women around a table. In the middle is the upper-class homeowner and employer living in one of the city’s ubiquitous gated communities. Two domestic workers, both women, are at her side. The interviewer behind the camera asks, “Is there a new mindset in Gurgaon?”

The woman on the right nods and explains how there is an expectation and demand for domestic workers who dress well (“pant-shirt wale”) and are smart and light-skinned. Their employer has a horrified look on her face. “To work?!” she exclaims. The woman on the right tells her, only half-jokingly, that one of her employer’s friends is among them. “Are you serious?” the employer responds. “Whisper her name to me!” The woman bursts into laughter but does not divulge.

No City for Women premiered in 2023 at Beyond Borders Feminist Film Festival held in New Delhi. The film is not about domestic workers—it looks, instead, at the larger plight of women navigating the unsafe city of Gurgaon. But the concerns of the domestic workers and working-class women in the film harks back to Molkarin (Maid Servant), one of several short documentaries made by Yugantar Film Collective in 1981.

Molkarin documents the protests and unionizing efforts of domestic workers in Pune, and their demand for rights and better working conditions. The film exposes not just the low wages of these workers, but also hostile treatment by employers, lack of holidays, and everyday casteism in the workplace.

About four decades separate Molkarin and No City for Women. In the intervening period, India has gone through several churns: from the rise of Hindutva, economic liberalization, and an endless wave of free market capitalism, to the present state of dictatorial democracy dominated by BJP’s Hindu right-wing government that actively works towards disenfranchising minorities.

India’s first feminist film collective, Yugantar was founded in 1980 by filmmakers and activists Deepa Dhanraj, Abha Bhaiya, Navroze Contractor, and Meera Rao in Bangalore. It was the first documentarian effort that highlighted feminist discourse, underlining caste and intersectionality that permeates social, political, and economic transactions in India.

The period of Yugantar’s foundation was an inchoate one of ideological shifts, since the country was coming to terms with the failure of the Nehruvian development model. It was marked by Indira Gandhi’s Emergency (1975-1977), which occurred with the nascent Naxalite movement, protests in Gujarat amidst an economic crisis, suppressed student movements in Bihar, and the quelled strike of the railway employees’ union. Movements like Nav Nirman saw women enter the protests in a big way, backed by the organizations they had formed. The post-Emergency period was colored by weary socialist leaders with neither drive nor popular support, and the opportunists who renewed their dreams for an India redrawn as a Hindu society.

It is a film movement that mirrored the reality of women entering public life in different roles and across demographics. Several women-led organizations came into their own for collective action during this period. For example, the Self-Employed Women’s Association was established as a trade union in Ahmedabad in 1972. Other women’s groups—like Progressive Organization of Women in Hyderabad, Stree Sangharsh, and Mahila Dakshata Samiti—came together for anti-dowry movements in the late 1970s.

Rooted in this time, the collective made four short documentaries between 1980 and 1983, filmed on 16mm, that captured an Indian society seldom given the privilege of image-making. Apart from Maid Servant, there are Tobacco Embers/Tambaku Chaakila Oob Ali (1982), Is This Just a Story/Idhi Katha Matramena (1983) and Sudesha (1983).

The documentaries blend fiction and non-fiction, with some rallying moments staged for recreation. In Maid Servant, Pune’s domestic workers form a union, Pune Shahar Molkarin Sanghatana (Pune City Domestic Workers Union), and express their righteous indignation at how poorly they are paid and treated. Their demands are not only just, but also sprawling: increase in wages, two holidays without pay cut, no pay cut if they go on leave, one month bonus, holidays for festivals, and no caste discrimination.

The last demand covers a gamut of societal issues—a domestic worker talks about how there are separate plates and glasses for them where they work. Blatant casteism is pervasive within the Indian middle and upper classes, and manifests in more nefarious ways today. Maid Servant also shows three generations of domestic workers in a family, all women, questioning why and how housework is traditionally considered women’s work and therefore undervalued.

In Sudesha, in the foothills of Himalayas far away from Maid Servant’s Pune, we meet Sudesha Devi who is an activist in the Chipko Movement fighting against deforestation and timber traders. Forestry remains their livelihood, and women carry the burden of the family. The film tracks Sudesha and other women working the fields, collecting bushes, crushing grains, cooking and cleaning at home, and routinely and sarcastically wondering if the men of the household will return for dinner. They are also active participants of the Chipko Movement, putting their bodies between the axe and the tree, for which they have been jailed. Sudesha mentions how, with the shrinking number of trees, every year they need to walk farther into the forest for firewood.

These films are not without the moments of levity. Like the woman pretending to be her drunk husband in Maid Servant, even Sudesha packs in tongue-in-cheek moments. The women declare that men can do nothing but plow—something the women can do themselves—and how their two weeks in jail was truly the best of times, as there was warm food, no work, and plenty of sleep.

More recently, No City for Women focuses heavily on Gurgaon’s gated communities: the upscale apartment complexes that are self-contained universes, with amenities for shopping as well as leisure. A resident jokes that a school inside is all that is needed. These gated communities are now present in every major city in India. Their proliferation has created two divergent worlds, one that is inside—insular, seemingly “safe” and disconnected—and the one that is outside, considered polluted and populated by the nebulous “other”, namely the working class, who the “insiders” view with disdain, disguised as fear.

Even within the “inside” world, these communities have separate elevators for gig and domestic workers, and mobile apps that control and surveil everyone’s entry and exit. The “inside” and the “outside” never mingle; this separation is desired. It creates a deeper class and caste divide that is more pronounced than the one we see in Maid Servant and Sudesha.

The Yugantar films from the early 1980s echo louder today, as the demands made by the domestic workers or the daily troubles of Sudesha sound almost quaint in 2024. Indian casteism has now made its way to diasporic communities abroad. Earlier this year, a Swiss court sentenced four members of the Hinduja family—one of the wealthiest families in the United Kingdom—to four years and six months in jail for trafficking and exploitation of their Indian domestic workers. State sponsored and endorsed targeting of minorities, coupled with violent suppression of dissenting voices, has emboldened the middle and upper classes in India to maintain their positions of power.

Yugantar began as an effort to separate documentary filmmaking from state funding, bringing it into the independent realm. This resulted in four important films that inspected fundamental fractures in Indian society, in which the subject-protagonists in front of the camera and the filmmaker-activists behind it were equal participants in a solidarity-building exercise.

Some of the sharpest political filmmaking in India today comes from documentaries. Yet, they lack reliable funding options and distribution networks, despite covering some of the most necessary stories. Films like Rintu Thomas and Sushmit Ghosh’s Writing with Fire, Payal Kapadia’s A Night of Knowing Nothing, Shaunak Sen’s All That Breathes, and Vinay Shukla’s While We Watched have faced challenges in funding as well as distribution within the country.

Watching Yugantar’s films makes one thing clear: an independently funded and produced film movement like Yugantar, that advocates for radical collective organizations that sustain mobilizing efforts of resistance, is essential today more than ever.

(Sudesha and Maid Servant will be screened at the Barbican Centre, London as part of the program on Indian parallel cinema—Rewriting the Rules: Pioneering Indian Cinema after 1970).

SUPPORT US

We like bringing the stories that don’t get told to you. For that, we need your support. However small, we would appreciate it.