How an unsophisticated malware attack became India’s biggest state-sponsored cybercrime

This is the third report in a three-part investigative series on the Elgar Parishad/Bhima Koregaon case. Read part one here and part two here.

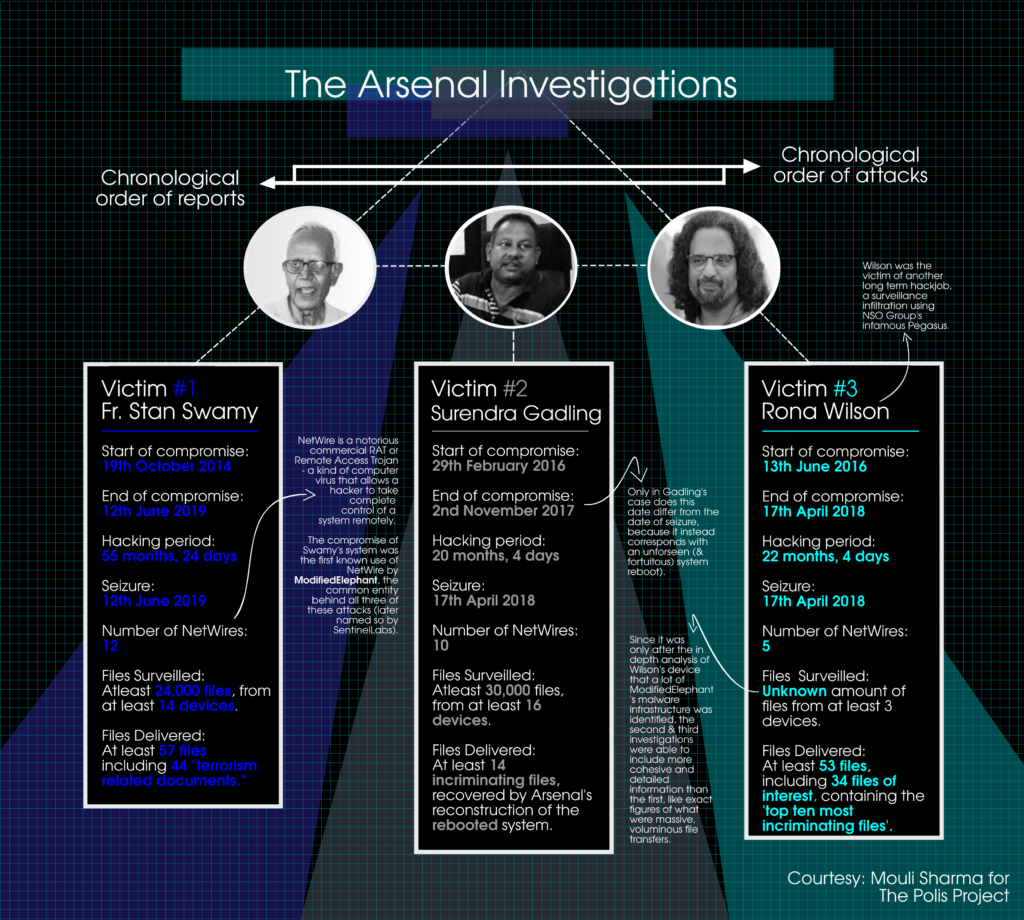

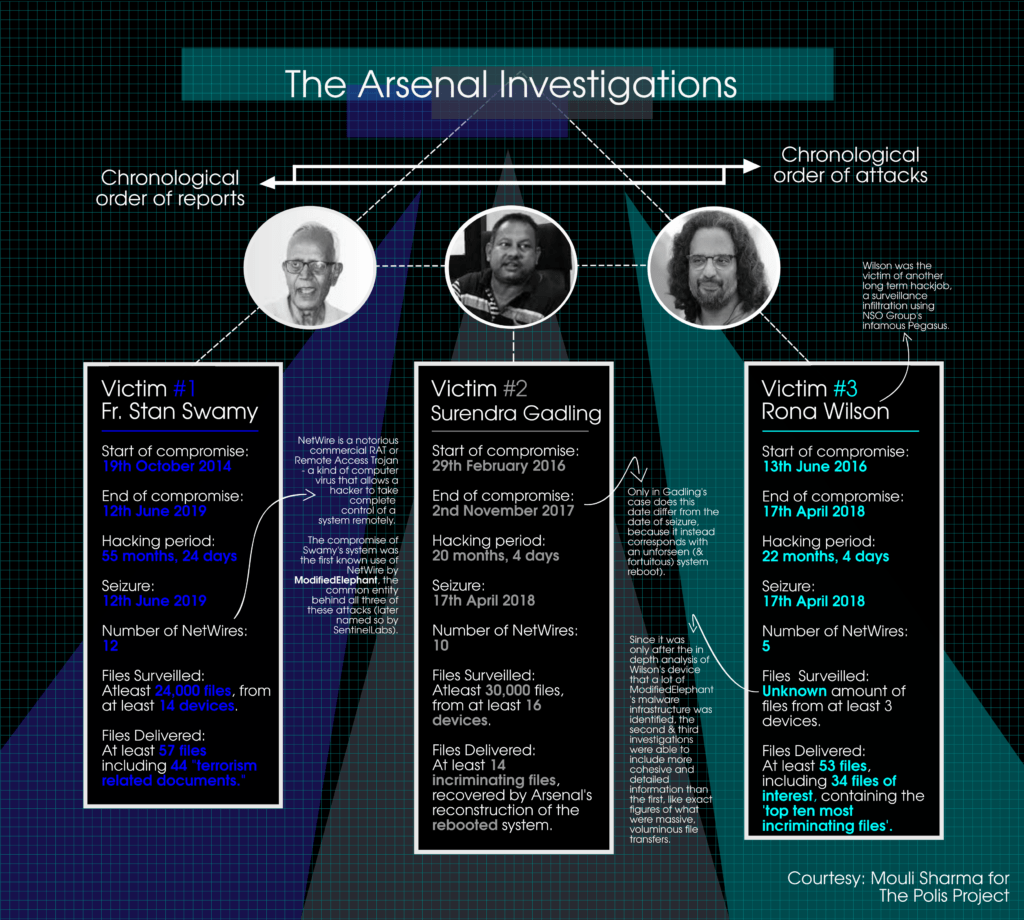

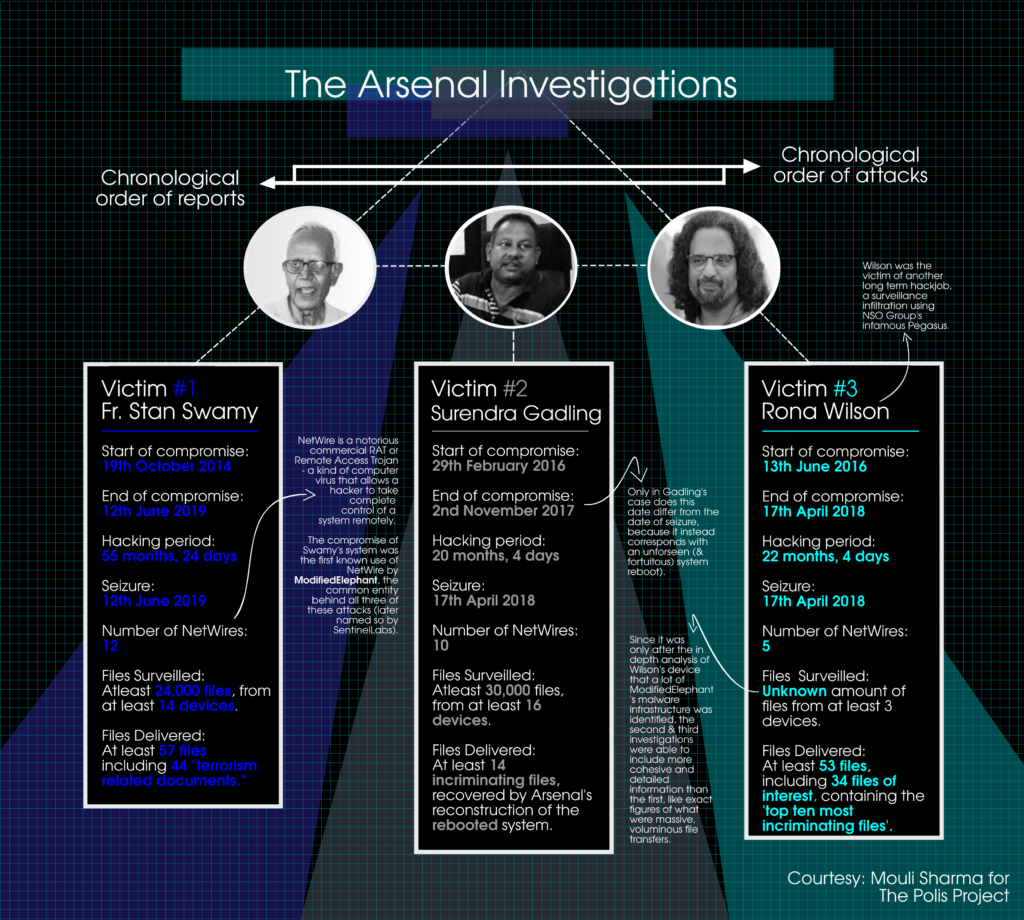

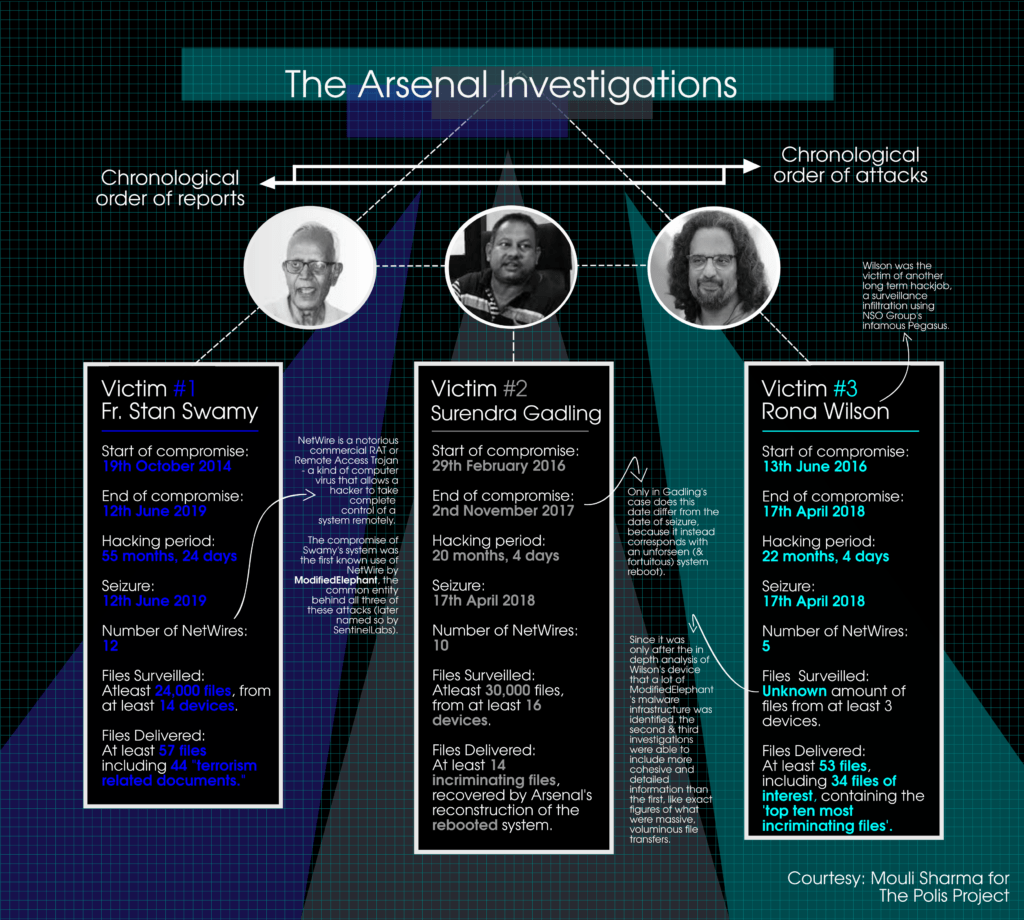

In October 2014, five months after the arrest of the professor GN Saibaba, Stan Swamy’s computer was hacked. Unbeknown to the world, the nascent stages of investigation against the prime accused in the Elgar Parishad case, who came to be monikered the BK-16, had already begun in 2014—four years before any of the arrests even took place.

The unknown attacker used a Remote Access Trojan—or RAT—sent through targeted phishing emails to compromise Swamy’s computer. A Trojan is a type of malware that downloads onto a computer disguised as a legitimate programme. The virus found in Swamy’s computer, then a recent but exciting entry into the world of commercial malware, would go on to become one of the most notorious Trojans of the 21st century: NetWire. At that time, both the attacker and their chosen malware were threat elements on the lower tiers of the cybercrime trade in terms of both technical proficiency and threat, years from falling on the radar of either international governments or independent investigators. But this would soon change drastically.

The 2014 compromise of Stan Swamy’s computer was only the start of a series of NetWire infiltrations targeting Indian human-right defenders (HRDs) that eventually snowballed into the massive cyber-conspiracy that forms the foundation of the Elgar Parishad/Bhima Koregaon case. The malware was in turn used to implant nearly a hundred incriminating files into the systems of the defendants—and that figure refers to the forensic investigations of the cloned devices of just three of the BK16—Swamy, Rona Wilson and Surendra Gadling.

After seizing their electronic devices, the Pune Police claimed to have found incriminating evidence on the computers of the defendants, which forms the main, formidable basis of the entire gamut of charges against the BK-16. But when it came to complying with the procedural mandate to supply all alleged incriminating material to the accused—as stipulated under Section 207 of the Code of Criminal Procedure to ensure a semblance of fairness before trials begin—the defendants encountered the prosecution’s persistent resistance. This dragging of feet itself has been suggestive of a guilty mind in respect of the probable mala fide contents. The defendants’ angst in this regard, at the very cusp of the trial, needs to be accounted for.

Tortuous legal battles had to be waged for the minimal fairness expected in the wake of the defendants’ shocking criminalisation. Even so, the police began submitting clone copies of these devices to the defendants rather tardily.

This was the context in which the legal defence teams managed to send the cloned copies onward for independent forensic examination, as they received them through the designated court—one by one. Wilson’s and Gadling’s trickled in first, followed by Swamy’s. A similar process is presumed to be still ongoing with the prosecution-provided clone copies of the electronic devices attributed to Hany Babu and others.

It is pertinent to note, as detailed in the second part of this series, that the Pune Police, which seized the electronic devices, did not record the hash values of the computers and removable devices at the relevant time. Neither at the time of seizure, nor before the state forensic labs transferred the digital data to other devices. As a result, the possibility of post-seizure manipulation of evidence, before providing the cloned copies, cannot be ruled out. However, the independent forensic analysis of the respective cloned copies further revealed a long campaign of malware attacks, cyber surveillance, and worst still, the fabrication of evidence—one that began years before the arrests, and continued right until days before the devices were seized.

