Born in 1972, Nirmala Putul Murmu is many things: a distinguished poet, activist, and second-time Sarpanch or the village head in the local government of Kurwa Gram Panchayat, Dumka, Jharkhand. Writing in Santali and Hindi, her work transcends linguistic barriers and is translated into multiple languages, including English, Marathi, Russian, and Korean. She has been honored with prestigious awards like the Sahitya Akademi Prize for Translation and the Rashitrya Yuva Samman by the Sahitya Academy.

To paint an image of what Putul’s immediate residence and work landscape looks like, the Dumka district covers an area of 24.93 square kilometers in Jharkhand. Kurwa Panchayat includes three villages: Bagnocha with less than 5%, Karayachak Raghunathganj with 11-20%, and Kurwa with 76℅ above ST population as per the 2011 Census. The villages under this Panchayat barely have any government-built canals or artificial irrigation facilities to help the tribal farmers afford a year of full-blown cultivation.

As a result, the tribal and some chunks of the OBC population migrate inter and intra-state in search of livelihood opportunities. The official website of Dumka district holds the data on out-migrant laborers in the form of a 404-page PDF updated until 2020. This demonstrates a pattern in which the workers’ lowest educational qualification, both male and female, is illiteracy, while the highest qualification is a 10th pass.

In this interview, Putul talks about migration patterns, the reasons for migration, and a possible solution. She says that the tribal population owns cultivable land in Jharkhand, but due to the lack of any government-facilitated source of irrigation, good seeds, or fertilizers, they can harvest only one main crop a year and are unable to have a full-fledged cultivation year.

According to the data, the key sectors of work done by the migrant laborers include working at construction sites and brick kilns, as agriculture laborers, in rickshaw pulling, and as domestic workers. The Policy Brief Report which was commissioned by the Ministry of Tribal Affairs, Government of India, adds, “There are various reasons that force tribals to migrate in places where they land up for economic succor. Almost 80% of the tribal population is rural and is mostly dependent on agriculture for livelihood. However, the status of lands and irrigation available in those lands dissuades any form of sustainable agriculture. This makes agriculture a possibility for them only in the few months of monsoon.”

Another study by Jharkhand Anti Trafficking Network (JATN) that included Kurwa Panchayat found out, “After the November harvest, livestock-rearing, and manual labor in the village and nearby Government schemes were the main sources of livelihood in the village. The rate of migration for ST households was higher in comparison to other groups.”

Recently, Kurwa Panchayat has been selected as ‘Mahila Hitaesi Panchayat’ by the Central Government. The central government has planned to choose one such Panchayat from every district; these panchayats are meant to serve as an ideal to ensure gender equality and implement existing policies and schemes in a way that combat against gender discrimination. However, Nirmala Putul Murmu does not seem very hopeful about these announcements. She often faces bureaucratic hurdles whenever she tries to work for the people of her Panchayat.

When asked about her tenure achievements, she gives a non-statistical answer that shows the tiredness and determination of a grassroots worker: “I do not know what to say, I do not want to quote a data of my achievement, there is no such ‘achievement’, I just want to work for my people until all their rights are served.”

Being an Adivasi herself, Putul’s poems are living evidence of all the grassroots realities that appear mundane in their tone but are very much socio-political, like witch-hunting of women, appropriation of Adivasi women’s bodies by the non-Adivasi gaze, and several others. Her work engages the readers both emotionally and intellectually. She writes from the particulars of who she is: a woman, an Adivasi person, a resident of Jharkhand, and a mother figure to many. Such an epistemic positioning makes her poetry a strong voice of resilience and struggle against gender discrimination and cultural assertion.

Putul sheds light on challenges faced by Adivasi women selling hadiya (rice beer), the hardships and the plight of left-behind wives of migrants, and the complex issue of property rights for Adivasi women.

What follows is an edited and translated excerpt from our conversation.

AA: Nirmala Ji, you have said that your poems are the byproduct of your surroundings and grassroots engagement. Please walk us through your experience working with Adivasi and Diku communities in Jharkhand.

NPM: I have been an activist even before I stepped into the literary world. I am a Santhal woman. I come from the Adivasi community, therefore I have seen their lives very closely. Simultaneously, working with nonprofits, I am very well connected to the Diku (non-Adivasi) community around me. During my field trips to the villages, I witnessed the daily lives of people who would talk to me about their issues. I then started documenting my observations in the form of case studies. My poems were born from these everyday notes.

People recognized my work as poetry. Some thought they were case studies as well as poetry. I also pondered: I am an Adivasi, and if my work is a reflection of our lives, why not? Until then, I did not know much about the literary world, what qualifies as a poem, and other paraphernalia. However, when I began writing, I knew both Hindi and Santhali, and this worked in my favor.

Slowly, I realized that my work is a relevant part of the poetry milieu. I gained confidence after being published. My work began to earn encouragement and recognition from my contemporaries and readers.

AA: Were the field visits and grassroots work that you did back then through any NGO, or was it on an individual basis? What connected you to the nonprofits?

NPM: I always used to work for the community in my personal capacity. Meeting people from my own community and other communities, talking to them about their issues, and supporting them has been my constant agenda. However, you know, after a point, one wonders how one can make oneself financially stronger. One needs money even to step outside of one’s house and work for society.

Through my friends, I came to know about NGOs and some of them work for women’s issues. ‘Badlaav Foundation’ was the first such NGO I worked with, then I worked with ‘Lok Chirag Seva Sansthan’. The NGOs served as a medium for me to reach people, and become more equipped with factual information.

