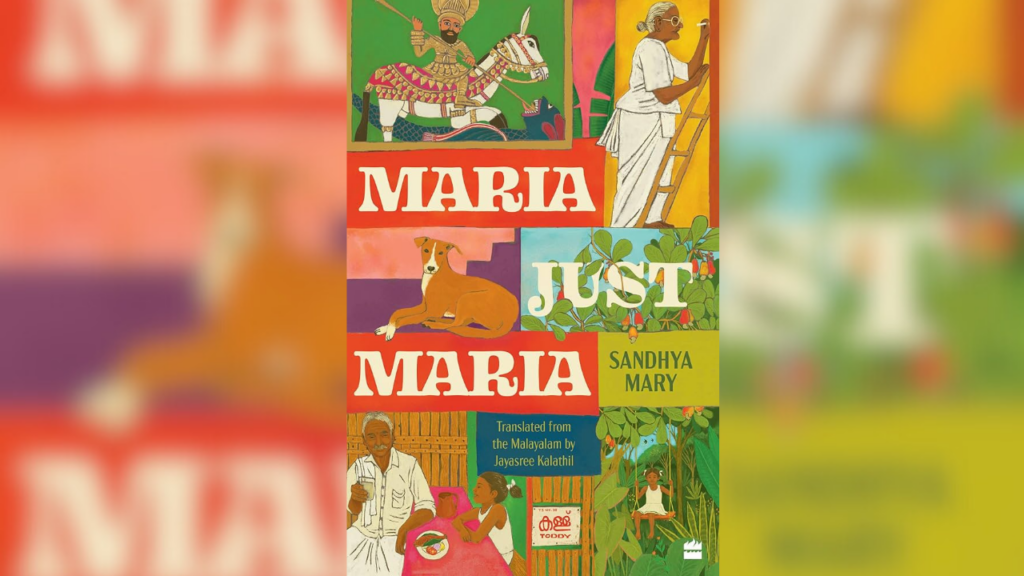

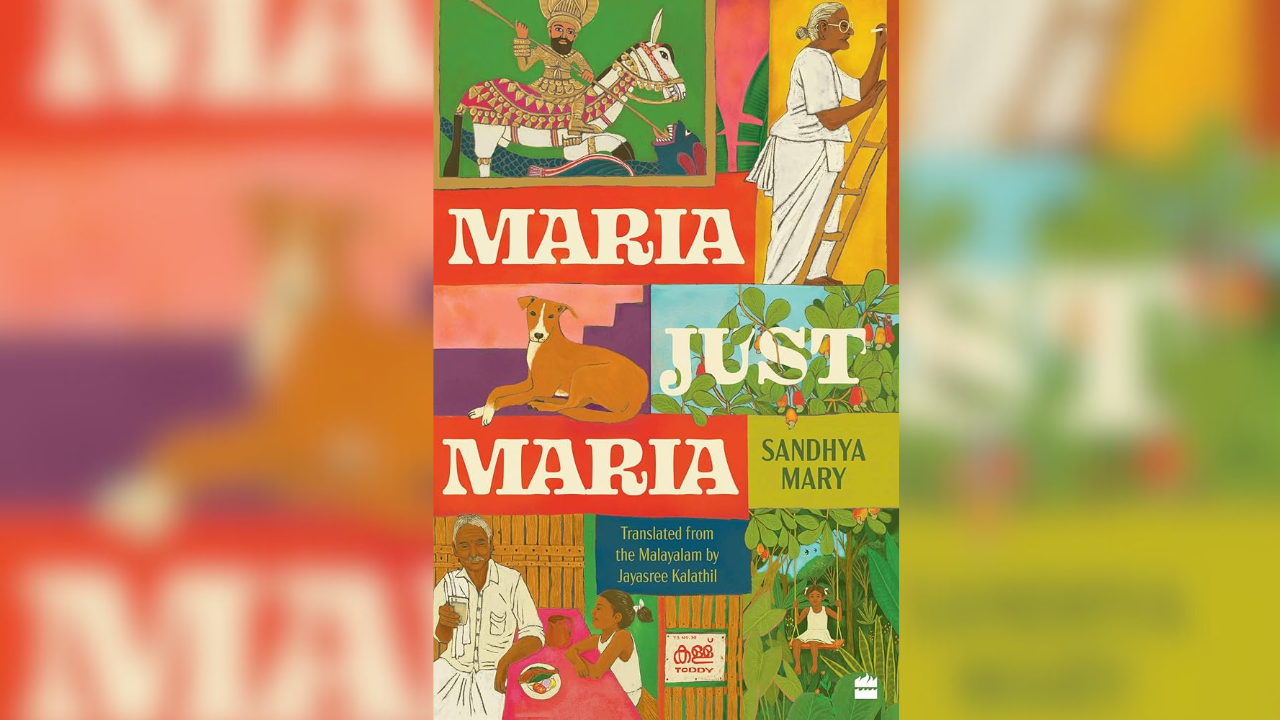

Sandhya Mary’s Maria, Just Maria challenges the construct of normalcy by centering a seemingly mad woman as its unabashed protagonist.

Originally published in Malayalam in 2018, the novel was translated into English in 2024 by Jayasree Kalathil. Even in translation, Maria, Just Maria reads like the swirling, coiling letters of Malayalam due to its non-linear narrative structure, magical realist elements, and multiple “mad” characters. Yet, what distinguishes Mary’s novel is not its literary peculiarities, but the mere existence of a narrative voiced by a woman deemed mad by society.

Maria, Just Maria begins in a psychiatric hospital where, according to the doctors, Maria was admitted for exhibiting abnormal tendencies such as “giving up speaking.” But as is always the case, what men in power claim is only half the truth. Hence, while the narrative begins and ends in a psychiatrist’s hospital, the period in between is filled with Maria’s attempt at telling her own tale in her own way.

As Salman Rushdie observes in his famed novel Midnight’s Children (1981), you must swallow the whole world to understand just one life. In the same vein, Maria draws her imagined readers into her Kottarathil Veedu (her ancestral home) and compels them to witness the intricate lives of the four generations who lived and died before she was born with an inherited madness and a remarkably furious look on her face. Maria’s childhood is spent philosophizing with a talking dog and visiting toddy shops with her grandfather Geevarghese.