Meanwhile, despite numerous perfunctory requests from Shivaji Pawar, the Pune Police’s investigating officer in the case until it was handed over to the National Investigation Agency (NIA), the state cyber forensic examiners at Pune and Mumbai had not offered a single reply to the most crucial query over the devices: had they shown any signs of tampering? The federal agency could by no means be unmindful of this, but it has, at the time of writing this report, not reported to have initiated any cognisable remedy in this regard.

There are sound reasons to believe that Maharashtra’s state forensic labs simply lack the wherewithal to provide a definitive answer—but multiple highly reputed international labs have conclusively determined significant evidence that demonstrates that all allegedly incriminating evidence was planted. The labs in question are known to have been approached, in the past, not only by private entities, but even by governments from the global north for many sensitive, important investigations, and there seems to be no room for doubt about their credibility. This report—the third and last part of the investigative series on the case—focuses on the forensic analyses by these international labs that are currently available in the public domain.

At the time of writing, the scope of the mass cyberattacks, which successfully compromised the systems of at least seven HRDs to conduct long term surveillance and incrimination, and spanned over a decade, has been substantially—if not completely—understood. Between five independent organisations and over ten cyber forensic reports, the targeted malware campaign against Indian HRDs has slowly unravelled, and the common attacker at its centre has taken a demystified shape, form, and even a name: the elusive ModifiedElephant. But this unravelling only began with the latter of two forensic reports by The Caravan. The first, published in December 2019 highlighted signs of evidence manipulation and fabrication in Surendra Gadling’s computer. In March 2020, the second report revealed that Rona Wilson’s system contained a Trojan horse. The report was published well over a year and a half after the Pune Forensic Laboratory had gone through the system and reported nothing anomalous.

The Caravan’s revelation triggered a series of independent investigations over the next few years—some voluntarily undertaken by international organisations who gained interest in the case as it garnered global scrutiny, some veritably sought by the defendants’ legal teams. In 2022, an independent report by cybersecurity firm SentinelOne titled, “ModifiedElephentAPT: Ten Years of Fabricating Evidence,” first christened the eponymous attacker and revealed that they had been active since at least 2012—the same year NetWire began to be sold!

Hidden within the lines of code and forensics in ten reports reviewed by The Polis Project—seven device-specific forensic examinations and three trying to unearth branches of ModifiedElephant—we found large and small revelations about the precise intentions of the malware infrastructure in targeting the people it did, and exactly when and how it came to line up with the Pune Police’s investigation of the BK-16. Perhaps most important of these is Shivaji Pawar: the investigating officer of the Elgar Parishad case for two years, who carried out the first ten arrests in the case and filed two chargesheets. In the cases of the above three defendants, at least, Pawar had direct links with the malware infrastructure and fabrication of evidence.

But understanding these revelations requires us to first understand ModifiedElephant itself, the cyberspace-time that it was operating in, and the fascinating timeline of its evolution over the course of an entire decade.