I closely observed the state of women in the villages I worked in: What are their desires? To what extent are they able to fulfill those desires? What is their position inside the family, community, and society? Are they able to exercise their constitutional rights? I found that the women are very naive, many times they are unable to identify the oppression that they are subjugated to.

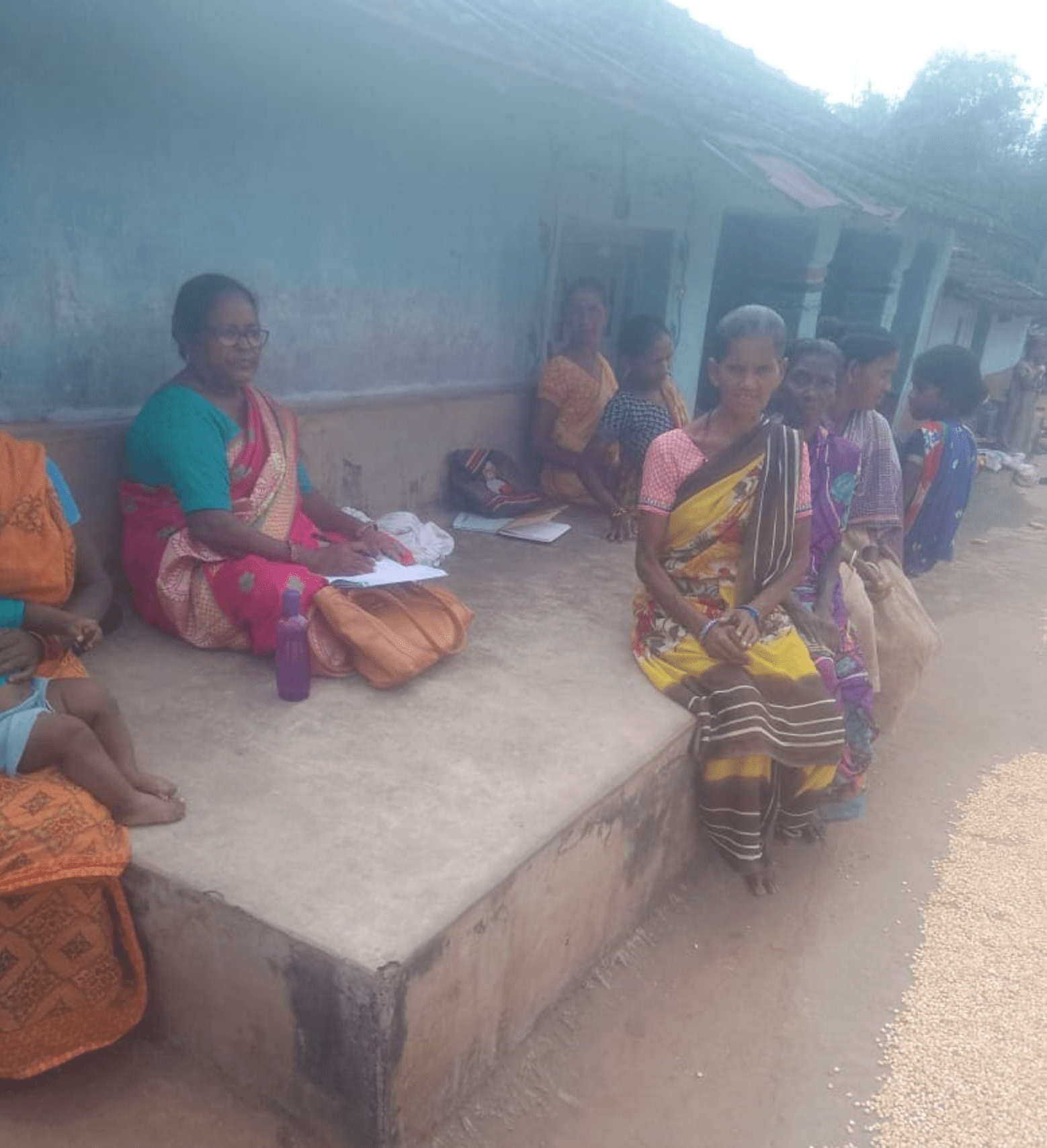

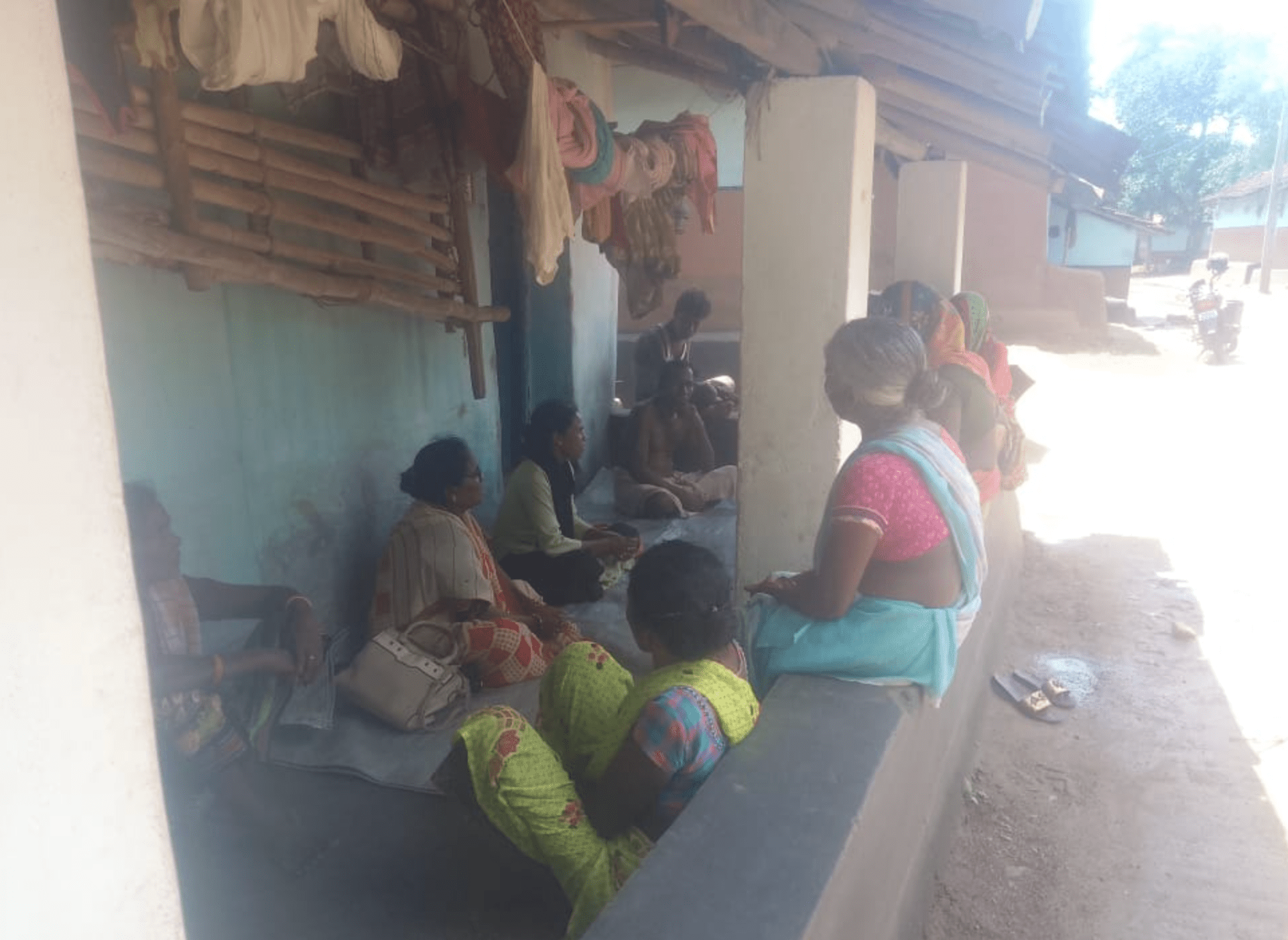

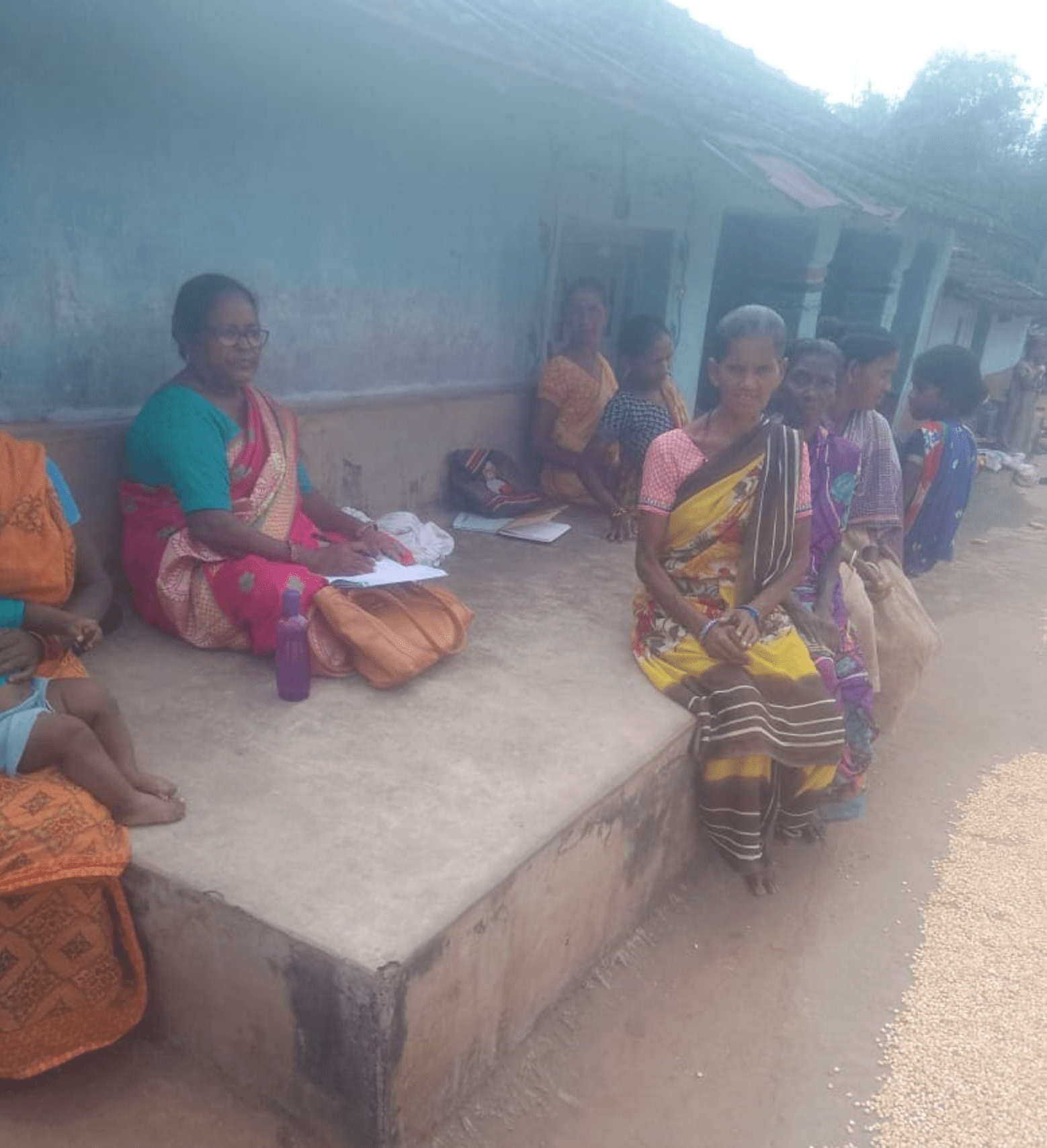

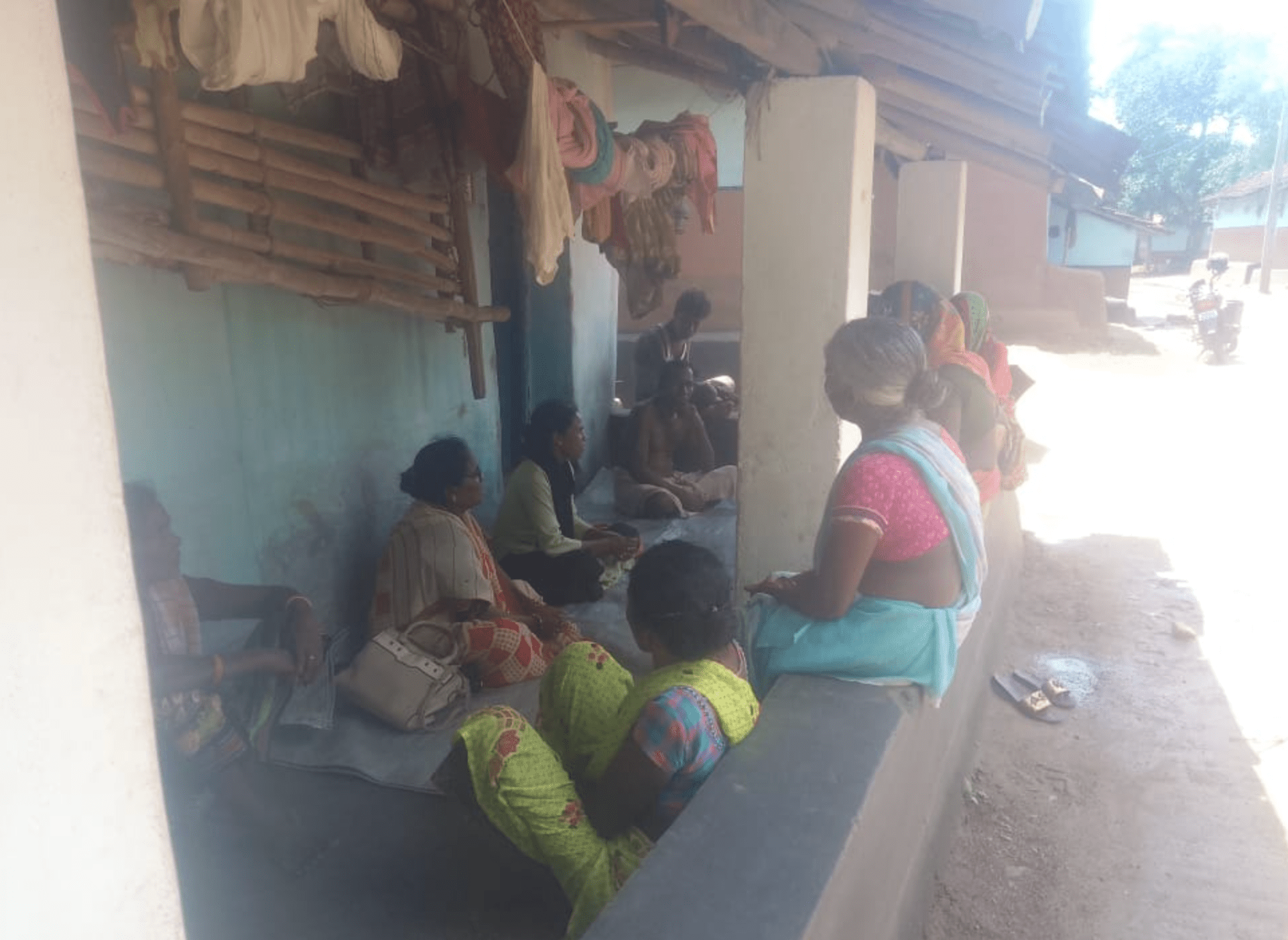

During my interactions with the women in awareness meetings, we got a chance to exchange our experiences. I got an inside peek into their lives, their problems, and the reasons why these problems continue to exist. These incidents strengthened my faith in the rights of women that they were actually denied. It is necessary to make them aware of their rights. I used our meetings as a platform to create awareness amongst the women.