As she grows older, she resurrects dead ancestors to wander about in the astral plane and conjures up a Jesus Christ who learns from her colloquial Malayalam words such as dookly (loosely meaning “second-rate”). Maria, Just Maria does not follow the usual rising and falling action; instead, it is scattered with fragmented glimpses into the lives of the people who surround Maria as she gradually untangles her “mad” world. In the self-reflexive ending of the novel, she is back in her hospital room, pondering on the other possible ways she could end the book that she is planning to write (but has, in reality, already written), leaving the readers to wonder whether Maria is truly mad and if so, who determines the boundaries between sanity and madness?

Through a bleak, satirical tone and a deliberately disorganized narrative style, Maria, Just Maria calls for a deconstruction of the normal-abnormal binary, further situating it as the only way for the liberation of women.

What Is “Normal”?

The most radical lines in Maria, Just Maria come from a canine mouth. When Maria tries to educate her dog, Chandipatti, about color blindness in dogs, he repudiates, “Has any dog ever gone to a scientist and told them [that] it is color blindness?… Who are you humans to make these decisions for us?” Maria (and her dog) often makes the reader question their own grip on reality.

Throughout Maria, Just Maria, Mary presents a variety of characters—some labeled “mad” and some not—and ultimately reveals that they are fundamentally the same; they simply fall somewhere on the vast spectrum of being human. Maria’s friend, Vinayakan, who transitions from a great chess player to a “madman” on the street is no more or less normal than her lover, Aravind, who longs for Maria’s commitment despite her resistance.