Phase One: Origin—The Beginnings of NetWire & ModifiedElephant

The answer to exactly what is this curious creature named “ModifiedElephant,” it is perhaps better to ask, “Who exactly is (or are) ModifiedElephant?” ModifiedElephant (ME), is what is known in the world of cybersecurity as an Advanced Persistent Threat (APT): a targeted attack campaign in which an intruder, or team of intruders, establishes an illicit, long-term presence among a network or group of people in order to mine highly sensitive data. It is the kind of hacking nexus that ordinary people expect to be a myth only discussed by digital security experts and fiction writers; the kind that takes down countries.

The first signs of ME’s activity in the Indian subcontinent, as discovered by SentinelOne a whole decade later, could be traced back to as early as 2012. Back then, ME had just begun to operate within the Indian subcontinent as a relatively unadvanced threat targeting human rights lawyers, tribal rights activists, and government critical academics—the exact profile usually hidden behind the government’s vicious use of terms like “urban Naxal”–starting with the Gadchiroli arrests that began just a year later. During this time, SentinelOne reported, ME made use of primitive keylogging techniques to spy on the everyday computer use of their victims. Keylogging refers to a surveillance technique that records every keystroke by a computer user, say using a virus, through which the attacker can gain access to passwords and private information. SentinelOne describes these early techniques in its report on ME’s evolution with much derision, highlighting that the code was unsophisticated and inefficient, often stolen from online hacking forums.

[The keyloggers], packed at delivery, are written in Visual Basic and are not the least bit technically impressive. Moreover, they’re built in such a brittle fashion that they no longer function. The overall structure of the keylogger is fairly similar to code openly shared on Italian hacking forums in 2012. In some ways, [ME’s code] is far more brittle than the code [on the forums] as it relies on specific web content to function.

In the same year, an innocuous sounding domain, named “worldwidewebs[.]com” was registered online, introducing to the cybercrime market a new and upcoming RAT: the infamous NetWire. This early version of NetWire had not yet fully realised the true extent of the remote access capacities that it would come to be identified by. Ironically, the primary feature that this version could reliably perform was but keylogging. In the next two years, NetWire would grow into a malware with an enviable tenacity for remote access. It is during these years that ModifiedElephant would come to choose NetWire as the primary tool of their malware infrastructure, beginning with the infiltration of Stan Swamy’s system in 2014.

Phase Two: Infection—The Slow Spread of ModifiedElephant’s Hacking Nexus

ME’s primary means of distributing their malware, be it their initial keylogging codes or eventual NetWire executables, was through mass-forwarded phishing emails sent through spam accounts of service providers like Google, Yahoo, etc. Since these service providers do not charge for accounts, and more importantly, do not require identity verification in many parts of the world, creating as many untraceable accounts as required has been convenient for hackers like ME. After the compromise of Stan Swamy’s email—likely the first, and by far the most successful, attack—ME’s targeting of the Elgar Parishad accused and their closest associates became even more explicit.

ME used Swamy’s email to cast a snowball net specifically targeting his friends and confidants within the left-intellectual sphere, ensuring that future victims received the infected emails from those they trusted. By early 2016, the emails of Harshal Lingayat, Arun Ferreira, and Prashant Rahi were brought into the mesh of compromised identities. It was through these emails that the second computer hard disk surrendered by the prosecution for forensic cross-verification was compromised: that of Surendra Gadling in February 2016.

The compromise of Gadling’s system was also chronologically the second of the three attacks so far investigated and reported, shortly followed by that of Rona Wilson, in June 2016. The nature and timeline of these three attacks relative to each other, which we shall call the Arsenal-investigated attacks based on the agency that uncovered them in depth, are particularly essential to understanding the workings and modus operandi of ME. (A detailed reference of all the incriminating documents and forensic reports is available here.)

Like with Gadling, the method of delivery of the virus to Wilson’s system also involved the hackers posing as a trusted confidant, this time co-accused Varavara Rao. Hany Babu’s email was also hacked at an unconfirmed point in the chain of events.

