Seventy years after the Indian subcontinent gained independence from the British Raj and was divided into the newly-formed countries of India and Pakistan, the shadows of the past still linger. The State of Jammu and Kashmir (J&K), often defined as the “unfinished business of partition,” remains an unresolved issue and has been in a situation of perpetual war.[i] As their land is the primary bone of contention between the two South Asian giants, the people of J&K have grown up in the most militarized zone in the world.[ii] Two major wars were fought over it, in 1948 and 1965, and their harsh effects have left an imprint on the people of the border areas, shaping their collective identity and memory.

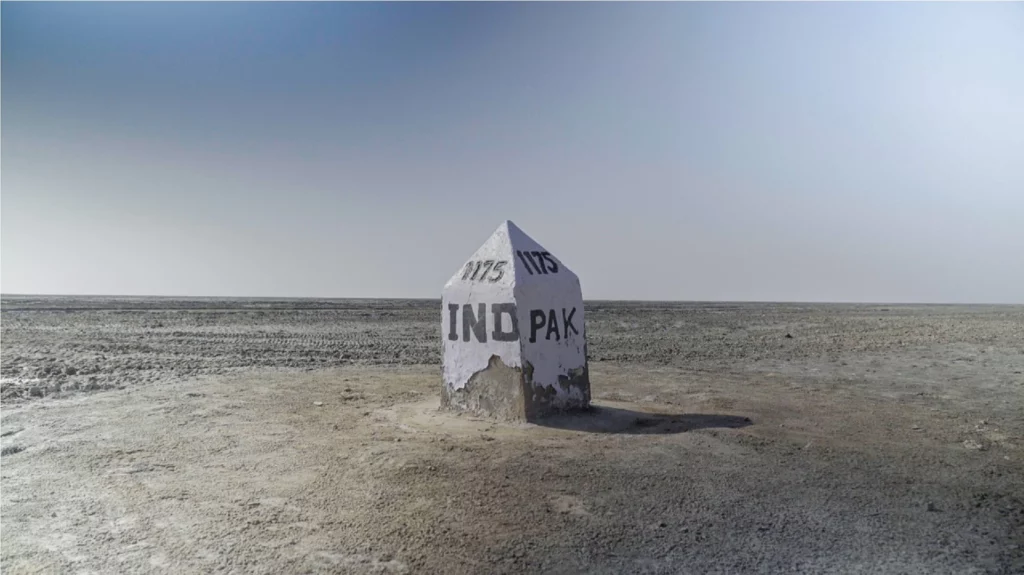

J&K is surrounded by two sets of borders: the Line of Control (LoC) and the permanent international border. After the 1948 war, a delegation of military representatives from both countries met with the Truce Sub Committee of the United Nations in Karachi to agree on a ceasefire line that would divide the State in two and would be controlled by the military of both countries. This meant that one part of the region went to Pakistan, Azad Jammu and Kashmir, and the other to India, Jammu and Kashmir. After the 1971 war, the Simla Agreement renamed the ceasefire line as the Line of Control: even though this is demarcated on official documents, on the ground there is still no clarity about the actual border thus resulting in frequent stand-offs between the two armies.

Since then, the people of both regions have been living at the mercy of the highly militarized politics of the two nations: artillery, army posts every two kilometres and regular armed confrontations are normal sights and children grow up knowing how to differentiate between the sounds of a mortar shell and that of artillery. During any kind of unfavourable political development between the two countries, the outcome is often heavy shelling along the border. Recently, cross-border firing happened in the month of July ahead of Indian Government’s decision of abrogating the special status of J&K and many more incidents had been reported since.[i]

Amidst the clamor of politicians of both sides glorifying their armies, media houses screaming victory slogans and citizens priding over their nation, the voice of one particular group often gets sidelined: that of the people living near the border areas. These people are fighting a battle they did not chose. Generation after generation, they have gone through immense pain, yet their voices are deliberately ignored and their miseries termed as “collateral damage” for the supposed ‘greater good’ of national security.

The lives of these people are never at peace.

John Galtung, the founder of the Peace Research Institute in Oslo, differentiates between negative and positive peace.[ii]The former is the meagre absence of violence, while positive peace involves structural transformations which have a long-term and holistic impact. The people of these villages do not just suffer during war or regular skirmishes between the military of the two countries; even in the absence of such direct physical violence, these regions are always living under an uncertain economic situation and restriction of movement.

At the onset of the war over Jammu and Kashmir in 1948 and then again in 1965, the residents of the borderlands ran for their lives. Families found shelter in different places and, once the war was over and the ceasefire line drawn, many people found themselves stranded in what had then become Pakistan – separated by a newly created border from their brothers, sisters and parents. Although finding oral history records and direct witnesses is now difficult, the second generation of those who had suffered this “other partition” clearly remembers the tales narrated by their fathers and mothers. One such person is Abdul Rashid Khokhar, a resident of Dringla village, Teethwal, Kupwara.