While reflecting on the world’s relationship with madness, Maria argues that “real life is boring but madness might add a bit of interest to it” and quickly follows it with a realization that both are terribly boring. She declares that madness is not extreme; it is normal, unremarkable, and ultimately, boring.

Maria, Just Maria thus highlights that much like the notion of gender, the construct of normalcy and disability is social— and not, contrary to popular belief, totally biological. The instinct to attribute synonyms of lunacy to anyone whose actions fall outside one’s personal—and hence, limiting—comprehension exposes the arbitrary and subjective nature of such a classification.

It arises from an ableist and phallocentric authority that conveniently categorizes the marginals as “abnormal:” a woman who transgresses the male gaze, a man who exhibits femininity, or a trans person who simply exists. Society does not shy away from branding them as “crazy deviants.”

Similarly, what appears as madness for the other characters is, for Maria, simply her authentic nature unscathed by societal molding. As the author-translator conversation in Maria, Just Maria’s postscript also suggests, her madness is not a fixed pathological category but a fluid and relative label.

Rethinking Female Hysteria

Sandhya Mary’s madwoman stands in stark contrast to the quintessential madwoman of the literary canon who is presented as a beastly figure with disheveled hair and animalistic teeth lurking in the shadow of the moral, ideal, “normal” hero. From Ophelia in the river in Shakespeare’s Hamlet (1623) to Bertha Mason in the attic in Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre (1847), womanhood and hysteria have been linked like a sordid two-for-the-price-of-one deal.

While the binary of male rationality versus female insanity has been pervasive across both geographical and temporal distances, its origins can be traced down to the very etymology of the term. Hysteria originates from the Greek word for uterus, a faulty association undoubtedly made by those who did not possess the organ they claimed to know.

As a result, most narratives that employ the mad woman trope do so to evoke fascination, horror, and at times, pity in their readers, all of which are emotions that arise out of a supremacist attitude. In Maria, Just Maria, however, these emotions appear on the side of the madwoman—she is fascinated and horrified at the world’s reaction to nonconformity.

Since Maria is thrust outside the claustrophobic category of a “normal” woman, she acquires a place beyond the patriarchal rules that have always governed her kind. As a woman deemed “not quite right in the head,” she exercises a considerable degree of agency that allows her to voice radical ideas—on topics such as marriage and divorce, traditional gender roles, and limitations of educational systems—even if they oppose the rigid standards of society.

“Madness” as Agency

While Maria does not overtly exhibit feminist consciousness, the author uses the character to explore ideas that transcend global gender studies theories. When Maria’s “unwomanly” behavior—such as eating food off the floor, a desire to harm her bullying sister and her candid and offensive speech—land her in a psychiatrist’s office, what he prescribes for her is not counseling that can aid him in understanding her home environment better but a guidebook about a “well-behaved girl.”

Maria’s perceived insanity may have granted her a certain freedom to at best, reject conventional gender roles—or at worst, be perceived as selfish. Yet the very fact that such a rejection has to be classified as “insanity” is what remains most unsettling. As Elaine Showalter noted in The Female Malady (1987), insanity has historically been a penalty label for being a woman, or worse, for desiring or daring not to be.

By the end of Maria, Just Maria, it becomes evident that Maria ends up in the psychiatric hospital because she is authentic, rebellious, distinct, and most importantly, a woman unpoliced by society. From the witches of Salem to the feisty activists of today, history has made one thing clear: a woman left to her own devices is dangerous and hence must be promptly crushed.

Thus, with a flexible narrative and an uncompromising candid narrator, Maria, Just Maria links madness with agency; the mad woman ceases to be the “suppressed Other” and rises as a feminist figure. However, as Maria languishes in a psychiatric hospital, all alone with only her “mad thoughts” to keep her company, it becomes apparent that her agency and voice have come at the cost of social alienation. She is isolated, and at one point yearns to talk to someone, but finds none of her people around.