Phase Three: Occupation—I Spy With My Little Eye

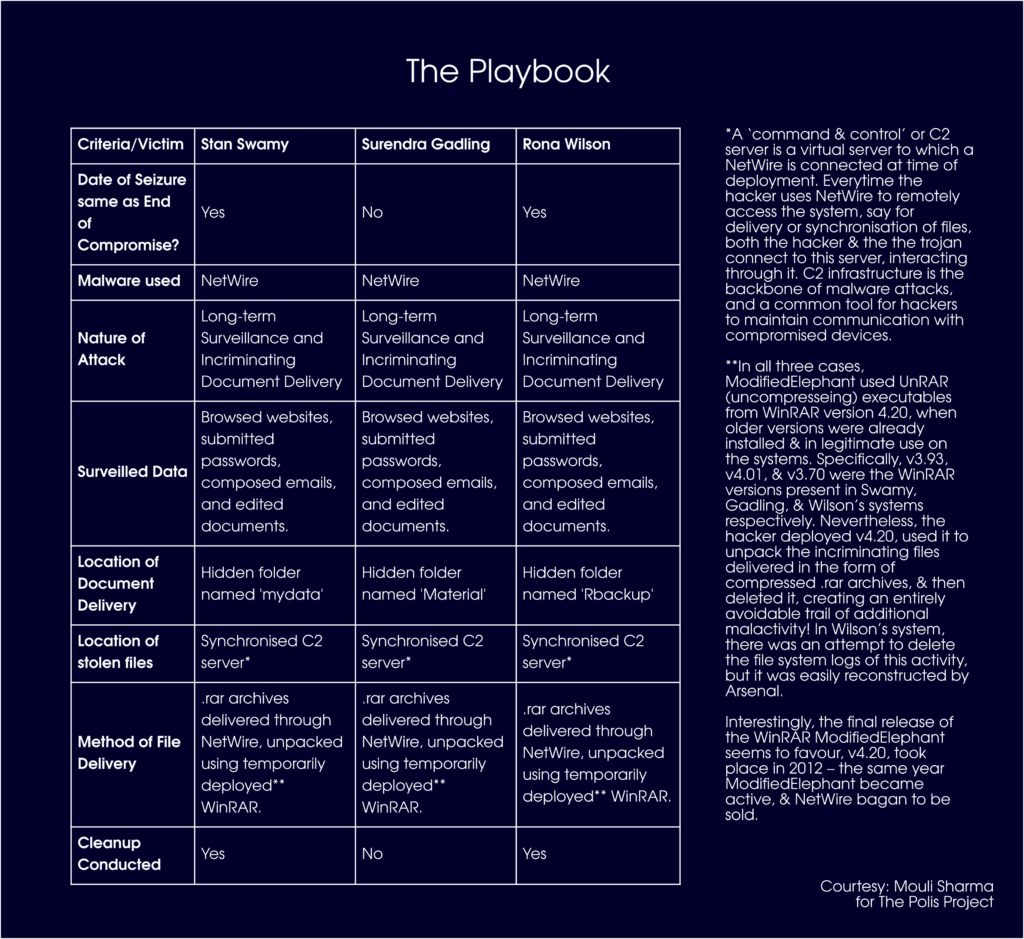

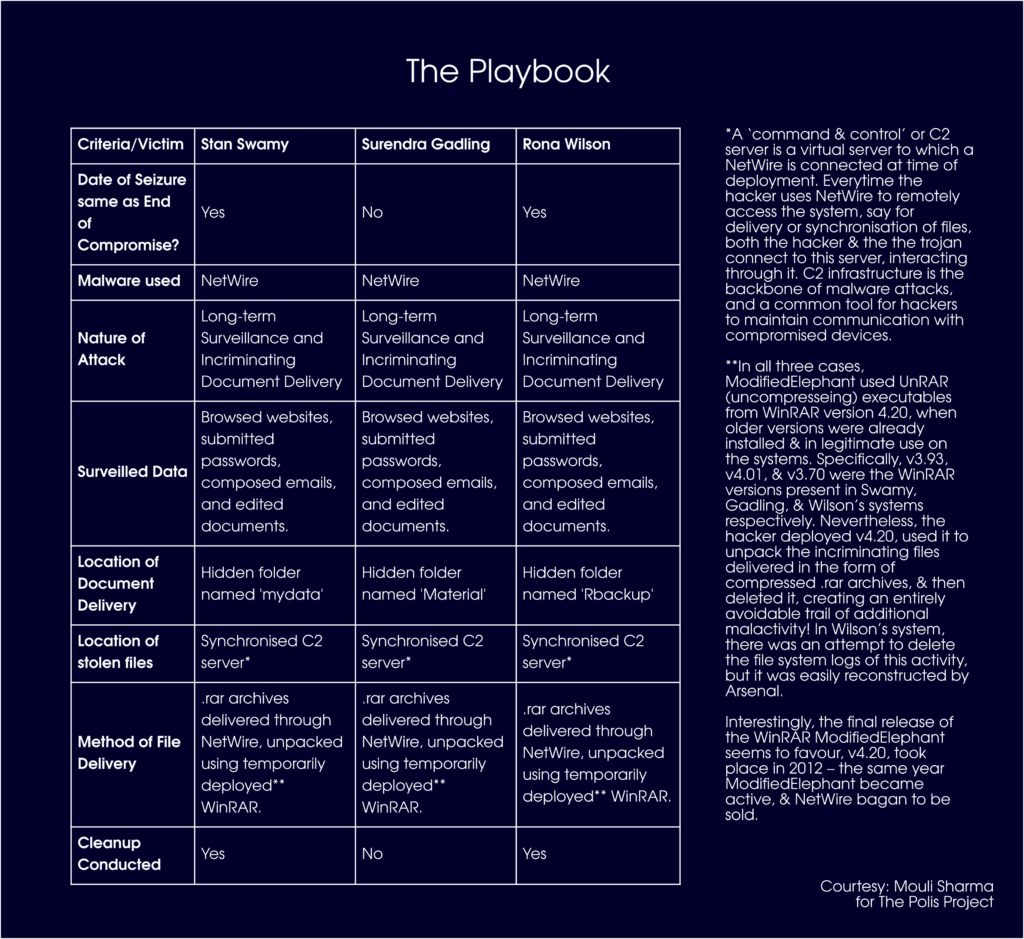

After the successful infiltrations of the systems of Swamy, Gadling, and Wilson—in that order—began a long refrain of intense and shocking surveillance. Entire drives were mirrored and synchronised with the hackers’ virtual servers. Everything from typed documents, shared and received emails, and browsed websites to sensitive data like passwords and account logins was logged and monitored, for months on end. Mark Spencer, the president of Arsenal Consulting, examined all three accused persons’ devices and published five detailed reports on them between 2021 and 2022, after the first was sought by Rona Wilson’s defence team. In the reports, Spencer writes, “It should be noted that this is one of the most serious cases involving evidence tampering that Arsenal has ever encountered, based on various metrics which include the vast timespan between the delivery of the first and last incriminating documents on multiple defendants’ computers.”

In her book, The Incarcerations: Bhima Koregaon and the Search for Democracy in India, Alpa Shah writes that Spencer was initially very sceptical of the possibility of malicious activity. He found it absurd that such a blatant operation could go undiscovered in even the most elementary forensic analyses, especially in a case as high profile as this one. “I expected we would quickly rule in or out whether there was suspicious activity on Rona Wilson’s computer,” Spencer told Shah. “I was leaning towards ruling out. What I did not expect in any way was to be walking into a massive cesspool of attack infrastructure, aggressive surveillance, and electronic evidence tampering.”

By far the most extensive of the three attacks was the one detected against Stan Swamy. It comprised not one but three separate NetWire campaigns spread across 12 distinct virus samples, over the course of a colossal 52-month duration. The infiltration of his computer led to the illicit transfers of the contents of 13 removable storage devices containing over 24,000 files, followed by a failed clean-up, with a trail leading all the way up to the eve of seizure of his devices by the Pune Police in June 2019.

In comparison, the attack on Gadling’s computer was shorter—prematurely cut off in November 2017, after 20 months of infiltration, due to a fortuitous decision to reinstall the computer’s operating system. It spared him another five months of being hacked, but the delivery of plentiful incriminating documents to his computer had already taken place. The attack on Rona Wilson’s system lasted 22 months, right till one week before the seizure of his devices on 17 April 2018.

While ME conducted these long-term surveillance operations via NetWire, another nefarious malware was making its way through the circuit of its chosen victims—predominantly human-rights activists, lawyers, and left-leaning intellectuals. Only this one was neither commercially available nor operated by low-skilled professional hacker networks. The infamous spyware Pegasus, of Israel’s NSO group, sold exclusively to governments and their militaries as the subject of much ethical controversy, was successfully inserted into Rona Wilson’s presumed iPhone in July 2017. This was around the same time when the deliveries of incriminating documents to all three systems had begun. Another curious link between the Pegasus and ME attacks was that just like the latter, the Pegasus infection also stopped in April 2018, just before the first round of Pune Police seizures.

In August 2021, Arsenal confirmed the Pegasus infection, casting unshakeable doubt on a governmental role in the cyber conspiracy. A year later, the Supreme Court also stated that at least five out of 29 allegedly compromised phones were infected with some malware, but the then chief justice NV Ramana noted that the central government did not cooperate with the technical investigation, and as such the use of Pegasus could not be confirmed, putting the lid on the matter.

Phase Four: Delivery—Fabrication and Plantation of Incriminating Evidence

On 3 November 2016, ME used the remote access feature of NetWire for the first time for the creation of a file on a compromised system, as opposed to extraction or observation that had been conducted till then. The attacker created a hidden folder called “Rbackup” on Rona Wilson’s computer. Wilson’s defence team had provided Arsenal with a list of the “top ten” incriminating documents that the Pune Police relied upon to build a case against him, as well as “24 additional files of interest.” The forensic analysis revealed that it is into this “Rbackup” folder that the attacker illicitly planted all 34 documents—the top ten incriminating files as well as the 24 additional ones— over the course of a year between March 2017 and 2018.

Similar hidden folders were created on the systems of Stan Swamy and Surendra Gadling as well, with the timings of all three operations overlapping significantly. In all three cases, Arsenal found that the users of the computers—Wilson, Gadling and Swamy—had never interacted with the incriminating files, or the hidden folders containing them, at all.

ME’s process for the delivery of files was elementary and extremely traceable, enough that Arsenal was able to recreate their entire history of illicit activity from the clone files alone, of which Gadling’s had been rebooted completely down to the operating system:

- First, ME would create a folder nested deep within other infrequently used folders on the system (determined easily after the intense monitoring activity) and set it to “hidden.”

- Second, ME would deliver “.rar” archives, which are compressed folders, containing documents either related to the banned CPI (Maoist) or downright fabricated to indicate authorship of the accused, into the hidden folders.

- Third, ME would temporarily deploy a version of WinRAR (a tool to unpack compressed files), unpack the .rar archives, and then delete both the archives and the temporarily deployed version of WinRAR.

This fairly convoluted process served as ME’s modus operandi for the delivery of incriminating files with all three attacked systems, and consequently left behind an avalanche of evidence of illicit activity due to its unsophisticated nature. Using logs left behind by the use of the virus, the Windows file system, as well as the all-too-traceable history of WinRAR use, Arsenal was able to retrace nearly every step of the attacker’s digital activity down to the millisecond when they were performed. In addition, ME also made many grave errors, including a desperate clean-up effort (elaborated in a later section) that was cut short due to an unsuitably timed shutdown of Swamy’s system.

Another error was a botched file delivery between Wilson and Gadling’s systems. On 22 July 2017, ME used the trojans in Gadling’s and Wilson’s respective systems—both compromised at this time—to remotely access them simultaneously for the purpose of delivering incriminating documents. Likely in confusion, ME accidentally delivered a file named “CC –Financial Policy.docx” to Wilson’s system, though it was in fact intended to be delivered to Gadling’s computer, where it would be eventually discovered. Noticing their error, ME quickly delivered the file to Gadling’s system and deleted it from Wilson’s, the whole process taking about twenty minutes.

Despite small—but significant—errors like this one, ME’s access either to legitimate documents related to the banned CPI (Maoist), or to sufficient knowledge about them to fabricate details themselves, or to both, indicate the involvement of a powerful and resourceful entity. As Spencer stressed repeatedly in each of Arsenal’s five reports, “the attacker had extensive resources (including time).” After Arsenal’s involvement, the modus operandi of evidence fabrication, incriminating document delivery as well as the apparent high-profile nature of the attack drew the attention of an independent, California-based threat security intelligence firm, SentinelOne and their forensic body SentinelLabs.

In September 2021, a report by Juan Andres Guerrero-Saade and Igor Tsemakhovich for SentinelLabs covered in great detail the operations of a Turkey-based APT whom they named EGoManiac, due to the repeated use of the initials EGM in their malware infrastructure. Like in the case of ModifedElephant, EGoManiac’s attacks involved the infiltration of victim systems—in this case a group of Turkish journalists—using RATs to implant incriminating documents that were then used to justify arrests by the Turkish National Police and wrongfully incarcerate the victims for several years.

In both cases, Arsenal Consulting played a key role as an independent agency that revealed the true cyber-forensic extent of the attacks when the state agencies did not. In fact, following Sentinel’s report on EGoManiac, Arsenal Consulting alerted them to the targeted attacks on HRDs in India. Guerrero-Saade, alongside another Sentinel threat researcher Tom Hegel, conducted an extensive cyber forensic examination of the nature of digital espionage in India, ultimately identifying a common attacker they named the ModifiedElephant APT.

ModifiedElephant’s case in isolation may seem sensational and absurd, but is nowhere near as reviling as the reality that is the emergent sector of state-sponsored cyberespionage and conspiracy, casting doubt on the very premise of electronic devices being brought into courts as evidence in cases involving national security.

“A threat actor willing to frame and incarcerate vulnerable opponents is a critically underreported dimension of the cyber threat landscape that brings up uncomfortable questions about the integrity of devices introduced as evidence,” says the Sentinel report. “[ModifiedElephant] has operated for years, evading research attention and detection due to their limited scope of operations, the mundane nature of their tools, and their regionally-specific targeting.”