“Uss waqt sabko sirf chupne se matlab tha, humme kya pata tha vo Azad Jammu and Kashmir bannjayega, aur humare rishtadar humse door chale jayeinge” (At that time, all that people cared for was running to save their lives. Who knew where they hid and that in a day’s time it would become Pakistan and our relatives would be gone forever), Abdul Rashid Khokhar says while showing me a photo of his uncle, who was left behind in Azad Jammu Kashmir after the 1947-48 war between India and Pakistan. Abdul Rashid’s father was separated from his only brother in 1947, when he ran to a nearby village in Karnah to find shelter from the ongoing war. Even after the war was over, the brother could not return to his native village because by then a ceasefire line was agreed upon. His family and land were on the other side of the Line: that is, in India. For 50 years he stayed in touch with his brother through letters and postcards until, crossing at Teethwal in India, he finally visited his village for the very first time. “I remember how everyone just started crying and wailing right on the bridge. He died a few years later, it seems he was just waiting to visit his land one last time,” recalls Abdul Rashid Khokhar.

“How strange is it? My relative stands only a few feet apart and I still have to apply for a LoC permit, wait for six months, and only then can I see them in Pakistan.”In Kupwara, almost every household has relatives in Pakistan; for them, a trip to Pakistan has become a kind of a holy pilgrimage. Divided by the Kishanganga River, the people of Teethwal and those in the villages that are now in Pakistan wave at each other from across the river. If a person dies on either side, an announcement is made in the respective mosques for people on the other side to also hear – this is how people would be informed of their relatives’ deaths when phone calls would not get through from Pakistan-administered Kashmir to India-administered Kashmir and vice versa.[iii] This is how Mir Hussain Khokhar, a resident of Teethwal, heard about the death of his uncle.

People from both sides would assemble along the river and throw across letters wrapped around small stones: the letter would mention the name of their relatives, and if anyone would know them, they would tell them to come by the river. “How strange is it? My relative stands only a few feet apart and I still have to apply for a LoC permit, wait for six months, and only then can I see them in Pakistan,” says Anzaar, a member of a family that has been separated for three generations.

When militancy in Kashmir reached its peak in the 1990s, local residents would be subjected to heavy interrogations regardless of whether they would be related to a militant or not.[iv] “I remember how they used to enter our houses at any point of the day or the night, smash our doors and windows with wooden sticks, empty our wardrobes, lock us up in one room,” recalls Sakina Begum, a resident of Teethwal village, Kupwara.

Some residents had enough of the constant abuse and wanted to escape to the other side, in Pakistan, a mere fifteen-minute walk from their house through the dry borderline.

Mir Hussain Khokhar’s sister’s entire family escaped to Pakistan from Amroohi (in Karnah, Kupwara) which is a ten-minutes away from Pakistan-administered Kashmir. In 2007 Hussain went to Pakistan to meet his sister. “Their living condition was not good and time and again I tried to persuade them to return. But what will they return to? Their daughters are married there, their sons study there. It is their necessity to live in Pakistan. My heart yearns for my sister and my nieces and nephews.”

“Sadana Pakistan te na hindustan” We belong neither to Pakistan nor to India”

“The situation was such that no one could escape this. We Kashmiris from the border villages who had escaped – we were used in Pakistan. They diluted the entire movement of freedom that was going on in Kashmir,” Rafiq Butt said. Rafiq Butt, 45, a tall and well-built man, returned to his hometown Saujiyan, in Poonch (J&K) in 2015. In 1992, at the age of 13, he escaped with his family to Pakistan. During the 1990s, as a reaction to the unjust Indian policies in Kashmir, a number of young boys and men joined militant outfits, some home-grown and some externally sponsored. Many crossed into Pakistan for training, leaving behind their families who would then be often tortured by the local police, intelligence agencies and the Army in order to obtain information about the militants. Rafiq Butt’s elder brother had joined Hizbul Mujahideen, a militant outfit sponsored by Pakistan. In retribution his father and two older brothers were tortured for several months. Then one night, the entire family (13 members in total) decided to run away to Pakistan carrying only dates and kulcha. “I clearly remember, it took us three days to walk to Pakistan. We had carried nothing with us and whenever us kids felt thirsty we would fill up our father’s karakoli cap with water and drink it. Once we reached the first Pakistan army post, they welcomed us, fed us with good food, and then escorted us to the nearest police station.” Rafiq Butt also joined Hizbul Mujahideen in 1998. “The situation was such that no one could escape this. We Kashmiris from the border villages who had escaped – we were used in Pakistan. They diluted the entire movement of freedom that was going on in Kashmir,” Rafiq Butt said

“Now that I have returned, although I have found respect from my long-lost neighbors and relatives, I still am not eligible for many government benefits. In Pakistan too, we Kashmiris are referred to as muhajirs or refugees, and we are not full Pakistani citizens. Sada na Hindustan na Pakistan. I used to live in Kashmir there, and here also I am in Kashmir. We are an independent nation.”