The madwoman’s attic is ultimately inescapable, her agency is turned into a pseudo-agency; after all, what freedom can one have locked up in a hospital ward? Pertinent questions such as these pervade the text: why must Maria’s unabashed selfhood be branded as madness? Is madness the only way out for a woman from patriarchy’s clutches? And if so, is such a freedom worth the fight?

While it picks apart social conventions surrounding gender, disability, and normalcy, Maria, Just Maria ultimately suggests that a woman can find true freedom perhaps only in a mad, mad world.

Related Posts

Redefining the Madwoman: Subverting Gender and Normalcy in Sandhya Mary’s Maria, Just Maria

Sandhya Mary’s Maria, Just Maria challenges the construct of normalcy by centering a seemingly mad woman as its unabashed protagonist.

Originally published in Malayalam in 2018, the novel was translated into English in 2024 by Jayasree Kalathil. Even in translation, Maria, Just Maria reads like the swirling, coiling letters of Malayalam due to its non-linear narrative structure, magical realist elements, and multiple “mad” characters. Yet, what distinguishes Mary’s novel is not its literary peculiarities, but the mere existence of a narrative voiced by a woman deemed mad by society.

Maria, Just Maria begins in a psychiatric hospital where, according to the doctors, Maria was admitted for exhibiting abnormal tendencies such as “giving up speaking.” But as is always the case, what men in power claim is only half the truth. Hence, while the narrative begins and ends in a psychiatrist’s hospital, the period in between is filled with Maria’s attempt at telling her own tale in her own way.

As Salman Rushdie observes in his famed novel Midnight’s Children (1981), you must swallow the whole world to understand just one life. In the same vein, Maria draws her imagined readers into her Kottarathil Veedu (her ancestral home) and compels them to witness the intricate lives of the four generations who lived and died before she was born with an inherited madness and a remarkably furious look on her face. Maria’s childhood is spent philosophizing with a talking dog and visiting toddy shops with her grandfather Geevarghese.

As she grows older, she resurrects dead ancestors to wander about in the astral plane and conjures up a Jesus Christ who learns from her colloquial Malayalam words such as dookly (loosely meaning “second-rate”). Maria, Just Maria does not follow the usual rising and falling action; instead, it is scattered with fragmented glimpses into the lives of the people who surround Maria as she gradually untangles her “mad” world. In the self-reflexive ending of the novel, she is back in her hospital room, pondering on the other possible ways she could end the book that she is planning to write (but has, in reality, already written), leaving the readers to wonder whether Maria is truly mad and if so, who determines the boundaries between sanity and madness?

Through a bleak, satirical tone and a deliberately disorganized narrative style, Maria, Just Maria calls for a deconstruction of the normal-abnormal binary, further situating it as the only way for the liberation of women.

What Is “Normal”?

The most radical lines in Maria, Just Maria come from a canine mouth. When Maria tries to educate her dog, Chandipatti, about color blindness in dogs, he repudiates, “Has any dog ever gone to a scientist and told them [that] it is color blindness?… Who are you humans to make these decisions for us?” Maria (and her dog) often makes the reader question their own grip on reality.

Throughout Maria, Just Maria, Mary presents a variety of characters—some labeled “mad” and some not—and ultimately reveals that they are fundamentally the same; they simply fall somewhere on the vast spectrum of being human. Maria’s friend, Vinayakan, who transitions from a great chess player to a “madman” on the street is no more or less normal than her lover, Aravind, who longs for Maria’s commitment despite her resistance.

While reflecting on the world’s relationship with madness, Maria argues that “real life is boring but madness might add a bit of interest to it” and quickly follows it with a realization that both are terribly boring. She declares that madness is not extreme; it is normal, unremarkable, and ultimately, boring.

Maria, Just Maria thus highlights that much like the notion of gender, the construct of normalcy and disability is social— and not, contrary to popular belief, totally biological. The instinct to attribute synonyms of lunacy to anyone whose actions fall outside one’s personal—and hence, limiting—comprehension exposes the arbitrary and subjective nature of such a classification.