Phase Five: Seizures—A Desperate Clean-up Attempt

With the exception of the attack against Gadling—cut short when he had Windows reinstalled on his system, ostensibly by a professional for unrelated technical troubles—the two other ME attacks on Wilson and Swamy ended with suspicious last-minute activity on the victims’ devices. In Wilson’s case, this constituted a close monitoring of file system logs well into the night of 16 April—the eve of the seizure—as well as a retreat of Pegasus from his iPhone six days earlier.

In Swamy’s case, to say that the last-minute activity was suspicious would be an understatement. On 11 June 2019, a day before the seizure of his devices, ME began to perform an extensive clean-up of their malicious activities using NetWire, including crude anti-forensic activity, which was abruptly interrupted by the user—presumably Swamy—unknowingly shutting down the computer at 9 pm, right before the virus could be set up for a so-called self-destruction. The clean-up involved, broadly, the deletion of traces of surveillance and incrimination activity; the creation of “noise” to obfuscate illicit activity; and renaming malicious folders to unsuspicious names such as “Desktop” and “Opera.”

The deletion of the traces of surveillance activity included one massive deletion of 14,313 files from a hidden staging area used for siphoning files to the hackers’ servers, using a command for “forceful and quiet” deletion. Similarly desperate commands were used for the creation of “noise” in two folders where malicious activity had taken place, ignoring errors and suppressing file safety prompts. Ironically, the desperate deletions of files and activity logs did not prevent Arsenal from reconstructing the logs of the deletions themselves; another crucial failure in ME’s efforts.

It should be reiterated here that ME’s attack on Swamy’s computer was far more extensive than that on either Wilson or Gadling; it lasted more than a year past the activity on Wilson’s system and nearly two years more than that on Gadling’s. Both the number of NetWires deployed to Swamy’s system and their versions were more advanced than those used in either of the other attacks, therefore it is not extraordinary for ME’s campaign against Swamy to possess some unique characteristics. However, it is nonetheless noteworthy that such a desperate, and intense attempt at clean-up would be made in his system specifically, when there was absolutely no effort towards erasing their tracks in the other two systems, where the evidence delivered was far more severe, like the infamous “Ltr_1804_to_CC.pdf” on Rona Wilson’s system that ideates a plot to assassinate the prime minister and a sensational plan to purchase arms and ammunition.

In this context, it is all the more relevant that the seizures of Stan Swamy’s devices took place over a year after the first wave of arrests, giving ample time for the grains of the prosecution’s sand-built case against Gadling and Wilson to crumble. After April 2018, Pune Police had quickly emptied its hand of digital evidence against the defendants, having planted the files recovered from Wilson’s system into the media, and in doing so attracted scrutiny from both the relevant superior courts and the global citizenry at large.

By mid 2019, before the police raided Swamy’s home, the defence teams of Wilson and Gadling had already begun to push for the provision of device clones for their analyses—a push the prosecution knew they could not continue blocking for too long. The threads of ME’s painstakingly built tapestry of digital fiction had already begun to unravel. So, in all likelihood, the clean-up on Swamy’s computer was a desperate, last-ditch effort at holding together the fabricated plot.

Who is ModifiedElephant? The Discovery of a Direct Link to the Pune Police

It is crucial to note that in all three cases, the deliveries of incriminating files had already begun months before the Bhima Koregaon violence took place. And yet, the delivery of files pertaining to Elgar Parishad or any alleged conspiracy around it did not begin until January 2018, after the registration of the FIR against Sambhaji Bhide and Milind Ekbote. By all indications, then, the attacker was already planting the seeds for their victims to be framed in some kind of ‘Maoist links’ case, same as was done to the six targeted in the Gadchiroli case. It was only after the Bhima Koregaon violence took place that the attacker began making efforts to implicate them in the same, as a convenient retrospective. But how and why did this shift of strategy take place?

Pulling on that thread unravels a slew of countless more incongruences nested within the unknown and elusive motivations of ModifiedElephant: why were the BK-16 and other human rights activists the target profile for ME’s attacks? Considering that the actor made no attempts whatsoever to use them for financial gain or fraud, despite having unrestricted access to the private information of their victims and their online identities, what was their incentive? A low-skilled or unsophisticated attack though it may have been, it is inarguable that the malware infrastructure run by ModifiedElephant for this campaign was a competent, technically qualified, and professional one, by cyber threat standards; so who employed them? Why didn’t they do a better job of establishing a digital trail of use of the incriminating documents, why didn’t they do a better job of hiding their own illicit activity? And last but certainly not least: how did they know to cease the figurative cyberfire just ahead of the infected systems being raided and seized, before the raids were finalised?

Each of these questions points toward a damning, if obvious, conclusion: ModifiedElephant had direct links to the state and law enforcement, and was operating either on their directions or in their favour whilst maintaining some form of communication with them in real time. Though the signs all indicated this, such as the state forensic labs’ obfuscation of the malware attacks and the curious parallels in the investigative procedures and the illicit activity, it was not until June 2022 that it went from an obvious speculation, to confirmed fact.

In an exclusive report by WIRED, four independent sources revealed a shocking forensic discovery. In their report for SentinelLabs, the researchers Guerrero-Saade and Hegel had stopped short of identifying the actor behind ME. But the WIRED report noted that the researchers had subsequently worked with a security analyst at a yet unnamed email provider and discovered that there was a recovery email and a recovery phone number added to the compromised emails of Wilson, Gadling and Babu. This would allow the attacker to regain control to the emails if the password was changed. “To the researchers’ surprise, that recovery email on all three accounts included the full name of a police official in Pune who was closely involved in the Bhima Koregaon 16 case,” the WIRED report noted.

WIRED then approached two other security researchers, who identified the recovery phone number as being associated with the same police official in multiple open-source police databases as well as a leaked TrueCaller database. The researchers also found that the WhatsApp photo for the recovery number was a selfie photo of the police official, which the report notes, was “a man who appears to be the same officer at police press conferences and even in one news photograph taken at the arrest of Varavara Rao.”

The WIRED report did not disclose the identity of the police official. But it is this crucial detail of the photograph with Varavara Rao that led the author Alpa Shah to identify the officer, which she then confirmed with the WIRED team as well.

The email and phone number belonged to none other than the investigating officer of the Elgar Parishad case for the Pune Police: Shivaji Pawar, himself.

The End of NetWire, A Lead (to) for the Future

In March 2023, the United States Federal Bureau of Investigation seized the domain named “worldwiredlabs[.]com.” Around the same time, a Croatian national was arrested for administering the website, and a computer server in Switzerland was seized for hosting much of its material infrastructure. This is the website on which NetWire had been sold for over a decade, since 2012.

In many ways, the evolution of NetWire and ModifiedElephant grew in parallel. They both started out in 2012, forming relatively low-threat parts of high-threat infrastructures, and grew into behemoths in the world of cyberespionage. The rise and evolution of NetWire concurrently supported and enabled the ambitious expansion of ModifiedElephant’s noxious campaigns against innocent activists and critical voices within India’s political sphere; its downfall is the best lead this country has toward uncovering what may be an even larger nexus of cyber-threats that endanger the fabric of India’s democracy.

With NetWire out of the picture, ModifiedElephant is likely to switch over to DarkComet, another commercial Trojan they occasionally and sparingly made use of in their campaigns. But with or without options, the walls are closing in; the myriad of indicators and fingerprints already picked up by Arsenal from the three defendants’ devices, and in all likelihood also Hany Babu’s, has been expanded into a barrage of indicting markers in the Sentinel report. Additionally, the Sentinel report also mentioned another APT called SideWinder, which has been acting alongside ModifiedElephant, targeting the same profile of victims, thus further expanding the suspected pool of state-sponsored threat actors.

A year after Pandu Narote died in custody of a treatable illness and seven months before Saibaba passed away from a complication from conditions exacerbated in prison, the Bombay High Court acquitted the Gadchiroli six. Coming full circle from the genesis of the BK-16 myth with the convictions of the Gadchiroli six in March 2017—the same time incriminating documents began to be planted into the systems of Wilson, Gadling and Stan Swamy—the judgment upon which the entire case mounted against the BK16 rested was overturned in March 2024 Over 10 years after they were arrested, following the remarkable final hearing of Mahesh Kariman Tirki and others, the six accused of having “Maoist links” were deemed innocent on all counts and released due to invalid prosecution sanctions, stock witnesses, and a complete absence of credible evidence. The electronic evidence against them was dismissed due to egregious procedural violations, casting a reasonable doubt over the possible tampering.

The foundations of the Elgar Parishad/Bhima Koregaon conspiracy case are, therefore, deemed to crumble under the weight of time and global scrutiny. Slowly but surely, the truth behind the impressive, monstrous amounts of lies concocted from sheer, commendable imagination has been coming out into the public domain. If the case still stands today, with six of the BK16 still behind bars, it could only mean that our superior courts have yet to abandon their leniency towards the law-enforcing wing of the state. As Mahesh Kariman Tirki and others presupposes, it is possible for justice to be drawn closer than could be imagined with a distant and protracted trial, if only their Lordships would care to seriously consider a thorough appraisal of the case as a whole, hopefully through a suo motu quashing petition. All that’s left to do then, is wait for judgement day to come.

This is the third report in a three-part investigative series on the Elgar Parishad/Bhima Koregaon case. Read part one here and part two here.