There was a court case filed against Rafiq Butt and his family to review and legalize their return. The case continued for one and a half years, after which they were made eligible for an Aadhaar card and were declared state subject. Rafiq now runs a tailoring business in the town of Mandi, Poonch.

“Our children live with a lingering fear of bullets and shelling”

Termed as collateral damage, the lives of people, the loss of their property and livestock is almost never talked about. Neither are the severe injuries and even the occasional death of local residents caused by the skirmishes between the two armies that can start at any time, without prior warning. Some of these stories make it to the news, others are not fortunate enough to be even recorded.

In the last week of July 2019, the situation along the border areas worsened: sectors that had not witnessed shelling and firing since the ceasefire of 2003, were hit again. “We had never seen or heard artillery bombs in this area. But yesterday from 2:30 pm to 4:30 pm, there was continuous firing of artillery bombs. It seemed like an earthquake, that’s how bad the earth was shaking,” says Anzaar, a resident of Dringla, Teethwal, Kupwara.

According to the locals, however, when Indian forces aim at Pakistani territory, many Indian villages also fall within their range and often become a target themselves. “I could not believe my eyes when I saw a 10-day-old baby with his intestines out of his body,” said a local who sent me photos of a family injured due to firing in Shahpur village in Poonch on the 28 July 2019. The infant must have died on the spot, but the hospital announced it officially after 12 hours.

“We can tell if the firing has been initiated by India or Pakistan from the range of the sound of artillery. And this time it was India that initiated it,” a resident of Teethwal said. Most of the times, the origin of a mortar shell remains unknown as bullets from either side can hit them. According to the locals, however, when Indian forces aim at Pakistani territory, many Indian villages also fall within their range and often become a target themselves.

When I reached, it seemed like I had entered a war videogame. It was surreal: no houses, just army posts; no cars, just army trucks; no civilians, just army men. On 15 July 2019 I visited the Balakote sector in Poonch; as the day before there had been heavy cross-border shelling, local residents recommended against it, but I decided to go anyways. When I reached, it seemed like I had entered a war videogame. It was surreal: no houses, just army posts; no cars, just army trucks; no civilians, just army men.

The Balnoi sector of Poonch had also suffered from a stand-off between the two armies in February 2019. This is not a novel phenomenon. Most border villages in Kupwara, Uri and Poonch have never had proper bunkers to find refuge during cross-border shelling and most people use the small mud-houses constructed for their animals as shelters. “Whenever firing starts we leave our shops unattended in haste, and hide in old the houses of the village,” said a resident of Saujian, Poonch. These old houses are made of stone and it more difficult for mortar shells to pass through the walls and they also protect against the noise of the firing. “Now many people are constructing new houses out of bricks and cement. The old houses are breaking down. I just wonder where we will hide after a few years when none of these houses will be left,” said Neha, a 20-year-old college student resident of Saujian, Poonch.

“Bomb! Bomb!” This is what children living along the LoC and the International Border grow up with: they know no other life. The army and the Border Security Forces, however, build their makeshift bunkers right next to the houses from where they shoot. “It is hard for us to sit in our homes when they start firing. It is very loud. Our babies and children suffer the most. But what to do? We have no other option,” said Zahida Begum, a resident of Saujian, Poonch. A girl from Arnia, in R.S Pura, who witnessed her first shelling in 2015 when she was 4 years old, now gets scared every time she hears a loud noise and cries: “Bomb! Bomb!” This is what children living along the LoC and the International Border grow up with: they know no other life.

Neha, a young school teacher, who also lives in Arnia tells me how they are scared to go to into the makeshift shelters in community halls and schools whenever the firing starts. “There is no concept of gender segregation there. Same halls, same bathrooms are to be used by men, women, girls and boys. How can we go there, you know the times are not trustworthy.”

Often when firing starts, parents send off their children to other villages away from the border, but they have to stay back to tend to their livestock. “Our land and our animals are the only sources of income for us. We have nothing else. I would any day prefer to save my cows over myself during a firing incident,” said Neha’s mother. Most of the population living along the borders rely on agriculture and on their livestock for their livelihood. Few are temporary employees in the government, while others have small shops.

Saujian in 2016 witnessed heavy shelling. Allegedly, Pakistani forces targeted the market where the Indian forces used to store their oil. The entire area burnt down. The shopkeepers re-constructed the market from scratch with their own money, borrowing from relatives or getting bank loans.