AA: What rights-based areas did you work for?

NPM: In tribal societies, women do not have rights over property. Due to this, they are ‘landless’. Even in the courtyards of their houses, they are not given respect by their families or they are exploited by their husbands. So, I thought: why not have the right to property for Adivasi women? I thought, suppose she marries and goes to her husband’s house, then after marriage whatever piece of land the husband owns, I wanted the woman’s name to also be registered in there. She must also have her share in the husband’s land.

This means they will have some land of their own, in their name. Right to land hence is a very effective step to empower them with a sense of rights and a claim. With this idea, along with other activists, I started working to spread awareness among women. We started telling them that rights are something that one cannot beg for, one has to fight for it, struggle for it.

Along with it, I worked for the right to education. I made a lot of impact working with government schools to ensure students’ engagement, mid-day meals, distribution of stationary, etc.

If the children are educated, as adults, they can talk about their rights.

AA: What are the stereotypes around Adivasi women to justify their lack of land rights?

NPM: It is falsely rumored and stereotyped that if a woman gets any piece of the land, she will sell it, someone will woo her and manipulate her for the land, or if she marries another caste man, the land will be lost. Yet, all the lands that are sold to the outsiders are sold by men. Women are not selling those lands. They do not have any ownership over land and most often not on the decision regarding men selling the family lands.

Now the women, who are also wives, become left-behind wives when the husband migrates and leaves the home. When the husband migrates [for work], the women who are left behind work hard, take care of the in-laws, kids, and the household, and also work outside. She is responsible and understands life, so the stereotypes are baseless. Women should have land rights.

In this way, if the husband wants to sell the land the wife will also have a say in it.

AA: How do the issues facing women and children in Adivasi society compare to those in Diku society?

NPM: In my experience, women in Adivasi society and Diku society are struggling in similar ways. The difference is that we Adivasi women are beaten on the streets and those women are beaten inside the house––on the doorstep, in the kitchen, on the bed.

Even if an Adivasi or OBC woman wants to escape their situation, she does not have the money to get her children educated in a big school. Children mostly go to the government school and you already know what arrangements are made in a government school. Many teachers are not even present, and most of the students still roam around outside. So these are the problems of both women and children, of both Adivasi and OBC groups here.

AA: In your Panchayat (Kurwa), what is the population ration of Upper castes, OBCs, and Adivasis? What are their means of livelihood?

NPM: The Savarna are less in number here; more are the OBCs, however, somehow Savarnas continue to maintain power over Adivasis and the OBCs here.

Now, how do they (Adivasis and OBCs) manage the economic issues of their society and tribal society? We have seen men waking up early, heading out around three or four in the morning to make a living. They gather their goods at the market, where large trucks bring in supplies such as bricks, iron rods, and cement from other places. After unloading these materials and delivering them to the owners, they return home by nine or ten o’clock. Both Adivasi men and Diku men (OBCs) from this area set off together at these early hours, starting their day’s work side by side.

When the men return, the women of the houses wake up at seven or eight in the morning and then go to work in other people’s homes as domestic workers. Women contribute to the household, they take care of the kids as well as daily household expenses.

So, one cannot say that their financial condition is very good, they can hardly get two meals a day and nothing more than that. But now, the government is paying attention but is also giving it for its own selfish agenda, like to get votes, then schemes like Maiya Samman Yojana or Gogo Didi Yojana Samman are announced. Now people run around to fill out the forms for government schemes. I have observed all this as a Mukhiya. However, they rarely benefit.

Since they are now getting rice from the government right now, they get a little support from that. But if they fall ill and need help from a doctor, they go on loans and debts for this. I have seen many families suffer like this.

AA: What other main source of income exists for Adivasi women?

NPM: They sell liquor, and their men go out to earn money in Bengal or Assam. They go out to earn money, but women will not migrate outside of the state to work in the labor market. At most, she will work at someone’s house as a domestic worker, and if not, she will sell liquor in the nearby market area.

AA: How can we combat the stigmatization and exploitation of women selling hadiya in the market?

NPM: In our culture, hadiya is consumed as a drink and it is also used in worship as an offering to the gods. Yes, without hadiya, even the gods are not happy. That is why you will see that at every festival, it is made at home. Another important thing is that our people have seen that liquor also generates income. So because of that, along with drinking it, they also connect it with their self-employment.

What I mean by “self-employment” is that in the market, when people are given licenses to sell other kinds of liquor like bideshi sharab, then why when we, the Adivasis, sell liquor, we are called wrong or stigmatized? The government gives licenses to others to sell liquor and when we sell it, the police arrest us. So why this double standard?

Now if the government wants to empower the Adivasi people, there should be fewer hindrances for them to access the government schemes. They will not give the scheme benefits to them easily; there are many kinds of complications. People do not want to get into those hassles and delays.

Even when the government wants to help, it does not want us to be empowered fully; rather it wants the public to always extend their palms towards the government. They keep giving them bread in pieces. This is their subtle strategy to ensure that vote bank politics remains.

AA: We have reports about the exploitation of domestic workers. How frequently does this occur in that area? And how is this exploitation commonly seen in everyday life?

NPM: The employers want cheap labor. Women– who are domestic workers– are made to work for more hours than required. The wages she gets are very low in comparison to the labour she puts in and the working conditions are bad. If she cannot reach on time for a few days or is absent due to her situation, the employer fires them without much consideration. If she worked as a laborer, she would get daily wages, but as a domestic worker, she cannot earn even Rs. 100 per day. This is exploitation. This is a violation of rights and constitutional rights, isn’t it?