Related Posts

How an unsophisticated malware attack became India’s biggest state-sponsored cybercrime

In October 2014, five months after the arrest of the professor GN Saibaba, Stan Swamy’s computer was hacked. Unbeknown to the world, the nascent stages of investigation against the prime accused in the Elgar Parishad case, who came to be monikered the BK-16, had already begun in 2014—four years before any of the arrests even took place.

The unknown attacker used a Remote Access Trojan—or RAT—sent through targeted phishing emails to compromise Swamy’s computer. A Trojan is a type of malware that downloads onto a computer disguised as a legitimate programme. The virus found in Swamy’s computer, then a recent but exciting entry into the world of commercial malware, would go on to become one of the most notorious Trojans of the 21st century: NetWire. At that time, both the attacker and their chosen malware were threat elements on the lower tiers of the cybercrime trade in terms of both technical proficiency and threat, years from falling on the radar of either international governments or independent investigators. But this would soon change drastically.

The 2014 compromise of Stan Swamy’s computer was only the start of a series of NetWire infiltrations targeting Indian human-right defenders (HRDs) that eventually snowballed into the massive cyber-conspiracy that forms the foundation of the Elgar Parishad/Bhima Koregaon case. The malware was in turn used to implant nearly a hundred incriminating files into the systems of the defendants—and that figure refers to the forensic investigations of the cloned devices of just three of the BK16—Swamy, Rona Wilson and Surendra Gadling.

After seizing their electronic devices, the Pune Police claimed to have found incriminating evidence on the computers of the defendants, which forms the main, formidable basis of the entire gamut of charges against the BK-16. But when it came to complying with the procedural mandate to supply all alleged incriminating material to the accused—as stipulated under Section 207 of the Code of Criminal Procedure to ensure a semblance of fairness before trials begin—the defendants encountered the prosecution’s persistent resistance. This dragging of feet itself has been suggestive of a guilty mind in respect of the probable mala fide contents. The defendants’ angst in this regard, at the very cusp of the trial, needs to be accounted for.

Tortuous legal battles had to be waged for the minimal fairness expected in the wake of the defendants’ shocking criminalisation. Even so, the police began submitting clone copies of these devices to the defendants rather tardily.

This was the context in which the legal defence teams managed to send the cloned copies onward for independent forensic examination, as they received them through the designated court—one by one. Wilson’s and Gadling’s trickled in first, followed by Swamy’s. A similar process is presumed to be still ongoing with the prosecution-provided clone copies of the electronic devices attributed to Hany Babu and others.

It is pertinent to note, as detailed in the second part of this series, that the Pune Police, which seized the electronic devices, did not record the hash values of the computers and removable devices at the relevant time. Neither at the time of seizure, nor before the state forensic labs transferred the digital data to other devices. As a result, the possibility of post-seizure manipulation of evidence, before providing the cloned copies, cannot be ruled out. However, the independent forensic analysis of the respective cloned copies further revealed a long campaign of malware attacks, cyber surveillance, and worst still, the fabrication of evidence—one that began years before the arrests, and continued right until days before the devices were seized.

Meanwhile, despite numerous perfunctory requests from Shivaji Pawar, the Pune Police’s investigating officer in the case until it was handed over to the National Investigation Agency (NIA), the state cyber forensic examiners at Pune and Mumbai had not offered a single reply to the most crucial query over the devices: had they shown any signs of tampering? The federal agency could by no means be unmindful of this, but it has, at the time of writing this report, not reported to have initiated any cognisable remedy in this regard.

There are sound reasons to believe that Maharashtra’s state forensic labs simply lack the wherewithal to provide a definitive answer—but multiple highly reputed international labs have conclusively determined significant evidence that demonstrates that all allegedly incriminating evidence was planted. The labs in question are known to have been approached, in the past, not only by private entities, but even by governments from the global north for many sensitive, important investigations, and there seems to be no room for doubt about their credibility. This report—the third and last part of the investigative series on the case—focuses on the forensic analyses by these international labs that are currently available in the public domain.

At the time of writing, the scope of the mass cyberattacks, which successfully compromised the systems of at least seven HRDs to conduct long term surveillance and incrimination, and spanned over a decade, has been substantially—if not completely—understood. Between five independent organisations and over ten cyber forensic reports, the targeted malware campaign against Indian HRDs has slowly unravelled, and the common attacker at its centre has taken a demystified shape, form, and even a name: the elusive ModifiedElephant. But this unravelling only began with the latter of two forensic reports by The Caravan. The first, published in December 2019 highlighted signs of evidence manipulation and fabrication in Surendra Gadling’s computer. In March 2020, the second report revealed that Rona Wilson’s system contained a Trojan horse. The report was published well over a year and a half after the Pune Forensic Laboratory had gone through the system and reported nothing anomalous.

The Caravan’s revelation triggered a series of independent investigations over the next few years—some voluntarily undertaken by international organisations who gained interest in the case as it garnered global scrutiny, some veritably sought by the defendants’ legal teams. In 2022, an independent report by cybersecurity firm SentinelOne titled, “ModifiedElephentAPT: Ten Years of Fabricating Evidence,” first christened the eponymous attacker and revealed that they had been active since at least 2012—the same year NetWire began to be sold!

Hidden within the lines of code and forensics in ten reports reviewed by The Polis Project—seven device-specific forensic examinations and three trying to unearth branches of ModifiedElephant—we found large and small revelations about the precise intentions of the malware infrastructure in targeting the people it did, and exactly when and how it came to line up with the Pune Police’s investigation of the BK-16. Perhaps most important of these is Shivaji Pawar: the investigating officer of the Elgar Parishad case for two years, who carried out the first ten arrests in the case and filed two chargesheets. In the cases of the above three defendants, at least, Pawar had direct links with the malware infrastructure and fabrication of evidence.

But understanding these revelations requires us to first understand ModifiedElephant itself, the cyberspace-time that it was operating in, and the fascinating timeline of its evolution over the course of an entire decade.

Phase One: Origin—The Beginnings of NetWire & ModifiedElephant

The answer to exactly what is this curious creature named “ModifiedElephant,” it is perhaps better to ask, “Who exactly is (or are) ModifiedElephant?” ModifiedElephant (ME), is what is known in the world of cybersecurity as an Advanced Persistent Threat (APT): a targeted attack campaign in which an intruder, or team of intruders, establishes an illicit, long-term presence among a network or group of people in order to mine highly sensitive data. It is the kind of hacking nexus that ordinary people expect to be a myth only discussed by digital security experts and fiction writers; the kind that takes down countries.

The first signs of ME’s activity in the Indian subcontinent, as discovered by SentinelOne a whole decade later, could be traced back to as early as 2012. Back then, ME had just begun to operate within the Indian subcontinent as a relatively unadvanced threat targeting human rights lawyers, tribal rights activists, and government critical academics—the exact profile usually hidden behind the government’s vicious use of terms like “urban Naxal”–starting with the Gadchiroli arrests that began just a year later. During this time, SentinelOne reported, ME made use of primitive keylogging techniques to spy on the everyday computer use of their victims. Keylogging refers to a surveillance technique that records every keystroke by a computer user, say using a virus, through which the attacker can gain access to passwords and private information. SentinelOne describes these early techniques in its report on ME’s evolution with much derision, highlighting that the code was unsophisticated and inefficient, often stolen from online hacking forums.

[The keyloggers], packed at delivery, are written in Visual Basic and are not the least bit technically impressive. Moreover, they’re built in such a brittle fashion that they no longer function. The overall structure of the keylogger is fairly similar to code openly shared on Italian hacking forums in 2012. In some ways, [ME’s code] is far more brittle than the code [on the forums] as it relies on specific web content to function.

In the same year, an innocuous sounding domain, named “worldwidewebs[.]com” was registered online, introducing to the cybercrime market a new and upcoming RAT: the infamous NetWire. This early version of NetWire had not yet fully realised the true extent of the remote access capacities that it would come to be identified by. Ironically, the primary feature that this version could reliably perform was but keylogging. In the next two years, NetWire would grow into a malware with an enviable tenacity for remote access. It is during these years that ModifiedElephant would come to choose NetWire as the primary tool of their malware infrastructure, beginning with the infiltration of Stan Swamy’s system in 2014.

Phase Two: Infection—The Slow Spread of ModifiedElephant’s Hacking Nexus

ME’s primary means of distributing their malware, be it their initial keylogging codes or eventual NetWire executables, was through mass-forwarded phishing emails sent through spam accounts of service providers like Google, Yahoo, etc. Since these service providers do not charge for accounts, and more importantly, do not require identity verification in many parts of the world, creating as many untraceable accounts as required has been convenient for hackers like ME. After the compromise of Stan Swamy’s email—likely the first, and by far the most successful, attack—ME’s targeting of the Elgar Parishad accused and their closest associates became even more explicit.

ME used Swamy’s email to cast a snowball net specifically targeting his friends and confidants within the left-intellectual sphere, ensuring that future victims received the infected emails from those they trusted. By early 2016, the emails of Harshal Lingayat, Arun Ferreira, and Prashant Rahi were brought into the mesh of compromised identities. It was through these emails that the second computer hard disk surrendered by the prosecution for forensic cross-verification was compromised: that of Surendra Gadling in February 2016.