As the LoC is not a permanent border, both countries keep changing the demarcation and, as a result, many people have lost their land to this boundary war. As the LoC is not a permanent border, both countries keep changing the demarcation and, as a result, many people have lost their land to this boundary war. In most places, the LoC is marked with a barbed wire. The villagers’ land is often occupied by border forces without paying any compensation or allocating a different piece of land.[v] “We have sold our animals because there is no land left for grazing,” said a resident of Saujian, Poonch.

Considering such harsh conditions, it is difficult to understand why people are still living there. For most residents, however, their lives are rooted in those villages and their livelihood depends on the land. Many people have been displaced internally and relocated from one border village to another. In the 1965 war, Pakistan’s main target was the Akhnoor sector in Jammu.[vi] Gulabo Ram and his family were relocated from Akhnoor and given land in Treva, R.S Pura, two kilometers away from the International Border. “It took us ten days to walk from Akhnoor to Arnia and yet we were relocated to a place that too witnessed thousands of firing incidents since then,” recalled Gulabo Ram. Last year, in the month of May, there was an unprecedented firing that lasted for four hours.

Apart from the firing and artillery shelling, the residents along the LoC and the International Border also live with the uncertainty of anti-personnel landmines. Most of the landmines placed by the Army are signaled, but occasionally they are planted randomly or may drift from their original position for the rain or a snowfall. Residents, especially children, are very frequently the unintended victims of these mines. In 2017, Khalid, a nine-year-old boy, went to a nearby field to collect wood to fuel the traditional stove in his house. Little did he know that he had picked up a landmine along with the wood. The landmine exploded in the stove when he fired it and Khalid lost the right eye, leg and arm.

“No! Media is not authorized to enter this gate. Please leave your cameras and phones here.”

There are villages along the LoC where no one except residents, doctors and government employees are allowed to enter. Media are among those who are not welcome. I wanted to go to Amroohi in Karnah, which I had already visited in 2018. However, in July 2019, the men at the Army checkpoint asked me to get permission from the Sub District Magistrate (SDM) office and the brigadier stationed in Tangdhar. Despite having managed to get the required permission, the Commanding Officer of that unit refused to let me go through the gate that locked the village. “They don’t want outsiders to know what they have been doing inside the villages. They don’t want the secrets to be leaked out,” said my local guide.

Churranda had a melancholic feel to it; the media has rarely been to this village and when they did, they were handed a list of dos and don’ts by the Army. Similarly, in a village in Uri, Churranda, I had to leave my camera, phone, notebooks and pens behind. Churranda had a melancholic feel to it; the media has rarely been to this village and when they did, they were handed a list of dos and don’ts by the Army. A few years ago, according to the locals, the Army burnt down many houses just to clear the land in order to plant anti-personnel landmines. These families now either live in their neighbors’ and relatives’ houses or have borrowed money to build new small houses.

These villages are enclosed with a gate that is locked from 7 pm till 7 am. In these twelve hours the Army personnel guarding the gate is not available and if there is any medical emergency the local residents are left stranded. In the occurrence of cross border firing, the administration waits for a day and only then, if the firing continues, would evacuate the villages. During such skirmishes, if a villager is injured he would not be able to reach a nearby hospital as all the roads are blocked by the armed forces. Manzoor, a school teacher from Balakote village in Poonch, recalls an incident when a school bus got stuck amidst a sudden cross-border firing and a senior teacher got injured. They could not transport him to the hospital on time, and he succumbed right there.

Life along the borderland is harsh and difficult to understand. A couplet by Pakistani poet Jaun Eliya sums it well: “Jo Guzaarina Jaa sake humse, hum ne vo zindagi guzaari hai.” (This unbearable life, yet I have carried the burden throughout.)

References

[i] Naveed Siddiqui. 31st July 2019 Increased ceasefire violations by Indian troops ‘indicate their frustration’, says DG ISPR. https://www.dawn.com/news/1497272

Abhishek Bhalla, 30th August 2019. Truce broken 222 times by Pakistan in August. https://www.indiatoday.in/mail-today/story/truce-broken-222-times-by-pakistan-in-august-1593266-2019-08-30

[ii] John Galtung, 7th May 2015. Violence, Peace, and Peace Research, http://www.jstor.org/stable/422690

[iii] Till now, normal cellular phone calls do not get through from India-administered Kashmir to Pakistan-administered K, while people from Pakistan can call.

[iv] During that time, people from India-administered Kashmir would cross to the other side for arms training. Tariq Bhat, 2nd March, 2019From Heaven to Hell. https://www.theweek.in/theweek/cover/2019/03/02/from-heaven-to-hell.html

[v] Residents of Balakote village in Poonch are fighting a case in High Court asking for a compensation for their land occupied by the Border Forces.