It arises from an ableist and phallocentric authority that conveniently categorizes the marginals as “abnormal:” a woman who transgresses the male gaze, a man who exhibits femininity, or a trans person who simply exists. Society does not shy away from branding them as “crazy deviants.”

Similarly, what appears as madness for the other characters is, for Maria, simply her authentic nature unscathed by societal molding. As the author-translator conversation in Maria, Just Maria’s postscript also suggests, her madness is not a fixed pathological category but a fluid and relative label.

Rethinking Female Hysteria

Sandhya Mary’s madwoman stands in stark contrast to the quintessential madwoman of the literary canon who is presented as a beastly figure with disheveled hair and animalistic teeth lurking in the shadow of the moral, ideal, “normal” hero. From Ophelia in the river in Shakespeare’s Hamlet (1623) to Bertha Mason in the attic in Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre (1847), womanhood and hysteria have been linked like a sordid two-for-the-price-of-one deal.

While the binary of male rationality versus female insanity has been pervasive across both geographical and temporal distances, its origins can be traced down to the very etymology of the term. Hysteria originates from the Greek word for uterus, a faulty association undoubtedly made by those who did not possess the organ they claimed to know.

As a result, most narratives that employ the mad woman trope do so to evoke fascination, horror, and at times, pity in their readers, all of which are emotions that arise out of a supremacist attitude. In Maria, Just Maria, however, these emotions appear on the side of the madwoman—she is fascinated and horrified at the world’s reaction to nonconformity.

Since Maria is thrust outside the claustrophobic category of a “normal” woman, she acquires a place beyond the patriarchal rules that have always governed her kind. As a woman deemed “not quite right in the head,” she exercises a considerable degree of agency that allows her to voice radical ideas—on topics such as marriage and divorce, traditional gender roles, and limitations of educational systems—even if they oppose the rigid standards of society.

“Madness” as Agency

While Maria does not overtly exhibit feminist consciousness, the author uses the character to explore ideas that transcend global gender studies theories. When Maria’s “unwomanly” behavior—such as eating food off the floor, a desire to harm her bullying sister and her candid and offensive speech—land her in a psychiatrist’s office, what he prescribes for her is not counseling that can aid him in understanding her home environment better but a guidebook about a “well-behaved girl.”

Maria’s perceived insanity may have granted her a certain freedom to at best, reject conventional gender roles—or at worst, be perceived as selfish. Yet the very fact that such a rejection has to be classified as “insanity” is what remains most unsettling. As Elaine Showalter noted in The Female Malady (1987), insanity has historically been a penalty label for being a woman, or worse, for desiring or daring not to be.

By the end of Maria, Just Maria, it becomes evident that Maria ends up in the psychiatric hospital because she is authentic, rebellious, distinct, and most importantly, a woman unpoliced by society. From the witches of Salem to the feisty activists of today, history has made one thing clear: a woman left to her own devices is dangerous and hence must be promptly crushed.

Thus, with a flexible narrative and an uncompromising candid narrator, Maria, Just Maria links madness with agency; the mad woman ceases to be the “suppressed Other” and rises as a feminist figure. However, as Maria languishes in a psychiatric hospital, all alone with only her “mad thoughts” to keep her company, it becomes apparent that her agency and voice have come at the cost of social alienation. She is isolated, and at one point yearns to talk to someone, but finds none of her people around.

The madwoman’s attic is ultimately inescapable, her agency is turned into a pseudo-agency; after all, what freedom can one have locked up in a hospital ward? Pertinent questions such as these pervade the text: why must Maria’s unabashed selfhood be branded as madness? Is madness the only way out for a woman from patriarchy’s clutches? And if so, is such a freedom worth the fight?

While it picks apart social conventions surrounding gender, disability, and normalcy, Maria, Just Maria ultimately suggests that a woman can find true freedom perhaps only in a mad, mad world.

SUPPORT US

We like bringing the stories that don’t get told to you. For that, we need your support. However small, we would appreciate it.