The compromise of Gadling’s system was also chronologically the second of the three attacks so far investigated and reported, shortly followed by that of Rona Wilson, in June 2016. The nature and timeline of these three attacks relative to each other, which we shall call the Arsenal-investigated attacks based on the agency that uncovered them in depth, are particularly essential to understanding the workings and modus operandi of ME. (A detailed reference of all the incriminating documents and forensic reports is available here.)

Like with Gadling, the method of delivery of the virus to Wilson’s system also involved the hackers posing as a trusted confidant, this time co-accused Varavara Rao. Hany Babu’s email was also hacked at an unconfirmed point in the chain of events.

Phase Three: Occupation—I Spy With My Little Eye

After the successful infiltrations of the systems of Swamy, Gadling, and Wilson—in that order—began a long refrain of intense and shocking surveillance. Entire drives were mirrored and synchronised with the hackers’ virtual servers. Everything from typed documents, shared and received emails, and browsed websites to sensitive data like passwords and account logins was logged and monitored, for months on end. Mark Spencer, the president of Arsenal Consulting, examined all three accused persons’ devices and published five detailed reports on them between 2021 and 2022, after the first was sought by Rona Wilson’s defence team. In the reports, Spencer writes, “It should be noted that this is one of the most serious cases involving evidence tampering that Arsenal has ever encountered, based on various metrics which include the vast timespan between the delivery of the first and last incriminating documents on multiple defendants’ computers.”

In her book, The Incarcerations: Bhima Koregaon and the Search for Democracy in India, Alpa Shah writes that Spencer was initially very sceptical of the possibility of malicious activity. He found it absurd that such a blatant operation could go undiscovered in even the most elementary forensic analyses, especially in a case as high profile as this one. “I expected we would quickly rule in or out whether there was suspicious activity on Rona Wilson’s computer,” Spencer told Shah. “I was leaning towards ruling out. What I did not expect in any way was to be walking into a massive cesspool of attack infrastructure, aggressive surveillance, and electronic evidence tampering.”

By far the most extensive of the three attacks was the one detected against Stan Swamy. It comprised not one but three separate NetWire campaigns spread across 12 distinct virus samples, over the course of a colossal 52-month duration. The infiltration of his computer led to the illicit transfers of the contents of 13 removable storage devices containing over 24,000 files, followed by a failed clean-up, with a trail leading all the way up to the eve of seizure of his devices by the Pune Police in June 2019.

In comparison, the attack on Gadling’s computer was shorter—prematurely cut off in November 2017, after 20 months of infiltration, due to a fortuitous decision to reinstall the computer’s operating system. It spared him another five months of being hacked, but the delivery of plentiful incriminating documents to his computer had already taken place. The attack on Rona Wilson’s system lasted 22 months, right till one week before the seizure of his devices on 17 April 2018.

While ME conducted these long-term surveillance operations via NetWire, another nefarious malware was making its way through the circuit of its chosen victims—predominantly human-rights activists, lawyers, and left-leaning intellectuals. Only this one was neither commercially available nor operated by low-skilled professional hacker networks. The infamous spyware Pegasus, of Israel’s NSO group, sold exclusively to governments and their militaries as the subject of much ethical controversy, was successfully inserted into Rona Wilson’s presumed iPhone in July 2017. This was around the same time when the deliveries of incriminating documents to all three systems had begun. Another curious link between the Pegasus and ME attacks was that just like the latter, the Pegasus infection also stopped in April 2018, just before the first round of Pune Police seizures.

In August 2021, Arsenal confirmed the Pegasus infection, casting unshakeable doubt on a governmental role in the cyber conspiracy. A year later, the Supreme Court also stated that at least five out of 29 allegedly compromised phones were infected with some malware, but the then chief justice NV Ramana noted that the central government did not cooperate with the technical investigation, and as such the use of Pegasus could not be confirmed, putting the lid on the matter.

Phase Four: Delivery—Fabrication and Plantation of Incriminating Evidence

On 3 November 2016, ME used the remote access feature of NetWire for the first time for the creation of a file on a compromised system, as opposed to extraction or observation that had been conducted till then. The attacker created a hidden folder called “Rbackup” on Rona Wilson’s computer. Wilson’s defence team had provided Arsenal with a list of the “top ten” incriminating documents that the Pune Police relied upon to build a case against him, as well as “24 additional files of interest.” The forensic analysis revealed that it is into this “Rbackup” folder that the attacker illicitly planted all 34 documents—the top ten incriminating files as well as the 24 additional ones— over the course of a year between March 2017 and 2018.

Similar hidden folders were created on the systems of Stan Swamy and Surendra Gadling as well, with the timings of all three operations overlapping significantly. In all three cases, Arsenal found that the users of the computers—Wilson, Gadling and Swamy—had never interacted with the incriminating files, or the hidden folders containing them, at all.

ME’s process for the delivery of files was elementary and extremely traceable, enough that Arsenal was able to recreate their entire history of illicit activity from the clone files alone, of which Gadling’s had been rebooted completely down to the operating system:

- First, ME would create a folder nested deep within other infrequently used folders on the system (determined easily after the intense monitoring activity) and set it to “hidden.”

- Second, ME would deliver “.rar” archives, which are compressed folders, containing documents either related to the banned CPI (Maoist) or downright fabricated to indicate authorship of the accused, into the hidden folders.

- Third, ME would temporarily deploy a version of WinRAR (a tool to unpack compressed files), unpack the .rar archives, and then delete both the archives and the temporarily deployed version of WinRAR.

This fairly convoluted process served as ME’s modus operandi for the delivery of incriminating files with all three attacked systems, and consequently left behind an avalanche of evidence of illicit activity due to its unsophisticated nature. Using logs left behind by the use of the virus, the Windows file system, as well as the all-too-traceable history of WinRAR use, Arsenal was able to retrace nearly every step of the attacker’s digital activity down to the millisecond when they were performed. In addition, ME also made many grave errors, including a desperate clean-up effort (elaborated in a later section) that was cut short due to an unsuitably timed shutdown of Swamy’s system.

Another error was a botched file delivery between Wilson and Gadling’s systems. On 22 July 2017, ME used the trojans in Gadling’s and Wilson’s respective systems—both compromised at this time—to remotely access them simultaneously for the purpose of delivering incriminating documents. Likely in confusion, ME accidentally delivered a file named “CC –Financial Policy.docx” to Wilson’s system, though it was in fact intended to be delivered to Gadling’s computer, where it would be eventually discovered. Noticing their error, ME quickly delivered the file to Gadling’s system and deleted it from Wilson’s, the whole process taking about twenty minutes.

Despite small—but significant—errors like this one, ME’s access either to legitimate documents related to the banned CPI (Maoist), or to sufficient knowledge about them to fabricate details themselves, or to both, indicate the involvement of a powerful and resourceful entity. As Spencer stressed repeatedly in each of Arsenal’s five reports, “the attacker had extensive resources (including time).” After Arsenal’s involvement, the modus operandi of evidence fabrication, incriminating document delivery as well as the apparent high-profile nature of the attack drew the attention of an independent, California-based threat security intelligence firm, SentinelOne and their forensic body SentinelLabs.

In September 2021, a report by Juan Andres Guerrero-Saade and Igor Tsemakhovich for SentinelLabs covered in great detail the operations of a Turkey-based APT whom they named EGoManiac, due to the repeated use of the initials EGM in their malware infrastructure. Like in the case of ModifedElephant, EGoManiac’s attacks involved the infiltration of victim systems—in this case a group of Turkish journalists—using RATs to implant incriminating documents that were then used to justify arrests by the Turkish National Police and wrongfully incarcerate the victims for several years.

In both cases, Arsenal Consulting played a key role as an independent agency that revealed the true cyber-forensic extent of the attacks when the state agencies did not. In fact, following Sentinel’s report on EGoManiac, Arsenal Consulting alerted them to the targeted attacks on HRDs in India. Guerrero-Saade, alongside another Sentinel threat researcher Tom Hegel, conducted an extensive cyber forensic examination of the nature of digital espionage in India, ultimately identifying a common attacker they named the ModifiedElephant APT.

ModifiedElephant’s case in isolation may seem sensational and absurd, but is nowhere near as reviling as the reality that is the emergent sector of state-sponsored cyberespionage and conspiracy, casting doubt on the very premise of electronic devices being brought into courts as evidence in cases involving national security.

“A threat actor willing to frame and incarcerate vulnerable opponents is a critically underreported dimension of the cyber threat landscape that brings up uncomfortable questions about the integrity of devices introduced as evidence,” says the Sentinel report. “[ModifiedElephant] has operated for years, evading research attention and detection due to their limited scope of operations, the mundane nature of their tools, and their regionally-specific targeting.”

Phase Five: Seizures—A Desperate Clean-up Attempt

With the exception of the attack against Gadling—cut short when he had Windows reinstalled on his system, ostensibly by a professional for unrelated technical troubles—the two other ME attacks on Wilson and Swamy ended with suspicious last-minute activity on the victims’ devices. In Wilson’s case, this constituted a close monitoring of file system logs well into the night of 16 April—the eve of the seizure—as well as a retreat of Pegasus from his iPhone six days earlier.