[vi] Anaz Zakaria, 7th August 2018 Between the Great Divide: A Journey into Pakistan-Administered Kashmir. Harper Collins India.

[i] Scroll, 8th Sep 2015. Kashmir is the ‘unfinished business of Partition’, says Pakistan Army Chief. https://scroll.in/article/754127/kashmir-is-the-unfinished-business-of-partition-says-pakistan-army-chief

[ii] Rani Singh, 12th July 2016. Kashmir: The World’s Most Militarized Zone, Violence After Years of Comparative Calm. https://www.forbes.com/sites/ranisingh/2016/07/12/kashmir-in-the-worlds-most-militarized-zone-violence-after-years-of-comparative-calm/

Nawal Ali is a social activist, an independent researcher and a photographer from Kashmir.

Seventy years after the Indian subcontinent gained independence from the British Raj and was divided into the newly-formed countries of India and Pakistan, the shadows of the past still linger. The State of Jammu and Kashmir (J&K), often defined as the “unfinished business of partition,” remains an unresolved issue and has been in a situation of perpetual war.[i] As their land is the primary bone of contention between the two South Asian giants, the people of J&K have grown up in the most militarized zone in the world.[ii] Two major wars were fought over it, in 1948 and 1965, and their harsh effects have left an imprint on the people of the border areas, shaping their collective identity and memory.

J&K is surrounded by two sets of borders: the Line of Control (LoC) and the permanent international border. After the 1948 war, a delegation of military representatives from both countries met with the Truce Sub Committee of the United Nations in Karachi to agree on a ceasefire line that would divide the State in two and would be controlled by the military of both countries. This meant that one part of the region went to Pakistan, Azad Jammu and Kashmir, and the other to India, Jammu and Kashmir. After the 1971 war, the Simla Agreement renamed the ceasefire line as the Line of Control: even though this is demarcated on official documents, on the ground there is still no clarity about the actual border thus resulting in frequent stand-offs between the two armies.

Since then, the people of both regions have been living at the mercy of the highly militarized politics of the two nations: artillery, army posts every two kilometres and regular armed confrontations are normal sights and children grow up knowing how to differentiate between the sounds of a mortar shell and that of artillery. During any kind of unfavourable political development between the two countries, the outcome is often heavy shelling along the border. Recently, cross-border firing happened in the month of July ahead of Indian Government’s decision of abrogating the special status of J&K and many more incidents had been reported since.[i]

Amidst the clamor of politicians of both sides glorifying their armies, media houses screaming victory slogans and citizens priding over their nation, the voice of one particular group often gets sidelined: that of the people living near the border areas. These people are fighting a battle they did not chose. Generation after generation, they have gone through immense pain, yet their voices are deliberately ignored and their miseries termed as “collateral damage” for the supposed ‘greater good’ of national security.

The lives of these people are never at peace.

John Galtung, the founder of the Peace Research Institute in Oslo, differentiates between negative and positive peace.[ii]The former is the meagre absence of violence, while positive peace involves structural transformations which have a long-term and holistic impact. The people of these villages do not just suffer during war or regular skirmishes between the military of the two countries; even in the absence of such direct physical violence, these regions are always living under an uncertain economic situation and restriction of movement.

At the onset of the war over Jammu and Kashmir in 1948 and then again in 1965, the residents of the borderlands ran for their lives. Families found shelter in different places and, once the war was over and the ceasefire line drawn, many people found themselves stranded in what had then become Pakistan – separated by a newly created border from their brothers, sisters and parents. Although finding oral history records and direct witnesses is now difficult, the second generation of those who had suffered this “other partition” clearly remembers the tales narrated by their fathers and mothers. One such person is Abdul Rashid Khokhar, a resident of Dringla village, Teethwal, Kupwara.

“Uss waqt sabko sirf chupne se matlab tha, humme kya pata tha vo Azad Jammu and Kashmir bannjayega, aur humare rishtadar humse door chale jayeinge” (At that time, all that people cared for was running to save their lives. Who knew where they hid and that in a day’s time it would become Pakistan and our relatives would be gone forever), Abdul Rashid Khokhar says while showing me a photo of his uncle, who was left behind in Azad Jammu Kashmir after the 1947-48 war between India and Pakistan. Abdul Rashid’s father was separated from his only brother in 1947, when he ran to a nearby village in Karnah to find shelter from the ongoing war. Even after the war was over, the brother could not return to his native village because by then a ceasefire line was agreed upon. His family and land were on the other side of the Line: that is, in India. For 50 years he stayed in touch with his brother through letters and postcards until, crossing at Teethwal in India, he finally visited his village for the very first time. “I remember how everyone just started crying and wailing right on the bridge. He died a few years later, it seems he was just waiting to visit his land one last time,” recalls Abdul Rashid Khokhar.