The thinking of the upper caste people is exploitative. If an upper caste employer gives some monetary help to the workers, they feel the domestic workers owe them a lifetime favor. If they help the worker once, they will keep them in their clutches for the rest of their lives.

So, this is the kind of thinking of the upper caste people here: they control the Adivasis using manipulation. Their gaze gestures that they are superior to them. This behavioral pattern is very much part of the mundane life here. Like, the upper castes pass some rugs to the Adivasi workers to sit on [the floor] and this is acceptable as the norm. Many times, even the Adivasi women who come to me sit on the floor. I urge them to sit on the chairs. I am from the same community and so I know how their self-respect is killed. I feel their pain. The erasure of self-respect is internalized within the oppressed. At least I can help them see themselves with a sense of dignity and acknowledge their own struggles.

AA: How does migration impact the residents of your Panchayat and what could be proposed as a solution?

NPM: Migration has many [adverse] impacts on left-behind wives/women. They are more prone to unwanted sexual gaze from other men.

Adivasis here have land, they engage in farming. Due to a lack of good seeds, fertilizers, and water for irrigation, the land is not useful for agriculture most times of the year. People here are dependent on rainwater for harvesting, but the months with no rain are useless to us. The government ought to make policies and implementations to ensure that people can practice 12 months of farming. Seeds and fertilizers provided by the government do not reach the people. They are consumed by corruption. If the proper way of farming is ensured it can be used as a method to tackle migration. In a household both the husband and wife can engage in farming. Even if they migrate then, the reason would not be to meet the bare minimum basic needs but to ensure a better life. We expect the government to solve these problems.

AA: You served as Mukhiya from 2015-2020 in the First tenure. How is the second tenure going for you?

NPM: This position gives me more access to knowledge, political scenarios, experiences, and people. I can study and analyze society more closely. It helps me with my writing. I would always like to be a part of public life. I also face challenges, but the people’s belief acts as my strength. I sort things out in Panchayat-level women groups, which strengthens my willpower. 60,000-70,000 people whom I represent trust me. Sometimes administrative pressure makes things difficult, but one has to deal with them. I always think, my people support me.

Related Posts

Nirmala Putul on Poetry, Practice, and Adivasi Rights

Born in 1972, Nirmala Putul Murmu is many things: a distinguished poet, activist, and second-time Sarpanch or the village head in the local government of Kurwa Gram Panchayat, Dumka, Jharkhand. Writing in Santali and Hindi, her work transcends linguistic barriers and is translated into multiple languages, including English, Marathi, Russian, and Korean. She has been honored with prestigious awards like the Sahitya Akademi Prize for Translation and the Rashitrya Yuva Samman by the Sahitya Academy.

To paint an image of what Putul’s immediate residence and work landscape looks like, the Dumka district covers an area of 24.93 square kilometers in Jharkhand. Kurwa Panchayat includes three villages: Bagnocha with less than 5%, Karayachak Raghunathganj with 11-20%, and Kurwa with 76℅ above ST population as per the 2011 Census. The villages under this Panchayat barely have any government-built canals or artificial irrigation facilities to help the tribal farmers afford a year of full-blown cultivation.

As a result, the tribal and some chunks of the OBC population migrate inter and intra-state in search of livelihood opportunities. The official website of Dumka district holds the data on out-migrant laborers in the form of a 404-page PDF updated until 2020. This demonstrates a pattern in which the workers’ lowest educational qualification, both male and female, is illiteracy, while the highest qualification is a 10th pass.

In this interview, Putul talks about migration patterns, the reasons for migration, and a possible solution. She says that the tribal population owns cultivable land in Jharkhand, but due to the lack of any government-facilitated source of irrigation, good seeds, or fertilizers, they can harvest only one main crop a year and are unable to have a full-fledged cultivation year.

According to the data, the key sectors of work done by the migrant laborers include working at construction sites and brick kilns, as agriculture laborers, in rickshaw pulling, and as domestic workers. The Policy Brief Report which was commissioned by the Ministry of Tribal Affairs, Government of India, adds, “There are various reasons that force tribals to migrate in places where they land up for economic succor. Almost 80% of the tribal population is rural and is mostly dependent on agriculture for livelihood. However, the status of lands and irrigation available in those lands dissuades any form of sustainable agriculture. This makes agriculture a possibility for them only in the few months of monsoon.”

Another study by Jharkhand Anti Trafficking Network (JATN) that included Kurwa Panchayat found out, “After the November harvest, livestock-rearing, and manual labor in the village and nearby Government schemes were the main sources of livelihood in the village. The rate of migration for ST households was higher in comparison to other groups.”

Recently, Kurwa Panchayat has been selected as ‘Mahila Hitaesi Panchayat’ by the Central Government. The central government has planned to choose one such Panchayat from every district; these panchayats are meant to serve as an ideal to ensure gender equality and implement existing policies and schemes in a way that combat against gender discrimination. However, Nirmala Putul Murmu does not seem very hopeful about these announcements. She often faces bureaucratic hurdles whenever she tries to work for the people of her Panchayat.

When asked about her tenure achievements, she gives a non-statistical answer that shows the tiredness and determination of a grassroots worker: “I do not know what to say, I do not want to quote a data of my achievement, there is no such ‘achievement’, I just want to work for my people until all their rights are served.”