In Swamy’s case, to say that the last-minute activity was suspicious would be an understatement. On 11 June 2019, a day before the seizure of his devices, ME began to perform an extensive clean-up of their malicious activities using NetWire, including crude anti-forensic activity, which was abruptly interrupted by the user—presumably Swamy—unknowingly shutting down the computer at 9 pm, right before the virus could be set up for a so-called self-destruction. The clean-up involved, broadly, the deletion of traces of surveillance and incrimination activity; the creation of “noise” to obfuscate illicit activity; and renaming malicious folders to unsuspicious names such as “Desktop” and “Opera.”

The deletion of the traces of surveillance activity included one massive deletion of 14,313 files from a hidden staging area used for siphoning files to the hackers’ servers, using a command for “forceful and quiet” deletion. Similarly desperate commands were used for the creation of “noise” in two folders where malicious activity had taken place, ignoring errors and suppressing file safety prompts. Ironically, the desperate deletions of files and activity logs did not prevent Arsenal from reconstructing the logs of the deletions themselves; another crucial failure in ME’s efforts.

It should be reiterated here that ME’s attack on Swamy’s computer was far more extensive than that on either Wilson or Gadling; it lasted more than a year past the activity on Wilson’s system and nearly two years more than that on Gadling’s. Both the number of NetWires deployed to Swamy’s system and their versions were more advanced than those used in either of the other attacks, therefore it is not extraordinary for ME’s campaign against Swamy to possess some unique characteristics. However, it is nonetheless noteworthy that such a desperate, and intense attempt at clean-up would be made in his system specifically, when there was absolutely no effort towards erasing their tracks in the other two systems, where the evidence delivered was far more severe, like the infamous “Ltr_1804_to_CC.pdf” on Rona Wilson’s system that ideates a plot to assassinate the prime minister and a sensational plan to purchase arms and ammunition.

In this context, it is all the more relevant that the seizures of Stan Swamy’s devices took place over a year after the first wave of arrests, giving ample time for the grains of the prosecution’s sand-built case against Gadling and Wilson to crumble. After April 2018, Pune Police had quickly emptied its hand of digital evidence against the defendants, having planted the files recovered from Wilson’s system into the media, and in doing so attracted scrutiny from both the relevant superior courts and the global citizenry at large.

By mid 2019, before the police raided Swamy’s home, the defence teams of Wilson and Gadling had already begun to push for the provision of device clones for their analyses—a push the prosecution knew they could not continue blocking for too long. The threads of ME’s painstakingly built tapestry of digital fiction had already begun to unravel. So, in all likelihood, the clean-up on Swamy’s computer was a desperate, last-ditch effort at holding together the fabricated plot.

Who is ModifiedElephant? The Discovery of a Direct Link to the Pune Police

It is crucial to note that in all three cases, the deliveries of incriminating files had already begun months before the Bhima Koregaon violence took place. And yet, the delivery of files pertaining to Elgar Parishad or any alleged conspiracy around it did not begin until January 2018, after the registration of the FIR against Sambhaji Bhide and Milind Ekbote. By all indications, then, the attacker was already planting the seeds for their victims to be framed in some kind of ‘Maoist links’ case, same as was done to the six targeted in the Gadchiroli case. It was only after the Bhima Koregaon violence took place that the attacker began making efforts to implicate them in the same, as a convenient retrospective. But how and why did this shift of strategy take place?

Pulling on that thread unravels a slew of countless more incongruences nested within the unknown and elusive motivations of ModifiedElephant: why were the BK-16 and other human rights activists the target profile for ME’s attacks? Considering that the actor made no attempts whatsoever to use them for financial gain or fraud, despite having unrestricted access to the private information of their victims and their online identities, what was their incentive? A low-skilled or unsophisticated attack though it may have been, it is inarguable that the malware infrastructure run by ModifiedElephant for this campaign was a competent, technically qualified, and professional one, by cyber threat standards; so who employed them? Why didn’t they do a better job of establishing a digital trail of use of the incriminating documents, why didn’t they do a better job of hiding their own illicit activity? And last but certainly not least: how did they know to cease the figurative cyberfire just ahead of the infected systems being raided and seized, before the raids were finalised?

Each of these questions points toward a damning, if obvious, conclusion: ModifiedElephant had direct links to the state and law enforcement, and was operating either on their directions or in their favour whilst maintaining some form of communication with them in real time. Though the signs all indicated this, such as the state forensic labs’ obfuscation of the malware attacks and the curious parallels in the investigative procedures and the illicit activity, it was not until June 2022 that it went from an obvious speculation, to confirmed fact.

In an exclusive report by WIRED, four independent sources revealed a shocking forensic discovery. In their report for SentinelLabs, the researchers Guerrero-Saade and Hegel had stopped short of identifying the actor behind ME. But the WIRED report noted that the researchers had subsequently worked with a security analyst at a yet unnamed email provider and discovered that there was a recovery email and a recovery phone number added to the compromised emails of Wilson, Gadling and Babu. This would allow the attacker to regain control to the emails if the password was changed. “To the researchers’ surprise, that recovery email on all three accounts included the full name of a police official in Pune who was closely involved in the Bhima Koregaon 16 case,” the WIRED report noted.

WIRED then approached two other security researchers, who identified the recovery phone number as being associated with the same police official in multiple open-source police databases as well as a leaked TrueCaller database. The researchers also found that the WhatsApp photo for the recovery number was a selfie photo of the police official, which the report notes, was “a man who appears to be the same officer at police press conferences and even in one news photograph taken at the arrest of Varavara Rao.”

The WIRED report did not disclose the identity of the police official. But it is this crucial detail of the photograph with Varavara Rao that led the author Alpa Shah to identify the officer, which she then confirmed with the WIRED team as well.

The email and phone number belonged to none other than the investigating officer of the Elgar Parishad case for the Pune Police: Shivaji Pawar, himself.

The End of NetWire, A Lead (to) for the Future

In March 2023, the United States Federal Bureau of Investigation seized the domain named “worldwiredlabs[.]com.” Around the same time, a Croatian national was arrested for administering the website, and a computer server in Switzerland was seized for hosting much of its material infrastructure. This is the website on which NetWire had been sold for over a decade, since 2012.

In many ways, the evolution of NetWire and ModifiedElephant grew in parallel. They both started out in 2012, forming relatively low-threat parts of high-threat infrastructures, and grew into behemoths in the world of cyberespionage. The rise and evolution of NetWire concurrently supported and enabled the ambitious expansion of ModifiedElephant’s noxious campaigns against innocent activists and critical voices within India’s political sphere; its downfall is the best lead this country has toward uncovering what may be an even larger nexus of cyber-threats that endanger the fabric of India’s democracy.

With NetWire out of the picture, ModifiedElephant is likely to switch over to DarkComet, another commercial Trojan they occasionally and sparingly made use of in their campaigns. But with or without options, the walls are closing in; the myriad of indicators and fingerprints already picked up by Arsenal from the three defendants’ devices, and in all likelihood also Hany Babu’s, has been expanded into a barrage of indicting markers in the Sentinel report. Additionally, the Sentinel report also mentioned another APT called SideWinder, which has been acting alongside ModifiedElephant, targeting the same profile of victims, thus further expanding the suspected pool of state-sponsored threat actors.

A year after Pandu Narote died in custody of a treatable illness and seven months before Saibaba passed away from a complication from conditions exacerbated in prison, the Bombay High Court acquitted the Gadchiroli six. Coming full circle from the genesis of the BK-16 myth with the convictions of the Gadchiroli six in March 2017—the same time incriminating documents began to be planted into the systems of Wilson, Gadling and Stan Swamy—the judgment upon which the entire case mounted against the BK16 rested was overturned in March 2024 Over 10 years after they were arrested, following the remarkable final hearing of Mahesh Kariman Tirki and others, the six accused of having “Maoist links” were deemed innocent on all counts and released due to invalid prosecution sanctions, stock witnesses, and a complete absence of credible evidence. The electronic evidence against them was dismissed due to egregious procedural violations, casting a reasonable doubt over the possible tampering.

The foundations of the Elgar Parishad/Bhima Koregaon conspiracy case are, therefore, deemed to crumble under the weight of time and global scrutiny. Slowly but surely, the truth behind the impressive, monstrous amounts of lies concocted from sheer, commendable imagination has been coming out into the public domain. If the case still stands today, with six of the BK16 still behind bars, it could only mean that our superior courts have yet to abandon their leniency towards the law-enforcing wing of the state. As Mahesh Kariman Tirki and others presupposes, it is possible for justice to be drawn closer than could be imagined with a distant and protracted trial, if only their Lordships would care to seriously consider a thorough appraisal of the case as a whole, hopefully through a suo motu quashing petition. All that’s left to do then, is wait for judgement day to come.

This is the third report in a three-part investigative series on the Elgar Parishad/Bhima Koregaon case. Read part one here and part two here.

SUPPORT US

We like bringing the stories that don’t get told to you. For that, we need your support. However small, we would appreciate it.