“How strange is it? My relative stands only a few feet apart and I still have to apply for a LoC permit, wait for six months, and only then can I see them in Pakistan.”In Kupwara, almost every household has relatives in Pakistan; for them, a trip to Pakistan has become a kind of a holy pilgrimage. Divided by the Kishanganga River, the people of Teethwal and those in the villages that are now in Pakistan wave at each other from across the river. If a person dies on either side, an announcement is made in the respective mosques for people on the other side to also hear – this is how people would be informed of their relatives’ deaths when phone calls would not get through from Pakistan-administered Kashmir to India-administered Kashmir and vice versa.[iii] This is how Mir Hussain Khokhar, a resident of Teethwal, heard about the death of his uncle.

People from both sides would assemble along the river and throw across letters wrapped around small stones: the letter would mention the name of their relatives, and if anyone would know them, they would tell them to come by the river. “How strange is it? My relative stands only a few feet apart and I still have to apply for a LoC permit, wait for six months, and only then can I see them in Pakistan,” says Anzaar, a member of a family that has been separated for three generations.

When militancy in Kashmir reached its peak in the 1990s, local residents would be subjected to heavy interrogations regardless of whether they would be related to a militant or not.[iv] “I remember how they used to enter our houses at any point of the day or the night, smash our doors and windows with wooden sticks, empty our wardrobes, lock us up in one room,” recalls Sakina Begum, a resident of Teethwal village, Kupwara.

Some residents had enough of the constant abuse and wanted to escape to the other side, in Pakistan, a mere fifteen-minute walk from their house through the dry borderline.

Mir Hussain Khokhar’s sister’s entire family escaped to Pakistan from Amroohi (in Karnah, Kupwara) which is a ten-minutes away from Pakistan-administered Kashmir. In 2007 Hussain went to Pakistan to meet his sister. “Their living condition was not good and time and again I tried to persuade them to return. But what will they return to? Their daughters are married there, their sons study there. It is their necessity to live in Pakistan. My heart yearns for my sister and my nieces and nephews.”

“Sadana Pakistan te na hindustan” We belong neither to Pakistan nor to India”

“The situation was such that no one could escape this. We Kashmiris from the border villages who had escaped – we were used in Pakistan. They diluted the entire movement of freedom that was going on in Kashmir,” Rafiq Butt said. Rafiq Butt, 45, a tall and well-built man, returned to his hometown Saujiyan, in Poonch (J&K) in 2015. In 1992, at the age of 13, he escaped with his family to Pakistan. During the 1990s, as a reaction to the unjust Indian policies in Kashmir, a number of young boys and men joined militant outfits, some home-grown and some externally sponsored. Many crossed into Pakistan for training, leaving behind their families who would then be often tortured by the local police, intelligence agencies and the Army in order to obtain information about the militants. Rafiq Butt’s elder brother had joined Hizbul Mujahideen, a militant outfit sponsored by Pakistan. In retribution his father and two older brothers were tortured for several months. Then one night, the entire family (13 members in total) decided to run away to Pakistan carrying only dates and kulcha. “I clearly remember, it took us three days to walk to Pakistan. We had carried nothing with us and whenever us kids felt thirsty we would fill up our father’s karakoli cap with water and drink it. Once we reached the first Pakistan army post, they welcomed us, fed us with good food, and then escorted us to the nearest police station.” Rafiq Butt also joined Hizbul Mujahideen in 1998. “The situation was such that no one could escape this. We Kashmiris from the border villages who had escaped – we were used in Pakistan. They diluted the entire movement of freedom that was going on in Kashmir,” Rafiq Butt said

“Now that I have returned, although I have found respect from my long-lost neighbors and relatives, I still am not eligible for many government benefits. In Pakistan too, we Kashmiris are referred to as muhajirs or refugees, and we are not full Pakistani citizens. Sada na Hindustan na Pakistan. I used to live in Kashmir there, and here also I am in Kashmir. We are an independent nation.”

There was a court case filed against Rafiq Butt and his family to review and legalize their return. The case continued for one and a half years, after which they were made eligible for an Aadhaar card and were declared state subject. Rafiq now runs a tailoring business in the town of Mandi, Poonch.

“Our children live with a lingering fear of bullets and shelling”

Termed as collateral damage, the lives of people, the loss of their property and livestock is almost never talked about. Neither are the severe injuries and even the occasional death of local residents caused by the skirmishes between the two armies that can start at any time, without prior warning. Some of these stories make it to the news, others are not fortunate enough to be even recorded.