Being an Adivasi herself, Putul’s poems are living evidence of all the grassroots realities that appear mundane in their tone but are very much socio-political, like witch-hunting of women, appropriation of Adivasi women’s bodies by the non-Adivasi gaze, and several others. Her work engages the readers both emotionally and intellectually. She writes from the particulars of who she is: a woman, an Adivasi person, a resident of Jharkhand, and a mother figure to many. Such an epistemic positioning makes her poetry a strong voice of resilience and struggle against gender discrimination and cultural assertion.

Putul sheds light on challenges faced by Adivasi women selling hadiya (rice beer), the hardships and the plight of left-behind wives of migrants, and the complex issue of property rights for Adivasi women.

What follows is an edited and translated excerpt from our conversation.

AA: Nirmala Ji, you have said that your poems are the byproduct of your surroundings and grassroots engagement. Please walk us through your experience working with Adivasi and Diku communities in Jharkhand.

NPM: I have been an activist even before I stepped into the literary world. I am a Santhal woman. I come from the Adivasi community, therefore I have seen their lives very closely. Simultaneously, working with nonprofits, I am very well connected to the Diku (non-Adivasi) community around me. During my field trips to the villages, I witnessed the daily lives of people who would talk to me about their issues. I then started documenting my observations in the form of case studies. My poems were born from these everyday notes.

People recognized my work as poetry. Some thought they were case studies as well as poetry. I also pondered: I am an Adivasi, and if my work is a reflection of our lives, why not? Until then, I did not know much about the literary world, what qualifies as a poem, and other paraphernalia. However, when I began writing, I knew both Hindi and Santhali, and this worked in my favor.

Slowly, I realized that my work is a relevant part of the poetry milieu. I gained confidence after being published. My work began to earn encouragement and recognition from my contemporaries and readers.

AA: Were the field visits and grassroots work that you did back then through any NGO, or was it on an individual basis? What connected you to the nonprofits?

NPM: I always used to work for the community in my personal capacity. Meeting people from my own community and other communities, talking to them about their issues, and supporting them has been my constant agenda. However, you know, after a point, one wonders how one can make oneself financially stronger. One needs money even to step outside of one’s house and work for society.

Through my friends, I came to know about NGOs and some of them work for women’s issues. ‘Badlaav Foundation’ was the first such NGO I worked with, then I worked with ‘Lok Chirag Seva Sansthan’. The NGOs served as a medium for me to reach people, and become more equipped with factual information.

I closely observed the state of women in the villages I worked in: What are their desires? To what extent are they able to fulfill those desires? What is their position inside the family, community, and society? Are they able to exercise their constitutional rights? I found that the women are very naive, many times they are unable to identify the oppression that they are subjugated to.

During my interactions with the women in awareness meetings, we got a chance to exchange our experiences. I got an inside peek into their lives, their problems, and the reasons why these problems continue to exist. These incidents strengthened my faith in the rights of women that they were actually denied. It is necessary to make them aware of their rights. I used our meetings as a platform to create awareness amongst the women.

AA: What rights-based areas did you work for?

NPM: In tribal societies, women do not have rights over property. Due to this, they are ‘landless’. Even in the courtyards of their houses, they are not given respect by their families or they are exploited by their husbands. So, I thought: why not have the right to property for Adivasi women? I thought, suppose she marries and goes to her husband’s house, then after marriage whatever piece of land the husband owns, I wanted the woman’s name to also be registered in there. She must also have her share in the husband’s land.

This means they will have some land of their own, in their name. Right to land hence is a very effective step to empower them with a sense of rights and a claim. With this idea, along with other activists, I started working to spread awareness among women. We started telling them that rights are something that one cannot beg for, one has to fight for it, struggle for it.

Along with it, I worked for the right to education. I made a lot of impact working with government schools to ensure students’ engagement, mid-day meals, distribution of stationary, etc.

If the children are educated, as adults, they can talk about their rights.

AA: What are the stereotypes around Adivasi women to justify their lack of land rights?

NPM: It is falsely rumored and stereotyped that if a woman gets any piece of the land, she will sell it, someone will woo her and manipulate her for the land, or if she marries another caste man, the land will be lost. Yet, all the lands that are sold to the outsiders are sold by men. Women are not selling those lands. They do not have any ownership over land and most often not on the decision regarding men selling the family lands.

Now the women, who are also wives, become left-behind wives when the husband migrates and leaves the home. When the husband migrates [for work], the women who are left behind work hard, take care of the in-laws, kids, and the household, and also work outside. She is responsible and understands life, so the stereotypes are baseless. Women should have land rights.

In this way, if the husband wants to sell the land the wife will also have a say in it.

AA: How do the issues facing women and children in Adivasi society compare to those in Diku society?

NPM: In my experience, women in Adivasi society and Diku society are struggling in similar ways. The difference is that we Adivasi women are beaten on the streets and those women are beaten inside the house––on the doorstep, in the kitchen, on the bed.

Even if an Adivasi or OBC woman wants to escape their situation, she does not have the money to get her children educated in a big school. Children mostly go to the government school and you already know what arrangements are made in a government school. Many teachers are not even present, and most of the students still roam around outside. So these are the problems of both women and children, of both Adivasi and OBC groups here.

AA: In your Panchayat (Kurwa), what is the population ration of Upper castes, OBCs, and Adivasis? What are their means of livelihood?

NPM: The Savarna are less in number here; more are the OBCs, however, somehow Savarnas continue to maintain power over Adivasis and the OBCs here.

Now, how do they (Adivasis and OBCs) manage the economic issues of their society and tribal society? We have seen men waking up early, heading out around three or four in the morning to make a living. They gather their goods at the market, where large trucks bring in supplies such as bricks, iron rods, and cement from other places. After unloading these materials and delivering them to the owners, they return home by nine or ten o’clock. Both Adivasi men and Diku men (OBCs) from this area set off together at these early hours, starting their day’s work side by side.

When the men return, the women of the houses wake up at seven or eight in the morning and then go to work in other people’s homes as domestic workers. Women contribute to the household, they take care of the kids as well as daily household expenses.

So, one cannot say that their financial condition is very good, they can hardly get two meals a day and nothing more than that. But now, the government is paying attention but is also giving it for its own selfish agenda, like to get votes, then schemes like Maiya Samman Yojana or Gogo Didi Yojana Samman are announced. Now people run around to fill out the forms for government schemes. I have observed all this as a Mukhiya. However, they rarely benefit.

Since they are now getting rice from the government right now, they get a little support from that. But if they fall ill and need help from a doctor, they go on loans and debts for this. I have seen many families suffer like this.

AA: What other main source of income exists for Adivasi women?

NPM: They sell liquor, and their men go out to earn money in Bengal or Assam. They go out to earn money, but women will not migrate outside of the state to work in the labor market. At most, she will work at someone’s house as a domestic worker, and if not, she will sell liquor in the nearby market area.

AA: How can we combat the stigmatization and exploitation of women selling hadiya in the market?

NPM: In our culture, hadiya is consumed as a drink and it is also used in worship as an offering to the gods. Yes, without hadiya, even the gods are not happy. That is why you will see that at every festival, it is made at home. Another important thing is that our people have seen that liquor also generates income. So because of that, along with drinking it, they also connect it with their self-employment.

What I mean by “self-employment” is that in the market, when people are given licenses to sell other kinds of liquor like bideshi sharab, then why when we, the Adivasis, sell liquor, we are called wrong or stigmatized? The government gives licenses to others to sell liquor and when we sell it, the police arrest us. So why this double standard?

Now if the government wants to empower the Adivasi people, there should be fewer hindrances for them to access the government schemes. They will not give the scheme benefits to them easily; there are many kinds of complications. People do not want to get into those hassles and delays.

Even when the government wants to help, it does not want us to be empowered fully; rather it wants the public to always extend their palms towards the government. They keep giving them bread in pieces. This is their subtle strategy to ensure that vote bank politics remains.

AA: We have reports about the exploitation of domestic workers. How frequently does this occur in that area? And how is this exploitation commonly seen in everyday life?

NPM: The employers want cheap labor. Women– who are domestic workers– are made to work for more hours than required. The wages she gets are very low in comparison to the labour she puts in and the working conditions are bad. If she cannot reach on time for a few days or is absent due to her situation, the employer fires them without much consideration. If she worked as a laborer, she would get daily wages, but as a domestic worker, she cannot earn even Rs. 100 per day. This is exploitation. This is a violation of rights and constitutional rights, isn’t it?

The thinking of the upper caste people is exploitative. If an upper caste employer gives some monetary help to the workers, they feel the domestic workers owe them a lifetime favor. If they help the worker once, they will keep them in their clutches for the rest of their lives.

So, this is the kind of thinking of the upper caste people here: they control the Adivasis using manipulation. Their gaze gestures that they are superior to them. This behavioral pattern is very much part of the mundane life here. Like, the upper castes pass some rugs to the Adivasi workers to sit on [the floor] and this is acceptable as the norm. Many times, even the Adivasi women who come to me sit on the floor. I urge them to sit on the chairs. I am from the same community and so I know how their self-respect is killed. I feel their pain. The erasure of self-respect is internalized within the oppressed. At least I can help them see themselves with a sense of dignity and acknowledge their own struggles.

AA: How does migration impact the residents of your Panchayat and what could be proposed as a solution?

NPM: Migration has many [adverse] impacts on left-behind wives/women. They are more prone to unwanted sexual gaze from other men.

Adivasis here have land, they engage in farming. Due to a lack of good seeds, fertilizers, and water for irrigation, the land is not useful for agriculture most times of the year. People here are dependent on rainwater for harvesting, but the months with no rain are useless to us. The government ought to make policies and implementations to ensure that people can practice 12 months of farming. Seeds and fertilizers provided by the government do not reach the people. They are consumed by corruption. If the proper way of farming is ensured it can be used as a method to tackle migration. In a household both the husband and wife can engage in farming. Even if they migrate then, the reason would not be to meet the bare minimum basic needs but to ensure a better life. We expect the government to solve these problems.

AA: You served as Mukhiya from 2015-2020 in the First tenure. How is the second tenure going for you?

NPM: This position gives me more access to knowledge, political scenarios, experiences, and people. I can study and analyze society more closely. It helps me with my writing. I would always like to be a part of public life. I also face challenges, but the people’s belief acts as my strength. I sort things out in Panchayat-level women groups, which strengthens my willpower. 60,000-70,000 people whom I represent trust me. Sometimes administrative pressure makes things difficult, but one has to deal with them. I always think, my people support me.

SUPPORT US

We like bringing the stories that don’t get told to you. For that, we need your support. However small, we would appreciate it.