In the last week of July 2019, the situation along the border areas worsened: sectors that had not witnessed shelling and firing since the ceasefire of 2003, were hit again. “We had never seen or heard artillery bombs in this area. But yesterday from 2:30 pm to 4:30 pm, there was continuous firing of artillery bombs. It seemed like an earthquake, that’s how bad the earth was shaking,” says Anzaar, a resident of Dringla, Teethwal, Kupwara.

According to the locals, however, when Indian forces aim at Pakistani territory, many Indian villages also fall within their range and often become a target themselves. “I could not believe my eyes when I saw a 10-day-old baby with his intestines out of his body,” said a local who sent me photos of a family injured due to firing in Shahpur village in Poonch on the 28 July 2019. The infant must have died on the spot, but the hospital announced it officially after 12 hours.

“We can tell if the firing has been initiated by India or Pakistan from the range of the sound of artillery. And this time it was India that initiated it,” a resident of Teethwal said. Most of the times, the origin of a mortar shell remains unknown as bullets from either side can hit them. According to the locals, however, when Indian forces aim at Pakistani territory, many Indian villages also fall within their range and often become a target themselves.

When I reached, it seemed like I had entered a war videogame. It was surreal: no houses, just army posts; no cars, just army trucks; no civilians, just army men. On 15 July 2019 I visited the Balakote sector in Poonch; as the day before there had been heavy cross-border shelling, local residents recommended against it, but I decided to go anyways. When I reached, it seemed like I had entered a war videogame. It was surreal: no houses, just army posts; no cars, just army trucks; no civilians, just army men.

The Balnoi sector of Poonch had also suffered from a stand-off between the two armies in February 2019. This is not a novel phenomenon. Most border villages in Kupwara, Uri and Poonch have never had proper bunkers to find refuge during cross-border shelling and most people use the small mud-houses constructed for their animals as shelters. “Whenever firing starts we leave our shops unattended in haste, and hide in old the houses of the village,” said a resident of Saujian, Poonch. These old houses are made of stone and it more difficult for mortar shells to pass through the walls and they also protect against the noise of the firing. “Now many people are constructing new houses out of bricks and cement. The old houses are breaking down. I just wonder where we will hide after a few years when none of these houses will be left,” said Neha, a 20-year-old college student resident of Saujian, Poonch.

“Bomb! Bomb!” This is what children living along the LoC and the International Border grow up with: they know no other life. The army and the Border Security Forces, however, build their makeshift bunkers right next to the houses from where they shoot. “It is hard for us to sit in our homes when they start firing. It is very loud. Our babies and children suffer the most. But what to do? We have no other option,” said Zahida Begum, a resident of Saujian, Poonch. A girl from Arnia, in R.S Pura, who witnessed her first shelling in 2015 when she was 4 years old, now gets scared every time she hears a loud noise and cries: “Bomb! Bomb!” This is what children living along the LoC and the International Border grow up with: they know no other life.

Neha, a young school teacher, who also lives in Arnia tells me how they are scared to go to into the makeshift shelters in community halls and schools whenever the firing starts. “There is no concept of gender segregation there. Same halls, same bathrooms are to be used by men, women, girls and boys. How can we go there, you know the times are not trustworthy.”

Often when firing starts, parents send off their children to other villages away from the border, but they have to stay back to tend to their livestock. “Our land and our animals are the only sources of income for us. We have nothing else. I would any day prefer to save my cows over myself during a firing incident,” said Neha’s mother. Most of the population living along the borders rely on agriculture and on their livestock for their livelihood. Few are temporary employees in the government, while others have small shops.

Saujian in 2016 witnessed heavy shelling. Allegedly, Pakistani forces targeted the market where the Indian forces used to store their oil. The entire area burnt down. The shopkeepers re-constructed the market from scratch with their own money, borrowing from relatives or getting bank loans.

As the LoC is not a permanent border, both countries keep changing the demarcation and, as a result, many people have lost their land to this boundary war. As the LoC is not a permanent border, both countries keep changing the demarcation and, as a result, many people have lost their land to this boundary war. In most places, the LoC is marked with a barbed wire. The villagers’ land is often occupied by border forces without paying any compensation or allocating a different piece of land.[v] “We have sold our animals because there is no land left for grazing,” said a resident of Saujian, Poonch.

Considering such harsh conditions, it is difficult to understand why people are still living there. For most residents, however, their lives are rooted in those villages and their livelihood depends on the land. Many people have been displaced internally and relocated from one border village to another. In the 1965 war, Pakistan’s main target was the Akhnoor sector in Jammu.[vi] Gulabo Ram and his family were relocated from Akhnoor and given land in Treva, R.S Pura, two kilometers away from the International Border. “It took us ten days to walk from Akhnoor to Arnia and yet we were relocated to a place that too witnessed thousands of firing incidents since then,” recalled Gulabo Ram. Last year, in the month of May, there was an unprecedented firing that lasted for four hours.

Apart from the firing and artillery shelling, the residents along the LoC and the International Border also live with the uncertainty of anti-personnel landmines. Most of the landmines placed by the Army are signaled, but occasionally they are planted randomly or may drift from their original position for the rain or a snowfall. Residents, especially children, are very frequently the unintended victims of these mines. In 2017, Khalid, a nine-year-old boy, went to a nearby field to collect wood to fuel the traditional stove in his house. Little did he know that he had picked up a landmine along with the wood. The landmine exploded in the stove when he fired it and Khalid lost the right eye, leg and arm.

“No! Media is not authorized to enter this gate. Please leave your cameras and phones here.”

There are villages along the LoC where no one except residents, doctors and government employees are allowed to enter. Media are among those who are not welcome. I wanted to go to Amroohi in Karnah, which I had already visited in 2018. However, in July 2019, the men at the Army checkpoint asked me to get permission from the Sub District Magistrate (SDM) office and the brigadier stationed in Tangdhar. Despite having managed to get the required permission, the Commanding Officer of that unit refused to let me go through the gate that locked the village. “They don’t want outsiders to know what they have been doing inside the villages. They don’t want the secrets to be leaked out,” said my local guide.

Churranda had a melancholic feel to it; the media has rarely been to this village and when they did, they were handed a list of dos and don’ts by the Army. Similarly, in a village in Uri, Churranda, I had to leave my camera, phone, notebooks and pens behind. Churranda had a melancholic feel to it; the media has rarely been to this village and when they did, they were handed a list of dos and don’ts by the Army. A few years ago, according to the locals, the Army burnt down many houses just to clear the land in order to plant anti-personnel landmines. These families now either live in their neighbors’ and relatives’ houses or have borrowed money to build new small houses.

These villages are enclosed with a gate that is locked from 7 pm till 7 am. In these twelve hours the Army personnel guarding the gate is not available and if there is any medical emergency the local residents are left stranded. In the occurrence of cross border firing, the administration waits for a day and only then, if the firing continues, would evacuate the villages. During such skirmishes, if a villager is injured he would not be able to reach a nearby hospital as all the roads are blocked by the armed forces. Manzoor, a school teacher from Balakote village in Poonch, recalls an incident when a school bus got stuck amidst a sudden cross-border firing and a senior teacher got injured. They could not transport him to the hospital on time, and he succumbed right there.

Life along the borderland is harsh and difficult to understand. A couplet by Pakistani poet Jaun Eliya sums it well: “Jo Guzaarina Jaa sake humse, hum ne vo zindagi guzaari hai.” (This unbearable life, yet I have carried the burden throughout.)

References

[i] Naveed Siddiqui. 31st July 2019 Increased ceasefire violations by Indian troops ‘indicate their frustration’, says DG ISPR. https://www.dawn.com/news/1497272

Abhishek Bhalla, 30th August 2019. Truce broken 222 times by Pakistan in August. https://www.indiatoday.in/mail-today/story/truce-broken-222-times-by-pakistan-in-august-1593266-2019-08-30

[ii] John Galtung, 7th May 2015. Violence, Peace, and Peace Research, http://www.jstor.org/stable/422690

[iii] Till now, normal cellular phone calls do not get through from India-administered Kashmir to Pakistan-administered K, while people from Pakistan can call.

[iv] During that time, people from India-administered Kashmir would cross to the other side for arms training. Tariq Bhat, 2nd March, 2019From Heaven to Hell. https://www.theweek.in/theweek/cover/2019/03/02/from-heaven-to-hell.html

[v] Residents of Balakote village in Poonch are fighting a case in High Court asking for a compensation for their land occupied by the Border Forces.

[vi] Anaz Zakaria, 7th August 2018 Between the Great Divide: A Journey into Pakistan-Administered Kashmir. Harper Collins India.

[i] Scroll, 8th Sep 2015. Kashmir is the ‘unfinished business of Partition’, says Pakistan Army Chief. https://scroll.in/article/754127/kashmir-is-the-unfinished-business-of-partition-says-pakistan-army-chief

[ii] Rani Singh, 12th July 2016. Kashmir: The World’s Most Militarized Zone, Violence After Years of Comparative Calm. https://www.forbes.com/sites/ranisingh/2016/07/12/kashmir-in-the-worlds-most-militarized-zone-violence-after-years-of-comparative-calm/

Nawal Ali is a social activist, an independent researcher and a photographer from Kashmir.

SUPPORT US

We like bringing the stories that don’t get told to you. For that, we need your support. However small, we would appreciate it.